|

|

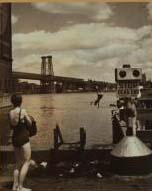

If you happen to fall in to the New York Harbor, the Hudson, the East River, or Jamaica Bay, you need not fear bacterial infections or diseases from industrial pollution, according to a draft of a yearly report from the city's Department of Environmental Protection. Unless you fall in after a storm.

In fact, despite their sullied reputation, the quality of most of the waters around New York City has been pretty good in recent years. Since passage of the nation's Clean Water Act of 1972 and improvements in the city's handling of sewage in the 1980s, city waterways have improved. Perfection is a long way off. But for a city that disposes of 1.9 billion gallons per day from wastewater treatment plants in New York waters (in 2003) and lives with the effects of pollution from years gone by (such as PCBs dumped upriver in the Hudson), the waters are relatively clean.

"During the last two decades, water quality in New York Harbor has improved to the point that the waters are now commonly utilized for recreation and commerce throughout the year," says the Department of Environmental Protection’s draft report. Charles Strucken of the department says they are still working on the final report about New York water quality (not drinking water).

One problem that continues to plague the waterways stems from storm water and sewage being combined. When it rains, the pipes and water treatment facilities can't handle all of the waste. Sewage is sometimes discharged directly into the waters.

The storm runoff also brings pollutants from the land and streets, such as motor oil, pet waste and pesticides, says Maureen Dolan of the Citizens Campaign for the Environment.

In anticipation of the sewage discharges, the city closes beaches even before storms. In the summer of 2004, she reports, 12 beaches were closed, for a total of more than 400 days. The Bronx experienced the most with 289 beach closure days for eight beaches. Dolan expects similar figures for 2005 (results have not yet been tallied). The technology is there to keep the sewage out of the waterways. "In 2005 we should not have sewage flowing into the beaches," says Dolan.

IMPROVEMENTS

"Right now looking out my window, I can see down a depth of eight feet," says Dan Mundy, founder of Jamaica Bay EcoWatchers. He became active in the mid-1990s, when he saw conditions in the bay where he lives deteriorating. Since then, the waters have improved. Though 300 million gallons a day of treated sewage water comes into the closed estuary adjacent to JFK Airport, Jamaica Bay is holding its own, says Mundy. "The bay is swimmable. Fishing is great."

Swimming and fishing are all right in the Hudson and East Rivers, too. "The water is cleaner now than it was ten years ago -- and by some estimates 100 years ago. It is perfectly safe and sanitary to swim in it," says the Manhattan Island Foundation, which sponsors an annual swim around Manhattan.

Don Riepe, Jamaica Bay Guardian for the American Littoral Society, which looks after shorelines , says eating fish such as striped bass, bluefish and other game species from the waterways is generally safe. Because of pollutants that rest on the bottom, he recommends staying away from bottom feeders. "Things like American eels that live in the bottom of the bay you don't want to eat. You don't want to eat shellfish. Everything else, use common sense. Don't eat a lot, and make sure it's cleaned properly." He recommends taking off the skin and fat layer because that's where "pesticides and heavy metal accumulate."

"Floatables" (Litter And Debris)

Waterways around New York generally look better this year, reports Barbara Cohen, New York Beach Cleanup Coordinator for the American Littoral Society, which sponsors a statewide beach cleanup day each September. Volunteers collected 73,408 pounds of debris around Manhattan alone last year. Though figures haven't been compiled yet for the 2005 cleanup, Cohen says that this year "beaches seem to be cleaner than in the past."

The debris, what those in waste treatment call "floatables," contributes to the look and to the physical well-being of waterways. "The main source of floatables is street litter, which ends up in the city's storm drains (catch basins) and sewers," reports the city's environmental department Web site. Plastic accounts for 42 percent, paper and polystyrene for some 26 percent apiece.

"In New York, cigarettes, caps and lids, and food wrappers accounted for nearly half of all the debris items collected," reports the American Littoral Society about their 2004 cleanup.

Debris is a problem for the small waterways, too. In the cleanup this year, Cohen says, "Coney Island Creek is a bad area in terms of litter and other debris."

Debris is one of the Harlem River's problems as well, but as a tributary of the Hudson, it also suffers from the same PCB contamination that the Hudson does, reports the Institute for Civil Infrastructure Systems at New York University's Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service.

POLLUTION PERSISTS

The worst problem for the tributaries and "small embayments" are bacteria from the storm runoffs, says the Department of Environmental Protection's draft report. "Some of these tributaries are the only remaining areas where bacterial counts exceed standards on a regular basis."

The report details pollution from industry and storm water discharge in Newton Creek, which marks the border between Queens and Brooklyn and flows into the East River. Improvements to the creek are scheduled for completion in 2007.

The infamous Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn remains polluted and even smelly at times for the same reason, reports Crain's New York Business. Developers who want to build housing along the canal are reportedly daunted by the city's recent postponement of the canal's cleanup.

|

|

The Bronx River also faces storm runoff that pollutes other New York City waterways. That's a problem for Jamaica Bay, too. There are still algae blooms on occasion, caused by an excess of nitrogen from the runoffs. When the algae die, it sucks oxygen out of the water, and fish leave or die. "The bay is also losing 50 acres of marshland a year, and no one has figured out why so far," Mundy says. Shell fishing is still prohibited.

Still, Mundy says in the past four years, he has become optimistic. The Department of Environmental Protection is building huge holding tanks to handle the overflow. They are spending hundreds of millions of dollars on capital projects.

Mundy and others who have watched the water for a long time are convinced that the beauty of New York's rivers and harbors is not just on the surface.

Related Articles

The Waters of the Harborby Peter Fleischer, about the Department of Environmental Protection's 2002 water quality report.

Earth Day by Eric Goldstein, including a look at the waterways.

Congress Acts to Protect New York's Water by Congressman Ed Towns, about state water table legislation (for drinking water)

Â