New York City Council STATED MEETING - December 3, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - December 3, 2003

Quote of the Day:

"Nothing threatens the quality of life on Staten Island more than the reckless, unplanned overdevelopment that we have experienced over the last 25 years." - Councilmember Andrew Lanza, voting in favor of a major overhaul of the zoning laws in Staten Island.

Meeting Summary:

On December 3, the New York City Council unanimously approved a major rezoning for nearly half of the residential neighborhoods in Staten Island. The plan aims to preserve the borough's "suburban neighborhood character" by slowing housing construction, limiting the number of apartment buildings that can be built, and protecting open space, yards, and trees.

The legislation was submitted by Staten Island Borough President James Molinaro and a task force appointed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg to address issues of overdevelopment pushed the plan through the city's process in less than four months. (Read the full press release from the mayor's office.)

The population of Staten Island has increased 20 percent since 1990 and, with a growing demand for housing, officials say many single-family homes have been torn down and multiple unit apartment buildings have been put in their place.

"The rules that govern building... are outdated, antiquated, and ineffective," said Staten Island Councilmember James Oddo. "When you see these homes being torn down, you have to do something."

The zoning changes will affect 40 percent of the borough's residential neighborhoods. They also:

- Require space between buildings

- Mandate the size of the yard around a house

- Require that trees be planted in new developments

- Limit the height of additions built onto the top of houses

- Require adequate parking in the area

- And restrict the building of private roads.

The zoning changes passed by a vote of 48 to 0 and will take effect immediately.

Some council members from other neighborhoods, particularly Queens, are hoping that similar zoning reform will occur elsewhere in the city.

"This shows a commitment to preserve our neighborhoods and their characteristics," said Queens Councilmember Melinda Katz, who chairs the land use committee.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for December 11.

For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.

Cell Phones: New Developments

On a recent Friday, I stood, shivering, on the dimly-lit corner of 116th and Broadway trying to call my friend on my new Sprint cell phone. As if dialing numbers on the tiny keyboard with winter gloves was not enough of an inconvenience, I found that the Sprint network was unavailable and that my phone was in "roaming" mode - looking for another network to place the call.

I dialed the number, waited a few seconds, and just when I thought that my friend's phone was ringing, I got a message from Verizon - was that James Earl Jones? -- saying that their network could not identify my phone. So, there I was, on my way to a party, but stuck in one of the city's many "dead zones".

One week later, I finally got around to reporting the problem on a short survey remembering Mayor Michael Bloomberg's announcement that the city is using the 311 non-emergency number and the nyc.gov Web site to collect and map information about these "dead spots."

In New York, mobility is not just a luxury, it is a way of life. And, many New Yorkers have come to rely on using cell phones to manage their lives, sometimes even canceling their land-lines in favor of their mobile.

By 2005, more time will be spent on cell phones than on land lines in New York according to data from Senator Chuck Schumer. This is true even when considering the large number of calls made in New York City, the world's biggest telecommunications market. In the next three years, the number of minutes of cell phone calls made in New York State is projected to increase 37 percent (66.7 billion to 106.2 billion) while the number of minutes of land line calls is projected to decrease 8.4 percent (106.2 billion to 98.0 billion).

Thus, poor reception quality and lack of cell phone coverage, is not merely an inconvenience, it is also a matter of public safety. Increasingly 911 phone calls are being placed on cell phones. According to Commissioner Gino Menchini, of the Department of Information, Technology and Telecommunications (DoITT), "in certain circumstances, cell phone dead zones create a hazardous condition for New Yorkers. We hope the cell carriers will use this information to improve the quality of their service for the good of their customers and the city."

KEEPING YOUR PHONE NUMBER

The city plans to make the results of its cell phone survey public on nyc.gov on the same day that a new federal policy (PDF file) goes into effect in the nation's top 100 metropolitan areas that allows consumers to switch wireless providers without having to give up their phone number.

In the past, many cell phone customers have been dissuaded from switching providers because they consider their phone number to be part of their mobile identity. Freelancers, consultants and small business owners rely on having a number where they can be reached anytime in order to keep in-touch with their clients.

In addition, the Federal Communications Commission ruling allows customers to change their home wire-line phone number into a cell phone number. According to The New York Times, industry analysts estimate that three percent to seven percent of telephone users in the United States - or 4.5 million to 10.5 million people - no longer have traditional land-lines and rely on cellphone services exclusively.

However, given the telecommunications failures of 9/11 and Blackout 2003, New Yorkers might want to think twice about taking their home number with them, at least until more reliable emergency communications have been implemented.

The city is also trying to make sure that wireless providers follow their own best practices, which were announced in September. Some of these include allowing for a 14-day trial period for new service and making service maps available at stores and on company Web sites.

Mayor Bloomberg's initiative shows support for this new federal policy and sends a positive signal to the wireless providers that serve New York City. The city can help providers improve their service but, in the end, if customers aren't satisfied, they can always switch providers.

For years, wireless providers have been lobbying in Washington to prevent the implementation of this law which was part of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. This is because customers already switch cell phone providers more often than they change companies in other types of services. This is called the "churn rate".

The new federal policy however, comes with a few caveats. Wireless carriers may charge customers a fee to move their phone number to another carrier. Getting a new phone also means having to re-enter hundreds of names and numbers into the address book of their new phones.

Since companies use different technologies, it is likely that customers will have to replace their phones. For example, an AT&T phone will not work on a Sprint network, and a Sprint phone won't work on a T-mobile network. Thus, many more cell phones will be dumped at landfills where they will be "leaking toxic metals and chemicals into the ground" according to the Associated Press. About 100 million cell phones are thrown out each year in the United States.

On November 19, Senator Chuck Schumer warned New Yorkers not to sign new long-term contracts with their cell phone providers because they won't be able to take advantage of better deals which will be offered after November 24th. Many companies including AT&T, Cingular and Sprint have been pushing to enroll customers before the new policy goes into effect. The new policy will promote competition among carriers which will lead to lower prices and incentives for companies to improve their coverage.

The Federal Communications Commission expects six million of the 150 million cell phone subscribers nationwide to switch providers within the first seven days of the new policy. But, only 42 percent of wireless customers nationwide know about the new policy according to telecom consultancy The Management Network Group as reported by The Washington Post. Thus, the city's efforts to make this information more easily accessible to the public should be applauded.

I don't know about you, but after my experience standing in the cold in a "dead zone" on Broadway, I'm certainly going to re-evaluate my cell phone provider once the new federal policy goes into effect.

Laura Forlano is a doctoral student studying communication technology policy at Columbia University.

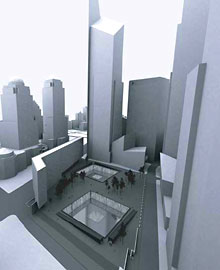

The Eight 9/11 Memorial Designs

World Trade Center leaseholder Larry Silverstein examining one of the design finalists.

Lyndon Harris was the priest in charge of St. Paul's Chapel when the World Trade Center was destroyed just a few yards away. His experience at Ground Zero, though, was not only one of loss. Now, more than two years later, he smiles as he recalls cooking hamburgers for rescue workers outside the church in the days after September 11. As the rescue effort continued, he said, more and more firefighters came to eat from his grill: "By the end of it, we were a four-star place."

That is why Father Harris had to admit last week that, while he was "just beginning to digest" the eight designs chosen as finalists in the competition for a 9/11 memorial at Ground Zero, he already felt somewhat disappointed that the designs don't reflect his own experience.

"They have a mood, a kind of a vibe, akin to a crypt," he said. "But they are not inspiring."

Father Harris was saying this a day after the designs were presented, as he sat in a small, windowless classroom at Pace University with about a dozen other participants in the latest series of workshops organized by Imagine New York to allow the public to respond. Within days, hundreds of New Yorkers had attended their workshops, and some 10,000 people had made comments on their web site. By early December, the group will submit a short report to the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, summarizing what it has heard.

It is surely too soon to proclaim a consensus, as many people are still feeling out what they think. But the group with Father Harris -- among them, family members of some who died on 9/11, Ground Zero rescue workers, and people whose designs were among the 5,193 not selected in the final eight -- had some strong reactions.

They talked about what they liked about the designs: All eight recognized each individual victim, provided a contemplative space away from the city, and made creative use of light. And they talked about what they didn't like: The final designs were too "corporate," too "architectural," they had too many "bells and whistles," they lacked a certain humanity.

This is not the first time the public has reacted strongly to plans for Ground Zero, of course. When the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation presented six plans for the site as a whole on July 16, 2002 -- all of them with titles that began with the word memorial (Memorial Square, Memorial Plaza, Memorial Promenade, etc.) -- they were overwhelmingly condemned by the public. Officials bowed to public opinion and held a new competition. On December 18th, nine new plans were presented, the public responded much more favorably, and on February 27th, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation and Port Authority officials selected the plan designed by Daniel Libeskind.

While Libeskind's overall design for the World Trade Center's replacement suggested where the memorial would go, there was a separate competition for the design of that memorial, which began last August. It included a public hearing, the drawing up of a mission statement, the selection of a "jury" of 13, and then an open competition that, officials say, was the largest of its kind in history.

After some five months of sifting and sorting through the 5,201 entries and deliberating in absolute secrecy, the jury selected the eight that were presented to the public on November 19th. It didn't take months, but more like minutes, for New Yorkers to begin to respond, including those in Father Harris' group at the Imagine New York workshop.

"There was a feeling that there was a huge potential," said Nikki Stern, who lost her husband on 9/11, summing up the views of the group, "but somehow something missed the mark."

DESIGN HIGHLIGHTS: LIGHT AND WATER

The 5,201 design entered the competition were bound by several guidelines:

- to acknowledge each individual who died, including all those who aided in rescue, recovery, and healing

- to create a space for reflection and contemplation

- to acknowledge the historical significance of 9/11 and encourage people to learn more

- to evolve over time

Besides their common goal to reflect these guidelines, the eight finalists also resemble one another in the use of two key elements - light and water.

LIGHT

When Kevin Rampe of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation introduced the eight chosen designs on Wednesday morning, he characterized them as the next stage in a process that began on September 11, 2001 with the first makeshift memorials -- the flowers, the first heartfelt messages tacked to traffic poles and bus shelters, "the first candles lit at Union Square Park."

Light was also the dominant element in the temporary memorial called the Tribute in Light, two beams of light shining up from Ground Zero every night for a month.

So it is perhaps not surprising that light plays a major role in many of the eight finalists. Three of them use the word "light" in their titles.

In Garden of Lights, natural light comes through holes in the ceiling of underground chambers to create 2,982 individual beams of light shining on 2,982 altars, one for each of the victims.

Inversion of Light includes a space on the northern footprint containing a representation of the floor plan of the towers, lit from underneath. A pool covers the southern footprint, with light shining from below the water. During cold weather, the vapor created by the heat from the light will appear as flames on the surface of the water.

Passages of Light also uses the sun to light a sunken area, through a glass canopy that covers a large part of the memorial site. Beams of light also extend upwards from the floor of this area, creating the effect of a "cloud" of light.

Votives in Suspension creates a room on each of the footprints, dimly lit by hanging candles, one for each of the victims. The candles are suspended over shallow pools at different heights indicating the relative ages of the victims.

WATER

Water is a major element in many recent memorials. The 9/11 memorial at the Pentagon creates small pools beneath the lighted benches that represent the victims. The Oklahoma City memorial contains a shallow reflecting pool of moving water, which is intended to be a place of quiet reflection. Many of the eight memorials for Ground Zero incorporate similar ideas.

Suspending Memory is the plan with the most water, measured by volume. It fills the site with a large pool. The two footprints of the towers act as islands within the pool, connected by a stone and glass bridge. On these tree-shaded islands, there are lighted glass columns, one for each victim.

Reflecting Absence is almost this plan in reverse. A plaza covers the site, with two sunken pools standing where the towers once stood. Around the perimeter of the pools are underground chambers with glass walls.

Lower Waters and Dual Memory also use both light and water, but in a more complex manner than the other six designs.

In Lower Waters, sheets of water fall from a pool on top of a granite building on the northern footprint. Across a slanted park which covers the entire site, an open plaza on the southern footprint has a wall listing the names of the victims, trees, benches, and the facade of a 9/11 museum.

In a semi-enclosed area on the northern footprint, Dual Memory sends falling water down sheets of glass on which there are portraits of the victims. On the roof of this area are 2,982 spots of light, one for each victim. Ninety-two sugar maple trees planted in a lowered plaza on the southern footprint represent each of the countries that lost a citizen on 9/11.

THE NAMES, THE BEDROCK

All eight designs list all 2,982 names. For some of the firefighters who attended the unveiling ceremony at the Winter Garden on Wednesday, one question took priority: How were the names listed?

"We want to make sure that the firemen and the police officers that were killed in 9/11 are listed together as a group under the heading of FDNY [with] a description of what they did if they came here to save lives and lost their own,"said Patrick McCarbill, one of several dozen firefighters with the Coalition of Fallen Heroes who attended the ceremony in bunker jackets.

The question of names has been a sensitive one, as some feel strongly that rescue workers should be honored by being listed together with ranks, and others are adamant about avoiding the hierarchy that such an action would create among the victims. As the program for the memorial process did not guide designers on this issue, there were several different approaches.

Two of the designs list rescue workers together. Inversion of Light organizes names into groups of civilians and non-civilians, while Passages of Light groups the names based on where the victims were at the time of their deaths: There is a distinct group of names for those who died in each tower, separated out by civilians and rescue workers.

One more, Suspending Memory, distinguishes firefighters and police officers with a bronze helmet on the glass pillars used to represent the individual victims.

The rest of the designs either avoid the issue altogether (at least for the moment), or list names alphabetically.

But while the Coalition of Fallen Heroes found at least something to approve of in some of the plans, the Coalition of 9/11 Families said that each of the plans deserved a grade of F, because they failed to preserve the footprints of the towers to the bedrock level, a depth of 70 feet. None do because the Libeskind design called for the footprints to descend just 30 feet below street level.

"ARCHITECTURAL FEATS, LACKING IN FEELING"

The competition was open and anonymous, which its organizers said would encourage diversity among its entrants. Indeed, designs came from 49 states and 62 countries foreign countries. But architects dominated the finalist field, a result, say critics, of stringent requirements that kept laypeople from competing effectively. The eight designs very much reflect the background of their authors.

This led many to criticize the designs as overdone, gimmicky, or sterile, impressive as architectural feats but lacking in emotion. Participants in the Imagine New York workshops voiced disapproval that, while the designers invented creative ways to bring new elements in, few did much to highlight the elements already there, or to bring back artifacts that were originally at the site - like the damaged globe currently located at Battery Park.

Form, some observed, seems to have taken precedence over feeling.

Herbert Muschamp, the architecture critic from the New York Times, wrote that most of the designs "offer an excess of spectacle...Everything here is wonderfully polished. Each finalist could be the winner in a dozen memorial competitions. But that is not really a compliment, is it?"

At the same time that the designs were criticized for having too much of an architectural bent, they were accused of lacking sufficient planning perspective to have them become part of lower Manhattan beyond the walls of the memorial site itself.

Justin Davidson wrote in Newsday that the designers want to "build 10-story barriers and buried bunkers, they would flood the site and create islands - anything to carve a massive mausoleum out of a vital city."

"They have light, air, water and greenery," wrote Joyce Purnick in the New York Times. "What the eight designs for the World Trade Center memorial do not have is a feeling of New York."

THE PUBLIC AND THE PROCESS

To some critics, the final memorial designs were bound to be disappointing - not so much because of the designs themselves, says architectural historian Max Page, but because of what he sees as "fundamental flaws in the process" of choosing them. (See Rethink The Type Of Memorial We Want.) To some, one of those flaws was the lack of public participation.

Officials from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation see it differently. They refer to the future memorial at Ground Zero as the "people's memorial," and regularly champion the amount of public participation that they have built into the kind of design competition that usually takes place entirely away from public scrutiny. In drafting the mission statement for the memorial, the competition's organizers solicited written responses from all those who lost family members on 9/11, held public forums, and consulted with its Family Advisory Council on what requirements to put into the competition.

Since that point, the jury has been operating out of the public eye, and will not be open to an official comment period before a final design is chosen. Indeed, the jury members and the finalists are forbidden from talking to the public, though officials of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation say the jury will take into account reactions at civic meetings such as the ones held by Imagine New York.

That is the reason why the eight finalists were made public at all, rather than simply waiting to announce the final winning design, according to Rick Bell, head of the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects "What is a two-stage process if not a chance for public discourse?"

Charles Wolf, a member of the Family Advisory Council, also believes that public opinion will filter back to the jury. But he thinks the jury should be the final arbiters. "Those who are shouting about the fact that they don't like this and they want to have that are a vocal minority. I respect their views, but I don't appreciate the fact that they are trying to preempt the jury process to advance their own views....A republic works better than a democracy in this case because you have a qualified representative to do it for you. The jury is our representative." (See Let The Memorial Jury Do Its Work.)

For the Coalition of 9/11 Families, this is not sufficient. To many of its members, an important element of the memorial has already been eliminated from consideration. The group has responded by looking outside the process for influence. In addition to sponsoring an online petition that calls for historic landmark status for the footprints of the towers, requiring that they be left untouched, the group has worked with Representatives Carolyn Maloney and Chistopher Shays to introduce a bill into Congress which would study whether the spots where the towers stood should be national landmarks.

Phil Craft, a spokesman for Maloney, sees the coalition's activities as a sign of a failure in the process of creating a memorial. "If the families are coming in droves [to complain]," he said, "then the question is, do they have a seat at the table?"

GOING FORWARD

The jury is expected to choose the winning design by January. Until then, the finalists will go into more depth. Funding, not an issue in the first stage, is now being considered, and designers have to draw up a budget for their designs. When the time comes, the project will be paid for through a foundation which is currently being established. Fundraising will begin in January, according to Governor George Pataki. There is also room for compromise and fine-tuning on the physical aspects of each plan.

Lyndon Harris of St. Paul's Chapel is optimistic that the final decision will be handled well, but he is still wary. The process is not over yet and the stakes, he observes, are high.

"Whatever statement we make is going to be read on a global scale," he said. "We have a great opportunity to do something great. We also have a great chance to screw up."

Also In This Series

The Eight Memorial Finalists

Rethink The Type Of Memorial We Want

The largest competition in the history of the world - to design a memorial to the victims of the terrorist attacks on 9/11 - has resulted in eight finalists that have provoked words such as "generic" and "impersonal," and, worst of all, "like an airport design." There were 5,201 entries from 63 nations and 49 states and yet we are left with proposals that fail to approach our hopes. What went wrong?

The criticisms of the memorial designs that are percolating up in conversation and in the press are, at first glance, not completely fair. Each of the designs offers some element that individuals may find deeply moving. Norman Lee and Michael Lewis's votive candles hanging above the foundations of the towers, each representing one of the 2, 982 victims who perished that day (and in the 1993 bombing), could move visitors and mourners the way the children's memorial by Moshe Safdie at the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem does. Dual Memory, by Brian Strawn and Karla Sierralta, makes permanent the powerful "Portraits in Grief," the brief biographies of the victims published in the New York Times in the year after 9/11, with projections of images and information about each victim. All of the designs are earnest, by talented young designers, and sure to provoke tears of mourning from many. But that is not the measure of success for a memorial.

The fault is not with the designers, but with the process. Everything about the rebuilding of Ground Zero, and the memorial in particular, has been rushed. With a Republican Governor and Mayor, there is only one date that mattered to the rebuilding process: the opening of the Republican convention in New York next August. The laying of the cornerstone for Liberty Tower and for the memorial has been preordained to occur when George Bush rolls into town.

But although some might like to blame it all on the Republican Party, there were even more fundamental flaws in the process. The focus of the program guidelines was on recognizing the individuals who perished, and not about how future Americans would understand 9/11 and might move forward. As a result the jury has chosen eight beautiful designs for a cemetery, but no designs for a living memorial to 9/11. Our obsession with building increasingly more clever, and complicated, memorials to remembering individuals who lost their lives in disasters has steered us far away from an older way of thinking about memorials, one that looked more toward a common future than to individual loss.

New York has distinguished itself from other cities by its lack of grand memorials. As architect James Sanders has noted, the greatest of our memorials - the Statue of Liberty - stands in the middle of the harbor and not at the end of a wide boulevard, or amidst a large square. New York's monuments have long had to compete for space on the grid, and against the city's restless physical renewals.

But New York is in fact filled with memorials of a different kind. All across New York City are places and institutions that ennoble us that are in fact memorials. John F. Kennedy High School, Lincoln Center, Father Fagan Square in Queens, McCarren Park Pool in Brooklyn. There are the branches of the public library built by Andrew Carnegie, hospital wings built by Sloan and Kettering, and public housing complexes named after Walt Whitman and Louis Armstrong.

True, these places do not try to memorialize New York's most horrific disasters (a small plaque marks the site of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire; a small tablet in Tompkins Square park is all that reminds us of the worst single loss of life in New York before 9/11, the General Slocum disaster of 1904). But shouldn't a human disaster of such great proportions ripple far beyond the four acres allotted in Ground Zero? Shouldn't there be signs of the way we are making the city better in these victims' honor all over the city? These are the kinds of memorials that dot New York City, as well as cities and towns across the country - public libraries, memorial concert halls, parks, scholarships, pools. But they are utterly absent from the group of finalists offered to us.

Missing from the group of finalists was the first public memorial to 9/11, which was also the most fleeting: the Tribute in Light, the towers of light shining up from Ground Zero, that were allowed to shine for only one month, and then went dark. The decision to turn off the lights was the best decision anyone has yet made, because it said to us all that the memorial to the dead is not our final destination, the city is. New York, our national jewel, what E.B. White called "the greatest human concentrate on earth, the poem whose magic is comprehensible to millions," is the lasting memorial.

Let's send the jury back to find among those 5,000 entries proposals that see the memorial as a chance to invest in what has always made New York great: not its private capital but its human capital, its people. That would be the unforgettable memorial.

Max Page, the author of The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900-1940, teaches architecture and history at the University of Massachusetts, and is curator of a forthcoming exhibition at the New-York Historical Society on the centennial of Times Square.

######

Also In This Series

• The Eight 9/11 Memorial Designs

• Rethink The Type Of Memorial We Want - by Max Page

• Let The Memorial Jury Do Its Work - by Charles G. Wolf

• We're Being Shut Out Of The Process - by Rosalen Tallon

The Eight Memorial Finalists

• Votives in Suspension (Norman Lee and Michael Lewis)

• Inversion of Light (Toshio Sasaki)

• Garden of Lights (Pierre David, Sean Corriel, Jessica Kmetovic)

• Suspending Memory (Joseph Karadin, Hsin-Yi Wu)

• Lower Waters (Bradley Campbell, Matthias Neumann)

• Dual Memory (Brian Stawn, Karla Sierralta)

• Passages of Light: The Memorial Cloud (bbc art + architecture)

• Reflecting Absence: A Memorial at the World Trade Center Site (Michael Arad)

Let The Memorial Jury Do Its Work

A lot of people who lost family members on 9/11 will have a hard time even coming to look at the memorial plans. I know when I saw the designs for the first time, I was emotionally overwhelmed. It's hard when you don't have a grave for your wife. There are thousands of us who have no graves for our loved ones.

The designs that I like the most are those that involve the use of light as their theme. I realized I like these because it's all about light vs. dark, good vs. evil. It was evil piloting those airplanes, yet at the moment they penetrated their target, good won. People helped people wherever they could; a doomed person on the 102nd floor helped and comforted another doomed person; firefighters, many times throwing caution to the wind and doing anything they could, rescued people; the people in my neighborhood in Greenwich Village comforted me for weeks on end after the disaster. This is how good won over evil.

I didn't view the memorial finalists looking for "item a" or "item b." I wanted to see the designs and let them talk to me. Then, I'll look to see what specific features they have, such as access to bedrock, etc.

When you walk into a memorial, especially this one, you should feel something, like when you walk into one of the great cathedrals of the world such as St. John the Divine here in New York or St. Paul's or Westminster Abby in London. You should not have to think. Thinking is for the museum. This is all about feeling. It's about spirituality.

I believe there are people who initially will be angry about whatever memorial they see. That's because they are still going through the grieving process, and everybody goes through that. But I do believe that when the memorial is finished, most of the people will come around and like it. Those who are shouting about the fact that they don't like this and they want to have that are a vocal minority. I respect their views, but I don't appreciate the fact that they are trying to preempt the jury process to advance their own views.

I've fought to be part of the process the Lower Manhattan Development has established. I'm better off if I'm part of it than if I just let what happens happen around me. The Family Advisory Council is a group of people that have been asked to advise the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. We respect each other, but we also have differences of opinion. And we have a say. Before I was on the Council, it drafted the Memorial Mission Statement and Program for the memorial competition, and only then did the jury select the designs.

I don't believe I'd be qualified to be on that jury.

I think the public should definitely voice their opinion, because I believe that it will filter back to the jury. But, there are lots of times the public is wrong about things. One of the definitions of a good leader is he sometimes has to take his people in a direction they don't know they need to go. And in a sense here, the jury has to be a leader. In that sense, a republic works better than a democracy: in this case because you have a qualified representative to do it for you. The jury is our representative.

Charles Wolf is a member of the Family Advisory Council to the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation which advises on rebuilding issues including the memorial process. His wife was killed on 9/11. This essay was adapted from an interview.

######

Also In This Series

• The Eight 9/11 Memorial Designs

• Rethink The Type Of Memorial We Want - by Max Page

• Let The Memorial Jury Do Its Work - by Charles G. Wolf

• We're Being Shut Out Of The Process - by Rosalen Tallon

The Eight Memorial Finalists

• Votives in Suspension (Norman Lee and Michael Lewis)

• Inversion of Light (Toshio Sasaki)

• Garden of Lights (Pierre David, Sean Corriel, Jessica Kmetovic)

• Suspending Memory (Joseph Karadin, Hsin-Yi Wu)

• Lower Waters (Bradley Campbell, Matthias Neumann)

• Dual Memory (Brian Stawn, Karla Sierralta)

• Passages of Light: The Memorial Cloud (bbc art + architecture)

• Reflecting Absence: A Memorial at the World Trade Center Site (Michael Arad)

We're Being Shut Out Of The Process

The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and its approach to families, is a major issue. Think about how fast this is moving forward. Why is this being pushed? Did they steal into Pearl Harbor and have an amusement park there right away? It doesn't seem right to me that it's happening so quickly

The reason the memorial process is moving so quickly is because they're not getting input from everybody. They're getting input from a few select people who are going along with what those in charge want, playing their game. They don't want to hear from families that are unhappy.

They don't want to hear that families don't want a PATH train pulling into the World Trade Center, on top of maybe tiny remains. They don't want to hear that fire families want their brothers listed together, and police families want their brother and sisters listed together. They want to hear what they want to hear, and that's why they shut out the families that don't agree with what they want.

Plain and simply, I want that my brother Sean Tallon be listed with his fellow firemen, that the policemen be listed together, and that each group -- the EMTs, the court officers, the civilians - be given recognition. I really would like to see my brother listed with the firemen he was with that day, because that's the only consolation I got, that Sean was with his fellow firefighters, and I knew he didn't feel alone as he was scared climbing up those stairs. I don't think it's too much to ask, considering all that they gave and all my family gave that day.

If this doesn't happen, I will remove Sean's name from that memorial, or at least fight to have it removed. I would rather stand down at Ground Zero with a piece of oak tag every September 11, with my brother's name and what he did, and tell my little girl in the future 'we didn't let his name up there, because the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation didn't do the right thing.

Rosalen Tallon's brother was a firefighter who died on 9/11. This essay was adapted from an interview.

######

Also In This Series

• The Eight 9/11 Memorial Designs

• Rethink The Type Of Memorial We Want - by Max Page

• Let The Memorial Jury Do Its Work - by Charles G. Wolf

• We're Being Shut Out Of The Process - by Rosalen Tallon

The Eight Memorial Finalists

• Votives in Suspension (Norman Lee and Michael Lewis)

• Inversion of Light (Toshio Sasaki)

• Garden of Lights (Pierre David, Sean Corriel, Jessica Kmetovic)

• Suspending Memory (Joseph Karadin, Hsin-Yi Wu)

• Lower Waters (Bradley Campbell, Matthias Neumann)

• Dual Memory (Brian Stawn, Karla Sierralta)

• Passages of Light: The Memorial Cloud (bbc art + architecture)

• Reflecting Absence: A Memorial at the World Trade Center Site (Michael Arad)

From Cop To Councilmember

One morning in 1983, I was in front of my house sitting in my mother's car. Suddenly, I was approached by two white police officers who accused me of stealing the car. The officers dragged me from the car at gunpoint, slammed my head and body repeatedly against the car and pointed their guns inches away from my head. I was handcuffed and taken to the police station. No charges were ever filed, but that day, I suffered not only bruises, but also the humiliation of false arrest.

Since that day, I have tried to turn that experience into something positive. I became a correction officer and worked at Rikers Island for two years. A few years later I became a New York City police officer and an instructor at the police academy where I trained officers on proper arrest procedures and how to interact with people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. In 1991, I started a not-for-profit organization called 'LOVE YOURSELF" Stop the Violence to address the growing urban violence. As a part of my campaign, I stopped Toys R Us from selling lookalike toy guns, I denounced violent music lyrics on the radio and images on television during the hours when children are watching and I aggressively protested incidents of police brutality. Now as a City Council member, I bring all my experiences together to help reduce crime and improve policing in the 35th Councilmanic District in Brooklyn and around the city.

I believe a successful police department is one that not only addresses crime, but is also responsive to the concerns of the community. The first step in accomplishing this is making the local precinct a welcoming place. As an African-American I do not always feel welcome when walking into a police precinct. This is true even though I am a former police officer. I compare this feeling to being in a restaurant and receiving poor service. It does not matter how good the food is, if the waiter does not greet you properly and has a bad attitude, you don't want to eat there. On the other hand, if you are greeted with courtesy and respect, it goes a long way towards your feelings about the restaurant. A police precinct is no different. Local residents should be able to go into a precinct and have their needs addressed in a courteous and professional manner. In the academy, police officers are trained that when dealing with crime victims, they should strive to leave them feeling better than when they found them. I take that goal very seriously.

In my City Council district in Brooklyn, there are four precincts: the 71st, 77th, 84th and 88th. That means my district has four different commanding officers with four different styles of policing. Some precincts are more focused on issuing tickets, some are more community friendly, and others are more aggressive in their tactics. My job as the City Council member is to communicate with all these commanders. I also have to help the community learn to embrace good police officers. To just speak out against bad cops is unfair. The community has to acknowledge the good cops also, so that when speaking out against bad cops, there is more credibility to it and the complaint is taken more seriously.

After September 11th, the police department added concerns about terrorism to their local policing responsibilities. I sit on the City Council's public safety committee and recently we met with Police Commissioner Ray Kelly and Deputy Commissioner of Intelligence David Cohen. One of the things I asked about was NYPD's cooperation with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Before September 11th, the FBI and NYPD worked more independently. Now we need to make sure that there is more of a joint effort so that local police have all the necessary resources to provide maximum security for our communities at large.

As the chairman of the committee on juvenile justice, I am also committed to improving the way New York City handles youth crime. Currently, the juvenile detention centers act as their own school system with a track from one detention center to the next. Too many youths graduate from juvenile detention centers, go on to jail, then go to prison upstate. We have to stop that cycle. Something is wrong when a detention center fails to rehabilitate but instead leads a youth into a permanent life of crime.

Mayor Bloomberg has put $64.5 million in the budget to expand detention centers. I feel the money should not go into detention, but into prevention. We need to reduce the ratio of youths per caseworker, so we can get kids the help they need. We need to continually reassess our youth crime prevention and detention strategies. Education is the best form of crime prevention. If a person is educated, he or she will be less likely to commit a crime. Class sizes have to be reduced and disruptive kids in our schools need to be properly addressed.

The 35th City Council district in Brooklyn is a diverse community. There are African-Americans, Caribbean-Americans, white Americans and Hassidic Jews all living together in the same neighborhood. When you walk down the street you see lawyers and doctors as well as sanitation employees and firefighters. We have great educational institutions like Pratt Institute, St. Joseph's College and Long Island University. We have a vibrant arts community and powerful churches and religious institutions. I represent all of these people. One of the biggest challenges I face is getting all the elected officials -- the community boards, the other City Council members, the Bor ough President, the State Senators and Assembly members -- who represent the area to be on the same page. It is our job to make sure that the whole community prospers.

Sometimes, like police officers, politicians forget that the people pay our salaries with their taxes. We have to remember that we are here to serve the people.

Posted March 25, 2002.

New York City Council STATED MEETING - November 19, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - November 19, 2003

Quote of the Day:

"We all witnessed the loss of a warrior, the late Councilman James Davis, whose shoes I cannot fill, but whose legacy, vision and spirit I will keep alive." - Councilmember Letitia James, being sworn in after winning the vacant seat of slain Councilmember James E. Davis.

Meeting Summary:

With much fanfare, Letitia James was officially sworn in as the new City Council member for the 35th district in Brooklyn. She fills the vacant seat of slain Councilmember James E. Davis, who was shot in City Hall on July 23, 2003.

James, who ran on the Working Families Party line in the November election, won by a wide margin and defeated three other candidates, including Democrat Geoffrey Davis, the brother of the deceased council member.

"We recognize that this victory was born out of tragedy," said James. "It is difficult for me to celebrate. But it is essential that we bring about unity. Unity is the greatest need this hour."(Read her full speech)

James's entrance into the City Council chambers was carefully choreographed for photographers, and Speaker Gifford Miller escorted James onto the council floor where she took her oath of office. A crowd of supporters and family members attended the meeting and they cheered when James cast her first "yea" vote on a series of landuse items.

While new to the council, James has a long resume of political experience. She served as an aide to Assemblyman Roger Green, worked in the office of the state attorney general, and established the Urban Network, a coalition of African-American professional organizations that promote education. James narrowly lost the 2001 election to James Davis.

James promised to work on issues like affordable housing, health care, and education and to create employment opportunities in the district. (Read about development issues in the district.)

After the ceremony, the council had a light legislative agenda.

The members unanimously voted for a measure that adjusts the property tax rates for one, two, and three-family homes. The measure was a required response to a state law passed in August. While the action actually shifts some of overall property tax burden from homeowners to utilities and commercial real estate owners, most homeowners will still see an increase because their property values have risen considerably in the last year. The average homeowner will see a $48 increase in their November property tax bill.

"None of us will be able to explain that to our constituents because I can barely explain it myself," said Brooklyn Councilmember Lewis Fidler, who called for a reform of the property tax laws.

The council also approved a business improvement district (Intro 564) on Sutphin Boulevard in the Jamaica Center area of Queens.

The most hotly debated measure of the day concerned a resolution (Res 1133) denouncing former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad for his anti-Semitic remarks. At a recent conference, Mohamad said that "Jews rule this world by proxy; they get others to fight and die for them."

Brooklyn Councilmember Charles Barron voted against the resolution because he said he was tired of the City Council's "pro-Israel agenda." Speaker Miller defended the measure. "This has to do with bigoted, hateful, and offensive remarks," said Miller.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for December 3.

For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.

The Office of the Future Today

Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently took on a problem that annoys a growing number of New Yorkers. Many new cell phones take photographs, offer games and play music, but do not make calls -- at least not in numerous places throughout the city. "Cell phone 'dead spots' are frustrating and too common," the mayor announced. The city's solution: When New Yorkers find these dead spot zones, they should dial 311 to report them. And then what? "This program will undoubtedly help the industry improve service and help consumers make more informed purchasing decisions," the mayor said.

Other articles in this series:

|

And this in a nutshell is the dilemma facing the city. If New York has its most tech-savvy mayor ever -- an entrepreneur who made billions providing technology to businesses and whose pet projects at City Hall include tech innovations such as the 311 telephone number for non-emergencies -- one public official can only do so much. The city has so far been better at identifying local tech problems than in solving them.

Will the typical New York City workplace of the 21st century be like Terry Gilliam's 1985 film "Brazil" (shown above), where a house fly can plunge the whole makeshift technology and telecommunications system into chaos?

Will the typical New York City workplace of the 21st century be like Terry Gilliam's 1985 film "Brazil" (shown above), where a house fly can plunge the whole makeshift technology and telecommunications system into chaos?But these problems, some say, are more than just an inconvenience; solving them is essential if New York City is to remain a capital of communications and commerce. Will the typical New York City workplace of the 21st century be like the graceful high-tech offices of Steven Spielberg's movie "Minority Report," where Tom Cruise waves his hands in the air and is instantly connected to an information superhighway? Or will it be more like Terry Gilliam's 1985 film "Brazil," where a house fly can plunge the whole makeshift technology and telecommunications system into chaos?

WHAT TODAY'S OFFICES NEED

The August 14, 2003, blackout dramatized many of the flaws in New York's communications systems. The Internet was useless. Cell phone providers could not handle the increased demand for calls and, as the blackout continued, service deteriorated further. Many office phone systems, dependent upon electricity, also failed to function.

But it does not take an extraordinary event like a blackout to point out the problems that businesses face. According to a report by the Center for an Urban Future, New York has become "one of the worst environments for entrepreneurs and growing firms," ranking at the bottom of national lists. One reason for this is its poor telecommunications technology. Meanwhile, advances in technology that enable people to "telecommute" and easily work with people hundreds of miles away make it less essential for many businesses to stay in New York. Experts agree that faced with such challenges, New York will lose businesses, jobs and money if things don't change.

Of course, the office of the future does exist right now in New York. Employees in many offices communicate almost entirely by computer, e-mailing colleagues, customers and contractors around the world, and checking stock prices, political trends and industry data on the Internet. Large businesses host their own Web sites, set up wireless networks in their offices, use voice-over-Internet technologies to cut phone costs and hold online conferences. Orders come in over the Internet, and customers track the status of shipments by computer.

An increasing number of people spend much of their business day away from a traditional office, working on portable devices such as laptops, personal digital assistants and cell phones. A salesperson may visit a client and then e-mail a report on the meeting while sitting in a nearby cafe or park. An electrician at a building site needs to check on the availability of a part; the site has no phone service yet, making him completely dependent on his cell phone. Every day, people need to connect to files, programs, databases and the Internet from their apartments, their local park or even Yankee Stadium.

Such new technologies increase efficiency and cut costs. But many businesses outside midtown and lower Manhattan cannot take advantage of them, because of aging or outmoded wires and cables, or because they simply are not available anywhere but the two major business districts.

HIGH SPEED INTERNET ACCESS

An image from Steven Spielberg's movie "Minority Report," where Tom Cruise waves his hands in the air and is instantly connected to an information superhighway.

An image from Steven Spielberg's movie "Minority Report," where Tom Cruise waves his hands in the air and is instantly connected to an information superhighway.Just about anyone with a telephone and a computer can get access to the Internet. But, as anyone who uses a dial-up system at home knows, access can be painfully slow and tie up telephone lines.

That is why many businesses are looking to "broadband," which is a high-speed connection to the Internet such as a digital subscriber line or DSL (which uses the phone lines), or cable-modem (which sometimes shares the wire used for cable television). Unlike dial-up, broadband is always on, so there is no connecting and disconnecting.

Any business that makes or takes orders for merchandise can benefit from broadband. Conducting such transactions by dial-up Internet or telephone can be slow and frustrating as screens can freeze and information can be lost.

"Broadband is critical for economic development and small business growth across the board, not just in high-tech industries," says Jonathan Bowles, research director at the Center for an Urban Future, who has been interviewing small businesses on the importance of broadband for a report to be released next month.

The problem is that broadband is not widely available in the city outside of midtown and lower Manhattan.

For example, cable DSL and cable modem are extremely difficult to get in Brooklyn, largely because providers consider it a low income area, City Councilmember Gale Brewer, chair of the council's technology committee, told Wireless Review this summer. "A year ago, a senior citizen center with a multimillion-dollar budget wanted to put in broadband, but no one wanted to go there," Brewer said. "I've worked in a lot of low-income areas in New York City, and private companies always think there's no marketplace there. We have to get this to go beyond the central business district."

Experts claim that if broadband were made available in just 50 percent of the city, it could bring in an extra $15 billion to the New York economy over the next 25 years. Providing service to 94 percent of New Yorkers could bring in $80 billion.

The lack of broadband places a heavy burden on many nonprofit groups, says Kayza Kleinman, director of the Nonprofit Helpdesk at the Jewish Community Council of Greater Coney Island. Government regulations require that many social service agencies provide services and information online, something difficult to do without high speed Internet access. As a result, many struggling organizations have felt forced to wire their buildings themselves, at a cost they cannot afford. And those are the ones lucky enough to be in an area where such wiring is possible.

Simply providing high speed Internet access is only the beginning. Even when service is available, some small businesses and nonprofits cannot afford it. While prices for most telecommunication services have been falling, broadband prices have gone up. Many organizations pay at least $400 per month so that a number of computers can be online at the same time.

The relatively high price is due largely to a lack of competition. While there are 18 broadband providers other than Verizon, most of them must lease the wires from Verizon and thus have to pay Verizon for access.

And there are different types of broadband. While all may be high speed, exactly how fast one can send and receive information may vary. Such differences present particular problems for companies that want to host Web sites and e-commerce platforms. "All broadband is not equal," says Joe Plotkin of Bway, a New York-based Internet-service provider that provides symmetrical broadband.

FIBER OPTICS

There are two ways for telephone companies, such as Verizon, to make high-speed Internet more readily available. They can replace the copper wires that currently run under much of New York City, with newer ones that are better able to handle massive amounts of information. Or they can upgrade to fiber optics. These cables -- strands of glass about the size of a human hair that transmit light signals -- allow Internet connections that are four times faster than broadband and could be ten times faster in the future.

But 87 percent of the city's fiber optic cables are in Manhattan business districts below 59th Street. One obstacle to expanding their reach is money. Fiber optics cost as much as $40,000 per mile to install, while wireless costs a tenth as much, according to one study.

HOTSPOTS

It is a truism of work in the 21st century that many people must be accessible around the clock -- in the office or away -- and so rely on being able to use cell phones and laptop computers wherever they might be.

Key to this are "hotspots" that provide a wireless Internet connection people can use with their laptops, personal digital assistants and other devices over the airwaves. Wireless, which is comparatively cheap to set up, can bridge gaps between other services. Currently, there are hundreds of free hot spots in business and residential areas of Manhattan as well as in the outer boroughs. (See map.)

The non-profit group NYCwireless has joined with economic development groups and parks organizations to provide free Internet access in places such as Bryant Park and lower Manhattan. Verizon offers wireless to their paid broadband customers at telephone booths, and T-mobile connects Starbucks customers for a monthly fee.

The city hopes to create schools, libraries and other government buildings as wireless hotspots. But wireless is still on the cutting edge. Many people do not know that wireless sites are available, and most small businesses have not yet begun to explore how wireless can help them. And even though wireless is spreading here, it is still not as popular in New York as it is in places such as Portland, Oregon, and Orange County, California.

PLANNING FOR THE HIGH-TECH FUTURE

While there is widespread agreement on at least some of the technology the city will need for its economy to thrive in the coming decades, less agreement exists on how to achieve it. Much of the controversy involves who should pay for the improvements.

Many believe that upgrading the city's wires and cables is the job of private companies such as Verizon, Con Edison, Time Warner Cable and Cablevision that profit from providing such services. As it stands now, the companies do shoulder most of the cost and make only those improvements they feel are worthwhile for them. For example, to justify the cost of installing new cable, Verizon must believe that it will gain a significant increase in business once the cables are installed.

Others say the need for fiber optics and other improvements is so crucial to the general well being of the city that it cannot be left to the private sector alone.

In May 2003, the City Council published a report, "Network NYC" (in pdf format) which laid out a proposed long-range telecom strategy. Many of the report's recommendations involve increased planning and analysis of the city's telecommunications needs by the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications.

But the report also called on the city to use its economic clout as a major purchaser of telecommunications services to get improvements in service. New York City spends over $130 million annually on telecommunications, primarily telephone and Internet, more than any other city in the country. At least 75 percent of that goes to Verizon - with no competitive bidding. The report and the city comptroller have questioned whether the city should solicit competing bids to cut costs and perhaps exert influence on Verizon. (The company could not be reached for comment.)

The report also urges the city to make better use of existing technology. For example, it notes, the city manages franchises with a number of fiber optics companies and controls rooftops through New York that could be used for wireless. Yet, despite this, it says, "there has been little public discussion or long term strategic thinking about how the city could better organize this public and private infrastructure to encourage a truly citywide deployment of affordable, high speed networking capacity."

Because laying new fiber optic cable is so expensive, Councilmember Brewer recommends using existing fiber optics - either lines already owned by the city or leased from other owners - and combining them with wireless to create a network linking every borough but Staten Island. Brewer sees such a network helping small companies and non profits that cannot afford $400 to $1,200 a month to get high-speed Internet access from Verizon.

Another possibility involves taking old systems and putting them to new uses. The city explored the possibility of putting telecommunications equipment, including fiber optics, in space occupied by unused water pipes.

Some fiber optic cables -- called dark fiber -- were installed in the ground during the high tech boom of the 1990s. But they were then abandoned as dot.coms went bankrupt. Providing new cable to link to this unused dark fiber could be a lower-cost way of bringing fiber optics to at least some parts of the city.

As appealing as some of these ideas are, any solution is bound to be for the short-term only. In the 21st century, technology often becomes outmoded before many of us ever get to use it. And so fiber optics, broadband and hot spots could all soon be eclipsed by better, cheaper technology that has not been developed yet.

But whatever the actual technology, New York will have to stay on top of it. And that requires a vision, a plan and a way to put it into action.

Steam

When John Velez, co-owner of Sutton Cleaners, arrives at work at 7 a.m. on Manhattan's East Side, he opens a steam valve in the back of his shop. "When I come into the shop in the morning, it's one, two, three," he says, "and you're up and running in less than a minute."

Other articles in this series:

|

Nearly every piece of equipment that Velez will operate for the rest of the day uses steam. The spotter shoots out steam to remove stains while a puffer sends out steam to remove wrinkles. The dry cleaning machine and the pressing machine also use steam.

So do Rockefeller Center, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the United Nations -- which use it for heating and cooling - along with some 2,000 other customers and 100,000 buildings, from residential low-rises to commercial skyscrapers. All are in Manhattan, primarily because steam is most efficient and cost effective for high-rise buildings.

The City of New York is one of the largest consumers of steam. The Roman Catholic Church of St. Peter in lower Manhattan began using steam to warm its sanctuary in 1882, the year the first steam generation plant went into operation in New York. The church has used steam ever since.

NOT JUST A GIANT STEAM KETTLE

Some 30 billion pounds of steam every year flow beneath the streets of Manhattan from the Battery to 96th Street. While it is unknown to most New Yorkers, Con Edison's subterranean steam system is the biggest steam district in the world, larger than the next four largest U.S. steam systems combined and boasting an annual steam production more than double that of Paris, Europe's largest system.

If steam is an easier concept to grasp than, say, fiber optics, producing it on this scale is nowhere as simple as turning on a giant teakettle. Some of the steam comes from the Con Edison steam generating plant on 14th Street and the East River. Inside, two massive boilers -- one 95 feet high -- burn natural gas or fuel oil and air. The resulting heat sends the temperature of water inside the boiler's pipes to a blistering 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit, converting it to steam. Workers wear ear protectors to keep out some of the roar of millions of gallons of flowing water and the sound of spinning turbine blades. Little, though, can shield them from the warmth radiating from pipes filled with superheated vapor.

"When we used to bring people into the plant for tours, their first impression, when we have them look inside of the furnace, is that it's huge. People are taken back by the sheer size of it - eight stories high," says Wilton Cedeno, former manager of Con Edison's Hudson Avenue steam plant. "There are intricate control systems -- systems for treating the water, electrical systems, pressure systems. It's all very complex."

On average, the plant converts a gallon of water into eight pounds of steam -- every hour, approximately 125,000 gallons of water are turned into more than one million pounds of steam. "We use city water, but the water has to be processed and cleaned," says Cedeno. "If it's not pure, you get build up on pipes and can damage the turbine blades."

The East River plant is one of seven Con Edison plants -- five in Manhattan and one each in Queens and Brooklyn. Three of these plants, including the one on the East Side, produce both steam and electricity through a process called co-generation. In these plants, the steam leaves the boiler and then goes through pipes into a turbine generator. The resulting spinning of the turbine blades produces electricity. The remaining steam then goes into the steam system.

From the plants, the steam goes into Con Edison's underground pipes. On a cold winter day, nearly 10 million pounds of steam at 350 degrees Fahrenheit flow each hour through 105 miles of underground mains. The pipes coming out of the plant can be several feet in diameter, but the steam travels through progressively smaller pipes, ending at ones that may be only a couple of inches wide.

STERILIZING, HEATING, CLEANING -- NOT SEEPING FROM MANHOLE COVERS

The steam coursing under Manhattan is not to be confused with what is popularly called steam rising from many city manholes. The steam in the pipes is invisible, while the so-called steam wafting up from the streets is often vapor produced when underground water hits hot equipment and escapes from beneath the streets. It can also be condensed steam leaking from the Con Ed system.

Some of the real steam winds up at St. Vincent's Hospital on 12th Street, where the forceps in the operating room are sterilized using steam. Every day nearly 200 cleaning trays of surgical instruments pass through the Central Sterilization unit at St. Vincent's. A cleaning tray can contain anywhere from six to 130 pieces of surgical steel, depending on the size of the instruments. First, the trays are placed in a washer-disinfector, similar to a regular dishwasher. Then the trays go into the sterilizer where steam circulates inside. The intensity of the heat from the steam kills any viral or bacterial pathogens.

Most of the steam, though, is used for heating and cooling. Steam used for heating flows from Con Edison's underground mains into a building's internal heating pipes and then into a radiator where it heats a room. For cooling, steam flows from the main into a building's steam air conditioning unit.

The use of steam eliminates the need for boilers in individual buildings. Because steam from Con Edison's centralized plants is mass-produced, it is generally more economical, efficient and environmentally friendly than individual oil or gas boilers.

Joe Petta of Con Edison compares it to mass transit. "Which is better for the environment, 50 people riding to the city on a bus or 50 people riding 50 different vehicles? The emissions from one bus will be less than the emissions for 50 cars," says Petta. And he adds, the plants that produce steam are subject to "more stringent environmental and emissions controls than individual buildings generating their own heat either by burning gas or oil."

A NEGLECTED POWER SOURCE

Last year, Clean Air Communities -- a project of Con Edison, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the Northeast States Clean Air Foundations -- installed a new steam energy station in an underground vault at the Seward Park Housing cooperative, four apartment buildings with 1,728 apartments in lower Manhattan. The station, which ties into Con Edison's steam system, replaced four onsite oil boilers that burned approximately one million gallons of heavy fuel oil a year. This has eliminated traffic from fuel trucks and markedly cut air pollutants and reduced carbon dioxide emissions.

But many New Yorkers cannot follow Seward Park's example. Converting to steam often requires taking out an old boiler and putting in new piping and other equipment to link up with the steam distribution system. This can prove difficult and costly.

Partly as a result, Petta says, the number of steam customers has not increased in the past few years. "A lot of people don't know about it or don't know it's an option," he says. "Or building owners don't want to go through the conversion process and don't want to spend the money to convert."

And so, for now at least, steam remains New York's neglected power source. "The steam system is a great asset to the city and delivers clean energy," says Ashok Gupta, director of air and energy programs at the National Resources Defense Council, an environmental group. "We can clearly be doing more with it."