A queen and three prime ministers descended on Singapore last week to lobby the International Olympic Committee on behalf of New York’s rivals to play host to the 2012 Olympics. President George W. Bush did not go, appearing only briefly in a video, and neither did any other Bush administration officials.

A queen and three prime ministers descended on Singapore last week to lobby the International Olympic Committee on behalf of New York’s rivals to play host to the 2012 Olympics. President George W. Bush did not go, appearing only briefly in a video, and neither did any other Bush administration officials.

Indeed, of the five cities competing for the prize, only New York did not have the obvious and vigorous backing of the nation it represented.

To many New Yorkers, Washington’s inattention was typical – symbolic, in its own small way, of a lack of federal support for the city that has been evident for at least a generation.

Such federal indifference is one reason why progress has been so slow on a range of local issues, whether rebuilding Ground Zero or housing newcomers. It helps explain New York’s inability to finish numerous transportation projects important to the city and the region -- the Moynihan Station, which is supposed to replace Penn Station by converting the post office across the street; the Second Avenue subway, which has been planned for decades (some tunnels for it were built in the 1960's); the East Side Access Project that would create a direct link between the Long Island Railroad and Grand Central Terminal.

This was not the way things used to be. Federal aid during the New Deal built familiar landmarks like the Triborough Bridge and LaGuardia Airport, and created the city’s network of neighborhood parks. Massive flows of federal money for housing in the post-war years resulted in the row after row of hulking, unadorned apartment buildings that rise along the eastern edge of Manhattan or stand beside the Rockaway surf.

By contrast, in the tradition of the Daily News headline, “Ford To City: Drop Dead!”, Republicans in Congress last year tried to rescind money allocated to Moynihan Station.

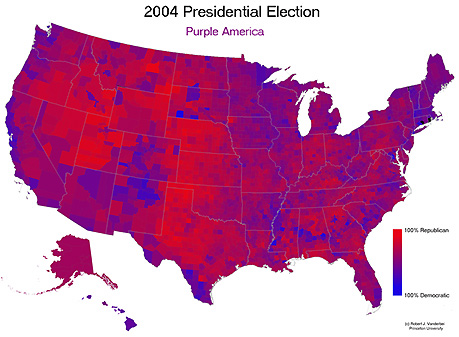

Many consider a tilt against New York inevitable, given that electoral college map that was shown over and over during last year’s election, with its sea of red surrounding the blue islands like New York. Some New Yorkers believe they are simply on the wrong side of a majority with an anti-cosmopolitan attitude and an anti-urban agenda.

But the truth, as we see it, is more nuanced, and more hopeful.

Granted, New Yorkers like to view themselves as unique and apart, connected to the United States only by the tiniest landmass at the northern end of the Bronx. But, in truth, New York remains very much linked to the larger tri-state region that includes New Jersey and Connecticut. The New York area’s jam-packed bridges and tunnels testify to this. Commuters to Manhattan supported approximately $70 billion of New York City’s economic output in 2000, according to the Regional Plan Association, while, for its part, New York City generates more than 40 percent of the region’s wages. Surely these interconnections can trump division in times of need.

At the same time, there has emerged an archipelago of huge, fast-growing “super-regions” across the nation that are coming to resemble (at least a little) the New York urban region in terms of sheer size and diversity and infrastructure needs. They have given New York a larger set of super-sized cousins -- and potential allies.

FORGING LINKS

How might New York prevail?

We suggest two ways to transcend the balkanized local politics of authorities and mayors on the one hand, and the seemingly inhospitable calculus of the red-blue map on the other.

Look To The States

First, New York and tri-state residents should look much more than they have to the tri-state capitals -- Albany, Trenton, and Hartford -- to collaborate to meet their needs.

This is already starting to happen. Concern for the future of Amtrak, for example, has already drawn state leaders from across the tri-state region into successful common cause. The need to protect air quality and watersheds has enlisted all three states’ attorneys general in a nine-state lawsuit challenging Bush administration regulations that exempt coal-fired power plants from tough controls on mercury pollution. And in the wake of the London terror attacks last week, Governor M. Jodi Rell announced that Connecticut had joined New York Governor George E. Pataki and New Jersey Governor Richard J. Codey in a tri-state agreement allowing troopers from each state patrol onto the commuter trains into New York City, retaining their arrest powers.

True, the slow progress of projects like the Trans Hudson Tunnel or the Cross Harbor Rail Freight Tunnel (whatever one thinks of those proposals) underscores how frequently regional initiatives fall victim to either the horse trading of Albany (or Hartford or Trenton) or bickering between the states.

But on many issues the states matter far more to the health and prosperity of their metropolitan areas than Washington does. This is why New Yorkers should insist that multi-state collaboration widen to address such common priorities as federal and non-federal housing policy; the defense of critical worker benefits like the earned income tax credit (EITC); and the region’s fundamental infrastructure.

Imagine the creation of a regional, multi-state pool of capital dedicated to the preservation and modernization of the infrastructure--airports, ports, passenger rail, roads, bridges.

Or consider the founding of a new multi-state fund dedicated to the remediation and reclamation of polluted land along shared waterfronts.

Or picture the establishment of a new regional, multi-state pool of worker training funds to prepare workers for a knowledge economy that has no respect for political or administrative borders.

Where would the new funds come from? They could come from a regional armistice on tax abatements and other government subsidies used to lure companies and firms from one side of the region to the other. Or perhaps the three states (with similarly motivated allies out West or in the South) should pile onto Felix Rohatyn’s recent proposal of a $100 billion federal trust fund, to be financed by special 50-year Treasury bonds, to finance high-priority state and local investment programs, including physical infrastructure.

In this way the region would take the lead in pressing for the restoration of the traditional federal-state commitment to investing in the physical and intellectual infrastructure of America’s regions.

Look To Emerging Super-Regions

But intra-regional collaboration, as important as it is, can only go so far. Beyond it, the tri-state area needs to look outward, and locate common ground with other urban super-regions of the country in ways that confound popular perceptions of the political divide.

This, too, has already happened, to some extent, with the blunting of Bush administration efforts to defund Amtrak by a bipartisan confederation of Northeastern, Midwestern, and Californian representatives in the House last month.

But the opportunity is larger. The titanic demographic and development changes sweeping the nation are creating massive “new” regions of shared interest. Scholars have identified from eight to 10 huge “megalopolises” (in pdf format), gargantuan region-scaled growth zones organized around major interstate highways, across the country. These include, for example:

- The Phoenix metroplex

- the I-35 corridor in Texas that encompasses a string of metropolitan areas running from San Antonio in the South through Dallas to Kansas City in the North

- Greater Atlanta and the Piedmont region

- The Colorado Front Range

- Houston, New Orleans, and the Gulf Coast

Such mega-regions now encompass more than 70 percent of the country’s population and extend into 35 states. They will add seven of every 10 new Americans by 2040, and three-quarters of the capital to be expended nationally on private real estate by then. They went for John Kerry over George W. Bush (by 51.6 percent to 48.4 percent) in 2004.

As such these newer conurbations represent a huge opportunity for alliance-building, in Congress or on other fronts, whether on highway construction, workforce development, transit, or port and security activities.

Shared Interests Among Super-Regions

Look at immigration patterns. The immigrant gateways (in pdf format) of the past 20 years include traditional places like New York City, Chicago and Los Angeles but also newer places like Charlotte, Atlanta, Houston and Phoenix. This last may help explain why Arizona’s congressional delegation is the driving force behind a sensible “temporary worker” proposal that (unlike President Bush’s version) would allow New York’s many undocumented immigrants to keep working on three-year permits and enjoy other rights, while also providing them a clear path toward a green card.

Or take infrastructure needs, particularly the interest in mass transit. The newer, fast growing cities of the Sun Belt are having the same kinds of discussions around cores and corridors that the New York metropolis had 80 years ago. Colorado may have voted for Bush 52 to 47 percent in the last election, but during that same election, voters in the Denver metropolitan region overwhelmingly passed (58 to 42 percent) a referendum to raise $4.1 billion for a 118-mile light rail system. (Significantly, four counties that voted against Kerry supported the transit system.)

Or even take social policy. Our analysis of residential patterns of low-wage workers in the country shows an incredible confluence between the densely populated cities of the Northeast and Midwest and rural areas in the South. Listening to the political class, one would never realize that constituents of legislators in Mississippi have as high a stake in the policies that make work pay -- the Earned Income Tax Credit, child care, and health care coverage -- as residents of New York City, Newark, and Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Or consider the needs of urban counties. America contains some 64 older suburban or “first suburban” counties -- denser, longer-established suburbs (often in the Northeast) that now face truly urban challenges yet which frequently reside in a policy blind-spot because they are neither poor enough to qualify for most federal urban programs nor new enough to tap federal and state programs that focus on building new housing and infrastructure. Predictably, this slice of America contains such familiar places as Nassau County in Long Island, Essex and Hudson counties in New Jersey, and Fairfield County in Connecticut.

But dozens of these “urban” first suburbs now dot the rest of America, where Fulton County surrounding Atlanta, Harris adjacent to Houston, Los Angeles County and Dade County, Florida all stand as fellow “first suburban” communities.

What is more, these 64 counties now house over 52 million people and comprise nearly 20 percent of the American population. That means that close to 50 percent of the American population -- almost a majority of Americans -- live in traditional central cities and five dozen or so urban counties.

Clearly, metropolitan New York does not stand alone in facing large urban challenges. A growing swath of America now shares a common agenda around infrastructure, social policy, and competitiveness writ large. Phoenix and Dallas may soon rank almost as important as Albany, Trenton, and Hartford in what needs to become a canny new regional strategy for prevailing in an unfriendly political moment.

Redrawing the Map

It’s becoming clear that while the red-blue map depicts an unfavorable Washington politics, it tells only part of the truth.

More accurate, particularly as the new mega-regions grow and urbanize over vast multi-county landscapes, is the so-called “purple map” produced by Robert Vanderbrei of Princeton University which shows, at the metropolitan or local scale, that far more of America consists of evenly split than sharply red or blue districts.

On this map, competitiveness, not one-party domination, is the norm. Metropolitan areas and mega-regions -- with their more favorable political priorities and infrastructure needs -- spread wider and wider and hold out opportunity.

And so Senator Charles Schumer was exactly right when he bemoaned the onset of a “culture of inertia” in Albany and New York recently. But beyond just parochialism and gridlock, New Yorkers are indulging in something much worse -- pessimism. That must change, if one of the world’s great megalopolises is to respond to the challenges being mounted by urban regions around the world, as they spend billions on new rail spines, economic development, and urban regeneration.

Instead of bemoaning the red-blue map, shouldn’t the New York region simply redraw it? By collaborating across state borders and finding common-cause with the nation’s other mega-regions, the New York super-region ought to be able to forge a new and powerful super-alignment that could actually transform current politics.

Bruce Katz is director and Mark Muro policy director of the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution.

Related Articles

NY's Concerns Can Be of National Concern Once Again By Ester Fuchs