Buildings, But How About Books?

Is the end actually in sight?

Speaking to reporters on April 18, Michael Rebell, a lead attorney for the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, said the case seeking billions more in funding for New York City public schools could be drawing to a close.

The journalists listening might be forgiven for skepticism. The CFE case, as it is commonly known, has involved lawyers, politicians, educators and various wonks for 13 years. It began shortly after Rudolph Giuliani became mayor, as the Board of Education (now the Department of Education) struggled to find a new schools chancellor to replace ousted Joseph Fernandez (four chancellors ago), and when Robert Jackson served on a community school board in Manhattan. (He is now a member of the City Council, and heads the council’s education committee.)

Jackson and Rebell, frustrated by the shortages confronting that school district, launched the lawsuit in 1993. Since then, it has meandered its way through the court system and loomed over city and state budgets and decisions about school funding.

The last several weeks have seen more twists and turns, including the latest legal maneuver by Campaign for Fiscal Equity -- this one designed, it says, to force the city finally to ante up billions for city schools.

VICTORY FOR SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION, BUT...

This action comes in the wake of a substantial victory for school advocates -- a plan to get billions more for school construction in the city. But Governor George Pataki and the state legislature continue to resist providing billions more in operating funds for city schools. That resistance spurred the latest CFE action.

In his February, 2005, ruling in the CFE case, Judge Leland DeGrasse called for the city to receive an additional $5.63 billion in operating funds per year (on top of the existing budget , which is currently about $15 billion) in order to give all of its 1.1 million public school students “a sound, basic education.” He also said the schools would need an additional $9.2 billion for adding and improving facilities over a five-year period.

In late March of 2006, the legislature agreed to a plan that would provide the city with $11.2 billion for school construction over the next five years. But the legislature provided only $400 million in additional aid for operating expenses, prompting the latest CFE appeal.

THE CAPITAL FUNDS

When the year started, the two sides in the school funding dispute appeared as far apart as they had ever been. Pataki’s 2007 budget continued his policy of what his critics would call thumbing his nose at -– or, as his staff would put it, appealing –- the court ruling. He provided no funding for capital projects and boosted aid to New York City schools by $329 million – far short of the billions called for in the ruling.

For years, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, while saying the schools needed infusions of money from Albany, had been loathe to take on Pataki or the legislature. The mayor wanted the governor’s support for the ill-fated West Side stadium, some theorized; others thought he did not want to take on a fellow Republican. And some said Bloomberg preferred negotiating behind the scenes to making contentious public pronouncements.

But Bloomberg’s reticence faded after his re-election in November. In February reports began circulating that the mayor might work for the election defeats of key Republican state senators to punish them for not backing more school aid for New York City.

And then the mayor visited another plague on the recalcitrant politicians. The city has a five-year $13 billion plan (in pdf format) to build and improve school facilities. The city and state were supposed to share the tab. When Pataki did not come up with the state’s portion, Bloomberg announced he would be cutting 21 projects, targeting ones in key legislators’ districts. "We picked the schools where the people in Albany have some power," Bloomberg reportedly said in late February. "They're really not going to get away with this anymore."

Apparently not. Under the complex borrowing arrangement hammered out by the legislature, New York City would get $11.2 billion in school capital funds over the next five years. This would allow the city to restore the 21 threatened projects as part of its overall plan to construct or lease 76 additional school buildings, make repairs to old schools, improve science labs and provide for other renovations.

Although the state legislature and Pataki remain far apart on the overall state budget, the school funds appear safe. Pataki vetoed 202 items totaling about $3 billion in the legislature’s budget for fiscal year 2007, but did not touch the $11.2 billion for school construction or the additional operating money.

GODSEND OR GIMMICK?

School advocates have hailed the additional money for construction and improvements. “We’re very pleased,” said Noreen Connell, executive director of the Educational Priorities Panel. While “in an ideal world the legislature would have complied with the whole court decision,” she said, it makes sense to focus on physical improvements first. “You can’t reduce class size without new classrooms.”

Bloomberg commended the deal as an “excellent agreement” and applauded the “real and impressive leadership from Speaker Silver and Majority Leader Bruno, who rolled up their sleeves, got to work and found a way to deliver for our students."

But the funding plan worries some fiscal experts. The first part of the money – about $1.8 billion – would come from funds the state would borrow from the State Dormitory Authority. The rest -- up to $9.4 billion -- would come from borrowing done by the city through another public authority, the Transitional Finance Authority. The state would guarantee the new bonds and agree to provide enough future funding to sustain the bonding program.

Why such gyrations? The city and state governments themselves cannot borrow the money because of restrictions on government borrowing. Most importantly, the voters would have to approve it – and they might balk. After all, voters rejected a school bond act in 1997. But borrowing through the public authorities -- backdoor borrowing as critics call it -- avoids such pitfalls.

“It’s gimmicky,” Connell said. “But Albany is gimmicky.”

“This points out the need for debt reform,” said Elizabeth Lynam of the Citizens Budget Commission, a watchdog group. While agreeing that the schools need physical improvements, she said, “From the state’s perspective, it’s not a great deal because it’s going to add to the state’s debt, which is already jeopardizing the health of the state.”

THE OPERATING FUNDS

Some education advocates have concerns too. The Campaign for Fiscal Equity, in particular, charges the legislature and governor continue to flout the court’s ruling calling for additional billions to pay teachers and provide supplies. "Our schools need operating monies desperately,” CFE executive director Geri Palast has said, “and we will continue to press the case until the court-mandated operating aid starts to flow and the constitutional violation at the heart of our case is fully corrected."

And so the group has asked the state’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, to force the state to ante up. In its appeal, CFE requests an expedited hearing so the city can begin to see the additional money by the next school year. It wants the court to issue a clear order that the state must begin giving billions more to the schools. If the state still refused to act, the courts could impose sanctions, Rebell said.

The sanctions spring from one of the main frustrations of those fighting for more money for schools. Although the courts have repeatedly ruled in favor of increased funding, the state has dragged its feet, failing to address the issue in its budgets and continuing to file appeals. “The failure of the governor and the legislature to respect a clean mandate of this court...substantially undermines the rules of law and public respect for court orders,” the Campaign for Fiscal Equity said in its appeal letter. Now, the group hopes finally to get the money and, it says, end the case.

But it won’t be that simple. After the campaign announced its appeal, Pataki spokesman Scott Reif told the Albany Times-Union that the state might take legal action of its own. "The state's attorneys are reviewing whether we now need to file a cross-appeal to protect the state taxpayers' rights in light of today's unexpected action by CFE," he said.

The Campaign for Fiscal Equity’s request comes after another court decision -– this one in late March –- did little to clarify matters. The ruling by the Appellate Division, the court that has been most hostile to CFE’s arguments, left much room for interpretation. It said, on the one hand, that New York City schools need at least $4.7 billion a year more in state aid than they now get and another $9.2 billion in capital funds over the next five years. And, the judges said, the 2007 budget should reflect this. But then the court, by a 3-2 vote, went on to say that only the governor and the legislature, not the courts, could determine the exact amount of education aid.

Both sides declared victory. Governor George Pataki hailed the decision for reaffirming “the longstanding constitutional principle of separation of powers.” The Campaign for Fiscal Equity on the other hand, cheered too: “The court brushed aside the governor’s latest appeal, ruling that it is â€undisputed’ that the state has failed to appropriate the amount of funding needed to meet the CFE mandate.”

Calling the decision “poorly drafted mind-blowingly muddled,” E.J. McMahon, director of the Manhattan Institute’s Empire Center for New York State Policy, wrote, “With his gift for ambiguity [Presiding Justice John] Buckley has done his part to ensure that all the lawyers involved in this case will be busy for years to come.”

Given the history of this case -- and the painfully long battles over school funding in other states -- McMahon could well be right.

Â

Behind the Dropout Rate

Slightly more than half of all New York City high school students graduate on-time, according to the Preliminary Mayor's Management Report, the administration’s accounting of its success and failures. Even by the administration’s own counting, this represented a slight decline from the previous year. And a few days later, the State Education Department released its own graduation rate for the city and found it to be far worse -- 43.5 percent.

The difference in the numbers points up the lack of good information about high school completion in New York. The drop out data is not accurate; the definitions are constantly changing. There must be at least three different kinds of students who are considered graduates. In some reports, they count people who receive GEDs as a graduate. In some reports, they don’t count them. In some reports, alternative certificates count. In some they don’t. On and on and on. It’s very confusing.

The failure of so many students to earn a real diploma is a major issue in the state and the city, as well as across the county. And when we don’t see exactly what is going on, broken down by race, by ethnicity, by disabilities, by socioeconomic status, we don’t have the basis to judge whether what we are trying to do is effective. You need an accurate understanding of what the problems are before you can design appropriate solutions.

The graduation rate crisis is not unique to New York or to New York City. But with regard to Latino and black students, New York is probably the worse state in the nation in terms of who is enrolled in ninth grade and who earns a real diploma on time four years later.

According to estimates of the national graduation rate data crunched by the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., there’s a 50-50 prospect of graduating on time if you are black, Latino or native American. When you disaggregate this further by gender, you find that black, Latino and Native American males have less than a 50 percent likelihood of earning a real diploma. And by real diplomas, I don’t mean GEDs, and I don’t mean alternative certificates. We’re talking about a real diploma. That’s what you need to get into a college or have a meaningful career of gainful employment

WHO COUNTS AS A DROPOUT

There has been a state requirement that a student has to have been in high school for two years to count as a graduate or a dropout. So all the kids who drop out in ninth grade or tenth grade have been removed from the whole calculation. Now they are going to change this so students have to be in high school for only five months to be counted. But still all of the students who come into ninth grade and drop out right away are removed from the calculation. Basically, they disappear. The effect of that is to make the graduation rate look a lot higher than it really is.

Any student who is in the juvenile justice system is not counted as part of New York graduation rate. These are the students we should be most concerned about, but we don’t know what is happening to them.

WHO COUNTS AS A GRADUATE

In the reports on New York City, students who receive a GED are counted as graduates. The benefit of earning a GED, according to national research, is just a slight improvement over dropping out. On the other hand, there is a tremendous difference between earning a GED and earning a bona fide high school diploma.

Federal law requires that in calculating graduates for the purposes of No Child Left Behind, you look at students who graduate from secondary school with regular diplomas. The federal requirement does not count GED students, and the graduation rate is the percentage of students measured from the beginning of high school. Not counting them if they haven’t been there two years is just something that the State of New York has made up.

THE RACIAL DIVIDE

A study done by Robert Balfanz of Johns Hopkins looked at school district data and state data and found that approximately 84 percent of minority students in major cities in New York attended what he called “drop out factories.” A drop out factory is where less than 60 percent of ninth graders are still enrolled in 12th grade – regardless of whether they get a diploma. If all of the ninth graders showed up in 12th grade, the schools would fall under their weight. That’s how bad a situation we have.

In real numbers –- I took this off the state web site -- there are 46,298 students enrolled in grade 12 this year. That’s only 49 percent of the 93,775 ninth graders who were enrolled in 2002-03. And this is actually a 10 percent improvement from previous years.

When you disaggregate race and gender for the class of 2001 in the State of New York 28.6 percent of Latino male and just under 30 percent of black males who started ninth grade graduate with a real diploma four years later. The goal in the state of New York is 55 percent. That’s the goal. They’re shooting for a 55 percent graduation rate. It’s just outrageous.

New York City is not the worst city in the state. In Syracuse, just over a quarter of all students who start ninth grade graduate with a diploma on time.

But in New York City for the class of 2001, 32 percent of blacks and just over 30 percent of Latino students graduate with a diploma on time. The city’s official report gives an inflated rate. It states that for blacks and Hispanics, the rates are around 41 percent in terms of who graduates on time. And, it says, if you go five, years, six years seven years out, these rates improve. But the city does not tell you that probably most of those are not real diplomas, certainly not Regents diplomas.

This misinformation is devastating. How can we know if we are doing better if we do not get an accurate reading of where the problems lie? It also affects where resources are allocated. We are not going to spend enough if our focus on the problem isn’t sharp, and we can’t see what’s really going on.

ASSESSING ALTERNATIVE PROGRAMS

This also concerns one of the solutions you hear a lot about -- alternative schools. Some of the alternative schools are fantastic, filled with dedicated educators who do wonderful things for kids who are at risk and need these programs. But there also are alternative schools where kids are being warehoused, where they are being enrolled in GED programs, where we don’t know if they’re staying in school or dropping out. These students are not getting the kind of education they need to get a real diploma.

In designing and investing in alternative programs it is important to have data so we can know who is going and can then evaluate whether these programs are effective or not. If they are warehousing kids and simply making the graduation rates look better, everyone can pat themselves on the back while the kids wind up in prison.

SPECIAL ED STUDENTS

For kids with disabilities, the situation is even worse. According to a report issued by Advocates for Children in June 2005 called “Leaving Schools Empty-handed,” only 11.84 percent of students who receive special education leave school with a Regents or local diploma. Only four percent of the kids with emotional disturbance— where blacks student are disproportionately represented – wind up with a real diploma. Less than 1 percent of students in special education who end up in one of the GED programs actually earn a GED. There are so-called IEP (for individual education plan) diplomas drawn up specifically for special education students. Nobody feels a special education diploma is even roughly equivalent to a Regents diploma. But students who receive them are reported as having graduated.

When we try to evaluate our policies, we weigh whether or not we need more prisons, more money invested in juvenile justice and more police in our high schools or whether we need to train teachers better and invest in a higher quality of special education and in proven effective alternative schools. If, as policy makers, we don’t have accurate data, we are not going to be able to make those decisions. And eventually the public will pay the cost through increased crime and welfare costs and a lack of tax dollars from income that doesn’t get generated because there is no gainful employment for people who get a GED.

Daniel J. Losen is senior education law and policy associate with the Civil Rights Project at Harvard Law School.

In Defense Of Big Schools

Seward Park High School

Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club met with author Samuel Freedman, New York Times education columnist, and Jessica Siegel, the teacher who is one of the subjectsof “Small Victories: The Real World of a Teacher, Her Students and Their High School."An edited transcript is below:

Gotham Gazette: “Small Victories” is about a high school on the lower East Side during the 1987-88 school year. Mr. Freedman, this book was written almost 20 years ago. Is it a picture of a certain time in New York City history, or do students still face these same issues in 2006.

Samuel Freedman: It is close to 20 years, but I think that a lot of the issues remain very familiar in the sense that you’re still dealing with a public school system that doesn’t have enough resources, that doesn’t have enough modern enough facilities, that’s contending with a very economically poor student body, that’s contending with the biggest wave of immigration coming into the city in more than a century.

Some aspects have changed. At the time I was writing this book, the school system was divided between grades kindergarten through 8 -- which were decentralized and overseen by elected community boards, which tended to be real sinkholes of corruption -- and then the high schools, which were centralized and actually, I felt, run pretty effectively through borough offices and then, ultimately, the Board of Ed.

Another thing that’s different is that, much to my chagrin, schools, like Seward, have become a ready symbol, and I think, not a correct one, under the current leadership of the Department of Ed, for everything that’s seen as ailing in secondary ed. That’s a perception I don’t particularly share.

The superhuman efforts by a number of the teachers and the tremendous will on the part of many of the students to get to college, to have fruitful lives, to really become citizens in every sense of the word -- that’s unchanged and that’s still the very best part of what goes on in New York City public schools. It’s sort of the everyday miracle.

Gotham Gazette: Ms. Siegel, the school you teach at now, Abraham Lincoln High School, in some ways seems similar to Seward Park. It’s a large high school, and there are 30 different languages spoken there, according to Inside Schools. How is the experience you’re having now similar to the one you had in 1987-’88, and how is it different?

Jessica Siegel: Well, the stuff you just talked about is very similar. A lot of immigrants. In the case of Abraham Lincoln, Russians, East Indians, Latinos, and then, of course, native-born African Americans who are an important part of the school. And at Seward Park, it was predominantly Latino, Chinese, Asian, some whites, believe it or not, and African American.

"With all that school had going for it, there should have been a way to keep it open rather than to break it apart."

What’s changed is the school system, and the centralization of the school system, where schools like Abraham Lincoln and Seward Park are now targets for reorganization and are seen, as Sam said, as failures. So there’s this centralized sense about curriculum. Abraham Lincoln has been on the impact list, which means that the amount of incidents in the school is too high, so they’re constantly being monitored by the superintendent.

It’s really under the microscope. And so people are running scared. Teachers are running scared because the pressure is on from the top down to the teachers in a way that I think has a negative aspect on teaching and learning.

Gotham Gazette: One of the things that struck me about your teaching experience at Seward Park was the journalism class. It seemed like you had a lot of freedom to work with individual students. Would having a class like that be more difficult in this system?

Jessica Siegel: Well, I’m teaching journalism this term. I started a journalism class. One of the reasons that I went to Abraham Lincoln was I liked the principal, and he wanted to get a journalism class up and running.

Interestingly enough Abraham Lincoln – like Seward Park – has alumni who feel really strongly about this school. For some of the older alumni, the school newspaper had a really big effect on them, and supposedly they wanted the newspaper up and running. So I'm in the process of trying to get the first issue out. It's a way to have kids write about what they care about.

The problem is, going back to the point that Sam made about big schools versus small schools is that a lot of classes like journalism electives are eliminated in small schools. Some of the classes that manage to pull kids in – music class or art class – are eliminated. It's one of the unintended consequences of this big push for small schools that a lot of the classes that turn kids on to school are eliminated.

The Push for Small Schools

Gotham Gazette: Do either of you see an advantage to small schools? Is it a tradeoff or just a misguided policy?

Samuel Freedman: I think it is a tradeoff, and I'm not a doctrinaire foe of small schools by any means. One of the best arguments in their favor is that in larger schools there is a greater chance kids are going to get lost in the massiveness of 2,500 to 4,000 students. They are much less likely to get lost in a school of 300 or 400.

I am really concerned, though, in a couple of ways. This was something that started under former Schools Chancellor Joe Fernandez – it predates Joel Klein by a decade or more. There was an earlier generation of small schools that were created with a lot more deliberation, they were opened a lot more gradually, they had a much more thought-through pedagogical center or core academic area. It's not surprising that they have been successful.

The problem is that you have this tail of this big grant from the Gates Foundation wagging this policy dog at the Department of Ed. Because Gates has a big priority to start small schools, the Department of Education is jumpstarting 50 a year, year after year. It's just impossible to have quality opening up schools in that kind of frenetic way. It also means a lot of these schools get opened up with these ultra-niche academic orientations – sports careers or architecture – that I think are really preposterous for a ninth grader. I think what they tend to do is serve the interests of community organizations that are sponsors. These may be perfectly well-intended sponsoring groups, but that doesn't mean that the high school as a whole is going to work with a curriculum that is defined that narrowly, especially when there is a good reason to put more emphasis on language, science, math and a lot of the core subjects.

Two more points: One, it has created an even more Manichean system of who gets the best students and who gets the rest of the students. I saw that already when I wrote the book about Seward. Seward's incoming freshman, 10 percent of them were reading at grade level. Amazingly Seward graduated 30 percent reading at grade level, which I saw as a huge accomplishment. Now that there are extra layers of skimming going on, by the time kids get into the old-fashioned zoned high schools there is a sense that this is the school of last resort – anyone with any real prospects has gotten in somewhere else. Plus as schools get shut down to be broken down into smaller schools – Martin Luther King in Manhattan is a good example -- the unwanted kids get shunted into other zoned high schools. The detritus of King gets sent to Washington Irving or Norman Thomas and overcrowds those schools, destabilizes those schools, and creates a self-fulfilling prophecy in which schools that were functioning at a satisfactory level if not an exalted one suddenly are struggling not to have fights every day.

Two more points: One, it has created an even more Manichean system of who gets the best students and who gets the rest of the students. I saw that already when I wrote the book about Seward. Seward's incoming freshman, 10 percent of them were reading at grade level. Amazingly Seward graduated 30 percent reading at grade level, which I saw as a huge accomplishment. Now that there are extra layers of skimming going on, by the time kids get into the old-fashioned zoned high schools there is a sense that this is the school of last resort – anyone with any real prospects has gotten in somewhere else. Plus as schools get shut down to be broken down into smaller schools – Martin Luther King in Manhattan is a good example -- the unwanted kids get shunted into other zoned high schools. The detritus of King gets sent to Washington Irving or Norman Thomas and overcrowds those schools, destabilizes those schools, and creates a self-fulfilling prophecy in which schools that were functioning at a satisfactory level if not an exalted one suddenly are struggling not to have fights every day.

The last thing is that the critical mass of large schools allows for sports teams, school newspapers, musical groups, debate clubs, all kinds of extra-curricular activities. While it is true, large schools can't give the individual attention small school can in terms of guidance counselors or classes, having a school newspaper is a way of giving individual attention that small schools cannot offer.

Jessica Siegel: Let me jump off on that. A lot of the big schools in Brooklyn have become extremely overcrowded. The kids who don't get into these small schools end up in these large schools, and the hallways become extremely crowded. If there aren't difficulties in the school already this helps to create them.

I feel strongly about the intimacy small schools can give. But the key is small class sizes. With the exception of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, few people are talking about small class sizes, which could be in a small school or a large school. I don't want to be idealistic, but if you have a class of 20 you can do anything. Great teachers can be greater, and even mediocre teachers can be a lot better, because you have fewer students. Speaking as an English teacher, you'd have fewer papers to mark, so you can give more essays or other kinds of writing than if you have 34 kids in a class. It's obvious, but nobody is talking about it. The whole discussion is small schools, small schools, small schools, but it's small class sizes.

I also think that if they had really thought through these small schools, they could have the extra curricular activities – journalism, band, chorus – in the building that houses four or five schools. Seward Park is now five schools. Why not have them join together in putting together a school newspaper or having a band? It's about this competition for getting better students rather than working together and having those kinds of activities.

Does Integration Matter?

Gotham Gazette: Jonathan Kozol recently wrote an article for Gotham Gazette Segregated Schools: Shame Of The City, in which he argued that one issue that is being ignored is racial segregation. He said that until that is confronted, other reforms will not accomplish much. What is your perspective on that?

Jessica Siegel: What is the percentage of the public schools students that are children or color? Eighty-five percent? It's not even relevant. That's who is in the public schools. To me it's not an issue of segregation so much as what kind of education you are going to give to the kids there.

Samuel Freedman: I completely agree with Jessica. Kozol espouses a point of view you pick up in education schools. But it is a high-minded excuse for paralysis. It would be great to rewind the clock back to 1973 when the case out of metropolitan Detroit was decided and the Supreme Court decided there could not be regional remedies [to school segregation]. When that ruling came down, it was basically the end of what Kozol would wish for. Would it have been better if that ruling went the other way? Yes, but that was 32 years ago. It's part of educational suicide to say now, however well intentioned you are, that until you solve poverty or segregation nothing can happen in the schools. Something has to be able to happen in the schools.

One of the things I saw at Seward was that demographically and economically, you would say nothing should have happened there. But amazing things actually did happen there. Would it have been better if half of that school were kids of upper middle class parents from the East Village? Probably, but in the meantime you had to teach and make things happen for the kids who are there. So by saying nothing can ever change until poverty and racism are solved is like saying you can never have any effect -- which is the worst message.

The No Child Left Behind law requires disaggregation of data by race. No matter what No Child Left Behind's faults are -- and there are many -- this has been an important way to bring the equity issue to bear.

There is a real feeling in a lot of the minority community that, whether or not integration ever would have been the remedy, it's not the remedy now. Something has got to happen for our children right now. I know someone like Kozol sees himself as speaking on behalf of these families and students, but I think right now he speaks against their interests in a way.

The Closing of Seward Park

Gotham Gazette: Can you speak a little bit about what has happened in Seward Park since the book? Both of you alluded to the fact that it has been broken up into small schools.

Samuel Freedman: I think it’s criminal that a school like Seward should have to be closed, and I think it’s an indictment of the Department of Education and its policies. With all that school had going for it, there should have been a way to keep it open rather than to break it apart. It should never have come to this.

Seward had a great faculty when I was doing the book, and a lot of those people are still teaching at various schools, a superb faculty. But it also had a really, really phenomenal principal, a guy name Noel Kriftcher and I think if I had to point to one thing, aside from this misguided Department of Education policy, that damaged Seward and made it vulnerable to this policy is that there was a definite decline in the quality of the principals over the years at Seward. Noel Kriftcher was a uniquely talented guy who was bright, experienced and savvy dealing with the board and had high standards. He also was a physical presence and an athlete, someone who could do well in an urban school and keep order without metal detectors. The guy who replaced him, who was his protégé, was a capable guy who also kept the school in pretty decent shape and then I think it tailed off.

What this points to is that even with a really good faculty and even in some ways some very good student demographics you need to have a great principal, and you need to cultivate people like that.

One of the other problems the Department of Education has had is that they have not adequately nurtured the talent within the system to create and bring along the next generation of great principals. They took a real bold and I think mistaken step -- again with a lot of private philanthropic money – to create a principals academy aimed at taking people either from other cities with some educational experience or taking people with no educational experience and thinking that you could in short order turn them into quality New York City principals. And that was folly. In the course of doing that program, they jettisoned, out of their arrogance, an existing program for a fraction of the money that used experienced New York City principals to mentor young future principals and assistant principals and that had been really successful.

Where Are They Now?

Gotham Gazette: Are you still in contact with the people in the book.

Jessica Siegel: Oh yeah. Noel Kriftcher I see every so often. He's now at Polytechnic University doing collaborative work with high schools.

The thing about this book that is truly remarkable -- and I can talk about it almost as if I'm not a character in it -- is that there are very few books in which minority teenagers come across as complicated individuals. They seem equal to me... It's not written as this missionary coming in, this wonderful, perfect person. It's very much about me, one teacher, and other teachers, and the students as equals, in terms being of interesting, complex individuals.

Angel Fuster was one of my students. I am in touch with him – in fact I spoke with him about two days ago. He is a lawyer. Carlos Pimentel also is a lawyer.

Denise Simone, who was another one of the teachers there, is in one of those principal institutes. She is going to be a principal. She has been teaching for 25 years, and is one of the few people who has been an experienced teacher; she is with people who have been teaching for two years or four years.

Bruce Baskind, another colleague of mine, is a social studies teacher at Brooklyn Tech.

Steve Anderson was at Seward Park until its very end and is now going to help design one of those small schools.

A Teacher’s Trials

Gotham Gazette: Throughout the book, there is a tension between you loving teaching and you wanting to leave. At the end of the book -– and I'm sorry if anyone hasn’t gotten to the end –- you do leave. But then you come back to the New York City school system. Can you talk a bit about why you wanted to stay so much and why you wanted to leave.

Jessica Siegel: Well, it's a hard job. In high school, you teach five classes a day, and if you have 35 kids in a class, and I'm going back to that issue of class size, and you're an English teacher and you feel strongly about writing, you're always assigning papers. So it's hard.

But it's also one of the most rewarding careers you can possibly have. You know you're doing something worthwhile. And at least with adolescents, there is this interesting combination of maturity and immaturity. You get immediate feedback about how you're doing. That can be both good and bad, but ultimately it’s rewarding.

"If you have a class of 20 you can do anything. Great teachers can be greater, and even mediocre teachers can be a lot better."

At Brooklyn College I've taught a lot of the teaching fellows. My feeling about that program is that it's throwing people in with very little preparation. While some of the people are staying -– and there are some very remarkable people -– I wonder what the dropout rate is after two years. Probably a different version of the Teacher Corps –- a program started in the 1960s where people came in for a year and got to know the community and slowly came into [teaching] -– might work better than throwing people in with only a summer's worth of preparation. Because it's very difficult.

There needs to be more thought about how you can both bring people in and get them to stay. Not making them sign on the dotted line that they have to stay for five years, but what can you do to make it easier for people to adapt. Another thing in the high school might be having them teach only three or four classes for a couple of years while they get acclimated.

Joan DeCamp: A lot of people would like to go into teaching but when I look at it the experience is so unsupportive compared to any other job. If you go to a company or a business, they don’t just sit you down at a desk and say, “OK, here’s your job. We’ll see you at the end of the year and see if you got it done.”

It seems teachers are not supported. It’s not a team environment, or a collegial environment because you have to be in the class all the time with students. I don’t get the sense that it’s your own classroom, your own privacy, your own place. There’s no phone access. There’s not a whole lot of things that most professionals have and would want to have. And I think that keeps a lot of people from going into it.

Samuel Freedman: The kinds of things you talked about –- not having your own room, not having access to a phone -– these are some things that push really good teachers out of New York to either private schools or to suburban schools. And it goes right to issues of money. The Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit supposedly got settled, and that money still has not been dispersed. And when it comes through the question will be how will it be spent. It seems to me you articulated some of these poignantly basic, fundamental things that would help teachers feel a higher regard and more comfortable continuing on the job.

Helping Students with Problems

Kate Stoehr: I work in the foster care system, and I’m thinking about behaviors and mental health issues, stuff that is going on at home and how that bleeds into the classroom. I don’t know how you would even begin to teach a classroom of 35 kids of whom 30 or whatever might have extraordinarily high mental health needs and really messy family situations. I only know about it from the foster care perspective. What from a teacher’s perspective can we do?

Jessica Siegel: Well, like I said, smaller class sizes. Obviously they need to have social workers and guidance counselors and make guidance counselors put more emphasis on counseling as opposed to just helping the kids with their programs. Bringing in community based organizations so there’s the connection to the community, all those kinds of things.

But I think again it’s really about making it so that teachers are working with a smaller number of students. The whole point is getting to know your students well. If you have 35 times 5 – 175 kids – how can you really get to know all of them well? Strangely enough you may get to know the kids who give you the most difficulty but all these other kids get lost in the shuffle.

Samuel Freedman: One really interesting program which I’ve written about is a pilot program out in Oakland, California, that put mental health clinics into high schools, with foundation funding. The idea was to address exactly what you’re talking about, Kate. In Oakland, there was a tremendous problem with gang violence and drive-by shootings, really post-traumatic stress disorder, if you had to put a name on it, for kids in their teens who had experienced or witnessed horrific violence. They tried to bring the mental health service right there. Ideally you do that in many other places.

It’s a shame we tend to think of school health clinics only to dispense the TB test and the flu shot or, in a more volatile setting, condoms issue, when they could do a lot of mental health work as well.

But I want to say a few things I saw at Seward Park that were important, short of being able to bring in that kind of mental health service. I was always struck that Jessica and the other teachers, even with the huge numbers of students in the school, shared so much information with one another. When teachers had lunch with one another, when they sat in the English or the history office together, the friendships they had with the guidance counselors, with truant officers, with the coaches, with the principal, was really a kind of informal loop of information. It was good for the teachers because they felt less isolated but it was also a sharing of information.

But I want to say a few things I saw at Seward Park that were important, short of being able to bring in that kind of mental health service. I was always struck that Jessica and the other teachers, even with the huge numbers of students in the school, shared so much information with one another. When teachers had lunch with one another, when they sat in the English or the history office together, the friendships they had with the guidance counselors, with truant officers, with the coaches, with the principal, was really a kind of informal loop of information. It was good for the teachers because they felt less isolated but it was also a sharing of information.

The other thing, and it’s part of what’s magical about education and part of why I’ve never tired of writing about it, is that good teaching or great teaching gives kids a way to express and deal with traumas. There are layers and layers and layers of domestic disturbance and violence and God knows what else. The kids I knew at Seward: One kid whose parents had moved back to the Dominican Republic, 17 years old, living on his own. Another girl who moved out from an abusive home and was in a shelter basically. Kids who had to work jobs, parents who were well-meaning but didn’t know English or who were working multiple jobs and were never around. Violence. Kids running gauntlets of drug dealers on the way to school.

One thing Jessica did that was very successful for teaching but also for these kids’ mental health was to make a lot of use out of writing autobiographically. It was not the only writing they did, but it gave them a place to put those feelings and try to make sense of it and also let Jessica know what the kids were dealing with and find a way to respond.

That was one level, and the school newspaper was another. In the book, I write about a boy who was gay, and I don’t know if he was out or not, but having him write about the experience of gay teenagers was a way of trying to make sense of his own experience. The school newspaper allowed that. There was also a very good creative writing teacher, who did a lot of autobiographical fiction and poetry with the kids.

And then finally there’s something about works of great literature that allowed kids to make the imaginative leap from their experience on the Lower East Side in 1987 to other places. I’ll never forget Jessica teaching “The Great Gatsby” to this class of new immigrants. Because of that book, and her ability and their brains, these kids were able to make the connection between their aspirations, their desire to reinvent themselves, to pretend to be things they weren’t and pass over into elite white society to Gatsby. And they were also able to see through that book what terrible things can be lost in the process.

That’s a book that certain people would say shouldn’t be taught in an overwhelmingly minority school. It’s a dead white European male book. And yet it isn’t. It’s a book about human nature and the kids saw themselves in it, and that was another way to make sense of it.

One of the first things Jessica said to me was how amazed she was at what her kids could deal with and still function, still go to school and do work and get to college. Some of what was valuable was that school was kind of a refuge for them, school was the most unchaotic place.

One of my students at Columbia Journalism School is finishing a book about an inner city Catholic high school – Rice High School in Harlem – and the title of the book is “The Street Stops Here,” which was a motto of the late principal there, Orlando Gober. It was an idea not just of crime, but a more general sense of chaos and confusion and family tragedy. School was the safe place, the one orderly part of their lives, and that allowed them to do amazing things.

The Joel Klein Regime

Gotham Gazette: You both talked about small schools, and it seems to some people looking at what's going on in education in the city that the mayor and the chancellor are not doing anything to change high schools beyond breaking them up. Is that a fair perception? What else would you would like to see them do to bring down the dropout rate down and make kids more connected with high schools?

Jessica Siegel: I think there are a number of different systems now. They aren’t looking so closely at the newer schools but they are putting a lot of pressure on the big schools. I’m not necessarily against centralization or mayoral control but I think the chancellor has come in with an attitude that “I’m going to clean up the schools” and there hasn’t been enough credence given to the professionals who are working there. I’ve run into any number of people that have left -- people with as much experience as me or more -- who have felt that they haven’t been respected and that the chancellor and the people that he’s hired have the assumption that “we know the answers.”

There’s hasn’t been enough of let’s stop and see what’s going right and what can we build on. Education journalists like Sam have talked about all the MBAs that have been hired by the chancellor with the assumption that somebody who knows about education will be part of the system and they can’t be trusted. I think that’s a bad attitude. I think that education is a very complex field that involves human beings, it involves a multiplicity of experiences and issues

There’s a tremendous amount of expertise that just hasn’t been utilized. Instead there’s been bulldozing over: “We have the right answer, just follow what we say,” and that kind of thing. It’s disturbing and it’s not respectful of teachers as a profession.

Samuel Freedman: There was a view by Klein and his regime at the Department of Education that everything that preceded them was no good because it preceded them. I don’t think the people have ill intent. It’s bad policy and damaging moves by people who mean to do well but don’t know better.

One of the reasons they don’t know better is they have made a point not to tap the incredible expertise and talent that was in the New York school system before they got here. New York City is the envy of every other big city school system in the country. It’s the envy for its academic result, it’s the envy for the percentage of the middle and upper middle class of all races it’s kept in the system, it’s the envy for the quality of teachers and administrators it has, a lot of which has to do with the historical commitment to public education, in this city. You have to know how to root out some of the terrible parts, like the community school boards, but also look for the brilliant people who are in the system and keep them. And by all means don’t drive them into early retirement, which is exactly what’s been happening. So much expertise, so much wisdom has been lost.

Also in this desire to reinvent the wheels and to pretend that no good programs were here, they lost the chance to continue or to replicate things that did work. I mentioned before that program for mentoring the next generation of principals that was so cost effective -- $3 million to run that a year versus $25 million to run the Leadership Academy.

When Rudy Crew was the chancellor, and also Harold Levy, they had this so-called Chancellor’s District, which were certain chronically ill-performing schools that would be under the direct oversight of the chancellor and that also tended to get a more phonics based English curriculum, language art curriculum in the lower grades, which was successful. Tossed out. Not continued.

"New York City is the envy of every other big city school system in the country."

Another example: When Rudy Crew went to Miami, he created with the teachers union there a program that could just as easily have been done here. Joel Klein talks about wanting to provide incentives, better pay, for teachers in the most hard to fill subject areas and then the lowest performing schools, and I think that is a great idea. What Rudy Crew has been doing in Miami -- and it’s also been done in Denver and a couple of other places -- is to agree with the union on a plan that says that a proven effective teacher, who will willingly go into a low performing school and work a longer school day will get more money. It won’t violate the union contract because that greater pay is pegged to the longer hours. That’s a way to keep harmonious relations with the union, to tap your most experienced people, to reward them – to incentivize, which is one of their buzzwords at the Tweed Courthouse – and they don’t do it.

I think there’s a sense that if they don’t come up with it themselves, it can’t have value.

Â

Keeping New Teachers From Dropping Out

New teachers sink or swim. This is how educators have long characterized entry into the profession. But today the odds of sinking have increased exponentially. In New York City, 40 percent of teachers leave after three years, and 48 percent will be gone after five years, according to the United Federation of Teachers. (Nationally, the figures are 30 percent and 50 percent respectively.)

How did we get ourselves into this situation and how do we get out of it?

A TOUGH JOB

Teaching has never been the cushy job imagined by the public, which mistakenly believes that a teacher’s day ends when school lets out. People outside the field often do not seem to understand that teachers spend hours of additional time making lesson plans, reviewing homework, grading tests.

The profession also suffers from a lack of respect. Parents do not encourage their children to become teachers, and college graduates from our premier institutions view teaching as something to do for a couple of years after graduation before switching into more laudable and lucrative fields.

With increasing pressure on the educational system to meet the demands of a shifting labor market, more and more curriculum mandates and high-stakes testing make it difficult for teachers to be creative in the classroom.

But this already tough job is made worse for beginning teachers, who are typically given the most difficult assignments in the roughest schools. The most vulnerable teachers are handed what no one else wants. For example, the Teaching Fellows program was launched by the city’s Department of Education to staff the city’s lowest performing schools, those that the state classifies as Schools Under Registration Review. The department does this even though the fellows are the least likely of newly hired teachers to be graduates of schools of education.

Conditions for teachers may not have been better in the past, but times have changed. There are expanding opportunities for women who a generation ago saw teaching or nursing as their only career paths.

All of this helps explain why there is a shortage of teachers willing to work in our city's classrooms, though there is no shortage of teachers nationally (except in math, science and special education). The Department of Education has been forced to launch an extensive recruitment campaign, and has relaxed the requirements for these new recruits. This is why, of the 8,000 new teachers who enter the city's schools each year, about 2,500 come in with absolutely no teaching experience, not even as student-teachers.

WHY EXPERIENCE MATTERS

How can we expect people with minimal preparation to be successful in a profession that requires the skills of “parent surrogate, nurse, police officer, detective, psychologist, mediator, bathroom monitor, toilet paper dispenser, janitor, room decorator, quartermaster for school supplies, manager, organizer, lesson planner, cheerleader, lunchroom monitor, negotiator,” as one experienced teacher has put it.

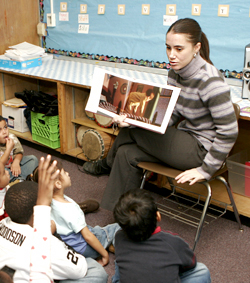

Teaching is all about relationships — the building of relationships between teacher and students. That’s why it is so hard. One elementary school teacher must have relationships with up to 35 very different individuals, each with diverse learning styles, needs, and levels of engagement. A high school teacher will typically teach 150 students.

There is research on the extraordinary number of decisions that a teacher has to make at any given moment —- more decisions minute-by-minute than a brain surgeon. The most conservative estimate from this data has teachers making approximately 130 decisions per hour during a six-hour school day, and this reflects only those decisions made within the classroom. This is extraordinarily daunting and often intimidating for new teachers. It makes support from administrators and colleagues so vital.

HOW TO KEEP NEW TEACHERS

Teachers Helping Teachers

According to a recent MetLife Survey of The American Teacher, the role of supportive relationships is the most important factor in helping a new teacher become a successful teacher. Today’s corporate world may emphasize teamwork, but many teachers remain in isolation in their classrooms.

According to a recent MetLife Survey of The American Teacher, the role of supportive relationships is the most important factor in helping a new teacher become a successful teacher. Today’s corporate world may emphasize teamwork, but many teachers remain in isolation in their classrooms.

Teachers Network, the non-profit organization where I work, has published numerous studies of the impact of teacher collaboration. For example, Sarah Picard, a teacher new to second grade, documented how her collaboration with an experienced teacher led to success in her Lower Eastside classroom. What began as informal sessions between the two of them to talk about children’s progress turned into regularly scheduled weekly meetings to investigate individual students’ reading abilities. These sessions became the two teachers’ main tool for understanding children’s progress and helped them choose strategies to support their students’ learning. The collaboration continued throughout the year and, by June, 93 percent of Picard’s previously-struggling students were reading on grade level.

At Manhattan Comprehensive Night and Day High School, Penny Arnold created a study group for colleagues who, like her, supervised student teachers. The teachers reported that, as a result of these conversations, they were better prepared to help their student teachers. The high school classes in turn benefited by exposure to new ideas, more attention, and better planning.

A variety of methods foster teacher collaboration and so can help change the nature of schooling. Team teaching, team planning, and such programs as the Bronx teacher leadership program in which teachers share classroom assignments so they can also take on leadership roles in the schools, will radically change our model of schooling. Teachers will no longer be on their own behind closed doors.

Teachers as Leaders

Teachers themselves can assume leadership roles, mentoring new teachers, designing and facilitating professional development for colleagues, serving as grade leaders and department chairs, and becoming members of school leadership teams.

Just as young, bright people in the business world succeed with proper mentoring, new teachers require mentors —- not buddies, but veteran teachers who have been carefully selected and fully trained. Building this relationship takes time; teachers say they need a minimum of five years to feel competent and confident in their classrooms. So, a one-year program would be insufficient.

The Role of the Principal

Effective leadership in schools is also critical. The best principals are veteran teachers who can present model lessons, coach teachers and lead informed discussions on teaching and learning. They remain connected to the classroom and can relate to their teachers and the students. Good principals create structures for teachers to work as a community. They provide resources — time, funding, space, and support — for collaboration, and they treat teachers as professionals.

Effective leadership in schools is also critical. The best principals are veteran teachers who can present model lessons, coach teachers and lead informed discussions on teaching and learning. They remain connected to the classroom and can relate to their teachers and the students. Good principals create structures for teachers to work as a community. They provide resources — time, funding, space, and support — for collaboration, and they treat teachers as professionals.

This differs from the traditional principal who too often ruled autocratically. It also differs from the current trend of quickly moving fledgling teachers into administrative positions. Can such relatively inexperienced principals serve as instructional leaders? Deputy Chancellor Carmen Fariña often cites her 22 years as a classroom teacher as the number one reason for her success as a principal, a superintendent and currently as the city’s educator-in-chief.

Lessening Load, Increasing Pay, Fixing School Buildings

Schools have to reduce the teaching load for new teachers and stop giving them the assignments that no senior teacher wants. New teachers need to observe other more experienced teachers, but this is impossible with a full teaching load. Changing this and lessening demand on new teachers will require incentives for senior teachers to take on the tough assignments. The teachers union has advocated pay differentials for experienced teachers willing to work in hard-to-staff schools.

Ultimately, schools alone cannot do all it will take to attract and keep new teachers in the profession. We need to ensure that teachers have decent working conditions. Too many schools need renovation, are overcrowded, and are sorely in need of modernization, including up-to-date science laboratories and technologies. Teachers need to be paid enough so they can afford to live in the city where they teach. And -- here is a “no cost” item -— we have to start respecting teachers, turning what has become a thankless job into an honored profession.

Ellen Meyers is senior vice president of Teachers Network, a national nonprofit organization that supports teachers to improve student learning.Â

Keeping Kids in School

Najsha Chacon felt discouraged by her class work at crowded Fort Hamilton High School in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. She began missing more and more of her classes, until there seemed to be little chance she could graduate. So she dropped out.

It was all the fighting and chaos in her school, Alexandria Stewart says, that drove her to drop out of Curtis High School in Staten Island.

Cooper Small had a 97.4 grade point average at low-crime, elite Stuyvesant High School in lower Manhattan. But he thought he was wasting his time.

Every year, thousands of young New Yorkers like these leave high school without getting a diploma. In a society with few good blue-collar jobs and increasing demand for technical skills, the low graduation rate has many people alarmed. It is “perhaps the most urgent problem that the school system faces," according to Michele Cahill, a top Department of Education official, testifying before the City Council.

|

Related Articles - Helping Immigrant Teens Stay in School(Gregorio Luperon High School in Washington Heights) |

STILL AN ISSUE

Last year, the low graduation rate, especially for African-American and Latino students, emerged as a major issue during the mayoral campaign. Democratic candidate Fernando Ferrer made the dropout rate one of his central themes, in part as a way to puncture Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s boasts about improvements in education. Ferrer charged that only 38 percent of city students graduate on time. The debate quickly deteriorated into a squabble over numbers, with the Bloomberg camp saying the on-time graduation rate was actually 54.3 percent.

It was not just the Ferrer campaign that sees the Bloomberg administration's figure as greatly inflated, because, for example, it excludes some special education students, who graduate at a far lower rate, and it includes young people who get equivalency certificates (GEDs).

In any case, with the election over, there is general agreement that the number of drop-outs -- whatever it is -- is too high. Both Mayor Bloomberg and President George W. Bush, after focusing their respective efforts during their first terms on the education of younger students, have gone on record with their concern for teenagers.

Bloomberg announced a series of privately funded initiatives aimed at high schools, including the opening of more schools for students who had either dropped out or are at risk of dropping out. In his State of the City address last month, he promised to “begin creating more new schools, and new programs, that offer high school students additional routes to graduation, employment, and post-secondary education.” But he did not say what those programs might be.

Last week saw the release of the Preliminary Mayor's Management Report, the major way the the public can see how city agencies measure up. In the education section of the report, it was evident that, by the Bloomberg administration's own figures, the on-time graduation rate had decreased slightly -- from 54.3 percent (the figure cited during the campaign) to 53.2 percent.

This week, the State Education Department released its own graduation rate for the city, one that was far worse -- 43.5 percent.

The Bloomberg administration did list other statistics to indicate that "more students are opting to stay in school at least an additional year to work towards graduation." But it was hard to deny the continuing problem of dropouts, though the mayor seemed to try to deflect some responsibility for it: “We have to wait for those who did get the benefit of having the basic skills earlier in their educational career to arrive at the high school level,” he told reporters. “In the meantime, the numbers are going to go up and down and there’s no reason to think that you’re going to see lots of improvement until these things start kicking in.”

WHY STUDENTS LEAVE

Reasons for dropping out are “as varied as the kids,” said JoEllen Lynch, executive director of the Department of Education’s Office of Youth Development and School-Community Services. “Things come up in their lives, and sometimes school can’t meet their needs.” Some of this is just part of adolescence. “I think they’re always wondering why they have to be in high school,” Lynch said

“Everyone’s got their own story. But the common things are they feel alienated from school. And there are family pressures,” said Nancy Romer, a Brooklyn College psychology professor and executive director of the Brooklyn College Community Partnership which runs after-school and weekend programs for high school students. (See story about this program, Luring Students with Fashion and Flash on the Community Gazette serving East Flatbush)

Outside Pressures

New York’s failing students confront the array of problems that many poor people in the city grapple with. Some students need a job. Others must care for younger siblings, sick relatives or their own children. And their parents, perhaps juggling several jobs and barely making ends meet, may have little time or energy to make sure their teenager goes to school. Students in particularly stressful situations -- such as being homeless or living in foster care -- are more likely to drop out.

Lost in the Shuffle

Even after Najsha Chacon stopped attending classes at Fort Hamilton High School, she rarely saw a counselor. The school sent postcards home but she intercepted the mail. No one called to alert her father of the problem. Among 4,400 students, she was not likely to be missed. (For more on her story, see Bringing Dropouts Back on the Community Gazette serving Red Hook.)

“Often in school, there’s such pressure to achieve, they don’t have the time to pay attention emotionally and socially to kids,” said Romer.

The situation can be particularly difficult for youngsters who need extra help or for those who do not speak English. (See related story, Helping Immigrant Teens Stay In School, on bilingual Luperon High School in the Community Gazette for Washington Heights.)

Academic Woes

Many students enter high school unable to do high school work. They may fail their ninth grade classes a couple of times -– and then give up. School enrollment figures for 2004 tell the story. Each grade from one to eight had about 75,000 students. Then, in ninth grade the number of students mushroomed to 103,000. But many students apparently got no further. Only 82,000 students enrolled in 10th grade and 41,000 in 12th.

Students find the move from junior high school to high school extremely difficult, said Susan Matloff-Nieves, associate executive director for youth services at Forest Hills Community House. In junior high school an adult or two watched out for them. That is rarely the case in the larger world of high school.

For whatever reason, students at some schools are far more likely to drop out than students elsewhere. “What stands out in New York City is not only the sheer concentration of poorly performing high schools, but how low” the graduation rate is in some schools, Robert Balfanz and Nettie Letgers of John Hopkins University wrote in a 2004 study (in pdf format): “For the class of 2002, there were more than 30 high schools in which the senior class was less than one third the size of the freshman class four years earlier.”

Pushed Out

For some students the decision to leave was not voluntary. In 2002, Advocates for Children and the public advocate’s office found that between 1998 and 2001 some 160,000 student were “pushed out” of school, many because they had low grades and seemed unlikely to graduate; by pushing them out, the schools' overall scores would look better. After the organization filed suit, the Department of Education, while not admitting any guilt, instituted policies to address the problem.

But Advocates for Children says the pushing out continues. Last summer, it filed suit against Boys and Girls High School in Brooklyn, charging it had illegally excluded students.

WHAT IS BEING DONE

Improving the Schools

As the mayor’s comment on the latest dropout figures makes clear, he and schools chancellor, Joel Klein believe their overall reforms will eventually bring the dropout rate down.

But some question how much improvements in lower grades will help. A 2004 study of Chicago schools concluded that focusing reforms on elementary schools and ending social promotion did not lead to substantial improvements in the graduation rate. “Low performing high schools cannot be fundamentally improved by attempts to â€inoculate’ children early,” write Balfanz and Letgers” – if traditional large neighborhood high schools remain intact.

But Bloomberg and Klein have shut some of the large high schools, particularly ones with low graduation rates, and replaced them with small schools. The theory is that small schools provide students with more attention and keep better track of them. In small schools, “people develop relationships with one another. Teachers can use those relationships to leverage better performance,” said Jacqueline Ancess, associate director of the National Center for Restructuring Education, Schools and Teaching at Teachers College. (See a related story, Building Community in a Cramped Space , about one small school, Banana Kelly High School, in the Community Gazettes for Hunts Point and other South Bronx neighborhoods.)

But Ancess cautioned, size is not enough. “If you re-create bigger schools in smaller versions, you’re not going to see much of a difference,” she said.

Although many small schools have not existed long enough even to have had a graduating class, there are indications that small schools hold on to students better. Unfortunately, they do not necessarily make those students perform better, said David Bloomfield, head of the Educational Leadership program at Brooklyn College and a parent member of the Citywide Council on High Schools.

He worries that many of the students at highest risk of dropping out -– particularly special education students (in pdf format) and those learning English -- are the least likely to benefit from the administration’s reform.

Despite the emphasis on the small high schools, most city students attend larger schools and, Bloomfield said, the Department of Education does not seem to have plans for improving them. Instead, he said, they have “filled some schools with even more kids and cops.”

Offering Extra Help

Many programs have sprung up seeking to address the deficiencies at so many public high schools.

They try to create “an environment that’s conducive to learning, an environment where [students] can lead with their strengths,” said Jim Marley, assistant executive director of Bronx community programs for Good Shepherd Services.

T

T

To get students to attend, they offer things kids like before moving on to homework help, test prep and counseling. The Hot Spots program run throughout Queens by Forest Hills Community House features sports, hip hop, break dancing and the like to attract middle and high school students to its programs.

The Brooklyn College Community Partnership program uses arts as the lure, and Robin Redmond, director of youth & immigration services for the Flatbush Development Corporation decided that, as long as kids were spending evenings in a school gym playing basketball, they might as well get some academic help as well.

The United Way’s Community Achievement Project in the Schools works with several thousand middle and high school students who have been absent 27 to 75 days a year, which puts them at risk of dropping out. Working with community-based organizations, it provides counseling for students and their families. Last year, 49 percent of the students involved improved their attendance.

Making The Job Link

Young people find it “difficult to make the connection between what’s happening in the classroom and future success,” said Matloff-Nieves.

Cooper Small, the Stuyvesant dropout, did not think school would help him with his career -- and he may have been right. Small, profiled in the book The Case Against College, managed to make $175 an hour -- and get admitted to college -- without a diploma. But most students are not so fortunate, and thus many program seek to help kids make the link between school and career.

City as School, run by the education department for students at risk or dropping out offers work experiences with businesses, non profits and government agencies.

Good Shepherd Services oversees two mentoring programs in Bronx high schools -- one which places students at high schools with high dropout rates at the Ernest and Young accounting firm, the other with the Bronx district attorney’s office.

And the Flatbush Development Corporation plans to launch a program at Erasmus Hall High School – a huge high school that has been broken into smaller “academies” – to provide college and career information to the predominantly low income students, many first generation Americans of immigrants. “We want to be the parent and mentor the school cannot be, “said Robin Redmon, director of education program’s for the corporation.

If you “engage young people in their future,” said Lynch. “You can excite them into re-engaging in learning.

"Transfer" Schools, The "GED," And Other Programs

Between the time a student drops out and reaches aged 22, the city offers several programs to try to get them back on track. Najsha Chacon attended one , South Brooklyn High School in Red Hook, and received her diploma in December. She now hopes to attend college and become a teacher.

For students who must work or take care of a child during the day, the Department of YABC program allows them to earn their diplomas at night. Beginning in September, the city added a Learning to Work program to provide vocational training at some of the YABC centers.

And many young people attend GED classes. Students can stay until they reach age 22 or pass the test. Alexandria Stewart, who dropped out of Curtis High School, recently began attending one of the classes -- run by the Flatbush Development Corporation -- at Brooklyn’s Ditmas Junior High School. Many students in Stewart’s class see the GED as an ideal alternative to school –- less class time, fewer hassles and in this particular case, thanks to evening classes, a way both to go to school and sleep late in the morning.

Others see shortcomings. “You miss so much by not being in high school,” Redmond said. “You miss the socialization. And if you don’t know how to get along with others, how are you going to get a job?”

But for students nearing age 21 and far behind in earning the number of credits, the GED may be the most effective path.

No single one of these program works for everyone. Few, if any, serve the students most in need –- those who read at an elementary school level, or worse. The people who work with dropouts or likely dropouts say the real solution lies in more resources for school and more attention being paid to the needs of city students, particularly poor and minority children. “The hope would be as you go on we will need fewer and fewer of the [special] programs,” said Lynch. But, she added, “There may always be a reason a young person needs something extra in life.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Articles and Reports

The Class of 2004 Four-Year Longitudinal Report and 2003-2004 Event Dropout Rates The Department’s of Education’s most recent analysis (In PDF Format).

High School Drop Out Rates in the United States (Manhattan Institute, 2002) This study by Jay Greene develops a new method of computing the dropout rate and, using it, determines that only 74 percent graduate nationwide.

Keeping Kids in School(American School Board Journal, December 2002)

Schools can do the most to keep kids from droping out.

Learning Disabled (City Limits, February 2002)

With the state setting tighter graduation requirements, more city students are leaving school to get a high school equivalency diploma rather than the real thing.

Leaving School Empty Handed: A Report on Graduation and Dropout Rates for Students who Receive Special Education Services In New York City (2005) A report by Advocates for Children examining data from 1996 to 2004.

Locating the Dropout Crisis (2005)

This study by two researchers at the Center for Social Organization of Schools at The Johns Hopkins University looks at how few of American’s high school freshmen graduate four years later -- and why.

Losing Our Future (Harvard Civil Rights Project, 2004)

A report on how the nation’s drop out crisis disproportionately affects blacks and Latinos.

Out of School, Out of Work … Out of Luck? (Community Service Society, 2005)

A study of the approximately 170,000 New Yorkers aged 16 through 24 who are neither working nor attending school.

(School Improvement Research Series. 2001)

This report finds that the dropout problem is complex and requires a complex array of solutions.

Reinventing High School: Outcomes of the Coalition Campus Schools Project(American Educational Research Journal Fall 2002)

An assessment of a 1990s program to replace large failing New York high schools with smaller schools.

School Push-Outs: An Urban Case Study(Clearinghouse Review Journal of Poverty Law and Policy; January-February 2005)

An article by Elisa Hyman of Advocates for Children on the city’s alleged efforts to encourage poorly performing students to leave school and legal efforts to fight it.

Programs

The After School Corporation

Provides grants, training and assistance to community groups running after school programs, including some aimed at dropout prevention, in New York City schools.

Brooklyn College Community Partnership

A network linking the college to the Brooklyn community, it runs after school programs at a number of Brooklyn schools and offers an arts program, which also provides tutoring and counseling, for middle and high school students at the Brooklyn College campus.

Coalition of Essential Schools

An organization that seeks to encourage the establishment of more personalized schools. Has been involved in the small school movement, including the Coalition Campus Schools in New York City.

College Now

A collaborative initiative of the City University of New York and the Department of Education designed to ensure that graduating students are ready to do college-level work.

Community Achievement Project n the Schools

A project of the United Way in which community organizations across the city work to help at-risk students stay in school.

Flatbush Development Corporation

Runs mentoring and career counseling programs for high school students and GED classes in Central Brooklyn.

Forest Hills Community House Runs a variety of after school and other services for middle and high school students.

Good Shepherd Services