That 70's Show

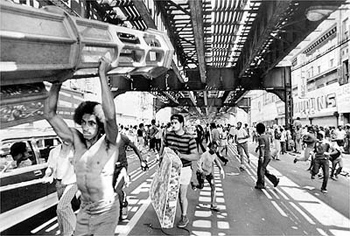

Heavy looting followed a citywide blackout in July 1977 |

Jonathan Mahler met with the Gotham Gazette Reading NYC Book Club at the Jefferson Market Branch of the New York Public Library on April 27 to discuss his book "Ladies and Gentlemen the Bronx is Burning: 1977, Baseball, Politics, and the Battle for the Soul of a City." Mahler argues that the year was a turning point in the city. The edited transcript is below.

Gotham Gazette: This month we are with Jonathan Mahler who is a contributing writer to the New York Times Magazine. His book Ladies and Gentlemen the Bronx is Burning is about the events of the summer of 1977 in New York City. Mr. Mahler is going to begin by reading a passage of the book about the blackout.

Jonathan Mahler: The book is about the year 1977 in New York. I chose that year because, from a narrative perspective, it was very eventful: mayoral race, blackout, [serial killer] Son of Sam, many other things. But also, from a broader perspective I chose that year because it was a pivotal moment when New York went from being one kind of place to a different kind of place. I guess you could say the old New York - this quasi-socialist city with the great free higher education, rent controlled apartments, lots of jobs for the working class - was dying and a new capitalist utopian city was being born. That's the city we live in, with real estate barons and media tycoons and the like.

THE BLACKOUT

I devote a lot of space to the blackout in the book. I tell much of the story of the blackout through the eyes of a group of cops in Bushwick, Brooklyn, which was the neighborhood that experienced the worst looting that night. I had the good fortune to meet these guys as I was researching the book. Obviously, it was a night they couldn't forget, so they all had specific and detailed memories. The narrative that I am going to be reading I was able to piece together through the accounts of these guys.

(reads passage starting on page 187).

Gotham Gazette: How did the blackout and the riots serve as a turning point or the low point of New York at that time?

Jonathan Mahler: Well, this all happened in the heat of a mayoral race. At the time of the blackout, this little-known long-shot congressman named Ed Koch was running for mayor. And his competition, the front-runners were, of course, the incumbent Abe Beame, Bella Abzug, and Mario Cuomo, all of whom were far ahead of him in the polls. But after the blackout, Koch - who was not terribly well known as I said - was able to kind of, for lack of a better word, exploit the bloodlust in the city in this sort of fear of crime. And he ran a real law-and-order campaign, which ultimately led to his election. He campaigned for the death penalty, [even though] mayor has no say in whether or not New York State adopts the death penalty. But it became a campaign issue. Mario Cuomo was adamantly opposed to the death penalty.

One thing Koch criticized Beame for was not bringing in the National Guard in during the blackout. So it became a campaign issue.

I think if one takes a broader view, at the time, the New York City Police Department was really depleted because of the fiscal crisis. And there was not a lot of good will toward the police department, because as a result of those layoffs, there had been a lot of police protests, which people don't like to see. There was one police protest at Yankee Stadium. And while literally thousands of cops were protesting outside Yankee Stadium, drinking beer and holding up protest signs, there were gangs of teenagers mugging people and breaking into cars. If one takes a longer view, I think that something like this that allowed for the emergence of a Giuliani who could really take a much tougher position on crime, and in a sense, in doing so, sort of rescue the police department.

Gotham Gazette: But do you think you can really draw a straight line between the riots after the blackout in 1977 and Giuliani?

Jonathan Mahler: No, not a straight line. But I think you can see that in a sense the city had to bottom out in a way for the people to be willing to endure the things that Giuliani did. They would have been unthinkable in an earlier era, but once the city had been this low, it changed people's perspectives.

Calvin Johnson: How did you weave a narrative together out of all these events? Who did you talk to, and how did you piece together the story that you tell in the book?

Jonathan Mahler: Specifically the blackout?

Calvin Johnson Yes, Part Two of the book.

Jonathan Mahler: Different parts of the section I relied on different sources.

Before I get to Bushwick, I do a pretty lengthy retelling of how New York lost power from inside the control room of Con Edison. I did that largely through the telephone transcripts of the various Con Ed system operators, which were all subpoenaed for a federal investigation and have therefore been made available. I didn't even know they existed, frankly, and then I went down the Municipal Archives to see what they had. It was kind of a great find; it's incredibly dramatic reading. The system operator of Con Edison, William Jurith, you really see him panic. Here's this guy who is at the helm when New York City is about to lose power. So I used those telephone transcripts largely to figure out what had happened. One of the experts who was subpoenaed in the federal investigation to analyze what had gone wrong was very helpful in explaining all the science I had to understand. There were three separate investigations - a city, federal, and state investigation - and I read all of those. There was also all the newspaper coverage at the time, but because of the looting, what had actually gone wrong kind of got overshadowed.

In terms of what happened in Bushwick, I started by meeting one cop who had worked in Bushwick that night. As luck would have it, they were having a precinct reunion in a couple of months. I went with him to the precinct reunion in Nassau County and there were dozens of cops there who had worked that night. They were all great, and shared their memories with me. Then I followed up with a lot of them and went back to the neighborhood with them.

I also got all the police reports. First I tried to get the police reports from the city. If you ever try to get a police report from 2004, they're going to think you're crazy; asking for one from 1977 was a joke. After the blackout the Ford Foundation had done a study - it was called Blackout Looting - and I went to the guys who had done this study and they had everything. So I used those against the accounts of the cops against any newspaper reports, and then I met some people who were living in Bushwick that night.

Barbara Oliver: You write in the book that WINS at first reported that it was a party atmosphere in the city. How long did it take it before the radio stations began to realize that it was not a party everywhere?

Jonathan Mahler: I'm not sure exactly when, but my impression is that it was well after midnight. And the looted had really started right away.

Marsha Cohen: I actually worked at Channel 2 News in 1977, and I was in the newsroom that night. We didn't know anything was happening until people's friends started calling, and their mother-in-laws started calling saying, "It's getting very dark in our apartment. What's going on out there?" That was the first we heard of the blackout.

The minute we started to send the crews out - they were just starting to get videotape where they could go out and microwave and get stuff happening live - we knew, because they were coming back from outside in the trucks, and telling us how bad things were. We broadcast all over the country that night, only New York couldn't see it. We knew pretty soon because the reporters and the cameramen were coming back with the footage showing us what was going on by 10 or 11 o'clock -- that the city was under siege.

NEW YORK AND THE REST OF THE COUNTRY AFTER THE BLACKOUT

Gotham Gazette: You also mention in the book Jimmy Carter, who New York City helped to elect and who swore at the beginning of his term never to tell the city "drop dead." Actually, by some interpretation, he did just that by refusing to allow federal disaster funds to go to New York after the blackout. Did the blackout serve as a turning point for the way the rest of the country saw New York?

Jonathan Mahler: I don't know that it was a turning point so much as an affirmation, or a reaffirmation. The rest of the country was already very down on New York. It was not a safe place to visit; it was dirty. Throughout this whole summer, the superstar of the New York Yankees - Reggie Jackson - and its manager - Billy Martin - were in a nasty public dispute that didn't reflect well on New York. So I think that actually one of the editorials that I read from some other city was basically to the effect that New York got what it deserved; who would have expected anything else to happen in New York after the lights went out? That was very much the national view: Of course when the lights went out in New York the criminals ran wild, it's New York.

As far as Carter goes, it wasn't only that Carter failed to make the emergency funds available to the city, which the city badly needed - there were hundreds of millions of funds in damages. He didn't even visit New York in the wake of the blackout, even though Vernon Jordan, who was at the time the head of the National Urban League, tried to push him to. He eventually came in October, but he didn't come after New York had endured a major tragedy.

It was also just a time when the city's poorer neighborhoods were in trouble. In the ensuing years we've all seen the symbolic power of politicians going to poor neighborhoods. The South Bronx, for years, became a mandatory stop for national politicians. Carter did, to his credit, come in October. But he should have come right after the blackout.

Gotham Gazette: Besides Carter not coming to New York or providing aid directly after the blackout, are there policies you can point to on the federal level that indicated the f government was no longer focusing on New York, or cities in general?

Jonathan Mahler: One of the things that Carter had run on and that was attractive to New York was that the federal government was going to relieve some of the welfare costs for the cities. It's something that he never followed through on, and this was at a time that New York was on the verge of bankruptcy and there was massive unemployment.

Naomi Dagen Bloom: What I am interested in is whether you had a sense that in 1977 things were going well for other cities. [They probably thought it was] kind of nice to have New York look so bad.

Jonathan Mahler: I think that's a good question. I haven't studied other cities in depth during that era, but I think it wasn't a great time for American cities. What other cities like Detroit and Newark experienced in the 1960s, New York kind of held off, in part because of Mayor John Lindsay. For all his flaws, he handled those tense moments after the Martin Luther King Jr. assassination very well. So I think the city avoided those racially driven riots in the 1960s. In some ways, that bottled up and suppressed rage came out during the blackout.

I also think that New York was a more ambitious city in some ways. No American city has tried to do so much for its citizens - and did so much for its citizens as New York did, under Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia most notably. Here was somebody who drove around every Sunday looking for things to build. What a different era! Because of that fact, New York had farther to fall in a way; the New York idea was such a lofty one.

THEN AND NOW: THE BLACKOUT OF 2003

Gotham Gazette: You started writing this book in 2000. So at some point you were researching the 1977 blackout, and then the 2003 blackout happened. What were your thoughts at that time?

Jonathan Mahler: Before that, I was researching the blackout on September 11, 2001. Obviously, those are two very different events, but it did strike me how much the public perception of New York had changed. After the blackout in 1977, everyone was saying that New York got what it deserved, and then there was just this tremendous outpouring of sympathy and support for New York after September 11.

In terms of the 2003 blackout, I live in Brooklyn, and I drove around Brooklyn that night because I was curious what would happen. As you know, there was no looting, nothing. I think there are circumstantial factors. When the lights went out in 1977, it was already dark; when we lost power in 2003 it was late in the afternoon but it was still light out. I think that's certainly a factor, but I think the aftermath of the 2003 blackout is a testament to the fact that the city is a much different place.

One way that we can hone in to this idea is that there was no looting in Bushwick. I talked to a couple of people afterward just because I was interested in knowing why. It is my sense that what the city has done mostly through partly private-public partnerships since this era is help people own their own houses. Bushwick has built quite a bit of low-income housing that people have bought. When you have a community of homeowners, obviously the chances of this happening are greatly diminished.

Ron Bloom: Just to give you some context, I was working that summer two years ago in Harlem Hospital in the psych ward when the lights went out. I finally found a door I could escape from at 5 o'clock, and I live in Harlem, so I literally walked home from 135th and Lennox to 124th and Amsterdam. I was comfortable; it was a completely different kind of place [than what was described in 1977].

Jonathan Mahler: Were you here in 1977?

Ron Bloom: No, I was outside the city. But I was here in 1965, and that was a party.

Jonathan Mahler: 1965 and 2003 were similar; 1977 was the exception.

DID NEW YORK "DESERVE IT"?

Mike Miscione: Can't a credible case be made that New York did get what it deserved?

Jonathan Mahler: How would that case be made?

Mike Miscione: Well, since the Wagner administration, the finances of New York had basically been a house of cards meant to prop up the various administrations of the city, leading eventually to the financial collapse of the city. This collapse made the city unprepared for an emergency like this. Concurrently, that system was meant to prop up a social welfare system that essentially inflamed the elements that led to the rioting. There was a tremendous hubris about New York City toward the rest of the country that I think that the rest of the country perceived - accurately so.

Jonathan Mahler: That's of course the debate that followed the blackout: Was this a form of social protest, was this a cry for help from the ghetto, or was this just criminals running wild? That became the dialogue afterward.

Certainly New York was not on a sustainable course. That much was clear well before 1977. The moment that Abraham Beame took office he knew he was inheriting a mess; as comptroller of the city before he knew better than anyone. Whether or not the city deserved to be turned upside down in a night of rioting and destruction is, maybe, a separate question. But certainly it wasn't working financially.

THE REBIRTH OF NEW YORK

Even as the city struggled, places like dance club Studio 54 were thriving |

Gotham Gazette: If we could turn away from the blackout for a minute, because the book isn't just about New York falling apart; it's about New York at a turning point. At one point you write that the city is "blooming in decay." Can you talk a little bit about the signs of rebirth or change that New York was starting to show in 1977?

Jonathan Mahler: Before I go on to that specific question, just to pick up on your point, it was spontaneously regenerating and re-imagining itself. I was only eight years old in 1977. And just writing this book made me wish that I were old enough to be living in the city then. As bad as it seemed in many ways, there were so many exciting things going on. It was a great cultural moment: the whole disco scene was flourishing, the whole punk rock movement was happening, and it just seemed like the city was this wild, exciting place.

In terms of the specifics of your question, I think the best example of it is SoHo, a neighborhood that had once been filled with factory workers and bustling activity. But over the course of the 1960s and early 1970s, it had been abandoned and these old lofts were left empty. And then gradually this community of artists started moving in and repurposing these wide open spaces that had once been long tables for garment workers - turning them into lofts and studios for their work. Then of course the art dealers followed, and then the boutique storeowners followed, and then the restaurants followed. Dean and Deluca opened in SoHo in September 1977. And, voila, you have today's SoHo. It's a good example of how the city finds a way to survive, to reinvent itself to re-imagine itself and to adapt, in a sense. That's my favorite example.

THE 1977 MAYORAL CAMPAIGN

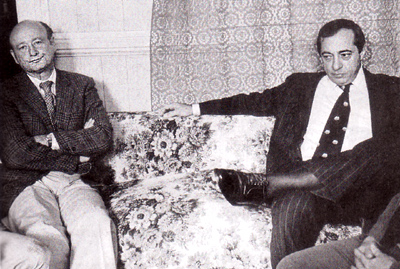

Ed Koch (left) and Mario Cuomo (right) engaged in a nasty campaign for mayor |

Gotham Gazette: During the mayoral election of 1977, how much did the victory of Ed Koch, the insurgent candidate who didn't seem to have a chance at first, rely on the fact that he was imagining a so-called new New York, and how much of it relied on the fact that he played into what you refer to as "blackout backlash," which was a racist backlash largely coming from the outer boroughs?

Jonathan Mahler: I think it was the latter; I don't think anyone has ever accused Ed Koch of being a visionary. I don't even think he would claim to be one. He sounded tough, and he said he would stand up to the unions who had been holding New York hostage; he campaigned for the death penalty; he said he was going to be tough on crime. And it was a very practical message. I don't mean to disparage Koch too much, because I think he came to serve as a great mascot for the city and came to lift the city's spirits in a really important way.

I think a lot of [Koch's victory] was due to his campaign manager, David Garth. Without him, Koch wouldn't have won. And the truth is that Cuomo ran a terrible campaign and kind of destructed.

Someone like Bella Abzug was too far left to be elected in this climate. It was already clear when Abzug was promising the city that she wasn't going to close fire stations, that she was going to eliminate the tuition that had recently been imposed in City College, that she was going to beef up the municipal hospital system, that she was going to add childcare centers and senior centers and libraries - that it was impractical. It was unrealistic, and it was out of touch with where the city was in that moment.

Gotham Gazette: One thing that struck me was - as we start this year's mayoral campaign - you had Bella Abzug driving around in the Impala with a bullhorn. You had people throwing sausage pizzas at Ed Koch's car in Brooklyn. It just all seemed much more colorful than what we get today. Do you feel like there's a different way that politics and campaigning works in New York City now than it did back then?

Jonathan Mahler: I don't cover New York City politics now. But certainly, the characters to me, anyway, were just much larger than the prospect of Bloomberg and Freddie Ferrer, or whoever it is. Whereas Bella Abzug and Mario Cuomo and Ed Koch, those were personalities.

In terms of campaigning, I do think that politicians seemed to work the outer boroughs more than they do now, or at least they work them in a different way. Just reading the papers from that summer, I was really struck by, for instance, this photo of Mario Cuomo campaigning at a beach club in Brighton Beach and surrounded by all these Jewish guys in their swimming trucks. I just can't imagine Bloomberg doing that today. But I don't really know why that is. I guess because of TV advertising. There was obviously television advertising in this campaign, but no one really had enough money to do as much TV advertising as they wanted to, so they had to just get out on the streets.

And, I think you had a somewhat unique situation here where you had Cuomo and Koch. Cuomo, from the moment he entered the race, was considered a real contender because those who did know him knew how eloquent and wonderful he was; and Governor Hugh Carey pushed him to run, which was going to be helpful to him. So the two of them certainly had to get out a lot more, because no one knew who they were.

BASEBALL AS A METAPHOR FOR NEW YORK CITY

Muriel Mandell: It's interesting that no one has talked at all about the many chapters you had on baseball and Reggie [Jackson] and Billy [Martin].

Jonathan Mahler: I guess I can talk about that as well. For those who haven't read this book, baseball is a main storyline as well. It was the year that Reggie Jackson arrived in New York amid a great amount of fanfare after baseball had its first free agent draft. From the moment he arrived - even before he arrived - he was at loggerheads with the team's manager, Billy Martin.

The feud between the two of them was played out to no end in the tabloids this summer. Keep in mind that Rupert Murdoch had just bought the New York Post at the end of 1976, moved into the editor's office on January 1, 1977, and started turning it into the New York Post we know today. It is a far cry from the New York Post that it was before, which was a great old liberal newspaper. Reggie and Billy fought this incredibly nasty feud in the tabloids, with the sorts of quotes that you would never see today.

The city became very invested in the struggle between these two people. This plays into the larger theme of my book, but before I say this, let me say that I am not one who tries to get too metaphorical about sports, so forgive me if this seems like too much of a stretch. In many ways, the sort of old New York/new New York struggle that was going on in so many other senses in the city was very similar to the one that was going on between Reggie Jackson and Billy Martin. You had this arrogant superstar, who was black, making millions of dollars. Then you had Billy Martin, who had played for the Yankees in the 1950s, who was real scrappy, tough, from a hardscrabble childhood - he was really a working class icon for New York. So much of the city naturally sided with Billy Martin in this dispute.

That feud also plays itself out over the course of the summer and while this will be sort of ruining the book for those of you who haven't read it, the book climaxes with Reggie hitting three home runs in a single World-series game which redeemed him. And, in a symbolic sense, it can be seen as a sort of redemption from New York. The tabloids certainly read it that way: the Post in the day after the three home runs had an editorial that says "who dares call New York a lost cause?"

Kristy Bristen: I actually read the book because of the Yankee connection. When I was reading the book, I thought the whole thing was fascinating, but I kept thinking a lot about things that have changed since 1977 and things that haven't. When I was reading the book, it was a few weeks ago when George Steinbrenner sent his memo to the team basically threatening that heads are going to roll. I'm wondering if you had a chance to talk to George Steinbrenner; is he one of the people you interviewed? It's interesting, out of all these people he's still around.

Jonathan Mahler: I didn't talk to him. I talked to Reggie Jackson and I talked to a lot of the other players on the team. I made an initial attempt to interview him, but I felt like it was going to require more time than I wanted to devote to it; I just felt like I wasn't going to learn anything new.

In many ways I feel like he's sort of the exception to the rule that players and managers aren't as colorful as they were then and they don't say the kinds of provocative things they used to say. He still does it. He's almost become a caricature of himself - he has become a caricature of himself.

He was relatively new to New York in 1977 and the city really turned on him. I think now Yankee fans would tolerate him much more than they did then, because he's now built some winning teams. Then, people really hated him. Part of it was that he was giving Billy Martin such a hard time and people felt so loyal and passionate about Billy Martin so they couldn't abide him: "Here he was some shipbuilder from Cleveland who comes into New York and who does he think he is?" I can't stand him myself, so the sooner he goes, the better. He makes it hard to root for the Yankees.

Katie Store: I have no problem hating the Yankees; I detest them because I am from Pittsburgh, which has a really small market team. I think this "baseball and urban life in New York" metaphor is a really interesting one because the way that Steinbrenner handled free agency by just loading money onto Reggie Jackson has bred a whole different baseball than the one that used to be. And, similarly the way that I think New York recuperated from this period of decay bred a whole different kind of urban life. What I'm wondering is - this is outside the scope of the book, but this is what came into my head and what troubled me reading this - is the plight of the ordinary person better or worse now? Was the way we handled it really good? And, was the plight of the small-market team any better now than it was before, because clearly it's not.

Jonathan Mahler: I think that's a very good point, and it has come up in my readings before. I think there's something missing from New York now and as one who's not part of the power elite of New York myself, it's a hard place to live, it's expensive. I think basically what you're saying is correct. Money and power are concentrated now among a small group of the rich and powerful, the elite group. The same is true in baseball as in the city. Rupert Murdoch is one, for example: He was just starting out in 1977 and now he's one of the richest men in New York and he has an incredible amount of power. I don't know how there is going to be a middle class in New York at this rate in ten years. It just seems very difficult.

Mike Miscione: But New York was a pretty miserable place for a lot of people.

Jonathan Mahler: I'm not nostalgic for New York of 1977. I think that the transition that occurred in this era that I'm writing about is when New York went from being a kind of working class city to being the city it is today.

I think that what New York had at that time was doing was unique. The New York experiment was unlike what was happening in other American cities: the municipal hospitals, the subsidized subways, the rent-controlled apartments, public housing, free high quality public education. You weren't getting that in other cities.

Ron Bloom: The 1960s, when we lived here, was rent-controlled apartments and the streets felt safe. We left for 30 years and lived in Baltimore. We started coming back, and I remember reading The Bonfire of the Vanities, especially the beginning of it, and really getting frightened. And I would see these abandoned cars when we came to visit family here, walking the streets, seeing the cars that said "No radio inside." Things have changed. I know it's not in certain ways for the best, but it has changed. My wife Naomi [Bloom] has spoken about the fact that this has become a buyer's apartment place rather than a renter's place.

Jonathan Mahler: You can't make the argument "would I rather raise my family in New York of 1977 or New York City today?" Of course I'd rather raise a family today; it is a cleaner, safer, better place to live. That doesn't mean that we can't be sad about some things that are no longer part of the city. It's not a zero-sum game; it's not a one-to-one equation. I think there was better music, for instance. It would have been more fun to be a teenager then.

Gotham Gazette: Is there is anything besides the music of 1977 that we should lament not having now?

Jonathan Mahler: I think that before 1977, before the late 1960s and early 1970s, New York was a much more hospitable place for the working class; it was an easier place to live and raise your children. So yes.

Is Public Art For The Public

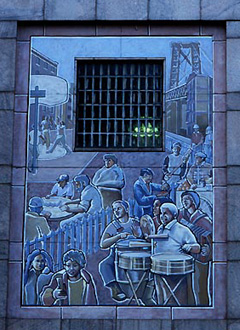

Richard Haas White St. Detention Center |

Several years after Richard Haas painted an epic mural about a century of immigration to the Lower East Side, the artist was confronted by a group called the Down With The Mural Committee. They objected to one of the seven panels, which depicted a modern-day vendor at the center of some familiar if unflattering street life -- a bodega with its steel gate down, a sleeping vagrant, some stray dogs, a woman in a halter-top. These images, painted in 1989, were insulting to the community, the protesters said.

Haas, a well-established artist who has received commissions throughout the city and the country, was taken aback. Nevertheless, he agreed to replace his work with a completely new scene – no more woman in a halter top; now there are two children on their way to school. Gone are the bodega, the dogs and the vagrant; now there are basketball players, a baseball player, construction workers, even a Tito Puente-like band.

“I was surprised by the protest," Haas was quoted as saying in 1992. "But working in the public arena today is like stepping into a mine field."

The story of Haas’ mural is told briefly in “City Art,” which is both a current exhibition at the Center for Architecture and a newly published book about New York City’s Percent For Art program. His is far from the most controversial commission in the 22-year-old history of the program, though it may be among the unluckiest.

Elizabeth Turk Manhole Cover Seguine Avenue, Staten Island Launch slideshow for more images |

The law that created the Percent for Art program in 1983 (some 25 years after the first such program began in Philadelphia) requires that one percent (more or less) of the budget for every city-funded construction project be used for public artworks. Since then, more than $26 million has been spent on some 200 works of art in locations throughout the five boroughs. Because the last two decades have seen a boom in school construction, the art is mostly in schools. But some of it is in courthouses, firehouses, and libraries, and a few pieces are in far less traditional venues: Sculptor Elizabeth Turk designed 87 manhole covers for Seguine Avenue on Staten Island; Milo Mottola created a life-size, totally operable “Totally Kid Carousel” atop the sewage treatment plant in Harlem

Haas’ mural is on the wall of a jail. This would be bad enough, but the jail is the notorious Tombs, now in its third building and officially known as the White Street Detention Center. (The person who launched the protest was a newly transferred deputy warden, who was an official of the Department of Correction Officers Hispanic Society.) Even worse, the complex in which the prison is located is named after Bernard Kerik.

But what may be worst of all is that, most of the year, the mural is virtually invisible, completely obscured by the leaves of the trees that line White Street – and too high up for eye-level viewing in any case.

This is not mentioned in the book or the exhibition, or on the Web site of the Department of Cultural Affairs, which administers the Percent for Art program. Just walk down to White Street near Baxter, and see (or, actually, don't see) for yourself.

The mural’s literal obscurity, and the controversy in its past, prompt a few questions: What is public art, and who (and what) is it for? Is public art for the public? And who, exactly, make up the public? Does public art have to be educational? Must it reflect the values of a democratic society and those of the community in which it is located, or can it challenge those values? Can it depict a community's reality -- the way things are, no matter how unfortunate -- or must it reflect a community's aspirations -- the way things could be? Or should it simply insert a bit of pleasure into the busy lives of passers-by?

These are precisely the questions that the contributors to “City Art” pose. (The last question is from the book’s essay by art critic Eleanor Heartney.) The exhibition, as its introductory wall text puts it, "invites viewers to consider the role public art plays in our daily lives and communities, and in shaping our identity as New Yorkers.”

Alice Aycock Project for the 107th Police Precinct, Queens, 1992. Community members were at first alarmed. |

It is easy to overlook this daily role, since for most people, art becomes public only when there is hoopla -- such as the two-week spectacle of The Gates Project in Central Park -- or when there is heat: The controversies connected to public art pale beside the ruckus kicked up over “indecent art”, but Percent for Art projects have had their share:

- Education officials requested the alteration of some of the porcelain figures of students that Ann Agree had created for the lobby of Intermediate School 137 in Queens, removing “doo rags,” tank tops, religious ornaments and jewelry; they also asked her to include a figure in a wheelchair. As the exhibition explains, “Agee complied with some of the requests and eliminated certain figures that she wasn’t willing to alter.”

- Community residents were baffled by the structure Alice Aycock created for the top of the 107th precinct in Queens. It resembles a satellite dish and, to the artist, was a symbol of the communication that police must have with the community. Some residents thought it was an actual dish however, and either suspected it was being used for surveillance or feared it would interfere with their television reception. Despite such worries, the sculpture remains in place.

- Residents of the South Bronx objected to the art commissioned for another police precinct, the 44th, which John Ahearn had based on life models made of actual if not thoroughly upstanding people from the neighborhood, one shirtless posed with a beat box, another in a hooded sweatshirt with his pit bull. The sculptor agreed to take the works down; they are now exhibited in Socrates Sculpture Park.

This last controversy was the subject of “Whose Art Is It?” by Jane Kramer, a celebrated 1993 piece in the New Yorker magazine that was turned into a book much talked about in the art world.

Such disagreements are sure to continue. This is why community feedback is built into the process; the local community boards are involved from the beginning. In the same neighborhood where Ahearn’s sculptures were commissioned, a work in progress by Cai Guo-Qiang outside the new criminal courthouse inspired community objection because it looked like a huge granite chain -- reminiscent, some said, of a chain gang, and thus inappropriate for the courthouse. The artist changed his sculpture, as community board 4 district manager Margarita Hunt-Tejada explains, to look more like “interlocking cubes instead of chain links.” Clearly, it takes a certain kind of artist to participate in public projects – one who is as comfortable with politics as with paint.

But the new public art -- not just from the Percent for Art program, but from the Arts for Transit program in the subway as well -- could never be mistaken for the public art of the past, those rusted-green military generals. True, some of the art is still meant to inspire awe in heroes, though the heroes have changed: A new mural by Daniel Galvez entitled “Homage to Malcolm X”, which includes a reprint of the “Whatever Means Necessary” speech, will be one of the three Percent for Art works incorporated into the newly renovated Audubon Ballroom, reopening this month.

Launch slideshow for more images |

But all those whimsical and intriguing mosaics in the subway stations, all the imagination that pokes out from the corner of your eye throughout the city (see slideshow) -- the pieces created over the past two decades surely do what Picasso once said art can do: “Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life,” an impressive feat in a place as full of dirt as New York.

Urban Conversations: U.S. Mayors and Innovative Leadership

At a recent New School University forum entitled, “Urban Conversations: U.S. Mayors and Innovative Leadership,” three mayors – Tom Murphy of Pittsburgh, Kay Barnes of Kansas City, and Gavin Newsome of San Francisco - talked about how they had handled stadium issues in their cities. The panel was moderated by George Stephanopoulous. The following is an edited transcript of the discussion.

George Stephanopoulos:Let me ask about something New York is going through right now, the huge controversy of whether to build a new football stadium on the West side. Mayor Tom Murphy of Pittsburgh, you succeeded after losing a referendum and then pushing it through the state legislature, is that correct?

Mayor Tom Murphy, Pittsburgh:We sort of said we’re going to do it anyway.

George Stephanopoulos:And you [Mayor Kay Barnes of Kansas City], that’s where you were successful. You brought in arenas but not a new baseball stadium. Talk about the experience and what the difficulty was in getting public support for it.

Mayor Kay Barnes, Kansas City:We had an interesting experience in Kansas City with our arena issue; it was not doing well in the polling early on. [But then] we received a call from the leadership of Enterprise Car Company, which has its corporate base in St. Louis: Under no circumstance would they support what we had put on the ballot, which was an increase in rental car fees and hotel fees to fund the public portion of the arena. They said to us, "we’re going to go after you. We will spend whatever it takes to fight you in this campaign." And the more they spent, the more it helped us. Because it created this situation where they were the enemy, and we played up the St. Louis part, because there’s always this competition within Missouri between St. Louis and Kansas City. They ended up spending over one million dollars against us in the campaign and we won by 61 percent, thanks to Enterprise. So it was an interesting political experience to see the value of an identified enemy and then really making that the focal point of the campaign. We learned a lot in that experience and we’re all very excited about what the arena will mean in terms of our downtown revitalization.

Mayor Tom Murphy, Pittsburgh:Let me just say that I was caught between belief and reality on this. I fundamentally don’t believe that the public ought to be investing in ballparks. That said, we have built a new football stadium, a new baseball park and a convention center, and we spent $1 billion doing so. We did that because that’s the reality of life; that’s the market place. For a city like Pittsburgh or Kansas City, small markets competing with George Steinbrenner, who’s spending $200 million on [players for] a team when we spend $20 million on a team. So it was a question to us of losing the teams, and it's hard to imagine a Pittsburgh without the Pittsburgh Steelers or the Pittsburgh Pirates, after having lost the steel industry. So the reality was [we had] to put a deal together. We went out to the public, had a referendum, 70 percent of the people voted against the referendum saying, "we don’t want to use public money." Two months later, I said, "we’re building them anyhow," and figured out a way to put the money together. That’s not how you gain popularity with the electorate.

George Stephanopoulos:And once you’ve done it though how is it?

Mayor Tom Murphy, Pittsburgh:There are still people who are upset about it.

Mayor Gavin Newsom, San Francisco:Well, with respect, eat your heart out because we built a baseball stadium without any public subsidy: PacBell Park. And it’s an extraordinary stadium even if it’s not the number one stadium. Every mayor’s going to sit here and say, â€Football stadiums are a great economic stimulus.’ I think one of the great experts is your colleague, George Will, on this, who has made it crystal clear to me; he said, "You Mr. Mayor will be saying that, but you will be wrong when you do." Well I don’t want to prove George right on anything. So I’m not going to say it. The fact is football stadiums are not a great economic stimulus, they are just not great for the economy. It’s a sort of myth.

With baseball stadiums, however, you can make a very different argument and [a good example of] that argument, I think, is PacBell Park -- now called SBC Park. It’s just an extraordinary city that’s being built: 6,000 housing units around this area; a fixed light rail system; University of California San Francisco, which is our institution of higher learning where biotech and life science and nanotech really were conceived.

Our 49ers stadium, though, we’re in the midst of that discussion and we passed an initiative that allowed for $100 million – barely passed – in revenue bonds. So it’s not a general obligation bond, it’s got to be paid back with some revenue component. It’s a way of subsidizing, modestly, the construction, but not a way of ultimately giving away a city subsidy, except in a bond capacity.

George Stephanopoulos:Is the basic critical problem you all face here when you’re trying to get the financing that the voters say, â€listen we’re going to be paying for overpaid players and greedy owners’?

Mayor Tom Murphy, Pittsburgh:Well you get two messages from the voters: Don’t use public money for ball parks to pay for the greedy owners, but don’t you dare let these teams leave. So you’ve got a mixed message in the same breath; that’s part of the challenge of how you put together a plan and move forward.

George Stephanopoulos: And at the end of the day what pushes you to do it -- the fear of losing the team or the actual benefit of what having the stadium can bring?

Mayor Kay Barnes, Kansas City:I think it is fear of losing the team as much as anything. We get referred to all the time as small markets in major league baseball and football, and certainly that is true in many ways. But the reality is that it is a very important part of a city’s image, large or small. As cranky as the voters will get over that kind of subsidy, when push comes to shove, I think there is a recognition that it may well be worth the investment, not only to â€keep the team for psychological reasons,’ but also for economic development reasons. The baseball stadium is an excellent example of that in almost any community. That’s why we see almost all that are being built, at this point, being built in a downtown, or very near a downtown area, simply because it is an economic development stimulus.

Mayor Gavin Newsom, San Francisco:And what we’re seeing with football stadiums – and this is our discussion of the 49ers – is that you want to anchor them in mixed-use development. You want to create a component where you’ve got housing, perhaps hotels, you’ve got retail components, so it’s all packaged together, so you can legitimately make that argument. But a stand-alone stadium, with just a few games a year, you’re not gonna make an [effective] argument. For example, our number one issue in San Francisco is homelessness. If I’m going to say that I’m going to subsidize a multi-billionaire by getting him over $100 million in subsidies, but I can’t help people out there in the streets dually diagnosed with drug and alcohol addictions and bi-polar disorder, boy I’ve really made a difficult decision on the basis of my morality and judgment.

Mayor Tom Murphy, Pittsburgh: The economics of it are really that arenas make the most sense. They are used 250 times, so they generate a lot of activity. Baseball is next. Football, it’s hard to justify a football stadium on economic development purposes for 14 weeks, 12 games a year. Â

Hockey and Basketball Arena

HOCKEY AND BASKETBALL ARENAS

| Location: |

Brooklyn, New York

|

Vancouver, British Columbia | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Denver, Colorado |

| Date: | 2006 (Projected) | Opened September 1995 | 1996 | Opened 1999 |

| Uses: | Nets basketball games, concerts, other events. | Professional basketball, hockey, and lacrosse games, concerts, and 2010 Olympics. | Professional basketball and hockey games, concerts, circuses, 2002 NBA All-Star Game, and other events. | Pepsi Center hosts professional basketball, hockey, lacrosse, and arena football games, concerts and other events. |

| Size: | Seats 20,000 | Seats 20,004 | Seats 21,600 people | Seats 19,000 people |

| Projected Cost: | $435 million (projected) | $160 million (Canadian) | $206 million | $160 million |

| Public Cost: | $150 million in government funds for streets and rail connections. | $13 million from the city and state. | $4.5 million in infrastructure, $2.25 million for construction sales tax rebates and $2.1 million annually for property tax exemptions. | |

| Private Financing: | Nets owner Bruce Ratner plans to pay for the arena, the centerpiece of a $2.5 billion commercial and residential development that would stretch for three blocks along Atlantic Avenue. | Primarily privately financed by General Motors Canada, which paid $18.5 million for 20-year naming rights. | $200 million, which includes naming rights at $40 million over 21 years and an undisclosed additional cost eight years afterward. | Privately financed by investors and through the sale of luxury boxes. Pepsi paid an estimated $68 million for naming rights. |

| Voter Referendum? | No | No | No | No |

| At Issue: | Opponents say as many as 1,000 people will be evicted from their homes. They also say that the majority of the new housing will not be affordable to current residents and fear an influx of traffic. The project will use Tax Increment Financing, which diverts future property, sales and income taxes in a designated district until the developer can pay off the costs of the project. | While the General Motors Place arena will host the hockey games for the 2010 Winter Olympic Games, government officials are committing $400 million to build other venues for other events. | In Philadelphia, all the major sports teams – football, baseball, basketball, and hockey – wanted new venues. The new arena was the first built and opened in 1996. Though the teams wanted a larger public subsidy, the owners had to pay for most of it privately. The old arena, The Spectrum, is still open and used for concerts, minor league hockey games, and other events. Philadelphia has recently built a new football stadium for the Eagles and a new baseball stadium for the Phillies, both with public subsidies. | In 1986, Denver’s McNichols Arena was renovated at a cost of $12.5 million to the city, but owners of basketball and hockey teams wanted a new one. In return for breaking the lease on the old building, the city wanted the teams to agree to stay in Denver for 25 years. The teams resisted. Two years later an agreement was reached. With new stadiums for baseball and football that used public subsidies and tax increases also planned, owners were forced to finance it primarily with private money. |

| Benefits Promised: |

The arena, designed by architect Frank Gehry, will be a tourist attraction featuring a skating rink, restaurants, and stores. In addition to the arena, the Atlantic Yards plan calls for six acres of park land, 4,500 apartments, 2.1 million square feet of commercial office space, and 300,000 square feet of retail space to be built over a 10-year period. Officials promise to create 15,000 construction jobs, over 10,000 permanent jobs, and 400 permanent jobs at the arena. |

General Motors Place was built in 1995 to showcase professional sports, concerts and other events. | The new arena was designed to bring more high profile events to the area. | The Pepsi Center is part of an area dedicated to sports and recreation. It is located near a football stadium, baseball stadium, and Six Flags amusement park. |

| Benefits Delivered: | The Vancouver Grizzlies basketball team moved to Memphis in 2001. The lacrosse team folded. And in 2005, the arena did not host any games by the Canucks because the professional hockey season was suspended over contract disputes between owners and players. | In addition to sports, the arena has drawn other events such as the Republican National Convention in 2000. | The arena was recently voted the top basketball arena by USA Today. |

The Citizen

|

The Citizen has moved to a new location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

Is Broadband a Public Utility? A Right?

Few people in the city would argue that the subway system or the airports or even the water system were any more important to New York’s economy than the networks of telephones, cables, computers and other high-tech devices that insiders like to call the city’s telecommunications infrastructure. Yet telecommunications stands out from these other systems in at least three ways:

1. It is developed and operated almost entirely by private companies.

2. It is driven by technology that is constantly changing.

3. It is directed by policy set almost entirely at the state or federal level, not locally.

This is the conclusion of a new report by three city agencies, which offers ways to overcome the difficulties. “Telecommunications and Economic Development in New York City: A Plan For Action” (In PDF Format) aims to make the city’s telecommunications infrastructure more

- Reliable

- Accessible

- And up-to-date

"Although New York City residents and businesses have access to an array of high-speed telecommunications connections and services that no other city can match, there are specific parts of the city where access is limited, such as Hunts Point in the Bronx and Sunset Park, Brooklyn," said Mayor Michael Bloomberg. "If New York City is to maintain its role as a world center of finance, communications and culture, we have to extend access to broadband [high-speed Internet] communications to all, as well as continuously improve the reliability of our telecommunications networks and take advantage of emerging technologies."

Among the 21 initiatives the team recommends:

-using federal funds designated for rebuilding Lower Manhattan to improve the telecommunications infrastructure,

-using city-owned property to support the deployment of wireless technology,

-encouraging Business Improvement Districts and other local organizations to promote wireless technologies

-collaborating with universities to develop new technologies and business ventures, and

-developing education programs for small business owners.

The plan does not go as far as to say that the municipal government itself should become an owner of a broadband infrastructure. But it doesn’t say it shouldn’t.

Municipally-Owned Broadband?

The City Council’s Technology in Government Committee, in addition to holding hearings to get public comments on the report, has also introduced legislation to create a task force on how broadband can be made available to all New Yorkers.

“Ensuring the availability of affordable broadband is about more than providing access to essential Internet tools like job resources, online banking and continued job training and education,” says Councilmember Gale Brewer, chair of the committee. “It is obvious that within the next several years those that do not have access to the new generation of broadband-driven communications technologies, such as Internet telephony (VOIP), telemedicine and telecommuting will be at a distinct disadvantage. We need to ensure that the city has the infrastructure to provide our small businesses, non-profits and low-income residents with the tools they will need to compete and flourish.”

The United States currently ranks 13th in the world in terms of the percentage of its citizens who have broadband. As a result, a number of local governments have started to take a closer look at telecommunications in their own cities. However, there is considerable disagreement over whether or nor broadband should be viewed as a public utility – like water, gas or electricity -- that municipal governments have the right to provide the infrastructure for.

According to standard economic logic, governments should only step in to provide services when there has been a “market failure,” or when the private sector has failed to provide a service competitively. In the case of broadband, many experts argue that there has been a market failure for a number of reasons. These include the fact that the United States has lagged in the penetration of broadband services, the cost of broadband is much higher than in other countries, there is little choice between broadband providers – typically, the phone company and the cable TV company – and, therefore, some areas still lack any affordable choices for high-speed Internet. Others disagree, saying that the market will eventually serve everyone at rates they can afford, thereby closing the gap that some call the digital divide.

In addition to the economic logic of market failure, there is a growing belief in the area of social justice activism that communications should be viewed as a right, similar to the right for food, shelter, clothing and well-being that are considered universal human rights. Whichever logic one uses, the fact is that municipal governments from Philadelphia to Chicago to San Francisco are treating broadband as a basic public utility that they have the responsibility to provide the infrastructure for.

According to a Free Press report (in pdf format), “The telecom and cable kings of the broadband industry have failed to bridge the digital divide and opted to serve the most lucrative markets at the expense of universal, affordable access. As a result, local governments and community groups across the country have started building their own broadband networks, sometimes in a purely public service and more often through public-private partnerships.”

However, currently, ten states – including Pennsylvania, Michigan, Minnesota, Washington and Utah -- have legislation barring municipal governments from providing telecommunications services. Thirteen more – including Texas, Ohio, Colorado, Florida and Illinois -- are considering such anti-municipal broadband legislation, versions of which are being promoted around the country by telecom industry lobbyists from Verizon, Qwest, Comcast, Bell South and SBC Communications.

It remains to be seen whether New York’s new broadband task force, if created, will recommend following the lead of cities such as Chicago and Philadelphia in ensuring that affordable broadband is available to all residents. If the public wants it, though, we better act quickly, before corporate lobbyists make their way to Albany.

Laura Forlano is a doctoral student studying communication technology policy at Columbia University.Â

Culture and Construction

Earlier this month, a sharp-eyed reporter for the New York Times noticed that the performing arts center planned for Ground Zero will be excluded from the $500 million fundraising campaign for the World Trade Center site memorial. Instead, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation told Robin Pogrebin of the Times that fundraising for the center will be part of a “second phase.” To architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable, it is clear what this “second phase” really means -- the performing arts center will probably never be built.

And thus, Huxtable wrote with obvious fury two weeks later in the Wall Street Journal, the news of the center’s exclusion was “the final betrayal” in what has been a continuing “downgrading and evisceration of the cultural components” of Daniel Libeskind’s original plan -- thanks to those who lack “the courage, or conviction, to demand that the arts be restored to their proper place as one of the city’s greatest strengths and a source of its spiritual continuity.”

Time will tell whether or not Huxtable overreacted, whether the performing arts center winds up being built at Ground Zero to house the Joyce Theater, for 23 years a staple of dance in New York, and the Signature Theater Company, which for 14 years has presented the works of a different playwright each season. But Huxtable’s suspicions are hardly novel. In New York City, there long has been a complicated relationship between the arts and urban development …between culture and construction.

“Boozy:” The Art Of Robert Moses

To say that arts institutions in the city are obsessed with real estate is only to state that they are New Yorkers. This may explain, for example, the theme of this spring’s fundraising dinner for ART/New York, the alliance of some 400 non-profit theaters in New York, which is selling tables for its “Party with A View” gala in June that are labeled “high rise” (for tables selling for $10,000), “skyscraper” ($15,000) and, the highest designation, “landmark” ($25,000).

But a precocious downtown theater company called Les Freres Corbusier goes even further, taking the construction of big projects in the city more or less as the subject of its anarchic new play, “Boozy.” More or less, because the audience has to get through a lot of silly stuff -- videos of rabbits dressed up as Mussolini and FDR; weird jokes about croissants and weirder conspiracy theories; shenanigans involving the Shah of Iran and Nazi propaganda minister Josef Goebbels -- in order to get to the point of the play’s subtitle: “The Life, Death and Subsequent Vilification of Le Corbusier and, More Importantly, Robert Moses.”

The play works best for an audience that is already well-versed in architecture and urban planning. “Boozy” is a (silly) nickname for Le Corbusier, the influential Swiss architect and city planner (real name: Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris) who came up with the concept of what he called “the radiant city,” high-rise towers in park-like settings. The design was most familiarly used in many American public housing projects, which are now largely viewed as complete failures. Robert Moses was New York’s master builder, who for half a century was responsible for the construction of nearly everything in the city, its parks and its apartments, its bridges and its beaches, its most famous monuments, such as the United Nations and Shea Stadium, and its most hated highways, such as the Cross Bronx Expressway. After the publication of Robert Caro’s biography of Moses, “The Power Broker,” in 1974, Moses has been seen mostly in a negative light, as the man who bulldozed the neighborhoods of New York.

It would not be precisely accurate to say that the play aims to resurrect the reputations of these two men -- the clowning-around creates too much of a muddle for that -- but there are several exchanges that get at the ongoing debates in urban planning. One example:

“If we concede that great works must be built,” one character asks, “doesn’t it make sense that [they] spring from a single vision so that none are at cross-purposes?”

“If a Great Planner is guiding every decision,” replies Jane Jacobs (a character named after one-time Moses adversary and author of “The Death and Life of American Cities”), “then what is to prevent him – or a cabal of urban planners -- from using their money and power to further their own interests?”

“Corruption is a risk we take, but what is the alternative?” the first character counters. “Ideas by committee and the tyranny of an uneducated majority destroying every innovative idea because it is new and different?”

“This is a democracy,” Jane Jacobs responds. “People like Mr. Moses should listen to the voices of the people.”

It is a debate that animates the reconstruction of Ground Zero, but has other vivid examples as well, such as the case of Tilted Arc, a sculpture by Richard Serra. The curved wall of raw steel was installed in 1981 at Federal Plaza, near City Hall, and then removed in 1989 after area workers complained about it. In a democracy, which value was more important, the right of the artist to express himself freely, or the right of the workers to have the plaza they preferred?

“Boozy” fails to mention the effect of urban planning on the arts themselves, omitting the two arts-related incidents for which Robert Moses is best known. Moses fought to exclude Joseph Papp’s Shakespeare Festival from Central Park, one of the first fights he lost. Moses was also the person most responsible for creating Lincoln Center. He did so, not as a way to improve the arts, but as a way to revitalize a run-down neighborhood. The neighborhood, once the true-life setting for the musical “West Side Story,” certainly changed. What is less clear to many critics is what Lincoln Center has done for the arts itself – whether “the idea of a cultural campus set apart from the city” ever did much for the art housed there.

Lincoln Center was the first such campus to demonstrate the power of culture as urban renewal, and it has been imitated by cities across the nation, to varying effect. But cultural critics are quick to point out that the most successful such projects are those that have put existing older buildings to use as galleries, museums and performance spaces, allowing the community (artists, patrons, businesses, residents) to help shape the results.

Whether or not Les Freres Corbusier would argue for the greater benefits of Lincoln Center’s kind of “top-down” planning, their own example is instructive: After a successful run in the smaller Ohio Theater, “Boozy” is reopening May 1st at The 45 Bleecker Theater, a 199-seat theater that, as its proprietors (The Culture Project) proudly point out, was converted from a lumberyard less than a decade ago -- one of many such vibrant makeshift art spaces in the city.

Fresh Kills And High Line At MOMA: Construction As Reconstruction

Coincidentally or not, there are two separate exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art both describing ambitious construction projects in New York City that share some unusual traits; neither are likely to have interested Robert Moses.

On the third floor of the museum, there is an exhibition of the proposed design for the High Line, the long-defunct elevated railroad that runs for 22 blocks along the West Side of Manhattan from Greenwich Village to 34th Street. Included are sketches and models of what the designers have in mind for the site, a series of gardens and walkways that the curator has given such irritating names as “vegetal balcony.”

On the sixth floor, there is an exhibition on the redesign of the Fresh Kills landfill, 2,200 acres that for more than half a century was the primary garbage dump for New York City. The designer, James Corner of a company called Field Operations (who is also involved in the redesign of the High Line), renames the dump "Fresh Kills lifescape" and envisions a park that will (if it successfully passes through the approval process) begin construction in 2007 and unfold in four stages over 30 years. It needs that much time to adjust to the decomposition of the garbage. One notable feature in the new park will be a memorial for the World Trade Center in the shape of two mounds that are the same size as the Twin Towers laid on the ground. This exhibition is also available in a version online (To get to it, click on the appropriate place on the map.) The project is one of several throughout the world presented as part of an exhibition entitled “Groundswell: Constructing the Contemporary Landscape.” Curator Peter Reed sees the various projects as “a measure of artistic creativity and of our changing attitudes toward natural and man-made environments… Because of the role public space plays as a catalyst for urban development and in the quality of civic life, how these spaces are treated is ultimately a reflection of our culture.”

Â

Neighborhood Activists' Toolkit

|

Neighborhood Activists' Toolkit has moved to a new location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

Non-Citizen Voting

Rallying behind a plea of "No Taxation Without Representation" a group New Yorkers gathered in front of the main post office on Tax Day to push for what they see as the latest voting rights movement in this nation - the right of non-citizens to vote.

"I truly believe that if people are paying taxes they should be allowed to vote," Candy Mojica, a Harlem resident and graduate student at the Hunter College School of Social Work, said at the rally.

New York City Councilmember Bill Perkins agrees. That is why he is the prime sponsor of Intro 628, introduced in the City Council on April 20th, which would allow legal non-citizens, with six months or longer of New York City residency, to vote in all municipal elections, including the one for mayor.

The Vocal Proponents

Advocates of the proposal argue that the estimated 1.3 million immigrants living in New York City, close to 20 percent of the population, deserve to be represented locally in government if they are expected to pay taxes and live with the decisions of elected officials. This population is larger than the entire borough of the Bronx and 11 of the states in the U.S. It is estimated that non-citizen immigrants pay $18.2 billion in New York State taxes alone, yet they have no representation in government.

"The greatest movements we've had in this country have been to remove arbitrary barriers to voting, whether the civil rights movement, the suffragettes, or the move to allow 18-year-olds to vote," Perkins says. Allowing non-citizens to vote, he says, is just another extension of democracy.

Under the bill the city would also be required to issue new municipal voter registration forms in an expanded array of languages (Spanish, Traditional and Simplified Chinese, Korean, Bangla, Arabic, Russian, Haitian Creole, French and Urdu).

The Silent Opposition

While there is not a highly visible movement of those protesting efforts to expand suffrage to non-citizens, it is clear that many New Yorkers object. A passerby at the April 15th rally, for example, said "it is reasonable for people to be citizens in order to vote. There is something to be said for the commitment you make to your country."

"Voting is an awesome and essential piece of citizenship" argues Stanley Renshon, professor of political science at the City of New York Graduate Center; it should not be given away to those who are not integrated into the community and the country. "It is the badge of inclusion." If legal residents could vote without being citizens, there would be less incentive to apply for citizenship, and this would "weaken the bonds that tie us together as Americans."

To become a naturalized U.S. citizen, a person has to be a permanent and legal resident for at least five years and they must be able to speak, read, and write in English. In addition, they must also demonstrate an understanding of U.S. history and government. This knowledge of the political system, the shared culture and history of America and a sense of belonging to their communities, opponents argue, is key to extending the right to vote to individuals. Permanent and legal status and passage of the citizenship test ensures that people at least reach a minimal threshold in these areas.

"The premise of voting is that the voter be informed and acclimated to our political culture," Renshon said. " It takes time to develop this familiarity."

Part of Larger Movement

Non-citizen voting laws have been passed on the municipal level in Amherst, Newton and Cambridge, Massachusetts. However, as state law currently prohibits non-citizens from voting in local elections, bills have been introduced into the Massachusetts legislature to change this regulation.

Already a number of municipalities in Maryland allow non-citizen voting in local elections, including Takoma Park, Barnesville, Martin's Additions, Somerset and Chevy Chase. In Chicago non-citizens can vote in school-board elections if they have a child in the public school system. Indeed, this was true in New York City too, until school boards were dismantled here in 2002.

Â

City Council Stated Meeting - April 20, 2005

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

Quote of the Day:

“I have a confession to make: I am a sinner. Throughout my life I have committed many sins. But the sins I am accused of today, I did not commit. I am innocent.” – City Councilmember Allan Jennings responding to charges that he mistreated female staff members.

Meeting Summary:

Although most reporters and even many New York City Council members had already left City Hall when the bills finally came up for a vote, the City Council considered more than just the behavior of its own members at its recent meeting.

Nearly two hours after the meeting began, the council approved five measures aimed at reducing pollution from buses, trucks, and other city vehicles.

Intro 414-A requires that the city purchase cleaner burning vehicles in the future.

Intro 415-A requires that city’s diesel fueled vehicles now use “ultra-low sulfur” emission fuel.

Intro 416-A places more stringent pollution requirements on trash- and recycling-trucks used by the Department of Sanitation.

Intro 417-A reduces emissions on “sight-seeing” buses used for tourism tours.

And Intro 428-A places new pollution requirements on vehicles that transport children to and from school.

The council also passed two bills (Intro 328-A and 329-B) that will reduce the city's use of pesticides and require that residents receive information when certain chemicals are used in an area near a home or apartment.

“This is the most important environmental legislation that this council ever done,” said Councilmember James Gennarro.

But most of the meeting was dedicated to the discussion of the penalties filed against Queens City Councilmember Allan Jennings, who for the last year has faced allegations of sexual misconduct and mistreatment of female staff members.

After a nine-month internal investigation, the council’s eight-member Standards and Ethics Committee found Jennings guilty of improperly firing one employee on his staff and creating a hostile work environment. Five women charged Jennings touched them inappropriately, subjected them to racist remarks, and intimidated them.

Last week, the committee recommended that Jennings be allowed to stay in office, but suggested the most stringent penalties ever imposed on a member of the council. The full council was only asked to vote on the penalties, not to consider the validity of the charges.

By a vote of 43 to 2, with 4 abstentions, the council voted that Jennings must:

- Pay a $5,000 fine

- Undergo court-certified anger management and gender, racial and harassment sensitivity training

- Receive a public censure

- And be stripped of all of his committee assignments and stipends.

Jennings spoke a length in his own defense, arguing that the allegations were politically and racially motivated and unsubstantiated. He blasted the council’s process as a series of “secret hearings” where he was denied the right to cross-examine certain witnesses.

“The sins I am accused of today, I did not commit,” said Jennings. “I am innocent.”

Jennings ended his remarks by reading a Bible verse then paraphrasing the words of Jesus Christ; “I forgive you all, for you know not what you do.”

The only other council member to vote “no” on the penalty was Brooklyn Councilmember Charles Barron, who said he could not judge whether the charges were true or false because the hearings were closed to the public and other council members.

“You may get Jennings today, but they may come for you tomorrow,” said Barron.

Many council members said they were embarrassed by the events. Councilmember Margarita Lopez said the council should have acted more quickly to address the complaints. Other council members – like John Liu and Dominic Recchia - thought the penalties should have been more stringent.

“It’s a shame that he isn’t being expelled!” said Recchia.

Council members Eric Dilan, Oliver Koppell, Kendall Stewert, and Hiram Monserrate abstained from the vote.

Jennings’ lawyer said he plans to appeal the ruling to the State Supreme Court.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for May 11, 2005.

Â