Campaign 2005: Mayoral Candidates' Plans On Planning

The culture of mayoral politics in this city continues to invoke strict allegiance to the imperial power of the office. The game is how you get to City Hall so you, the mayor, can make things happen -- not how you can help neighborhood residents make things happen. And most people, whether in office or not, don’t have the foggiest idea how the arcane systems of zoning and planning work.

None of the mayoral candidates are making land use issues the front and center of their campaigns, though they mention them in their ideas about housing. But a little digging unearths some distinctly different approaches.

Bloomberg’s Down-zoning and Up-zoning

Buried among Bloomberg’s claims of accomplishments are two initiatives connected to land use -- down-zonings and up-zonings.

The down-zonings are of low-density neighborhoods in the outer boroughs to prevent “overdevelopment.” The down-zonings are aimed at preventing new housing development and conversions that build to the maximum floor area permitted under existing zoning. In other words, they keep developers out. While in some cases these down-zonings are long-overdue measures to help preserve stable communities, in other cases they end up having little effect except helping homeowners in the areas to decide who to pull the lever for in November. In many cases they respond to anti-immigrant prejudices, since many of their new neighbors happen to be immigrants.

The other controversial Bloomberg policy has been to up-zone areas in more dense in-lying residential communities, like Greenpoint and Williamsburg in Brooklyn, one of the deeds for which Bloomberg counts the numbers of jobs and housing that are projected to be created, but has nothing to say about the enormous local resistance he faced.

Ferrer’s Inclusionary Zoning And Community-Based Planning

Fernando Ferrer offers a clear alternative to Bloomberg. The Bloomberg administration continues to oppose mandatory “inclusionary zoning”--the use of zoning to make housing developers include units for people with low and moderate incomes. At first, Bloomberg’s planning experts claimed that inclusionary zoning doesn’t work, and they opposed a proposal to incorporate inclusionary provisions in the Fourth Avenue rezoning in Brooklyn, which would have allowed developers to voluntarily incorporate affordable housing units in return for getting more square feet of building space. Then, after considerable pressure over the mayor’s rezoning of Greenpoint and Williamsburg in Brooklyn, the administration went along with voluntary inclusionary measures.

In contrast, Ferrer proposes to mandate inclusionary zoning in target areas that are under development pressure. He would require that 30 percent of new housing units in these areas be affordable -- 15 percent for low-income and 15 percent for moderate-income households. In return, he would offer a series of bonuses and incentives to developers to make it worth their while. If they provide more than 50 percent affordable units, they would receive financial incentives and density bonuses. Under certain conditions, they could transfer their development rights to other parcels of land or contribute to a housing fund that would produce affordable units elsewhere.

Ferrer also proposes a comprehensive zoning overhaul and reduction of red tape, but it’s not clear what this would mean; in the past, City Hall has retreated every time they faced the Herculean task of changing the thousands of custom-made zoning provisions that developers and individuals are invested in, and communities have fought for or against, over the last half century.

Ferrer recently chose to announce his plan for housing while in the Melrose neighborhood of the Bronx., where he had supported community residents who opposed a city housing proposal that would have displaced many people when he was Bronx Borough president. He funded their alternative plan, which was then adopted by the city, and which has led to revitalization of the neighborhood. Subsequently Ferrer has been an advocate of community-based planning, and supported the principles of the Campaign for Community-based Planning in the last election.

Weiner On Opening Up The Process

Anthony Weiner, however, hits the hardest at the planning process under the Bloomberg administration. He derides “too many insider deals” and says that too many of the new projects are financed “off budget” -- through PILOTS (Payments in Lieu of Taxes) and new special authorities like the ones used in the mayor’s Midtown West plan. Weiner calls for “legal requirements that ban insider deals” and “laws that open up the bidding process,” ending the practice of no-bid contracts. Weiner also criticizes the environmental review process, saying that Environmental Impact Statements are “tools of development rather than what they were intended to be.”

Fields On Inclusionary Zoning

C. Virginia Fields claims credit for having sponsored an alternative plan for Manhattan’s West Side that did not include Bloomberg’s ill-fated Jets stadium. Fields has also come out in favor of mandatory inclusionary zoning in neighborhoods “shifting from affordable to market-rate housing” and a voluntary program in other areas.

Other Races

Beyond the mayoral candidates, at least two others who are running this year have come out with relevant statements.

Norman Siegel, candidate for Public Advocate, has been calling for a more open process of planning and has come out strongly against the use of eminent domain to promote new development.

Scott Stringer, candidate for Manhattan Borough President, recently released a series of recommendations for reforming Manhattan community boards. They include provision of a professional planner to each community board and greater support for the 197-a planning process, in which community boards can prepare plans and get them officially approved.

Putting Planning On The Agenda

The Community-based Planning Task Force has launched a campaign to get candidates to put community planning issues on their agendas for discussion in the campaign. Their recommendations are detailed in their report Livable Neighborhoods for a Livable City (in pdf format), and the candidates are being surveyed to see if they agree with the recommendations. They have not yet formally responded.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

Campaign 2005: 10 Budget Choices Facing The Next Mayor

Whoever is mayor on January, 2006 will face monumental decisions about New York City’s budget, thanks in part to the $4.5 billion deficits projected for each of the next two fiscal years.

A budget ultimately reflects the values of those who make it and approve it, and the mayor’s choices on the following ten budget-related issues go to the heart of his or her values and vision for the city.

1. Education Education plays an immense role in the city’s finances, with spending on it for operational expenses expected to reach $17 billion in 2006, or 32 percent of the total city budget. The city’s share of that funding has increased an average of almost four percent each year since 2000.

The big unknown in education is the city’s obligation, if any, to meet the state court order in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit. The court has ordered an increase in city education operational spending by $5.6 billion over four years and $9.2 billion in capital spending over the next five years. It is not clear what the state and city shares would be.

Specific issue: Whether the city will share in the new spending required by the CFE case, and how much that share will be.

2. City Workforce.

No city union currently has a contract for the 2006-2009 financial plan period. Yet, the Bloomberg administration’s current plan assumes future settlements will be at half the rate of inflation. Higher agreements will mean finding hundreds of millions of additional dollars.

Specific issue: Negotiating union contracts, and paying for future city labor settlements.

3. Public Safety

Major crimes continue to decline in New York City, even as the number of police officers declined by some 3,700 officers in 2005, or over nine percent, from a peak of approximately 40,000 in 2000, according to a report by the Independent Budget Office (in pdf format). The agency’s report also notes that another reasonable money-saving budget choice is available – civilianization, using lower-paid civilians to do work currently being done by higher-paid uniformed officers.

Specific issue: What the number of uniformed police officers should be, and whether to expand civilianization in the department.

4. Sanitation

One of the major increases in city spending in the past few years has been the escalating cost of residential waste disposal. Disposal has tripled in cost since the closing of the Fresh Kills landfill in Staten Island in 1998, to $300 million currently, according to a recent Independent Budget Office report (in pdf format). The use of new marine transfer stations and rail lines that would reduce the costs of the very expensive truck-based system used today raises important cost, equity, and environmental issues.

Specific issue: How to reduce the escalating costs of the current truck-based waste disposal system in the city

5. Overtime

The cost of overtime for police, firefighters, and the city’s other uniformed services in 2005 again reached more than $700 million, nearly $200 million more than was initially budgeted for the year, according to a report by the Financial Control Board. The underestimating of overtime costs is, in fact, a pattern that goes back well into the 1990s, and the Financial Control Board sees the pattern continuing in the Bloomberg administration’s new financial plan.

Specific issue: What management measures to employ in order to reduce the exceedingly high overtime costs for the uniformed services.

6. Property Tax

The city’s property tax will bring in an estimated $12.4 billion in 2006, or about 43 percent of all city tax revenues. It’s also the only city tax projected to increase substantially in the next four years (by $3.2 billion, says the Financial Control Board). The tax became a hot issue in November 2002 when Mayor Bloomberg and the City Council increased the rate by 18.5 percent – after a decade in which the average tax rate had been frozen. The $1.8 billion in new revenues produced by the increase helped solve a budget deficit that at one point had reached $6 billion.

The mayor’s $400 rebate to homeowners – continued in the four-year plan at a cost of over $250 million a year -- has wiped out that increase for many homeowners, but has left the burden on commercial owners and renters (who pay a substantial percentage of a landlord’s property tax). The rebates have exacerbated a bizarre, confusing property tax system in which private house owners pay lower property taxes than coop and condo owners; worse yet, renters, with lower incomes than homeowners on average, pay by far the highest residential rate.

Specific issue: What to do to reform the city’s bizarre property tax system, while maintaining its place as a vital source of city revenue.

7. Personal Income Tax

The personal income tax, or PIT, is the second largest -- and most progressive -- city tax, bringing in $6 billion (20 percent of tax revenues) in 2005. Its rates currently range from 2.9 percent of income for lower-paid taxpayers to 4.45 percent for households earning over $500,000. The two highest rates (4.25 and 4.45 percent), which added about $540 million in revenues to the 2005 budget, will be eliminated at the end of this calendar year. That will make the PIT less progressive, and make it more difficult to resolve the city’s long-term budget deficits.

Specific issue: Whether to restore the higher personal income tax rates for higher-earning New Yorkers.

8. Rainy Day Fund and Structural Budget Balance

The $3.5 billion surplus in the fiscal year 2005, along with the $1.9 billion surplus in 2004, have triggered a lot of interest, most recently by the City Comptroller in his July report, in establishing a so-called “rainy day fund,” which means saving all (or some of) any budget surplus and setting up procedures for using it over time – as, say, when an economic recession cuts revenues sharply. Under current state law, any surplus must be spent in the fiscal year of the surplus.

Mayors Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg have used billions of dollars of annual surpluses to pre-pay the next year’s expenses. That is politically attractive – I call the surplus a “sunny day fund” for mayors – because it’s an easy way to avoid new taxes or reduced spending for 12 months. The downside is that it’s a one-time revenue. Without the recent surplus, the mayor and council would have had to find $3.5 billion in service cuts and new revenues. If there were $3.5 billion of recurring cuts and revenues in the 2006 budget, next year’s deficit at this point would be $1 billion, not $4.5 billion; the four-year plan would be considered close to “structurally balanced,” that is, long-term revenue and expense projections would be roughly equal.

Specific issue: Whether to create a rainy day fund as the most reasonable way to achieve a more structurally balanced financial plan

9. Capital Budget

The July report by the Financial Control Board calls the Bloomberg administration’s latest 10-year, $62.4 billion capital budget strategy – the separate city budget that funds (by borrowing money in the financial markets) the rehabilitation, replacement, and new construction of public facilities – “by far the largest ten-year strategy ever presented.” The education portion is $18 billion, or 29 percent of the total. Since the debt service for this capital work is paid out of the operating budget, fiscal monitors worry about the burden of such an investment: $4.3 billion in debt service in 2006 (14.4 percent of city tax revenues), rising to $5.9 billion in 2009 (17.4 percent of city tax revenues).

Specific issue: Whether to support the city’s current 10-year capital budget strategy and its priorities.

10. Budget Process

The current mayor’s Charter Revision Commission has spent eleven months discussing possible changes in the city’s charter, and their work has focused in large part on two important questions: 1) public (and fiscal monitor) access to city budget information, and 2) the quality (and usefulness) of many charter-mandated budget and management reports. (The commission has said it is no longer considering the second question for the ballot in November, but it remains an important issue.) A running theme among critics of the commission’s proposals has been deep concern about possible expansion of the already extraordinary power that the city’s mayors have over the city budget.

Specific issue: What to do to expand the public’s knowledge of, and participation in, the city’s annual budget process.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

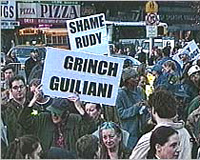

Giuliani -- Savior Of The City, Or Its Enemy?

Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club held a conversation on July 27 at the Jefferson Market branch of the New York Public Library with authors of two newly-published books about New York City under former Mayor Rudy Giuliani. An edited version of the conversation appears below:

Gotham Gazette: Fred Siegel, who is also the author of The Future Once Happened Here, and who was party to some of the discussions in which Giuliani's ideas evolved, has written The Prince of the City: Giuliani, New York and the Genius of American Life, a book that argues that Giuliani brought New York out of the low point of its history.

Rob Polner, who covered the mayor for Newsday, has brought together a group of 25 writers (including Jimmy Breslin, Jim Dwyer, LynNell Hancock, Luc Sante, and Kevin Baker) to contribute chapters for a book entitled America’s Mayor: The Hidden History of Rudy Giuliani’s New York. It examines various aspects of the Giuliani administration critically, finding the former mayor (in Polner’s words) “his own worst enemy and the city’s as well.”

Both of the books establish that 9/11 is now the point of entry when talking about Giuliani, but they focus more on other aspects of his legacy: the policies on crime and the effect of those policies on race relations and civil liberties; his actions on welfare reform; and debates about his spending and his relationship to "special interests."

Origin Of Their Two Views Of Giuliani

Please tell us how you reached your views on Giuliani and why you decided to work on books about a mayor who hasn’t been in office for four years.

Fred Siegel: I reached my views on Giuliani from my experiences as a New Yorker. I live in Flatbush, and I watched my neighbors prepare to evacuate in 1993. There was a sense the city was finished. . . [Giuliani’s predecessor Mayor David] Dinkins himself asked publicly in his speeches, can New York survive? [A telling moment came when then-parks commissioner] Betsy Gotbaum is standing in front of a lake in Central Park, cameras are rolling, and she’s talking about improvements made in Central Park, and as she’s speaking a dead body bobs to the surface. This is the era of “No Radio” signs, saying, in effect, rob someone else’s car. Auto theft, radio theft in particular, was essentially legalized because it was not something the police had time to bother to prosecute.

My interest in this came out of those years, the sense that the city was finished and something had to be done. [After writing policy papers for the Clinton presidential campaign], in 1992-1993 I got involved running seminars for Giuliani, giving him tutorials on a whole variety of subjects.

The rationale for the book can be explained in an old Soviet joke. A skeptical young man is puzzled about something, and asks [an official]: I know about the future, the future is always glowing, it’s always wonderful, it’s always getting better and better. It’s the past I have a problem with; it keeps on changing. And [that’s what’s happened in New York.]… David Dinkins, who brought the city close to the edge of disaster, is an honored guest at City Hall…In many ways the Bloomberg administration, policing and welfare aside, is a more competent version of the Dinkins administration, with a difference that Bloomberg can write his own check to interest groups when the city budget is inadequate. So, I wrote the book in order to give people a sense of what happened in New York, how it got to where it was, why it almost collapsed.

The rationale for the book can be explained in an old Soviet joke. A skeptical young man is puzzled about something, and asks [an official]: I know about the future, the future is always glowing, it’s always wonderful, it’s always getting better and better. It’s the past I have a problem with; it keeps on changing. And [that’s what’s happened in New York.]… David Dinkins, who brought the city close to the edge of disaster, is an honored guest at City Hall…In many ways the Bloomberg administration, policing and welfare aside, is a more competent version of the Dinkins administration, with a difference that Bloomberg can write his own check to interest groups when the city budget is inadequate. So, I wrote the book in order to give people a sense of what happened in New York, how it got to where it was, why it almost collapsed.

Rob Polner: I covered the Giuliani administration for Newsday down at City Hall from the middle of the Ruth Messenger-Rudy Giuliani reelection campaign until the very end. And in that time I wrote more stories than I can carry with me… Because Room 9, the press room where I worked, is only just a few feet from where the mayor sits, you can really get about as close to understanding this mayor in his public role as anybody. You see him virtually every day. And this is a mayor who has a lot of uses for the press – a very secretive mayor, bordering almost on paranoid, but nevertheless one who uses the press to promote his agenda and to send his message almost on a daily basis. In fact if it was Thursday and there hadn’t been a big brouhaha, the reporters in Room 9 knew that the mayor would somehow throw a punch to start a fight. He was a very exciting and interesting mayor to cover.

By September 10th, 2001, the city was moving away from Giuliani, and the mayoral candidates were getting traction by criticizing Giuliani and his policies. I’m not going to bend over backwards to defend the Dinkins administration, but Rudy Giuliani actually raised spending more on a per-year basis than Dinkins did. Giuliani’s last budget had a nine percent increase in spending, much of which was hidden… Giuliani’s impact on the public schools wasn’t very good.

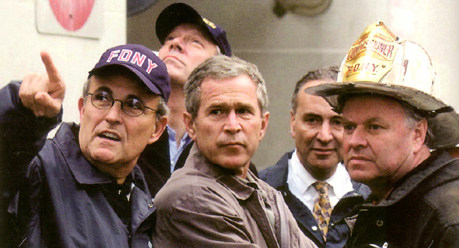

On September 11th, he performed admirably [at a time when] no one knew where Bush was and no one knew where Cheney was. The world hailed him as the newest Churchill. He was reinvented on 9/11 and he is still living off of that glory; in fact he may run for president based on his performance on 9/11.

I was as disoriented and traumatized as anyone by 9/11, but one of the ways in which I got my bearing was that he did something that made me think that maybe the city was going to recover from this Alice in Wonderland feeling. What he did was he sought to extend his term beyond the statutory limit. That was the Giuliani I knew, that was the Giuliani New Yorkers knew. He was going to try to pull an Al Haig and he was going to try to maneuver his way to stay in power beyond the end of his constitutional limit.

So that’s why I wrote the book, to address some of the mythologizing, Rudy’s own exaggerations and those of his supporters, and begin to set the record straight, because I think it is important for the future of the city.

Trying To Extend His Mayoralty By 90 Days: Greater Aid From Albany And Washington?

Fred Siegel: This, I think, gets to the heart of where Rob and I disagree. What Giuliani was proposing, and he was right, was a 90-day extension provided by the State Constitution. Why? Because for a brief moment, Congress, which generally has no use for New York, was in the palm of our hand so far as that they could not say “no” to Giuliani. His proposal to the Congress was to give us long-term relief, to change the funding formulas; for twenty years New Yorkers have talked about the fact that every dollar we send to Washington we get 79 cents back one year, 80 cents the next year. The focus in lower Manhattan [could have been] major transportation reconstruction quickly, reconnecting lower Manhattan to the transportation grid of the region.

Those are the things that could have happened; neither of them happened.

More time has now passed since 9/11 than it took to defeat the Japanese and the Germans in World War II. Go down to lower Manhattan and see what’s been done under Bloomberg and Pataki, and you want to see what leadership means.

Rob Polner: I think that the myth that Giuliani and his people were propagating at the end of his term was that the city could not survive without him -- the very social fabric of the city, the safety of the city.

Well, lo and behold we did, we’re still here, amazingly. And Rudy Giuliani left office on time because his scheme fell apart.

I don’t have a lot of faith, as Fred does, that he would have made a difference in those 90 days. First of all, 90 days is like five minutes in New York politics. Second of all, this is a guy who went to Albany and Washington and said stop giving us money, we don’t know how to spend it. However admirable you might think his message was about New York City becoming more self- sufficient, all that did, in my opinion, was open the door for, for example, the commuter tax to be eliminated by the legislature -- costing the city $400-500 million a year.

Fred Siegel: That was done by [Assembly Speaker] Shelley Silver. Was he Rudy’s puppet?

Rob Polner: [It was an attitude Giuliani helped create.] They basically said, “You guys admit you are not responsible, so we’ll cut the funding.”

The City Before Giuliani

Gotham Gazette: Let’s go back to before Giuliani came into office, to which you devote the first quarter of your book, Mr. Siegel. You say that New York was a once-great city that was taken over by “interest groups, a political monopoly more suffocating than Tammany at its worst.” What exactly did you mean by that?

"This city has a very unusual combination of hyper-politicized and completely demobilized. It is run by those people with a stake in government."

|

Fred Siegel: It’s important to understand how New York works and continues to work (and Bloomberg is definitely a restoration of business as usual.) I spend the first hundred pages of the book going from LaGuardia to the end of Dinkins, trying to explain the political culture in New York and what is so destructive about it.

New York goes into recessions earlier than the rest of the country and it comes out later. The rest of the country went into recession the first quarter of 1991, and was out of the recession by the third quarter of 1992. We went into recession a quarter before; we didn’t come out of the recession until the third quarter of 1996. Now why is that important? It is important because New York is three percent of the population of the country, yet we lost 25 percent of all the jobs in America lost during that recession.

During that period one group was held harmless -- the public sector unions, public sector interests. There were a few lay-offs but Dinkins engaged in billion-dollar tax increases to keep the public sector, his political base, happy.

The key here to understanding the political life of the city, I think, is that those people who work directly or indirectly for government are the people who vote. In the 2003 elections, turnout (depending on the districts) ranged from three percent to seven percent. This city has a very unusual combination of hyper-politicized and completely demobilized. It is run by those people with a stake in government.

The city was bankrupt when Giuliani came into office. Most of this is not known; the Financial Control Board wanted to take the city over. Giuliani never talked about this crisis, never talked about it publicly. The city could not pay its bills; it was out of cash. I spent a lot of time around City Hall in 1994 and 1995, and every interest group in the city was in a rage. They were right to be in a rage; their interests were being taken on. It was a magnificent job of managing a crisis situation. Welfare reform begins not as welfare reform, but as budget reform. A lot of what drives what Giuliani does -- why he endorsed Mario Cuomo in 1994, for example -- has got to do with the city’s impending bankruptcy; he needed Cuomo to fend it off and he didn’t trust Pataki (quite rightly, as we’ve seen over the years).

Gotham Gazette: Mr. Polner, had liberalism failed the way Mr. Siegel believes, before Giuliani took office?

Rob Polner: First of all, remember that the long post-war boom ended by the end of the 1960s and deindustrialization was well under way. We had a significant long-lasting recession. The city had been turned very rapidly into a front office for corporate America -- that was the plan for Manhattan below 59th Street – but after the 1960s, a third of those Fortune 500 companies left. They went to the suburbs, where they were closer to their labor pool, their secretarial pool; it was inexpensive to hire their staff. Many of the executives interviewed in one study said they simply didn’t want to commute to the city; they wanted to be closer to where they lived. So the city lost a lot of its prestige and base in those years; it was very hard times.

The Democrats, starting with the New Deal and going on to Bobby Kennedy and later Mario Cuomo and David Dinkins, tried to engage the problems of America’s cities, which were huge problems with joblessness, particularly among minorities in this town, drug addiction, later AIDS, and crime.

There were mistakes made by Democrats -- urban renewal, for one – that I wouldn’t want to see repeated. But it’s too convenient, I think, for people of the right, Republicans in particular, to say with a broad brush that none of this worked, that in fact it just exacerbated these problems. In fact Republicans, whether we are talking about Ford or Reagan, really had no interest in terms of their political base and their ideology, in addressing the problems of the big cities.

So it is very easy to say liberals have failed and we have to go in a new direction, but I would say, that you have to give the Democratic party, and liberalism, and the New Deal credit for trying, and they were successful on many fronts, and Giuliani benefited as he came into office from their having waged these battles over the years.

The Drop In Crime

Gotham Gazette: The most striking difference everybody points to between the Dinkins years and the Giuliani years was that crime, which had been dropping slightly at the end of the Dinkins administration, plummeted. Before 9/11, crime was seen as Giuliani’s major accomplishment. Do you think he deserves that reputation, Mr. Polner?

Rob Polner: I think Giuliani deserves some credit for making crime his signature issue from the beginning, even when no one on the left and no one on the right could have predicted or known or expected that crime would drop the way we’ve seen it drop -- and the way it continues to drop, with Mr. Giuliani out of office and a new police chief, a new mayor, and very different tactics.

I think Giuliani deserves credit for an innovation that you know as CompStat, which is the pinpointing of crime trends and holding police commissioners accountable.

But Rudy Giuliani very actively, virtually daily, perpetuated the notion, without actually saying it, that he was personally responsible for making New York City safe again, and it is just not true. There were 300 fewer murders in the first year of his office than the year before, 1994, before CompStat was fully rolled out. What accounts for that? Similarly, crime went down all over the country, in states and cities with very different tactics, completely opposite tactics in some cases. Something else was going on.

I recommend that you read Andrew Karmen’s book called New York Murder Mystery. He is a criminologist and he examines what happened. He points to a confluence of very different factors that might have had an effect on crime. For example, demographics: By the 1990s, 70 percent of young people have experienced at least a year of college, compared to the 1970s when it was maybe 30 percent. Certainly another factor was the end of the crack epidemic, which cut across Dinkins mayoralty horribly. And perhaps the addition (I’m not convinced of this) of 5,000 police, which Dinkins, under a great deal of pressure from the media and the City Council, set the stage for by passing the Safe City Safe Streets Act and raising taxes. That’s not in Giuliani’s playbook, I don’t think he would have done it, but Dinkins raised taxes at least temporarily to pay for all these cops, at least 2,000 of whom hit the street during the Dinkins administration. Even AIDS may have been a factor, because sadly so many heroin users on the street who were responsible for muggings and shootings for money to make their fix, died from AIDS.

"Rudy Giuliani very actively, virtually daily, perpetuated the notion, without actually saying it, that he was personally responsible for making New York City safe again, and it is just not true."

|

You know it is an interesting fact that murders in 1997 and 1998 fell three times as fast indoors as outdoors. Police can’t affect really very well shootings that take place inside; they can’t be expected to do that. What does that tell you? It tells you that there was a de-escalation of hostilities, it wasn’t just New York, it was nationally, and we should be careful about giving Rudy Giuliani the credit.

Fred Siegel: Let me disagree with Rob on each and every point.

Here are a few facts: New York is three percent of the population and accounts for 25 percent of the drop in crime. Crime did not drop everywhere. It didn’t drop in Philadelphia, didn’t drop in Baltimore, didn’t drop in Cincinnati, it didn’t drop in Chicago. In Chicago, a city with one third of the population than New York, they had more murders than New York. It didn’t drop nationally. And those places where it did drop, like Texas, it dropped because of extraordinary incarceration rates. One of the interesting things about what happened to crime in New York in the 1990s is our rate of prison incarceration did not increase. We didn’t put more prisoners away, but there was less crime.

Now Rob says this began with CompStat. Actually this began with Broken Windows. When [William] Bratton was the head of the Transit police -- remember in those days the Transit police was a separate department -- Bratton begins to apply broken windows. And he discovers what George Killing, the father of Broken Windows, understood already -- that there is no distinction between the guys that commit the small crimes and the guys who commit the big crimes.

So of the people who were caught jumping turnstiles, one in seven were wanted on outstanding felony warrants. Bratton brought crime down dramatically in the subways. At this point I was the editor of the City Journal and I was publishing articles about Bratton and what Bratton was doing.

Dinkins had no interest in this because Dinkins believes in the root cause of crime. Although he had authorization to hire 5,000 more cops he hired 2,000, and he didn’t think that they really count for much. We also had two riots in the last years of Dinkins term.

Giuliani chose Bratton [to be police commissioner] partly because Bratton was far more innovative [than his predecessor Ray Kelley], although Kelley is very competent. The biggest mistake Giuliani made was pushing Bratton out because the system that Bratton created continues to drive crime down.

The key here is the combination of Broken Windows and CompStat, policing the small crimes and patrolling statistically -- figuring out where the action is and anticipating where criminals are going to go so crime is actually reduced.

Now it’s important to note here that this all takes place before the economy recovers. This is not a function of better economic times. One of the reasons I think why we are not back in the Dinkins years is that crime reform, and to a lesser extent welfare reform, are still in place. I can’t prove this [but I suspect] it’s part of an explicit deal between Giuliani and Bloomberg. Bloomberg does not do anything to crime reform and welfare reform and is free to screw up everything else and pretty much does; on the other hand Giuliani says nothing [against Bloomberg] when he runs for President (and he is running), [and] Bloomberg will write him an enormous check. We’ll see this unfold, I think, in the next few years.

Michael Hersh: Fred, you were making a point and then you stopped. Giuliani was interested in crime, he had George Kelling’s theory of Broken Windows, he had CompStat, whereas Dinkens was more interested in… and then you shifted gears. I assume you were going to say he was more interested in poverty and systemic issues. What’s wrong with that?

Fred Siegel: Michael, the key thing is at that point CompStat didn’t exist. CompStat began to come into play in the second year of the Giuliani administration when Jack Maple, an extraordinary character out of a Damon Runyon novel, started putting pins in a map and started saying we can do this, we can computerize this. What he had is Broken Windows. What Giuliani had is he studied what Bratton had done in the subways. I pat myself on the back here, I brought this to his attention, I brought Kelling in to speak with him. He understood this.

Dinkins was firmly wedded to the notion of the root cause of crime, that if you don’t reduce poverty you don’t reduce crime. The trouble is the causation works more the other way -- that crime causes poverty, rather than the other way around.

If I want to map high poverty areas of the United States, I map the riots in the 1960s. With very few exceptions, none of those areas have recovered, or are just now recovering. So, violence is deadly for cities because it takes away the city’s greatest asset. The city’s greatest asset is public space. If you can’t enjoy public space then you might as well live in suburbia. If you don’t reduce crime you might as well tell people, “you want a better life, leave.”

One of Giuliani’s virtues for which he was intensely disliked, is that he took crime in East New York every bit as serious as he took crime on Fifth Avenue. And the sharpest drops in crime, the sharpest rise in the value of homes, the sharpest rise in the state of well-being occurred in the poorest neighborhoods in the city. That’s something you think liberal Democrats would applaud.

Tom Leimsider: You mentioned that Bratton was responsible for a lot of the reduction in crime during the Giuliani administration, yet Giuliani kind of chased him away. That seems to be a criticism of Giuliani in that it’s Giuliani’s way or the highway; he doesn’t have room for other people to share his limelight.

Fred Siegel: I think you are right. You have to understand something. Giuliani and Bratton are actually the same person. They are both ramrods. They are both guys with devoted followers. When Giuliani comes in office he gives every one David Osborne’s Reinventing Government; Bratton gives everyone Hammer and Champy’s Reengineering the Corporation. They are very similar people. When they are both in the same room no one else has air to breathe.

But yes, I think this is one of Giuliani’s biggest failings. He wouldn’t allow Bratton the limelight he deserved. And I think this will come back in the presidential election, I think this will be brought up as a very legitimate criticism.

You see what Bratton is doing now in Los Angeles. L.A., you have to understand, has 9,000 cops for a city that has half the population of New York. It has a police force one quarter the size of New York’s for half the population. It is wildly under policed, yet Bratton has reduced crime 30 percent. Partly it’s the methods; partly it’s the leadership. And a lot of the trouble in Giuliani’s second term was a function of having replaced Bratton with a guy who is technically competent, Howard Safir, but was a stiff, who was cut off from the life of the city, cut off from the life of the department. Two days after the Diallo [shooting], he goes to the Academy Awards in Hollywood, not understanding what’s happened in the city. So this pays malign dividends for pushing Bratton out, yes.

Racial Tensions

Gotham Gazette: Mr. Siegel, by the time of Diallo, you mention in your book that there were some legitimate grievances concerning stop-and-frisk policies. Do you think this was something where aggressive policing had gone too far, or was tension unavoidable?

|

Amadou Diallo |

Fred Siegel: Tension is avoidable. My wife, Jan Rosenberg, who’s a sociologist, is the one who laid this out for me. She talked about the idea of fruitless frisks. What happens as crime goes down and there is a decline in the percentage of people you stop who are armed and up to no good? What are you supposed to do? Bratton’s answer to this is, the police had to be more active in responding. They had to say, I stopped you, because here is what we are searching for, someone who looks just like you. The police had to be more accommodating, more responsive when they stop people.

That’s what Bernard Kerik did. Kerik was the unacknowledged response to Diallo. Had Bratton stayed in office, I think we would have had tragic incidents in the second term but they wouldn’t have played out quite the same way.

Gotham Gazette: What do you think led to such an increase in racial tensions during that period? Do you think that it was the policing or, as you mentioned in your book, leadership from the black community?

Fred Siegel: It is a number of things. You have to remember how high racial tension was in the Dinkins years during the Crown Heights riot, during the Washington Heights beeper-boy-drug-runner’s riot, when Dinkins buries a drug dealer with honors. That’s an awful chapter in the city’s history.

Many people who opposed Giuliani in 1993 couldn’t make a good case about Dinkins, so they had to scare the hell out of people about Giuliani. He was going to bring fascism to the city. This was a common theme. And of course his behavior at that police riot, although the riot had occurred before he arrived, his vulgar language didn’t help that. But by and large, you had to tear Giuliani down; you couldn’t build Dinkins up. People were being asked to vote their fears not their hopes.

And it is important to remember that in 1993, the city was encased in pessimism. There was no sense that anything could be done. In fact, what people were afraid of was that if Giuliani would act he would set off even more riots. So there was this attempt from the start to say Giuliani was evil, especially [from Harlem Congressman] Charlie Rangel, who’s a much smoother version of Al Sharpton. He was constantly hammering at this kind of theme when the 125th Street murders take place.

Does everyone remember this -- the Freddy’s fire? This has been dropped down a memory hole at the New York Times. Here’s what happens essentially: In early 1995, Rudy Washington, little known deputy mayor in the Giuliani administration, was probably the toughest, gutsiest guy in an administration of tough guys. He is the guy that cleans up the Fulton Fish Market on the ground. Rudy Washington wants to go up to 125th Street because the merchants there are dying; the streets are covered with vendors, killing the merchants. There are feces on the street, there are rats, it feels like a third world situation. But every time the police come, Sharpton and his top aide Morris Powell, an escaped mental patient with a long history of violence, threaten violence.

Giuliani gets the Harlem pols to quietly agree in writing to say they won’t demagogue the issue if the police come in. The police come in, they clear the street. It allows for the revival of Harlem, along with what [housing commissioner] Debbie Wright did in housing.

Now Morris Powell is out of business. Freddy’s rent dispute comes along, Sharpton and Powell turn an ordinary rent dispute into a racial dispute. They are ranting outside about kill the Jews, kikes, blah, blah, blah -- same kind of stuff that occurred outside of Church Avenue [during the boycott of a Korean market] with a different kind of ethnic group. Seven people are killed. Charlie Rangel’s office is diagonally across the street. When it is over Charlie Rangel is very angry -- at Rudy Giuliani. He never holds Sharpton accountable; no one ever holds Sharpton accountable. But it’s because of what is done on 125th Street that Harlem has a chance to revive, despite the African American leadership.

Rob Polner: I covered Freddy’s fire as a reporter. That fire occurred around the corner from a police precinct. And the workers who were killed, the young people who were killed in that intentionally set fire amid this very heated racial situation, were afraid to go to work for several days because of the threats that were being made. But they had to go to work, so they came down from the Bronx and elsewhere, and several of them died. Rudy Giuliani escaped a lot of the blame for that, which I think he deserved.

Rob Polner: I covered Freddy’s fire as a reporter. That fire occurred around the corner from a police precinct. And the workers who were killed, the young people who were killed in that intentionally set fire amid this very heated racial situation, were afraid to go to work for several days because of the threats that were being made. But they had to go to work, so they came down from the Bronx and elsewhere, and several of them died. Rudy Giuliani escaped a lot of the blame for that, which I think he deserved.

Dinkins had created community liaisons to Harlem and many neighborhoods of the city to try to keep City Hall on top of what was going on. Rudy Giuliani was a very hyper-centralized mayor and everything had to come from him, so he basically dismantled all that. And he had no intelligence. So these threats were being uttered and Sharpton was out there and so was this crazy guy that Fred mentioned, Powell, and nothing was being done.

Now it happened over a relatively quick period, it wasn’t like the fiasco that was the Church Avenue situation with the Korean deli and the threat they received and all that, and Dinkins deserves a great deal of blame for that. But Giuliani had no intelligence so he couldn’t move in and he didn’t break it up. And guess what, a lot of people died. So why isn’t Giuliani being blamed for that?

Gotham Gazette: What about racial tension in general during the Giuliani administration?

Rob Polner: Rudy was a very, very polarizing and divisive figure for this town. And part of the reason was that, even after the conditions of the city had calmed down greatly, the police were continuing to go with these hard line tactics, where they stopped and frisked kids and adults, particularly in heavily black communities.

You can blame police chiefs for this but really Rudy should be blamed because if he’s going to get credit for the crime drop he has to take the blame for the effects of what the police call a toss.

There were estimates of as many as 100,000 stop-and-frisks of people because they didn’t fit a particular profile of a law abiding citizen -- they looked at you the wrong way, or they were wearing hip-hop clothing. I don’t know the numbers, because the police didn’t usually write a report about these stop-and-frisks. People were being stopped and frisked without reasonable cause or suspicion and thrown into jail, and they spent a night or two in jail and then the judges threw the cases out as absurd. It was an attempt to find people with outstanding warrants or guns -- tactics that, if you could argue were justified when there were 2,000 plus murders a year, should never have been justified in light of the huge crime drop.

That is one reason why the parents of young people who were black or Hispanic in this town, and maybe not wealthy, were very fearful and angry with Giuliani. By 9/10/2001 they wanted nothing more to do with him.

And there were other reasons. His administration was almost completely white. In his attempt to tweak liberalism at every possible opportunity, he attacked the foundation of institutions that, in this city, serve primarily the poor and people who are non-white. What do I mean by that? We talked about firing Bratton, but at the Board of Education Giuliani just went through chancellors like they were pencils. He shook it up and beat it up and by the second term he was back-filling all sorts of money into the Board of Ed, and [promoting] these novelty programs like vouchers that would appeal to Republicans because he wanted to run for the Senate.

He attacked CUNY and their funding base. Then of course he has taken credit for improvements in CUNY, which I personally think had less to do with the standards that were set for admission and more to do with changing population demographics of people attending CUNY.

What I am saying is that he attacked the institutions, and I would include welfare in this, that people who are black and poor or working class, relied upon and had relied upon for decades all in the name of reinventing the city, which he never did.

Welfare Reform

Gotham Gazette: Welfare reform is obviously one of the other polarizing aspects of the Giuliani administration. Do you think that one’s opinion as to how well welfare reform works here in New York is a result of what one’s ideological perspective is?

Rob Polner: I don’t think Giuliani came to office with the idea that he was going to slash the welfare rolls…Rudy Giuliani was basically a pragmatic politician who was fearful that he would be left more or less on the sidelines going forward as a liberal Republican in a Democratic city.

Rob Polner: I don’t think Giuliani came to office with the idea that he was going to slash the welfare rolls…Rudy Giuliani was basically a pragmatic politician who was fearful that he would be left more or less on the sidelines going forward as a liberal Republican in a Democratic city.

It was only after Newt Gingrich’s Contract With America, and Clinton making welfare reform a federal law, that Rudy Giuliani embarked willy-nilly on a campaign to close the door to people seeking welfare. In the end Giuliani threw off 350,000-400,000 people without any real review, without any real ability for them to get any skills, without meaningful childcare. This is his legacy. When we look at the fact when Bloomberg came into office there was a record level of homelessness among families you have to look back on Giuliani’s policies on welfare as well as housing to help understand why that happened.

Fred Siegel: Let’s start with the last point first. The reason why homelessness increases under Bloomberg is because the doors are open again. One quarter of all people on homeless rolls were not in New York a month before they went on the homeless rolls. They were attracted here.

Let’s go back to welfare. Welfare supported the aspiring poor the way a rope supports a hanging man. It cut them off from the larger society, it cut them off from the larger life of the city. So in the midst of economic booms they stayed outside of the economy.

As to when welfare reform began, it began in the first year. Rob is misinformed here. The reason it doesn’t appear publicly is twofold. One, in order to do it you have to get cooperation from [the labor union] DC37. To put people in the parks doing cleanup work, pickup work, requires a series of complex labor negotiations. Those negotiations began about three or four months after he was in office.

What drives welfare reform well before Newt Gingrich arrives, well before George Pataki arrives, is the fact that the city can’t afford to have 1.1 million people on welfare, one out of every seven New Yorkers. It is simply not fiscally sustainable. That’s what drives it.

But it speaks to something fundamental about the Giuliani administration. There are many problems he doesn’t solve; I think this is entirely true. Successful cities have a succession of good mayors [and] improve themselves over a period of decades. What he did with welfare reform, he created alliances with some of the public sector unions against the social services industry.

New York is different than the rest of the country. We made poverty into an industry. We assumed the poor would always be poor and we created a whole job sector around poverty. Wayne Barrett in the Village Voice proudly says, “Poverty to New York is what oil is to Texas.” This is disastrous. This is what Jane Jacobs called transactions of decline.

Having done this, having played off some of the unions against the social services industry, what was on the plate for a successor were two things, particularly after 9/11 -- more productivity in labor contracts, more efficiency from the public sector, and transportation. The current mayor showed no interest in either of these things, rhetoric aside.

Giuliani And Civil Liberties

Murray Polner: I happen to be the father of Robert, Fred is a very old friend and I admire his book and all the work he has done. Could both of you address Giuliani and his attitude and his actions toward civil liberties in New York City.

Rob Polner: He likes my book too.

I just read in the paper that there was another court settlement that is costing the city millions of dollars for unwarranted strip searches by the police. This was one of the many, many civil liberties, I would say scandals, that occurred across the Giuliani administration.

He prevented people from having protests and from getting access to government records so they could gauge the credibility of his claims about his magical governance against the facts.

That was a problem with the Giuliani years. He was very, very restrictive about the flow of information. His commissioners spoke at the risk of being dressed down or removed if they said the wrong thing or if they spoke with too much candor. His mayoral management reports, which had actually really been under Dinkins fairly interesting tools for assessing the pluses and minus of city services neighborhood by neighborhood, were turned into basically propaganda, rosy -- and very thin --reports.

That was problematic with Giuliani. If he should run for President, I don’t think it will be golden years for civil liberties in America -- if he wins, that is.

|

"Virgin Mary" from Sensation Exhibition at The Brooklyn Museum. |

Guiliani's portrait on balls of dung from The American Effect at the Whitney Museum

|

Fred Siegel: I used to write for Murray, Rob’s dad.

Much of what Rob just said is true, but you have to put it into context. The civil liberties union didn’t have a problem with incredibly high crime rates. ACLU’s take was, the police don’t bother the criminals and the ACLU won’t bother the police and everyone is happy -- except the population. This is not a viable situation.

Some of Giuliani’s abuse of civil liberties was entirely tactical… cynical. Take the Brooklyn Museum case [the Sensation exhibition], I’m surprised somebody didn’t bring it up.… Giuliani didn’t want to admit that he wasn’t going to change his position on abortion to get conservative Catholic voters so [he attacked the exhibition as anti-Catholic].

I think though you have to put some of the civil liberties questions in the context of A) the ideological extremism of the ACLU, which now opposes bag searches on the subways and, B) the fact that from 1995 on, Giuliani is getting intelligence reports that terrorists are interested in City Hall, are interested in lower Manhattan, and this plays into it.

"Special Interests"

Fred Siegel: I agree the mayor’s management report was gutted. Here I just want to put it in context. Giuliani governed against the grain of every major interest group in the city -- the left-wingers on the courts, the interest groups, the politicians in Albany, most of the politicians in the city. That is what made his accomplishment so extraordinary. So yeah, he was always fighting and the law department was crucial in not allowing liberal interest groups to govern through court decrees of the sort that had made welfare reform impossible, that made child welfare reform impossible. The reason we have child welfare reform in New York today is the civil liberties groups were pushed aside while the decision [by the courts to change the system] was allowed to expire. And [Administration for Children's Services Commissioner Nicholas] Scapetta reformed the delivery of services for child welfare.

My disagreement with Rob is fundamental I think. I think liberalism’s internal understanding of what it does and how it does it failed, and has never come to grips with that failure, never wanted to debate its failure. It is too easy to be critical of Giuliani. Giuliani was not a saint. He was an extraordinary manager who took on every major interest in the city and when he was in conflict with them he usually won.

Rob Polner: I think Giuliani had his own uses for special interests and for identity politics, the kind of thing that his predecessors got a lot of criticism for. Every single municipal union, I think, endorsed him for reelection. Did he run rough-shod over their interests as he approached reelection? No, his deputy mayor, Randy Mastro, was working out contracts and pension sweeteners and all sorts of raises with each of those unions to make sure that they were going to be on his side when he faced reelection in 1997.

He also rolled over for a lot of powerful interests in this town, developers, baseball team owners. And numerous corporate interests, particularly when it came time to giving out tax abatements and direct cash grants to companies, many of which had no intention of decamping for New Jersey or wherever. He just opened the city’s checkbook during a boom time. And gave out much more of the city’s tax dollars, or offered it, to very powerful interests that, arguably, didn’t need it. So I think it is fair to say that he had his own uses for special interests.

"What he didn’t do, he didn’t put identity politics at the core of his agenda. He said he’s going to try to govern one way for everyone in the city. "

|

Fred Siegel On baseball, I think what Giuliani wanted to do with Yankee Stadium was indefensible -- moving the stadium, helping Steinbrenner. He doesn’t need the help.

[But] on real estate issues [in general], Rob is wrong. The real estate interests supported Dinkins in 1993; many of them supported Messenger. They did not like Giuliani. After [he broke up] garbage-carting cartel, the real estate interests did not support him. They were never close to him. They never liked him going back to his days as prosecutor when he took guys from Wall Street in handcuffs.

What he didn’t do, he didn’t put identity politics at the core of his agenda. He said he’s going to try to govern one way for everyone in the city. Did he always live up to that? Absolutely not. Was that more likely to be the case under Giuliani than say under Dinkins or under Bloomberg now? Absolutely.

Rob Polner: I think he [had his own identity politics]. He very often used race in a coded way to appeal to his own constituency. One of the ones that just jumps to mind was when the police sent a helicopter buzzing over a crowd at a particular noxious black separatist rally by a guy named Khalid Muhammad in Harlem and police jumped on the [stage] and threw over the chairs and pulled the plug on the system because they went over their time limit by a minute or two. What was the point of that, what did that do for the city?

What was the Brooklyn Museum all about? That wasn’t about...sending us a message about how we should run the city. That was about Rudy Giuliani running for the Senate and trying to appeal to Catholics around the state. And it was like acid rain on the city. We didn’t need one of our most venerable institutions, whatever you think of that show (and I didn’t think much of it), to be threatened with being shut down under what was clearly an affront to civil liberties.

Fred Siegel: Take the Khalid Muhammad thing. The tapes very clearly show Khalid Muhammad’s people throwing the chairs. Giuliani’s unwillingness to apologize for crazies – [his willingness] to cut off Al Sharpton, not take Sharpton seriously -- was one of the reasons he was a successful mayor.

Small Businesses And Patronage

Joan Decamp: I just want to speak about the business interests because Dinkins, who was certainly not a competent mayor, did have a small business office where if you had your own little business you could go and get help. When Giuliani came I don’t know what happened to that place, because I looked for it and I couldn’t find it, and we did need help with stuff. It just seemed as though small businesses were no longer the interest of that administration.

Fred Siegel: The trouble with what you are saying is the Dinkins small business office was mostly a place to put patronage employees; it had nothing to do with small business. What Giuliani did for small business is eliminate a lot of the harassment fines that Bloomberg has brought back.

Rob Polner: On small businesses: Rudy Giuliani was handed his first defeat in the City Council by a coalition of small businesses that opposed his proposal for big box stores that would be up to five football fields in size, about twice what Dinkins had pushed for. This is a city of small businesses once you get outside the Manhattan center and they did not view him as their friend.

It is true, there was a tremendous amount of patronage in Dinkins’ years and Rudy was right to target it rhetorically, but when he became mayor it was patronage galore. Not as soon as he became mayor but as time went on, there was a tremendous problem of patronage across the board. Lots of people who were hired were not qualified, particularly at the agencies that he didn’t particularly care about, the non-law enforcement agencies.

Fred Siegel: The problem of patronage is not going to be eliminated unless there is a competitive politics in the city that provides… accountability, which is very unlikely.

Economic Development Policy

John Tepper Marlin: Mayor Giuliani at a large meeting said that the number one principle in his economic development policy was controlling crime. Do you think that is a fair statement on what he was doing?

Fred Siegel: I think you are absolutely right. He thought crime reduction [was economic development], and I think he was right. It used to be that developers were very chary about many neighborhoods in the city. Now I have developers saying “I can build anywhere in New York,” and I think that’s had a tremendous benefit.

…[On the other hand] Giuliani wanted to sell the [upstate reservoirs] in the first term because, again, the financial control board was coming down his neck. Alan Hevesi was running the comptroller’s office then, and he stopped it, and it was a very good thing that they curbed Giuliani when he wanted to take this foolish move.

What View Of Urban Life Did He Leave NYC?

Gotham Gazette: Mr. Siegel, you mention at the beginning of your book that New York, during the Giuliani years, was a stage for two competing worldviews. To both of you, what view of urban life and the way that a city should be governed do you think Giuliani left New York at the end of his term in 2001?

Fred Siegel: The key point is the notion of governability. [Before, people believed that] New York was the ungovernable city.

Let me get a little wonky for one minute. When Dinkins takes over, beating Koch, the city charter is revised and the old Board of Estimate, which requires logrolling to get anything done, is eliminated. The mayor becomes a much more powerful office. My book was originally much longer and I had many pages on the Board of Estimate. They’re all gone, virtually all gone; the editors said no one in their right mind would read it.

Dinkins never understood the new powers of the mayor over the budget. Giuliani understood them. I once gave him a tutorial on the city charter and I realized he knew more about the charter than I did. He was just looking for any small wrinkles that I could pick up.

To go back to what Rob said at the beginning: In that summer of the 2001 election, three of the four candidates wanted to continue Giuliani’s policies, as did 60 percent of Democrats. Giuliani, himself, was personally unpopular, as he should be, given what he did to his wife, but the sense was the city could be governed and we weren’t going to go back on welfare reform and crime. I think that was his legacy.

The problem is, there was much more to be done. When Bloomberg was asked what he had done for his first 100 days, he said “I prepared for the next 1,000.” He’s still not prepared.

Rob Polner: I agree with Fred that the former mayor did give the city some confidence that it could be governed. I think that was an important message to get across.

I’d like to think the city has matured a bit -- we don’t need a big man or protector to come over the hills and save us. This is a democracy. It’s not a monarchy or an oligarchy. We don’t need a showboat. We don’t need a mayor who has to put himself in the middle, melodramatically, of everything that goes on in this town.

Maybe this had its place for a while, but I think we’re better off without it, and I think Bloomberg, whatever his faults, understands that. He’s not driven by this idea of big personality or the need for constant conflict and contentiousness, and I think the city needed a rest.

Rudy fell down on issues that didn’t really lend themselves to law enforcement, to a big stick, to making a lot of noise. There are a lot of issues like that. He did not try to wean the city off of its heavy dependence on Wall Street. He did not try to develop or seed new sectors. He did not try to safeguard some of the manufacturing jobs, and there aren’t many of them left. And on and on.

We don’t need a big man as mayor, we need a government and public participation, and attention to these kind of nuanced problems that don’t necessarily lend themselves to big headlines. And, in part because the violence and the crime in the city have abated, this is the time to address them.

Related Articles

Giuliani's Legacy: The Second Most Effective Mayor Of The 20th Century, by Kenneth T. Jackson.

Giuliani's Legacy: A Change In The Way New Yorkers Think About Crime, Welfare, Quality Of Life, Squeegee Men, by John Tierney.

Giuliani's Legacy: Taking Credit For Things He Didn't Do, by Wayne Barrett.

(All three articles were written before September 11th, 2001)

Campaign 2005: Civil Rights Issues Divide Bloomberg and Democratic Rivals

There is no civil rights issue in this year's mayoral contest as explosive as the racial killings that decided the 1989 and 1993 elections. And both Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the four Democrats seeking to replace him cultivate public images as supporters of civil rights and civil liberties. But the incumbent does have a different approach to how the power of the city can and should be used to achieve equal rights, going so far as to say that New York was wrong to have used its purchasing power to fight apartheid in South Africa. And the continuing concerns with security do present some disagreements. There are also differences between Bloomberg and his opponents on handling race relations, abortion, same-sex marriage, and other such issues.

Race Relations

Bloomberg has succeeded in reducing the temperature over race relations in the city from the Giuliani era, sometimes in symbolic ways, such as meeting with Giuliani’s nemesis, the Rev. Al Sharpton, and treating former Mayor David Dinkins with respect denied him by his predecessor. He also moved quickly to defuse the latest Howard Beach racial incident, saying the city would not stand for such things.

The Democratic hopefuls have long records of involvement with civil rights issues, but recent stumbles by some have hurt them with voters of color.

Fernando Ferrer, of Puerto Rican ancestry, created political trouble for himself when he told a police group that the cops who shot Amadou Diallo 41 times in 1999 were “over indicted” and did not commit a crime. The officers were found not guilty.

Ferrer, who had gotten himself arrested outside Police Plaza with those demanding indictments in the case in 1999, insists he never changed his view on the case, but that he did misspeak. With endorsements by African American leaders such as former State Comptroller H. Carl McCall and current City Comptroller Bill Thompson, the controversy has subsided somewhat.

But his leading African American rival, Manhattan Borough President C. Virginia Fields, pounced on the issue by saying the police shooting “rises to the level of a crime.” Back in 1999, however, she refused to get arrested outside Police Plaza and referred to the case at a press conference as “an isolated tragedy.”

As for Gifford Miller, Daily News columnist Juan Gonzalez noted recently “Miller was part of the [1999] press conference where Fields made her milquetoast remarks” about the case.

Bloomberg, a private citizen in 1999, took no public stand on the issue.

Fields’ involvement in the civil rights movement goes back to marching as a child with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in her native Alabama. Her latest and most publicized effort to show herself with broad multi-ethnic support became the low-point so far of her campaign. Press reports revealed that a piece of her campaign literature included a doctored photograph, the white supporters who had actually been in the picture replaced by Asian Americans, who told the press they didn't even support her.

Representative Anthony Weiner, the fourth Bloomberg opponent and an otherwise strong civil libertarian, has involved himself in the campaign to rid Columbia of professors he believes to be anti-Jewish and unfair in discussions of Middle East affairs.

City Commission on Human Rights

One area where Bloomberg has a mixed record is restoring the City's Human Rights Commission. The Giuliani administration reduced the agency's budget by more than 75 percent, then perversely passed an amendment to the City Charter making it a charter agency that could not be dissolved without another amendment.

While Bloomberg made an initial move toward increasing its budget and installed more competent people to staff it, the agency continues to have a low public profile and budget.

The administration is also opposing passage of the Local Civil Rights Restoration Act in the City Council that supporters say would strengthen the existing law. If Miller follows through on his promise to get that bill passed soon, yet another confrontation with the mayor over civil rights would be set up during this campaign year.

Civil Liberties and Public Safety

In the wake of the London underground bombings, Bloomberg ordered random searches of the bags of people using public transportation here. It was condemned by conservatives as useless unless some sort of profiling was employed. The New York Civil Liberties Union raised concerns that the searching is "virtually certain neither to catch any person trying to carry explosives into the subway nor to deter such an effort" and argued that riders have been selected in a "discriminatory and arbitrary" manner.

Most of the public, shaken by what happened in London, is not raising objections to the searches.

In a July 28 mayoral race debate that Bloomberg did not attend, the Democrats attacked his approach. While not ruling out bag searches, Ferrer called it "'ridiculous as the centerpiece of an antiterrorism strategy," and proposed things such as more surveillance cameras, and more cops on transit.

Fields did criticize the bag searches, saying she had heard it would soon be discontinued, a fact disputed by the City Police Department.

Pro-Choice

Mayor Bloomberg, like his Democratic rivals, is a staunch advocate of a women's right to choose and has contributed personally over the years to abortion rights groups. The Abortion Rights Action League New York Pro-Choice , which endorsed Democrat Mark Green over Bloomberg in 2001, this time went for Bloomberg, especially praising his executive order requiring the training of resident doctors in abortion procedures, unless they have moral objections.

Fernando Ferrer attacked the abortion rights group for their endorsement, citing Bloomberg's personal financial support for a host of anti-choice politicians from President George W. Bush to Alabama Senator Richard Shelby.

Party Affiliation Becomes An Issue

Indeed, Bloomberg's role as the largest individual donor to the Republican Party in the nation -- he wrote a $7 million personal check to help underwrite the party's convention in New York -- is an issue for many civil liberties groups as the Republican-controlled White House and Congress renew the Patriot Act, limit abortion rights, try to pass a constitutional amendment against same-sex marriage, and promote conservative John G. Roberts for the United States Supreme Court.

Bloomberg went so far as to distance himself from the Roberts' nomination saying that if the judge would not state his position on Roe v. Wade, then he would oppose his confirmation.

Using the City's Purchasing and Shareholder Power to Advance Civil Rights

For decades, the city government has used its contracting process to move social agendas. In the 1980s, it prohibited its contractors from doing business with South Africa's apartheid regime, nor with Northern Ireland unless the companies there complied with the McBride Principles that certified a commitment to treating the Catholic minority fairly.

Bloomberg has gone along with some of these contracting laws, signing the Living Wage bill that requires some classes of contractors to pay substantially more than minimum wage. But he drew the line at the City Council's Equal Benefits Law that requires contractors that offer benefits to the spouses of their employees to extend the same package to the domestic partners of workers.

Bloomberg vetoed the Equal Benefits Law, and when his veto over overturned, he began pursuing legal action in state court to prevent its implementation, saying it is illegal to require contractors to do anything more than provide the best service at the best price.

In June, Bloomberg was asked whether it was illegal for the city to have banned contractors from doing business with apartheid South Africa. While he said the city should not have done business with the apartheid regime, "the contracting process should never be used to advance social causes." Miller called Bloomberg's position on how to deal with apartheid "outrageous."

Bloomberg also criticized City Comptroller Bill Thompson and his own Finance Department for pushing shareholder resolutions to advance reform in the corporate world, but neither Thompson nor Finance Commissioner Martha Stark has discontinued the practice.

Bullying in Schools

Bloomberg vetoed the Dignity in All Schools Act, an anti-bullying measure, and is refusing to implement it, saying that the Council had no legal right to dictate to his Education Department on such policies. His Democratic rivals are all strong supporters of the measure.

The Dignity law has prompted the Education Department to take more steps toward documenting and reducing bullying, but not all the ones specified in the law. Bloomberg, like his Democratic opponents, supports a state version of the law which has been held up in the Republican-controlled Senate. Given his control over city schools, he has yet to say why he has not simply ordered the department to implement the provisions of the bill.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Rights

Bloomberg is referred to commonly as a "pro-gay" Republican, but he has been so resistant to the issues pushed by New York's lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender movement that the leading political group, the Empire State Pride Agenda endorsed one of his opponents, Gifford Miller, in June, an unusual step for the group. Bloomberg is supported by the gay Log Cabin Republican chapter, but all of the Democratic clubs are vigorously supporting his opponents.

Bloomberg ran in 2001 on a platform of supporting major gay initiatives, but despite his "promises kept" campaign theme, this is one area where even he acknowledges that he has backtracked. In 2002, he did fulfill a promise to sign a bill banning discrimination on the basis of gender identity and expression, covering people of transgender experience. But since then, he has vetoed and opposed in court the two bills that he had supported as a candidate, one dealing with school bullying and the other with requiring contractors to provide domestic partner benefits.

All of the Democratic hopefuls strongly support the right of same-sex couples to marry, some like Miller pledging to start performing them on January 1 if elected.

Bloomberg has a record of avoiding the issue, making vague statements in the past about the government having no right to tell anyone who you should marry, but not supporting the gay marriage movement. He did oppose President Bush's push for a federal constitutional amendment banning it.

When, in response to a lawsuit, State Supreme Court Justice Doris Ling Cohan ruled this March that New York City has to begin issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, Bloomberg appealed the decision, but declared himself in favor of the right to marry. He said that he had "no choice" but to appeal the ruling. Representative Barney Frank , an out gay Democrat from Massachusetts, publicly attacked Bloomberg's legal appeal of the ruling, calling it "terrible for us."

"The best way to win same-sex marriage-through the courts and politically-is when you're defending a reality," Frank said. "That's where Bloomberg undermined us."

All of the Democrats say they would drop Bloomberg’s appeal of the decision so that the city could open its marriage bureau to same-sex couples.

Andy Humm, a former member of the City Commission on Human Rights, has been in charge of the civil rights topic page since its inception in 2001. He is co-host of the weekly "Gay USA" on Manhattan Neighborhood Network (34 on Time-Warner; 107 on RCN) on Thursdays at 11 PM. Â

Interpreters at Poll Sites

It was Tuesday morning in 1992 when I accompanied my newly naturalized mother to the polls on Election Day. She had not wanted to vote since she was unaccustomed to the tradition and process of electing a representative and she was not exactly fluent in English. So at the tender age of ten, I offered to go with her. At the polling site, although I provided limited assistance, my presence made her feel more comfortable. But it is this same fear and intimidation that prevents the rest of my family, my aunts and uncles, from heading to the polls on Election Day-- in essence disenfranchising them.

Every fall millions of voters, such as my mom, brave the intimidations and frustrations of voting to cast a ballot. Here in New York City, about twenty-five percent of voters need language assistance. But that’s no surprise in NYC, a bastion of ethnic diversity. What is alarming is the lack of assistance provided to these citizens who wish to vote.

Congress initially addressed the needs of language minority citizens to access the polls in 1975 when it amended the Voting Rights Act. The Section 203 amendment established a formula to determine jurisdictions that must provide materials, instructions, and assistance relating to the electoral process in the applicable minority language, in addition to English.