The New High Schools Admissions Process

By November 14th, thousands of New York City eight graders must submit official applications listing their high school choices. The Department of Education has scheduled new information forums for parents and students in each borough. Chancellor Klein and company are belatedly trying to stem some of the confusion that has arisen from the initiation of a new high school admissions process at the beginning of the school year.

The new high schools admissions process was implemented this fall with neither public announcement nor public vetting. As students, parents, guidance counselors, and administrators at both middle and high schools scrambled to learn the details of the new policy, misinformation and frustration reigned. Only now are people starting to understand the new system.

The new admissions process was designed to be fairer to more of the 100,000 students who apply to public high schools each year. Beginning this year, students will rank 12 schools on their applications in order of preference. Unlike previous years, high schools will make their acceptance decisions without knowing how their school was ranked on a student's application. A complex computer program will match up students with their highest ranked school that also accepts them. The program is designed like the one that matches medical school graduates with residency programs (though the mechanics of the schools' matching process have not been made public). There are no more waiting lists. The one school with which a student is matched will be the only option students will be offered unless they are accepted into one of the specialized high schools, which have separate admissions processes.

Few would question the need to reform the city schools' high schools admissions process, which, in previous years, gave top students several school choices but sent thousands of other students to schools not on their list of preferences at all. Klein and company addressed the problem quickly, but they have provided limited public explanation or justification of the details. And they have not adequately prepared for the effects of the changes. The result is considerable anxiety for parents and schools alike.

What can the Department of Education learn from this?

School personnel must be able to provide accurate information about new policies. Some families found sound, reliable information about the new policies, like Insideschools.org and the Web site and handbooks produced by the Department of Education. However, many others depended on school personnel who, not infrequently, gave out wrong or contradictory information.

Better school data are needed too. Because students must list 12 high school choices (instead of five in previous years), they and their families need to learn about many more options. With students selecting a larger number of schools, they will have to look further afield, beyond the schools with which they or people around them may be familiar. To help, the high school directory should include school safety information and other basic information about school conditions now listed only as statistics on school report cards. In addition, if schools are going to continue to give preference to certain students, the directory should not only state schools' priority groups but should also give data about how many students beyond those groups are actually accepted.

Students and parents must be able to get a firsthand look at the schools. This year, schools were totally unprepared for the much larger number of students and parents attending scheduled high school open houses and tours. As a result, many of these sessions have been overcrowded and many schools unable to accommodate the number of families that wanted to visit. In the future, schools must be accessible and offer sufficient tours and open houses to accommodate prospective students and parents.

All families need to know schools' true admissions processes. As might be expected, both parents and schools are jostling to gain whatever advantage they can under the new system: They are trying to figure out how to maximize the chances that they will get their top choices, whether of schools or of students. Parents report that some schools are trying to retain the advantages they had under the old system by creating ways for students "in the know" to submit additional information about their preferences and qualifications. Many parents welcome this because they are worried that, with a larger pool of applicants, schools will make their choices based on a more limited set of criteria, judging students solely by tests scores, grades, and attendance records. But these practices may put families who go by the book at a disadvantage.

With such a wide variety of New York City public high schools, the choice of a high school is a very important one. Many city high schools are just plain bad, and many more are mediocre. Even among the good schools, there are important differences--in size, in philosophy, in curricular and extracurricular offerings. Is the reform going to be a real improvement? No one can yet say whether the new system will get the intended results or what other unintended consequences may arise. The new admissions process may ensure that the system by which students are distributed to schools is fairer to more students. Unfortunately, no admissions process is going to solve the basic problem that there are not nearly enough good high schools to go around.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and the director of policy development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and the director of policy development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity.

Josh Simons is an artist and designer with two children in the public schools. The views expressed are their own.

Class Size Limited By Law?

Concerns over the number of students per class took on a new magnitude and urgency last month – and will come even more to the fore next month, when the issue of class size will be on the November ballot.

When the new school year started in September, parents, teachers, and advocates who thought that the public schools were already about to burst found classrooms more overcrowded than ever.

Many elementary school teachers, who last year struggled to meet the needs of 28 or 29 students, are now responsible for 33 or 34. And dozens of overcrowded middle and high schools also find themselves with five or more extra students per classroom. The United Federation of Teachers, the teachers union, claims to have counted over 10,000 classes that violate the union contract's class-size limits, which range from 25 in kindergarten to 34 in high school. The union has filed a formal grievance against Chancellor Klein and the Department of Education for these contract violations.

Reasons for the extreme overcrowding this year include growing enrollments and the effects of the federal No Child Left Behind legislation, which allows students from schools that score poorly on state tests and are labeled "in need of improvement" to seek transfers to better schools throughout the city. Last year, 331 of the city's approximately 1200 schools were so labeled; this year, the list includes 497 city schools--and students at 374 of them are now eligible for transfers.

New York City classes have long been by far the largest in the state, with class sizes averaging 20 to 35 percent over other school districts. This fact contributed to the recent New York Court of Appeals ruling in CFE v. the State of New York (In PDF format) that the students of New York City were being denied their constitutional right to a sound basic education. In that decision, Chief Judge Judith Kaye acknowledged that "New York City schools have excessive class sizes, and that class size affects learning."

Class-size-reduction advocates believe that large classes are the New York City schools' most serious problem. They point to studies that show that smaller classes lead to more individualized attention and improved student achievement, especially for poor and minority students. They contend that smaller classes also foster greater parent involvement, fewer disciplinary problems, and lower drop-out rates.

Soon New Yorkers will get a chance to vote on one potential solution to the city's class-size problem: amending the New York City charter to make smaller classes mandatory by law.

In August, a group called New Yorkers for Smaller Classes, which includes the teachers union and a number of parent and advocacy organizations, submitted a petition calling for a referendum on class size to be placed on the ballot in November. The referendum would ask voters to approve the creation of a city charter revision commission to study the class-size issue and to decide whether a proposition to limit class size should go before New York City voters in the 2004 election.

While few deny the disadvantages of large classes, not everyone supports this type of solution to the problem. Critics of the idea argue that reasonable class size is just one of a number of ingredients necessary for a quality education; they worry that legislating small classes does not ensure and may even jeopardize having enough qualified teachers, adequate school buildings, and the full range of programs that students also need to succeed.

Opponents of the class-size ballot initiative point to Florida's controversial class-size amendment, which was approved by voters last fall. The amendment requires school districts to begin reducing class sizes this year. By 2010, classes can be no larger than 18 in grades pre-K through 3, 22 in grades 4 through 8, and 25 in high school. In a year with limited state funds, however, some believe that teachers' raises, school construction, as well as school programs in art and music have been jeopardized by the class-size mandate. A movement is now underway to scale back the law, though there is doubt whether the still-popular law is vulnerable to repeal.

New Yorkers, however, will vote in November on whether to start the city on the path toward its own class-size ballot initiative. Although last month the city clerk bumped the class-size referendum from the ballot on the grounds that only one charter proposal is permitted per election, and the mayor's charter question on nonpartisan elections had priority under local election law, New Yorkers for Smaller Classes filed suit and prevailed. On October 2, State Supreme Court Justice Louise Gurner Gans put the issue back on the ballot. City officials say they will appeal her decision. In the meantime, though, New Yorkers for Smaller Classes is now preparing for an all-out campaign to win the vote.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and director of policy development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a coalition advocating for a sound basic education for students in New York City. The views expressed are her own.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and director of policy development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a coalition advocating for a sound basic education for students in New York City. The views expressed are her own.

Struggling With Strollers and Schools

Leaving New YorkWhile some New Yorkers are leaving the city, citing bad schools, high housing costs or the daily stresses of urban life, analysts debate whether the exodus is anything alarming or unusual, and what to do about it.Why New Yorkers Are Leaving: The City Is Too Expensive by E.J. McMahon City Schools and Housing Are Inadequate by David Kallick New Yorkers Who Left: Rondrae Hunter A Frustrating Apartment Search David Bassine Fear of Terrorism Stefan Kochi Bad for Business |

There were a lot of things that made me tired of city life, like struggling to get my stroller up the subway stairs. Try to take a stroller on a bus, and see whether you feel like ever getting on a bus again. It seemed like such a battle to stay in New York. If we weren't getting to enjoy things like performances at City Center, and all the things the city is about, there wasn't much point in being there. When you have really young children you can't enjoy the cultural life of the city anymore -- at least, we couldn't. I couldn't stay awake past nine o'clock.

School was looming. We couldn't afford private school, certainly not for two children. And I felt I was having hostile interactions all the time with people in the city: Cab drivers who wouldn't take me the way I wanted to go, etc. I got tired of it, so I left.

At the time, my husband and I owned a little building in Greenpoint that we were going to move into. Then we realized that we could live a lot better if we rented the building out - it had three apartments - and used the money to live somewhere where the cost of living was lower. We could use the public schools, or private schools that cost half or 30 percent what they do in the city.

Our income at the time came from the rent from the building in the city. My husband is an artist, so he just continued his work. I was pregnant with my second child, so I wasn't working at all. Since then I've taken a class and become a real estate appraiser, which has worked out well.

Now I live in a hamlet called High Falls. It's in Ulster County, eight miles south of Kingston, the same distance northwest of New Paltz. There might be 1,000 or 1,500 people in High Falls. I live in a small house, 1,100 square feet. But it's an old house, a turn-of-the-century farmhouse-type thing, with a porch and a beautiful garden. The town has a noon whistle.

I always thought the city was a good place for children to grow up, and I still think that. I grew up in Chelsea and on the Upper West Side. It is such a rich environment in many ways. But I also like the childhood my kids are having, and in retrospect I can see a lot of things that I missed out on, such as any chance to really do sports, or know anything about the natural world. I didn't have pets, if I don't count rodents. I never had dogs, certainly never had anything like a horse. My kids don't have horses, but they have friends who do.

They like it up here. My older son, who is eight and lived in the city as a small child, will sometimes say things that really astonish me. When it's the first snow of the season and there are icicles hanging off the trees, he says, "I'm so glad I live here, because if I lived in the city I'd never get to see this." It strikes me as funny that a kid can even think that way.

But I feel the same way. I can't imagine living in New York anymore. I find it overwhelming. I find the number of strangers disconcerting. I'm no longer used to not being known in places where I go. And aesthetically the city is difficult. A lot of it is dirty, ugly and noisy. I was starting to feel that way when I lived there. But the feeling developed more strongly afterward.

I grew up in New York and for years I just didn't realize that Manhattan was not the center of the universe. I don't feel that way anymore.

Alison Woods was born in Manhattan and moved upstate in 1997.

A National Theater at Ground Zero

More than 70 arts groups responded to the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation’s invitation to move to Ground Zero, but the one making headlines came from an organization that does not yet exist—the American National Theater.

Proposals also came from El Museo de Barrio, for a Hispanic cultural center; from Hunter College, to create a downtown arts campus; and from UrbanGlass, a contemporary art glass center now housed in a small space in Fort Greene. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation will work with the Department of Cultural Affairs and the New York State Council on the Arts to evaluate the proposals, though how and when are not clear. For arts groups, there is a great deal at stake, including as much as $200 million in public funding and the chance to set up shop on the world’s most famous stage.

The proposal for an American National Theater is in some ways as optimistic -- some might say naĂŻve -- as the creation of a World Trade Center three decades ago. The project is headed by a little-known actor named Sean Cullen and has been endorsed by Arthur Miller, Blair Brown, Emily Mann, Harold Prince, and others. Cullen envisions it as a showcase for the best of what the regional theaters have to offer, selected from the 72 members of the League of Resident Theatres and some 80 other major theaters throughout the country by theater professionals hired as jurors. An artistic director would then choose 15 plays to form the season on the national theater’s three stages, with 800, 700, and 400 seats.

The idea taps into the theater person’s perennial frustration. Most live in New York but, because they can’t make a living Off Broadway, spend their career on the road in Minnesota, Texas, and Oregon. Very few productions make it to New York, and even fewer arrive with their casts intact. While Europe sends its national theaters—many with resident acting companies—on tour, American theater people work largely in artistic isolation.

Perhaps the earliest attempt to found a national theater came in the 1920s, when the critic John Corbin founded the New Theatre in New York. In search of a homegrown “American” aesthetic, he read thousands of scripts from would-be playwrights across the country. The project never made it off the ground.

There were several more attempts in the mid-1980s, when Peter Sellars took the reins at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont; Joe Papp proposed to fund such a theater through the sale of air rights over Broadway houses; and Actor’s Equity hoped to seed the country with “mini” national theaters.

Given this history, it’s not surprising that many theater professionals have voiced reservations about Cullen’s proposal. At a time when even long-established nonprofits are struggling, there are obvious concerns about how a national theater would be funded. Virginia Louloudes, executive director of the Alliance of Resident Theatres/New York, points out that there is only a finite amount of money to go around, and yet many deserving New York theaters. Cullen estimates that the national theater would cost about $170 million and have an annual budget of $17 to $20 million, financed by private, corporate, and foundation support. In addition, he would create an apartment tower to raise rental revenue for the theater.

Ben Cameron, director of Theatre Communications Group, has expressed concerns about the fairness of the selection process. Even if jurors saw 150 plays a year, that would be only a fraction of the work mounted at the country’s 1,800 nonprofits. The regional theaters—which arose in the 1960s to challenge the dominance of New York theater and the commercial prerogatives of Broadway—have themselves been challenged by smaller, less institutional theaters in cities like Austin and Seattle that reject the demands of a subscription audience and institutional model. And, while many regional theaters consistently produce original, quality work, others copycat each other and produce whatever new play has been hot and crowd-pleasing that season.

Because theater occupies only a marginal place in our society, theater people would want to enshrine it in some way. But it will take some extraordinary resources and a leap of faith to create one. As Newsday critic Linda Winer wrote recently, “There is nothing inevitable about the notion of a national theater. We are not automatically less of a civilization without one.”

Catch the FEVA

To judge by this summer’s HOWL! Festival, high rents and Starbucks have not diminished the East Village’s role as a crucible for counterculture. In all, more than 100,000 attended the festival’s 262 music, performance, film, and poetry events.

For the younger crowd, the festival served as a primer to East Village history—a 3-D slide show of the neighborhood in the 1980s, a video of the Tompkins Square Park riots, a panel on art moderated by Karen Finley, and the publication party of a book about the history of film and video on the Lower East Side.

The festival was produced by the Federation of East Village Artists, a new group that aims to honor and promote the neighborhood’s cultural legacy. Executive director Phil Hartman says that FEVA plans to leverage its new visibility to push for broader social goals, which include advocating for better health insurance and housing for artists, improving arts education in local schools, and bringing more public art into neighborhood streets.

The group also plans a Museum of the Counterculture, part archive, part gallery, and part performance space. Among other things, it would seek to preserve the collection of filmmaker Jack Smith, (whose Flaming Creatures was shot on the roof of a Lower East Side movie house) and the beat poet Ed Sanders, whose papers are, according to Hartman, “in [Sanders’] leaky garage upstate.” They are also in the process of raising money to create an emergency relief fund for the many downtown artists and organizations fighting for survival.

But FEVA doesn’t plan simply to worship at the altar of Allen Ginsburg. “ We’re defining the East Village spiritually, not geographically,” Hartman says. “Next year we hope to include more of the Brooklyn scenes, Long Island City, da Bronx, wherever good, crazy stuff is happening.”

Martha Hostetter has written about the arts for the Village Voice, American Theater and Empire New York.

Bake Sales Are Not Enough Anymore

Stan Levenson, a fund-raising consultant, often asks audiences at his lectures if they ever hear from the colleges or universities they attended. Of course, the crowd acknowledges. How about private schools they attended? Yes. Do they ask for donations? He doesn't even have to wait for the answer to that one.

"Every day, people are giving to good causes," says Levenson, whose clients are educators. "Why not public schools?"

Alumni of universities and private schools have been hit up for years -- most have entire departments devoted to fund-raising, called development offices -- but public schools are only starting to pursue fund-raising strategies that go "beyond the bake sale," as Levenson might say. With New York City facing tight budgets and increased pressure to provide a quality basic education to more than one million students, many members of the public school community think they have little choice but to seek private help.

When it comes to having successful alumni with deep pockets, elite public schools like Stuyvesant High School have the potential to go toe-to-toe with private educational powerhouses such as the Peddie School in New Jersey, which raised over $1.25 million in 2002. While most New York City public schools do not have the donor pool of a Peddie or a Stuyvesant, relying instead on traditional fund-raising events like carnivals and bake sales, some have begun to launch pledge drives and mail campaigns to fill in the gaps left by shortfalls in public funding. To boost such efforts, the Department of Education has launched a web site (Fund For Public Schools) where alumni of city schools can find out how to donate time or money.

The Parents Association at PS 87 on Manhattan's Upper West Side, raised approximately $300,000 in grants and donations. While the Department of Education reviews the Parents Association budget, it gives the school wide discretion in fundraising.

From a pledge drive, to auctioning off the chance to be principal for a day, to holding a neighborhood street fair and talent shows by parents and students, PS 87's fund-raising efforts help the school meet basic needs. The money buys Band-Aids and paper towels for the nurse's office, helps pay the school librarian and the "lice lady," and funds the arts program. The association's funds also cover the salaries of two kindergarten aides.

"It's pretty stark, what you'd have to do without" if there was no fund-raising, says Fredda Rosen, co-president of the elementary school's Parents Association. "You'd have reading and math."

While schools have always done fund-raising, the demand for outside money has increased. "There has always been fund-raising for public schools, but in the past, it's been for window-dressing," says Howie Schaffer, media director for the Public Education Network, a Washington-based group that lobbies for increased funding for public schools. "Now, the situation is so dire and the pain of the financial cuts is so acute that you're seeing these [funds] move into programs."

PS 87 benefits from having a cross-section of wealthy, middle class and working class families, nearly 50 percent of whom contributed to the pledge drive last year. But many schools, including those where the need may be greatest, are not so fortunate. And so some critics worry that the increased reliance on grassroots fund-raising broadens the gap between "have" and "have-not" districts.

"The danger is that if we allow elected officials to cut budgets, then only wealthy communities can ease that pain," says Schaffer.

In 1997, parents at PS 41 in fairly affluent Greenwich Village raised $46,000 to keep a teacher and hold class size down. Then-Chancellor Rudy Crew balked at the move, saying he was concerned about the effect using private funds to pay salaries of regular classroom teachers "would have on the sore issue of equity for all children throughout the system." Crew eventually compromised, saying the teacher could stay but that the community school district -- not the parents -- would pay the salary.

But issues of equity remain. While PS 87's Parents Association raises money for arts programs, one elementary school teacher on Staten Island is desperate for basic classroom supplies like notebooks, scissors, tape, glue and markers. One hundred percent of the students at the school qualify for free lunches. On the DonorsChoose web site, the instructor pleads for help: "Many children have a difficult time buying these supplies...this can cause missing work, as well as lack of self-esteem. Our students should not have to feel disadvantaged when it comes to their education."

DonorsChoose is a nonprofit that helps such underfunded schools find donors willing to pay for specific programs. Rich Yudhishthu, a teacher at Wings Academy in the Bronx, is director of operations of the web site. He and his staff review thousands of proposals from New York teachers looking for everything from "baby-think-it-over dolls" for a pregnancy prevention program, to erasers and chalk. Once a proposal is approved (and Yudhishthu notes that nearly all legitimate requests are), it is posted online in the hopes that a donor will fund it. The system is a kind of E-bay for the civic minded, boosted by word of mouth and some high-profile publicity from a profile on the Oprah Winfrey show.

Once a proposal is sponsored, DonorsChoose purchases the materials and gets them to the school, along with a disposable camera and a self-addressed stamped envelope in which to send photos of the funds in action, thank-you notes from students and a report from the instructor. Since the program's inception in the spring of 2000, over 700 proposals have been funded. More than half the faculty members at IS 125 in the South Bronx have had proposals funded.

Some fund-raising consultants believe city-wide efforts such as DonorsChoose are likely to be more productive than traditional school-based carnivals and book sales. But Levenson, the fund-raising consultant, advises individual public schools to ratchet up their fund-raising as well, setting aside some of their regular budget for a development office, much like private schools and universities do, to tap into successful alumni, parents, friends or community members. "In 18 months or two years," Levinson says, "these people's salaries will pay for themselves."

But for those in the thick of school fund-raising, Levenson ignores a valued result of more traditional grassroots fund-raisers: Community-building. "It makes the children feel like their schools matter," says Jean Joachim, former vice president of PS 87's Parents' Association, and author of Beyond the Bake Sale: The Ultimate School Fund-raising Book.

Challenging A Test The Teachers Must Take

At the conclusion of what federal judge Constance Baker Motley described as an "epic trial," discrimination claims brought against New York City's Board of Education and the New York State Education Department by black and Latino teachers and potential teachers were dismissed during the opening week of the school year.

The class action was brought in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York by Elsa Gulino, Mayling Ralph, Peter Wilds and Nia Green on behalf of themselves and an unspecified number of individuals estimated by plaintiff's counsel to be between 3,500 and 5,000. The lawsuit challenged tests introduced in 1991 as part of new state legislation mandating that anyone who did not already hold a full New York City license had to obtain state certification.

One aspect of certification entailed passing a two-part test. Plaintiffs had met all other requirements, including attaining master's degrees, but could not receive full teaching certification without passing the tests.

The lawsuit charged that the tests did not accurately measure ability or predict classroom success, and were not necessary for the teaching positions, thereby rendering the tests and the use of the tests invalid. The claims of discrimination were that white applicants passed in far greater numbers than blacks and Latinos due to cultural bias in the tests and inconsistent grading. The tests, they argued, had a disparate or adverse impact on black and Latino candidates for permanent certification to teach in New York City public schools. Without certification even people who were already teaching, some for as many as ten years, became ineligible for full licenses; others lost their temporary licenses. Some never made it into the school system. Those who did retain permanent substitute positions nevertheless experienced reduction of employment and promotion opportunities, and as much as a 30 percent decrease in salary and benefits.

"Disparate impact" in employment discrimination litigation, requires the plaintiffs to prove that the tests had an adverse effect on a protected class, the racial and ethnic groups of which they are members, i.e., black and Latino teachers and teaching candidates. They had to establish that "a particular employment practice (in this case the tests) caused a disparate impact on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin."

In fact, plaintiffs did establish this claim. In her 34-page Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Judge Motley -- who half a century ago, along with Thurgood Marshall, was counsel to the plaintiffs in Brown v Topeka Kansas Board of Education, a landmark in civil rights and education law -- found that disparity was demonstrated in this case, known as Gulino, for the first named plaintiff. The pass rates by whites was greater in a statistically significant way than that for test takers in other groups. Expert testimony showed that if blacks and Latinos had achieved pass rates equivalent to whites, their representation in the teacher workforce would have been greatly increased.

"The tests," said Barbara Olshansky, of the Center for Constitutional Rights, who represents the plaintiffs, "had a staggering effect on screening out teachers of color."

But the case did not end with the finding of disparate impact on members of a protected group.

In the second part of her analysis, Judge Motley concluded that the defendant employers overcame the disparate impact because the tests have a "manifest relationship" to the employment and legitimate connection to the goals of the teaching function.

The test contained multiple choice questions in mathematics, science and the liberal arts, and a short essay, which counted for 20 percent of the total grade. Some of the plaintiffs had passed the essay portion but not the short answers, others had lost ground on the essay. Judge Motley's decision focused on the essay.

"Defendants' decision to exclude those who are not in command of written English is in keeping with the educational goal of teaching students to write and speak with fluency. It should go without saying that New York City teachers should be able to communicate in both spoken and written English. Teachers who are unable to write a coherent essay without a host of spelling and grammar errors they pass on that deficiency to their students, both in commenting on and grading the work they turn in."

The decision did not address those who have not passed the test but continue to be employed as full-time permanent teachers and what it means to the student body that they continue to teach. Thomas Ryan, executive director of the city’s Division of Human Resources, testified that when he decided to permit these teachers to continue teaching full-time after their licenses had been revoked, he "did not believe that the teachers were harming the students in any way."

Once the court found that the tests were sufficiently job related to overcome the disparate impact, the burden shifted back to the plaintiffs, to present another practical, cost effective alternative to the tests. The plaintiffs, who had argued that the tests were invalid and unreliable, put forward a "portfolio" concept in which teachers would work with mentors and be judged on their actual performance and what it would predict about their future performance. While the court was impressed with the possibilities of that approach, suggesting that perhaps it could be used in conjunction with testing, she rejected it as an alternative.

Marie DeCanio, a Board of Education witness, testified at trial, "A test does not a teacher make. Performance is obviously the best test of whether a teacher is qualified to teach ... . On the job performance is the best way." The judge, however, disagreed.

While Judge Motley found that defendants had made an insufficient showing of the validity of the tests, she held that the test in use since 1993 "was properly validated according to professional guidelines and standards, and that they had shown that according to education professionals, of all the skills required of teachers, the ability to write a coherent essay was most important."

Plaintiffs are planning an appeal. The spokeswoman for Corporation Counsel which represented the city, refused to comment, saying she was "too busy to discuss this case." The state was represented by the Office of the Attorney General.

. Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

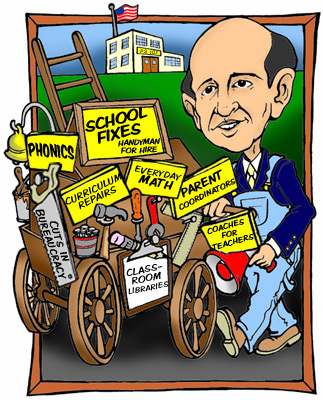

School Reforms of 2003

|

"A tremendous number of schools aren't making the grade," Peter Kerr, a spokesperson for Klein told the New York Times. "We're talking about hundreds of schools and thousands of families that are dealing with failure."

In an effort to address that, Klein and his team have spent the last 10 months completely overhauling the school system. Under their "Children First" initiative, they have changed the Department of Education's administrative structure, virtually eliminating the 32 community school districts and replacing them with 10 instructional divisions. Entire offices at the Department of Education were shut down in an effort to do away with excess bureaucracy. The mish-mash of disparate curricula that existed has been tossed out in favor of a uniform new curriculum for math and literacy.

Some see the full-speed-ahead approach as the only way to bring reform to an enormous, bureaucratic and complex system. Others say that there has been too much change too quickly, creating disorganization and confusion. Some see the reforms themselves as innovative and ambitious. Others find them untested, poorly designed and just plain wrong.

Revamping The Bureaucracy

The Department of Education recently held a "Parent Academy," a week-long training session for the city's 1,200 new "parent coordinators," one for every school, hired over the summer to boost parent involvement. Many of the new parent coordinators arrived for their training bright-eyed and energized. "What do I do with the courage and excitement I'm feeling right now?" one man said.

But the new coordinators also had plenty of unanswered questions. "It seems that there is a lack of understanding about my position and what it entitles me to do," noted one, echoing the concern of many of her colleagues. Some parent coordinators remained unsure what their budget was, or whether they even had one.

Their confusion is typical. The overhaul has created thousands of new positions even as others were eliminated. The 32 community school districts still technically exist, largely to comply with state law, but their offices have been whittled down from a few dozen administrators to just three employees

The 10 "instructional divisions" each consist of between two and four of the old districts. Until now, parents went to their district office when they had questions that could not be answered at the school level. Now, they go to "learning support centers" -- new offices in the instructional divisions.

But staff at the learning support centers may not have answers to pressing questions about registration, transfers, after-school programs and other key subjects. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum released a survey that found learning support center workers could not answer common questions. The report found, for example, that in a telephone survey of all ten support centers, none could answer questions about the documentation required to register a child.

Klein has conceded that many people in the system are learning on the job. "The fact that you don't get an answer immediately is not a major issue," said Klein. "The fact that you get an answer is critical."

Rosalyn Inman, a parent coordinator from Brooklyn, echoed Klein's sentiments. "Most of what we are going to need to know," she said, "we will learn as we go."

Advocates anticipate that, over time, the kinks will work themselves out. "Change is painful," notes Noreen Connell, executive director of the Educational Priorities Panel. "Might as well get as much as possible done in one, miserable year."

The New Curriculum

The real work of the school system, of course, goes on in the classroom. The standardized curriculum for all but about 200 of the city's so-called "high-performing schools" addresses that.

Until this year, districts and even individual schools selected their own curriculum. The lack of a standard approach posed particular problems for students who frequently transferred. With no clear guide, schools often switched from one curriculum to another, confusing students

Whatever the merits of the programs selected, some advocates say that Klein has taken a huge step forward by standardizing the programs for teaching literacy and math. "Every school was 'reinventing the wheel,' and some failing schools were reinventing the wheel every two years and doing it very poorly," said Noreen Connell. "Now consistency and depth in delivering instruction is a real possibility for most schools."

In literacy - reading and writing - the curriculum teaches children to read by having them read books that interest them. Under this approach, called "balanced literacy," Dick and Jane are out, replaced by classroom libraries where students can select books at their particular reading level.

The math program emphasizes problem solving over memorization and focuses on the way math is used in real life. Students use "manipulatives" such as blocks, rods and games to learn math concepts. For example, rather than being presented with a sheet of problems to learn addition, first graders might play a game with dice.

The new curriculum relies on what are generally viewed as progressive ideas about teaching. The math program, called "Everyday Math," emphasizes "understanding concepts rather than mastery of basic operations," and balanced literacy "focus[es] more on children working among themselves than on direct instruction," James Traub wrote in the New York Times.

Many experts have criticized the choice of the programs, charging that they do not give enough weight to traditional teaching methods. Using such programs in New York City schools could be "a disaster in the making," Sol Stern wrote in City Journal, "not least because the children in the targeted schools are mainly poor and minority - the very population historically most damaged by such methods."

Writing in the New York Sun, Bas Braams of the NYU mathematics department, faulted "Everyday Math" for offering a confusing array of methods for basic arithmetic, jumping around from topic to topic, and for introducing calculators in kindergarten.

More debate swirled around phonics, which teaches kids to read by emphasizing the relationship between letters and their sounds. Conservatives, including many in the Bush Education Department, favor this approach. But rather than endorsing a full-fledged phonics program, Klein and his educational expert, Diana Lam, decided to give students in lower grades a half hour of phonics instruction a day in addition to their other reading and writing work. Critics promptly charged that the program they selected -- "Month by Month Phonics" -- was untested, and, in fact, not focused on traditional phonics methods at all. In the wake of such criticism and threats from the Bush administration not to provide funds for the program, the school system selected a more traditional phonics program to supplement "Month by Month Phonics."

Klein has pointed out that the curriculum he and Lam chose is already being used in some successful city schools. Some of the city's highest performing districts, such as district 26 in Northeastern Queens, use balanced literacy. In March, the New York Times profiled P.S. 172 in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, a school that was already using both "Everyday Math" and balanced literacy, as well as phonics. The school has good test scores, despite a disadvantaged student body.

In discussing the math curriculum, school principal Jack Spatola said, "The beauty of the program is that it individualizes teaching and learning. That helps kids to understand a process rather than just regurgitating it."

Teacher Training

Beyond the substance of the new curriculum, many principals and experts have expressed doubts about how teachers were trained.

Over the summer, teachers received a compact disc that provided an overview of the new curriculum. And this year school started a few days later than usual to give teachers four days of training about the new programs. To help teachers as they go along, the Department of Education has hired math and literacy coaches for each school using the new programs.

Stephen Porter, the principal of PS/IS 226 in Bensonhurst, thinks the uniform curriculum will improve continuity as students move from grade to grade. But he does not think teachers had enough time to become accustomed to the new programs before putting them into use. While the quality of training was good, teachers need more time to absorb it, he said. "You want [teachers] to really think about it," Porter said. "Right now, it is difficult for them to think, they are working so hard just to keep abreast of what is going on. They are trying to keep a day ahead of the kids."

But Robert Klein, a local instructional supervisor in Queens' Region 4, says that the new programs have gotten off to "a smooth start... Teachers have organized rooms and are using the new strategies."

While the new curriculum went into effect very quickly, it will take far longer to see the effect of the reform. "Instructional change is hard," said William Stroud, the principal of the Baccalaureate School for Global Education in Astoria who worked on the new curriculum. "People are looking for a quick fix to the achievement problem. If our expectation is that we are going to see results in one year or two years, we are going to be disappointed. We should expect to see improved student achievement in three to five years."

Given the magnitude of the changes, what was most striking on the first day of school was how much remained the same. Students, many toting new backpacks laden with supplies, struggled to find their classrooms and loudly called out to their friends. Teachers welcomed students as principals tried to deal with the customary confusion of making sure children ended up where they were supposed to. Asked if this year seems different from last, a tenth grader at the Baccalaureate School shrugged her shoulders and offered, "I have a new math teacher."

But the city still has a huge student body with many needs, and a lack of resources. The perennial problem of overcrowding may be even worse than usual this year, prompting the United Federation of Teachers to file grievances charging the classes are so big they violate the teachers' contract. And so, the real test of Children First will be to see whether it can improve performance despite these immense challenges.

Deborah Apsel is a reporter with Inside Schools, a web site published by Advocates for Children.

Related Article

Put Class Size on the Ballot

The New York City public school system is undergoing major changes. But little progress has been made, writes Leonie Haimson, to fix the system’s most serious problem: large classes.

Judging School Reform

This month's opening of the public schools in New York City may well be the rockiest in memory. The city's long-troubled school system is in the midst of a top-to-bottom overhaul not seen since decentralization in the early 1970s. Most students will return to schools that are adjusting to both major administrative and instructional changes.

Key to the reforms enacted by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and put into place by Chancellor Joel Klein is a reallocation of power to a clearly defined and publicly accountable management team, leadership training and more budget autonomy for principals, and a uniform early-grade curriculum for all but the highest performing schools. These types of changes raise alarms for those who held power in the old system, and so it is clear that there are vipers waiting in the grass for this reform and this group of reformers to stumble.

New Yorkers should not rush to judgment on the changes made in the school system. With 40 district offices now consolidated into 10 regional centers and with a new curriculum being implemented in most city schools, no one should be surprised to hear of missteps in the first weeks and months of school this year. Those inevitable missteps will not be reason to return to the old ways of doing business. The old ways may have served certain interests well, but it routinely failed some 60 percent of the city's students who each year are unable to meet state-set standards.

In any such large-scale turnaround, there can be a tension between enacting swift reform to create urgently needed changes and taking the time needed to smooth the way by seeking the opinions and winning the support of those who will be affected by the changes. With children's futures slipping away with each month of the status quo, Bloomberg and Klein can justify opting to create reform as quickly as possible, even if by fiat. But with minimal effort at fostering community buy-in, they have to expect a lot of resistance.

In the present case, the pace of change has launched numerous complaints about decision-making secrecy and top-down control, as well as grave worries about the impotence of competent educators to make decisions about the schools and classrooms for which they are responsible. For now, these real anxieties should be tempered with an understanding that such means may be necessary in this early stage of reform. There may be no other way to turn the battleship around except through many hands working together on orders from on high. And there may be no other way of ensuring that issues that arise on the decks during the turnaround are reviewed and addressed for their system-wide ramifications.

City schools vary enormously in their capacity for quality leadership and instruction. Klein and company insist that they are committed to managing these different schools differently. This is wise. Functional schools should run themselves; dysfunctional schools should be managed carefully. Parents and others need to be vigilant here to make sure that autonomy is granted to the schools, leaders, and school leadership teams who demonstrate that they are accountable to their students.

And no one should confuse what is needed to make the important structural reforms now put into motion and what is needed for continual improvement of the quality of teaching and learning in classrooms. This includes a collegial environment, experienced pedagogues to provide instructional leadership and mentoring, investment in effective professional development, shared planning time for teachers, and long-term consistency.

New Yorkers will get an opportunity to express themselves on the overhaul of the school system in the November 2005 mayoral election. It will be fair to judge the Bloomberg-Klein reforms at that point.

At that time, the voting public should be prepared to look not just at test scores but beyond to other important indicators of school-level and system-wide improvement.

• Are teachers and principals getting ongoing training and support?

• Is the quality of the professionals in the schools improving?

• Are qualified faculty staying put, especially in the schools that need them most?

• Is a plan underway for systematic class-size reduction?

• Are there more pre-kindergarten seats?

• Has a capital plan been adopted to create sufficient additional safe, healthy, up-to-date facilities?

• Are schools more responsive and inclusive of parents?

• Is accurate, timely information about the school policies and practices readily available?

• Are struggling students receiving more support?

• Are more kids staying in school?

• Is the graduation rate rising?

In the short term, New Yorkers need to remind themselves how bad the school system had become before these reforms were put in place. Since the mid-1980s, the school system has been tracking high school students and reporting on their graduation success. In all that time, the high school graduation rate, arguably the bottom line indicator of success, has remained at just about 50 percent.

The school system is still drastically underfunded, overcrowded, and, subject to policies, like teacher transfers, that put the needs of adults over the needs of children. City and school officials must tackle these. State lawmakers must make good on the Campaign for Fiscal Equity school-funding decision and ensure that the city schools have adequate resources with which to accomplish their goals.

There is still much to be done. But the current reforms, combined with others already in progress, such as the initiative to create more small high schools should be given a chance to play out for the benefit of the city's schools.

Raymond Domanico is senior education advisor to the Metro NY Industrial Areas Foundation.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and Director of Policy Development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a not-for-profit coalition working to reform New York State's education finance system to ensure adequate resources and the opportunity for a sound basic education for all students in New York City.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and Director of Policy Development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a not-for-profit coalition working to reform New York State's education finance system to ensure adequate resources and the opportunity for a sound basic education for all students in New York City.

The views expressed are their own.

New Studies About Immigrants

Since the terrorist attacks two years ago, immigrants have become the object of fear and rage, and, increasingly, the subject of research. Both groups opposed to further immigration and those who advocate for immigrants try to buttress their arguments with the steady flow of reports, studies and findings from think tanks and universities. Four recently released reports, two of them about housing, should give both sides in the debate some fresh ammunition.

IMMIGRANTS AND HOUSING

Latinos are most affected by the lack of affordable and low-rent housing in New York City, according to a new report (in pdf format) by the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. In Latino neighborhoods such as Washington Heights and Bushwick, residents are spending most of their income on rent.

Seventy-three percent of nonimmigrant Latinos and 83 percent of immigrant Latinos rent their home, the highest percentage than other groups (For Blacks, 78 percent for nonimmigrants, 75 percent for immigrants, and, for whites, 53 percent for nonimmigrants, 59 percent for immigrants), noted the study.

" This report equivocally shows that affordable housing should be one of the most important priorities for any elected official who cares about New York's Latino community," study author Carlos Vargas-Ramos told the Daily News.

Another recently released study by the National Housing Conference also found that immigrants are having trouble finding affordable housing. Study author Barbara Lipman used census data and housing survey to analyze immigrants's living condition and found that immigrants are likely to spend more than half of their income on housing.

" Obviously, it's an issue if you're paying half of you income on your housing; what do you have for anything else," she told Fresno Bee. Lipman's study also shows that low and middle income immigrants are six times as likely to live in overcrowded homes.

Last December, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced his plan to preserve 38,000 units of affordable housing, and build 27,000 more over the next five years. Bloomberg has said that he is committed to the plan despite the city's budget deficit.

MOVEMENT OF FOREIGN-BORN POPULATION

A new census report tracking the movement of foreign-born population from 1995 to 2000 found that New York state sent 205,000 more immigrants to other states than it received from them. Similar " gateway" states such as California and Illinois also lost their foreign born population to other states.

Some believe that immigrants are leaving the "gateway" states for the same reasons natives do: to find affordable housing and a better standard of living.

" It's a middle-class flight motivated by cost and congestion," demographer William Frey told USA Today.

However, the same census report also shows that New York state had a constant supply of new immigrants, with 583,769 people who were born in another country entering the state in the same five-year period.

In New York City alone, foreign born population accounts for 36 percent of the city's 8 million total population, according to 2000 Census.

IMMIGRANTS AND WAGES

A new study by University of California researcher Liza Catanzarite shows that newly arrived Hispanic immigrant workers drove down wages in working class and service jobs.

By analyzing 1990 Census data of male workers in 38 US metropolitan areas, including New York City, Catanzarite found that both native people born and immigrants earned on the average 11 percent less than others in comparable fields when they worked along side newly arrived Hispanic males.

" These findings push us to understand that wage penalties in 'brown collar' occupations stem from newcomer Latinos' marginal status, and not from immigration per se," Catanzarite told the Associated Press.

The term "brown collar" refers to occupations where Latinos are over represented, mainly low-level service and manufacturing jobs, according to the study. Immigrant Latinos constitute as much as 40-71 percent of workers in many of these fields.

Catanzarite also noted that new Hispanic immigrants are unable to resist low wages and have little political power to demand higher pay. She suggested that better protections for immigrants will, in turn, help raise wages for all.

An immigrant from Bangkok, Thailand, Chaleampon Ritthichai is the editor of The Citizen.

High School Push Outs

When the New York State Education Department began the phase-in of stricter new graduation standards, educators feared that an increasing number of students would drop out of schools before they graduated.

In recent months, evidence has emerged that this nightmare is coming true – and that it is even worse than expected: some schools may be deliberately driving them out.

In the late 1990’s, the state began requiring that all students in New York pass five rigorous Regents exams in order to receive a high school diploma. At that time, fewer than one in five New York City students met that requirement. Since then, new state and federal accountability policies have further ratcheted up the pressure on students, educators, and school officials by adding penalties for schools and districts whose students do not pass these and other required tests at acceptable rates.

Dropout numbers have been gradually edging up since the new graduation standards were implemented. But there is another disturbing trend, according to a recent New York Times investigation, as well as a studyreleased last winter. Drop-out rates may dramatically underestimate the number of New York City high school who leave the public schools without graduating.

According to these reports, New York City Department of Education data show tens of thousands of students who leave the high schools categorized as "discharged." This category includes students who transfer to other schools or school systems or who go to private schools; it also includes students who move from regular high school programs into alternative programs -- programs that lead a General Educational Development diploma (GED) rather than to the much more marketable regular high school diploma.

The reports allege that many low achieving high school students, unaware of their legal right to stay in a regular high school until they are 21 years old, are being counseled or forced into high school equivalency programs. More and younger students than ever are being encouraged to join these programs, though the GED is a less valuable degree than the regular high school diploma, and though most of the students who leave high school with the intention of enrolling in one of these programs either never join or never receive the certificate.

Students who do not complete these alternative programs may not be counted as dropouts in Department of Education statistics. Advocates believe that the official dropout rate of 20 percent would climb to 25 or 30 percent if these students' outcomes were included.

Chancellor Joel Klein has acknowledged this "tragedy" and the need to create more programs for students who need more time to graduate. The Times quoted Klein as saying, "The goal is for students to graduate in four years, but we've got to stop giving the signal that we're giving up on students who don't do that."

Now that the Department of Education has acknowledged the problem, advocates recommend specific steps to remedy it, including analyzing discharged students data to learn more about the students affected and creating state and city policies explicitly discouraging the practice of pushing out at-risk students. Advocates for Children of New York has also filed suit against the Department of Education charging that Franklin K. Lane High School in Brooklyn illegally discharged hundreds of students over the past three years.

New High School Bill Introduced in the U.S. Senate

The No Child Left Behind Act may add to the Department of Education's pressure to shunt aside low performing high schoolers. Under the federal education law, high schools receive "credit" only for students who graduate on time with a regular diploma. Schools thus get no incentive to keep students in school for a fifth or sixth year in order to help them graduate, though, in New York City, an additional 10 percent of students are able to graduate after a fifth year.

New York City is not alone in its need to address these problems. Democratic Senator Patty Murray of Washington recently introduced new legislation to help reform the nation's secondary schools, citing a need to reach older students largely left out of No Child Left Behind. The Pathways for All Children to Succeed (PASS) Act seeks to provide extra support for high school students through a focus on adolescent literacy, counseling, and a grant program to improve student achievement in low-performing high schools.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and Director of Policy Development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a not-for-profit coalition working to reform New York State's education finance system to ensure adequate resources and the opportunity for a sound basic education for all students in New York City. The views expressed are her own.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and Director of Policy Development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a not-for-profit coalition working to reform New York State's education finance system to ensure adequate resources and the opportunity for a sound basic education for all students in New York City. The views expressed are her own.

School Lunch Lack; Fixing Diesel-Fueled School Buses

One recent summer morning two different groups held back-to-back news conferences at City Hall on issues related to children – one about lunches (or the lack of them) during summer school, and the other about air-quality standards (or the lack of them) for diesel-fueled school buses.

Summer Meals

The Coalition To Take Back Our Schools supporting community groups were at City Hall to protest the decision by the Department of Education to cut breakfast and lunch programs from summer schools with fewer than 200 students in attendance. These meals, part of the summer food service program, are federally funded and designed not only to feed children in mandatory summer school programs but also low-income children in the vicinity of the schools whose families cannot afford to feed them.

Posters and brochures encouraging families to bring children to local schools for FREE breakfast and lunch were widely circulated on subways, buses, and in food stamp offices. Many parents of students attending summer school found out only after putting them on the school bus for the first day of summer school that their children would not be provided with the meals.

"It’s false advertising," said Carmen Santana, one of the organizers of the rally from the Coalition to Take Back Our Schools. Santana’s own children are attending a summer program in Queens where the meals were eliminated without notifying parents.

In the past, the cutoff for serving meals in the summer program was for schools with 100 or fewer children. As a result of the minimum being raised to 200 students, 44 elementary and middle schools, and 26 high schools, were not serving breakfast or lunch, affecting about 10,000 children, according to Santana. (An official from the Department of Education was not able to confirm the number of children affected, but disputed that it was that many.)

Milda Romalez, a member of the community group Make the Road by Walking, spoke softly in Spanish through an interpreter about her reasons for being present at the rally: "I represent the parents of the children of Bushwick, Brooklyn. So many parents cannot afford feeding their children before school. If they are not fed in summer school, they go hungry. How can children learn on an empty stomach?"

Funds for the Summer Food Service Program are paid for by the federal government and schools are reimbursed, per child, per meal, with higher reimbursements in the summer than during the school year.

"The summer food service program is a win-win situation for children and the city," said Deena Kolbert of Community Food Resource Center. "Families don’t have to fill out forms, there are no application procedures. People are hired to serve the meals at the schools over the summer so it provides jobs to the community; it’s win-win."

But the Department of Education didn’t see it this way. Reportedly, it wasn’t economically viable to operate cafeterias and staff them to service small numbers of children. Even though funds are eventually reimbursed, the Department of Education must lay out the money first and, in this economic climate, even meals for children are no longer sacred.

"Denying these children free lunch is a violation of their rights," explained Elizabeth Sullivan from the Center for Economic and Social Rights, an international human rights organization. "It violates the right of students to a quality education (they are not receiving the food they need to learn), the right of parents and community members to participate in decision making regarding that education (they were not notified or consulted about the decision), and the right to food."

According to Paul Rose, a spokesperson for the Department of Education, "at no time were students deprived of the opportunity to enjoy a school meal." Children from the cutoff schools were just required to walk or take public transportation to schools that did offer breakfast and lunch. But families, uncomfortable with having their kids traveling a half mile away for meals, found this plan unsatisfactory.

In response to parent feedback, three weeks into the summer program, and a few days after the rally, the Department of Education did begin delivering meals to the schools that had their kitchens shut down: cereal, milk, orange juice, and a blueberry muffin for breakfast; a slice of cheese on a roll with lettuce and tomato, three-bean salad, a fruit, and milk for lunch.

"I’m very happy we were successful in getting something for these kids," said Carmen Santana. "A lot of these children are the neediest in the city."

Protecting Kids from Diesel Emissions on School Buses

State Senator David A. Paterson assembled a press conference at City Hall in July to announce his intention to introduce legislation to protect kids from the dangerous diesel fumes on school buses. "There are over 5,000 school buses transporting our children back and forth to school in the city," said Paterson. "My children ride on them. And we now know that the air quality inside these buses is worse than the air quality outside. With the skyrocketing rates of asthma, this puts the health of these students in jeopardy."

Paterson distributed copies of "No Breathing in the Aisles," a report conducted by the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Clean Air Coalition, and the University of California at Berkeley, that monitored the air on diesel-fueled school buses in California and found levels on the buses to be four times greater than in the air outside the bus, and up to 46 times higher than the Environmental Protection Agency’s cancer risk level. Many of these same types of school buses, without pollution control devices, are on the road in New York, spewing diesel particulate matter into the buses, the majority of which are fine particles, especially harmful to children.

Paterson expressed sympathy for the hardships private bus companies face in finding the resources to retrofit their buses with filters and switch to low sulfur diesel fuel. He also spoke encouragingly about negotiations currently taking place between bus operators and the New York Power Authority who offered last year to retrofit 1000 city school buses with diesel particulate filters which would reduce emissions significantly.

But despite his sympathies, Paterson was issuing an ultimatum: School bus companies must retrofit their engines and purchase lower quality of sulfur fuel. “If that is not the case, we don’t want any of our young people on their buses."

The state bill would mandate that buses transporting New York City school children must be retrofitted with either diesel particulate filters which, combined with a switch to using ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel, would reduce emissions by 90 percent, or diesel oxidation catalysts which would reduce emissions on older buses by up to 30 percent.

"I understand that there are costs involved for the bus companies," said Senator Paterson, "but the costs to treat children with asthma are higher than costs to retrofit."

Paterson was joined by Councilmember David Yassky from Brooklyn, who said he was going to introduce legislation through the City Council in support of Paterson’s bill. "One in ten New York City school kids has asthma" said Yassky. (That number is one in four in Harlem) "When you put a child with asthma on one of these buses, it can pose a serious health risk. We must have these retrofits with low sulfur diesel fuel by September. If it is not in place by September, it will be a shameful thing."

"There is no reason why New York City school children have to breathe so much diesel soot, given that cleaner fuels and engines are available," said Rich Kassel, Senior Attorney from the Natural Resources Defense Council, who also took the podium in support of Senator Paterson’s bill.

"It’s a really simple issue," explained Kassel. "Diesel exhaust triggers asthma attacks, cancer, and premature death. But the problem can be fixed by doing four things:

(1) retire the oldest, dirtiest buses;

(2) replace them with the cleanest available bus fuels and technologies;

(3) retrofit remaining diesel buses using low sulfur diesel fuel and particulate matter filters or traps;

(4) reduce idling of all buses so kids aren’t exposed while waiting to board the bus."

The issue of idling was also underscored by Rebecca Kalin, director and founder of the Asthma Free School Zone. "Until we get through this quagmire," said Kalin, "there is only one solution and that is to make asthma free zones around our schools where idling is not permitted.

"There is currently a NO IDLING law on the books, said Kalin, "but it is routinely ignored." In fact, in a Yale study on school bus emissions, levels of fine particulate matter were very high inside an idling bus that was loading and unloading students, and highest when the bus was idling with the windows open, particularly if more than one school bus was lined up, allowing exhaust from one bus to enter another.

Attempts were made to speak with school bus company representatives, but they were not available at press time. We were informed a few weeks ago, however, that the delays in retrofitting New York City school buses have nothing to do with cost but instead have to do with a failure of the exhaust systems to meet the required temperatures on the buses tested.

Recently, the New York Association for Pupil Transportation, a New York State school bus organization that does not include New York City bus companies, announced that they would voluntarily retrofit at least 5,000 school buses a year over the next three years. This agreement between the Environmental Protection Agency and New York Association for Pupil Transportation is part of the EPA's Clean School Bus USA program and also includes a pledge from the bus association to reduce idling by at least 50 percent. These initiatives will affect approximately 2.3 million school children.

Unfortunately, none of them in New York City. The state agreement is "an important first step in ramping up voluntary commitments for dirty yellow school buses to clean up their act," said Kizzy

Charles-Guzmán from the West Harlem Environmental Action, Inc. But now, suggests Charles-Guzmán, the Department of Education needs to "stop signing contracts with school bus fleets that refuse to provide clean and safe transportation for our children."

"It is our children suffering from these respiratory diseases," said L. Ann Rocker from the North River Community Environmental Review Board, Inc. "It’s not right for us to be continually forgotten."

Lynda Crawford wrote the social services topic page for Gotham Gazette, and has written for City Limits, New York Woman, The New York Observer, and The New York Daily News.