City Council Stated Meeting - July 27, 2005

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Gotham Gazette covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

QUOTES OF THE DAY:

"There will no longer be a tax on worship." - Councilmember Hiram Monserrate on suspending parking meters on Sundays.

"New Yorkers who pray on Saturdays and Fridays have been left completely out of the considerations of this bill." - Councilmember John Liu in response.

MEETING SUMMARY:

PARKING METERS ON SUNDAY

Since the city instituted Sunday parking meters three years ago, many churchgoers have complained about having to feed meters while they are in church. Some pastors have even complained to local politicians that their congregants must choose between walking out to the street with a handful of quarters in the middle of a sermon or getting a parking ticket.

To put an end to what some have dubbed "pay to pray," the New York City Council passed a bill (Intro 669) that would eliminate the need to feed parking meters on Sundays.

"This will impact hundreds of thousands of people who choose Sunday as their day of worship," said Councilmember Hiram Monserrate, who drafted the bill. "There will no longer be a tax on worship."

The council says it is also a way to give something back to New Yorkers who have seen tax and fee increases in recent years. And they hope it will help stimulate shopping.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has promised to veto the bill, arguing that the city would lose needed revenue. Sunday meter parking generates $12 million a year and was instituted in 2002 during the post 9/11 budget crunch.

Bloomberg also argues it will create additional parking problems because people will hog the parking spaces, parking their cars on Saturday night and not moving them until Monday morning.

The bill passed by a vote of 41 to 3 (seven members were absent). John Liu, Tony Avella, and Helen Sears - who all represent districts in Queens - voted "no" on the measure.

"I think it will make those parking spots much harder to find," said Councilmember John Liu, who chairs the council’s transportation committee. and also argued that the action may lead to an increase in double parking and make streets more dangerous for pedestrians.

"New Yorkers who pray on Saturdays and Fridays have been left completely out of the considerations of this bill," added Liu.

The council has more than the 34 votes needed to override the mayor and has promised to do so.

"This vote will tell the mayor three things," said Councilmember Vincent Gentile, who also helped draft the legislation. "Enough is enough. Leave us alone on Sundays. And sign this bill into law."

TAX BENEFITS FOR LEAD PAINT ABATEMENT

In February 2004, the New York City Council passed a law which requires owners to apartments built before 1960 to remove lead paint and dust and to give an annual account of children under the age of seven living in the building. Critics have charged that the regulations make it more expensive to renovate affordable housing.

In an effort to help landlords cover the cost of lead paint removal, the city offers tax benefits. And the council passed a measure (Intro 607-A) which extends these tax benefits to more building owners.

In the past, landlords had to prove there was a child under the age of seven in the building in order to receive the tax break. Under the new legislation, any landlord can apply.

It also reduces some fees, liability, and regulations that have discouraged some landlords from doing abatements. The council hopes that the measure will prevent landlords from passing the cost of removing lead paint on to their tenants.

"This will prevent further lead poisoning of our children and preserves affordable housing," said Councilmember Miguel Martinez.

SENIOR CITIZEN RENT INCREASE EXEMPTIONS

The council also passed a measure aimed at providing rent relief for low-income senior citizens.

In order to qualify for the senior citizen rent increase exemptions (also known as SCRIE), an applicant must be over the age of 62, have an annual income of $24,000 or less, and pay one-third or more of their income in rent.

The council's bill (Intro 666) will increase the maximum annual income requirement from $24,000 to $29,000 (in $1,000 increments each year) over the next five years.

In return for the exemptions, the government pays property owners an amount equal to the lost rent. The council estimates that the legislation will cost about $13.8 million over the next five years.

DISABLITY RENT INCREASE EXEMPTIONS

In June, the New York State Assembly passed legislation to create a similar rent exemption program for people with disabilities. The council passed legislation (Intro 667) to enact the program in New York City.

The disability rent increase exemption (or DRIE) will help 20,000 disabled New Yorkers, who earn less than $17,004 a year, and who pay more than 30 percent of their income in rent.

Although advocates for the disabled and council members hailed the new program, they said the salary requirements are too low and should be equal to the limits set for senior citizens.

SUMMER RECESS

Each year, the City Council takes a summer recess. There are generally no committee hearings during the months of July and August, though the council does meet once a month to pass urgent land-use measures or other legislation.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for August 17, 2005. The council resumes its regular schedule of hearings and meetings in September.

Â

The Race for Public Advocate

|

The Race for Public Advocate has moved to a new location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

311's Growing Pains

There is a playground on the Lower East Side that, theoretically at least, is open to the public during daylight hours. But when Susan Stetzer, who lives next door, would walk by, she often found its gates locked.

Each time she noticed, Stetzer took out her cell phone and called 311. A record was made of the problem, and sometimes the gates were opened. But sometimes they weren't. Eventually Stetzer used her role as the district manager of the local community board to find a permanent solution. When she did, her months of 311 calls helped establish evidence of a persistent problem - even if those calls didn't manage to solve the problem themselves. Stetzer and the community board recently reached an agreement with the parks department that will keep the playground's gates open during the day.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg established the 311 call center as a single hotline for non-emergency calls to the city in 2003, so that New Yorkers could more easily voice their concerns. Its first two years in operation have convinced many people of its potential - the number of calls to 311 has more than tripled, so that it now receives about the same number as 911. But two years is also time enough to reveal the system's shortcomings.

Some have noticed that the speed of service has slowed. "It was getting better and better and better, and then all of a sudden it got worse," said Stetzer, who grew accustomed to calling to report illegal sidewalk cafes and other problems she came across. Tired of the increasingly lengthy hold times, she recently assigned a member of her staff to call 311 for her.

Other concerns revolve around how the system is used in the context of city government as a whole. Stetzer and other managers and members of community boards across the city - who see handling constituent complaints as one of their primary functions - criticize the Bloomberg administration for not sufficiently integrating the community boards into its new system. Others have become impatient with the pace of expanding it as a management tool for city government.

So, after setting in motion a serious shift in the workings of city government, the Bloomberg administration is now being challenged to follow through.

"They're using technology to force changes in the way government works on some level," said Bruce Lai, a staff member for the City Council's committee on technology. "It's a long process - New York City government is massive."

A POPULAR SYSTEM

When New York launched 311 in March 2003 it was not a new idea. In the late 1990s the Clinton administration conceived it as a way to lessen the burden on 911, and Baltimore and Chicago put the system in place years ago. But New York's system surpasses its predecessors in both scale and complexity.

The sizeable project, many say, seemed a logical undertaking for a businessman mayor who had run a media business that took some pains to provide clients with individualized attention."His City Hall equivalent to that sort of pampering is the new 311 telephone hotline," wrote Christopher Swope of Governing Magazine in August 2004.

It has arguably been the mayor's most sweeping change to city government. It has changed the way that the city takes complaints by:

- Consolidating almost 40 call centers from 17 different city agencies into a streamlined, centralized operation

- Giving callers tracking numbers for complaints

- Allowing residents to call in non-emergency complaints 24 hours a day

- Fielding calls in 171 languages, by employing English and Spanish speaking operators, and hiring a translation service for other languages

These services have won over New Yorkers like Joey Arak, who first called 311 in the middle of one night last summer after a car alarm began blaring outside his Orchard Street apartment. The call resulted in the arrival of several police officers, who broke into the car, turned the alarm off, re-locked the car, and drove off.

Arak has only called 311 a few times since then, but his experience has turned him into something of a 311 zealot.

"Last week I was walking to work after grabbing lunch, and a teenage girl came up to me and said that the cashier in a nearby bodega stole her money and wouldn't give it back or something, and if I had seen any policemen pass by. My reply? 311. Whenever anyone has a parking question, my reply? 311." A 311 operator said that in fact it would probably be more appropriate to call 911 in the case of theft; 311 is clearly the better choice for parking advice.

|

The numbers show that the city as a whole has taken to the system. In March 2003, about 310,000 people called 311; in May 2005, it fielded over one million calls. Still, there has been no major change in the number of annual calls to the 911 emergency system, which has remained steady at about 12 million a year.

Many people call 311 to complain - over the first two years, heat and hot water complaints and noise complaints were far and away the most common calls. But the city has found the system useful for other campaigns as well. About 96,000 people called 311 in May to request free nicotine patches, and 110,000 people called on September 30, 2004, largely to find out when they would get their $400 property tax rebate.

The system has also served as an aide to agencies and public officials. Even the public advocate's office, which runs an ombudsman line that would seem to be in direct competition with 311, has found its job made easier by the new hotline.

"Our call volume has actually gone up, because 311 transfers calls to us," said Anat Jacobson, a spokesperson for Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum. "It's been a really useful tool."

For Paul Lee, however, the experience has been more mixed. Lee calls regularly, "sometimes with great success and sometimes with abject failure." (He also posts neighborhood problems to Gotham Gazette's Fix-its.) streetlights or traffic signals go out, the problems are usually fixed quickly, said Lee, a community activist in Manhattan's Chinatown.

But he found that 311 was stumped on how to deal with a depression on Pell Street that had grown large enough that "cars [were] sinking into the thing." The city was unable to fix the problem for well over a year, and operators seemed confused and irritated when Lee described the problem interchangeably as a pothole and a sinkhole. The problem persisted until Lee saw a member of a Department of Transportation road crew on the street and asked for advice.

"He said 'Call it an undermine. When you say the word undermine, they know what you mean and we'll be right out.'" Lee did, and the problem was fixed within two weeks.

"When you get into a zone that has no clear delineation," said Lee, "then it gets a little weird."

KEEPING UP WITH COMPLAINTS

Since the city launched 311 it has both increased the number of operators it employs and increased the system's budget. [The Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications did not provide exact statistics by press time].

Still, the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, is having some trouble keeping pace with its growing popularity. Between May 2004 and May 2005 - a period during which call volumes rose 46 percent - the average time a caller spent on hold went from 18 to 30 seconds, and the percentage of calls answered within 30 seconds dropped from 79 to 71 percent. Gino Menchini, the agency's commissioner acknowledges that this is "something that has to be managed," but also noted that the system is still meeting its goal of answering calls in an average of 30 seconds.

"We provide service levels that exceed and are better than what you could get at most banks or other types of customer service institutions," he said. "It's not surprising that as our call volume went up significantly that we had modest increases on hold times."

Making it easy to complain, of course, can lead to uncomfortable situations for those being complained about. Bloomberg discovered this immediately when 7,500 people called to complain about the mayor himself in the first three months the system existed, as reported in the New York Post. One caller accused the mayor of "putting people's lives in danger" by closing firehouses, another called him a "fool" for stating that the smoking ban would save 1,000 lives a year. (The mayor's office said this proved that people liked calling 311; besides, a spokesperson added, the calls made up only about 0.004 percent of the system's total volume.)

More seriously, the police department also saw a spike in the number of complaints to its Civilian Complaint Review Board despite what many say is a time of relatively low tension between police and civilians, a disconnect that the department explained by noting how easy 311 is to use.

Some restaurant and bar owners, meanwhile, say that the simultaneous implementation of the 311 system and another signature policy of the Bloomberg administration - the smoking ban - has been a "double whammy." The smoking ban, said Robert Bookman of the New York Nightlife Association, has pushed customers into the street, increasing tension with nearby residents. Even in times when no noise ordinance was actually being broken, he claimed, peeved neighbors found they could lash out at bars by anonymously calling 311 and making any kind of complaint, such as a report of a non-existent fight.

"We have considerable anecdotal evidence that people are using the system to complain that they don't like the bar down the block or the nightclub across the street," said Bookman. "It's causing unneeded inspections that disrupt the business and can sometimes kill the flow of the evening."

Some members of the City Council believe that these false complaints waste considerable city resources, and have proposed legislation that would require the 311 system to be able to trace callers much like the way 911 does (Intro 399); (Intro 509). Menchini questions the scope of the problem, and says asking 311 to keep track of callers will cause longer hold times without actually discouraging false complaints.

|

MORE THAN JUST COMPLAINTS

While about four of every ten calls placed to 311 are immediately transferred to the correct agency, the system has always been envisioned as more than a citywide switchboard. Those who run 311 - and those who think they could run it better - are looking at other ways to use the system.

The 311 system has integrated the buildings department's schedule into its database, and 311 operators can now arrange for visits by city building inspectors. The Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications is now working with the New York City Housing Authority to do the same thing.

Others say that 311's real potential lies in the immense amount of data it has accumulated.

There has already been a move to take advantage of this. The police department recently announced that it was establishing a "Real Time Crime Center", which allows detectives to tap into the 311 database, along with several other information sources, to get timely data for investigations.

But critics say that the city has not done nearly enough.

"311 has been a way of directing phone calls better. It has not been used as a real management tool," said City Council Gifford Miller at a recent debate between the Democratic mayoral candidates. "What doesn't happen is the next step, which is to say, "Okay, we've received 20,000 phone calls. Where are those phone calls coming from, how can we now better direct our resources?'" The public advocate's office and community boards have made similar statements, saying that the data in the 311 system should be used more extensively in the budget process.

Menchini says that such data analysis has always been a part of the plan, and that critics should realize that the two-year old system is still developing.

"If you tried to do everything at once," he said, "you'd get nothing done."

311 AND COMMUNITY BOARDS

Even if it is easier to complain about inattentive landlords, pothole-ridden streets, or noisy bars, the real question is whether these problems are actually getting fixed.

"At the end, when the agency doesn't do anything for you, all 311 has done is gotten you to a dead end," said Jacobson of the public advocate's office.

Jacobson notes that there are other avenues for people who need the city's help, and 311 has not eliminated the need for them. While the system can resolve simple issues, she said, complicated problems often need the more extensive follow-up of a public advocate's office or a community board, as was the case with Stetzer's playground on the Lower East Side.

The city's 59 community boards have seen 311 as a mixed blessing. Craig Hammerman of Brooklyn's Community Board Six says that 311 has freed up his resources by giving his constituents an effective way to handle most minor complaints.

"No citizen should have to call a community board to get a pothole fixed," he said.

But Hammerman and others also see major problems that 311 needs to address. In a survey of community board district managers taken last fall by the public advocate's office, 80 percent of respondents said the system needed to be improved (in pdf format). A large majority said 311 call takers lacked knowledge of city agencies, that the system failed to solve problems in a timely manner, and that the tracking system needed improvement. Only seven percent found the system's capability to follow up on complaints satisfactory.

But the community boards' real beef with 311 is that is has narrowed their view of the communities, because they are getting fewer calls themselves. The city is aggravating the situation, they say, by not sharing the information about complaints it's getting, leaving community boards without the information they need to do their jobs.

"We have to evaluate service delivery in our district; we have to make recommendations for renewals for [liquor] licenses and sidewalk cafes. How do we do this without knowing the number of complaints?" said Stetzer.

In response to these arguments, the City Council, through the Committee on Technology in Government, introduced legislation initially over Bloomberg's objections, that will require the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications to provide a monthly report online of complaints registered with 311, broken down by community boards. The law will take effect later this summer. Some community boards see the law as a step forward, but critics say that it will not provide the kind of detailed, up-to-date information that they need to do their jobs.

Menchini says that the law will provide not only community boards, but business improvement districts and private citizens, with information that will allow them to better participate in the problems of their communities.

"By making information available on the web, everybody gets to be a participant," he said. "Everybody gets to understand what's happening."

Â

Arts Funding 101

When Lynn Parkerson, long-time dancer and choreographer, got married and moved from Manhattan to her husband’s home in Brooklyn Heights, she took a look around and said to herself, “why isn’t there a ballet company in Brooklyn?” Brooklyn Ballet was born.

As anybody in the arts will tell you, though, inspiration, talent, drive and even a ready-made audience are not enough. You need funding. Brooklyn Ballet, founded in 2002 and performing for free in Brooklyn schools and public parks, now has a budget of $60,000; the money has to come from somewhere.

That is why Parkerson was sitting with some 75 other heads of non-profit arts organizations at the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs, attending the last of eight seminars the agency gave in all five boroughs on how to apply to it for funds. The arts administrators and artistic directors had just five days before the July 18th deadline for applications.

“For those of you who have never applied before,” Assistant Cultural Commissioner Kathleen Hughes was saying, “give a lot of thought as to whether this is the right time.”

Parkerson, who in fact had never applied before, wasn’t sure it was the right time. “I’d have to pay somebody $500 just to fill out this application,” she said privately, holding up a booklet of about 25 pages. “I don’t have any staff, I don’t have an office, there are so many things that have to get done in the course of a day – I have to go uptown to audition a dancer this afternoon. Doing the programming is a full-time job. Fundraising is a second full-time job.”

The city’s new $50.2 billion budget, which the mayor and the City Council passed on June 30th, and which officially took effect on July 1, includes some $130 million for the Department of Cultural Affairs to hand out to hundreds of non-profit arts groups this fiscal year. The Department of Cultural Affairs gives more money for the arts, officials there say, than any other government agency in the United States, including the National Endowment for the Arts.

The way they do it, however, doesn’t have everybody cheering. “It's inequitable, it's irrational, it doesn't satisfy anybody,” says Norma Munn, who has been following the city’s arts budget since she helped found the New York City Arts Coalition two decades ago. “The bulk of the organizations that get the money use it extremely well,” Munn adds. “But as a city policy, the way it’s distributed just doesn’t make much sense.”

FUNDING FROM TOP TO BOTTOM

“Let me give you a quick Arts Funding 101,” Assistant Commissioner Hughes was saying in the seminar.

“Last year, the agency’s budget was about $120 million, give or take,” she said. “Of that, about $100 million went to 34 organizations.”

1. These 34 are called the Cultural Institutions Group, or CIGs, and range from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which will get more than $22 million in the newly adopted budget, and the American Museum of Natural History, which will get about $17 million, to the Studio Museum in Harlem ($834,000) and the Staten Island Historical Society ($752,000).

The 34 CIGs are at the top of the heap in arts funding in New York City – guaranteed at least 80 percent of the department’s funding year after year.

2. The next level down are 175 arts organizations that are listed by name in the budget (this is called a “line-item” because year after year these same organizations get their own line in the budget). The Bronx Opera Company is slated to receive about $30,000 this year, although it is listed in the executive budget (in pdf format), as the Bronx Opera Society. (“We’ve never been the Bronx Opera Society, and never will be,” says artistic director Michael Spierman.) Among the other organizations with a line are the New Museum (which was promised $22,000 in the executive budget), the Tibetan Museum ($38,000), and the New York School for Circus Arts (almost $115,000). (Final figures for the line-items were not yet available in mid-July.)

While the organizations in this category receive less funding on average than those in the Cultural Institutions Group, there are some individual exceptions any given year. The Police Museum, for example, was listed in the executive budget this year at almost $800,000 (and last year got more than $900,000).

3. Below the line-item groups are those organizations chosen just for this year (with no guarantee of future funding) by an individual member of the City Council or a “council delegation” (meaning all the council members from a particular borough). These are called “member items”, and about 200 groups will get this money in any given year. (The list of these for this year will be available later this summer, officials say.)

Together, the arts organizations in these two categories – the “line items” and the “member items” – get about 90 percent of whatever funding is left after the Cultural Institutions Group. Last year, some 400 groups split about $18 million.

4. The money that remains is offered as part of something called the Cultural Development Fund. It is the only pool of money that the Department of Cultural Affairs awards competitively. The applications are reviewed by one of five peer panels (there is one for each borough), “made up of people like you,” Assistant Commissioner Hughes said at the seminar.

Last year, 550 groups applied to the Cultural Development Fund; 380 of them received a grant of at least $3,000 and at most $15,000. Together these 380 split about $1.8 million – less money than the Brooklyn Children’s Museum (a “CIG”) got all by itself.

It might seem like relatively little money, and the requirements for receiving it are rigorous and complicated (most of the two-and-a-half hour seminar was taken up with explaining how to fill out the application form). But to emerging arts groups, the money -- and the validation that comes with it ("It's the Goodhousekeeping Seal of Approval for the arts," Hughes jokes) -- couldn't be more important. "Every dollar makes a difference," said Monica Harte of The Remarkable Theater Brigade, which produces original musicals for an audience of special-needs children and is applying this year for the first time to the Cultural Development Fund (their first attempt at any government grant). “Three thousand dollars is nearly 14 percent of the budget for our next project -- substantial for us, and crucial to its success.”

A LESSON IN POLITICS

To illustrate what’s wrong with this system, Norma Munn likes to tell the tale of the two Mets: While the Metropolitan Museum of Art (a “CIG”) is getting $22 million this year, the Metropolitan Opera (a “line item”) is slotted for only $134,000.

Those New Yorkers who love paintings more than opera could probably put together a case that the Met Museum deserves over 150 times more city funding than the Met Opera. But Munn’s point is that the criteria for this disparity are not spelled out. It cannot be the size of their respective budgets -- "the Metropolitan Opera actually has a budget that's a little bit larger than the Met Museum" -- and it is not artistic merit: Both are highly regarded.

If the reason for the difference is popularity, then why has the Department of Cultural Affairs given the Police Museum some seven times more funding over the past two years than it has given the New York Philharmonic, and why was the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center, which draws an audience of about 8,000 theatergoers a week, being promised about $17,000 in the executive budget, while the Bronx County Historical Society, which has an attendance of about 8,000 for the entire year, is getting more than $200,000? “It’s not as if the Vivian Beaumont doesn’t need the money,” Munn says. “It most certainly does.”

One reason the Bronx Historical Society gets more money is because it is one of the 34 CIGs.

Being a CIG certainly helps an organization's finances. But what determines whether a non-profit group gets to be a CIG? The arrangement might make sense if the 34 members of the Cultural Institutions Group were the biggest or most important or the most obviously worthy from an artistic point of view – or even if there were some other clear-cut criteria for their selection, such as most needy. But how do you explain the inclusion in the Cultural Institutions Group, for example, of the Bronx Historical Society and the Staten Island Historical Society, but the exclusion of the Queens Historical Society, the Brooklyn Historical Society and the New-York Historical Society? How to explain the inclusion of the Queens Museum of Art and the Museum of the Moving Image, but the exclusion of the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim, and the Whitney?

“It’s a lesson in politics” is how Norma Munn explains it. “The Bronx Historical Society is a CIG and the Queens Historical Society is not, because somebody 25 years ago was smart enough in the Bronx to lobby, and somebody in Queens was not.”

The official explanation is that the 34 members of the Cultural Institutions Group are “owned by the city” (meaning the city legally owns the buildings and the property underneath them) -- though, actually, one of them (the Studio Museum in Harlem) isn’t. The bulk of the money from the city for the CIGs is for “operating and energy support” (heat and light and building maintenance costs) which private donors typically find insufficiently sexy to fund. In exchange, according to Janet Schneider, the executive director of the Cultural Institutions Group, the 34 CIGs have “detailed operating agreements” with the city that require various obligations (different for each institution) that non-CIGs don’t have. “These may entail providing free admission to NYC school children, free or pay-what-you-wish admission, and other free services,” she says.

Critics see the 34 CIGs as largely governed identically to the other major non-profit institutions in New York -- decisions made by independent boards of directors; revenue produced by admission charges or ticket prices, corporate sponsorships, individual memberships and donations; etc. -- and therefore question what "owned by the city" really means.

The rationale for much of the funding for the arts in general, they say, is hidden in history, some of it the result of long-ago horse-trading by long-dead borough-based public officials in a now-defunct city institution (the Board of Estimate).

“The system was built up, ad hoc, over decades,” says Norma Munn, who has been railing for years about it on behalf of her coalition, which represents more than 200 non-profit arts organizations in the city. (See her Funds for the Arts Go Up, But Remain Unfair written in 2000.)

Schneider of the Cultural Institutions Group sees it differently, at least as it relates to the CIGs. The relationship between New York City and the cultural institutions it owns dates back to the 1870s, she points out, a “public/private partnership model” that was needed to create such undisputed treasures as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History. Over the years, she says, the system “has responded to changing needs and changing times...That the city has not abrogated its commitment to the institutions over a period of 130 years is a further testimony to the success of this relationship as arts policy."

Shortly after Kate Levin became the commissioner of Cultural Affairs in 2002, she acknowledged the flaws in the arts budget process at a symposium, co-sponsored by the Alliance for the Arts, an advocacy and research organization.

While she emphasized she was in no way “devaluing the enormous contributions” made by the members of the Cultural Institutions Group, she said “it’s extremely awkward to have a cultural funder that has so little flexibility in terms of responding to emerging needs, emerging institutions, emerging aesthetic trends, etc.”

As for the “line-item” organizations – again with a caveat about the worthiness of many institutions – she said “I was shocked to find that there’s a sizable portion of line-itemed organizations that have gone out of business, and yet their funds appear year after year, and they can’t really be reallocated.”

Since then, Commissioner Levin says now through a spokeswoman, she has been able to reallocate the money from the defunct groups (which were not as numerous as she had thought), and become more responsive to a wide range of cultural organizations especially through the capital budget, which funds major projects such as building renovations and the purchase of vehicles. The new capital budget (in pdf format) will provide more than $800 million over the next four years to help fund such projects for 161 of the city’s cultural organizations, up from 84 in 2002. (Examples: $29 million for Lincoln Center, $1.6 million for the Brooklyn Academy of Music, $87,000 for the Louis Armstrong House, $25,000 for P.S. 122 Theater in the Bronx.) "The agency is always looking at ways to make money more available to groups, and to respond to emerging needs."

If the expense budget remains far less flexible, even Norma Munn concedes that it would be difficult to change it. “To fix the system would require either taking money away from institutions that are getting it now, which would be politically unfeasible,” Munn says, “or increasing the total amount of money available for the arts, which the mayor is not likely to do.”

FUNDING SOURCES, RESOURCES AND RESOURCEFULNESS

The mayor has increased the total amount of money available for the arts – from his own pocket. For the fourth year in a row, he has given an “anonymous” gift (reported in every local newspaper) to the Carnegie Foundation of New York – the accumulative amount is $55 million -- to distribute grants to a list of hundreds of groups in the five boroughs, including about 230 arts and cultural institutions.

As for the total amount of money available for the arts from the city government that he heads, the adopted budget -- as predicted(see section entitled "The Budget Ballet"), and despite the huzzahs over City Council-backed "restorations" -- includes about one quarter of one percent for the arts, just about the same percentage as ten years ago under then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani.

In a city that is the capital of culture – and the capital of capital -- money for the arts does not just come from the government, as officials at the Department of Cultural Affairs are the first to point out.

"Who Pays For The Arts?", a study in 2001 by the Alliance for the Arts of 575 organizations that applied for funding from the Department of Cultural Affairs, found that on average, their revenue sources were

- 51 percent from earned income, such as ticket sales (this went down to 39 percent on average for the smallest institutions, those with budgets under $100,000)

- 38 percent from private sources (such as contributions from individuals, corporations and foundation grants).

- 11 percent from government (this went up to almost 28 percent on average for the smallest arts groups).

A reason for the relatively small percentage of revenue from government grants, the report observes, is simply that the government has been cutting back -- though, the report concludes, that money is not being replaced (as was the hope and the prediction) by an increase in corporate donations.

“Government” does not mean just the Department of Cultural Affairs. Funds for the arts are available from federal agencies (National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, etc.), state agencies ( the New York State Council on the Arts, New York State Natural Heritage Trust, New York State Department of Education, etc.), and other city agencies, such as the Department of Youth and Community Development and the Department of Education. While the Department of Cultural Affairs will only fund arts organizations that have been around for at least two years, there are five borough arts councils that are open to groups with less of a track record.

But the most helpful advice (and most revealing comment?) during the funding seminar at the Department of Cultural Affairs may have come when the assistant commissioner was explaining that this year’s cultural budget includes $8 million of “member items” – picked by individual members of the City Council.

“The council members have the ability to fund your organization -– if they know of your organization,” she told the group, as she handed out a contact list of the council. “One of the things you need to do is reach out to those council members.”

That is one of the first things Lynn Parkerson did, after she put together a board of directors and got non-profit status for Brooklyn Ballet. On the recommendation of a fundraising consultant, she was able to wrangle some of her first funding from the council.

She did this by meeting with the council member from her district, David Yassky, who invited her to be one of the many beseeching groups to give a five-minute presentation at the next meeting of the Brooklyn delegation. This is where she won over Lew Fidler, who arranged funding (not through Cultural Affairs but a different agency) so that she could offer a ballet program in six schools in his district.

What won him over?

“I brought two dancers along, and we gave a real performance,” Lynn Parkerson said. She discovered early, then, how much arts funding in New York depends on a political dance.

Â

Being Borough President

Borough President Races: |

John Nance Garner, Franklin D. Roosevelt's vice president for two terms, famously commented that the number two office in the land wasn't "worth a pitcher of warm piss."

So what would Garner make of New York's five borough presidents? This is, after all, a job whose occupants Rebecca Meade likened in the New Yorker to "neutered beasts."

The office does offer the trappings of power -- a lofty title, $135,000 a year salary, a driver and sometimes a palatial office - but without much real authority anymore. Nevertheless, dozens of politicians are raising money, issuing press releases and spending endless hours shaking hands at subway stations in the hopes of capturing the job. As candidates scrambled to meet the July 14 deadline for filing petitions to get on the ballot, 24 candidates were vying for the five jobs.

And this year is less competitive than most. In every borough except Manhattan, a sitting president wants another term. Given the notorious power of incumbency in New York this undoubtedly scared away many potential challengers. It did not, however, keep the campaign donors away. As of July 16, two of the incumbents - Adolfo Carrion of the Bronx and Marty Markowitz of Brooklyn - had raised more than $1 million for races in which, many observers say, they face little credible opposition.

But the real action is in Manhattan. Fourteen candidates are seeking to replace C. Virginia Fields. It is, as one of them said, an open seat -- and those don't come up very often.

FADING POWERS

|

|

|

| (From left to right) • Carlos Manzano • Eva Moskowitz • Brian Ellner • Scott Stringer • Adriano Espaillat |

The office of borough president was created at the time of the consolidation of Manhattan, the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island into the City of Greater New York in 1898. (Before that, "New York" was just Manhattan and parts of the Bronx.) The idea of borough president, the charter said, was to preserve "local pride and affection." Brooklyn had just been forced to surrender its status as a separate (and major) American city, and Queens and Staten Island were still largely rural.

Three years later, the borough presidents gained considerable clout in a revision of the city's charter, becoming five of the eight members of the Board of Estimate, which controlled the city budget and had power over building projects.

But the presidents' heyday drew to an end in 1989. Because the borough president of Brooklyn with more than 2 million residents had the same number of votes on the board as the borough president of Staten Island with a population of about 380,000, the United States Supreme Court ruled that arrangement unconstitutional, violating the principle of one person-one vote. To address the ruling, another charter commission eliminated the Board of Estimate and expanded the City Council. But they kept the borough presidents. They did this because of "a feeling by at least some people that there needed to be some level of government between the City Council and the mayor," said John Mollenkopf, director of the Center for Urban Research at the City University of New York Graduate Center. And, he said, the politics of eliminating five high-profile political positions was considered more trouble than it was worth.

Every borough president still got to appoint one member to the powerful central Board of Education. But even that vanished with the advent of mayoral control of the school system -- and the dismantling of the Board of Education -- in 2002. This capped what Mollenkopf called "a long steady decline in the power of borough president since the time Greater New York was fashioned in 1898."

Today, the borough presidents make a few appointments -- to community planning boards, the planning commission and various other agencies and task forces - chair the borough boards, and oversee the delivery of services in their boroughs, though with limited power to fix whatever might be wrong. They can propose legislation in City Council, recommend some capital budget expenditures and dispense some money within their borough.

There have been no loud protests over the diminution of their power. After all, more than a century after consolidation, while some New Yorkers still feel that "pride and affection" for the borough in which they reside, most see themselves, first and foremost, as New Yorkers: Adults cross borough boundaries every day to go to work and children to go to school; congressional and city council districts straddle borough lines; only one daily newspaper (the Staten Island Advance) caters to a specific borough.

"You could do away with the borough presidency and I don't know if the nature of New York City politics and policy would change," said Doug Muzzio of the Baruch College School of Public Affairs.

"The office doesn't do much," admitted Joseph Dobrian, the Libertarian candidate for Manhattan borough president.

"It really doesn't serve any government purpose," said a writer named Ann Noonan, who wrote a paper a few years ago calling on the city to eliminate the office of the borough president, arguing "New York City's budget cannot afford these ceremonial disbursements of roughly $37 million," and presented it to the charter review commission. People praised her proposal, she says now, but it went nowhere.

WHAT THE CANDIDATES SAY

|

|

|

| (From left to right) • Magarita Lopez • Bill Perkins • Stan Michels • Marty Markowitz • Helen Marshall |

Aside from Dobrian, most candidates for the office argue it does have clout, with influence far beyond the official duties.

"It's a bully pulpit. It's advocacy. You need to be very vocal," said Brian Ellner, a lawyer who is one of the candidates for Manhattan borough president.

The borough presidents serve as cheerleaders for their borough, trying to attract investment and new projects. Staten Island President James Molinaro boasts of creating parks and limiting development, while Helen Marshall of Queens talks up the new Mets stadium planned for her borough and Adolfo Carrion says he has created new jobs.

Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz has become the cheerleader par excellence, such an abashed booster of Brooklyn's food, people and neighborhoods that he was featured in a New Yorker magazine profile. Markowitz also takes the credit - or blame - for persuading developer Bruce Ratner to propose an arena in downtown Brooklyn for the Nets basketball team. "Bruce had no interest, absolutely no interest," Markowitz told the New Yorker. "But I was very persistent with him, and didn't take no for an answer."

Even Marty Markowitz, though, has been known to admit that his main powers extend to handing out certificates of appreciation to Brooklyn citizens and dispensing Junior's cheesecake.

Borough presidencies do indisputably accomplish two things. They provide plum elected office for five politicians and jobs for some of their associates. And they can be a path to higher office. Mayors Robert Wagner and David Dinkins first served as Manhattan borough president, as did mayoral candidates C. Virginia Fields, Andrew Stein and Ruth Messinger. Robert Abrams went from being Bronx borough president to being state attorney general, while another Bronx borough president, Herman Badillo, moved up to U.S. Congress. Today, former Bronx borough president Fernando Ferrer is running for mayor, while his successor, Adolfo Carrion, has already announced his plan to try for Gracie Mansion in 2009.

That, more than anything else, may be why the office of borough president persists. "Politicians want it because it's a stepping stone," Muzzio said. "What else would these people run for?"

Â

Think Locally, Act Regionally

A queen and three prime ministers descended on Singapore last week to lobby the International Olympic Committee on behalf of New York’s rivals to play host to the 2012 Olympics. President George W. Bush did not go, appearing only briefly in a video, and neither did any other Bush administration officials.

A queen and three prime ministers descended on Singapore last week to lobby the International Olympic Committee on behalf of New York’s rivals to play host to the 2012 Olympics. President George W. Bush did not go, appearing only briefly in a video, and neither did any other Bush administration officials.

Indeed, of the five cities competing for the prize, only New York did not have the obvious and vigorous backing of the nation it represented.

To many New Yorkers, Washington’s inattention was typical – symbolic, in its own small way, of a lack of federal support for the city that has been evident for at least a generation.

Such federal indifference is one reason why progress has been so slow on a range of local issues, whether rebuilding Ground Zero or housing newcomers. It helps explain New York’s inability to finish numerous transportation projects important to the city and the region -- the Moynihan Station, which is supposed to replace Penn Station by converting the post office across the street; the Second Avenue subway, which has been planned for decades (some tunnels for it were built in the 1960's); the East Side Access Project that would create a direct link between the Long Island Railroad and Grand Central Terminal.

This was not the way things used to be. Federal aid during the New Deal built familiar landmarks like the Triborough Bridge and LaGuardia Airport, and created the city’s network of neighborhood parks. Massive flows of federal money for housing in the post-war years resulted in the row after row of hulking, unadorned apartment buildings that rise along the eastern edge of Manhattan or stand beside the Rockaway surf.

By contrast, in the tradition of the Daily News headline, “Ford To City: Drop Dead!”, Republicans in Congress last year tried to rescind money allocated to Moynihan Station.

Many consider a tilt against New York inevitable, given that electoral college map that was shown over and over during last year’s election, with its sea of red surrounding the blue islands like New York. Some New Yorkers believe they are simply on the wrong side of a majority with an anti-cosmopolitan attitude and an anti-urban agenda.

But the truth, as we see it, is more nuanced, and more hopeful.

Granted, New Yorkers like to view themselves as unique and apart, connected to the United States only by the tiniest landmass at the northern end of the Bronx. But, in truth, New York remains very much linked to the larger tri-state region that includes New Jersey and Connecticut. The New York area’s jam-packed bridges and tunnels testify to this. Commuters to Manhattan supported approximately $70 billion of New York City’s economic output in 2000, according to the Regional Plan Association, while, for its part, New York City generates more than 40 percent of the region’s wages. Surely these interconnections can trump division in times of need.

At the same time, there has emerged an archipelago of huge, fast-growing “super-regions” across the nation that are coming to resemble (at least a little) the New York urban region in terms of sheer size and diversity and infrastructure needs. They have given New York a larger set of super-sized cousins -- and potential allies.

FORGING LINKS

How might New York prevail?

We suggest two ways to transcend the balkanized local politics of authorities and mayors on the one hand, and the seemingly inhospitable calculus of the red-blue map on the other.

Look To The States

First, New York and tri-state residents should look much more than they have to the tri-state capitals -- Albany, Trenton, and Hartford -- to collaborate to meet their needs.

This is already starting to happen. Concern for the future of Amtrak, for example, has already drawn state leaders from across the tri-state region into successful common cause. The need to protect air quality and watersheds has enlisted all three states’ attorneys general in a nine-state lawsuit challenging Bush administration regulations that exempt coal-fired power plants from tough controls on mercury pollution. And in the wake of the London terror attacks last week, Governor M. Jodi Rell announced that Connecticut had joined New York Governor George E. Pataki and New Jersey Governor Richard J. Codey in a tri-state agreement allowing troopers from each state patrol onto the commuter trains into New York City, retaining their arrest powers.

True, the slow progress of projects like the Trans Hudson Tunnel or the Cross Harbor Rail Freight Tunnel (whatever one thinks of those proposals) underscores how frequently regional initiatives fall victim to either the horse trading of Albany (or Hartford or Trenton) or bickering between the states.

But on many issues the states matter far more to the health and prosperity of their metropolitan areas than Washington does. This is why New Yorkers should insist that multi-state collaboration widen to address such common priorities as federal and non-federal housing policy; the defense of critical worker benefits like the earned income tax credit (EITC); and the region’s fundamental infrastructure.

Imagine the creation of a regional, multi-state pool of capital dedicated to the preservation and modernization of the infrastructure--airports, ports, passenger rail, roads, bridges.

Or consider the founding of a new multi-state fund dedicated to the remediation and reclamation of polluted land along shared waterfronts.

Or picture the establishment of a new regional, multi-state pool of worker training funds to prepare workers for a knowledge economy that has no respect for political or administrative borders.

Where would the new funds come from? They could come from a regional armistice on tax abatements and other government subsidies used to lure companies and firms from one side of the region to the other. Or perhaps the three states (with similarly motivated allies out West or in the South) should pile onto Felix Rohatyn’s recent proposal of a $100 billion federal trust fund, to be financed by special 50-year Treasury bonds, to finance high-priority state and local investment programs, including physical infrastructure.

In this way the region would take the lead in pressing for the restoration of the traditional federal-state commitment to investing in the physical and intellectual infrastructure of America’s regions.

Look To Emerging Super-Regions

But intra-regional collaboration, as important as it is, can only go so far. Beyond it, the tri-state area needs to look outward, and locate common ground with other urban super-regions of the country in ways that confound popular perceptions of the political divide.

This, too, has already happened, to some extent, with the blunting of Bush administration efforts to defund Amtrak by a bipartisan confederation of Northeastern, Midwestern, and Californian representatives in the House last month.

But the opportunity is larger. The titanic demographic and development changes sweeping the nation are creating massive “new” regions of shared interest. Scholars have identified from eight to 10 huge “megalopolises” (in pdf format), gargantuan region-scaled growth zones organized around major interstate highways, across the country. These include, for example:

- The Phoenix metroplex

- the I-35 corridor in Texas that encompasses a string of metropolitan areas running from San Antonio in the South through Dallas to Kansas City in the North

- Greater Atlanta and the Piedmont region

- The Colorado Front Range

- Houston, New Orleans, and the Gulf Coast

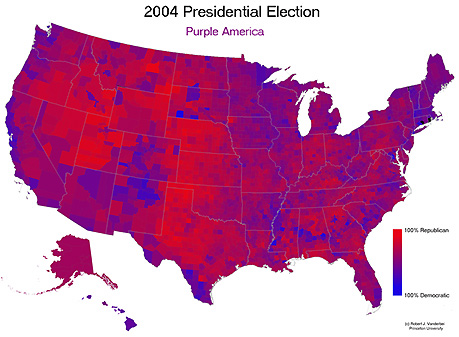

Such mega-regions now encompass more than 70 percent of the country’s population and extend into 35 states. They will add seven of every 10 new Americans by 2040, and three-quarters of the capital to be expended nationally on private real estate by then. They went for John Kerry over George W. Bush (by 51.6 percent to 48.4 percent) in 2004.

As such these newer conurbations represent a huge opportunity for alliance-building, in Congress or on other fronts, whether on highway construction, workforce development, transit, or port and security activities.

Shared Interests Among Super-Regions

Look at immigration patterns. The immigrant gateways (in pdf format) of the past 20 years include traditional places like New York City, Chicago and Los Angeles but also newer places like Charlotte, Atlanta, Houston and Phoenix. This last may help explain why Arizona’s congressional delegation is the driving force behind a sensible “temporary worker” proposal that (unlike President Bush’s version) would allow New York’s many undocumented immigrants to keep working on three-year permits and enjoy other rights, while also providing them a clear path toward a green card.

Or take infrastructure needs, particularly the interest in mass transit. The newer, fast growing cities of the Sun Belt are having the same kinds of discussions around cores and corridors that the New York metropolis had 80 years ago. Colorado may have voted for Bush 52 to 47 percent in the last election, but during that same election, voters in the Denver metropolitan region overwhelmingly passed (58 to 42 percent) a referendum to raise $4.1 billion for a 118-mile light rail system. (Significantly, four counties that voted against Kerry supported the transit system.)

Or even take social policy. Our analysis of residential patterns of low-wage workers in the country shows an incredible confluence between the densely populated cities of the Northeast and Midwest and rural areas in the South. Listening to the political class, one would never realize that constituents of legislators in Mississippi have as high a stake in the policies that make work pay -- the Earned Income Tax Credit, child care, and health care coverage -- as residents of New York City, Newark, and Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Or consider the needs of urban counties. America contains some 64 older suburban or “first suburban” counties -- denser, longer-established suburbs (often in the Northeast) that now face truly urban challenges yet which frequently reside in a policy blind-spot because they are neither poor enough to qualify for most federal urban programs nor new enough to tap federal and state programs that focus on building new housing and infrastructure. Predictably, this slice of America contains such familiar places as Nassau County in Long Island, Essex and Hudson counties in New Jersey, and Fairfield County in Connecticut.

But dozens of these “urban” first suburbs now dot the rest of America, where Fulton County surrounding Atlanta, Harris adjacent to Houston, Los Angeles County and Dade County, Florida all stand as fellow “first suburban” communities.

What is more, these 64 counties now house over 52 million people and comprise nearly 20 percent of the American population. That means that close to 50 percent of the American population -- almost a majority of Americans -- live in traditional central cities and five dozen or so urban counties.

Clearly, metropolitan New York does not stand alone in facing large urban challenges. A growing swath of America now shares a common agenda around infrastructure, social policy, and competitiveness writ large. Phoenix and Dallas may soon rank almost as important as Albany, Trenton, and Hartford in what needs to become a canny new regional strategy for prevailing in an unfriendly political moment.

Redrawing the Map

It’s becoming clear that while the red-blue map depicts an unfavorable Washington politics, it tells only part of the truth.

More accurate, particularly as the new mega-regions grow and urbanize over vast multi-county landscapes, is the so-called “purple map” produced by Robert Vanderbrei of Princeton University which shows, at the metropolitan or local scale, that far more of America consists of evenly split than sharply red or blue districts.

On this map, competitiveness, not one-party domination, is the norm. Metropolitan areas and mega-regions -- with their more favorable political priorities and infrastructure needs -- spread wider and wider and hold out opportunity.

And so Senator Charles Schumer was exactly right when he bemoaned the onset of a “culture of inertia” in Albany and New York recently. But beyond just parochialism and gridlock, New Yorkers are indulging in something much worse -- pessimism. That must change, if one of the world’s great megalopolises is to respond to the challenges being mounted by urban regions around the world, as they spend billions on new rail spines, economic development, and urban regeneration.

Instead of bemoaning the red-blue map, shouldn’t the New York region simply redraw it? By collaborating across state borders and finding common-cause with the nation’s other mega-regions, the New York super-region ought to be able to forge a new and powerful super-alignment that could actually transform current politics.

Bruce Katz is director and Mark Muro policy director of the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution.

Related Articles

NY's Concerns Can Be of National Concern Once Again By Ester Fuchs

Boss Tweed

Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club held a conversation on June 22 at the Jefferson Market branch of the New York Public Library with Kenneth Ackerman,who has worked for both the executive and legislative branches of the federal government and is the author of several books, most recently "Boss Tweed: The Rise and Fall of the Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York." An edited transcript appears below:

Kenneth Ackerman(reading from his book): [William Magear] Tweed didn't invent civic corruption or ballot-box stuffing, but he and his Tammany crowd elevated the techniques to stunning proportions. They committed frauds gigantic on any scale, even if Tweed was personally guilty for only a small fraction of the whole. In later years, estimates of "Tweed Ring" total plunder jumped from the relatively modest $25 million to $45 million of the 1877 Aldermen's Committee to fully $200 million ($4 billion in modern dollars), a figure clearly inflated for dramatic impact but never scrutinized. It became part of the legend.

Tweed lived in a corrupt time, the Gilded Age, but he defined that era and pressed its boundaries. Even by his own day's standards, to call something "A Worse Fraud than Tweed's" spoke volumes. Tweed inherited a culture of graft endemic to New York City for generations and pushed it to its logical extreme, forcing the reformers to crack down.

After his excesses, no city in America could any longer tolerate wide-open graft or ballot-box abuse. Urban corruption didn't disappear, but it evolved and became more subtle. "A villain of more brains would have had a modest dwelling and would have guzzled in secret," E.L. Godkin wrote in the aftermath. George W. Plunkett, a Tammany leader of the next generation, well understood the point. "The politician who steals is worse than a thief," he'd say in 1905. "He is a fool."

TWEED IN PICTURES

So much of the Tweed story is visual. It is a story about the role of the media and the role of images, pictures, and cartoons. You can't really tell the story without the images. Tweed's persona was very much shaped by cartoonist Thomas Nast. Nast was a little too good at what he did. He was so clever and so vivid and wrote such funny compelling cartoon images that it was hard for Tweed, either in his lifetime or for posterity, to get away from the image Nast had created. I hope I've done a little bit to free Tweed from that stone around his neck.

Some of the pictures drawn of Tweed hit the nail on the head, and some don't.

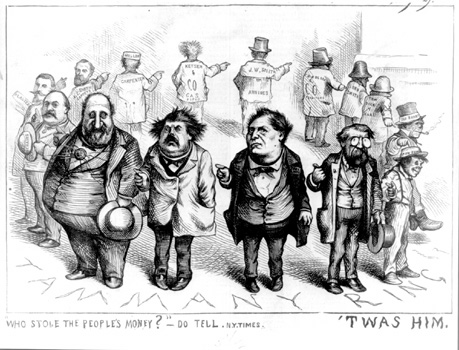

This is my personal favorite of the Nast cartoons, and it's one of the most famous of them. It was drawn just after the New York Times broke the story and they put out the so-called secret accounts, which showed the money the city paid for various contracts related to the Tweed courthouse. They were so big that it was impossible to believe the stories were true.

One example was the sum that was supposedly spent for chairs. It was enough to buy something like 315,000 chairs, so that if you lined them up in a row they would have made a line 17 miles long.

What the New York Times didn't show was who stole the money, or how the system worked. Even with the disclosures the Tweed ring could still feel that if they could keep silent they could still get away with it. Thomas Nast's cartoon, drawn right after that disclosure, shows this. Tweed himself is Nast's image of the American politician: big, fat, and arrogant with a silly look on his face, kind of ugly. Nast put looks on his characters' faces so that you'd always recognize them, kind of like Daffy Duck or Bugs Bunny. They're very distinctive pictures. The famous diamond that Tweed's friends gave him for a Christmas present was always on Tweed's chest in the cartoons. It was ten and a half karats, valued at $15,000 in 1870 money; that would be about $300,000 in modern money.

What you see is the Tammany ring, Tweed, Sweeney, Connelly, and the mayor Okie Hall all standing in a circle with the city contractors. Nash was notoriously bigoted and prejudiced towards the Irish and Catholics, and these characters are typical Irishmen for Nast: looking kind of like a gorilla, big square jaw, smoking a pipe, a whiskey bottle nearby, looking kind of nefarious. It's labeled: Tammany Ring. The caption says "Who stole the people's money, do tell." And everyone is pointing to the guy next to him and is saying 'Twas Him.'

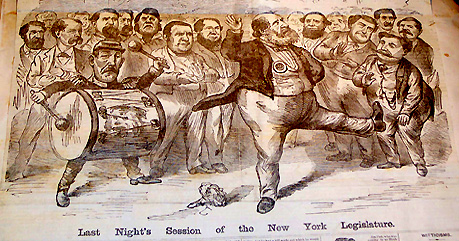

This was drawn by a friendlier artist. It shows a ball thrown by the Americus Club, which was Tweed's social club. Every year they rented out the New York Academy of Music on Union Square and threw a big party.

Here you see Tweed looking large but graceful, the center of attention, with people looking on in admiration. He's dancing a jig; he has a presence in the room. In real life he was about 300 lbs. Eating was the one major vice that he admitted to. He didn't smoke and he rarely drank, although when friends would come to visit he would always be ready with the cigars and whiskey bottles to give out favors.

Tweed was someone who, when he came into a room would work the crowd, make sure he got to know everyone. He would go up to you, shake your hand, tell you a story, share a joke, pat you on the back, and make sure by the time the night was over he knew your name, your family, what you did for a living. He would probably find some way to do you a favor, knowing that in this political world if he did a favor for you, you would do one back for him. He was the kind of person who if he promised to do something for you, you could have confidence he would do it; he had a very good reputation for, of all things, honesty.

That's the image of Tweed that I like in many ways more than Nast's, though they're both true. Part of the irony of Tweed is that it's wrong to be an apologist for him. You can't simply minimize what he did, and say 'everyone stole so it's not a big deal'. He stole much more than anyone else, but he had a big enough personality that the warm bloodedness of him, his effort to make right by the people around him, was just as prominent as the stealing. It may have been manipulative, it may have been pragmatic, but so what?

|

This cartoon is from 1875, also by Thomas Nast. It has a picture of an old brick building that served as the city jail. Tweed is shown as a giant too big to fit into the building. His head is sticking out one end and his feet the other. And the caption says "stone walls cannot imprison me, no prison is big enough to hold the boss, in on one side and out at the other."

Nast drew this drawing right at the time of Tweed's famous jailbreak. By 1875 Tweed recognized he was never getting out of jail, and he decided enough was enough. He paid about $60,000 in bribe money and arranged to sneak away. Ultimately, he made it as far as Cuba and then Spain before being re-arrested. He was on the run for about 10 months, mostly at sea. The Spanish authorities used Nast cartoons, including this one, to make the identification.

John Guzman: Is the implication that [President Ulysses S.] Grant had something to do with the escape and capture of Tweed correct?

Kenneth Ackerman: Definitely with the capture. The State Department got wind of where Tweed was when he landed on Cuba. At that time, early 1876, the presidential election had started. New York Governor Samuel Tilden was running against Rutherford Hayes, and there was a hope that if Tweed could somehow be captured and brought back to New York City he could be used as a weapon against Tilden.

So Grant arranged for Tweed to be captured and brought back on a very fast ship. Tweed managed to get wind of it and slip away in Cuba but Grant arranged for the Spanish to hand him over and send him back. The reason the attempt to use Tweed against Tilden fell through was that Tweed's trip back across the ocean was plagued by very, very bad weather and it took them twice as long as they expected.

As far as Grant or others being implicated in the escape itself, this gets into the realm of the very mysterious. There was clearly a helper, a man name Hunt, who joined Tweed in Florida and became his personal guide as they traveled through Cuba and then Spain. Who this Hunt was is one of the great mysteries of the whole story. When he was arrested in Spain along with Tweed they were originally both to be extradited to New York City. But at the last minute instructions came from Washington through the State Department to the American ministry in Spain saying "we want Tweed only, we don't want Hunt." So Hunt was let go. And it has always been a mystery who this person was.

TWEED'S LEGACY

Gotham Gazette: In the title of your book you say that Tweed "conceived the soul of modern New York." What do you mean by that?

Kenneth Ackerman: I was looking at personality. I saw in Tweed a person who was bold and smart and brassy. Whatever he did was the biggest, the most and the boldest, whether it was the way he went about fixing an election, or the house that he built on 5th Avenue, or the way he paved the streets, or the wedding he threw for his daughter.

In the State legislature, Tweed was one of 32 members when he joined it in the late 1860s; within a year he was the most important member. Not just because he was bribing other members, but because he was chairman of its two most important committees. He was the person who was involved in patronage, not just for New York City but for the canal system upstate. And that's where I come up with the "one who conceived the soul of modern New York." This is his city. This is the biggest city in America, and Tweed would be very comfortable with people who say that if it is not in New York it is not very important.

Gotham Gazette: So by "soul" you mean basically the bigness of it?

Kenneth Ackerman: The bigness, the personality, the energy, the confidence, to some extent the arrogance. It's part of our national persona as well, but New York had it first and demonstrates it the most.

Gotham Gazette: On the front page of the New York Times today, there is an article about Albany which lists, scandal by scandal, the corruption that's still going on. It mentions Guy Velella; it mentions an aide to the governor who gave a contract to a friend running a non-existent company; it mentions former US Senator Al D'Amato, who was paid $500,000 to make a simple phone call. Is there some of Tweed in that as well?

Kenneth Ackerman: There's some of Tweed in that. The political corruption lives at all levels today as it did then, although not in as outward form. There are more checks and balances today on corruption than there were in the 1860s and 1870s, probably because of Tweed. Today there are ethics committees in legislatures, and law enforcement is much more developed. The amount of record keeping that goes on for legislators' gifts, for instance, makes it much more difficult to be corrupt on that level. The cash accounting in the city government is worlds more advanced than it was in the 1870s. For someone to try to steal a billion dollars today from New York City, I'm not going to say it's impossible, but it would certainly not look like what Tweed did.

The places where you do have corruption on that level is in the corporate world.

What's similar is that the incentives are still there. Even though you don't have legislative bribery the way you did during the Tweed era in the state legislature, the amount of money that today goes to pay for members of Congress and United States senators and their campaigns is to some extent outrageous, even though it's legal.

Gotham Gazette: How about for mayor?

Kenneth Ackerman: It's still early in the mayor's race, so we'll see how that one goes. Mr. Bloomberg is bringing a lot of his own money to this.

What I do think is interesting is how much money city taxpayers pay for sports stadiums for teams that make tens of millions of dollars a year. We recently had a discussion about this in Washington D.C. where the city government is ending up paying $800 million for a new stadium for the Nationals baseball team. When they tried to fight it, Major League baseball threatened to pull the team out of town and the city caved. New York City had a lot more backbone on this than we did.

Gotham Gazette: But are the stadium issues Tweedian in some light?

Kenneth Ackerman: Well it is and it isn't. When I call something "Tweed-ish" to me it's not necessarily an insult. Something like the Jets stadium has Tweed written all over it. Tweed loved big projects that cost a lot of money, such as the Brooklyn Bridge or a large new building. He liked things that would employ hundreds or thousands of people, would send money to dozens of subcontractors and businesses, and would develop the economy in a part of the city.

Now certainly in Tweed's day there were cuts and padding all along the way, and jobs could be directed to your friends. Today there are union contracts and contracting rules that control that to some extent. So I don't think the dishonesty is there to anywhere near the extent in the Tweed Era. But the idea of big public works projects designed to keep people employed worked for Tweed and works today.

A lot of what Tweed built turned out in retrospect to be very useful. It was basically the infrastructure of the city, the sewer lines, the bridges, the parks, the sidewalks, things that have a lot of use. The question, which is a question of judgment, is whether a sports stadium 50 years from now is going to be considered useful.

Martha Soffer: Did Tweed have any influence on Robert Moses?

Kenneth Ackerman: There are some similarities to Robert Moses, caveat the corruption. But large-scale building was Tweed's signature, as it was later to become Moses' signature. Whether Tweed would have had the same attitude about breaking up neighborhoods is a whole other question. Part of the controversy with Robert Moses is that he felt so strongly about building highways that he was willing to run a path right through the middle of the South Bronx or right through the middle of Midtown Manhattan, regardless of the side effects that that would cause. Whether Tweed would have been more careful is a hypothetical question. We don't really know the answer. He obviously built a lot of big things but he was also someone with his ear to the ground in the neighborhoods, because he knew that was his base of support.

TWEED'S SYSTEM

Gotham Gazette: Your book deals mainly with Tweed's crimes. But Pete Hamill wrote in the New York Times that "One thing was certain: because of Tweed, New York got better, even for the poor." You seemed to be alluding to that. Do you agree with that, and what do you think were Tweed's main tangible accomplishments, aside from getting rich?

Kenneth Ackerman: Well, getting rich is an accomplishment. But I do agree with Hamill; part of the beauty and the irony of Tweed's system was that when it was working it did seem to work for everyone. The Tweed ring, when it ran city government, kept taxes low while spending lavishly on city improvements. Property values were up all over town.

It was a little like the era of the 1990s: the economy was very good and the stock market was on a roll. This was the period right after the Civil War, when railroads were having a boom, and telegraphs and even agriculture were having a good decade, and all of that money came into New York City. So there were a lot of factors causing the boom, but Tweed was encouraging it, he was riding it, and he was spending that money on the city while keeping taxes down.

As a result the city's wealthy class very much supported him. When he first got in trouble with the New York Times, he was able to get a group of city elders led by John Jacob Astor III, one of the wealthiest men in town, to go and look at the city books and publicly give them their blessing. At the same time Tweed did a lot of positive things for the poor, bringing immigrants into the political mainstream. Even though that may have been a cold-blooded pragmatic deal, it worked for the benefit of all. He was very loyal in terms of rewarding his friends, giving jobs to backers of his party.

When people, primarily Irish immigrants, would come out on election day and vote ten, twenty, thirty times that was not considered something to be embarrassed about. That was something many were proud of; it was your way of breaking in as a party worker. That would be a way for you to get a city job, to put bread on the table for your family, and to be part of the American mainstream. There are descriptions of these large demonstrations for Tweed either in Union Square or Tweed Plaza at what is at Canal St. and East Broadway. People would march behind placards saying "Tammany repeater."

But the picture is not complete unless you mention that there was a big crack in the middle of it. A lot of the money that was being spent, both for good and for bad, came from borrowing. It came from outsiders. Basically, Comptroller Richard Connolly financed the city by issuing dozens of kinds of stocks and bonds: park improvement bonds, courthouse improvement bonds, street improvement bonds, literally dozens of kinds that were being sold to Wall Street and to investors in Europe. In the three or four years that Tweed and his group were in control the city debt rose from about $30 million to close to $100 million. That was the crack in the system. It's a little bit like a cock-eyed Robin Hood. Tweed is like Robin Hood, if you assume that Robin Hood steals from the rich but keeps the first third for himself, gives the next third to the merry men, gives another cut of four or five percent to the local newspapers in Sherwood Forest to write good stories about what he does, encourages the poor to join the merry men so they can get a part of the take, and then gives the rest to the poor. Assume also that he doesn't steal from the rich in Sherwood Forest, but from the rich people two forests over. There you have Tweed.

Joan DeCamp: I'm interested in the stocks as a way to raise money. Today that would have to be done through public referendum, or by going through Albany. What was the political structure that would allow them to do this, and what eventually became of those bonds? I'm assuming that the robber barons and their friends knew better than to buy these.

Kenneth Ackerman: The way the city government structured itself was very different. Up through the late 1860s, Albany had gotten very involved in city government: it controlled the city legislature, it created a board of supervisors with 12 members (6 Democrats and 6 Republicans) which was supposed to make the city clean. Generally you could raise bonds almost by fiat if you could get the approval of the mayor and the comptroller.