New York City Council STATED MEETING - October 15, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - October 15, 2003

Quote of the Day:

"It seems as if the city has turned the corner fiscally." - Council Speaker Gifford Miller responding to news that there is an unexpected $110 million surplus in the city's 2003 budget.

Meeting Summary:

On October 15, the New York City Council passed a bill (Intro 569-A) giving the city the power to place advertising on newsstands, to require that the stands meet uniform standards, and to build bus shelters and public pay toilets.

"This is will totally revamp and revolutionize the way New York City administers street furniture," said Speaker Gifford Miler. "It will provide the city with a new aesthetic framework for our streets and sidewalks and will also raise substantial revenues through the sale of advertising space."

The city hopes advertising will generate $400 million over the next 20 years.

Newsstand owners and some advertisers opposed the plan, arguing that it would take away space on the outside of the stands and make it more difficult to attract business.

"For many distressed operators, who are already under tremendous pressure from half-priced subscriptions, street hawkers, and internet cigarette distributors, this will be the last straw," said Steve Stollman, a former newsstand operator.

The City Council members said compromises were made in the legislation to address some newsstand owner concerns. For example, it ensures that current stands cannot be closed or moved for at least six years. The bill passed by a vote of 45 to 3 (3 members were absent). Council members Allan Jennings, Hiram Monserrate, and Charles Barron voted "no." Barron said some of the advertising revenue should be shared with newsstand owners and said the plan favored the "fat cats over the little cats."

The council also unanimously approved legislation (Intro 262-A) mandating air conditioning on all buses and vehicles used to transport children with disabilities to school. Corona Councilmember Hiram Monserrate, who was upset that his 7-year-old son with autism was forced to ride a bus on 100-degree days, authored the bill.

"No child should be subjected to heat and illness to get to school, especially those with limited ability to communicate their needs," said Monserrate.

The council also passed several budget modifications, including one that transferred a surplus of $110 million from fiscal year 2003 into a new account. The unexpected money resulted because tax revenue was higher than expected.

Speaker Gifford Miller said that the additional revenue along with other positive financial reports signaled that New York City's economy is rebounding.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently ordered on all city agencies, except the Department of Education, to cut funding three percent. Miller said he wanted to use the additional revenue to limit budget cuts and said he hopes to reduce property taxes for senior citizens on fixed incomes.

"It is time to move away from budget cuts that will further curtail vital services," said Speaker Miller.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for October 30.

For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.

Learning from L.A.

The current gubernatorial recall election in California provides further ammunition for those who like to dismiss the West Coast, and especially Los Angeles, as offering little more than a comically surreal contrast to a real place like New York. But there are actually some striking similarities between America's two largest cities, and there are ways in which each can learn from the other's errors and innovations.

The current gubernatorial recall election in California provides further ammunition for those who like to dismiss the West Coast, and especially Los Angeles, as offering little more than a comically surreal contrast to a real place like New York. But there are actually some striking similarities between America's two largest cities, and there are ways in which each can learn from the other's errors and innovations.

The most publicized example of New York's influence on Los Angeles is the hiring of William Bratton to be L.A. police commissioner in the hopes that he will repeat the success he and others had in fighting crime while he was police commissioner in New York. But the flow need not go in only one direction. There is plenty that New York can learn from Los Angeles.

MORE DEMOCRATIC "NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCILS"

The City of Los Angeles adopted a new charter in 2000 and during the four years of debate preceding adoption two New York modes of governance were considered. The strong mayoralty model was vehemently rejected. New York community boards, on the other hand, were accepted, though quietly and in a somewhat different form - a form that could be instructive to New York.

On the strong mayoralty, then-Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan wanted the ability to appoint and fire department heads without City Council approval in the same way as New York's commissioners serve at the mayor's pleasure. Opponents in Los Angeles heatedly resisted giving the mayor such powers, arguing that to do so would vastly increase the possibilities of what they termed "New York-style" political corruption and mayoral abuse of power.

On the other hand the new Los Angeles charter adopted, and largely copied, one of New York City's most fascinating innovations, community planning boards, which in the form introduced into Los Angeles were called "neighborhood councils." The impetus for introducing these neighborhood councils in Los Angeles was the powerful San Fernando Valley secession movement (similar to the 1993 Staten Island secession movement), which, had it succeeded, would have taken 36 percent of the population out of the city of Los Angeles to become the sixth-largest city in the US, comprised of about 1.35 million people. So the secession stakes were high. It was felt in Los Angeles that neighborhood councils, by promising some local autonomy to neighborhoods, would undercut secession, and New York's community boards were the only existing model for such an experiment in any large U.S. city.

In both cities, the neighborhood councils/community boards are strictly advisory. In Los Angeles it was felt, for example, that there would be no way of avoiding the "not-in-my-backyard" problem if neighborhood councils were given decision-making powers. (In a bold move, though, area planning commissions were created in Los Angeles that do have some land use powers.) But beyond that basic similarity, Los Angeles's neighborhood councils differ in two significant ways from New York's community boards, making them more democratic. In Los Angeles, needing to start from scratch with no pre-determined boundaries, it was left to the people from each neighborhood to determine the geographic boundaries of each council, in a process that included some basic specifications, but that gave a startling amount of decision-making power to the communities themselves.

A second difference from New York is that in Los Angeles the officers of the neighborhood council (once its geographic boundaries have been approved), are elected by the residents of the neighborhood. In New York, by contrast, the fifty members of each community board are appointed, half by the borough president, the rest by the city council members within whose district the board's boundaries fall.

As the city of Los Angeles moves along with this experiment, it might be time for New York City to look more closely at its own experiment with community boards.

This closer look seems especially appropriate at a time when political parties, the main mechanism for citizen participation in the local political process, continue to lose effectiveness. Mayor Michael Bloomberg's proposal to introduce non-partisan elections in New York (a system that already exists in Los Angeles, by the way) may or may not succeed, but if it does succeed, it will leave community boards to play a greater role as links between ordinary citizens and political power.

AN ECONOMIC POLICY FAVORING SMALL BUSINESSES AND "MULTIPLE DOWNTOWNS"

On economic policy, a widely discussed study published recently by the Center for an Urban Future, urged New York City to follow the example of Los Angeles, and other cities such as Houston, which have acknowledged that in the last 20 years, a majority of jobs nationwide have been created by companies that employ fewer than 100 people. L.A. has encouraged the growth of small and medium sized businesses, often owned by minorities or immigrants, and successfully rebuilt its economy in this way. The report chided New York City for its "doomed strategy" of heavily subsidizing, via tax abatements and real estate abatements, a few large firms in select industries such as finance, insurance and real estate, in an attempt to prevent these firms from leaving the city for the suburbs. Such unfair subsidies drove up the price of real estate for small and medium sized businesses, and were also often ineffective in convincing the companies to stay. New York City was also urged to go beyond its traditional focus on Manhattan's midtown and downtown business districts, the first and third largest in the country respectively. Instead, the city should encourage multiple-downtowns fostering economic development in all five boroughs, for example in downtown Brooklyn, and in Flushing and Long Island City in Queens.

"Multiple-downtowns" sound like a version of the "edge cities" for which Los Angeles is famous, but modified for the needs of New York City. Edge cities, which have been developing over the last 30 years, challenge the traditional view that economic growth is concentrated in a central core downtown. Most urban regions are now made up of a multiplicity of edge cities (also known as "economic nodes") scattered around their entire geographic area. Formally, edge cities are defined as places that have substantial office and retail space, unlike the standard bedroom suburb. Some edge cities, especially in the Los Angeles region, are industrial districts. The New York region has many examples of edge cities (e.g. Melville and Hauppauge on Long Island and White Plains and Purchase in the rest of New York State, Woodbridge and Mahwah in New Jersey, and Stamford/Greenwich and Westport in Connecticut.) The obvious dilemma facing New York City as it moves to encourage economic growth in its outer boroughs is how to do this without seeing such development slide beyond the city borders.

Daniel Doctoroff, New York City's deputy mayor for economic development, said he agreed with most of the study and that the city was already implementing many of its recommendations, including cultivating business districts beyond midtown and downtown Manhattan.

LICENSE FOR IMMIGRANTS

New York City justly prides itself on its measures to guarantee services to immigrants regardless of their legal status, in sharp contrast to what is widely perceived as a deep anti-immigrant attitude in most of California. Nine years ago, for example, then-Governor Pete Wilson made support for Proposition 187, which excluded immigrants from receiving major social services, a major focus of his reelection campaign. However, on September 5 of this year, current Governor Gray Davis signed a bill allowing illegal immigrants to obtain California driver's licenses. This goes further than New York City, where residents whose immigration status is illegal cannot get driver's licenses.

The anti-immigrant movement in California has been undermined by California court decisions that invalidated most of Proposition 187, and by the passage of welfare reform on the federal level in 1996, which took some of the sting out of charges that immigrants were exploiting the welfare system. But it was demographics that pressured Davis to take a step to shore up his support. Latinos and Asians now comprise over a quarter of the state's population, the highest in the nation. It is no accident that the bill allowing California driver's licenses for illegal immigrants had been pushed since 1998 by a Democratic State Senator from the City of Los Angeles, Gil Cedillo. By 2000 the proportion of foreign born in the City of Los Angeles was 41 percent, which exceeds that in New York City (36 percent), the latter itself at its highest since 1910.

In short, this recall election signals that California's days as a bastion of anti-immigrant sentiment and legislation may be over, allowing for the emergence of the City of Los Angeles as an engine of pro-immigrant sentiment comparable to, and even in some respects outdoing, New York City. Defending his driver's license bill against those who said it was a security threat, Cedillo argued that the law would actually improve national security by placing on file at the Department of Motor Vehicles the fingerprints and home addresses of illegal immigrants. How long now before pressure mounts to allow illegal immigrants in New York to get driver's licenses too?

CRIME AND POLICING

Crime fighting is an area where the City of Los Angeles has decided, correctly, that it has much to learn from New York. In 2002 when Los Angeles surpassed New York City in the annual number of murders despite having a population (3.7 million) less than half New York's, the Los Angeles media and many politicians began to refer to Los Angeles in shame as the "murder capital of America."

In November of that year the Los Angeles City Council confirmed former New York City Police Commissioner Bill Bratton as Mayor Richard Hahn's choice to head the Los Angeles Police Department. Fighting crime, Hahn said, was the single most important issue on which his mayoralty should be judged. He added that provided crime fell he did not care if Bratton became the most famous man in Los Angeles (a reference to Mayor Rudy Giuliani having fired Bratton for becoming too visible).

Over the last eleven months Bratton has been implementing in Los Angeles many of the tactics he and others successfully adopted in New York City.

Bratton has also introduced some measures less familiar to New Yorkers. Risking the wrath of homeowners, he said that 92 percent of burglar alarms in LA are false, resulting in a huge waste of police time. The LAPD would no longer respond to home burglar alarms unless some human on the spot verified an actual problem. Bratton also pushed to end high-speed car chases. These, he said, jeopardized innocent lives in often ineffectual grandstanding for a live television audience.

But even in the area of policing, New York can learn some things from L.A.

The saddest example is probably the issue of helicopter rescue from tall buildings, raised acutely by the World Trade Center attack. Los Angeles is the only major city in the United States that requires all high-rise buildings to have helicopter pads on their roofs, and has elaborate plans and procedures, successfully implemented on several occasions, for rescuing people by helicopter from burning high-rise buildings. For about an hour-and-a-half after the first and second planes struck in New York on September 11, hundreds of people were trapped in the upper floors of the World Trade Center above the flames, unable or uncertain whether to descend by stairs, and calling for help on their cell phones, as recent transcripts in the New York Times revealed. Although police helicopters were hovering nearby, there were no helicopter landing facilities on the top of either tower and the doors to the roof were securely locked.

But what New York can best learn from Los Angeles is whether what happened to crime in New York City was some kind of fluke or whether there is truth to Bratton's theory that police reforms introduced by an energetic leadership can make a major difference in crime rates and police culture. Indeed, the causes of the drop in crime in New York City, as well as in America generally, have been among the most hotly debated topics in contemporary America. Bratton forcefully attributed the drop to new police tactics adopted while he was commissioner. Critics replied that since the number of murders in New York City was falling for two years before Bratton became commissioner, if anyone in city government is to get credit it should be then Mayor David Dinkins and his police commissioner Raymond Kelly. But these critics also questioned whether police tactics had anything much to do with the drop in crime, which they pointed out occurred in other cities where the New York Police Department's tactics were not adopted. They argued instead that demographics (especially a drop in the teenage population, which commits a disproportionate share of crime) and the decline in the crack epidemic were responsible for the decline in murders. Bratton and his supporters replied that the teenage population was not, in fact, declining in most of these cities including New York, and even if the number of murders was falling in New York City before Bratton became commissioner, it fell at a much faster rate after he took over. Others added that some of Bratton's reforms had, indeed, been introduced two years earlier by Raymond Kelly, which would explain why crime rates started to fall before Bratton began. Reflecting a view that the complete causes of the decline have not been understood, one of the recent studies of the topic was titled New York Murder Mystery.

Although it is still far too soon to be sure, the latest data from the City of Los Angeles are starting to support those who credit Bratton. By the end of August, 2003, homicides there had fallen 26 percent compared with the same time last year, from a total of 420 to 326. Further supportive of Bratton is the fact that in the rest of Los Angeles County -- the bailiwick of County Sheriff Boca, not Bratton and the LAPD -- homicides rose by 11 percent (to 217) during the same period.

HOLLYWOOD ON THE HUDSON

Though most of these examples show lessons that New York can learn from Los Angeles, the truth is, New York has already picked up plenty. The movie industry is a major example. The best New York film makers -- Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Woody Allen, Brian De Palma, Susan Seidelman, et al -- have showed, starting in the mid-1970s, that it is possible to "go Hollywood" while maintaining a Manhattan address.

Meanwhile, while Lincoln Center has scaled back its plans, Disney Hall, the new Frank Gehry-designed home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, will open this month, not in some well-to-do suburb but in the heart of downtown, and has attracted rock-concert-like lines to purchase tickets for Bach and Mozart.

David Halle is director of the UCLA LeRoy Neiman Center for the Study of American Society and Culture and adjunct professor of sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center. He is editor of the recently published New York and Los Angeles: Politics, Society and Culture.

Keeping the City Running

On the corner of Williams and Liberty Street, a new 30-story apartment building is going up, but before the luxury apartments are habitable, the

construction workers must go underground and rip apart the city's guts - electrical cables, water pipes, gas mains, and sewers lines, replacing the crumbling pipes with new ones.

On the corner of Williams and Liberty Street, a new 30-story apartment building is going up, but before the luxury apartments are habitable, the

construction workers must go underground and rip apart the city's guts - electrical cables, water pipes, gas mains, and sewers lines, replacing the crumbling pipes with new ones.

It is a precarious and disruptive project. Many of the old metal pipes are literally falling apart from years of rust. Workers with welding torches and saws crawl on their hands and knees through the tangle of pipes held up by ropes tied to wooden beams.

New Yorkers rarely think about the hidden systems that keep the city running, until a huge construction project gets in their way, a water main breaks, or until - like, most spectacularly, last August - the lights go out and everything shuts down.

"The blackout did not originate in New York, but people learned quickly that it affected everything," said Rae Zimmerman of the Institute of Civil Infrastructure at New York University.

When the electricity failed, thousands of commuters were trapped in subways. Residents who lived above the sixth floor of their apartment buildings could not get water. Sewage spilled into the city's waterways and shut down beaches. Cell phones failed.

But those who monitor the systems that keep the city running say it is not just events like September 11 or blackouts that pose a threat to the city. The biggest threat may be the everyday wear-and-tear on the city's systems.

There are thousands of potential hazards - most hidden from public view - that could paralyze the city.

In 1998, the City Comptroller released a 900-page report (in pdf format) detailing crumbling water mains, cracking sewers, and broken subway rails. The report estimated that it would take the city 10 years and $48 billion to get the roads, subways, water, sewers, and sanitation systems in working order.

At the time, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani dismissed the report as a "wish list" and said New Yorkers could not afford an increase in taxes. But others warn that New Yorkers can no longer afford to ignore the city's aging public works.

"These systems are critical for an urban environment," said Richard Anderson of the New York Building Congress. "It is absolutely essential that New York has reliable electricity, clean water, and working sewers."

ROUTINE REPAIRS

The city's infrastructure is old, with much of it being built 50 to 100 years ago. Just maintaining this system, which cracks and breaks every day, is a monumental task.

Every time a water main breaks - which happens more than 500 times a year - not only are workers from the Department of Environmental Protection called in, but also police, fire department, and transit officials. Multiple utility companies also must monitor their own lines.

This year alone, the city has received 1,300 complaints about faulty cable TV reception, responded to 3,000 sewer backups, and issued more than 18,000 permits for road construction.

Although repair workers can often fix the problem by climbing into one of the city's 600,000 manholes, which were invented as a way to minimize street disruptions, New York streets are constantly being torn up.

Accidental damage to pipes and cables by construction remains one of the most common reasons for power outages, telephone trouble, and water leaks.

PAYING THE BILL

The city's ability to meet its ongoing repairs and plan for the future is limited by government regulations and a lack of funding.

Most of the city's capital projects - fixing roads, repairing sewers, and building new water treatment plants - are funded by debt. State law restricts the amount of loans the city can take. For example, the city's General Obligation Debt, which will provide about $26 billion over the next 10 years, cannot exceed a specific percentage of the taxable real estate value in the city.

So the city seeks other funding, such as tobacco settlement money and state and federal aid. In the 1970's, when the city faced bankruptcy, many projects were simply delayed because of a lack of funds. This year, faced with another huge budget deficit, Mayor Michael Bloomberg cut the 2004 capital budget.

And for utilities like phones, gas, electricity, and water, customers pay the price to improve the systems in their monthly bills.

"There is a saying out there, 'do more with less,' but that is not how it works in the real world," said Jameel Ahmad, a civil engineer who teaches at Cooper Union. "I expect we will see an erosion of our infrastructure. Every budget has been cut, and things will get worse."

CRITICAL ISSUES

|

Roads And Bridges

A 2003 report card on New York's infrastructure by the American Society of Civil Engineers, cited roads and bridges as the top infrastructure concerns. According to the study:

- 30 percent of New York's roads are in "poor" or "mediocre" condition

- A third of New York's bridges are "structurally deficient" or "functionally obsolete"

- Traffic on New York roadways has increased by 21 percent over the last ten years.

And even when repairs are done, engineers say, they are not done correctly.

"New York City often mills the top surface of roadways when repaving. However they don't fix the base and subsurface and the problems keep coming back," one engineer wrote in the report. "On all highways within the city, everything a student is taught never to do is done."

Electricity

Con Edison maintains some 126,000 miles of cables, about two thirds of which are underground. And compared with the rest of the country, experts say Con Ed has one of the most reliable systems in the country.

"Because of the way the system is laid out and the maintenance, it is by far the most reliable system. No one even comes close to them," said Walter Zinger, an electrical engineer with the Electric Power Research Institute in a recent Gotham Gazette article.

Still there are over 2,000 power-line failures a year in the city and critics say that power companies are neglecting their old cables. A 2000 study released by the New York State Energy Planning Board found that capital investments in the power transmission system declined by nearly $200 million between 1988 to 1998

Deregulation - the loosening of energy regulations in the late 1990's that allowed for more competition between power companies - presents additional problems. For example, Con Edison must maintain its power lines, but the New York Independent Operator, a state agency that manages the energy market, is responsible for the whole system.

Experts say there is little economic incentive or will to build new transmission wires or upgrade systems.

Water

The city gets its 1.3 billion gallons of daily water from two tunnels that run from upstate reservoirs into the city. In 1969, the city began building a third tunnel to meet growing demand and to serve as a backup in case one of the other tunnels failed. Some fear the project will still not be finished by the year 2020.

Tunnel 3, which runs 60 miles and weaves through four boroughs, has been called "the greatest nondefense construction project in the history of Western Civilization." Already 24 people have died digging the tunnel - roughly a man for every mile built.

|

Some fear that the tunnels could collapse all at once, shutting down water to much of the city - if not all of it.

"There would be no water," Christopher Ward, the head of the city's Department of Environmental Protection, told the New Yorker magazine in a recent article. "These fixes aren't a day or two. You're talking about two to three years."

Because of the city's financial problems in the 1970's, construction on Tunnel 3 stopped for a decade and then proceeded slowly through the 1980's.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who has said that the "the city could be brought to its knees if one of the aqueducts collapsed," has increased funding for the Department of Environmental Protection, but other projects, like a new aqueduct and filtration plant, will consume much of the money.

Sewage

For the last ten years, the city's Department of Environmental Protection has spent 40 percent of its capital budget to upgrade the city's 14 sewage treatment plants. The city was required to do so by the federal Clean Water Act, which reduced the amount of sewage that could be released into the city's waterways.

But as the recent blackout demonstrated, not all of the systems are running smoothly.

When the electricity went out, backup generators at two of the city's fourteen wastewater treatment plants - Red Hook and North River - failed. And the 13th Street pump station on the East River does not have a backup generator even though the state issued an order to build one in 1995.

The result was that more than 490 million gallons of sewage spilled into the city's waterways, closing beaches and creating health and environmental hazards.

Telecommunications

As the terrorist attacks of September 11 and the recent blackout demonstrated, the city's telecommunications systems are susceptible to failure.

On September 11 2001, when 7 World Trade Center collapsed, Verizon lost an estimated 200,000 telephone lines and 3.5 million data circuits. Only one in 20 cell phone calls were connected. And emergency responders had trouble communicating.

Again during the August blackout, the top six cell phone carriers had unreliable service and landline systems were overloaded.

"The 9/11 attacks illustrated how fragile and poorly engineered our cellular communications system is," Anthony Townsend, a professor at New York University who specializes in telecommunications told CNET News. "It is incapable of dealing with crisis."

In an effort to create backup systems and lure high-tech business to New York, the city is converting unused water pipes under the city streets into conduits for fiber-optic cables.

However, the effort behind this resourceful idea diminished greatly with the dotcom bust. "Much of the fiber put down in the late 1990's was done haphazardly and some of those companies are gone now," said Townsend.

Sanitation

New York City generates more than 11,000 tons of garbage a day. For years, the trash went to the Fresh Kills landfill, but the dump closed in 2001.

Today, the waste is collected by nearly 1,500 sanitation trucks and transported to private waste transfer stations in the city and surrounding counties. There, most of the refuse is loaded onto 18-wheel trailers and transported to landfills in Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Residents in neighborhoods with a high number of waste transfer stations complain of heavy truck traffic through neighborhoods that cause noise, create pollution, and tear up local streets.

Meanwhile, the cost of disposing garbage has risen from $44 per ton in 1997 to over $88 per ton in 2001.

Public Transportation

New York has one of the most extensive public transportation systems in the world, which moves 2.4 billion passengers every year. Still it has been more than six decades since a new subway line has been built, in part because maintaining the current system is a monumental task.

"The top priority was, is, and will always be the maintenance and repair of the existing subway system," said Gene Russianoff of the Straphangers Campaign. "It is only in the last few years that our organization has come out in favor of expansion."

The MTA reports that subway tracks and switches are currently in a "state of good repair." The immediate focus is on renovating subway stations, which it hopes to complete by the year 2019.

Still the city is hoping to undertake several massive subway expansion that will tear up streets and cause disruptions to existing subway lines.

A new transportation hub in lower Manhattan will connect nine subway lines, the PATH train to New Jersey, and a high-speed link to Newark and John F. Kennedy airports. Mayor Michael Bloomberg has presented a plan for redeveloping the west side of Manhattan, which would include an extension of the 7-subway train. And despite lingering questions about how the city will pay for the project, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority is moving ahead with a plan for the Second Avenue Subway. The Second Avenue subway project would be the most disruptive to traffic and the existing infrastructure. The 8.5-mile line will stretch from 125th Street to Hanover Square in lower Manhattan and will not be completed until 2020.

MTA officials plan to use a technique known as "tunnel boring," using large drills to cut underground with less noise and vibration on the street. However, much of the construction would require underground blasting of explosives, which can cause damage to existing pipes and cables near the surface of the street. Some of the subway line requires a "cut-and-cover" technique, which requires opening the street, digging the tunnel, and then rebuilding all of the cables and pipes and resurfacing the street.

How the city will pay for all of these projects and how traffic would be rerouted for the next two decades is still unclear. "Some of these projects will never happen," said Russianoff. "There are finite resources."

PRICE OF NEGLECT

In 1988, the city paid a high price for years of neglect on the Williamsburg Bridge. The bridge was declared unsafe; merchants near the bridge complained that business was down because people avoided the bridge.

The city was faced with a choice:

- Permanently close the bridge, which would have caused traffic congestion on other bridges.

- Build a new bridge, which meant tearing down houses and building new roadways.

- Or repair the existing bridge.

The city decided that repairing it would be the least disruptive option.

Engineers estimated that if the city had done regular repairs over the bridge's 100-year history, it would have cost about $190 million in today's dollars. Instead it ended up costing more than $600 million.

These types of problems will occur again and again, experts say, unless the city plans ahead.

"No one is looking at the whole picture," said Anderson. "Each level of government deals with the short term and what they control. But looking at all of the systems as a whole, thinking in the long term, and finding adequate financing - those things are not being done."

A New Executive Order: Don't Ask, Don't Tell

While walking back home from work, Chris Un was harassed by two men who shouted, threw soft drinks and threatened to hurt him. Un thought about calling the police, but remembered that a friend from the consulate had warned him about a new crackdown on undocumented immigrants.

"I was afraid that the police were going to arrest me instead," said Un, a former student who had overstayed his visa.

These kinds of fears were why the city had not allowed the police and city workers to question anyone's immigration status. But that changed in May when Mayor Michael Bloomberg issued Executive Order 34 allowing the city's agencies, including police, to report illegal immigrants to the federal government.

Un is among many of the 400,000 illegal aliens in New York who came to believe that the order was an anti-immigrant measure.

After months of intense pressure from immigrant advocacy groups and the City Council, Bloomberg finally issued a new executive order in September.

Executive Order 41, dubbed as "don't ask, don’t tell," replaces Executive Order 34 and prohibits city agencies from inquiring or disclosing immigration status of New Yorkers who come into contact with city government.

"This gives assurances to all law-abiding New Yorkers… that the confidentiality of information you give to the city will stay with the city," Bloomberg said.

Some argue that the mayor simply failed to clarify what Executive Order 34 was supposed to do, since similar policies have been successfully implemented with support from immigrants in other cities.

Designed to comply with the 1996 federal law, the language of Order 34 was vague enough that a literal reading of the order would allow police to make "sweeps of immigrants who are not suspected of any crime," attorney Scott Rosenberg told the Village Voice.

Until Order 34, every mayor since Ed Koch had followed a "don't tell" policy and didn't cooperate with the federal immigration agency. In 1996, Congress passed a law that said the city cannot forbid city workers from voluntarily reporting illegal aliens. Mayor Rudy Giuliani resisted but lost when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the federal law and ruled in 1999 that Koch's policy was illegal.

Though similar to Koch's order, city officials said, Order 41 does not violate federal law since it follows guidelines from the 1999 ruling by making confidential a larger class of information -- for example income tax records, sexual orientation, status as a victim of domestic violence -- not just immigration status.

Critics added that the mayor's change of heart comes at a time when he needs immigrant support, especially from the Hispanic community, to help boost his sinking job approval rating.

"Given the general erosion of his position in the opinion polls, Bloomberg really needs to have a strategy for rebuilding support in these constituencies," John Mollenkopf of the Center of Urban Research told the New York Times.

However, others are pleased with the new initiative and don't think that it matters whether the mayor has a political agenda. "What is really important is not the mayor's reasons … but the end result of his decision to amend the order," wrote columnist Albor Ruiz in the Daily News. "Bloomberg actually made [Executive Order 41] the strongest local confidentiality policy in the nation."

But as Bloomberg took steps to protect New York City's illegal alien population, Congress was taking another to toughen federal immigration law. This past July, Representative Charles Norwood of Georgia introduced the Clear Law Enforcement for Criminal Alien Removal (CLEAR) Act, which would allow local police to enforce federal civil immigration law. At the moment, local police can only enforce criminal immigration law. No one is quite sure how the CLEAR Act would affect Bloomberg's executive order.

An immigrant from Bangkok, Thailand, Chaleampon Ritthichai is the editor of The Citizen.

New York City Council STATED MEETING - September 30, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - September 30, 2003

Quote of the Day:

"Does anyone know the score?" - City Council Speaker Gifford Miller inquiring about the afternoon playoff game between the New York Yankees and the Minnesota Twins. The meeting was brief so that the speaker could attend the game.

Meeting Summary:

The New York City Council marked the beginning of the Major League Baseball playoffs and the first game of the American League Division Series for the New York Yankees by passing a bill (Intro 482-A) that makes trespassing on the playing field of a professional sporting event a "Class A" misdemeanor.

The legislation stems from a series of incidents in which fans have run onto the field and assaulted coaches and umpires in Chicago. It only applies to professional sporting events, and college, high school, and recreational sports are exempt from the law. Those who violate the law could receive up to a year in prison and up to $1,000 in fines.

"This legislation protects not only participants on the field, but also those watching a sporting event, from lawlessness and disorder," said Speaker Gifford Miller. The bill passed by a vote of 42 to 1 (8 members were absent), with only Brooklyn Councilmember Charles Barron voting against it.

The council also unanimously passed a bill (Intro 195-A) to create a 15-member advisory board for the Taxi and Limousine Commission, consisting of drivers, members of the public, owners, organizations advocating for drivers, and agencies enforcing commission rules. The mayor and the council speaker will appoint the members and supporters hope that the board will be a constructive way to address taxi issues in the city.

"This is something that will bring a voice to many drivers who don't have a voice... and it improves the safety of the industry," said Washington Heights Councilmember Miguel Martinez, who once worked as a cab driver.

The City Council also passed a measure renaming 77 streets in the city, most for police officers and firefighters who died on September 11, 2001. Streets were also named for New Yorkers who died in combat in Iraq and for Celia Cruz, the salsa star.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for October 15.

For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.

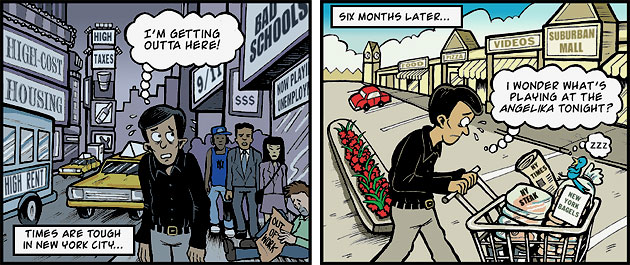

Leaving New York

![]()

Why New Yorkers Are Leaving: The City Is Too Expensive by E.J. McMahon City Schools and Housing Are Inadequate by David Kallick New Yorkers Who Left: Rondrae Hunter A Frustrating Apartment Search Allison Woods Struggling with Strollers and Schools David Bassine Fear of Terrorism Stefan Kochi Bad for Business |

He had not planned to do this. But, after suffering through a season of tax increases, a subway fare hike, a stagnant economy and sundry other outrages, "what finally took me over the edge," he said, "was the act of going out and looking for an apartment." The best place he could find within his price range was on Fresh Pond Road in Queens. The floor slanted, and although the apartment had as a selling point the fact that it was close to the subway station, it turned out to be too close; he was afraid the noise would keep his baby awake.

To the Hunters, then, a main reason for leaving New York was the lack of affordable housing. For Allison Woods, another native New Yorker, it was the school system. Stefan Kochi, a businessman originally from Albania, blames the economy. David Bassine convinced his wife and two sons to leave because, he says, "I got scared after 9/11."

There is no question that individual New Yorkers are leaving the city. What is unclear is whether their exodus is anything unusual or alarming. It certainly seemed that way from a recent spate of articles and reports based on newly released data from the United States Census Bureau. For example, according to an analysis of this data for a report by the Center for an Urban Future on the economic challenges facing the city, some 150,000 Americans moved out of the five boroughs of New York City in the year after September 11th, 2001 - a 15 percent rise from the year before and 28 percent more than 1999.

But a closer look at these statistics reveals that, for some reason, the census bureau was counting only Americans, and not including any statistics about foreigners. Yet New York is now, and long has been, a magnet for immigration, and the influx of immigrants is likely to have more than made up for the outflow of residents. Indeed, there is some evidence that the population of the city is actually at an all-time high.

"People have always left New York in large numbers, and people have always arrived in New York in large numbers to replace them," said David Kallick, of the Fiscal Policy Institute. "I don't see anything significantly different about what's happening now."

Others believe, though, that the departure of long-time New Yorkers is both a problem in itself and a symptom of a city in trouble. Advocates and analysts have seized upon individual stories of fleeing New Yorkers to add new fuel to their ideological fires. On one side are those who say more government action - to build affordable housing, to improve the schools and to develop the economy - is needed to keep people here. (See essay by David Kallick.) On the other are those who argue that, in effect, less government action - especially lower taxes - will bring down the cost of living and keep the middle class within the five boroughs. (See essay by E.J. McMahon .)

GAINS AND LOSSES

For much of its history, the story of New York was one of ever-increasing population. This changed after World War II with the rise of the suburbs. The 1970s, when the fiscal crisis and a crime wave caused many people to lose faith in the city, saw the sharpest population decline in the city's history. That decade ended with 824,000 fewer New Yorkers than when it started. After relatively small gains in the 1980s, the population went through a period of sharp expansion during the 1990s boom, increasing by 685,000 between 1990 and 2000 to a record 8,008,278.

Even as the population grew, says Joseph Salvo, director of the Population Division of the New York City Department of City Planning, the city lost individuals to other parts of the region and elsewhere in the United States. But, unlike the situation in many other cities, these people were replaced by newcomers (largely foreign immigrants) and by newborns.

That continues, says Salvo, who says there is no evidence of an increase in people leaving the city. "In fact," he says, "we have evidence to the contrary" including a rise in the number of permits for new housing issued by the city in the past few years.

But the Center for an Urban Future disagrees. Jonathan Bowles, co-author of its recent report, has concluded that, since September 11th, 2001 in particular, people have been leaving in increasing numbers again and fewer newcomers are coming to replace them. Although that trend may be short-lived, Bowles said, "there's certainly a more negative attitude toward New York these days...The combination of service cuts, the economic crisis, the fiscal crisis, 9/11. It just doesn't seem as optimistic a place as it was a few years ago."

Bowles thinks there is reason to be concerned about the long run. As he writes in the report, if New York "retains only a short-run, narrowly based appeal for young people, who then leave later in life, it may find itself without a stable base of workers and entrepreneurs."

E.J. McMahon of the Manhattan Institute believes that the overall statistics, whether there has been a net loss or a net gain of population, are not as much the issue as the specifics of who is moving in and who is moving out. "The people who leave tend to have higher incomes than those who move in," he said. While McMahon does believe that the "vitality and dynamism of immigrants are very important to the city," he said that such immigrants usually demand more in the way of social services than those who move out. Their education, he said, also tends to be more expensive.

REASONS FOR LEAVING

9/11

David Bassine was one long-time New Yorker whose attitudes changed after the terror attacks. He moved to Connecticut in July 2002 after 12 years in the city. "With two kids, I just didn't want to be there. We were in the middle of the anthrax scare, and I was opening my mail with gloves and a mask on. I was nervous about taking my kids on the subway, and I just got frightened about the whole thing. I didn't want to put my children at risk."

Housing And The Schools

But in examining the reasons people left after September 11, most policy analysts describe the terrorist attack as a shock that simply exposed the city's existing problems. Bassine himself talks of the high cost of housing, and of the fact that his two sons were approaching the end of their elementary school years. They had attended a neighborhood public school that he and his wife were very happy with, but they worried about finding a nearby middle school of similar quality. School was also looming for Allison Woods when she moved from New York, pregnant with her second child. Woods, knowing that she could not afford New York private school tuition for two children and lacking faith in the public school system, moved to High Falls in upstate New York. There, she said, "we could use the public schools, or private schools that cost half...what they do in the city."

The Economy

Economically, New York had started to cool off even before the World Trade Center attacks. City Comptroller William Thompson released a report (in pdf format) last month stating that the city has been in recession for 10 consecutive quarters, dating back to the beginning of 2001.

Stefan Kochi, an Albanian immigrant living in Boston, moved to New York just in time to feel the effects of the economic slump. After opening a New York office for a Boston-based company that built websites for start-up firms in 1999, Kochi was forced to close the New York office in the summer of 2001. He planned to stay in the city but business associates changed his mind.

"Everybody was lukewarm about the economy in general," he said. "I thought if these people who I had planned to rely on...were not comfortable, the recession must be pretty bad."

Reluctantly, Kochi moved back to Boston, where he started a new company, which will now hire Bostonians of course instead of New Yorkers.

While the economy in much of the rest of the country shows some signs of recovery, New York's remains slow. Production gains have stayed below national levels, and the city continues to lose a larger percentage of its jobs than the country as a whole. In the second quarter of this year the city lost 10,600 jobs. Since January, 2001, the city has lost 241,500 jobs.

KEEPING PEOPLE HERE

Almost everyone agrees that the city's problems in housing, schools and the economy spur people to leave. What they disagree over is how to solve these problems.

Conservative policy analysts think high taxes worsen the economic situation. Most people do not specifically cite higher taxes as the reason for leaving, McMahon concedes, but the taxes create the conditions they do name, such as a lack of jobs and affordable housing. "There's no way to underestimate what the tax burden does to the cost of living here," he said. The solution, he believes, is cutting taxes and then making government more productive. He also calls for doing away with rent control, which he sees as a major barrier to the building of new housing in the city.

But those on the other side of the political spectrum see a need to maintain services and take a more active role in economic development. Bowles believes that recent hikes in the property and city income taxes were a reasonable way for the city to deal with its economic problems. "I think if the city was going to be drastically cutting funds for police or education, or other basic services, it probably would have made things even worse than they are right now," he said

The city's plan for economic development has suffered because of tunnel vision, focusing only on a few sectors, namely finance, insurance, and real estate, according to Bowles. He writes in the center's report that "the city should adopt a broader economic strategy to facilitate the creation of a better climate for growing small businesses, tap the potential of the boroughs outside Manhattan and put New York's human assets to better use."

New York is in a better position to do this now than in the past, largely because of gains through the 1990s that make more of New York a better place for people to live and businesses to develop. While housing and schooling remain problems that convince people to leave, said David Kallick of the Fiscal Policy Institute, "there have been periods when crime and safety and 'quality of life' issues were also big problems."

The declining crime rate and the virtual elimination of the most obvious quality of life violations (such as graffiti), as well as the overall development of many neighborhoods in the outer boroughs, have enabled many to stay in the city who might otherwise have left. So while almost twice as many people left Manhattan from July 2001 to July 2002 as did in 1999, many fled not to New Jersey or Long Island but to Brooklyn or Queens. They are no longer Manhattanites, but they remain New Yorkers.

To some extent, the ebbing and flowing of the city population is inevitable. "People come to the city looking for opportunity," said Salvo. When they achieve what they came here for, he said, they then leave to buy homes, pursue other opportunities or to retire - and are replaced by new people looking for opportunity. "It makes New York one of the most interesting places on earth." The key thing, said Salvo, is that those who leave are replaced.

For now, he maintains, that is still the case. Despite the bad schools, expensive apartments and high taxes, New York still exerts an irresistible draw. "I started to love this city from the first moment," said Jennifer Chert, a 23-year old Italian who spent several months living in New York earlier this year. In an effort to stay longer, Chert worked cleaning dog cages at a pet shop in Queens. "Obviously it was not a great job," she said. "But to stay I think I would have cleaned all the windows in the Empire State Building."

Meanwhile, after three months, Ron Hunter, while not exactly having second thoughts, is not entirely exulting in his new home. "Maryland is different, and I am having issues trying to get used to it. The slower pace of everything is hard to adjust to. Compared to New York, anything is slow, but this is really slow."

Low Voter Turnout

The primary elections for city offices held September 9, 2003, were barely noticed by most New Yorkers. Significant only in the lack of attention they garnered, the primaries were one of the lowest turnout elections in recent memory. Although there were a couple of close races, in the end, no incumbents were defeated.

Although low turnout is considered by many to be an example of what is wrong with the voting process, it doesn't always have to be a sign of foreboding. Sometimes low turnout is an indication that the electorate is basically pleased with the ways things are, and doesn't feel an overwhelming need to make major changes.

And history would back up that theory. Heavy voter turnout tends to produce change: getting rid of an incumbent or putting a different party into power or changing the entire make-up of a legislative body. Conversely, low voter turnout can be expected to send incumbents back for another term, or reward prohibitive front-runners, or shore up the dominant political party structure.

Not always, of course. But usually.

So low turnout can be a sign that voters are satisfied, or at least not extremely disgruntled. But low turnout can also be an indication of an electorate that feels disconnected from the political process. If voters feel their vote isn't going to matter, or isn't going to count, or isn't going to be counted, this will understandably turn them off the idea of making the effort to get to the polls. And if they feel there is no difference between the various candidates running, and no real choices available to them, and no potential for change pending the outcome of the election, they will be further alienated from the process.

Whatever the reason for low voter turnout, it is far from the ideal. The basis for the efficacy and legitimacy of a representative democracy is the concept of consensus: of everyone's opinions and choices having been equally weighed and the majority, or at least the plurality, emerging.

In party primaries, there is a marked correlation between the increasingly low turnout and the declining influence of political parties themselves. It would be difficult to mark the causal connection: whether the low turnout led to the lessened influence of political parties, or the reverse, the weakened party structure is the reason for the lower turnout.

In either case, political party primaries have always been an insider's game: so-called "family business." The party faithful, those few who are heavily involved in party organization and activities, are the ones who consistently turn out and vote. The up side is that decisions about who will represent the party on the general election ballot are made by those who are well-informed about who is running, who are aware of what those candidates represent, and who are actively seeking an advocate for their concerns.

The down side is that this tends to produce two major candidates (if that; in many districts only one party manages to field a candidate at all) who are the respective choices of a tiny percentage of the voting age population, at either end of the political spectrum.

And the low turnout in this year's primary is especially significant as New Yorkers prepare to vote on a ballot question in November. In the matter of city elections, should the party primary system be abolished, and replaced with a non-partisan election? If the law was changed, and New York did go to a non-partisan election, the party primary would be replaced by an open election, and any registered voter would be eligible to vote for his or her choice, regardless of party enrollment or affiliation. The top two vote getters would then move on to the run-off, which would replace the general election.

Advocates of the proposed system argue that ending party primaries will increase voter turnout. And this is one possibility. It is also significant to note, however, that in an adversarial system, candidates tend to focus on persuading active voters, not engaging new ones. Most campaigns are not interested in increasing voter turnout overall, only in turning out their own known supporters.

And in a general election, the work of Get Out the Vote, or GOTV, has historically been a function of the party. It would be difficult to predict who would take on the expensive and exhausting task of coaxing and transporting millions of people to the polls on election day once the party system was no longer in effect.

Turnout on election day can be affected by any number of factors: the weather, traffic patterns, the overall political climate. And it is also significant that this year's party primary and the November general election are an exception to the regular election schedule. New York City had the same round of elections just two years ago, but instead of serving the normal four-year terms, city officials were elected to two-year terms in order to incorporate the latest census data.

But whatever factors may affect turnout, it remains, for now, largely predictable. Voting, while a choice, is also a behavior. Like many behaviors, it is not only purposeful, but habitual. And changing a habit, good or bad, is never easy.

Susan Reefer is a Republican pollster and media strategist. She is based in New York City.

Turning Teens Into Techies And Online Activists

There is a bill in Congress to prohibit the use of the word "French" by U.S. citizens - French fries would have to become freedom fries; French toast, freedom toast; French Canadians, Freedom Canadians. This at least is the claim of a satirical Web site linked to by Patriots On Parade, one of several Web sites put together by New York City high school students as part of the sixth annual Digital Day Camp, the brainchild of a non-profit organization that focuses on new media education, Eyebeam.

Each year, Digital Day Camp picks a theme; this year, it was civil disobedience. In particular, the program focused on alternative methods of disagreement and protest among many communities. This year's projects included a spoof on homeland security, Homelandschmecurity, which features a satirical cast of fictional super heroes like "Duct Tape Man," "Gas Mask Man," "Detention Center Man" and " Shoe Inspection Man"; Classism Stinks, which includes man-in-the-street interviews about sanitation issues, and photographs of garbage, with the goal of highlighting the difference in garbage problems between rich and poor neighborhoods; and Sweatcampwhich uses a comic approach to probe child labor and sweatshops.

At a time when the music industry is filing lawsuits against 12-year-olds for downloading songs from the Internet, it is refreshing to learn of an organization that channels teen online savvy into activism and political engagement.

Another form of engagement by a New York non-profit is the mighty MOUSE, which teaches technology skills to public school kids. Since 1997, MOUSE -- "Making Opportunities for Upgrading Schools and Education" - has created "MOUSE Squads," as they are known, in some three dozen New York City public high schools and middles schools, recruiting and training students to set up and run a technology "help desk" in their schools. The help desks provide tech support for about 22 hours a week.

Almost a third of Squad members are girls and almost three quarters of MOUSE Squad students are Latino, Asian and African American. MOUSE is particularly interested in promoting young women's interest in technology. In addition to the MOUSE Squads, there are 1,500 volunteer tech professionals who have worked a collective 40,000 hours to put 50,000 teachers and students online in the past year.

Some of MOUSE's recent projects include building a community technology center in Washington Heights and installing computers and a technical training program in 14 schools in Central Harlem. The organization also ran a city-wide online newspaper contest for teams of high school students, in partnership with Bell Atlantic, The NY Times, iXL and Small World Entertainment.

MOUSE has also helped the city save over $400,000 for 36. "In these difficult economic times," said Councilmember Gale Brewer, a champion of the program, " MOUSE Squads not only save the city money that it would otherwise have to spend on outside technical support, but the program also teaches critical jobs skills that are absolutely essential in this new economy."

There are many other worthy tech programs for youth:

Computers for Youth is an organization that aims to improve the educational, social and economic prospects for low-income students and their families by providing them with home computers and the skills to use them.

Change for Kids is a non-profit organization dedicated to improving children's education in New York City's most under-funded public schools.

Voluntech aims to promote the equitable distribution of technology by bringing together volunteer technology experts with non-profit organizations, schools, and community groups.

City Kids aims to engage and develop diverse young people to effect positive change in their lives, their communities, and the world. Their programs include CyberLinks which exposes youth to emerging computer technology.

Persholas provides career skills and rigorous on-site training for future computer technicians.

Laura Forlano is a doctoral student studying communication technology policy at Columbia University.

New York City Council STATED MEETING - September 17, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - September 17, 2003

Meeting Summary:

The members of the New York City Council spent much of the summer campaigning for reelection - not drafting new legislation - and so the council had a simple agenda for its September 17 meeting.

The council only passed one new bill (Intro 555) approving a new taxi station in Queens for a company called "A Ride For All." The new car service will be the first to exclusively provide vehicles that accomodate passengers who use wheelchairs or scooters. The company will begin with only five vehicles, but if demand is high enough it could quickly expand to 50 cabs or more, according to Councilmember John Liu who chairs the transportation committee.

The council approved the station by a vote of 48 to 0, but Lower East Side Councilmember Margarita Lopez warned that it should not be seen as a sign that the Bloomberg administration was meeting the transportation needs of disabled New Yorkers.

"The administration has been sitting on a mandate to provide bay stations with [handicap] accessible cars," said Lopez. "This piece of legislation is good, but it is a decoy."

The council also approved five new appointments to city commissions. Under the city charter, the mayor and the council must agree on certain appointments and these are routinely done with little debate.

However, the appointment of Rudy Washington, a former deputy mayor in the Giuliani administration, to the New York City Civil Service Commission drew criticism from some council members. In 1994, Mayor Giuliani dismantled a program that steered government contracts to minority owned businesses and Washington, as the commissioner of the Department of Business Services, oversaw the policy changes. Washington also sparked controversy when he shut down street vendors on 125th Street in Harlem and Fulton Street in Brooklyn.

"His record was horrendous," said Councilmember Charles Barron. "I think when we appoint people to positions as important as dealing with labor and workers, we need people who are more friendly to workers and create jobs."

Other members - including Dennis Gallagher and Helen Sears - spoke highly of Washington. "I have never known him to perform his work as a Republican or a Democrat," said Sears. "He has performed his duties as a public servant."

Washington's appointment was approved by a vote of 46 to 2; Charles Barron and Bill Perkins voted "no."

Alice Olick and Aladar Gyimesi were also appointed to the New York City Tax Commission, and Belle Horwitz and Robert Carver were named to the Environmental Control Board.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for September 30.

For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.

Put Class Size on the Ballot

|

When school opened on September 8, class size in some elementary schools had increased 30 percent from last year's average of 25 students, Newsday reported. A number of middle schools have classes of 37 students compared to 32 in the 2002-2003 school year, and high schools are contending with nearly 1,000 more students than they had last year. In one high school in Queens, the Post found, 300 classes exceed union limits of 34 students per class, while another school in Manhattan has run out of space entirely, forcing 100 students to sit in the auditorium instead of classrooms. According to the UFT, more than 9,000 classes now violate union contractual limits on size. About the only grade level where classes have not increased in size is pre-kindergarten, since state law strictly limits those classes to 18 children per teacher.

Study after study has shown that smaller classes lead to higher grades and test scores, particularly for poor and minority students, as well as more parental involvement, fewer disciplinary problems and lower dropout rates. In their recent ruling that the state school aid formula for New York City illegally deprives city students of a sound basic education (in pdf format), judges on the state's highest court cited the city's oversized classes as key evidence that the state was providing our children with an inadequate education.

Overcrowding in city schools has endured for decades and through many administrations. Though Mayor Michael Bloomberg has acknowledged the importance of class size and promised to speed school construction and expansion, he has reduced the capital budget for schools by over $3 billion, a cut of 53 percent, according to the Independent Budget Office (in pdf format). And Chancellor Joel Klein has apparently forgotten his pledge not to allow other class sizes to increase.

Whether this fall's deterioration is due to poor management, misplaced priorities, budget cuts, a misguided interpretation of the federal No Child Left Behind law, or because students are being forced out of some larger high schools that are being broken up into new smaller high schools, it is clearer than ever before that we must address this critical problem.

Recently, a coalition was created called New Yorkers for Smaller Classes. It is composed of advocacy organizations, unions, and parent groups. On August 18, the coalition presented the city clerk with petitions signed by more than 115,000 registered voters who support the creation of a new City Charter Revision Commission that would consider limiting class size in all grades. This is more than twice the number of signatures needed to put this question on the ballot in November.

Once the charter commission is up and running, it would decide whether a proposition to limit class sizes should be put before the voters in November 2004. Members of the commission would have many other important issues to debate and consider, including what specific class sizes might be proposed and how smaller classes could be funded. Clearly it will be costly to build classrooms and to hire the additional teachers needed for smaller classes. But it would be worth it.

As Assemblymember Steve Sanders pointed out when we presented our signed petitions to the city clerk, because of the state court's decision that our schools provide an inadequate education, billions of dollars in additional state education aid are expected to flow to New York City. Moreover, economists estimate that the benefits of smaller classes are twice as great as the costs, in terms of the future earnings of high school graduates alone. Oversize classes damage the city's competitiveness, by hurting our ability to provide an educated work force. They also spur families to move to the suburbs when they have children. A recent report from the Center for an Urban Future (in pdf format) points out that the most profitable economic development the city could embark upon would be to invest in improving basic services like education, in order to "build [our] middle class and keep people in the city."

Pre-school and reducing class size are the only educational reforms that have been proven to substantially reduce the achievement gap between rich and poor, and between white and minority students. We need a city charter commission to come up with a realistic plan to limit class size for the sake of our children as well as the economic future of this city. Then, let the voters decide.

Leonie Haimson is a parent, education advocate, amd chair of Class Size Matters, an organization dedicated to achieving smaller classes in NYC public schools and a member of the New Yorkers for Smaller Classes coalition.

Related Article

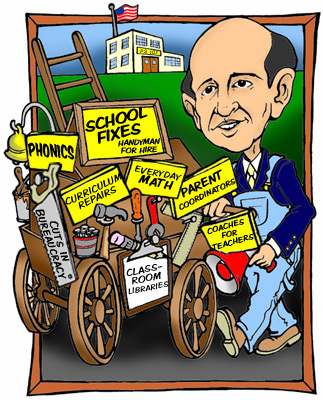

School Reforms of 2003

School opened last week with a new bureaucracy, 1,200 new "parent coordinators," teaching coaches and a new standard curriculum. Will any of this fix the system?