After-School Programs Lose Funds

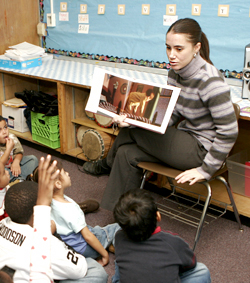

Every afternoon during the school year, tens of thousands of New York City children stay after school, and many of them like it. While they enjoy activities, such as arts and crafts, games and homework help, their parents welcome the sense of security from knowing their children are safe, occupied and well taken care of.

But for 20,000 city students that could change this year. In New York City, 118 after-school programs will face major budget cutbacks, and some will have to shut down entirely. The federal government’s 21st Century Community Learning Centers program has declined to offer the programs another year of funding. Although the programs also receive support from New York City and New York State, Washington was the main source of funding. The learning centers’ funds were distributed through the state education department.

The endangered programs, which have been receiving funds since 2003, have been barred by the federal government from applying for a new round of money.

THREATENED PROGRAMS

Good Shepherd Services funds two after-school programs in the Bronx, one at MS 206, the Ann Mersereau School, and the other at M.S. 118, the William Niles School. The programs offer arts, science, homework help, student government, peer leadership and community service. But the center has already informed parents that the programs might close down and has warned staff about lay-offs. Each of the programs has one full-time employee and 20 part-time workers

|

Conflicts and Resolutions Police in the Schools: Hanging Out and Hurting Business: Breaking the Cycle of Violence: Taking A.C.T.I.O.N. at The Point: Cutbacks After School: |

“Unless we raise funds we can’t support the programs. We need $185,000,” said Jim Marley, director of Bronx Network for Good Shepherd Services. “It’s terrible and unfair. Children do great in these programs. It’s a proactive and positive approach, and they don’t get into trouble.”

In Bay Ridge Brooklyn, a non profit organization, offers an after-school program at PS 170, the Lexington School. This program serves 220 students and has a waiting list of 60.

Christie Hodgkins, director of after-school services at CAMBA, said that the program will remain open but will have to scale back. ““We know we are going to have to cut 60 to 80 slots and that is significant because there is already a need greater than what we are providing,” she said.

Even programs that will not feel the effects of the cuts immediately fear for their futures. Global Kids, a nonprofit organization that focuses mainly on after-school programs for high school kids, has sufficient funding for at least two years. But the organization’s director for after-school programs, Evie Hantzopoulos said, “We don’t know what’s going to happen two years from now. Every year this is the challenge of doing youth development and nonprofit work: anything can happen from year to year because there isn’t enough of a commitment I think from our government.”

A coalition of schools, community and youth leaders secured $7.5 million from the state for the threatened programs. But this number falls $23 million short of the amount needed to fully fund all endangered programs for another year. Lucy Friedman, president of the After-School Corporation, which supports programs in 322 New York City schools, said foundations could make up some of the shortfall. Advocates also hope the state will come through with additional funding.

FILLING A NEED

Proponents of after-school programs say they offer an array of benefits. Friedman said that, besides providing a safe place for students to be after school, they also help students academically.

“They help because [the students] are engaged in activities -- whether it is karate or dance or photography. They are engaged in activities that help them advance, but also keep them off the streets or being home alone,” she said. “Those are hours that are most dangerous for kids both in terms of getting involved with drugs, getting pregnant, a time when they find trouble and trouble finds them.”

According to a report by Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, a national anti-crime organization, juvenile crime is more frequent between 3 to 6 p.m. As a result, after-school programs help decrease crime rates.

The Afterschool Alliance, another national nonprofit, conducted a formal evaluation of after-school programs and how they affect kids’ behavior, safety and family life. The group’s report concluded, “After-school programs help keep children safe, have a positive impact on behavior and discipline, and help relieve parents’ worries about their children’s safety.’’

And the need for such programs, supporters say, does not stop when children become teenagers. Hantzopoulos said high school students in particular require dynamic and meaningful after-school programs because they are going though a transitional stage.

“They need these opportunities because they want to do positive things, and we have a responsibility to provide them with programs that will help them develop, succeed, make a change and feel good about themselves,” she said. “Sometimes we are too quick to penalize them, put them in jail.” Arguing that it is “in our best interest to provide more tax dollars for after school programs,” Hantzopoulos said, “Maybe if we had more resources we wouldn’t have some of the situations we have right now.”

Â

Poor Grades for a School 'Contract'

As the fight to get more state money for New York City public schools wended its way through the courts for more than a decade, educators, parents, politicians and others occasionally stopped to fantasize: What would we do with all that money?

Now, with the 14-year-suit having reached a somewhat anticlimactic conclusion and the city set to receive an additional $3.2 billion from the state over the next four years, New Yorkers are learning the answer to that question, and some education activists do not like it. Complaining that they have been shut out of the process, many want the city to spend more to reduce class size and improve middle schools -- and less on testing and charter schools. The dispute, aired at hearings throughout the city in early July, is about money to be sure, but it also concerns setting priorities for the nation’s largest school system and how success -- or failure -- should be measured.

THE MONEY

The additional funds signal the end of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit brought in the 1990s. Under the state system of funding education, it charged, New York City schools did not have enough resources to provide public school students with the “sound, basic education” they are guaranteed under New York’s constitution. With the state’s highest court issuing its final ruling in the case late last year and a new governor in Albany, the state earlier this year agreed to give the city’s Department of Education an additional $700 million in state education funds for fiscal year 2008. This represents New York City’s share of the almost $1.8 billion hike in state education aid proposed by Governor Eliot Spitzer and approved by the legislature.

SPENDING IT

The largest chunk of the new state funds for New York City -- $334 million -- will go toward raises and fringe benefits approved in recent contracts with teachers and other school employees. The Department of Education will spend a bit more than $100 million on special education, another $213 million on pre-kindergarten programs and charter schools, and almost $150 million to help defray increased operating costs, particularly rising energy expenses.

But the bulk of the controversy surrounds the remaining $228 million. The state legislation dictates that districts use some of the new funding to finance improvements thought to boost student achievement: smaller class sizes, more learning time for students, full-day pre-kindergarten programs, efforts to improve teacher quality and restructuring of middle schools and high schools.

To receive this money -- $228 million in the city’s case -- the Department of Education has had to prepare so-called Contracts for Excellence describing how they would spend it. According to those contracts, the city will use about half the money to cut class size, with the remaining funds divided among the other four areas.

Schools Chancellor Joel Klein announced this plan on July 5 -- about a week after school had closed for the summer and in the middle of a lazy week interrupted by the Fourth of July holiday. The department scheduled hearings in each of the five boroughs for the following week. By July 15, a revised plan would be sent to the state Board of Regents for approval.

The summer doldrums did not prevent a quick -- and generally critical reaction -- to the city’s plan. In a statement, Geri Palast, executive director of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity charged that the city’s contract “raises more questions than it answers” and “lacks the necessary specificity and transparency to understand where and how the money will be spent.”

DEBATING THE PLAN

The controversy over the contracts echoes many other disputes that have surrounded public education in New York City since Mayor Michael Bloomberg took over the school system in 2002 and installed the Department of Education in the Tweed Courthouse.

Parental Involvement

The state legislature did not pass the law setting up the system and authorizing the funds until April, Excellence Inside Schools has reported. This gave the so-called “educrats” with offices in the Tweed Courthouse little time to devise a plan and put it out for public scrutiny and comment.

But that did not stop many critics from assailing the midsummer hearings. “The fact that these hearings are being held with no outreach to parents and community members, in the dead of summer, is indicative of tepid commitment of our Department of Education to the spirit of CFE,” City Councilmember Robert Jackson, the original plaintiff in the suit, said in testimony. While the hearings “technically comply” with state requirements, “they are implemented in such a way as to actively discourage widespread parental and community input,” he said.

At the Brooklyn hearing, held in a hot auditorium with a faulty sound system often overpowered by crying youngsters in the back (the Spanish translator was particularly difficult to hear), several speakers accused the department of simply going through the motions. “The only reason you’re having this hearing is it’s a required part of the Department of Education receiving the money,” the mother of a fifth grader complained.

The Department of Education representatives, some more attentive than others, did not respond to comments from the audience.

In the Bronx hearing, held on a sweltering Monday night, Ronn Jordan turned to sarcasm. “Good job on having this hearing without giving parents any notice,” he told the education department officials. “Maybe next month you could have it in the middle of the night at an undisclosed location because I think you got too many parents here.

To some parents and teachers, the hearings were another indication of what many see as the Department of Education’s high-handed ways. While the administration has installed parent coordinators in every school and set up a variety of advisory panels, critics say that the panels tends to be toothless, and Tweed prefers to get reactions after it has made a decision -- rather than taking the opinions of parents, students and teachers into account when formulating policy. The issue erupted earlier this year when the department, without consulting parents, altered city school bus routes, leaving many students with long waits or no transportation at all on some of the coldest mornings of the year. In the uproar that followed, the administration created the job of chief family engagement officer, and appointed Brooklyn parent and education activist Martine Guerrier to the post.

But many remain suspicions. Surveying the education officials, who he described as “Ivy League thoroughbreds with business and management degrees,” teacher Jeff Sorkin told the Brooklyn hearing the “plan is one again dictated by us by the Department of Education.”

Class Size

The city proposes adding 1,300 teachers and 400 new classes at a cost of $106 million next year. While that sounds like a lot of teachers, critics calculated it would cut class size by just a third of a student per room in the lowest grades.

At the July hearings, teachers describe how hard it is to deal with dozens of students at a time. Julie Woodward, a high school music teacher in the Bronx, cited classes with 50 teenagers, according to a transcript of the proceedings. “The chancellor shows no concern for the differences that you have to account for as a teacher. We’re talking 9th grade through 12th grade, special ed, regular ed, hearing impaired, all in the same class,” she said, adding that Klein “continues to direct us to teach everybody equally and demands that we justify personal attention to every kids’ needs. This is outrageous and it’s impossible.” A Brooklyn middle-school Spanish teacher described the challenges of helping a class of 39 students “try to grasp an unfamiliar language….It is not fair to them.”

“I don’t understand why Tweed cannot listen to teachers,” Dianne Stillman, an English teacher from John F. Kennedy High School in the Bronx, said. “What is so difficult? Teachers have been telling you in high schools, give me 20 students in a class and I can reach the stars. What is so difficult about that?”

Bloomberg and his chancellor have repeatedly downplayed the role that smaller classes play in improving student performance. The administration successfully blocked a question on reducing class size from getting on the ballot, and in a proposal to improve education submitted to the courts in 2005, did not mention reducing class size. Klein has said repeatedly that students are better off in a large class with a good teacher than in a small class with a mediocre one. Class size only emerged in the Contract for Excellence because many principals pushed for it, according to the New York Sun.

Middle Schools

With grades six through eight generally considered the weakest link in the education system, many advocates urged that more money be focused in middle schools. Although the new budgeting system for city schools, called Fair Student Funding, is supposed to provide extra money to needy students and schools, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity and the New York City Coalition for Educational Justice say that many of the city’s worst performing middle schools will not see any additional funds. In these schools, a third or less of students meet the state standard for reading.

The advocates would like the Contracts for Excellence to redress this, putting more money into failing middle schools.

The fight over aid to middle schools is likely to receive increased attention later this year when a task force, appointed by the City Council and headed by New York University educator Pedro Noguera releases its recommendation on improving education for the city’s adolescents.

Setting Priorities

Speakers at the hearings also faulted the contracts for not spending more money on the city’s poorest and worst performing schools, on pre-kindergarten programs and on English language learners. And along with criticizing the plan for not spending in certain areas, some critics assailed it for what it does spend. In her testimony at the Bronx hearing, Randi Weingarten, president of the city’s United Federation of Teachers, called the proposal “a plan to fund the city’s own agenda.” For example, she noted, it sets aside $42 million for new testing.

The contracts also include money for publicly funded but privately run charter schools -- schools touted by Bloomberg and Klein as a means to offer parents and students more choice. But Michael Rebell, a lead lawyer for the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, questioned the way these schools were treated. “Why should money going to charter schools be less accountable than money going to public schools,” he asked the Sun.

THE ACCOUNTABILITY QUESTION

Numerous critics charged the outline for spending was vague, making it difficult to hold the educators responsible for it. “The proposal presented fails to provide any particulars regarding when or where new class space and new teachers will be added. There are no construction plans, timetables, or identification of which schools will receive more classrooms and teachers,” Assemblywoman Catherine Nolan of Queen, chair of the Assembly Education committee has said.

Paul Egan, District 11 representative for the UFT, found the vagueness of the proposal ironic for a system “that’s asking for accountability from teachers, for a system that’s asking for accountability from specific data.” On class size for example, the plan calls for additional classrooms and teachers and sets out some general parameters but does not detail where the additional teachers will go. It does not detail how the city will assess whether the program has been successfully implemented and what plan, if any, Tweed has to further reduce class size in the years ahead.

Under the state law, the city is supposed to submit a five-year plan to reduce the number of students in each city classroom, according to Leonie Haimson of Class Size Matters. But, she said, the contracts fail to do that and offer “no real benchmarks, no goals, no timetables, not enough resources to the schools that need them most, and not enough space.”

And so some speakers urged the state to do for the Department of Education what the department proposes to do for principals, teachers and students: hold it accountable.

“No one wants the mayor and chancellor to fail in their efforts to improve our schools,” Patrick Sullivan, who was representing Borough President Scott Stringer, told the Manhattan hearing. “However, if they continue their refusal to plan for and spend new state funding as intended, the state must hold them accountable.”

Assemblymember Jim Brennan, who told the panel in Brooklyn he helped write the law creating the Contracts for Excellence, called on the department officials to heed the comments aired throughout the evening. And, he said, he would urge the state education department to make sure they do just that.

Education's Difficult Stage

Photo: Ruby Washington/The New York Times

On most mornings about 1,000 students show up at I.S 287, the Christa McAuliffe School in Bensonhurst Brooklyn. Whatever gripes they have about having to go to school and whatever adolescent angst preoccupies them at the moment, they are by most accounts lucky to be there. "The teachers are great, and even though there is overcrowding in such a small school, … you still get individual attention," one student told Inside Schools. “Not only have I learned so much, but I made great friends at Christa McAuliffe," another wrote.

McAuliffe is one of New York City’s approximately 600 middle school programs, and by many measures, it ranks near the top. To get in students must score well on standardized fourth grade tests, with priority given to those who live in the area.

But Christa McAuliffe and other highly regarded public middle schools in the city are seen as the exception rather than the rule. Thousands of the city’s approximately 200,000 sixth, seventh and eighth graders attend school that the state department of education cites as failing. Many feel unsafe in their classrooms and hallways. And more than half spend their days in schools where most of their fellow students cannot read or do math at their grade level.

Some hailed test scores released last month as an indication that New York has begun to solve its middle school problem. Almost 49 percent of city eight graders met state standards on the reading test, up from 36.6 percent last year. But the middle school scores still represent a dramatic falloff from elementary school: 56 percent of fifth graders met the standards.

The years between elementary school and the start of high school are generally viewed as education’s problem stage. While education from pre-K to post graduate poses challenges, the age of the students, the structure of the system and the training for teachers make the middle school level particularly daunting. Why is middle school education such a quandary? And what can New York City do about it?

MIDDLE YEAR SLUMP

After years of neglect, middle schools have begun to attract increased attention from educators, politicians and journalists. Throughout the country, "this is a time of middle school experimentation," education reporter Jay Matthews wrote in the Washington Post.

In New York City, the new school budgets released in May increased funding for middle schools. The Department of Education has enlisted the Academy for Educational Development, an independent nonprofit to help failing middle schools in the city and is looking for other ways to improve education at this level. Citing poor test results, the City Council has created a task force on middle school reform chaired by New York University education professor Pedro Noguera.

Why are policy makers turning their attention to middle schools?

It is partly a result of No Child Left Behind. Under that federal law, middle school students must take standardized tests and meet state proficiency standards. The tests bolstered what many educators suspected all along -- that middle schools tend to be the weak link in U.S. education.

Last year’s poor test results for New York State eighth graders spurred schools to act, according to state education commissioner Richard Mills. “Last year was a dramatic moment,'' Mills told the Times recently. ''I think that was a very sobering picture for people.”

Then too, the middle school problem may have become too big to ignore. Many educators believe the ills facing urban high schools, particularly high truancy and dropout rates, have their roots in middle school.

The middle school years “are marked by a precipitous decline in test scores … which directly affects high school acceptance and drop out rates,” wrote Evelyn Castro, associate dean of the School of Education at Long Island University’s Brooklyn campus.

The city’s middle schools are “failing our children dramatically,” Carol Boyd of the Coalition for Educational Justice told a reporter earlier this year. “By the time they reach high school, they are so far behind that they’re so frustrated, they have no alternative but to drop out.”

Of the nine schools added in January to the state's list of badly failing schools, eight were middle schools.

Even with the jump in test scores, most eighth graders do not meet state standards for reading. And the problem is worse at schools with large number of black and Latino students. An analysis of the 2006 test scores, done by the Annenberg Institute for School Reform for the Coalition for Educational Justice, found high performing school were less than half black and Latino, while low performing schools had student bodies that were virtually 100 percent black and Latino.

Various experts question the validity of the tests. Jill Herman, a former middle school principal now with the Urban Academy, a private group that creates public schools in New York, questions whether in some years the eighth grade test has been too difficult, creating low scores that have fueled “alarmist” talk about middle schools. Others wonder whether the 2006 test was easier than previous exams, accounting for the rise in score.

But numbers aside, most experts concur that middle schools have a long way to go, as Schools Chancellor Joel Klein has acknowledged. Discussing overall test results for the city, he said, "It's a question of whether the glass is half empty or half full." In his opinion, "it's clearly half full.” But Klein does not seem to have a sweeping vision for middle schools. In an interview with Gabe Pressman on WNBC earlier this year, Klein said, “The big crisis in middle school is we’ve got to get more high quality teachers.” He offered few specifics about how he hoped to accomplish that.

HISTORY LESSON

Klein is hardly the first educator to face the middle school conundrum. Students used to stay in one school from first through eighth grade, when many ended their formal educations. But that began to change early in the 20th century, as the first junior high schools in the country opened in 1909. By the 1930s, New York City saw a sharp increase in the number of these schools “in part to relieve high school congestion but also to provide a place for vast numbers of overage elementary school children,” Diane Ravitch writes in The Great School Wars.

In the 1950s, so-called middle schools began replacing junior high schools. The distinction remains obscure to many parents and teachers, but according to Ron Banks of the Clearinghouse on Early Education and Parenting, “The middle school movement builds on the junior high school core curriculum,” but also sought to address the adolescents’ emotional needs.

New York City’s middle school program includes schools dubbed I.S. (intermediate school), M.S. (middle school) or J.H.S (junior high school). Such designations seem more a matter of tradition and convenience than anything else.

Whatever it called the schools involved, New York City has tackled middle school reform before. In the 1970s and 1980s, District 4 in East Harlem, in an effort to fight poor academic performance, eliminated neighborhood middle schools and started a number of alternative schools to which students had to apply. Other districts, notably District 2 in Manhattan, copied that approach. The schools there remain among the most sought after in New York. But specialized schools, although copied by other districts, provide no guarantee of success.

While Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Klein have made major changes to the school system, at least until recently, they did not focus much on middle schools. The report on city middle schools by the Coalition for Educational Justice charged that the administration has continued “the pattern of neglect,” saying, “The administration has directed far more energy, resources and organization change efforts toward elementary and high school transformation than to middle-grade reform.”

THE MIDDLE SCHOOL CHALLENGE

Middle school reform, Hayes Mizell, author of a book on the subject, is “the most difficult and important work imaginable.” What makes it so hard -- and what is New York trying to do about it?

Adolescent Angst

No one doubts that middle school students present a particular challenge. “It’s the age -- all those raging hormones,” sigh parents and teachers.

Unlike the old junior highs, which focused largely on academic and vocational classes, middle schools were intended to help ease the passage from child to teen. Teams of teachers would work with the same group of students throughout the day and students would regularly attend advisory sessions consisting of no more than 20 kids and an adult.

But some critics say most schools never implemented such programs. “Communities reorganized their former junior highs as middle schools; in reality, the new middle schools don't operate much differently than the old junior highs did,” one middle school teacher has written. This is certainly the case in many New York City middle schools.

But other experts say middle schools focus too much on the emotional life of their adolescent students. Chester Finn, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, has disputed the notion that middle schools “should be devoted to social adjustment, coping with hormonal throbs and looking out for the needs of the whole child.” Instead, he wrote, “There’s nothing about kids this age that undermines their capacity to learn.”

Patrick Montesano of the Academy for Educational Development rejects the idea that school must choose between addressing academic and emotional needs. “It’s not either or at all,” he said. “You’re attending to academic rigor partly by understanding what their emotional needs are.”

School Structure

School Structure

Faced with the failure of so many middle schools, some educators have decided the best solution is to simply get rid of the whole idea, folding the middle grades into elementary schools and creating a throwback to the old kindergarten through eight schools or combining the grades with high school in a six-to-twelve secondary school. New York City is trying both approaches, though most kids still go to separate middle schools serving grades six through eight.

Jill Herman said that there is no one model for middle school structure. In general, though, she thinks it makes sense to combine the adolescents with older or younger students. “The notion for me is that to isolate that age group does not serve them well,” she said, “because they’re not grounded in anything other than their own behavior.”

New York has extended 42 elementary schools to last until grade 8, following Philadelphia’s lead in creating K through 8 schools. "The fifth to sixth grade transition is just too traumatic. At a time when children are undergoing emotional, physical, social changes, and when they need stability and consistency, suddenly they're thrust in this alien environment," Philadelphia school superintendent, Paul Vallas, has said.

Others say that putting middle school kids in with high school students offers them a more serious academic environment. A number of New York City’s new smaller schools, along with some charter schools, include youngsters from 11 to 18 years old. The principal of one such school, the Frederick Douglass Academy, says the extra time is key to getting students ready for college. "I can absolutely get all these kids to college if I have them for seven years," the principal, Gregory Hodge, told the Times.

But many express skepticism. A John Hopkins University study found the K through 8 schools did not improve achievement. “District after district is getting misled by thinking our K-8 schools are doing better than our middle schools,” Douglas Mac Iver, one of the study’s authors, told reporters. “The grade span itself is not some magic bullet.”

Deborah Kasak of the National Forum to Accelerate Middle-Grades Reform agrees. “The middle grades are not about what grade levels occupy a building but what happens in any building to meet the learning needs of children ages 10 to 15,” she wrote.

Failing Schools

With so many middle schools on the state’s list of badly performing schools, the city has shut a number of them. But many then reopen in new guises. For example, the Department of Education closed the South Bronx’s I.S. 183 in 2003. Now the same building houses four new schools -- two of them small middle schools.

Unfortunately, a number of the reconfigured schools continue to fail Of the eight middle schools placed on the state list of failing schools in January five reportedly had been closed previously and reopened under new names. Of the two regular middle schools in the former 183, one -- 203 was on the state list. A reporter from Inside School found, “MS 203 has a long way to go before children are up to par academically.”

A Smorgasbord of School

In much of the city, students apply to middle school rather than simply attending a neighborhood school. In theory, this allows a child to attend the school that best suits his or her needs. And the competition among schools is intended to spur all of them to improve.

Parents in Manhattan’s District 2 express some satisfaction with the system. In other parts of the city, parents complain that the application system is cumbersome and time consuming as students try to determine not only which school they like best but also which one might admit them. To make matters worse, middle schools in New York have been the purview of community school districts, each with its own method of selecting students. Some districts accept students from outside their districts, others do not.

And not getting into the “right” middle school can have a huge impact on a kid. The Coalition for Educational Justice found that most higher achieving schools select prospective students on the basis of test score, grades or other criteria. And so, its report stated, “An average sixth grader who is not accepted into one of these selective middle-grade schools is almost guaranteed to end up at a school where the majority of students will graduate unprepared for high school.”

Klein has promised improvements in the application process, perhaps in time for next year’s fifth graders. One goal, he said, would be making the system fairer, awarding spots “based on performance, not on who you know."

But for now, the Department of Education does not provide much help. Its web page on applying to middle school is blank.

Council Speaker Christine Quinn also views the application system as a problem. In her 2007 State of the City speech she said, "Applying to middle school makes solving the DaVinci Code look simple" and urged the education department to create "school navigators" who would " specialize in explaining the transition process for elementary, middle or high school." So far this has not been implemented.

Getting the Right Curriculum

In their call for a Marshall plan for city middle schools, the Coalition for Education Justice said all middle school students in the city should have “access to a rigorous and varied curriculum” that includes high school-level math and science courses. Not having access to such courses in middle school, the report says, virtually precludes students from taking Advanced Placement courses in high school. But, according to the coalition, none of the low performing school it studied offered one particularly important course -- accelerated math A.

Students with Varied Skills

Student achievement in all but the city’s most selective junior high schools runs a huge gamut. This gap in individual classrooms tends to narrow in high school, as students are divided between honors and regular classes and select schools and courses that reflect their interests and skills. But most junior high school students are lumped together, leaving the teacher to meet the needs of students who can barely read while challenging those who easily handle material intended for adults.

To address that, says Patrick Montesano said, “faculty and students have to roll up their sleeves and dig into the data” to figure out how to best serve different groups of students. Beyond that, he says, schools must carve out room in the schedule to offer extra help -- tutoring, mentoring and after-school and Saturday programs -- for those who need it.

To address that, says Patrick Montesano said, “faculty and students have to roll up their sleeves and dig into the data” to figure out how to best serve different groups of students. Beyond that, he says, schools must carve out room in the schedule to offer extra help -- tutoring, mentoring and after-school and Saturday programs -- for those who need it.

A Shortage of Teachers

While adolescents are in many ways the most challenging students to teach, by some measures, middle schools get the least qualified teachers. More than half the elementary and high school teachers in the city have taught for five years or more, but less than half of middle school teachers have. They are also less likely to have proper licenses and certification.

New York offers a special certificate for teaching middle school, but it is not required. And, according to the Times, of the city’s more than 13,000 middle school teachers, only 82 were “middle school generalists.”

Some teachers end up in middle school because it is easy to get a job in one. ”Many people don’t want to be with that age group,” said Jill Herman. “Unfortunately most people don’t experience the joy of middle school kids.”

Even those who are prepared to appreciate this age group may need guidance on working with them, said Montesano. “A seventh grader is not like a fourth graders and not like an eleventh grader,” he said. “Teachers and administrators have to become experts at understanding adolescent behavior.”

Class Size, School Size

Although most of the discussion about class size has focused on the younger grades, some experts believe smaller classes can benefit older kids as well. The Coalition for Educational Justice recommends no more than 20 students in a class. According to the Independent Budget Office , the average city middle school class during the 2004-2005 academic year had 27.4 students.

In general, the Bloomberg administration has minimized the importance of reducing class size in boosting student achievement. By creating a need for more teachers, Klein has said, smaller class sizes could actually lower the quality of teaching in the city. But now that principal have more autonomy, the Department of Education has said school administrators will be able to reduce class size in their buildings -- if they think that that is the best use of resources.

And Herman thinks many of the city’s middle schools, which can have 1,800 students or more, are simply too big. “Given all the issues kids and families face, its better to have an environment where they’re know well,” she said. The Department of Education has enthusiastically promoted small schools at the high school level but has not devoted much attention to it for middle school students.

THE GOOD MIDDLE SCHOOLS

Earlier this year, the Washington Post's Jay Mathews asked readers to submit their nominations for the best middle schools -- public and private, urban and suburban -- in the Washington, D.C. area. Despite all the complaints about middle schools, dozens of schools were nominated.

After reviewing the suggestions, Mathews concluded, that a good middle schools should have "a principal liked and respected by parents, teachers who are imaginative and willing to give more time to students who need it, extra activities and traditions that intrigue this age group, and high standards for all children."

Most New York City teachers, parents and students would probably agree. But unlike instituting another test or moving sixth graders into a different building, it is not easy to accomplish.

Reorganizing the Schools (Again)

The adjustments to the city’s school system announced by Mayor Michael Bloomberg in his State of the CityÂ

Military Recruiters In High Schools

Andrew Morgan was happy that the military had a presence in his high school.

Morgan attended Thomas Jefferson High School in Brooklyn, which was named one of the lowest-performing schools in New York City. But Morgan was the “commanding officer” of the Marine Reserves Officers Training Corps (ROTC) program in the school, and, as he wrote to InsideSchools.com, “it gave me the motivation to excel in school and to work hard at everything I do.”

There are at least 60 such programs in high schools throughout New York City. In some ways, these ROTC programs are the least controversial of the efforts by the military to recruit high school students in New York.

But critics have been complaining loudly about the direct presence of military recruiters in city high schools especially in poor neighborhoods.

“Recruiters are taking advantage of these students and making a lot of claims about the military that do not hold true,” charges Ari Rosmarin, coordinator of The New York Civil Liberties Project On Military Recruitment and Students’ Rights. Its Web site says that parents, students and educators have been complaining that “recruiters are using heavy-handed tactics to harass students, violate students’ privacy rights, and target poor students and students of color.”

The federal education law No Child Left Behind requires that military recruiters be able to enter schools, participate in recruiting fairs and in general have the same access to students that college and trade school representatives do. Further, schools are required to provide the military and colleges with students’ names, addresses, and telephone listings -- unless the students’ parents request that this information be made unavailable.

If parents do not want their child’s name given to the military they must complete an opt-out form.

What the critics charge is that the military recruiters are being given more access than other recruiters, and that few parents even know about the opt-out forms.

In response to such concerns, Schools Chancellor Joel Klein has agreed to review military recruiters’ access to high school students.

Military Recruiters’ Access to Students and Information

The military gets, keeps and distributes information on students through the Joint Advertising Market Research & Studies. Run by the Department of Defense, this database is used to distribute information about military services to large audiences and helps collect data for recruiting and retention efforts.

The New York Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit against the Department of Defense in 2005 charging that the program collects private student data such as social security numbers, grade point averages and even student interests for the purposes of recruitment

On January 9 the Department of Defense agreed to settle the lawsuit and announced it will make major changes to the information program. They will no longer collect social security numbers and will stop disseminating student information to law enforcement, intelligence and other agencies not related with military recruitment. The Department of Defense has also agreed to establish and clarify procedures by which students can block the military from entering information about them in the database

Leslie Kielson, of United for Peace and Justice, said she would like the Department of Education to ensure that military recruiters are not granted more favorable treatment than other recruiters. The group wants the schools to make more efforts to ensure that parents know they do not have to make their child’s information available and would like a log to be kept to record the number of visits recruiters make to individual schools.

“All of these things are within the power of the city to adapt,” Kielson said. “The No Child Left Behind act says recruiters deserve equal access but they are really getting unlimited access, which means many schools are not following the laws.”

Large cities like Los Angeles, Austin and Seattle have already adopted policies concerning military recruiters’ rights and limitations, Rosmarin said, but New York City has not created any guidelines.

“Schools are not supposed to be a feeder system for the military. Schools should be able to protect their students from being taken advantage of,” he said.

Student Information: Opt-Out or Opt-In?

In November, anti-war groups rallied at the New York Department of Education headquarters to press the school system to do more to let parents know about their opt-out option.

“We’ve heard over and over from the parents we have talked to at parent-teacher conferences that they didn’t know about the opt-out forms,” Kielson said. “It should be the school’s responsibility to inform parents about these options.”

In 2002, 18 percent of New York City’s 300,000 high school students opted out according to a report by the Policy Research Institute for the Region at Princeton University.

Kielson said she will push for an opt-in option when No Child Left Behind comes up for reauthorization later in the year. This would keep student information private unless the parents authorize its release to the military. She hopes the new Democratic majority in the House of Representatives will support such a measure.

“We will be reminding public officials that this election was a clear message for peace,” Kielson said. “There is support for us.”

Recruiters and the No Child Left Behind Act

Rosmarin said there is an overwhelming military recruiter presence in schools like Christopher Columbus, Harry Truman, Abraham Lincoln, George Washington and Martin Luther King, which mostly serve poor, lower-income students. Recruiters are on these campuses at least every other day and become a constant presence in the students’ lives, he said.

“In the recruiters’ manual there is a lot about school ownership,” Rosmarin said. “They are encouraged to befriend the administration, become coaches for sport teams and organize after-school activities. We hear a lot of instances where recruiters will go as far as taking a student out and buying them lunch. We just want to ensure students are given the right to pursue an education without being harassed and hassled everyday.”

Marge Feinberg, a spokesperson for the Department of Education, said college recruiters and military recruiters have the same access to public schools, and neither is given special accommodations.

Emily Gockley, chief of public affairs for the New York City Recruiting Battalion, said it is only fair to allow the military equal access to students.

“Every school decides differently on how they deal with recruiters,” Gockley said. “But if they invite college recruiters they must also invite military recruiters. We are also entitled to get the same information they give out to colleges.”

Neither the school system nor the military could provide statistics on how many recent high school graduates in New York City join the military every year.

All-Volunteer Army: Added Perks, More Recruiting

Even if such programs were restricted, recruiters would still contact students, says Tod Ensign, director of Citizen-Soldier and author of “America’s Military Today: The Challenge of Militarism.”

“It’s a good cause, but the military recruiting techniques are far more sophisticated today,” Ensign said. “I mean, they’ve got Fortune 500 quality consultants calling the shots. They know how to go after the kids that are most susceptible.”

Since the draft was eliminated in 1973 the military has drastically changed its recruiting approach. Ensign writes that Pentagon spending on recruiters and advertisements has risen sharply over the last five years, bringing the bill close to $3 billion a year. The military must bring in about 200,000 new recruits every year to replace soldiers leaving duty.

“Once you decide the military is going to be all-volunteer, anything goes,” Ensign said.

“Recruiters are now using bonus systems and profilers to help them out,” Ensign said. “And for being in such an unpopular war, I’d say the military is doing a good job of reeling in these kids.”

And some young people think the military is a good option for them. Today, joining the military gives soldiers more perks than in previous decades. The Army offers money for education, health care, vacation time, family services and cash allowances to cover the cost of living, according to goarmy.com an Army Web site. Paying for a college education is also a big bonus for prospective recruits. Depending on the soldier’s enlistment period, the Army can help pay up to $72,900 in education expenses. The Army also offers classes to active duty and reserve soldiers through online universities and learning facilities in Army posts.

Corporal Curtis Harding, who enlisted in the Marines after high school, said every person should have the freedom to make their own choices.

“Parents should take a step back,” Harding said. “Everyone always wants to tell you what to do, but in the end it is really up to the individual to decide about where they want to go in their own life. And in the military the worst that can happen is that you don’t like it, so at that point you can just leave. It’s simple.”

Â

Cops In High Schools

My school dean and a stern male security guard escorted my friend and me to an empty classroom near the dean's office, then ordered us to put our bags against the wall and stand in the middle of the room. The dean checked our bags, opening every pocket, looking through my folders, checking my wallet and cell phone. The guard asked us to turn out our pockets. Then he frisked us. That was the first time I was ever frisked. It felt like I was under arrest and they were about to read me my rights.

But the dean said they would let us go, since they didn't find anything, but they would still tell our parents what we had done. What we had done was retrieve my schoolbag bag from my friend's car, a block from the school, immediately after gym class -- returning to school on time, but a few moments after everybody else.

After that experience, I was not surprised to learn that some people are questioning the so-called security measures being used in what are known as Impact high schools around the city -- schools singled out for their high levels of violence, disorderly behavior or crime. I do not even go to an Impact school, and yet I was made to feel like a criminal.

Things are reportedly even worse in the Impact schools. The Impact schools safety initiative was created in 2004 by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the Department of Education and the New York City Police Department, to make schools safer. The program brought surveillance cameras, metal detectors and large numbers of uniformed and armed police officers to those schools. They started a zero tolerance policy where even minor incidents like disorderly behavior could be punished severely. The idea was that small crimes can lead to big crimes if they are not addressed quickly. Schools that improved would be taken off the list and have the security measures reduced. So far, 24 schools have been put on the list and 15 have been removed.

According to the Department of Education, the program is working. In a press release from last April, the department said that overall crime has gone down 33 percent and major crime has gone down 59 percent at Impact schools.

But not everyone is happy with the program. New York University's Wagner School of Public Service recently released a study looking at whether the Impact schools initiative is an appropriate approach to creating safe school environments. During the 2005-2006 school year, a team of NYU graduate students researched the initiative and interviewed leaders in the education system and the community. They concluded that while the Impact approach is effective, it is not appropriate.

They found that though police officers in schools are effective in the short-term, they hurt schools in the long-run. The report suggests that the presence of cops dares some students to commit crime and makes the rest of students feel threatened, as I did. The report also points out that Impact schools tend to be underfunded and overcrowded, and that might be part of the reason there is so much crime in these schools. It recommended that city officials focus on reducing over-crowding and increasing funding instead of law enforcement and severe punishment. The report also recommended that the city government and the education department should focus on treatment rather than punishment by hiring psychologists and guidance counselors for schools instead of police officers.

So while the education department was congratulating itself for getting crime down in schools, the study from New York University's Wagner School of Public Service was warning that the way they were doing it was going to have unsavory consequences in the long run. So I decided to interview a couple of students who attend Impact schools to see what they thought.

Jescine Jarvis, 15, is a sophomore at Harry S. Truman HS, an Impact school in the Bronx. Her school has metal detectors, security cameras on every floor, and a police presence.

"I've thought about how I would feel without the police there, and I would be scared," said Jescine. "I feel safe whenever I see them as I walk down the hallway or outside the school."

Jescine said the cops have arrested a few students, but she is not afraid of the police. She said students often joke around with the cops as though they're friends. "It helps me to see uniformed officers in schools. It's like seeing a uniformed police officer at the carnival or at a parade." said Jescine. "[It] makes me feel as if nothing can go wrong, and that if something does go wrong, then they'll fix it." Jescine agreed with the Department of Education report that police presence in schools was working.

A student at an Impact school in Queens, who asked to remain anonymous, also felt the police at her school was preventing crime, but felt the means did not justify the end. Six cops were stationed on each floor of her school for a year and a half. They were supposed to spread out, but she said that they just stood together and stared at students who walked by. "You don't want to look at them because you don't want them to say anything to you," she said. "We felt like criminals. It made me uncomfortable."

There were a lot of fights before the school was named an Impact school, and that after the cops came, "basically all the fights stopped and there was a lot less theft," she said. She thinks the cops' presence at her school did help reduce crime, but not because of anything they did; she never saw them do anything in the school. She thinks the school became safer simply because being labeled an Impact school made everyone pull together to improve the school and get rid of that label.

Like the NYU report, she believes that prevention would probably have been a better solution to the school's safety problems.

This article by Ilya Arbit, 17, a writer for New Youth Connections, is adapted from the pages of our partner, Youth Communication. Â

Small Schools Exclude Many Immigrants

In recent years, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Schools Chancellor Joel Klein have undertaken a wide range of school reform efforts, the cornerstone of which has been the dismantling of large, failing high schools and the creation of nearly 200 new small high schools to replace them. Designed to offer a more rigorous and engaging curriculum, these schools are yielding improved outcomes for all students, according to preliminary data. But there is one group of students for whom small schools are not as beneficial as they could be – immigrants and students who are English-language learners (referred to as ELLs). That is because many small schools do not accept them.

It is the policy of the New York City Department of Education to allow a small school to exclude English-language learners (and special education students) during its first two years of operation. This is permitted, according to the department, so that the schools can build up the necessary infrastructure to provide the instructional services these students require.

But, as it turns out, many of the older small schools still do not offer programs for these students, according to a new report issued by The New York Immigration Coalition (the organization for which we work), Advocates for Children, and seven immigrant community-based organizations.

Of the 53 schools surveyed that pre-dated the launch of Mayor Bloomberg’s small schools initiative in 2003, 21 offered no programs at all for English-language learners, even though they are legally mandated.

Overall, more than half of the 183 small high schools we looked at in the report had no such students at all or less than five percent in their student body; English-language learners make up more than 11 percent of overall high school student population in New York City.

Less Than Full Access

The Department of Education maintains that English-language learners are adequately represented in small schools, and opportunities have increased each year. There are eight new high schools specifically focused on such students. There are incentive grants to schools to improve enrollment of these students and provide services to them. The result of these efforts is that such students constitute more than ten percent of students in small schools, or just about one percent below their percentage in all public high schools in the city.

But the statistic can be misleading. Most of the students are concentrated in a few small high schools or relegated to large schools that might not be prepared to serve them. While most schools that were created to help these students, such as the International High Schools, are highly regarded, critics say they are not a substitute for full access to all small schools, many of which feature unique career-oriented and specialized programs.

The lack of full access to small high schools is troubling, say critics, both because of the equity issues involved and because this particular student population faces the greatest risk of educational failure. More than half of English-language learners drop out of high school over the course of seven years, compared with less than a third of the general high school population.

Yet, many such students who are at failing schools that are being phased out simply wind up at other large schools. For example, Theodore Roosevelt High School in the Bronx, which is being phased out, saw an 87 percent decrease of its English-language learners over four years. In those same four years, two neighboring large schools saw increases of 27 percent and 48 percent.

Geography and Outreach

The borough of Queens has the fastest-growing immigrant student population, and not surprisingly, the highest number of high school students learning English – nearly 11,000, or almost of a third of all such students throughout the city. Yet, in 2005, only seven percent of new small schools were located in Queens.

The fact that large sections of Queens are not served by public transportation, coupled with the fact that school choice is often driven by proximity to a child’s home, underscore the need to create more small schools in Queens.

Our study also identified barriers in the high school admissions and enrollment process that exacerbated the already unequal access to small schools. Only 25 percent of parents who responded to our survey reported receiving information about high school fairs from the Department of Education, even though these fairs are the centerpiece of the department’s efforts to inform and move tens of thousands of students through the high school selection process. Sixty percent of parents who responded to our survey reported not receiving any information about ELL programs when attempting to find appropriate high school placements for their children.

The report findings were based on data from the New York City Department of Education and the State Education Department, surveys of 1,155 parents and students from 72 schools, 12 focus groups with 109 participants, and interviews with senior staff in 126 small schools.

Deycy Avitia is education policy associate, and Norman Eng is communications coordinator, with The New York Immigration Coalition.

See the rest of this month's The Citizen.Â

The Last Word in School Funding?

If Governor George Pataki needs a motto to hang above the mantle in his new home on Lake Champlain, he could consider "Haste Makes Waste." Education advocates might prefer, "Justice Delayed is Justice Denied."

During his 12 years in office, the outgoing governor tried to block legal efforts to get more funding for the city's public schools. He fought the suit brought by education advocates, and when the courts ordered the state to provide billions more in funding, he refused to comply, going back to the courts again.

Last week, Pataki's maneuvers paid off for him. In what many believe will be the final legal decision on the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit, the state's highest court -- a court shaped by George Pataki--ruled that students do have a constitutional right to a decent education. But, in a victory for the governor, it set the price tag for this at an additional $1.93 billion. While this is, as one CFE lawyer put it "not pocket change," it is far less than the $6 billion sought by many school advocates and less than Pataki himself had once proposed. (For the court's decision and the dissenting opinion, click here.)

With Pataki about to leave office, many observers believe the chief beneficiary of the way he handled the case will be Governor-elect Eliot Spitzer, who will not be forced to provide as much as $8 billion more for schools across the state while at the same time keeping to his pledge not to increase taxes. Spitzer will, though, be under intense pressure from the Campaign for Fiscal Equity and other groups, such as the Alliance for Quality Education. They have vowed to fight for the $4 billion to $6 billion in additional funds they think the city needs to reduce class size, improve teacher training, expand pre-kindergarten programs and ensure that all students graduate.

WHAT THE COURT SAID

In its ruling, a majority of the Court of Appeals said some things that cheered the coalition of education advocates who had brought the suit. The decision reiterated earlier rulings that there is a link between funding for schools and the schools' ability to provide a good education. The court established the right to a sound basic education in its decision, according to Michael Rebell of the Campaign For Fiscal Equity. "Whatever the dollar amount, there's a constitutional obligation, and it's a permanent obligation," he said. "These are not minor things."

On the money, though, the court ruled that in calling for as much as $5.63 billion in additional funding, the lower courts had overstepped their bounds. "The role of the courts," Judge Eugene Piggott wrote in the decision, "is not to determine the best way to calculate the cost of a sound basic education in New York City schools, but to determine whether the state's proposed calculation of that cost is rational." Faced with a number of figures, the court adopted the lowest proposal: the $1.9 billion.

CHRONOLOGY OF THE CASE

|

This money, adjusted for inflation and with a few reductions from some increases in aid over the past few years, would come on top of the New York City Department of Education's current budget of more than $14 billion. About $6 billion of that now comes from the state.

The $1.9 billion figure came from the Zarb commission, a panel appointed by Pataki after the 2003 Court of Appeals ruling that city schools needed more money.

The commission hired Standard and Poor's to devise a way to determine how much more money New York City schools should get. The firm came up with a formula that looked at spending in successful school districts, added additional money for disabled, economically disadvantaged and non-English speaking students and considered the cost of living. Based on this, the commission determined city schools needed an additional $1.9 billion to meet their obligations.

Aspects of the formula have produced controversy. Standard and Poor's ranked all the districts according to expenditures and decided not to consider those in the top half, because, Piggott said in his ruling "not all successful schools operate in a manner that is economical."

In her dissent, Judge Judith Kaye, with the concurrence of Judge Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick, called the decision to exclude 50 percent of districts "wholly arbitrary." And she noted it eliminated districts in Westchester and Nassau which border New York City and whose schools have a number of similarities with the city's.

The state can increase the $1.9 billion, the court said, but that remains the job of the governor and the legislature. "The legislative and executive branches of government are in a far better position than the judiciary to determine funding needs throughout the state and priorities for the allocation of state resources," Piggott wrote.

But Kaye said the courts had had no choice but to step in. "There is no state budget plan for bringing the schools into constitutional compliance," she wrote. "That is precisely the problem."

The court abandoned an earlier ruling that the state government institute a five-year $9 billion capital plan for school construction and physical improvements because the Bloomberg administration and the state government have already agreed on and implemented a plan to build new schools.

And the court majority dismissed calls for new accountability measures to monitor the city Department of Education's use of the additional state money. "A new and costly layer of city bureaucracy is not constitutionally required," Piggott wrote.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg cheered this aspect of the ruling , saying he was "very gratified that the state's highest court has recognized all of the progress we have achieved and agreed with the city's argument that our schools don't need new state oversight and management."

Whatever the merits of the legal arguments by both sides, the decision may reflect changes on the court. Pataki appointed all four judges who were in the majority in the ruling, and Piggott, who wrote the decision, assumed the bench just in October of this year. His predecessor, Mario Cuomo, appointed the two dissenters, Kaye and Ciparick. (A fifth Pataki appointee, Victoria Graffeo, recused herself because she served as state solicitor general during some of the litigation on the case.)

A court "jam-packed with Pataki appointees... lacking the courage of its convictions... issued the legal equivalent of 'never mind,'" refusing to take on the governor and the legislature, the Daily News protested.

But other saw it differently. "In one of his more beneficial legacies, Pataki stocked New York's highest court with judges who were unwilling to micromanage policy," cheered E.J. McMahon.

WHAT THE COURT DIDN'T SAY

As has been the case in previous decisions, the court did not address some issues.

Deadlines: It did not, for example, set a date by which the schools have to get the money. In a press conference following the decision, Geri Palast, executive director of CFE, said she expected the money would be provided in Spitzer's budget for the 2007 fiscal year, which he issues early in 2007. Assuming the legislature meets its obligation to approve a budget by April, the funds would be in place when schools open in September 2007. That may make sense but is not addressed in the court ruling.

Who Pays: The court, as other courts have done, did not rule on whether the state government had to provide all the money or whether it could share the burden with City Hall. When the likely hike was pegged at $4 billion to $6 billion, many officials said the city would have to pick up about 25 percent of the cost. Bloomberg has steadfastly resisted this idea.

With the number far lower, there may be less pressure on City Hall to up its contribution. And Bloomberg tried to bolster that, saying "New York City has already increased the amount we spend for schools by $3.5 billion a year...We now look forward to receiving additional funds from the state."

The rest of the state: The court also said nothing about funding for other cash starved districts. The same calculations that came up with the $1.9 billion would result in approximately $500 million more to be divided among needy districts in the rest of the state, but this is not spelled out.

The funding formula: And the court did not discuss the state's funding formula for education. This complicated calculation, which Pataki has called a dinosaur, defies comprehension and protects many suburban districts, preserving funding even in the face of declining enrollments.

WHAT NEXT?

For many of those seeking more money for schools, the new ruling presents a clear disappointment. If the money is phased in over three to four years -- something the court did not preclude -- the total figure "would be much closer to the amounts by which the state and city have been increasing school funding in recent years anyway," wrote David Shaffer of the Business Council of New York State.

The $2 billion for city schools instead of $6 billion or more, "means lower test scores, it means children who can't read; it means children who can't do math; it means more children don't graduate," said Joseph Wayland, counsel for CFE.

City Councilmember Robert Jackson, who helped bring the suit in the early 1990s, was especially critical. Calling $1.9 billion a "Band-Aid solution," he said in a statement that the decision represented "an outrageous response to evidence that was upheld through multiple appeals and 13 years of struggle."

Other critics maintain there is little connection between money for schools and achievement in schools. Increasing school spending, they say, will boost taxes without producing better-educated New Yorkers." The tragedy of CFE," the Sun argued in an editorial "is that not one dollar of the money the taxpayers are going to be forced, against their will, to pay over to the schools is going to benefit the children who are forced by law to attend these schools."

And so, while the legal fight appears over for now, the political battle may have just begun. CFE and other advocates promptly called for Spitzer to make good on his plan to provide at least an additional $4 billion for city schools.

"Governor-elect Spitzer has said that when it comes to public education, he is seeking excellence not mere competence and efficiency," Palast said in a statement. "I am confident that through negotiation with the new governor and the legislature, our elected leaders will come through with the right amount of funding, combined with strong accountability measures, and finally deliver for our kids."

But Spitzer would not commit to any figure. He did say, "We must provide more money than this constitutional minimum. The executive budget I submit in February will propose significant additional funding on a statewide basis."

However much Spitzer decides to press for, he needs the approval of the legislature to make it a reality. The Assembly has generally supported more money for city schools, but the Senate, where upstate and suburban Republicans hold sway, has balked.

While the ruling creates a bit of a quandary for Spitzer, who as attorney general had to defend Pataki's position in court, most observers consider it a victory for him. "He gains a lot more maneuvering room in putting together his budget," wrote Bill Hammond on the Daily Politics. "If he does come up with $4 billion or more for the New York City kids, he'll get credit for showing leadership on education, not merely following a court order."

Spitzer also must decide where that money should come from. Even when he thought he was looking at an $8 billion additional bill for education statewide, Spitzer said he would not increase taxes. But critics of more school spending have long said it would necessitate tax hikes. A smaller settlement makes it easier to find the money.

WHERE WILL IT GO

Parents, teachers and school administrators have such a long wish list for the public schools that it seemed $6 billion would barely cover it, let alone $2 billion. The Bloomberg administration set out its ideas in a report to the court in 2004, and City Council last year released its own plan, drafted by a committee chaired by former District 2 Schools Superintendent Anthony Alvarado.

Parents, teachers and school administrators have such a long wish list for the public schools that it seemed $6 billion would barely cover it, let alone $2 billion. The Bloomberg administration set out its ideas in a report to the court in 2004, and City Council last year released its own plan, drafted by a committee chaired by former District 2 Schools Superintendent Anthony Alvarado.

Here are some of the possibilities:

Smaller Class Size

The City Council committee, the teachers union, and a number of city politicians have urged that a significant chunk of the CFE money go reducing to the number of students in city classrooms, particularly in the elementary school grades. They argue that classes in the city are bigger than those in much of the rest of the state and that no single reform would do more to boost student achievement.

While calling the court's ruling "extremely disappointing," Leonie Haimson of classsizematters.org Class Size Matters said that if a "significant share" of the $1.9 billion went toward bringing down the number of students in each city classroom it would probably "be sufficient."

In general, while the administration has said it has reduced class size, it has not made it a priority. The Bloomberg administration's proposal for the CFE money did not include any major proposal to cut class size, and audits by the state comptroller have found that the Department of Education did not use state money aimed at reducing class size for that purpose.

Expanded Pre-K

In its plan, the Bloomberg administration called for a new half-day program for three-year-olds, expanding pre-k programs for four-year old to a full day. Most education advocates would endorse such a plan. But CFE counsel Wayland notes that the $1.9 billion was based on spending only for grades kindergarten through 12 and so could preclude spending the money for pre-K.

Improving High Schools

There is general agreement that some of the additional funding should go toward improving the low high school graduation rate in city schools. In its plan, the Bloomberg administration stressed its proposals for more charter schools in the city and for continuing and increasing effort to replace large failing high schools with small schools. While a number of such schools already exist, many still need permanent homes, and there is concern over their long-term survival after money from the Gates Foundation and other outside sources runs out.

Others have suggested that the Department of Education use some of the funds to create good vocational programs that could encourage students who are not college bound to remain in high school.

Better Teacher Training and Pay

Most proposals call for some efforts to recruit and keep qualified teachers in the school system. The Bloomberg plan calls for new career advancement programs, merit pay and recruitment programs. The council report recommends higher salaries for teachers in low performing schools and new assessment measures.

Even without the CFE money, though, teacher salaries are slated to go up, under a new contract agreement (still to be ratified) reached between the uft.org United Federation of Teachers and City Hall. The contract appears to abandon efforts to exact productivity gains to pay for the raises, and the money for them would come out of general city revenues.

Other proposals call for spending some of the money on special education and instruction for non-English speakers.

Having some $4 billion less to spend than school officials had hoped for will force the Bloomberg administration to make some tough choices on education. "In terms of priorities, universal prekindergarten along with funding lead teachers in math and science in our high-needs schools are at the top of the list,” Schools Chancellor Joel Klein said in a written statement to the New York Times.

But Joseph Viteritti, a professor of public policy at Hunter College, told the Times he was afraid the Department of Education might use any reduction in the CFE settlement as an excuse for problems in the schools. "People inside the system will always have the impression that they didn’t get enough, they didn’t get what they deserved and if we only had more,” he has said. “That’s always going to be there as a kind of alibi.”

However much additional money comes to the city, some parent groups and others have expressed concern about how any spending decisions would be made. Class Size Matters has called for an array of accountability measures including review by state officials and City Council approval of a spending plan. "Everybody ... feels that under mayoral control, there's been even less accountability and transparency than before," said Haimson.

Even as the CFE legal fight may be winding down, another legal action continues. A group of school districts in small cities elsewhere in the state have brought a suit challenging their funding from Albany. Although a judge dismissed the action this summer, the districts say they will press their case. Other similar challenges seem inevitable.

Â

Special Ed: Needs Improvement

To Chris Schwabenbauer, getting an education for her autistic son is a matter of basic rights. So she became irate when a principal of his host school barred autistic youngsters from using the main bathrooms on days when the general school population was taking standardized tests.

"It's a civil rights issue," Schwabenauer, a PTA president, said. "I'll put up with it soon as you start hanging up the black and white signs over the water fountains again."

Now, that principal is gone, the city has said it will not tolerate such behavior, and Schwabenauer has nothing but praise for the education her 10-year-old is getting at P.S. 255, a special-education school in various school buildings around Queens.

"You can't ask for anything more," said another P.S. 255 parent, Victor Ty. "It's amazing."

The Department of Education says that improvements are taking place throughout the city's programs for students with disabilities.

But last week the state Department of Education said much more needs to be done. It found that all of the city's 33 schools districts are failing to meet the needs of special education students and that 23 of them require "immediate intervention" to address low test scores and woeful high school graduation rates. Only 37 percent of all special education high school students in New York State graduate. But in New York City the number is far worse: Less than 17 percent of special education students receive regular diplomas.

"Students with disabilities can and do succeed in many schools throughout the state," education commissioner Richard Mills said. "But in other schools, their performance is very low."

The state's report comes as the city faces a civil rights complaint charging it discriminates against special education teens and at least one major lawsuit over its special education programs.

The city's education department says it has already moved to address problems and has made progress. "We have moved aggressively to make improvements," Linda Wernikoff, the deputy superintendent for special education, told a City Council hearing last month.

NEW YORK'S PROGRAM