Educating All New Yorkers at CUNY

|

Related: |

As New York’s public university — and the largest urban university in the country — the City University of New York has long been at the center of political battles over the role of a public university in a diverse metropolis.

Since 1847, when it was formed as the Free Academy, CUNY has sought to provide an affordable education to New Yorkers. Back then, the targeted audience was small – male graduates of city public schools – but as it grew, the school began gearing its mission to immigrants and offering practical training for jobs, providing evening courses, and helping to train World War II veterans.

Over the years, the government’s vision of how CUNY could best serve the city reflected changes in the political climate. For more than a century, the university was free – for much of that time it even provided books – but admission was limited. “You always had to be a good student, but it didn’t become tremendously competitive, as I see it, until the 1960s when you had to have a grade point average in the 90s to gain admission to the school of your first choice, ” said Sandra Roff, a professor at Baruch and one of the authors of “From the Free Academy to CUNY: Illustrating Public Education in New York City 1847 to 1997” .

That changed in the 1970s. Mounting political pressure and demands for equality by black and Latino New Yorkers spurred the university to guarantee admission to every New York City high school graduate. A few years later, faced by the fiscal crisis and by opposition to free tuition from political conservatives, the university began charging tuition. It also had to prune its budget -- cutting back on full-time teaching positions and spending on facilities.

The conventional wisdom has it that, by the 1990s, this had wreaked havoc. Mayor Rudolph Giuliani assailed the lack of standards at the university. In 1999, Benno Schmidt chaired a panel that called CUNY “an institution adrift.”

“A third of the campus presidencies were vacant and they couldn’t fill them,” said Neil Kleiman of the Center for an Urban Future. “No one would take the job. Nationally, CUNY was seen as the worse place you could go.”

Since then, the university ended remedial classes at the 11 four-year colleges, requiring the students needing them to take such classes at the six community colleges or elsewhere. A new chancellor – Matthew Goldstein – came in. He began restoring full-time faculty positions and issued a master plan . Students must pass a test – the CUNY Proficiency Exam – before they can move on to a third year at a senior college or graduate from a two-year school.

Many hail the results. Earlier this year, five years after he lambasted CUNY, Schmidt, now chair of the university’s board of trustees, called CUNY “the pride of the city.”

“The progress made by CUNY in the last five years has been stunning. I know of no comparable gains in such a short time in any public university system in the United States,” he said.

The university says that the SAT scores of incoming freshmen have risen and more students from the city’s best high school now view CUNY as a viable option.

While not disputing the university’s stature today, some say things were never as bad as Giuliani and other CUNY critics said they were. “Of course you can always have improvement,” said Councilmember Charles Barron, chair of the council's higher education committee, but the charges that the university was bad are “bogus...I think we’ve always had a quality degree.”

Others such as Dorothy Lang, an associate professor of business at the College of Staten Island and chair of the CUNY Association of Scholars, sees progress but says standards for four-year colleges could be higher still. She says that she has had students who did not have the background needed for her classes. For example, one young woman from Asia taking a management course was baffled by a problem involving driving a Chevy to Sears. She was simply unfamiliar with Chevys or Sears.

But some say that, if it is to fulfill its mission to the city, CUNY has an obligation to students like that. The faculty union, the Professional Staff Congress, has opposed the end of remedial classes at four-year school. “We are all for top quality education,” said union president Barbara Bowen, but, she added, “there is a reason for having an urban university, and the primary one is to serve that diverse population.”

Tuition increases may also keep some potential students away, although so far there is little evidence of this. Full-time students now pay $4,000 a year.

If student aid was cut, that could take its toll. With that in mind, Barron plans to mount a drive to restore free tuition. “When CUNY was white, it was free, “ he said, adding, “if CUNY could afford free tuition during the Great Depression it should certainly be able to today.”

Â

School Funding and the Special Masters

When New York City's public schools reopened this month, hundreds of thousands of its nearly 1.1 million students returned to overcrowded, poorly equipped schools with inexperienced teachers and outdated textbooks. Because the state legislature and Governor George Pataki failed to act on a court order to overhaul the state's school funding system, many schools will face another year without necessary resources like libraries, laboratories, and gymnasiums, to meet their students' basic needs. In violation of their students' constitutional rights, the city's strapped-for-cash schools will have to make due without billions of dollars in additional funding to which they are entitled.

Last summer, the state's highest court ruled in the case of Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. State of New York that the governor and the legislature must fix the state's flawed school-funding system. The court held that Albany's funding system shortchanged New York City schools to the point of creating system-wide failure, and it ordered the state's political leaders to change it. The governor and the legislature were given a year to ensure the city's schools sufficient funding for quality teachers, reasonable class sizes, and adequate facilities and classrooms.

But elected officials chose to disobey the law and let the court's July 30, 2004, deadline pass without agreeing on a solution; they will now let the court find a remedy for the city's school children.

Justice Leland DeGrasse of the State Supreme Court in Manhattan, who has jurisdiction over the case, said last year he would "hit the ground running" if the July deadline passed without acceptable action on the part of the state. Just four days after the deadline, the judge made good on his word. He appointed a panel of three "special masters" -- referees who will make recommendations to the court about how best to fix the state aid system so that all schools get the funds they need. The distinguished jurists include two former appellate judges and a former Fordham University Law School dean. They will have until November 30, 2004, to submit their report to the judge, who will then rule on what is to be done.

The referees' charge is to determine whether the state has complied with the court mandate -- though lawyers for the state have already admitted it did not -- and then help Justice DeGrasse shape a suitable plan. If the actions of referees in other states are any indication of what lies ahead, the panel may: *recommend a specific dollar amount owed to New York City; *mandate new accountability measures or changes to the funding formula; *or even, although unlikely, shut down schools until legislative action occurs.

Justice DeGrasse indicated that, although the court does not make policy, it does have a duty to protect students' constitutional rights. Demonstrating his commitment to enforcing reform, he specifically asked the panel to pay special heed to issues of class-size reduction and teacher quality.

THREE HEARINGS SO FAR

So far, the referees have held three hearings with both sides in the case - Governor George Pataki, and the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, the coalition (where we both work) that brought the lawsuit over 11 years ago.

Pressed for time, the panel quickly asked each side to present their proposals for providing schools the funding to which they are entitled. In written briefs and later oral presentations, the parties specified dollar amounts, based on analyses from outside experts, and outlined accountability reforms. The referees also received three additional proposals, one each from the state assembly, the state senate, and the city.

All five proposals agree that about $4.3 billion to $5.6 billion more is needed each year for the city's schools but spending should be ramped up over a four- to seven-year period. Eighteen other organizations, including the Board of Regents of the State of New York and the United Federation of Teachers, will participate as amici curiae, or friends of the court, and will submit their own briefs this month.

At the latest hearing on September 15, each side had the chance to air any grievances they had with the other's approaches. The city of New York, although not a party in the case, was also allowed to participate. They asked the referees for more of a say in deciding the kind of reforms that may result from the panel's proceedings, since at the end of the day they are responsible for running the city's school system.

During the hearing, lawyers for the city asked for about $5 billion more in new money, highlighted the importance of tying accountability reform to any funding recommendations, and stressed the mismatch between qualified teachers and needy schools. They asked the panel to take up this last issue but encountered a less than eager reaction. Judge William C. Thompson, one of the special masters, advised, "if we give you the money, [it's your job] to fix it."

To each side's credit, the issue of how much additional money is needed is probably the most resolvable at this stage. The three sides revealed similar figures, and negotiations on accountability reform are also well under way. If settled, these agreements could help yield actual reform.

WHAT IS THE POWER OF THE SPECIAL MASTERS?

A major sticking point persists: What sort of recommendations can the special masters make and what influence can they have?

The state believes the special masters should simply grade the governor's attempts at compliance, like a teacher would a term paper, and should he flunk, "go back to the drawing board." The panel should not, said the state's lawyers, act as another legislature and direct the state to make specific repairs.

But the Campaign for Fiscal Equity argued that the panel must do more than give Governor Pataki a failing grade for noncompliance. They cited precedents in other states and asked the special masters to recommend a specific plan that averts even more delinquency from the governor and the legislature.

In a related dispute, the sides differed on how (or even if) the panel should address the question of who funds the increase; is it the state, the city, or the federal government? To tackle this question, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity proposed a detailed formula that would provide a transparent and simplified way for determining at what level of government the money should come from. The formula addresses the difficult and highly political question of what percentage of the increase should be borne by the state and what percentage should be borne by the city. But the state maintains that it is the job of the legislature to decide who should foot the bill, not the governor, and certainly not the court.

However, as the Campaign sees it, the failure of the assembly, the senate, and the governor to reach any consensus in their summer deliberations on school funding is a clear indication of what is likely to happen if the governor passes the buck, literally, on this issue. It is feared that putting this important issue in the legislature's hands may trigger another logjam in Albany-and it is the city's kids who will, in the end, pay the price. As Justice Leo Milonas, one of the special masters, forewarned during this discussion, "The governor and legislature don't bother to do their job."

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and the director of policy development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, where Stacy Feldman also works, as a public engagement associate.

Connecting Education and Voting

|

The Youth VoteEfforts to get out the youth vote this year range from the perennial Rock the Vote campaign, to MTV’s Choose or Lose 2004, to hip-hop icon Sean Combs’ new Vote or Die! effort, which aims, in Combs’ words, “To make voting cool.”Not to be outdone by P. Diddy and Christina Aguilera, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the New York City Council recently passed a law requiring public high schools supply each graduating senior with a voter registration form – in an effort to get New York youth to vote. But how will they respond? Here are a variety of responses from young people hanging out at Union Square, a place of great political history. “After the last [Presidential] election, many of my friends realized there’s no real reason to vote,” said Chris Ramos, a recent high school graduate. “It doesn’t count.” “Not a lot of my friends vote,” said Javacia Finney, 21. “They don’t care about politics, like a lot of young people they’re not informed.” “I don’t understand not voting,” said Zach Shapiro, 17. “Most kids actually do care about the issues. It’s more laziness than anything.” “If I have the privilege of doing something powerful like that, I’ll take advantage of it,” said 17-year-old Victoria Santagato. -Josh Nathan Kazis |

Despite massive efforts by politicians, musicians, and celebrities to encourage young people to vote, it is clear that our youth are not being reached.

Only 180,000 of the 800,000 eligible New York City voters between 18 and 25 years old have registered to vote. Merely registering, however, is no guarantee that they will go to the polls. In 2002, only 32,000 registered young voters actually went to the polls.

Clearly, something else is needed to encourage their civic participation.

That is why I co-sponsored a new law requiring the Department of Education to provide graduating high school seniors with voter registration forms along with their diplomas. The legislation, known as the Young Adult Voter Registration Act, will reach young New Yorkers at a critical time in their lives, when we celebrate their accomplishments and send them out to do good in the world.

Like motherhood and apple pie, it’s hard to criticize voter registration efforts. Yet, the Young Adult Voter Registration Act has been dismissed by some as pointless, “feel good” legislation that will ultimately be ineffective. It’s none of these things.

This legislation can help create a special connection between education and democracy. An informed electorate is the key to democracy, and voting is an essential lesson of civics classes. Why not give students a smooth transition to practice what they’ve studied; a chance to put what they’ve learned into action?

Young people, often inclined toward apathy about the political process, should be made to feel that voting is a natural culmination of their studies and part of their transformation into adults. Teaching them that “every vote counts” has more impact if we accompany the lesson with both the chance to fill out the appropriate paperwork, and an expectation that they will do it.

For these reasons, the Department of Education is in a unique position to bring young adults a step closer to the voting booth. Although Motor/Voter laws, which allow people to register to vote when they get their driver’s license, have increased voter registration in recent years, waiting in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles hardly creates a lasting impression of civic duty. Graduating from high school, on the other hand, is an event that is not soon forgotten.

To be handed a voter registration form at this crucial moment, along with a diploma, tells young adults that society values those two pieces of paper. It connects voter registration with adulthood, personal achievement and success; registration becomes a rite of passage, instead of a chore. It says that voting is a hard-earned reward and the ticket to a better future, much like a diploma. In combination with civics classes, this is the perfect opportunity to realize the values of democracy in our city.

Eva Moskowitz represents the Upper East Side of Manhattan and chairs the education committee in the New York City Council.

Resources and Efforts for Youth Voting:

Arsalyn

Black Youth Vote

Campus Compact

Circle Youth

Citizen Change

Declare Yourself

Freedom’s Answer

Kids Voting USA

MTV’s Choose or Lose

November 2nd

Rock the Vote

Teen Politics

Teen Vote USA

Youth Vote Coalition

Vote or Die

Cloning A Charter School From Connecticut

As part of his plan to open 50 charter schools in New York City over the next five years, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has invited a successful Connecticut charter school to clone itself here.

On its face, the plan seems sound. Many parents in this city would welcome the chance to send their children to a school like Amistad Academy, a small New Haven middle school, where nearly all students are black or Hispanic. Chosen by random lottery, most entering students are struggling readers. By eighth grade, they're winning prep-school scholarships and outperforming white suburban kids on standardized tests.

Even the usually skeptical New Haven Advocate, the city's alternative newspaper, dubbed Amistad "a school that works." A glowing report in that paper described orderly rows of kids in crisp uniforms discussing Hamlet with a passionate teacher. School begins at 7:30 and ends at 5. Parents contractually agree to unplug the TV and oversee homework.

Bolstered by $1 million in private donations and Mayor Bloomberg's cheerleading, Amistad leaders plan to open three schools here in the fall of 2005 and two more the following year

Good news for New York? Possibly. Anyone who's seen "All About Eve" knows that New Haven used to be Broadway's barometer: shows that survived out-of-town tryouts there often thrived here.

But not every production survived the transition to the big stage, and in Amistad Academy's case, we're talking about a production of Lilliputian proportions.

Test score results at Amistad Academy are based on low numbers. The school opened in 1999 with 84 students in fifth and sixth grades. Even after adding Grades 7 and 8, enrollment last year totaled just 250.

In the Connecticut education department's strategic school profile for Amistad for 2001-2002, [In PDF Format] the most recent available, Amistad reported academic strides made by its eighth graders. Most had entered in sixth grade with below-par scores in writing and math on standardized state tests. Two years later, all but four kids ranked at "proficiency" or "mastery" level.

Impressive to be sure, but since the entire 8th grade class totaled 32 students, the four lagging behind grade level comprised 12.5 percent of the class.

And can New York replicate Amistad Academy's small class sizes? In most New Haven public schools, most middle school classes have 27 or 28 students. In New York, where middle school class rosters routinely exceed 30, many parents would be thrilled with that.

Yet Amistad Academy's classes are even smaller. According to a report filed by the school for the 2000-01 school year, seventh-grade classes at that time averaged 13.1 students. Pat Lucan, president of the New Haven Federation of Teachers, noted that unionized New Haven teachers could probably achieve the same results as Amistad's non-union staff with similarly sized classes.

How does Amistad Academy afford its teacher-student ratio? Like other charter schools, Amistad depends on private donations to supplement state funding. Its founder and executive director, Dacia Toll, a Yale Law School graduate, is widely respected and, according to many in New Haven, well connected. The school's New York debut already has financial backers who will want to see it succeed here.

According to teachers' union president Lucan, Amistad also benefits from the unpaid labor donated by its non-union teachers, who work longer hours than the typical New Haven school day. While praising the school, Lucan said, "Many of us have economic concerns that don't permit us to do what, altruistically, we would like to do."

It's a safe bet that Mayor Bloomberg finds Amistad Academy's non-union status at least as attractive as its test scores. "Teachers in charter schools are typically non-union. That's supposed to be part of their appeal," said Ron Davis, a spokesman for the United Federation of Teachers, which represents the city public school teachers.

How ironic that Mayor Bloomberg, after wresting control of the city's schools, now promotes charter schools, which operate outside Department of Education control and are accountable only to the state.

Amistad Academy is to be commended for its accomplishments. But does New York really need to outsource educational talent? Already here, under the mayor's control are schools with Amistad Academy's potential. They, too, have raised the scores of low-income, minority students.

Even more amazing, they have accomplished this with overcrowded classrooms, inadequate textbooks, antiquated labs - and unionized teachers.

At M.S. 61 in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, nearly 1,400 students are crammed into a drab building. Most are low-income black students with roots in the Caribbean; several bilingual classes are taught partly in Haitian Creole.

This middle school has its share of problems. In fact, it appears on a list of hard-to-staff schools, to which the city tries to lure teachers with the promise of tuition reimbursement dollars called "Teacher of Tomorrow" scholarships, but known informally as "combat pay."

Yet something remarkable is going on at M.S. 61. Several years ago, dedicated teachers and administrators established a rigorous academic program at this Brooklyn middle school. It's named the Britou-Moore Academy, after two students who tragically died on a college-sponsored trip; one perished trying to save the other.

Unlike the Connecticut academy, which admits students by open lottery, M.S. 61's scholar's program has some selection criteria. But it is not strictly an honors program. As at the New Haven school, only hard-working students with dedicated parents even cast in their lots. Sixth graders are accepted on the basis of standardized test results. But other M.S. 61 students can transfer to the program in seventh and eighth grade if they're prepared to do the work, regardless of their scores.

Because the school hesitates to turn students away - unlike charter schools with limited lottery slots -- the seventh- and eighth-grade classes in the Britou-Moore program are packed. Yet students flourish. As at Amistad, Britou-Moore students wear uniforms. Uniforms are not unusual in New York City public schools. And, as at Amistad, minority students are held to high expectations.

Like many other unionized teachers in New York, Britou-Moore teachers often donate hours of their own time to the students. And the staff of this Brooklyn program does not judge progress solely by scores on citywide and statewide tests. Students willing to take on the workload can enroll in Regents courses in math and science. As a result, many graduate from middle school with some high-school credits already under their belts.

This year, 19 students from M.S. 61 went to the selective summer programs run by Johns Hopkins University's Center for Talented Youth. They qualified by scoring well on the S.A.T.s. That's right: they took the college boards while still in middle school.

Interestingly, several students at M.S. 61 made the Johns Hopkins cut on the college boards despite scoring at Level 2, supposedly below grade level, on statewide eighth grade exams. That raises questions about the validity of standardized test scores, and about schools like Amistad, where administrators have proposed tying teacher evaluations to the performance of students on Connecticut's tests.

It wasn't easy for the cramped middle school in Crown Heights to prep middle-school kids for the college boards. For one thing, they had to raise money for the test fees. And even in the Britou-Moore program, M.S. 61 students sometimes have to share textbooks. Some of the school's classrooms lack enough desks to seat students..

Instead of bringing in productions from elsewhere, perhaps the mayor should focus on the standing-room-only show right under his nose.

Also, though the Amistad Academy's name trades on a noble moment in New Haven's past -- the trial and acquittal there of Africans who had taken control of the Amistad slave ship - the school's non-union status is reminiscent of a sadder chapter in Connecticut history: the jailing of teachers in the 1970s for breaking laws then prohibiting them from collective bargaining.

Marcia Biederman writes about city public schools for InsideSchools.org and contributes regularly to The New York Times.

Urban Issues: Education

• Higher Education

• No Child Left Behind

• Vouchers

• • • • • • •

George W. Bush

Bush’s proposed 2005 budget includes increased funding for the Pell Grant program, which supplies grants to needy undergraduate students. Bush also proposes a public/private partnership that will provide $100 million in grants to a total of 20,000 low-income students who study math or science. Also supports new funding for education and job training programs. (Learn more)

Bush supports taxpayer-financed vouchers for private schools.

In 2001, Bush signed the No Child Left Behind Act into law, which requires standards of academic achievement. Schools that do not perform are placed on a "schools in need of improvement" list and students are entitled to transfer to a better school. If a school appears on the list for two years, low-income students are entitled to free tutoring services. (Learn more) Mayor Michael Bloomberg estimated that New York City would need $400 million a year in order to meet the requirements of the program, but the city has received far less.

John Kerry

Kerry proposes several programs to help pay for college. His Ready for College program would triple the tax credit to $4,000 for college tuition. He also supports a program that would provide full college tuition in exchange for two years of community service. (Learn more)

Kerry would reform the No Child Left Behind program by revising the standards by which the program is administered. For example, measures like graduation rates, teacher attendance, and student attendance would be more important than test scores in assessing how a school is doing. Kerry would also form a National Education Trust Fund that would help guarantee funding to meet educational obligations, including No Child Left Behind. (Learn more)

Kerry opposes vouchers for private schools. (Learn more)

• • • • • • •

Back to Urban Issues Main Page

• • • • • • •

GOTHAM GAZETTE’S RELATED ARTICLES

• Higher Education, Lower Budget

• No Child Left Behind

• No Child Left Behind and New York City

• School Vouchers

School Trips Go Commercial

In the final weeks of the school year, nobody feels like working hard. That could be why lawmakers in Albany left for vacation without agreeing on a way to provide a "sound, basic education" to New York City's schoolchildren by July 30, as a court has ordered.

While state leaders failed to agree on a politically palatable school financing plan that would aid not-so-needy upstate and suburban school districts as well as New York City, some city schools found their own ingenious solution to funding woes.

With the blessing of the city Department of Education, more than 50 city public schools this past school year took field trips to Petco and Sports Authority stores to hear employees speak on such topics as animal habitats and the importance of exercise. A number of these schools visited the stores repeatedly, taking different groups each time.

Just last month, as lawmakers wrangled over ways to take educational spending meant for New York City and spread it over the state, 13 groups of city elementary and middle school students visited Petco stores in Manhattan, Staten Island and Queens. In Manhattan alone, four Petco outlets played host to 68 school groups this past year. Most were from the public schools, according to the San Diego-based company.

Why would New York teachers take a class to Petco rather than a museum or a zoo?

"Schools with bigger budgets might visit a zoo or an art museum. For a school with no budget, a trip to Petco costs nothing except for transportation," said Shawn Underwood, a Petco spokesman.

That is less of an advantage here than in other cities, but an advantage all the same. To be sure, New York City school groups get free admission to the Bronx Zoo, But the New York Aquarium in Brooklyn charges $5.25 per child. Even the Central Park, Queens and Prospect Park zoos charge school groups $1 per child.

Moreover, free admission to the Bronx Zoo means a teacher-led tour with no frills: areas like the Butterfly Zone and Children's Zoo cost extra. At Petco, store staff rolls out the red carpet. Kids can pet birds, handle reptiles and take home a goody bag crammed with Petco tatoos and frisbies.

The trips are the brainchild of an educationally savvy Chicago marketer, Susan Singer, who arranges them through her Web site, complete with lesson plans said to fulfill national learning standards.

Singer said she's been working with New York City schools for more than three years. Lately, she said, momentum has been building, and a new learning destination for the city's public schoolchildren will debut in fall: Waldbaum food stores.

Elsewhere in the nation, critics have questioned the educational value of such expeditions and deplored their commercialism. In April, a Buffalo Public Schools spokesman told the Buffalo News that approval of such jaunts would be unlikely there except for students studying business.

The New York City Department of Education has no such compunctions.

When asked about the Petco and Sports Authority expedition, the department issued this statement: "School trips should have an educational focus and be viewed as an extension of the curriculum and learning environment. The fact that there may be a tangential commercial component of a trip would not require that it be banned."

Indeed, an assistant principal at an elementary school in Queens, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the education department was encouraging schools to take the trips to Petco and Sports Authority.

Could the "Furs, Fins and Feathers" trip to Petco - its name on the Field Trip Factory Web site - be the city's solution for schools with no science labs? In many middle schools, eighth graders must prepare for the standardized state exam in science by sharing microscopes. Often water needed for experiments comes from the drinking fountain down the hall.

That might explain why the city's scarce supply of school buses are apparently used as conveyances to Petco. Jennifer Escobar, the operations manager of the Union Square Petco store, said some public schools pull up to her store in yellow buses - often hard for schools to secure for trips to museums and concerts.

The New York City Department of Education, which used a shady bidding process to give Snapple exclusive rights to sell its products in schools, can't be expected to have the compunctions of Buffalo's school district.

With the Field Trip Factory set to add Waldbaum's tours to its destination list - Singer said eight New York schools have already gone out-of-state for her company's supermarket trips, which focus on nutrition - city museums and zoos may find it hard to compete.

Not only are the trips free, but arrangements are streamlined. "We try to make it seamless," Singer said. Contrast that with the school group rules at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Groups from New York City schools get into the Met for free, but the museum's Web site carries stern warnings about chaperoning requirements, limits on the number of visits per school, and a minimum 12-week wait for reservations.

The Queens County Farm Museum also offers opportunities for city kids to pet animals and learn about their needs. The museum's executive director, Amy Fischetti, said her nonprofit facility could not survive without charging school groups admission fees, ranging from $2 to $8, depending on the program. She declined to comment on the Petco tours. However, she did say, "We'd rather see the schools coming to us."

Marcia Biederman writes about city public schools for InsideSchools.org and contributes regularly to The New York Times.

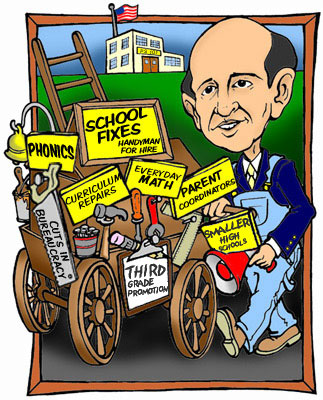

School Reforms

|

|

After years of volunteering in her school in Astoria, Anita O'Brien now gets paid to be a school activist. As one of the 1,200 new parent coordinators, parents approach her at school, at meetings and in the neighborhood -- hungry for information and guidance. "They feel very comfortable coming up to me and asking me questions and I always try to get them an answer," the mother of three says.

But for all their efforts, O'Brien and the others do not always have the information. After a year of major changes in New York City schools, many questions remain unanswered.

The biggest one for most New Yorkers: Has the Children First Initiative – which brought the virtual elimination of community school districts, personnel changes, the introduction of a standardized curriculum and a new third grade promotion policy - improved New York's schools?

"Not to sugarcoat this [but] I think that it was by and large an extraordinary year for us," Schools Chancellor Joel Klein said in an interview. "We've executed well -- not perfectly, but well -- and I think we're positioning the system for the long-term transformational change."

"If reading and math scores aren't significantly better, I will look in the mirror and say I've failed," Mayor Michael Bloomberg was quoted as saying when he won control of the school system two years ago. "And I've never failed at anything in my life."

And so far, the mayor sees success here as well. At a press conference last week to trumpet improvements in school safety, he offered a generally upbeat assessment of the year. "The fact of the matter is, we don't have broken windows and missing floor tiles," he said. "The fact of the matter is we do deliver the books on time. The fact of the matter is we have parent coordinators that in most cases are making a very big difference."

But others disagree. At a press conference in late June, Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum gave the chancellor a grade of C-, saying his "ambitions have not so far produced positive results." In particular, she faulted the mayor for not doing more to relieve crowding in classrooms and for not seeking advice from parents, teachers and principals.

The City Council, whose speaker Gifford Miller is likely to challenge Bloomberg next year, has been a persistent critic, taking on many of the individual reforms. For example, it has condemned the mayor's policy of holding back third graders who fail a standardized test, questioned the drive toward smaller high schools and criticized the department's capital budget.

The teachers union, which is locked in a contentious contract dispute with the city, has faulted Klein and his top assistants for ignoring the expertise of teachers and interfering too much in the classroom.

Here is some of what Bloomberg and Klein tried to do this year and how they fared.

- CURRICULUM

- TEST SCORES

- THIRD GRADE PROMOTION

- BREAKING UP HIGH SCHOOLS

- HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS

- REORGANIZATION

- THE TWEED CULTURE

CURRICULUM

Until September, New York had no uniform education program for its 1.1 million students. Individual community school districts -- and schools -- selected their programs, often changing them from year to year. This confused students and placed a particular burden on low-income youngsters who tend to switch schools more frequently than their more affluent classmates.

In 2003, Klein said that, except for some 200 high performing schools, all schools would adopt uniform curricula for reading and math.

Some educators -- notably the teachers union -- objected. Opponents grumbled that the Department of Education was dictating what teachers could hang on bulletin boards and how they must arrange the desks. Jill Levy, president of the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, which represents principals, said this was such extreme micromanaging that she termed it "nanomanaging."

"Not everyone learns at the same pace," said Jo Rossicone, outgoing principal of Brooklyn's IS 220, whose student body includes many English language learners. "They don't take into account language challenges." But despite that, Rossicone believes the uniform curricula are a good thing: "I see a focus. I see everyone on the same page," she said.

If liberal educators had their doubts about a uniform curriculum, conservatives objected to the specific programs selected. Bucking what Education Week has described as "a national penchant for a highly structured, skills based approach to reading and mathematics instruction," the Department of Education spurned phonics and math drills. The language curriculum does not stress letter sounds but instead employs popular children's books, literary discussions and writing. The math curriculum is similarly non-traditional.

This approach encountered flack from the U.S. Department of Education, which expressed doubt that the reading curriculum for the youngest students would enable the city to qualify for about $40 million in federal funds. In response, Klein adopted a more traditional commercial reading program for 49 of the city's lowest performing schools.

This did not mollify critics such as Sol Stern of the Manhattan Institute. "Many of the programs and methods now being crammed down teachers' throat have no record of success and are particularly ill-suited for disadvantaged minority children," Stern wrote in City Journal last fall.

School officials, of course, disagree. "We did not want to settle for anything but a rich and vigorous curriculum for our students" said Diana Lam, the deputy chancellor who selected the programs before being forced to resign in the nepotism scandal earlier this year.

THE TEST SCORES

Whatever the shortcomings of standardized tests, they have become a kind of shorthand for determining whether what is being done in the classroom works. This year's results produced a mixed verdict.

For the first time since the test was instituted six years ago, fourth grade reading tests scores fell in the city, as more than half the children tested failed to meet state standards. On the other hand, eighth grade scores improved, as did math scores for third, sixth and seventh graders.

While saying a single year's test scores "are not what this is about," Klein said, "It's a favorable picture." Scores rose on six of the tests given, he said, and fell on three.

The mayor's opponents saw things differently. Citing the fourth grade reading scores, Speaker Gifford Miller called upon the Department of Education to consider scrapping the new reading program. And, while math scores rose, opponents of the new curriculum attributed it more to test preparation than to the new approach to teaching mathematics.

THIRD GRADE PROMOTION

Parents, teachers and New York employers have long despaired at the number of students who leave the school system without basic skills. How could a student be promoted year after year and be unable to understand written material or do basic math?

To confront this, in January. Bloomberg announced that he would end what he called "social promotion" for third graders, leaving back children who received the lowest score - a level one out of a possible four -- on standardized reading and math tests.

As third graders crammed for the exams, many educators declared the policy put too much weight on a single test. Others said efforts should instead focus on improving education in lowest grades, by reducing class size. "They are taking no responsibility for how a kid can be in schools for four years and still not know how to read well," said John Beam, executive director of the National Center for Schools and Communities at Fordham University. Klein now says the schools will try to shift more resources to helping their youngest students next year.

The department allowed some exceptions to the policy, giving students a chance to attend summer school and try again, instituting an appeals process and exempting English language learners and special education students. But the opposition persisted until the day the Panel for Educational Policy, the largely toothless successor to the Board of Education, was set to vote on the plan. With his proposal facing defeat, the mayor arranged for the firing of three members of the panel, insuring that his third grade retention plan would be a reality.

And so more than 10,000 of the city's approximately 80,000 third graders now face summer school or repeating third grade -- up from 4,817 third graders left back in June 2003.

The true test of the policy will come as these children move through the school system. Proponents say it will help insure that students do not reach high school unable to read well or do math. "If people tell you that social promotion is not an issue in our school system than they just haven't been in our high schools, " Klein said. Thousands and thousands of kids who are basically not reading and not doing elementary math -- that seems to me to be the current crisis in public education."

But many educators argue that retention will not solve that problem. A paper by the Institute for Education and Social Policy at NYU's Steinhardt School of Education and the Center for Schools and Communities reviewed the findings on retention and concluded that students who are left back do not score better on standardized tests later on but instead are more likely to drop out of schools than other students. New York City has adopted such policies in the past only to drop them several years later.

Whatever the educational effects, the mayor seems to have reaped political benefits from the controversy. A poll found that New Yorkers backed the mayor's policy by a two-to-one margin.

BREAKING UP THE HIGH SCHOOLS

While New York boasts some of the nation's top high schools, it also has many high schools where most students fail to meet basic standards for graduation. At Theodore Roosevelt High School in the Bronx, for example, only 15 percent of students passed the required English Regents test.

To address the problem, the Department Education has begun breaking up large struggling high schools into smaller schools. Roosevelt High School is being phased out, to be replaced by four schools. Brooklyn's Erasmus Hall High School, a distinguished school that had fallen on hard times, is now three high schools. Altogether the city opened 42 small high schools last September and expects to open 41 more high schools as well as 15 small combined junior/senior high schools in September.

This is part of a national trend fueled by money from the federal government's Smaller Learning Communities Program and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has given New York $79 million to promote small schools.

But now signs are emerging of a small schools backlash. Critics argue that the schools do not always deliver on their promise. The City Council education committee reported that students in small schools do not perform as well on Regents tests as similar students at regular schools.

As might be expected in New York, school officials must struggle to find places to put the new schools. They often squeeze the new programs into already crowded schools making the congestion worse. Staff and students at the old, big school then complain the new school gets preferential treatment.

HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS

With such great disparities between the ciyt's good high schools and bad ones, the high school application process resembles a winner take all lottery. This year, the Department of Education revamped the procedure, modeling it on the application process for medical residency programs. Students listed up to 12 schools in order of preference and were matched with the school highest on their list that would accept them. But unlike in previous years, students were no longer automatically admitted to their local -- or "zoned -- high school.

At the end of the initial application round, some 14,000 students had not been admitted to any of the schools on their list. The Department of Education provided them with lists of schools that still had openings, many of them new schools or low-performing ones.

Observers chalked the problem up to the general shortage of decent high schools in the city. But in June it was discovered that the new policy had left some seats at top high schools unfilled. This outraged parents whose children narrowly missed acceptance.

Klein insisted the process still represented an improvement over the scramble in previous years, but Miller called for the education department to come up with a new way to match students and schools.

REORGANIZATION

As Bloomberg focused on education, he took aim at a bureaucracy, which, he repeatedly charged, was more interested in protecting its own than educating young people. To shake up that structure, Bloomberg and Klein all but eliminated the 32 community school districts, replacing them with 10 instructional divisions. The city sold the old school headquarters at 110 Livingston Street in downtown Brooklyn and moved a pared down bureaucracy to the Tweed courthouse next door to City Hall.

But the new organization and the turmoil created some problems. Some critics say the department has lost institutional memory and expertise. According to Levy, principals between ages 55 and 60 are leaving in unprecedented numbers. The New York Sun reported that as many as a third of the 113 new local instructional superintendents that Klein hired last year are quitting, frustrated by the demands of the job.

Some operations got lost in the organizational shuffle. The education department eliminated the bureaucracy that reviewed student suspensions, creating a huge backlog in the disciplinary process. This, more than any increase in school crime, gave rise to last winter's school security crisis.

Similar problems plagued special education, which Klein also reorganized. By last winter the New York Times and the public advocate's office reported the system was in disarray, with students languishing in inappropriate settings while awaiting evaluation. Klein has since announced steps to address the problem.

But the confusion went beyond those two programs. Administrators at a leading Manhattan high school told parents last fall that they really did not know who in the Department of Education was responsible for the school.

"With the old Board of Education, people were downright nasty," recalled Brooklyn parent Carmen Colon. "Now they smile and can't help you."

The parent coordinator program was instituted partly to help parents negotiate the bureaucracy, and many consider it a success. "The hiring of parent coordinators has been one of the most positive aspects of the Children First initiative," said Digna Sanchez, president of Learning Leaders, a volunteer program.

But some parents are less impressed. "Parent coordinators are simply middlemen who do nothing but deflect the parents away from the administration," said Colon. "They're a buffer between you and the people who have the answers."

THE TWEED CULTURE

Regardless of what they think about the substance of the reforms, many observers fault the way the changes have been made. The criticism of Klein's management style occurs again and again. "Everybody in the school system except for people at Tweed are frustrated," said Anat Jacobson, spokesperson for Betsy Gotbaum. "Everything has been done behind closed doors and people don't find out about it until something goes wrong."

Because the leaders at Tweed do not consult before instituting new programs, Levy said, "there is little time to clean up these programs prior to rolling them out." The lack of discussion, she said, contributed to the problems with high school admissions and some of the testing programs. Parents too are often ignored and do not have elected board members to turn to for help.

The firing of the dissident members of the Panel for Educational Policy provided ample evidence that this system was one of strong central control. And many New Yorkers, frustrated with the bickering that crippled the schools system for decades, may welcome that. There was, Beam said, "a lot of feeling that something had to give. That's why people are not yelling too loudly."

But some are.

In an op-ed in the New York Times, education expert Diane Ravitch and teachers union president Randi Weingarten wrote, "The school system has been reorganized along the lines of a corporate business model, as though educating children was no different from selling toothpaste. … Not only does the reorganization leave out any role for public involvement, it has also led to serious malfunctioning of school services."

"Everyone complains about the almost pathological secrecy at the Department of Education," wrote Jack Newfield. "This secrecy seems mostly a defense mechanism to conceal amateurish incompetence."

In the interview, Klein denied that top leaders at the Department of Education do not consult with others. But he said, what "is different from the old system, and this I think is good, is that there wasn't a plebiscite on each and every decision. That's the way the board used to work and that was the politics of paralysis."

"The essence of mayoral accountability," the chancellor continued, "is to have the mayor able to implement changes . . . and to be able to hold him accountable for its results."

For Bloomberg, after a year with some setbacks and some successes, that remains both a promise and danger.

Flaws In The High School Admission Process

Roman Kravchenko, an 8th grader in Brooklyn, came to this country two years ago. After one year of English as a Second Language classes at Joseph B. Cavallaro Intermediate School 28, he attained full language proficiency. Now he studies reading and writing alongside American-born students. He got a 94 in English on his last report card and a 95 average overall.

Yet Roman has not been accepted to any of the six public high school programs to which he applied. Now he's one of 14,000 young New Yorkers adrift in an adolescent limbo created by the city's new high school matching system.

Roman came here from Russia to become a boy without a country. As of early June, he and the thousands like him didn't know where they'd be in September. For the first time in New York, they can't even count on attending their neighborhood school.

The latest edition of the "Directory of the New York City Public High Schools" -- the city's instrument for guiding eighth graders and their parents through the high school admissions process -- boasts cartoons, youth-oriented graphics and "fun facts" about famous New York City high school graduates like Lucy Liu and Colin Powell.

But it lacks a comforting sentence that was included in the more humdrum edition of the previous year: "If you received no offers, you will attend the local high school." That is no longer true. Students must list even their local, zoned high school as one of their choices and hope for a match.

Roman wasn't shooting for the moon. His dream is to attend Edward R. Murrow High School, a school popular with Brooklyn's middle class that accepts students of various abilities. He applied to three selective programs there - each counted as one choice - and to another well-regarded school, Madison. He also listed Franklin D. Roosevelt and New Utrecht High Schools. Some might say those last two should have been happy to have him.

Nobody wanted him, perhaps because Roman's high average and swift mastery of English couldn't remedy a fatal flaw: in 7th grade, he'd been placed in English as a Second Language Arts. His official designation as an English Language Learner had barred him from taking the 7th grade state standardized exam in English Language Arts, and high school admissions revolve around 7th grade scores.

Roman had been instructed outright not to apply to high schools with "screened" admissions, which in the arcane parlance of high school admissions, absolutely require the 7th grade English Language Arts test score. But the lack of the score couldn't have helped him with the other schools either.

"When I found out that no school wanted to take me, I thought, what did I do wrong? It's my fault," said Roman.

Such reactions are common in unmatched students. They sound like mugging victims.

Soon, however, Roman found his bearings.. "Even my teachers said, 'It's some kind of mistake. With your average, no school? What nonsense.' That's when I decided to fight back."

He and his mother, Polina, have decided to renew their push for Murrow. Armed with recommendations from Roman's teachers, Polina secured a letter from a Murrow assistant principal agreeing to accept the boy if the Department of Education consents.

In the meantime, Roman was given a list of schools that still have openings and told to rank his choices again for the final round of the admissions process. There were still openings at Madison, and he will soon learn if he was accepted. In late May he didn't feel hopeful: every unmatched kid he knows had ranked Madison first, he said.

He found the other schools on the list unacceptable. "Their graduation rates were less than 50 percent. I was shocked," said the honors student.

If the match system failed Roman because he's a former English Language Learner, it failed another student at his Brooklyn middle school for very different reasons.

Jason Reichman, also an eighth grader at I.S. 281, had considered Murrow, too. But Jason has been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder. His mother, Nancy, said, "When I saw how unstructured and laid-back Murrow is, I said, 'Jason, this is not for you,' and he agreed."

Instead, they looked for a smaller school, where Jason would be sure to get attention. His mother said he does well in all subjects except math, for which he has an individual educational plan.

"He needs a little extra guidance," Jason's mother said. "He's not special ed or a top student. He tends to get lost in the shuffle."

The city has supposedly addressed the needs of students like Jason with the creation of new small high schools set to open in September. In the spirit of we-told-you-so, the city announced that more than 8,000 students who applied to one of the small high schools opening in September were matched to them.

Indeed, Nancy Reichman wanted her son to apply to the new high schools - until she learned that the closest ones were eight or nine miles from her Gravesend home and not on a direct public-transit route. In the end, she found only three schools of acceptable size for Jason to list. Two are highly sought after: Telecommunications and Technology High School and Leon M. Goldstein High School for the Sciences. The third, Brooklyn Studio High School, was a pioneer in mainstreaming special education students into general education classes.

Jason received no offers. "My son felt like a failure," his mother said. "It's a farce. They give them all these choices, and all of a sudden there are no choices."

Like Roman, they were given a list of schools with open seats. Not one met Jason's needs. Because she had to submit something, Nancy wrote the name of New Utrecht High School, affixed the notation "signed under protest," and faxed it to the education department with an appeal.

Jason is feeling better, his mother said, because he knows "I'll continue to fight it even if I have to get a lawyer."

The city's new high school admissions process is said to resemble the match program that admits med school graduates to residencies. But Roman and Jason aren't looking for prestigious places to advance their careers. They're just two kids who want to succeed in city high schools that have failed so many others.

Marcia Biederman writes about city public schools for InsideSchools.org and contributes regularly to The New York Times.

New York Schools: Fifty Years After Brown

|

|

Even parents who can afford private schools send their children to P.S. 6 on Manhattan's Upper East Side. The school offers instruction in political cartooning and foreign language and a joint program with the Museum of Natural History. And all the innovation apparently pays off. More than 92 percent of the students at the school meet the state standards in reading and math for their grade level.

But there is another P.S. 6 in New York City, this one in the East Flatbush section of Brooklyn. Despite a well-regarded principal, only 40 percent of its students meet the state standards in reading and less than a third in math.

The Manhattan P.S. 6 is overwhelmingly white and includes only a smattering of poor students. Its East Flatbush counterpart is more than 92 percent black, with almost 90 percent of its students from families with low enough incomes to qualify the children for a free school lunch.

The differences between these schools reflect the state of education in New York City public schools today, 50 years after the Supreme Court outlawed legally enforced school segregation in the United States. Despite a far greater ethnic diversity, with an increasing number of Asian and Hispanic students, New York City public schools are among the most segregated in the country. But, if integration has not been achieved, few New Yorkers seem to see it anymore as the most important goal in education.

THE BROWN DECISION

On May 17, 1954, when the Supreme Court issued its unanimous ruling in the case of Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, legalized segregation in the country had just started to crumble in the wake of World War II. But separate and decidedly unequal still held sway across much of the country, particularly the South, with black Americans forced to sit in the back of the bus, drink at different fountains, and sit in separate train cars. They were barred from Woolworth lunch counters and could not try on clothes in department stores. Poll taxes, tests with arcane questions and intimidation prevented them from voting.

Linda Brown, a black third grader in Topeka, Kansas, had to attend a school a mile from her home, even though a white elementary school was only seven blocks away. The principal of the white school refused to admit Linda, setting in motion the events that would lead to the historic court ruling.

In defense of its dual school systems, the Topeka school board argued that segregated schools prepared youngsters for the segregated society in which they would live and were not harmful to black youngsters.

After years of argument and deliberation, the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, rejected those claims. In the decision, Warren wrote, "Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn."

Brown and a related ruling "reflected and encouraged developments that would soon spark the burst of humane, bold and heroic action that we now know as the civil rights movement," Eric Foner and Randall Kennedy wrote in a special issue of The Nation magazine commemorating the Brown decision.

Some predicted all schools would be integrated within five years. But change came slowly. In 1955, the Supreme Court ruled that desegregation could proceed "with all deliberate speed," a phrase that many school districts took to mean "as slowly as possible." And so a decade after Brown, less than two percent of black youngsters in the South attended integrated schools.

But the civil rights movement helped change that. And by 1974, 20 years after Brown, almost half of all black children throughout the nation went to white-majority schools. Despite what many call the 'resegregation' of the last few decades, some of that change remains, including in Topeka, the city that gave birth to Brown.

But this is not the story in New York City, where the racial composition of schools today almost resembles those in the South of the 1950s.

Indeed, the city's schools were not much more integrated than Southern schools when the Brown decision was issued -- even though Governor Theodore Roosevelt had directed the New York State Legislature to abolish the last two officially black schools in New York City way back in 1900. But as recounted by Diane Ravitch in her book The Great School Wars, Kenneth Clark, a psychologist whose research bolstered the NAACP arguments in the Brown case, issued another report in 1954 concluding that New York City had a segregated school system and that black children received an inferior education. The head of the New York City Board of Education then, Arthur Levitt, said the segregation had not "been deliberately imposed by legislation" but was nonetheless "not good educational policy."

At the same time, the population of the school system was undergoing a huge change, as many whites left the city for the suburbs, and more and more Hispanics moved to New York. There were many subsequent efforts to address the segregation in the city -- some sincere, some cosmetic, few successful.

NEW YORK'S SEGREGATED SYSTEM

Today, of the approximately 1.1 million students in New York City public schools, about 13 percent are Asian, 15 percent white, 32 percent black and 40 percent Hispanic. Given the makeup of the student body, one reason for segregation of New York City schools, said Pedro Noguera, a professor at New York University's Steinhardt School of Education, is that "there are no kids to integrate with."

But the population of many schools is even more skewed than the student population as a whole. Some 60 percent of all black students in New York State, including those in New York City, attend schools that are at least 90 percent black, according to a recent study by the Civil Rights Project at Harvard University; more Latinos in New York State than in any other state go to schools that are 90 percent or more Latino.

Another study, this one by the Lewis Mumford Center at the State University of New York at Albany, found that Asians and Hispanics are more segregated from whites in New York schools than in any other school system in the country. For black-white segregation, New York ranks third.

The Mumford study also found that, in 2000, the typical black student attended a school where only five percent of the other students were white, a sharp drop from 1970.

This segregation has a different cause than that in the South of the 1950s. In New York, "the segregation in the schools reflects segregation in the housing market," said John Logan, who conducted the Mumford center study. While New Yorkers think of this as a progressive city, it is, Logan said, "one of the most segregated cities in the country in terms of blacks and whites."

But the city has had little success implementing policies that might reduce the effects that housing segregation has on schools.

Particularly at the high school level, the Department of Education established schools with special programs around the city, in an effort to encourage students to leave their neighborhoods. But the effort has not done much to improve integration. Although some of the individual school programs are good, "I don't believe school choice has made New York a less segregated city," said Jill Chaifetz, executive director of Advocates for Children, which works on school issues.

In another attempt to encourage diversity, the city requires that some high schools with special programs admit the same number of students who do poorly on standardized tests as those who score substantially above average. But this gives the lowest scoring students a better chance at admission because far fewer of that group applies. And some parents, many of them white, complain that their children are being unfairly denied a place in these schools.

Partly in response, white parents in several communities have lobbied to bring back the neighborhood high school, at least in their communities. "Despite paying the highest tax rates in New York City, we don't have a school that will prepare our children to go to the superior colleges they are qualified to attend," a proposal by East Side parents said.

The parents won creation of the new Eleanor Roosevelt High School on East 76th Street, but the school admits children from a broad swath of Manhattan, not just the immediate neighborhood, as the parents had wanted. Eleanor Roosevelt, now in its first year of existence, is 10 percent black, 15 percent Hispanic, 35 percent Asian, and 40 percent white.

Parents in the white, affluent Park Slope section of Brooklyn fought to revamp John Jay, a high school attended largely by black and Hispanic students from outside the community. They believed that three new small schools, with grades 6 through 12, would enable more Park Slope kids to attend high school in their neighborhood. They won their fight but may have achieved a Pyrrhic victory. Top students from Park Slope have been slow to embrace the three new schools and at least one is plagued by discipline problems and a poor reputation in the area.

THE EFFECTS OF SEGREGATION

If the schools are still segregated, does segregation still matter? Some would argue that it does.

Claude Steele, a professor at Stanford University, listed some effects segregation has on black students. "They are more likely to go to poorly funded schools in run-down buildings and more likely to be taught by uncertified and poorly trained teachers," he wrote. "They are likely to be counseled with lower expectations. They are more likely to go to schools with few or no Advanced Placement courses, and they are likely to have less access to test-prep courses and related tutorials."

Although there are exceptions, schools in New York City with higher test scores tend to have greater numbers of white and Asian students, while struggling schools are more likely to be composed primarily of black and Hispanic students.

In the 1990s, the community group ACORN charged that many junior high schools in predominantly black and Hispanic areas did not teach students what they needed to know in order to do well on the test for the selective specialized high schools, such as Stuyvesant. In response, rather than improve the program for all youngsters, the city began offering special instruction for selected students. Despite the classes, less than 10 percent of students at Stuyvesant are black or Hispanic.

Black and Hispanic students score significantly lower than whites and Asians on virtually all standardized tests and are less likely to finish high school. About 94 percent of white youngsters in New York State who started high school in 1999 were seniors in June 2003, but only 61 percent of Hispanic children and 65 percent of black students were.

As New York increasingly relies on standardized tests, some critics worry that black and Hispanic students will be most affected. For example, most students at Taft High School and Bushwick High School, both of which are 98 percent black and Hispanic, did not pass even one of the five Regents tests required for graduation. "On the 50th anniversary of Brown, we've come full circle," said Jane Hirschmann of Timeout From Testing. Relying so much on Regents and other tests, she said, "is very unequal and very unfair."

Test proponents argue, however, that the lack of firm standards in education has been discriminatory, awarding black and Hispanic students diplomas but without giving them the skills they need to earn a living or function in society.

Black and Hispanic students also bear the brunt of discipline in the city schools. More than 90 percent of students at Second Opportunity Schools for students serving lengthy suspensions were black or Hispanic, according to Advocates for Children.

Academics, educators and politicians endlessly debate the reasons for these disparities. But one factor could be that, along with the achievement gap, there is a resource gap. Predominantly black and Hispanic New York City spends $10,500 per pupil, about half the $21,000 that the rich -- and largely white -- Long Island suburb of Manhasset spends, Jonathan Kozol has noted. At the same time, many senior teachers avoid poor, minority schools in the city in favor of richer schools.

The gap to some extent reflects the fact that much of the money for schools comes from local tax revenues, and more affluent -- usually white -- communities have more money to spend than the black and Hispanic communities that tend to be less affluent.

But critics charge that New York State does nothing to erase the gap, and some things that make it worse. According to David Jones, president of the Community Service Society, in New York State "school districts with the highest percentage of minority students receive over $2,000 annually less than school districts with the lowest percentage of minority students." He blames the state's method of allocating funds to districts.

THE BENEFITS OF INTEGRATION

The demand for integration is not purely academic. Students who attended the more integrated schools of the 1970s, and those who attend the segregated schools of today, apparently see the value of diversity.

A recent study by Columbia University Teachers College looked at people who had attended school in the peak integration years of the 1970s before courts began rolling back orders requiring busing and other integration measures. While the integration may not have completely reformed society, it did change individual members of the class of 1980.

The study concluded that the integrated schools did more than any other institution, except perhaps the military, to "bring people of different racial/ethnic backgrounds together and foster equal opportunity." And, the people interviewed said they found attending mixed schools "to be one of the most meaningful experiences of their lives, the best -- and sometimes the only -- opportunity to meet and interact regularly with people of different backgrounds."

Today's school children seem to want a similar chance. Advocates for Children conducted an essay contest to mark the Brown anniversary, asking students to write about such topics as whether integration is important.

In the essays, some of which will be on the group's web site later his month, students wrote about the value of diversity, said Deborah Apsel of the group. "There were kids who said we really wish our school had more Caucasian students or kids from outside our neighborhood," she said. "A lot of kids talked about "tolerance" or "about how integration in the classroom builds on the learning and can add a different dimension to discussions."

LESS AGAINST "SEPARATE", MORE FOR "EQUAL"

But experts debate the value of integration.

Derek Bell, a former civil rights lawyer who teaches at NYU law school, said that in some respects Brown was "a disaster." Those who cheered the decision at the time failed to recognize how entrenched segregation and white racism was in America, he said. Rather than trying to do away with separate schools, Bell has argued, the Supreme Court "might have been better off" if it had set out steps, such as monitoring and enforcement, to ensure that black youngsters attended schools truly equal to those for white students.

Others who support integration, such as Gary Orfield, author of the Harvard Civil Rights Project study, question whether meaningful integregation can take place without crossing boundaries between city and suburb. But in 1974 -- 20 years after Brown -- the Supreme Court in Milliken v. Bradley ruled that school integration efforts did not have to cross government boundaries -- in that case between predominantly black Detroit and its white suburbs.

Faced with that and other court decisions that have chipped away at efforts to integrate schools, activists in New York have shifted their efforts to trying to get more funding to improve the schools that black and Hispanic youngsters attend.

In one, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity challenged the formula New York State uses to determine how much money the state gives each local school district. Activists in other states have also argued that poorer school districts need more money to help their students meet new state standards.

In the Campaign for Fiscal Equity case, the state's highest court ruled that Albany's funding formula denied students in New York City and other cities in the state their right to a "sound, basic education," and ordered that the situation be corrected. But the issue remains entangled in politics and disputes about the amount of money required. Neither Governor George Pataki nor the legislature -- nor localities -- have come up with a means to fund the court's mandate. The governor suggested using funds from electronic gambling machines.

Elise Boddie of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund said she hates to choose between fighting for integration and struggling for more money. But she admitted that in light of legal rulings and hostile courts, "Funding equity cases may be our only hope."

That funding, said Pedro Noguera, can lead to better schools and maybe even more integrated ones: "If you can get really outstanding teachers into high-need areas and really outstanding programs . . . then you're going to attract middle-class kids of all races," he said. "Quality is what is ultimately going to bring people in, -- whites and Asians as well as middle-class blacks and Hispanics."

But it will be a long hard road. And many experts, while recognizing the promise of Brown, see few reasons for optimism on its much-observed anniversary.

Teaching Certificates Are Tougher To Get

On a recent Saturday, a young woman passed out free red pencils in front of Bishop Kearney High School to adults filing into the building to take state-required teacher certification exams. The pencils were a gift of New York Urban Teachers, one of several expensive Department of Education projects aimed at streamlining the Byzantine certification process.

But inside the building, the pencils generated confusion and a warning.

"Do not use them," an exam administrator advised test-takers preparing to fill in dozens of bubbles on question sheets. "We have no way of knowing if they are No. 2."

Indeed, the pencils bore a catchy slogan - "Bringing outstanding certified teachers to NYC public schools," but no indication of lead hardness. The most vital information just wasn't there.

The pencils were emblems of the failures of the city's much vaunted teacher recruitment efforts. Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg announced the latest of these last month, a glitzy campaign sponsored by the Ad Council said to be the most ambitious in the city's history. The mayor promised TV commercials and billboards that would help attract the city's "largest pool of teaching candidates."

Like the useless free pencils, glitzy ads cannot help the majority of people who already want to be city teachers, but who now face

• heightened certification requirements,

• long delays in application processing,

• and a hiring culture that favors the well connected over the merely qualified.

HEIGHTENED REQUIREMENTS

On Feb. 1, requirements for a teaching certificate jumped significantly, even as the starting salary for most city teachers remained a modest $39,000. On that date New York State changed the requirements for entry-level teachers. First-time teachers sending paperwork after the deadline could no longer get a provisional certificate, which had allowed them to postpone one of three standardized exams until after they started work and demanded slightly less - or, in some cases, just different - coursework.

Tom Dunn, a spokesman for the state Department of Education, said the state toughened the requirements to comply with a portion of the federal No Child Left Behind act (PDF Format) mandating measurable state efforts to improve teacher quality by 2006.

"It's a national trend," Dunn said, adding, "We have no interest in certifying unqualified people as teachers."

But will the new regulations really produce better teachers? Depending on the certificate sought, applicants might need no more than two or three extra courses than they would have in January. Still, that could be a major deterrent for people who lack three credits of "information retrieval" - that is, a computer course -- now required for most teaching certificates.

Even before February, certificates required passing grades on two standardized exams - one in liberal arts and sciences, the other in teaching skills - each costing $70 for registration. With the addition of the third exam, the so-called "content-based test" on the subject to be taught -applying for a certificate costs an average of $500; added to the exam costs are fees for fingerprinting, application processing and required workshops, most of which have risen recently.

There is, of course, no guarantee that the applicant will be awarded a certificate, and then a job, after these expenses.

A LONG WAIT