A Brief History of Election Law in New York

|

1665 - First Mayor

Governor Richard Nicolls appoints Thomas Willett the first "mayor of New York." For the next 156 years, the mayor will be appointed and have limited power.

1686 - Common Council

Governor Thomas Dongan divides New York City into six wards and creates a Common Council with an alderman and assistant alderman elected from each ward.

1820s - Property Qualifications Removed

In New York State, the right to vote is extended to all white males, regardless of whether they own or rent property.

1821 - Choosing a Mayor

The Common Council, which includes elected members, gains the authority to choose the mayor who will sit in City Hall. Previously, the state government appointed the mayor.

1834 - First Elected Mayor

An amendment to the state constitution provides for the direct popular election of the mayor. Cornelius W. Lawrence, a Democrat, is elected.

1846 - Voting Rights Rejected

New York voters reject a proposed amendment to the state constitution that would guarantee free blacks the same voting rights as whites.

1861 - Tammany Hall Emerges

Tammany Hall, which evolved from an organization of craftsmen into a Democratic political machine, gains control of Democratic Party nominations in the state and city.

1870 - Voting Rights

The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is ratified, giving blacks throughout the United States the same voting rights as whites.

1880 - Standard Ballot

In response to an era of political scandals, New York begins requiring the so-called "Australian ballot," a uniform ballot listing all candidates. To get on it, an office seeker would have to be nominated by a political party or submit nominating petitions, laying the groundwork for a system that persists to this day.

1890 - Primary Election

Because of perceived abuses in the way political parties select candidates, the New York State Legislature enacts a law that, for the first time, requires government to manage and pay for elections to select party officials who would then choose the party's candidates.

1892 - Voting Machine

The first voting machine, invented by Thomas Edison, is used in Lockport, New York in 1892. By the early 1920s, voting machines would be used for all general elections in New York City.

1894 - Bipartisan Control

The state establishes a system, in effect to this day, under which all election positions, from Board of Elections officials to poll watchers, must be divided equally between the two major parties.

|

1898 - Greater New York Formed

A new City Charter merges Manhattan, the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island into greater New York. All five boroughs now elect the mayor.

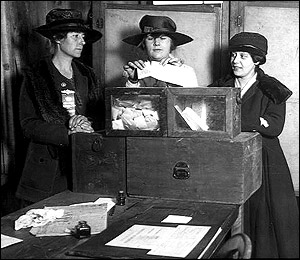

1915 - Suffragists Defeated

A referendum giving women the vote is defeated by city and state voters.

1920 - Suffragists Victorious

The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is signed into law, guaranteeing women throughout the United States the right to vote.

1965 - Opening the Polls

Congress passes the federal Voting Rights Act to ensure that no person is denied the right to vote on account of race or color.

1967 - A Black District

A suit brought under the Voting Rights Act leads to the creation of a majority black congressional district in Brooklyn. Previously, black voters had been divided among several predominantly white districts. In 1968, voters in the district elect Shirley Chisholm as the first black woman ever in the U.S. House of Representatives. Since then, congressional, state legislative and City Council districts have been drawn so as to ensure minority representation.

1969 - School Elections

Non-citizens who have children in public schools are given the right to vote in elections for members of community school boards.

1970 - Voting Rights in New York

The federal government determines that Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx must be covered under the federal Voting Rights Act because of low voter registration levels. As a result, the federal government has to approve any changes in voting practices in these boroughs, including redistricting. This would mean that any switch to nonpartisan elections would require clearance by the U.S. Justice Department.

1971 - Younger Voters

The 26th Amendment lowers the voting age in New York from 21 to 18.

1975 - Multilingual Ballots and Election Information

Amendments to the Voting Rights Act require that election information be provided in Spanish as well as English in Brooklyn, the Bronx and Manhattan.

1988 - Ethical Finance

The Campaign Finance Board is formed as part of a response to corruption in city agencies. Its goal is to limit the influence of private funds in city politics. Candidates participating in the program can receive public money for their election campaigns. In return, they must agree to a spending limit and full disclosure of their campaign finances.

1989 - End of Board of Estimate

The U.S. Supreme Court abolishes the Board of Estimate, which gave each borough president an equal vote. The court rules that this violates the principle of one person-one vote because the boroughs vary so much in population. A new charter eliminates the board and distributes the board's powers between the mayor and an expanded City Council. 1992 - Chinese Ballots

The city begins providing voting information in Chinese, and Spanish is added to Queens ballots.

1993 - Term Limits

City voters approve a ballot measure, backed by millionaire Ronald Lauder, that would limit citywide officials, including the mayor, as well as borough presidents and members of the City Council to two consecutive four-year terms.

1996 - Public Debate

A law is passed requiring candidates who run for citywide office and participate in the Campaign Finance Program to participate in a series of public debates in order to receive public matching funds.

Photograph by Steven McCurry |

1996 - Two Terms and You're Out

Voters reject a plan put forth by City Council Speaker Peter Vallone to delay the implementation of term limits and to allow officials three terms, instead of two.

2001 - Primary Date

The primary vote is originally scheduled for September 11. Voting begins that day but is halted after the attacks on the World Trade Center and postponed until September 25. With Primary Day always falling on the second Tuesday in September, some have urged the state to shift the election to keep it from ever falling on September 11. So far, such efforts have failed.

2001 - The Big Change

Because of term limits, all citywide officials and 37 of 51 City Council members are unable to run for reelection, creating the largest turnover in city history.

2003 - School Change

The state approves a law eliminating community school boards, replacing them with councils selected by parents.

2003 - Two More Years

The City Council adjusts the term limits law to allow some council members, who were elected in the middle of a term and would have had to leave office after serving fewer than eight years, to remain in their seats. The action cleared the way for Council Speaker Gifford Miller and four other members, who would have had to leave office in January, 2004, to seek re-election this November.

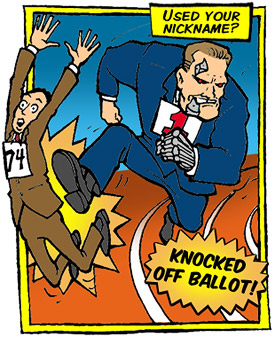

Ballot-Bumping in New York

|

"In New York, politics is a blood sport."

|

This summer, Democratic City Councilmember Allan Jennings earned the distinction of being one of the few incumbent politicians in New York City ever to be kicked off the ballot by his own party.

The Queens Democratic Party, which has a history of conflict with the one-term council member and is supporting another candidate, challenged Jennings in court, claiming that the 3,300 signatures on his petitions were riddled with fake and fraudulent information.

Jennings acknowledged some minor mistakes, such as missing addresses or signatures from people who had recently moved, but denied any wrongdoing. In mid-August, State Supreme Court Justice Janice Taylor - who has received the backing of the Queens Democratic Party throughout her career - kicked Jennings off the ballot.

Jennings appealed and spent the next nine days in court. His campaign workers and volunteers were called on to testify about how, when and where they collected signatures. "All of my petition people were senior citizens and they don't remember things precisely," said Jennings.

A five-member panel of the Appellate Division eventually reversed the lower court ruling, citing "irregularities" in the petitions, but no fraud. The council member was put back on the ballot.

"I feel personally vindicated," he said later.

But Councilmember Jennings may not be the best standard-bearer for the principles of democracy. The council member himself sued all of his opponents in an effort to kick them off the ballot for the same kind of technicalities; he succeeded in narrowing the field of challengers from five to two.

"Using these type of shenanigans to deny the voters the right to choose is shameful," said Inderjit Singh, one of the two opponents who successfully defended their signatures.

In New York, which has some of the most complicated election laws in the nation, knocking your opponent off the ballot is a routine aspect of the political game. This year, dozens of candidates for City Council were eliminated on technicalities. And many more potential challengers did not even bother running, knowing that they would face huge legal bills and hours in court defending their right to run. (For a dozen council races worth watching this year, see Campaign 2003)

The process not only limits voters' choices, but it means the candidates spend more time in court than they do meeting the voters and hearing their concerns.

"In New York, politics is a blood sport," said election lawyer Henry Berger.

|

|

Candidates have been knocked off the ballot for such infractions as writing the abbreviation "St." instead of "Street"

|

Battle To Get On

This summer, California has become the butt of political jokes with its recall election and a long list of candidates for governor including actor Arnold Schwarzenegger, activist Arianna Huffington, baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth, child actor Gary Coleman - and a porn star, a boxer, and a sumo wrestler.

But if the race were suddenly to be governed by the election laws and practices of New York, it would become absurd in exactly the opposite way -- none of the candidates would even make it to the ballot.

In California, one need only gather 65 signatures and pay $3,500 to get on the ballot for governor. In New York City, a candidate for the far more lowly post of City Council has just a few weeks in the summer to collect at least 900 signatures from voters in their district who are also registered in their political party. And the candidates have to make sure that the petitions, the pieces of paper where the signatures are collected, adhere to every little rule. No fourth-grade penmanship teacher was ever as strict.

Most experienced candidates, knowing that they will end up in court defending their petitions, collect 2,000 to 3,000 signatures.

For Republican or smaller party candidates trying to run in areas dominated by Democrats, it can be a daunting task. Sal Grupico, a Republican running in district 45 in Flatbush, Brooklyn, had trouble finding enough Republicans to sign his petitions. "I think most of them are gone and dead," he said.

The concept of gathering signatures on petitions dates back to the late 19th century. It was supposed to help eliminate the political parties' control of the ballot, according to Douglas Kellner, a commissioner at the Board of Elections. (See timeline of New York election law)

Before that, there were no printed ballots in New York. Voters simply went to the polls and wrote down the candidates of their choice. To instruct voters on who was running, political parties printed up a slate of candidates, which the voters could take with them to the polls.

This system had many problems, one of which was that political parties often printed counterfeit lists of candidates to deceive supporters of the opposition. "A counterfeit ticket would list a few of the party's prominent candidates - just enough to fool the unwary - with the rest of the names coming from a rival slate," said Kellner.

To clear up the process, the government began in 1880 to print a uniform ballot that would be presented to voters to fill out at the polls on Election Day. Political parties were allowed to nominate their candidates to be listed on the ballot. But in addition, candidates not selected by the party could get on the ballot anyway if they could submit enough signatures from voters.

To ensure that the signatures were valid, a series of rules were put in place - many of which are still used today.

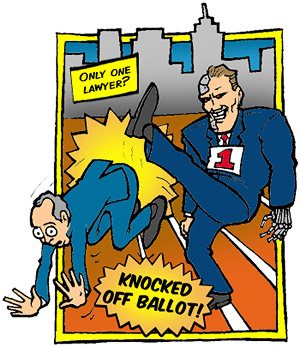

Ironically, these rules set up over a century ago to assure a more open, honest and democratic process of elections have become just the opposite -- a powerful tool for political parties and incumbents to maintain their advantage. To these New York politicos, the best elections are those in which there is only one candidate left on the ballot for voters to choose.

|

|

"It is not clear that any of these rules prevent fraud...It is incredibly trivial stuff that often trips up candidates."

|

Devil in the Details

Many incumbents, backed by their political party, have teams of lawyers who will go over a challenger's signatures, line by line, looking for minor mistakes like missing zip codes, misspellings, and voters who have signed petitions not knowing whether they live in the district or not.

In the past, candidates have been knocked off the ballot for such infractions as writing the abbreviation "St." instead of "Street" or forgetting to staple a cover sheet.

If the person gathering the signatures - called a petitioner - makes a mistake such as forgetting to write the borough on the bottom of the page, all of the signatures that he collected can be thrown out. If enough signatures are declared invalid, a candidate is eliminated.

This year, in the district 48 race in Coney Island and Gravesend Brooklyn one candidate was kicked off of the ballot because he petitioned under his common name Tony Eisenberg, rather than under his legal name Anatoly Eyzenberg. The Russian immigrant who has been in the United States for 23 years said that when he came to New York, he "Americanized" his name. "My wife, everyone calls me Tony - I forgot my name was Anatoly," he joked.

The argument for such complex and obscure rules is to protect against fraud and allow only serious candidates on the ballot.

Every so often, the press gleefully reports some obvious example of fraud; a court challenge to the petitions of Manhattan City Councilmember Alan Gerson revealed that they included the signature of a dead woman. Elsie Roloan, who died on June 22, nevertheless signed Gerson's petition four days later.

Gerson, who serves lower Manhattan's district 1, denied any wrongdoing and told the New York Post that it is nearly impossible for a candidate to know what is happening during the signature gathering. "I have no control or oversight over the petitions in question," Gerson said. "This suit is a total waste of the judiciary's time. It's frivolous."

Even those who believe that dead people should not be involved in the political process have to agree that such litigation, and the rules that encourage it, do not accomplish their supposed big-picture aim: Surely, nobody really doubts that an incumbent like Gerson is a serious candidate. Experts say that the rules, while useful as weapons by political opponents, in fact do little to protect voters.

"It is not clear that any of these rules prevent fraud," said Columbia Law Professor Richard Briffault. "It is incredibly trivial stuff that often trips up candidates."

The Board of Election officials and judges ruling on the cases often owe their seats to the same party organizations trying to get rid of all challengers, and so are slow to accept reforms.

In the case of Councilmember Allan Jennings, the judge who knocked him off the ballot, Justice Janice Taylor, was backed by the Queens Democratic Party, which a decade ago helped her reach the bench despite a rating of "not qualified" by the bar association, according to a recent article in the Daily News.

And even for candidates who admit the system is a mess, ballot challenges become a necessary part of the political process.

After being knocked off the ballot in 2001, Washington Heights council candidate Victor Bernace, a lawyer who usually defends cab drivers, learned the complexities of election law and this year challenged a less experienced candidate, Pedro Morillo. Bernace set up a headquarters at his kitchen table with five borrowed laptop computers and friends who worked round the clock to look for errors in his opponent's signatures.

"You get hit by the system, then you learn, then you do it to someone else," said Bernace. "It's really a silly game."

|

|

"My wife, everyone calls me Tony," says Anatoly Eyzenberg, who was kicked off the ballot for using the name he has had since immigrating 23 years ago.

|

National Embarrassment

New York's Byzantine election laws received national attention in 2000, when Arizona Senator John McCain, who was running against George W. Bush in the Republican Presidential Primary, was knocked off of the ballot by his own party.

At the time, New York's election law required that a candidate collect thousands of signatures from each of the 31 congressional districts across the state, including areas of the city with few Republicans. Governor George Pataki, who supported Bush, used the laws to keep McCain out of the running.

McCain, who had already won the New Hampshire Primary, denounced the state's "Stalinist politics."

A federal judge eventually put McCain back on the ballot, but not before dozens of editorials across the country mocked New York's political process. That same year, Republican Steve Forbes spent $750,000 just to get on the primary ballot.

After the national embarrassment, state lawmakers instituted reforms. But local races are still decided as much in the courtroom as in the voting booth. The battles make for some very bizarre tales.

Bumped By The Dead

Even after James Davis was shot and killed in City Hall in July, lawyers for the slain council member continued their challenge of Davis's opponent Anthony Herbert in district 35 in central Brooklyn.

The Board of Elections removed Herbert because dozens of the petition sheets failed to include the city and county of the person collecting the signatures. To avoid such problems, many candidates have the name of the city and county pre-printed on the petition sheet, but Herbert, who was running for the first time, overlooked the detail. Even though Herbert collected more than 2,000 signatures, he found himself with half the amount needed after the challenge.

"Anthony Herbert may go down in history as just another exhibit showing that you don't challenge insiders," said Herbert's lawyer Victor Bernace. "Even a dead man can kick you off the ballot in New York."

Herbert, reportedly enraged at being unjustly maneuvered off the ballot by his party, has announced that he will run for the seat in the general election on the Republican line.

Fighting the Family

Bronx Candidate Luana Rodriguez found herself fighting the most powerful political family in the Bronx when she tried to challenge 24-year-old Councilmember Joel Rivera in district 15.

Councilmember Rivera's father is Jose Rivera, State Assemblyman and chair of the Bronx Democratic Party. Joel's mother is the district manager of community board 6 and her son's former campaign manager. Joel's sister is the deputy chief at the Bronx Board of Elections.

The Rivera's used all their forces to work to knock her off the ballot, Rodriguez said. She was disqualified when two of her witnesses, those who collected and verified the petitions, were found to not be registered Democrats living in the district.

Rodriguez said she never stood a chance in challenging the ruling. "I counted 10 lawyers for the other side," she said.

|

|

"I counted 10 lawyers for the other side," said Luana Rodriguez, who was kicked off the ballot by the Rivera clan of the Bronx.

|

Borough Park Brawl

In Borough Park, Brooklyn a former council member, Noach Dear, who was barred from running this year by the term-limits law, tried to sue his way onto the ballot. He even circulated petitions, gathering signatures from voters who had no idea that he cannot legally run again until 2005.

Incumbent Councilmember Simcha Felder filed a counter lawsuit to block Dear from appearing on the ballot and threatened to garnish his salary if elected. "If he's circulating petitions, he's deceiving voters," said Felder.

After months of legal wrangling, Dear was barred from running. Those who see this as a triumph for democracy, or at least for the rule of law, may find it bracing to learn that, this fall, Councilmember Felder is running unopposed on the Democratic, Republican, and Conservative party lines.

Worse Than The Worst Country Club

Even Republicans, who have a slim chance of winning in a Democratic district, wage fierce battles with each other before primary day.

In district 32 Republican Richard Iritano said he was locked out of the process when the party refused to even talk to him. Iritano was then knocked off of the ballot after the Board of Elections ruled that 521 of his petition signatures were altered. Iritano said that the claim was "complete nonsense because all of the petitions were collected by myself and my mother."

Republican Michael Mossa challenged Iritano's petitions, and when Iritano tried to defend his case in court, he said that the judge reprimanded him for wasting the court's time. "The whole campaign was an exercise in futility," said Iritano. "I haven't seen this kind of exclusionary behavior even in the worst country clubs."

Chances for Reform?

|

Reforming New York's laws is a nearly impossible undertaking given that political parties and incumbents in power see the system as working just fine. And most election-reform groups in the state work on other issues like same-day registration and poll worker training, not trying to rewrite election procedures that have been in operation since 1880.

There have been some minor changes in recent years, trying to cut down on some of the obscure regulations. A series of federal lawsuits have overturned some state rulings and some judges have been shamed into being more lenient.

Experts concede that these have not been enough. "There is a sense across the country that New York has the worst laws in the country," said Briffault.

These laws are not just bad for candidates, but for voters.

"Often it appears that candidates spend more time in court trying to knock each other from the ballot than they do explaining themselves to potential voters," Governor Mario Cuomo wrote in the New York Law Journal. "The State has no interest in denying qualified candidates an ability to be on the ballot and to be judged on their own merit. Unfortunately, New York's ballot access law does just that."

*******

Campaign 2003 -- Election Coverage:

• A Dozen Council Races to Watch

• A Brief History of Election Law in New York

• Gotham Gazette Looks at City Council Campaign 2003

*******

Series of Campaign Tangle articles from 2001:

• Campaign Tangle Begins

• A City of Challenges

• The Rejected Candidates

• Chaos and Confusion

• The Battle for District Attorney

• Disillusioned Candidates

Primary Elections, And The Ballot Proposals For November

On September 9, 2003, New York City will hold primary elections for city council races, in order to nominate candidates for the general election to be held in November. According to New York City election law, once every twenty years city council members serve back-to-back two-year terms, instead of the normal four-year terms. It is a provision that allows the city to incorporate the latest census data into redistricting measures. In 2001, the city council members all stood for a two-year term, and so they are returning this year for another two-year term. Out of the 51 members of the city council, all of whom are up for reelection, there are primaries in 26 of those districts. For details, check out Gotham Gazette’s Campaign 2003 , which is part of the Community Gazettes.

Most of the primaries are on the Democratic side, with the Democratic incumbent challenged in his or her nomination for reelection. But there are two Republican primaries. This is in and of itself unusual enough in a city where Republicans represent roughly only 16 percent of all registered voters, but one of these contests is close to unheard-of. Two candidates, Jennifer Arangio and Douglas Winston are vying for the chance to unseat Democratic City Council Speaker Gifford Miller. That either Republican hopeful would make that kind of history is highly unlikely.

The primary election itself may soon be a part of history, depending on the outcome of the November elections. The Charter Revision Commission recently approved three measures to be placed on the November ballot. Two of the questions deal with city government administration, and the third asks voters whether the party primaries should be replaced with nonpartisan elections.

City Purchasing

In one question, voters are asked to approve a measure that would simplify the way the city handles the purchase of goods and services. It includes provisions to expand opportunities for minority-owned and women-owned businesses, and it seeks to streamline procedures for purchasing methods, while increasing qualifications for city purchasing officials.

Government Administration

This question addresses the issue of mayoral authority in the governing of administrative law judges and hearing officers in the city's administrative tribunals. It would expand the authority of the administrative tribunal at the Department of Consumer Affairs, and it would increase the authority of the Conflicts of Interest Board.

City Elections

This is by far the most controversial question and will be the most hotly contested. The question is whether New York City should abolish party primaries and instead hold nonpartisan elections, in which anyone can run and anyone can vote, regardless of party enrollment or affiliation. The September primary would become an open election in which all candidates run together, and the November election would be the run-off between the top two candidates for each office. This would affect all city elected offices, including mayor, public advocate, comptroller, borough president, and council members. If it is passed, it would not take effect until after the 2005 elections, meaning none of the current elected officials would be affected by it.

Voter turnout in primary elections is typically low, and this year will not be an exception. But this year the primaries may take on special significance as voters look ahead to the November elections, and a ballot question that could potentially represent the biggest change in New York City elections in over a century.

Susan Reefer is a Republican pollster and media strategist. She is based in New York City.

Citizenship and Voting

Â

Race and Citizenship Status in the Voting Age Population (New York City, 2000)

Source: 2000 Census 1% Public Use Microdata Sample |

Tejeda grew up in Washington Heights, graduated from the Fashion Industries High School in Manhattan, and when Mayor Michael Bloomberg spoke at his funeral, the mayor said, "We are proud he was a citizen of New York."

But Tejeda, who was born in the Dominican Republic, was not a legal citizen of the United States. And while he was willing to fight and die for his country, he could not vote in it.

Over a million New York adults are in the same situation. In recent years, some immigrant rights advocates and politicians have been quietly working to win voting rights for non-citizens.

This week, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's Charter Commission will reportedly formally announce its intention to ask Governor George Pataki and the New York State Legislature to allow green-card holders who live in New York to vote in local elections.

In the New York State Assembly, there is pending legislation that would extend the right to vote to non-citizens who have acquired permanent status and have applied for citizenship.

Proponents argue that immigrants have jobs, pay taxes, and contribute to society and should be allowed to elect their local representatives. Opponents counter that legal citizenship is essential to understanding and participating in democracy.

But for all of the debate, non-citizen voting is not a new idea in New York City. Until this year when the city's education system was reorganized, immigrants with children in the city schools could vote in local school board elections, whether or not they were legal citizens of the United States.

If non-citizen voting was extended to other local offices such as district leader, City Council, and mayor, experts say, it could radically alter politics and even government in New York.

ARGUMENT FOR NON-CITIZEN VOTING

Proponents of non-citizen voting rights argue that immigrants share many of the same responsibilities of citizens and should be given the right to vote. Immigrants pay taxes, send their children to public schools, and can even serve in the U.S. military. Nationally, 37,000 members of the active-duty military - nearly three percent - are non-citizens.

"Taxes are being withheld from [non-citizen] salaries to support city services," said Margaret Fung of the Asian American Legal Defense Fund.

Local government would be more representative of the city, advocates claim, if a million non-citizen New Yorkers could elect their representatives. It was not until 2001 when term limits kicked out many long time incumbents in New York City, that the first Asian American was elected to office, even though Asians comprise 10 percent of the city's population.

It can also often take a decade or more for legal residents to be granted citizenship because of a cumbersome naturalization process.

"Most immigrants want to become citizens," said Borough of Manhattan Community College Professor Ronald Hayduk, who has written extensively on the subject of citizenship and voting rights. "It's just that it takes forever."

Another argument is that the notion of citizenship has been fluid throughout U.S. history.

"For a long time the whole process of becoming a citizen was in local hands and had much less bureaucracy than it does now," said John Mollenkopf, director of the Center for Urban Research at the City University of New York. "A local judge could declare you a citizen if you'd lived here for five years and kept yourself out of police trouble."

Other areas of the country, such as Takoma Park, Maryland and Cambridge, Massachusetts, have already passed measures allowing non-citizens to vote.

ARGUMENT AGAINST NON-CITIZEN VOTING

Opponents argue that immigrants already have a way to vote - by becoming a citizen.

To become a legal U.S. citizen, a person has to be a legal permanent resident for at least five years. He or she must also be able to speak, read, and write in English, and demonstrate an understanding of U.S. history and government.

These things are essential, say opponents of extending voting rights, to understanding and participating in the democratic process. "There are certain rights and privileges that come with being a U.S. citizen - and the right to vote is central," said Republican City Councilmember James Oddo.

If voting rights were offered to those who have not taken the time or effort to earn citizenship, it would undermine the significance of voting and what it means to be an American.

"People who are here for three years or five years and who are given the right to vote would have little incentive to go through with the naturalization process," said Stanley Renshon, a professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, who has authored a book entitled "The 50 Percent American: National Identity in a Dangerous Age."

Renshon also rejects the notion that non-citizens are not benefiting from paying taxes. "The idea that they pay taxes but are getting nothing for it is an absurd affront," he said. "Obviously there are benefits in coming to this country and that is why people do it."

Some opponents acknowledge that while the citizenship process is imperfect, giving people the right to vote is not part of the solution.

And there are efforts to speed up the process of becoming a citizen for military personnel, who have demonstrated their commitment to the country. Spurred by the deaths of 10 immigrant soldiers like Riayan Tejeda, Congress recently passed a bill to reduce the time from three years to one year that an immigrant member of the military must wait to become a U.S. citizen.

HISTORY OF CITIZENSHIP AND VOTING IN NYC

Initially, the right to vote in the United States was not based on national citizenship, but on race, gender, and the ability to pay taxes.

In 1777, the New York State Constitution allowed men to vote if they owned twenty-pound freeholds, paid two pounds a year in rent, or had been admitted as freemen of New York City or Albany.

New York was one of the first states in the nation to require U.S. citizenship in order to vote, according to Hayduk. In 1804, the state's election law was changed to require national citizenship, though this requirement was never explicitly included in the state constitution. Most other states did not require citizenship until around World War I.

The decision to tie voting rights to citizenship, argues Hayduk, resulted from rising patriotism during wars, but also a general fear of immigration and its effects on the political system.

"Mass immigration contributed to controversy about the impacts of immigrants on everything from labor markets and wages, crime and public morals, electoral outcomes and public spending," said Hayduk, "to notions of race, ethnic and national identity."

In recent years, lawmakers in Albany have introduced legislation that would speed the process of non-citizen voting. In 1997, Brooklyn Assemblyman Vito Lopez introduced legislation to give non-citizens the right to vote if they lived in the state for five years. That bill was defeated, but two subsequent bills were also introduced.

This year, New York State Assemblyman Nick Perry, an immigrant from Jamaica, introduced a bill that would extend voting rights to permanent residents who have lived in New York State for at least three years and have filed an application for citizenship. He first introduced the bill in 1993 and says lawmakers must continue to push the issue.

"I am hopeful at some point the anti-immigrant sentiment will be overcome by realization of the fact that immigrants are builders and part of the American foundations," Perry said.

COMMUNITY SCHOOL BOARDS - A CASE STUDY

In recent years, non-citizens have played an important role in the local political process.

Between 1969 and 2003, non-citizens who had children in public schools were able to vote in elections for members of community school boards. The school boards were eliminated in 2003 as part of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's reform of the education system.

Community school boards were often criticized for being ineffective and overly political and voter turnout was low. But proponents of extending voting rights to immigrants say that the problems of local school governance had nothing to do with who was voting.

The local school boards were also more ethnically diverse than any other branch of government in New York; in 1999, for example, 15 Asian Americans were elected to the 32 school boards.

"Non-citizens parents proved that people who have a stake will participate," said Hayduk. "Community school boards were not perfect, but in terms of their power, they selected superintendents and allocated funds - things that matter. They were symbolically, if not substantially, important."

CHANGING THE CITY

If non-citizens were given the right to vote, politics and government in New York no doubt would change.

"Of the roughly 5.5 million people who are of voting age in New York City, about a million are non-citizens," said John Mollenkopf. "Elected officials would pay a lot more attention to the needs of groups they can now safely ignore."

The biggest difference would come for Dominicans and Chinese immigrants, who currently comprise the largest percentage of non-citizens adults in New York. (See chart for citizenship by race.)

And issues like bilingual education, health care, access to city services, and even the budget process would change.

"I think the question is not necessarily that you will get all the services that immigrants might prefer," said Margaret Fung, "but the point is that they would have a voice, so that when the budget is being adopted that at least there would be some consideration of some of the needs of immigrants."

The recommendation from Mayor Michael Bloomberg's Charter Commission to allow non-citizen voting will be met with opposition from Republican lawmakers in the city and state.

"I think it is becoming more and more apparent that the Charter Commission is a political tool for a political agenda," said Republican City Councilmember James Oddo. "This is a calculated position to curry favor with a particular group."

Some Democratic lawmakers are also suspicious because non-citizen voting is being tied to the commission's other goal of instituting non-partisian elections and eliminating party primaries, an idea that most Democrats oppose.

"This is a hypocritical action," said Lower East Side Councilmember Margarita Lopez. "Something as serious as voting rights should not be matched up with anything else."

There are also legal questions about the issue since the state election law says U.S. citizenship is a voting requirment, but the New York State Constitution does not.

Charter Commission Chair Frank Macchiarola reportedly has already approached the mayor's office and the City Council about working to pass the measure.

"The commission thinks indeed that voting by non-citizens would go to the heart of the objectives of the commission, which is to increase access and participation with local government across the board for all New Yorkers," a spokesman said.

New York City Council STATED MEETING - August 19, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - August 19, 2003

Quote of the Day:

"James, you are doing it now, man. I got calls from Egypt, from Bogota, Colombia, from England. All over the world, they are talking about you, James. All over the United States, all over the city, they are talking about you. There is a divine purpose for this moment." - Councilmember Charles Barron on the life and death of James E. Davis, who was shot in City Hall in July.

Meeting Summary:

The New York City Council met for the first time since Brooklyn Councilmember James E. Davis was shot to death in City Hall last month.

In tribute, Davis's desk in the City Council chambers was draped with an American flag and constituents held up signs with his photograph in the balcony where the shooting occurred. Davis's family, including his mother Thelma, and brother Geoffrey, who is now running for the open seat, also attended.

Davis, who was elected to Brooklyn's 35th district council seat in 2001, was a former police officer, and the chair of Stop the Violence, a non-profit organization, which he founded in 1990. Davis also fought against youth violence, child abuse, and police brutality, winning widespread media attention for his efforts.

He was also known for his sense of humor, his love of the spotlight, and, at times, his independence in voting against the party and council leadership. Council members spent the first hour and a half of the meeting recounting memories of their colleague.

"James lived his life in pursuit of a better, safer world for our children, and that is a legacy that we all should be dedicated to continuing," said Council Speaker Gifford Miller.

Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum recalled her usual ritual of greeting Davis, which consisted of a hug, a high-five, and a laugh. "I realize how much that ritual meant to me and how much I miss him," said Gotbaum.

Republican Councilmember James Oddo talked of how Davis even made the "Minority Leader's Hall of Fame" - a collection of photographs in the office of party that has only three representatives and loses every controversial vote in the council - when the Democrat Davis voted with the Republicans against the 18.5 percent property tax in 2002.

Security in the council chambers was increased after the July 23 meeting when political rival Othniel Askew shot Davis. Askew, who bypassed metal detectors as he entered City Hall with Davis, was fatally shot by a police officer. There were more police officers on the council floor and everyone entering City Hall, including council members and their staff, had to pass through a metal detector.

The City Council also voted on legislation held over from the day of the shooting.

The council approved a street furniture bill (L.U. 226-A and Res 1004) that makes way for the construction of bus shelters and public pay toilets that will be funded by advertising placed on the sides of the structures. Under this legislation, new public pay toilets will be handicap accessible and must be approved by the Department of Transportation, the community board, the council speaker, and the mayor. Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff estimates that the legislation could generate up to $400 million in revenue for the city over the next 20 years.

The council also passed a bill (Intro 399-A) that creates an Adopt-A-Park program for the city. Individuals, community groups, or corporations will be allowed to donate money and volunteer time to the park of their choice.

Another bill (Intro 410) reduces the amount of time an elderly New Yorker must wait to apply for senior citizen rent increase exemption benefits. Under the existing law if a person loses income - for example if a spouse dies and their pension payments end - an individual may have to wait up to a year to apply for the program that helps low-income senior citizens pay their rent. The new law allows a person to apply immediately.

All of the measures passed unanimously (by a vote of 44 to 0, with six council members absent), with the exception of a bill (Intro 509) establishing a Business Improvement District in the downtown Flushing transit hub. Queens Councilmember Allan Jennings voted against the measure, but did not return phone calls for comment.

The City Council also passed a resolution that Councilmember Davis was going to introduce the day he was murdered. The resolution (Res 983) calls on the New York State Department of Labor and Health Hazard Abatement Board to "promptly implement meaningful and enforceable safety standards in order to prevent violence in the workplace."

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for September 17, 2003.

For more on the race to fill James Davis's seat in the council, visit the Community Gazette page for district 35

Post your comments on the James E. Davis message board

For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.

Â

After The Blackout - Going Back To The Experts

Three days after we first posted our article ("Studying How To Avoid Blackouts") about the effort Con Edison was making to avoid blackouts in New York, New Yorkers were among the victims of the largest blackout in the nation's history - and it had nothing to do with the research Con Edison was conducting.

At its new center in the Bronx, as the article explains, Con Edison is doing research intended to help prevent localized power outages, like the one in Upper Manhattan in 1999, which was caused by a cable failure in Con Edison's local distribution network.

The power outage on Thursday, August 14, was of another scale and magnitude altogether -- and demonstrated just how vulnerable local utilities, including Con Edison, are to the collapse of regional transmission systems. The blackout swept across eight states and parts of Canada and the Midwest within seconds -- even though steps taken after the blackout of 1965 were meant to safeguard against just such an event.

"What happened on Thursday was beyond Con Edison's territory," said Con Edison spokesperson Chris Olert by e-mail. "One of the reasons Con Edison shut down was because generators shut down: Without the power, Con Edison has nothing to distribute to customers."

Following the deregulation of the industry in the 1990s, Con Edison no longer generates power, but is responsible only for distributing it throughout New York City and parts of Westchester. According to Con Edison, there was no damage to its system, which shut down automatically as it was designed to do to prevent overloading.

"For some reason, some transmission lines got overloaded, and they tripped out. And for some reason, the outage was not contained to an area where it should have been contained, and that's part of a whole investigation as to why did that happen." said Luther Dow, director of Power Delivery and Markets at the Electric Power Research Institute when contacted again three days after the blackout.

While the exact cause of the massive power outage is not clear as of this writing, early inquiries suggest three failed transmission lines in Ohio may have triggered a domino effect which left some 50 million people without power. According to the North American Electric Reliability Council, a massive power swing just before the lights went out at 4:11PM that afternoon may have caused generators throughout the region to automatically shutdown -- including the power plants that supply Con Edison.

In the original story, we noted that industry rating groups say Con Edison's system is the most reliable in the country. "Because of the way the system is laid out and the maintenance, it is by far the most reliable system. No one even comes close to them," Walter Zinger, an electrical engineer with the Electric Power Research Institute told us. And, Mayor Bloomberg defended the utility's handling of the outage in a press conference Friday. "I think [Con Edison] actually did a good job. I am sure they could have done some things better," he said. According to the mayor, the utility was delayed in bringing the system back on line by problems with other utilities upstate.

Maybe so, but Con Edison's system was affected along with the rest of the region. And city and state officials, including Bloomberg, are demanding an investigation into what caused August 14th's cascading failures. Weren't steps taken after 1965 to prevent local outages from affecting the entire region? What safeguards were in place to protect the city and state from regional power failures, they and others want to know, and why did they fail?

"We have to take a look and see why a problem someplace outside of this part of the power grid caused so much chaos within it. It wasn't supposed to happen," said the mayor.

CRITICAL PRESCIENCE?

"I think Con Ed is sitting in this category of utilities that have been disinvesting in both the physical infrastructure and the human infrastructure with regards to transmission," State Assembly Representative Paul Tonko told us when we first reported this story. Concerned about bottlenecks in the regional system, he and Jason K. Babbie, a policy analyst with the New York Public Interest Research Group, urged Con Edison to look at new and more efficient transmission technology, including super conductivity cables, to open up the city's power market and keep costs down. How prescient they were, though not necessarily for the right reasons.

In the original story, we also cited a study released by the New York State Energy Planning Board in 2000 found that capital investments in the power transmission system declined dramatically from 1988 to 1998 (from $304.4 million in constant 1998 dollars to just $90 million), but that reliability appeared to be unaffected.

"All the analyses performed lead to the conclusion that New York State's transmission system has operated in a highly reliable manner. Further, New York's bulk transmission system is improving in its ability to weather severe disturbances," the report read.

"That was a troublesome notion back then, and it is now. It's taken on new relevance with all that's happened here," said Tonko when we talked to him again after the blackout. "I am of the belief that no major investment has been made on the transmission side in the private sector since the 1960's, and in the public sector since the 1970's. But demand has grown tremendously, and we've been putting an overwhelming strain on the system."

Tonko also worries that, following deregulation, responsibility for maintaining the state's transmission system and putting in place safeguards that might prevent failures in one part of the grid from affecting other parts of the grid is not clearly defined.

Con Edison says it is responsible for maintaining the high-voltage transmission lines it owns (as well as the local low-voltage cables we discussed). But according to Con Edison spokesperson D. Joy Farber, the New York Independent System Operator, which was formed in 1998 to manage the market for electricity in New York State after the industry was deregulated, is responsible for maintaining the state's transmission system as a whole.

Now Tonko's longtime call to invest in the nation's power transmission system is being echoed from officials at all levels. Speaking in California, President George W. Bush called the blackout "a wake-up call," and said the nation's electrical grid must be upgraded. Mayor Bloomberg has also called for investment in new transmission lines.

"Nobody wants to have a power line going through their backyard, but we have to face the issue that if you want to have electricity-and we really have no choice, we have to have electricity, our society depends on large amounts of electricity and it has to be reliable-that means building power plants, upgrading power plants and building transmission lines," the mayor said over the weekend.

As for the cable center, although Thursday's blackout is unrelated to the more locally-oriented, low-voltage research Con Edison is conducting in partnership with the Electric Power Research Institute in the Bronx, Dow said the institute was in the process of forming a similar center to study transmission cables which would be based at its facilities in Lenox, Massachusetts. Its researchers have helped scrutinize data after major power failures in the past, and he said, would do so again if called on.

"There are hundreds of thousands if not millions of pieces of data that are going to have to be analyzed to put together the whole problem," Dow said, "and so that's what the industry will be doing over the next few days."

Executive Order 34 Revisited

Zhang Kui, an immigrant from Fujian, China, was asked to assist a New York City Police murder investigation in the Fifth Precinct in Chinatown. According to a report by the Chinese newspaper Singtao Daily, the police later found that Zhang is an undocumented immigrant and reported him to the federal immigrant agency, where he is now facing deportation.

Stories such as Zhang's are causing concern among immigrant rights groups who worry that Mayor Michael Bloomberg's executive order 34, which allows police, city agencies and services to ask people about their immigration status and then report them to the federal authority, will disrupt the lives of more than 400,000 undocumented immigrants in New York City.

Within days of the announcement, groups of immigrant advocacy groups and some public officials took to the streets to protest. Facing so much opposition, Mayor Bloomberg said in July that he is considering changing the order.

"Although the mayor believes on the merits it is a good order, he is considering revising it because of the harm its misconceptions have cause," said Edward Skyler, the mayor's press secretary. While the mayor is revising his new policy, some fear immigrants will continue shunning city services and refusing to cooperate with the police.

"[The new order] will radically change the city's relationship to its millions of immigrant residents," Moises Perez, executive director of Alianza Dominicana, who was in the protest at City Hall, told the Daily News.

In the past, an executive order issued by Mayor Edward Koch barred city employees from reporting undocumented aliens to immigration authorities. But in 1996, Congress passed a law stating that the city cannot forbid their employees from sharing information about an undocumented immigrant to federal agents.

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani refused to comply with the law and challenged its legality. In 1999, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the second circuit ruled that Koch's executive order was unconstitutional.

After the September 11 attack, the federal government encouraged local police to work with immigration agencies and allowed them to inquire about the immigration status of suspects. Under the new executive order, police can now report illegal immigrants to the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement

Since the court ruling, city officials have not clarified their policy toward undocumented immigrants. A few weeks before issuing the order, Mayor Bloomberg himself said on his weekly radio show that all undocumented immigrants should be made citizens.

The timing of the new executive order has to do with pressure from Washington to clarify the city's position on reporting illegal immigrants, according to a Daily News report.

As reported in this column two months ago, the City Council is now sponsoring a bill (Intro 326), "Access Without Fear" that would allow immigrants to get access to the city's health and social services without having to worry abut their status.

"In a city that is 40 percent foreign-born, it is essential that [immigrant] communities don't fear accessing city services," said City Councilmember Hiram Monserrate, who is the main sponsor of the bill.

An immigrant from Bangkok, Thailand, Chaleampon Ritthichai is the editor of The Citizen.

City Council Campaign 2003

Normally, few would have taken notice of the routine summer meeting about to begin on the City Council side of City Hall last Wednesday. Little girls in sashes and tiaras, veterans of the Bronx Puerto Rican Day Parade, were posing with plaques near the podium up front, one of several picture-ready ceremonies before the 51 members of the City Council took up the serious business of the day, the highlight of which was going to be a vote to approve the construction of 20 public toilets.

But then Othniel Askew shot and killed Brooklyn Councilmember James E. Davis, the first murder ever to take place inside City Hall. The murder brought national attention to the often overlooked branch of city government just months before all the council members must run for re-election.

It is a good bet that even most New Yorkers did not know that there were any political races coming up. But Othniel Askew certainly knew. He had hoped to run against Davis, and claimed he had collected enough signatures to make it onto the ballot, but told reporters he narrowly missed the deadline for filing the signatures with the Board of Elections.

As police continue to investigate the bizarre circumstances of this sensational crime, it is unclear whether (and, at this point, unlikely that) the murder will have anywhere near the same impact as the assassination in July 1881 of President James Garfield by a person always described as a “disappointed office seeker” -- which led to a complete rethinking of the process of staffing the federal government.

There are plenty of critics of the election system in the city who believe it needs to be rethought, and not because of violence -- although violence in city politics certainly exists. In 2001, a council candidate’s headquarters was set on fire and in another incident police had to break up a shoving match between rival campaign workers. Just two days after Davis was shot, a campaign worker for a challenger was arrested for threatening Queens Councilmember Hiram Monserrate.

But candidates are far more routinely battered by the frustration of simply trying to get onto the ballot, especially if they are challengers to an incumbent. Every campaign season, candidates go to court to knock one another off the ballot, with the most powerful and wealthy candidates backed by a team of lawyers. The Davis campaign, for example, though suddenly without a candidate, continued to challenge the signatures of a candidate for the seat, Anthony Herbert.

The race to succeed Davis is one of just 51 this fall, when across the city, some 165 people will be running for seats now largely occupied by one-term incumbents. The race in district 35, James E. Davis’s old seat, will certainly be the most watched campaign of the year (See article). But there are at least nine more races in which, political observers say, the outcome is not at the moment a foregone conclusion.

Some races to watch this fall are rematches of 2001, when the difference between the winner and loser was just a few dozen votes.

In the north Bronx, Shirley Saunders, who lost to Larry Seabrook by just 103 votes in 2001, is running again and challenging the record of the incumbent. “I think people have seen Larry Seabrook more over the last three months [campaigning] than they have in all of sixteen years,” said Saunders.

In other races, the incumbents have spurred the opposition by their personalities or actions.

Queens Councilmember Allan Jennings has earned a reputation as one of the most unpredictable members of the council, in the last two years comparing himself to Jesus Christ, placing newspaper ads pledging his love for a Chinese folk dancer, and calling Mayor Bloomberg a “dictator.” Jennings, who did not get the endorsement of the Queens Democratic party is facing five challengers this fall, but says he is not concerned: “I am still going to win."

And some races - although they have a personal and political component - are centered on issues that affect New Yorkers’ lives.

Cypress Hills, Brooklyn, for example, has the highest rates of childhood lead poisoning in the city and incumbent Councilmember Erik Dilan is one of just a few in the council who has not sponsored legislation to require landlords to clean up lead dust. His challenger, Nellie Santiago, says if she is elected she will work to get the bill passed.

Just how the murder of Councilmember James Davis will change this campaign season is yet to be seen.

Some say that the violent attack in the chambers of the City Council is bound to affect the candidates and their strategies. “Events like this make us feel vulnerable and distrustful, both for candidates and the citizenry,” said Scott Levenson, a political consultant.

But others say that unlike the terrorist attacks of September 11, which postponed - and overshadowed - Primary Day in 2001, this tragedy will not radically alter the political process. “In 2001, the very act of campaigning could be viewed as taking advantage of a tragedy,” said political science professor Douglas Muzzio. “This is a totally different set of circumstances. These candidates will run all out, full out.”

TEN RACES TO WATCH

The following are summaries of articles about ten races. The links take you to a district homepage on our Community Gazettes. Then click on the "Campaign 2003" button to take you to that district's campaign page.

District 10 - Washington Heights, Inwood

In an area of the city where rents are rising and affordable housing is scarce, three Democrats and a Republican are challenging incumbent Councilmember Miguel Martinez.

District 12 - Co-Op City, Baychester, Wakefield, Eastchester

A third of the population of district 12 and two Democratic rivals live in Co-op City, which represents the bulk of voters and the area’s major issues. Shirley Saunders, who only lost by 103 votes in 2001, is again challenging incumbent Councilmember Larry Seabrook.

District 18 - Parkchester, Castle Hill, Soundview

In the latest chapter in a long political rivalry in the Bronx, incumbent Councilmember Pedro Espada Jr. has dropped out of the race and handed his seat to his son Pedro G. Espada. A new challenger, backed by the Bronx Democratic Party, is hoping she can win.

District 27 - St. Albans, Hollis, Cambria Heights

The quiet middle-class neighborhoods of district 27 in Queens are home to much of borough’s trash. Garbage dumps - and what should be done about them - are a major campaign issue in this district where the challengers say the incumbent spends too much time at City Hall.

District 28 - Richmond Hill, Rochdale Village, South Jamaica

Councilmember Allan Jennings has earned the reputation as one of the most unpredictable members of the City Council. Five challengers and the Queens Democratic party are hoping to unseat him.

District 34 - Williamsburg, Bushwick, Ridgewood

The face of Brooklyn is changing as the waterfront is developed and trendy neighborhoods spring up. But the council member who represents district 34 will also have to listen to the concerns of residents of Queens, now that redistricting has changed the political boundaries of this area.

District 35 - Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Prospect Heights

Councilmember James E. Davis was shot dead by a political rival. This fall, residents will now have to choose someone to fill the vacant seat.

District 37 - Cypress Hills, Wyckoff Heights, Bushwick

This district has the highest incidents of childhood lead poisoning in the city, and the race centers on legislation to create tougher lead paint laws. The incumbent does not support it; the challenger does.

District 43 - Bay Ridge, Dyker Heights, Bensonhurst

Taxes matter a lot in this area, which is one of the few parts of the city ever to elect a Republican to the City Council. A Democratic incumbent, who has voted to raise several taxes since taking office in the spring, is hoping he can hang on to his seat.

District 45 - East Flatbush, Flatlands

A nondescript building in East Flatbush could determine the political future of City Councilmember Kendall Stewart. He owns the building and blamed recent violations on his tenants. His challengers say he is not serving the community.

New York City Council STATED MEETING - July 23, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - July 23, 2003

Meeting Summary:

Shooting at City Hall

New York City Councilmember James E. Davis was shot and killed at 2:08 p.m. on July 23, the victim of a gunman who opened fire inside the City Council chambers during the council's regularly scheduled meeting. Davis was shot by a political rival, Othniel Askew, who accompanied the council member to City Hall. Askew was shot by a plainclothes police officer and died later.

Askew, 31, reportedly entered City Hall as a guest with Davis and was able to bypass the metal detectors because he was with the council member. Askew and Davis met earlier in the day in Brooklyn then proceeded to City Hall, where Davis introduced Askew as a former rival turned friend. The two men went to the balcony before the beginning of the council meeting, where, according to police officials, Askew fired a 40-caliber handgun multiple times, killing Davis. A police officer on the floor of the council chambers then fired six shots at Askew, hitting him several times. Davis, a retired police officer, carries a handgun, but did not draw or fire his gun.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who was in his office at the time of the shooting, was unharmed.

Askew was planning on running for City Council against Davis this fall, had filed with the city's Campaign Finance Board, and had reportedly circulated petitions, but did not file them in time to get on the ballot. According to reports, Askew phoned the New York City Federal Bureau of Investigation office yesterday morning to report that Davis had been harassing him in connection with the upcoming primary election.

James Davis, 41, who was elected to Brooklyn's 35th district council seat in 2001, was a former police officer, and the chair of Stop the Violence, a non-profit organization, which he founded in 1990. Davis also fought against youth violence, child abuse, domestic violence and police brutality, winning widespread media attention for his efforts. In 1994, he helped stop the sale of "look-alike" toy guns following the shooting of two children by police officers who mistook their toys for real weapons. He also campaigned successfully to have MTV change its broadcasting policies, arguing that the network's former policies resulted in the broadcasting of excessively violent images and lyrics during the daytime. A graduate of Pace University, he also served as a Democratic district leader, working to register voters in neglected communities.

In an essay Davis wrote for Gotham Gazette, he recounted how he became politically involved: "One morning in 1983, I was in front of my house sitting in my mother's car. Suddenly, I was approached by two white police officers who accused me of stealing the car. The officers dragged me from the car at gunpoint, slammed my head and body repeatedly against the car and pointed their guns inches away from my head. I was handcuffed and taken to the police station. No charges were ever filed, but that day, I suffered not only bruises, but also the humiliation of false arrest. Since that day, I have tried to turn that experience into something positive."

For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.

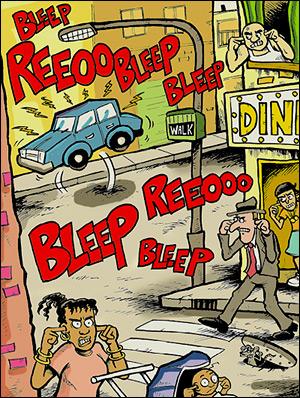

The Case Against Car Alarms

"A burglar alarm combines in its person all that is objectionable about a fire,

a riot, and a harem, and at the same time has none of the compensating advantages." So wrote Mark Twain in 1882.

"A burglar alarm combines in its person all that is objectionable about a fire,

a riot, and a harem, and at the same time has none of the compensating advantages." So wrote Mark Twain in 1882.

More than a century later, alarms have grown louder and migrated to cars parked in every New York neighborhood, and no one is any fonder of them. Councilmember Eva Moskowitz (D-Manhattan) says "the most frequent noise complaint" from her constituents is about car alarms. Now she and Councilmember John Liu (D-Queens) are each sponsoring a bill that promises to solve New York's car alarm problem.

Liu's bill, introduced in 2002 with nine co-sponsors, would ban the sale and installation of audible car alarms in New York City. Moskowitz's bill, introduced in April with fifteen co-sponsors, would go further, banning the sale, installation, and use of the alarms. Moskowitz also proposes a mechanism for citizens to report annoying alarms to the police, prompting a warning letter to the car owner.

It is clear that these bills have the full support of New Yorkers. In a survey conducted earlier this year by Transportation Alternatives (whose results are published as part of a report I co-wrote, Alarmingly Useless: The Case For Banning Car Alarms In New York City ), three-quarters of the 800 New Yorkers who responded said that car alarms interfered with their sleep; 90 percent said that alarms diminished their quality of life. Many spoke passionately: "This is one of the annoyances that rises to the attention even of life-long New Yorkers like me," one said, typically. "I don't hear fire engines, but I do, painfully, hear these car alarms -- while I'm sleeping, when I'm trying to read or think or just live. They're all useless, loud, and extremely disruptive."

And useless they are. The only unbiased study ever done on the subject -- one conducted by the insurance industry -- shows that car alarms do nothing to stop car theft.

But when a version of Liu's bill was introduced in the City Council in 1997, lobbyists for the car alarm manufacturers derailed it.

Not surprisingly, these manufacturers are once again trying to convince the City Council not to ban their product. At a recent council hearing on car alarms, Directed Electronics spokesman K. C. Bean said, "The proof that our systems work is exhibited in the fact that since 1993, annualized vehicle theft in New York City has fallen by 76 percent." Of course, crime is down across the board; during the same period, New York City's murder rate dropped by 70 percent, and robberies by 68 percent. Car theft rates would probably have dropped dramatically too, with or without alarms. But this statistic was the only "proof" any of the manufacturers were able to cite.

At that same hearing, the New York Police Department also decided to oppose the car alarm ban. Its reasoning was hardly better than Bean's. Assistant Commissioner Susan Petito said New York should permit car alarms because "we can't know for sure whether audible alarms deter car thefts." Apparently, the NYPD has never seen the insurance data. When pressed, Petito admitted that the department has no evidence that alarms work, keeps no statistics on the arrests (if any) that car alarms have led to, and knows that police officers themselves usually ignore the alarms.

In fact, the department put out a booklet in 1994, "Police Strategy No. 5," of which the assistant commissioner seemed to be unaware. The police pamphlet called car alarms an "annoying and sometimes unbearable disturbance for residents in their homes." They "frequently go off for no apparent reason." And as one of the "signs that no one cares," they "invite both further disorder and serious crime."

The truth is, there is no reason to allow car alarms to continue in New York City -- and many reasons to ban them.

CAR ALARMS ARE HARMFUL TO OUR HEALTH

A recent Cornell University study finds that traffic noise raises blood pressure, increases stress hormones, and leads to "learned helplessness" in schoolchildren. Many traffic sounds contribute to the problem, but car alarms, unpredictable and often exceeding 125 decibels, can be especially harmful. The World Health Organization warns that even for those who think they can "tune out" or ignore the noise, physical tests show otherwise. "There [are] increased levels of stress hormone and elevation of resting blood pressure."

Children bombarded with car alarm noise suffer even more. A noisy environment makes sleep and concentration difficult, and can interfere with language acquisition. Noise analyst Arline Bronzaft's famous study in a Manhattan elementary school found that children in classrooms facing noisy, elevated subway tracks read as much as one grade-level below their counterparts in quiet classrooms. Another study by psychologist Sheldon Cohen examined an apartment building overlooking the George Washington Bridge, and found that children living on lower, noisy floors did not read as well as those on the quieter, upper floors. The experts believe that children exposed to loud traffic noise learn to ignore sound cues, which makes it harder for them to pay attention in class.

Car alarms also contribute to a break-down in civility among neighbors. In a series of psychological studies beginning in the 1970s, researchers "accidentally" dropped books on the sidewalk and measured how often passersby offered to help pick them up. In normal conditions, 80 percent of the pedestrians offered help. With an 87 decibel lawnmower blaring nearby (about half the volume of an average car alarm), only 15 percent of passersby offered their assistance. Loud noise, as later research confirmed, makes people less attentive to the needs of their neighbors.

Perversely, then, alarms alienate the very neighbors that car owners depend upon to call the police when their alarms go off.

CAR ALARMS DON'T STOP THEFT

In 1997, the insurance industry's Highway Loss Data Institute looked at insurance claims data from 73 million vehicles, to see which devices could prevent theft. While new vehicle immobilizers cut theft rates in half, the study concludes that cars with alarms "show no overall reduction in theft losses" compared to cars without alarms. The alarms just don't work.

"An audible system is really just a noisemaker," explains General Motors spokesman Andrew Schreck, who notes that only eight percent of GM's light duty vehicles now have an alarm as standard equipment. "Most people, when they hear an alarm, they just walk the other way."

There are two main reasons that car alarms don't work. First, people know that the vast majority of blaring car alarms are false alarms, set off by passing trucks, electrical malfunctions, or nothing at all. So no one responds to them -- often, not even the car owners themselves. A recent survey by the Progressive Insurance Company found that fewer than one percent of respondents would call the cops upon hearing a car alarm. In 1992, Darrell Issa, the multimillionaire founder of car alarm manufacturer Directed Electronics (who now leads the recall drive against California Governor Gray Davis), told the New York City Council that an alarm is effective "only in areas where the sound causes the dispatch of the police or attracts the owner's attention." In New York City, this just doesn't happen.

Second, alarms are very easy to disable. About 80 percent of stolen cars are taken by professional car thieves, and they know how to deactivate an alarm in just a few seconds, according to police and criminologists. "No one has demonstrated that alarms are effective," says Rutgers criminology professor Michael Maxfield, now studying car theft for the state of New Jersey. "No one seriously recommends them as a serious protection against theft. They might help a small bit, but there's a good reason why actuarial data show no benefit [to having an alarm]."

How to get New York car owners to switch over to effective -- and quiet -- anti-theft devices like vehicle immobilizers, tracking systems, and silent pagers, which do not cost any more than noisy car alarms? The Council can pass a ban on the old, ineffective, and unbearably noisy ones. The two bills under consideration would, in fact, help everyone here: local installers, who will be hired to change cars over to silent security devices; car owners, who will benefit from better security and bigger insurance discounts; and the millions of New Yorkers who wish, once in a while, to get some sleep.

Aaron Friedman is founder of Silent Majority: Citizens Against Car Alarms, and is a consultant to Transportation Alternatives.