Voting Rights Revisited

When earlier this month thousands of immigrants and their supporters rallied throughout the streets of lower Manhattan, many were carrying signs that said “Today We March, Tomorrow We Vote.”

For those old enough to remember, or attentive enough to history, the sentiment expressed in those signs recalled events decades old, largely in the rural South, that led up to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But the Voting Rights Act has more connection to the recent marchers than just sentiment. Some provisions in it continue to affect parts of New York City directly. And, set to expire in 2007, they are being debated by some of the same people who are arguing over immigration.

The Voting Rights of 1965

On March 7, 1965 state troopers attacked and beat marchers in Selma, Alabama, en route to the state capitol in Montgomery. The marchers were demanding a repeal of poll taxes, literacy tests and grandfather clauses – all forces that effectively denied them their right to vote under the fifteenth amendment -— when they were met by law enforcement officers also intent on denying them their constitutional right to peaceful protest protected by the first amendment.

The attention this received and the persistence of the movement for voting rights, convinced President Lyndon B. Johnson and the U.S. Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. At the time of passage President Johnson proclaimed: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes."

While initially intended to address discriminatory voting practices that targeted African American voters, the scope and impact of the legislation has been much wider. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, and subsequent amendments, have been instrumental in blocking discriminatory practices of elections administrators and ensuring greater participation and representation for language and racial minority voters.

Sounding the death knell for literacy tests and grandfather clauses the act applied a nationwide prohibition against the denial or abridgment of the right to vote on the basis of race, color, or membership in specified language minority groups (Section 2).

From its inception, the act also prevented specified jurisdictions from making changes to their election systems without receiving “pre-clearance” from the federal government. This section, commonly referred to as Section 5 is distinct in that it is geographically specific, containing special enforcement provisions targeted at those areas of the country where Congress believed the potential for discrimination to be the greatest.

While all of Alabama, Georgia and several other states are covered, so is much of New York City, specifically the Bronx, Brooklyn and Manhattan.

One other major element of the Voting Rights Act was added in 1975 after the case had been made that voting discrimination had been suffered by Hispanic, Asian and Native American citizens even after passage of the Act 10 years earlier. Section 203 added protections from voting discrimination for language minority citizens by requiring political jurisdictions with populations of minority language voters that reached a certain size of the electorate to provide bilingual written materials and other assistance.

The Voting Rights Act in New York City

In New York City, the primary elections of 1981 were abruptly halted two days before Election Day as the courts found that the city not only failed to get pre-clearance of their newly drawn city council lines, but that the lines were drawn in a manner that would have diluted the Latino/Latina voting bloc. State Senator Carl Andrews, a former council member and original plaintiff in the lawsuit, believes it was a watershed moment in New York City’s election history: “The front page of the New York Times read â€Election Cancelled.’ People took notice…and we did away with the old system.” As a direct consequence the city’s Board of Estimate was dissolved and the city was compelled to expand from 35 to 51 members of the City Council and a redrawing of district lines to increase minority representation on the council. This ushered in greater numbers of African American and Latino council members and the city’s first ever Asian Pacific American legislator, John Liu, in 2001.

Under the Voting Rights Act, the Bronx, Manhattan and Brooklyn have been required to provide all registration and voting material in Spanish as well as English since 1975. Coverage of Chinese was applied for the first time in all three boroughs in 1992 at the same time that coverage for Spanish was extended to Queens. After the 2000 census it is now required that elections materials be available in Korean in Queens.

In testimony to Congress, Margaret Fung of the Asian American Legal Defense Fund (AALDEF) , a civil rights organization based in New York City that for 31 years has promoted and protected the rights of Asian Americans, proclaimed the voting rights act (specifically Section 203) a success story. “Section 203 has removed barriers to voting and opened up the political process to thousands of Asian Americans, many of them first-time voters and new citizens,” Fung said. “It has also aided grass-roots efforts to increase voter registration among Asian Americans.” However, according to voting rights groups the Voting Rights Act has not always lived up to its potential. AALDEF is quick to point out that language materials in Spanish, Chinese and Korean, while required at certain polling sites, are often not available on Election Day. The group also argues that with so many immigrant groups and different languages spoken in New York City, many people are not protected by the Voting Rights Act and thus ballot materials are not provided in their language.

The Future of the Act

Last year marked the 40th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act and the beginning of debate over the reauthorization of the temporary provisions that expire in 2007. While groups like AALDEF, the League of Women Voters and the ACLU have joined together in a campaign effort to “Renew the VRA” there is vocal opposition to it reauthorization, or at least to parts of it.

Representative Peter King from Long Island, sponsor of the controversial immigrant criminalization bill HR 4437, has lead an effort in Congress to block renewal of the language assistance provisions of the Voting Rights Act. Fifty-six members of the U.S. House recently signed a letter circulated by King of New York and Steve King of Iowa urging House Judiciary Committee Chairman James Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin (the other lead sponsor of HR 4437), to fight against the renewal of Section 203. The letter argues (in pdf format) that multilingual ballots "divide our country, increase the risk of voter error and fraud, and burden local taxpayers." The letter cites a November 2005 Los Angeles Times article that reported Los Angeles County had spent more than $2.1 million to provide interpreters and multi-language ballots for the 2004 election and it states that in 1996, one county in California had to spend $30,000 on Spanish ballots when only one resident requested Spanish materials.

The representatives also wrote that "federal law protects the right of all citizens to bring an interpreter into the voting booth with them if they have difficulty understanding a ballot written in English." According to King and others, that practice is "the right approach." Glenn Magpantay, staff attorney with AALDEF believes the financial argument against the multilingual provisions of the voting rights act is just a smokescreen. “It’s basically just a misguided nativist argument,” states Magpantay. “This provision allows more Americans to vote.” AALDEF is actually advocating for various measures to make it even easier to get language assistance at the polls.

We may see a debate in the coming months over Section 5 pre-clearance as well. While the pre-clearance has helped protect the rights of those in the specified jurisdictions, some argue it has outlived its usefulness, and should be allowed to expire. Others argue it should be expanded to a national level.

Doug Israel is policy director at Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham GazetteÂ

How To Make It In NYC As An Artist

It is still possible to thrive as an artist in New York City, according to several recent reports, conferences and hearings, as long as artists follow some simple guidelines.

1. Never Get Sick

A recent survey of independent artists in the city (those without a steady employer) entitled Creative Workers Count found that more than a third "experienced a significant gap in health insurance coverage in the last year," and that 75 percent of those without insurance put off seeking needed medical care. The report, which is subtitled "New York City's Arts Funding Overlooks Individual Artists' Needs," found that many artists also lack retirement plans, and "are coping with financial instability generated by erratic employment and low incomes."

2. Don't Be Born Abroad

This month, the cellist Yo-Yo Ma testified before Congress about the "extraordinarily high" barriers to foreign artists. He was talking in particular about the trouble foreign artists have been having in getting temporary visas to visit the United States in order to perform. But a few weeks earlier, Randall Boursheidt of the Alliance for the Arts testified before the New York City Council's committee on cultural affairs about the lack of opportunities for the city's immigrant "artists, both old and young…to continue to develop their work."

3. Lower Expectations

At the Creative New York Conference held earlier this month at the Museum of Modern Art, dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones contrasted what it was like in 1982 when he started his company in New York with what it is like now for dancers: “Five of my former dancers…are really depressed…they are despairing.” Two decades ago, “dancers would work for a song. Dancers did not expect health insurance, life insurance, they did not expect to have middle-class lives. Now everybody does.” That doesn’t mean they get it.

4. Make Sacrifices

At that same conference, Glenn Lowry, the director of the Museum of Modern Art, explained that artists are “willing to give up a great deal of comfort – financial, emotional, maybe psychological” to be in New York City. (But “what keeps me up at night” is that these artists will be “just as at home in Shanghai as they are in New York, if that becomes a more attractive city for their practice.”)

5. Learn To Love Inadequate, Overpriced Spaces

Those who care about the arts in New York City are increasingly alarmed at the trouble artists have in finding places to live and spaces to work – whether for rehearsing, exhibiting or performing (see Space Woes).

As bad as the problem is, what’s worse is that nobody really knows how bad the problem is, according to Boursheidt’s City Hall testimony: Nobody knows where the artists live, and how many are being forced to leave. By the time artists "exist in sufficient numbers in neighborhoods like Soho or Williamsburg or the South Bronx for the rest of the city to notice," Boursheidt said, "it's a pretty good sign the development pressure has already begun to force them out of those neighborhoods."

6. Focus On Business and Politics

There are opportunities for funding and other support from corporations, non-profit organizations and government agencies for those talented enough, and savvy enough, to make the cut. The private non-profit New York Foundation for the Arts, for example, famously offers annual "fellowships"($7,000 in cash) to about 150 individual artists in 16 categories from painting to performance art, crafts to composition. The official cultural councils of all five boroughs in the city offer grants as well, and, along with the Department of Cultural Affairs, provide other services, such as artist registries to aid individual artists in getting gigs.

But none of the cultural czars pretend there is enough funding to go around, the emphasis is support for non-profit arts organizations rather than individual artists, and there are such complicated restrictions and requirements for most grants and fellowships that an industry has grown up just to sort it all out.

"Artists need to be able to have the time to think about their art and to create," Ella Weiss of the Brooklyn Arts Council testified at the City Council hearing. "They also need to know that our society values the time they spend [creating.] The National Science Foundation funds pure research. Do we really ever fund pure art, just for the arts sake?"

"The secret shame of the art support system -- public and private funds -- is how much it talks about artists, but how little it really does to meet their needs directly," testified Ted Berger, the executive director of New York Creates, which tries to help folk and craft artists.

“An artist’s business is basically his or her art,” noted Councilmember Domenic Recchia, the chairman of the cultural affairs committee, yet “they can’t get a small business loan from the Small Business Administration.”

“There are far too many arts organizations in New York City right now,” Tom Healy of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council testified. “They don’t do the best things for the artists they try to serve.”

7. Be Perfect

A composer who teaches on the faculty of the Juilliard School observed in a television documentary marking its centennial celebration that an average graduate of law school or medical school can still have a decent career. But it is not possible, he said, for a successful artist to be only average.

8. Have Hope

Yes, there are challenges, but some smart people are trying to address them.

Health care is a problem, for example, but an innovative approach to it is suggested by a program at Brooklyn’s Woodhull Hospital, called Artists Access, in which an uninsured dancer can perform in the pediatric wing for an hour a week, or an uninsured painter can offer patients drawing lessons, in exchange for “health care credits” they can redeem when needed.

Immigrant artists are being neglected, but the Brooklyn Arts Council has made a small step towards aiding such artists through its Folk Arts program, in which it has located about 135 traditional dancers from the borough, and then matched them up with schools, senior centers and other place where they can perform.

As New York City Cultural Affairs Commissioner Kate Levin said at the opening of the Creative New York Conference, “for several generations now, New York City has provided an environment where creativity flourishes, often against all odds -- and indeed, sometimes because of those odds. This is no small feat…Creativity can be enormously robust and productive, but an individual’s vision or idea can be quite fragile. Often, we think of creative people as craving solitude, but the reason they’ve flocked to New York for so many years is because of the critical mass of individuals, institutions and opportunities.”

Â

Harlem's Heyday

The following is an edited transcript of a meeting of the Gotham Gazette Book Club on March 29 with guest Kevin Baker, author of Strivers Row.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Kevin Baker is back for the third time to round off our discussion of his history of New York City by novel. We've discussed Paradise Alley, which takes place in the draft riots of the 1860s; Dreamland, which takes place during the large scale Jewish immigration during the early 1900s; and now Strivers Row, which takes place in Harlem during the second World War.

THE HISTORY OF HARLEM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How much of the Harlem that you write about is still left?

KEVIN BAKER: Thanks for having me. Not that much is actually left physically of that Harlem. The great dancehalls – the Savoy, the Cotton Club – are all gone. Small's Paradise, a great club where Malcolm X used to hang out as a young man that figures prominently in the book, that's now an I-Hop. A lot of those things have kind of vanished.

Strivers Row – the book's namesake – is still there. It's located on 38 and 139th streets – still two of the most beautiful streets in the city.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How much of the mood or spirit is left?

KEVIN BAKER: Some of it is still there. There's still a lot of vibrancy in the community, even if it's no longer a place that really thinks of itself as the cultural capital of Black America.

By the time I'm writing the book – 1943 – the Harlem Renaissance has already been crushed by the Depression. A lot of those earlier dreams – that the black community was going to come to equal terms with whites – had already been disillusioned. But it was still a place of incredible creativity. It was still a place with amazing music coming out.

One reason that it has changed so much is that Harlem was a ghetto. That's a term we use interchangeably with "slum", but there really is a difference. A ghetto is a place where all members of a certain religion or race are forced to live – whether they're Jewish or, in this case, black. That meant that everyone lived together. At Strivers Row you had not only doctors, lawyers, ministers, but also great musicians, composers – Hubie Blake lived there, WC Handy – prizefighters, all sorts of people. Anybody who made money in the community. That feeling is kind of gone now. There's less of a black elite there.

These are the ways that cities changed. It was a good thing that New York changed – people aren't kept in this ghetto anymore – but of course something is always lost when communities change.

Harlem is still changing and probably will change for good. What this will mean, I don't know. It will probably mean some good things – money coming in. It will probably also mean some people being forced out, which isn't so good.

It will probably be much less black than it has been.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: You wrote in an article in the New York Times that Harlem was a fluke. Can you explain what you meant by that?

KEVIN BAKER: Harlem was planned for this white elite – and that's the natural place for wealthy suburbs: on the periphery of the city.

It had been this sleepy Dutch and then Irish and other white ethnic village for years. Various parts were known as Goatville or Pigville, for the different animals that would run free in the streets. So it was made first into a snappier upper middle class white neighborhood, and was then being set up to be this blockbuster white elite neighborhood. But it was being developed too fast; people weren't moving up there that fast. Developers looked around and panicked.

At the same time, African Americans were coming all the way north. They had lived in a distinctive community since the Civil War Draft Riots, basically for their own protection as much as anything else.

Developers knew they could charge black people two or three times what they charge whites in the city, because the black people had very little choice about where to live. Between 1915 and the First World War Harlem was really established.

NYC: BATTLEGROUND FOR FREEDOM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Your trilogy discusses three distinct eras in New York City history. Why these three eras as a way to explore the city's history?

KEVIN BAKER: Manhattan particularly and New York in general has always been the most contested ground in America. From the slave rebellion of 1712, the supposed slave rebellion of 1741, the many riots of the 19th century, the draft riots, to the labor struggles, and movements for women's rights, civil rights, and gay rights, all these things were really fought out here as much as anywhere in the country.

The three eras I write about were crucial moments in New York City's – and therefore America's – history. Outsider groups forced their way into what was very white Anglo society that didn't really want them here except in a completely subservient position:

The Civil War was a crucible for Irish Americans who came here because of the potato famine, as I describe in Paradise Alley. They started this Draft Riot, opposing a draft into the Civil War. It was horrible; it featured many lynchings and horrible killings of black people in the streets of the city. But it was also put down in large part by Irish police and the military. This was their decision to be part of America – and being an American citizen might mean shooting your friends and neighbors in the street.

With Dreamland, it's the uprising of the 20,000 – the garment workers and the Jewish American experience. This to me was much more about calling America on its promises. The political machinery of the city had a certain democratic feature to it, but was run as this closed Irish clan – you could get everything as a favor but nothing as a right. And here were Jews very idealistically saying "No, this is what America promises and you have to deliver on this." This led to this huge garment strike and then, after that, the tragic events of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, which is the central event of Dreamland (and which we just passed the 95th anniversary of). This would change New York and America forever.

In Strivers Row you have African Americans, who aren't immigrants as we usually think of the term – they'd been here in New York as early as the Dutch. But they are far and away the most outsider group, and this is them forcing their way into the American democracy – whether other people liked it or not.

So it's these three groups and the three folkways they pursued towards getting equal rights. These are the great stories of our democracy. So much of our culture came from Jews, Blacks and the Irish. These are hard stories; they are more brutal stories than we are generally told. But they are great stories and I've tried to capture them.

WRITING HISTORICAL FICTION

BARBARA HIGGENBOTHAM: How you do your research?

BARBARA HIGGENBOTHAM: How you do your research?

KEVIN BAKER: I did most of the research for Strivers Row at the Schomburg Center, which is a fantastic, underused research center in Harlem. I went to many of the great black writers of the time. I also did a lot of reading of the Amsterdam News at the time, which was then as now the leading weekly in Harlem. Terrific paper then, and had some great stuff particularly from a guy named Dan Burley. He was covering everything – politics, entertainment, sports, and great little mood scenes in Harlem, jotting down every word he heard, all this great slang in Harlem in the early 1940s. You can't go wrong with these sources.

With Dreamland, a lot of the terrific Jewish writers of the age helped. Haunch, Paunch and Jowl; and Michael Gold's Jews Without Money. Leon Stein's the Triangle Fire. Triangle, by David Van Drehle, came out after I wrote the book. It's fantastic.

Mostly, I used secondary sources in the books. I'm not writing history here.

I know EL Doctorow likes to say, apparently, do as little research as you can get away with. Certainly Doctorow does this better than any of us, so there's that to be said too. I like to dig in as much research as I can find. It's the little things that tell you so much – the stuff you weren't expecting to find.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: It's great that you mention those books, some of which have been previous selections in this book club, and you can read the transcripts online.

Doctorow was also a guest here, actually. He said that "history written by historians is clearly insufficient", and that novelists also have an important part to play. " The important thing is that over the years there's a consensus about literature," he said. "Some of it makes it and most of it doesn't. The books that make it have, in some way, struck people as somehow true."

KEVIN BAKER: I think that's a very good point. Whether you're writing fiction or not, truth is what you're going for. Does this ring true? The novelist is interested in truth as much as the nonfiction writer. The novelist is looking for what is true in terms of how people act and how the world of human emotions works.

JAYNA GOODMAN: Don't you think that the history that you are going back and looking at can be made up to an extent? History oftentimes is written from oral history that has been passed from generation to generation. People naturally like to exaggerate in their storytelling, so history that wasn't necessarily documented at that very moment is already an extension of the truth.

KEVIN BAKER: One of the things that labeling it fiction enables you to do is speculate more – to kind of indulge.

RACE

GOTHAM GAZETTE: One of the differences between this novel and the others in the series is that while today there isn't that much of a controversy about Tammany politics or European immigration of past eras, racial issues are still a flashpoint. Did you approach this subject differently than the subject of your past books?

KEVIN BAKER: Obviously it's something you're aware of. Race has been this undercurrent of American life for 400 years. There's no getting around it. You'd be in denial to say you're not conscious of it. But I think it is something that does not get better by being left alone. I think it's only going to be through exploring it – through fiction, through nonfiction – that we attempt to make it better. And this is a very sympathetic portrayal of the Harlem community.

Maybe it's audacious to take on the topic, but all writing is an act of audacity. I think in some ways I'm as unqualified to write about Harlem as I was to write about Jewish immigrants and Irish immigrants. I was completely ignorant of all three.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: So it sounds like you don't think there's any sense of in-authenticity about a white author writing about the black experience.

KEVIN BAKER: No. It sounds clichéd to say it, but I think there is a basic humanity that connects us. In some ways, I think it's no more audacious than a male writer writing about a woman. All writing is this attempt to put yourself into different lives, different eras. If we don't attempt that, then writing will be this very shrunken, disfigured thing.

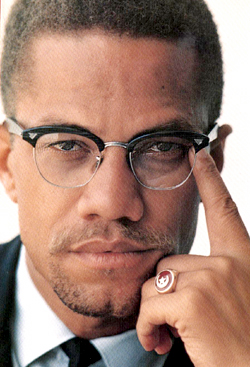

You draw upon things in your life. Malcolm X [one of the two main characters of Strivers Row] had this horrendous childhood, this very hard life. I can't say I know exactly what it's like to go through that in America. On the other hand, I was fairly poor growing up, we were off and on welfare, public assistance, and you get a little bit of a sense from that to know what it's like to be poor – to be an outsider. Again, not to the level that Malcolm experienced. But that is something you draw on.

MARTHA SOFFER: Did you get any negative feedback from the Afro-American community?

KEVIN BAKER: No, I haven't gotten any negative feedback. In fact, I have gotten more African American audience members than ever before – and glad for it. The emotion has been curiosity for the book. The worst response I got was from a white reviewer who thought I was unfair to the Irish. I'm mostly Irish myself. What can I say?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why did you decide to pick Malcolm X as the main character, someone who people know so much about, instead of picking a fictional young man who goes to Harlem, especially since what you write about happens before Malcolm X really becomes a public figure?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why did you decide to pick Malcolm X as the main character, someone who people know so much about, instead of picking a fictional young man who goes to Harlem, especially since what you write about happens before Malcolm X really becomes a public figure?

KEVIN BAKER: He is a really classic American character, caught between race in a way that kind of defines the way that America deals with race. He was a black kid who ends up going to these white schools in Michigan. He was very smart, he was like third in his class, and was elected school president. At the same time, he goes to the school dance and is not allowed to dance with any of the girls there. Physically these white guys surround him and nonviolently but adamantly wall him off from the dance floor. His whole life is about being allowed a foot in the door but nothing more. His story really sums up the frustration of race in this country in that way.

Also, the Autobiography of Malcolm X this great, iconic American text, but there are obviously parts where Malcolm is doing things for a political purpose. It's a conversion story, and a story in which he's trying to claim leadership of the Civil Right Movement in the 1960s. So he exaggerates what a bad guy criminal he was, and various other things. Oddly, he also underplays how badly he had it at home as a child. The odd thing about Strivers Row in a way is that it is using fiction to get to the truth of Malcolm's nonfiction.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is it hard to write fiction about a historical figure when almost everyone has read his autobiography and seen that Denzel Washington movie about him?

KEVIN BAKER: Yeah, it is somewhat, and I have to admit I was picturing Denzel Washington at times, and I was picturing Delroy Lindo as West Indian Archie at times, too.

I've had major historical figures in these books before, but never in as central a role. Of course you feel more of an obligation to get stuff right. In Dreamland I was really terrified about getting the stuff about Freud wrong – of course, nobody seemed to really notice it afterwards.

I think, though a lot of people have seen the movie or read the book, there are a lot of Americans who really don't know a lot about Malcolm or the Nation of Islam. They think of Malcolm as this X hat or a poster with the finger jutting forward and the "By Any Means Necessary" caption. Our heroes and our iconic figures tend to get reduced to these clichés, and I think it is a good thing to try to bring out some more of where he came from to people. I hope I succeeded at this.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: What's next?

KEVIN BAKER: I have a contract right now to write a nonfiction book about New York City baseball.

But I also have other historical novel ideas about New York, and elsewhere, and a contemporary one or two. That's kind of frowned on in publishing; they've kind of declared fiction dead. But it's not. I'll be working in this field for a while now, I think.

Â

City Council Stated Meeting - April 5, 2006

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

QUOTES OF THE DAY:

"If you couldn't trust the Yankees for the last 83 years, what makes you think you can trust them now?" - Councilmember Charles Barron voting against a new Yankee Stadium.

"We will make sure they live up to their promises. And if they don't… the Yankees aren't the only ones who know how to swing a bat." – Councilmember Maria del Carmen Arroyo, voting in favor of a new Yankee Stadium.

MEETING SUMMARY:

YANKEE STADIUM

The New York City Council approved a plan to build a new Yankee Stadium in the Bronx by a vote of 45 to 2.

The council's action allows the Yankees to move ahead with a proposal to demolish the existing stadium, which was first built in 1923, and build a new 54,000-seat stadium next to it.

Much of the adjacent 22-acres Macomb's Dam and John Mullaly parks will bulldozed and replaced with a series of new parks. (For more on the parkland swap, read Gotham Gazette's article.)

Four new parking garages will also be built to accommodate about 3,000 cars.

Most council members supported the plan and argued that they successfully fought for concessions from the Yankee organization and the Bloomberg administration that will benefit the community, including:

- A commitment to build an additional 15 acres of parkland

- $8 million in funding to renovate another nearby park

- And 120 additional on street-parking spaces for area residents.

The day before the vote, Governor George Pataki and Mayor Michael Bloomberg said they would urge the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to build a new Metro-North Railroad station adjacent to the proposed stadium site, which will help reduce traffic congestion in the area on game days.

"This has been made a much better project, not just for the Yankees, but for the Bronx," said Speaker Christine Quinn.

In addition, the Yankees signed a "community benefits agreement" that promises that the organization will invest $700,000 a year into a trust fund that will be distributed to community organizations, pay $100,000 a year to help maintain parks, and give 15,000 free tickets a year to local community groups.

"Little kids will no longer have to play in parks that are dilapidated," said Councilmember Joel Rivera.

But critics of the plan like Helen Foster, whose district is near Yankee Stadium, said the plan was bad for the community.

The community board rejected the plan. No money has been committed to build a Metro-North Station. Some of the new athletic facilities will be built on top of parking garages. And while the Yankees will pay for the stadium, the city will pay approximately $130 million to redevelop the parks and build the parking garages.

"This looks like a win-win for the Yankees and leftovers for the community," said Foster.

Councilmember Charles Barron, who also voted "no," said that the Yankees have been bad neighbors for years and have done little to help one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city.

"If you couldn't trust the Yankees for the last 83 years, what makes you think you can trust them now?"

Councilmember Melissa Mark-Viverito questioned why the city is still building four parking garages when the Metro-North stop is meant to reduce automobile traffic; she voted against the parts of the plan related to the garages. The vote on the sections with parking garages passed by a vote of 44 to 3.

Two other council members - Rosie Mendez and Leticia James - abstained from the vote.

The meeting sparked spirited debate and advocates for both sides packed the council chambers. Neighborhood opponents passed out fake dollar bills with the face of Councilwoman Maria del Carmen Arroyo – who represents the district – on them, suggesting she had been bought by the Yankees. On the other side of the issue, Bronx Democratic boss Jose Rivera led a group of construction workers in a cheer of "Build It Now!"

The council's action related only to the land use aspect of the plan. The Yankees are also seeking $866 million in tax-exempt bonds to help finance the plan. The council has scheduled a hearing on the financing for the Yankee Stadium – and a new proposed Mets stadium – for April 10. The full council is expected to vote on the financing in three weeks.

Several council members said they would continue to monitor the Yankees to make sure they live up to their agreements.

"We will make sure they live up to their promises," said Councilmember Maria del Carmen Arroyo "And if they don't… the Yankees aren't the only ones who know how to swing a bat."

The Yankees plan to start construction on a new stadium this summer and finish by spring 2009.

BUDGET MODIFICATION

While the Yankee Stadium debate took up the majority of the meeting, the City Council also approved a modification to the existing 2006 budget.

It includes a $575 million allocation to help fund the Health and Hospitals Corporation, which has amassed a huge deficit.

The council also approved $1 billion toward a trust fund for retiree health benefits, a plan the mayor called for in his recent budget proposal.

The budget also includes an additional $16 million for the overhaul of the Administration for Children's services, which is hiring more caseworkers in the wake of the death of 7-year-old Nixzmary Brown, who was killed by her stepfather.

The budget modification passed by a vote of 46 to 3.

The three council members from Staten Island – Andrew Lanza, Michael McMahon, and James Oddo – voted "no" because none of the money for hospitals was allocated to facilities in Staten Island.

POLICE PAY

The council also voted on a bill (Intro 244) related to compensation for firefighters who have worked previously as police officers. The bill would not allow the firefighters to count the years they worked as police officers toward their seniority or pay.

The bill was introduced at the request of the mayor's office.

It passed by a vote of 39 to 10. Several council members said it was not fair to disregard the service of police officers. Charles Barron, Dennis Gallagher, Andrew Lanza, Mark Viverito, Rosie Mendez, Anabel Palma, Dominic Recchia, David Yassky, Vincent Gentile, and James Oddo all voted "no."

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for April 26, 2006.

Â

New City Council Bills

This week, we present a new feature - a selection from the many new bills introduced in the New York City Council that have not yet been passed. At the last meeting on March 22, 2006, the City Council introduced more than 50 bills, only a few of which will ever become law.

After being introduced, a new bill (called an "Intro") is sent to one of 27 committees. If the chair of the committee chooses, it can receive a public hearing and be considered. If a bill passes out of committee, it is sent to the full council. If passed by a majority (at least 26 of the 51 council members), the bill is sent to the mayor who has 30 days to sign or veto it. If the mayor vetoes the bill, the City Council can override it with a two-thirds majority. (Click here for a more detailed explanation of how a bill becomes a law).

Many of the bills that never became laws in the last session (only 137 of the 774 bills introduced in 2005 were passed) are now being re-introduced by council members who drafted them.

LOBBYING REFORM

Speaker Christine Quinn introduced three bills aimed at overhauling lobbying regulations in New York City. These bills are the first steps of an effort announced by Quinn and Mayor Michael Bloomberg earlier this year.

Intro 190 would require that the City Clerk educate lobbyists on existing regulations and undertake random audits to ensure that lobbyists who also raise money for candidates or serve as political consultants are reporting their activities properly.

Intro 191 would outlaw any gifts from lobbyists to elected officials. Currently, officials are allowed to receive gifts valued at up to $50. Violators would be subject to a fine of up to $30,000.

Intro 192 would change the city's campaign finance law so that contributions from lobbyists can no longer be matched with public funds. Currently, contributions are matched $4 to $1.

"We will ensure that the scandals of Washington and Albany do not happen here at City Hall," said Quinn.

The council will holds its first hearing on these bills on April 3.

FOILING TRAFFIC CAMERAS

Many New Yorkers first learn about the city's "red light cameras" after running a streetlight, thinking they got a way with it, and then a few weeks later getting a ticket in the mail. The city has about 150 cameras that take photos of a car's license plate after it goes through a red light.

But some have figure out how to foil the cameras, and the council is looking to stop them.

A bill, Intro 197, introduced by Councilmember Tony Avella, would ban the sale of chemicals that people can put on their license plates to prevent them from being photographed. The chemicals create a clear hi-gloss reflective finish over the license plate, which acts as a mirror to overexpose the photo, rendering it unreadable.

"There are companies that are selling chemicals just for the purpose of making license plates invisible to red light cameras," said Avella.

Under the legislation, businesses that sell the chemicals could be fined $250,000 or more.

TOY GUNS

Intro 240, introduced by Councilmember Al Vann, would increase fines for stores or companies that sell realistic-looking toy guns.

The council argues that toy guns are used to commit crimes, and that there have been tragic incidents involving young people carrying imitation guns who were wounded or killed by police officers who mistook toy weapons for real ones.

The legislation would raise the fines to between $1,000 and $5,000 for a first offense.

"We think that the sale of all toy guns should be prohibited in the City of New York," said Vann.

BULLET-PROOF VESTS

Intro 210, introduced by Councilmember Vincent Gentile, would replace the current bullet-proof vests used by police officers. In 2005, Officer Dillon Stewart was killed when a bullet went through a small gap in the left underarm of his protective vest.

"Recently there have been new technologies and new vests that would cover areas on the torso that were previously uncovered," said Gentile.

CITY CONTRACTS FOR THE "DISADVANTAGED"

The City Council is planning a series of hearings on a piece of legislation ( Intro 180-A) known as the "Disadvantaged Business Enterprise Bill," introduced by Councilmember Diana Reyna.

The purpose of the bill is to create more opportunities for specific companies to win government contracts. The legislation would add new categories to the existing Minority and Women Owned Business Enterprise Program.

In order to qualify a business owner must prove that they are either "socially disadvantaged," which the legislation describes as "experiencing social disadvantage in American society" or "economically disadvantaged," a person "whose ability to compete in the free enterprise system has been impaired due to diminished capital and credit opportunities."

Even those who helped draft the bill admit that the bill is still in its beginning stages. But the goal is to create a "race-neutral" category that would help business owners who might not qualify for other programs have a better shot at earning a government contract.

The council has scheduled a hearing on the bill for April 5.

Â

New York Nights

Twenty years ago, the city spent weeks dwelling on the story of Robert Chambers Jr., who killed Jennifer Levin in Central Park after the two teenagers left a bar on the Upper East Side named Dorrian’s Red Hand. Chambers was famously dubbed the “preppie killer", and the bar that served him and Levin became seen as his accomplice. On the day of Levin’s funeral, then-Mayor Ed Koch called for a citywide crackdown on bars that allow underage drinking.

Now, the killing and its aftermath are being mirrored by another high-profile crime: the rape and murder of Imette St. Guillen, a 24-year old graduate student last seen at a bar in SoHo named the Falls. Darryl Littlejohn, who was working illegally as the bouncer at the Falls, has been indicted for the crime, and the owner of the Falls, incidentally, is the son of the owners of Red Hand. Once again, officials are saying the city’s bars have something to answer for.

New York City’s nightlife has long been a crucial part of the city’s identity, and a major contributor to its economy. But bars and clubs also inspire suspicion and hostility, and are at the center of neighborhood conflicts over noise and development. As far back as the seventeenth century, the city's bar owners were losing their tavern licenses for serving “disorderly people", or being run out of town for selling liquor to Native Americans. [See Gotham Gazette’s related photo essay on nightlife]

Many residents of areas where nightlife is concentrated –- the East Village and Chelsea are particularly notorious –- feel powerless to control its spread, and unable to contain the hassles associated with their late night neighbors. Bar and club owners, meanwhile, complain about what they see as the automatic objections that many residents and public officials seem to have to places where New Yorkers go to have a good time.

The intensity of these conflicts generally rises in the spring, especially in the three years since the city imposed an indoor smoking ban. But this year, it seems, one issue has been moved to the top of the agenda: safety.

NEW YORK’S BAR SCENE

|

|

| Related Articles: - Williamsburg's Baby Bars - The Conflicted Past (and Present) of Christopher Street's Gay Bars - Photo Essay on New York City's Nightlife |

Drinking and dancing have never been far from the minds of New Yorkers. This is a city that once had a tavern with a door that connected directly to the municipal court. Later, it passed out tavern licenses to widows, seeing it as a cheap form of relief. City entrepreneurs actually invented the “night club" here in 1913 –- the original ones were members-only dancing venues created to avoid a new law forcing cabarets to close at 2 a.m.

Since then, New York's nightlife has helped nurture such staples of American culture as jazz and hip-hop. There’s also the warehouse-sized dance clubs that play electronic music for hundreds of drugged up dancers, and the faux dive bars that painstakingly re-create the grungy haunts of beaten-down drunks, but in a way that people willing to spend $6 for a pint of beer will feel comfortable. And the innovations continue: now that smoking is no longer allowed in bars, there are even bars where people are encouraged to bring babies.

Of course, most people go out at night looking for something distinctly less family-oriented. " Each of [the seven deadly] â€sins’ -- anger, lust, envy, sloth, greed, gluttony and pride -- plays an integral role in our local nightlife," writes Time Out New York in a recent article, “and there's no shortage of bars where a transgression can be observed or indulged in.???

Indeed, there are about 10,000 establishments in New York City licensed to serve liquor (the state makes no distinction between restaurants, bars, and nightclubs). Of these, about 1,175 are nightlife establishments, according to the New York Nightlife Association. There are 272 businesses with city-issued cabaret licenses that allow dancing, although they are not all necessarily dance clubs.

The city’s nightlife industry provides 95,500 jobs and pays $712 million in state and local taxes a year. In 2003, people paid 64.5 million visits to nightspots – more than three times the total attendance of all the city’s professional sports events and Broadway shows combined.

MAKING BARS SAFE

On February 24, Imette St. Guillen went to several bars, including the Falls, an upscale pub on Lafayette Street in Soho. The next day, her body was found wrapped in a quilt in a desolate corner of Brooklyn; she had been raped and strangled to death. Darryl Littlejohn, a bouncer at the Falls, was recently indicted for her murder.

It is clear that the owners of the Falls did something wrong, police say. In New York, bouncers must be licensed, yet Littlejohn, a seven-time convicted felon who would have been ineligible for such credentialing, was working without a license. Another illegal bouncer with a criminal past who was working at the Falls that night will likely be a key witness in Littlejohn’s trial. The bar’s manager also lied to police officers when questioned, first saying that St. Guillen left alone, but days later claiming that he asked Littlejohn to escort her out.

The State Liquor Authority could take away the Falls’ liquor license for hiring unlicensed security guards. But the case has also prompted a larger discussion about how best to keep nightlife safe.

Proposed Laws to Prevent Another Killing

Felix Ortiz, a state assemblyman from Brooklyn, has proposed two laws concerning safety at bars. The first one would toughen the requirements for those seeking licenses as bouncers at bars and clubs. The second, which he has named “Imette’s Law" would require bars to install security cameras. Had the Falls had a camera, said Ortiz, St. Guillen’s killing would probably have been solved by now – or not have happened in the first place. Civil liberties advocates oppose the measure saying it is invasive, as do nightlife industry groups, who believe it will cost them money without improving security.

Meanwhile, Peter Vallone, head of the City Council’s public safety committee, says he is involved in discussions about introducing a similar measure on the city level.

The council is also considering a bill introduced by Councilmember David Yassky that would allow the New York Police Department to arrange for off-duty officers to serve as security guards at clubs and bars – an arrangement already in place for other private businesses like owners of professional sports stadiums. The police department opposes the measure, saying it violates a state law that prohibits police officers from having an interest in a place that serves alcohol.

Better Enforcement

Others believe that the necessary laws are already in place, they just need to be enforced. Since the mid 1990s, bouncers at clubs and bars have been required to get credentials from the state. While many larger clubs have complied, it seems that smaller places are more likely to hire cheaper, unlicensed guards. They are rarely punished for doing this or, say critics, for health violations, noisy disturbances, drugs, or fights.

The State Liquor Authority has few inspectors working in the city, and has been notoriously lax in enforcement. But this year, Governor George Pataki has proposed doubling the number of inspectors statewide, and increasing the fines for violations.

The prospect of more inspectors is heartening to critics of the nightlife industry, but it is not seen as a panacea. Even when businesses are found breaking the law, they are not necessarily punished. Of the 788 Manhattan establishments charged with violations of their liquor licenses in 2003, only 10 had their licenses revoked, according to a Daily News investigation.

KEEPING THE NOISE DOWN

It happens once every two weeks once the weather gets nice, says Noah Hudon, a bartender at Blue and Gold on East Seventh Street: someone smoking in front of the bar gets too loud and “a tenant from the building next door – we have no idea who but someone with pinpoint accuracy – gets the culprit" with a bucket of water. He adds that they always deserve it.

Hudon believes that there is a state of “symbiosis" between the bar and its neighbors, where it helps make the neighborhood lively and nearby residents control its excesses. Others, however, do not necessarily see the relationship between loud bars and unhappy residents as a model of cooperation.

Tension over noise has only increased in the last three years, because the indoor smoking ban has pushed people outside late at night. This leads to more noise complaints from nearby residents, but bars insist that it is not their job to police the streets.

A New Noise Code

In December 2005, Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed into law the first major revision of the city’s noise code in 30 years. The code takes a wide look at the city’s noise, addressing the barking of dogs, the clatter of construction sites, and Mr. Softee’s jingle.

The code requires bars to keep quieter by lowering the actual decibel level that constitutes an offense. For the first time, it also regulates bass, a common subject of complaint for those living near nightspots. As a concession to business owners who say they are often cited unfairly, it now requires that police officers use a noise meter to determine whether a bar or club is actually in violation of the code, rather than relying on his or her own judgment.

But the noise code is not likely to end the disputes that the smoking ban has caused, though. While it tightens regulations on bars themselves, it does nothing to regulate people standing in front of them.

BARS AND THEIR NEIGHBORS

|

Some areas of the city slow down at night, while others, like Chelsea, the West Village, and Williamsburg, speed up.

The crowds begin descending on the Lower East Side on Thursday night and don’t let up until near dawn on Sunday, said Alexandra Militano of Community Board Three. With them comes noise, causing residents to constantly call the board and the local police precint. It also means an “exponential increase" in foot and car traffic, making it hard for buses and emergency vehicles to move up and down the area’s narrow streets and avenues.

The number of bars in the neighborhood has doubled in recent years, according to the Daily News, and Militano and others say it can’t take any more.

Enough Already!

Long time Ludlow Street resident Marcia Lemmon has been active in trying to stem the proliferation of bars in the area, and she also knows how nasty such fights can become. Several years ago, a local real estate agent was convicted of harassment after he admitted to making crank phone calls to her home late at night because she was trying to block his plans to build new bars in the area. (His punishment was community service at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum).

Lemmon thinks that it should be tougher to get a liquor license. The local community board, which advises the state on license applications, agrees. In recent years, community board three has named over a dozen “resolution areas", where it automatically recommends that the state reject the licenses. These areas include blocks on Ludlow and East 4th Streets, and all of Avenue B. The state has already rejected several applications upon the request of the community board.

“I don’t know that it’s anti-bar. It’s anti-being completely overrun by bars, which I think any neighborhood would be if they were in this situation," said David McWater, the community board’s chair, who owns several bars in the area himself. “So much of what’s happening makes people feel powerless and out of control."

Militano says that the reason for the resolution areas is to make business owners and the state liquor authority more responsive to the needs of a residential neighborhood neighborhood. Some business owners have decided not to pursue applications in these areas, she says, and more are coming to the board to discuss their plans for the area.

For her part, Lemmon says bars are only part of a larger problem. Rents are increasing as the neighborhood becomes more commercial, she says, “and the only people that can afford it, it seems, are the ones who hold liquor licenses."

Bars are People, Too

Robert Bookman bristles at the suggestion that residents are helpless against an invasion of bars on the Lower East Side. He believes that it is unreasonable for residents to demand “suburban quality of life at night" in areas that have always had nightlife.

“If you want to live in the center of Manhattan, there are disadvantages," he said. Bookman adds that the state shouldn’t give “unelected, appointed individuals [like community board three] the right to be local zoning boards without due process" by honoring their resolution areas.

It’s not always bars invading, argues Bookman. In parts of Williamsburg or the previously desolate portions of Manhattan’s far west side, residents are the newcomers, suddenly demanding peace and quiet in areas which have a lot of bars and clubs specifically because there used to be no neighbors nearby to wake up.

This is a problem for dance clubs in particular, because they are very restricted about where they can go. Because of the 1926 cabaret laws, establishments that allow dancing, no matter their size, are restricted to certain areas of town, and must have a special license.

Former mayor Rudolph Giuliani used these laws as a pretense for busting bars during his aggressive quality of life campaign, citing taverns for little more than allowing people to sway to jukeboxes. Mayor Michael Bloomberg had said he would like to change the regulations so they address noise, rather than dancing. The city’s one attempt to do so, however, was shot down several years ago. The laws remain in place.

Now a lawsuit calling for the city to abolish the cabaret laws outright is pending. Arguing that the laws violate their freedom of expression, a group of people who like to dance is suing the city. The cabaret laws have nothing to do with noise, traffic, or safety, said Paul Chevigny, a New York University law professor representing the plaintiffs; they were passed to control social behavior that made public officials uncomfortable.

“There was no sympathy for jazz and jazz dancing [when the laws were passed]; it was just seen as a scandal," he said. “I think there is still a puritanical streak that runs against social dancing, in the sense that it’s young people running wild, basically."

FRIDAY NIGHT FIGHTS

St. Patrick’s Day is perhaps the best holiday of the year for New York City bars. People begin stopping off for pints before the parade, and continue until late into the night. By 1:30 a.m. this year it looked as though things had started to die down on the intersection of 2nd Street and Avenue A.

But when a dozen police officers rushed into 2A, a bar on the corner, it was obvious that there were still plenty people out – it looked to have about twice as many people inside as allowed by the city’s fire code.

For the next forty-five minutes, bartenders tried to appease the police by thinning the crowd without chasing everyone away. Police officers shined flashlights into bottles of flavored vodka, looking for fruit flies, while patrons yielded their booths to health inspectors, who pushed aside empties to make room for their paperwork.

The lights eventually went back down and the music back up, but it was obvious the night was shot. Almost all of the revelers had drifted off, presumably to one of the dozens of other watering holes in the surrounding blocks, or to the pizza shops that seem busier than the bars at this time of night.

But the bartender still had a smile on his face, pointing out that, after all, "this doesn't happen every night."

There was no holiday to celebrate the next night. Even so, by 1 a.m so many people had packed inside that its windows were completely fogged up.

FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Neighbors and Nightclubs by Gotham Gazette

Nonsmoking New York? by Gotham Gazette

Williamsburg's Baby Bars by Gotham Gazette

The City New Noise Code by Gotham Gazette

Getting a Liquor License is Easy by Daily News

State Liquor Authority Rarely Revokes Liquor Licenses by Daily News

Too Many Bars by East-Village.com

New York Nightlife Association

Text of NY Cabaret Laws Â

City Council Stated Meeting - March 22, 2006

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

QUOTE OF THE DAY:

"The fact that it took my staff over 20 minute to print my remarks because the system kept freezing over is ample reason for the overhaul.” - Queens Councilmember David Weprin on the council's plan to spend nearly half a million dollars to upgrade its computer system.

MEETING SUMMARY:

Nearly two months after the City Council began its session and elected Christine Quinn as its new speaker, the legislative body's focus continues to be its own internal issues. This week, it proposed its own operating budget and remembered a former council member.

THE COUNCIL'S $50 MILLION BUDGET

The City Council proposed its own $50.7 million operating budget for the coming fiscal year. The budget covers salaries for council members, staff, office rent, and equipment. The council plans to increase spending by 2.5 percent - or a $1.2 million more than last year.

The number of staff employed by the council (278 people) will remain the same, and individual members will continue to make the same $90,500 base salary (although those who serve as committee chairs also get stipends ranging from $5,000 to $25,000).

Speaker Quinn said the additional money will be spent in three areas.

The council has allocated $303,000 for the creation of "Council Stat," a system for compiling constituent complaints from all 51 district offices. The database will be modeled after other initiatives like Comp Stat, the police department's system for monitoring crime. The goal is to track calls to individual members so that the council can better respond to community needs.

"We need to know what New Yorkers are calling us about so we can make sure we are doing the best job we can to solve their problems and also to see what the trends are citywide and boroughwide," said Quinn.

The council believes that its system will not replicate the 311 call line, arguing that people who call a council member are seeking help from a local government representative, not just a city agency. Speaker Quinn also noted that Mayor Michael Bloomberg does not share the data from 311, so it does not help the council in its role of serving constituents.

The council will spend $467,000 to upgrade its computer system, which members and staff complain is woefully out of date. The council staff currently uses three different e-mail systems and the Web site crashes on a regular basis.

"The fact that it took my staff over 20 minute to print my remarks because the system kept freezing over is ample reason for the overhaul," said Queens Councilmember David Weprin.

Finally, the council plans to spend a total of $281,000 more for rent for the main office at 250 Broadway and for individual members' district offices. Over the past two years, the cost of rent for district offices has increased by 14 percent.

In a break from the past, Speaker Quinn promised that she would not add more money to the council budget later in the year, as has often been the practice. Last year, after approving its budget in July, the council added an additional $2 million a few months later in November.

"We are committing to operating the council within that budget allocation and not to increase our spending mid-year," said Quinn.

RENT PROTECTION

The council passed only one new bill (Intro 118) which takes the first step in extending the current rent stabilization laws in New York City for another three years. The matter, however, is not fully within the council's control. The bill fulfills the city's responsibilty for continuing the regulations, but the State Legislature has ultimate authority on the matter.

So it also passed a resolution (Res 79) urging the State Legislature to repeal the Urstadt Law, which took control of rent regulation out of the hands of the city government and gave it to the state legislature in 1971.

"It is outrageous that we have to be subject to upstate laws that dictate the affordability of rent in the City of New York," said Manhattan Councilmember Miguel Martinez.

The measures passed by a vote of 48 to 2. Two Republicans - Andrew Lanza and Dennis Gallagher - voted "no;" the third Republican James Oddo was absent.

REMEMBERING ROBERT DRYFOOS

The majority of the meeting was dedicated to rememberances of former City Councilmember Robert Dryfoos, who died on March 2, 2006.

Dryfoos served in the council from 1980 to 1991, representing the Upper East Side. Members praised him for his efforts to save Radio City Music Hall from demolition, for developing educational TV programs such as "Live From Lincoln Center," and for his dedication to children's issues.

Dryfoos, however, was best known for a vote he cast in 1986, when he defied the Manhattan and Brooklyn Democratic political bosses to support Peter Vallone, as the first speaker of the council. Dryfoos had promised the leaders that he would support a Brooklyn representative, but at the last minute he gave his support to Vallone, handing him a victory by a vote of 18 to 17.

"It wasn't a vote for me," said the former Speaker Vallone, who made an appearance to honor his friend. "It was a vote for the independence of the council."

After leaving the council in 1991, Dryfoos founded a political lobbying firm called the Dryfoos Group, where he represented after-school programs, educational organizations, and the New York Junior Tennis League, which organizes tennis programs at schools across the city.

In recent years, Dryfoos was often at City Hall, and council members said that when it came to passing the budget there even was a list of programs that everyone referred to as "Dryfoos items."

"Soon we are going to be passing a bill that bans lobbyists from being on the floor of the council during a Stated Meeting," said Brooklyn Councilmember Lew Fidler. "But in spirit, Bob Dryfoos will always be on the floor of the council."

YANKEE STADIUM VOTE ON APRIL 5

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for April 5, 2006, when the council will vote on the proposal to build a new stadium for the New York Yankees in the Bronx.

For information on the issues surround the stadium, visit Gotham Gazette's Land Use Links in the News. To read about the parks involved in the stadium plan, see Yankee Stadium Parkland Swap.

Â

Stem Cell Research: Medical Miracle or Moral Morass?

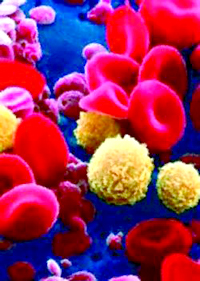

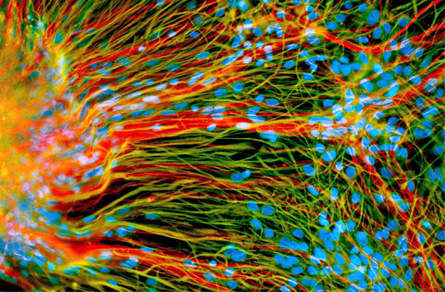

A microscopic look at a lab dish whose contents are derived from human embryonic stem cells

They have been likened to the dot at the top of an “i” and to tiny soccer balls. Some see them as the beginning of life, others as building blocks for medical miracles and still others as medical debris. And while most politicians would be hard pressed to define or spell blastocyst, these tiny bits of matter sit at the center of one of the most contentious policy disputes of our time – the fight over embryonic stem cell research.

Now the fight has come to New York. Ever since President George Bush banned most federal funding for most embryonic stem cell research in 2001, some states have sought to pick up the slack and so entice researchers and possible new industry. New York seems a likely location for this kind of research. Almost 55,000 people in the state work in the pharmaceutical and bio-tech industries, and the city is home to many top research institutions. With the construction of a new bio-tech center on the East Side, the Bloomberg administration hopes many private companies will bring their cutting-edge bio-tech businesses to New York.

To keep New York in the forefront of bio-technology, some members of the state legislature, including most prominently Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, hope to obtain state funding for embryonic stem cell research. On the other side, the Catholic church, which has spearheaded opposition to embryonic stem cell research here, argues that embryos used for stem cell research are a form of human life. The governor, meanwhile, remains somewhere in the middle – in favor of biotechnology in general but reluctant to support embryonic stem cell research explicitly.

As New York continues to mull the issue, some of its neighbors have moved ahead, threatening New York’s future as a center of bio-technology and, some say, delaying the day when sick people will get cures they desperately need.

WHAT IS STEM CELL RESEARCH

Although embryonic stem cells have not yet cured a single disease, it is hard to overstate the hopes that many experts have for them. Supporters of the research liken it to where antibiotics were 50 or 75 years ago. No one knows when, how, where – or even if – the major breakthroughs will come. But said Robin Elliott, the executive director of the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, who also serves as chairman of New Yorkers for the Advancement of Medical Research, “The same could be said of any frontier of medicine…This is an area of science that is potentially one of the most exciting in the history of medicine.”

|

|

The controversy over embryonic stem cell research involves balancing hopes for improving the lives of millions against fears of a Brave New World Society where human beings will be just another manufactured product.

Most embryonic stem cells used by scientists today are a byproduct of in vitro -- literally “in glass” -- fertilization, which has led to the births of hundreds of thousands of babies since 1978. The process involves surgically removing mature eggs from a woman – generally she takes drugs to enable several eggs to mature simultaneously – and joining the eggs with sperm in a laboratory rather than in the woman’s body. The fertilized egg is then implanted in a woman’s uterus where, if all goes well, it will develop into a healthy baby about nine months later.

Women trying to become pregnant through in vitro fertilization often have to undergo several implants before the procedure works. So most women store surplus fertilized eggs, and today thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of these small spherical blastocysts remain in clinics around the country.

For years, there was little use for most of the embryos, and ethicists debated what to do with them. Then in November 1998, James Thomson, a biologist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, reported that he had isolated human embryonic stem cells. These stem cells could renew themselves, by dividing again and again. With each division, scientists could create one differentiated cell – a blood cell, say, or a brain cell – and one stem cell, which could then be used to generate more cells. These related cells -– the offspring of the original cell -– constitute a group of cells, which scientists call a "line", that share the same DNA.

To create these lines, scientists have to separate the embryo into individual cells, thereby destroying it. They must then put the individual cell in a dish and provide it with nutrients and growth factors that will both encourage it to divide and create the differentiated cells. According to one count, there are about 240 human embryonic stem cell lines around the world.

Scientists hope the lines’ ability to create specific types of cells will enable researchers to understand a variety of diseases and eventually treat illnesses that entail lost or damaged cells, such as diabetes, some cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, and spinal cord injury.

For example, in people with Parkinson’s disease the cells of their brains cannot produce enough dopamine, which is essential to the functioning of the central nervous system. Brain cells created from embryonic stem cells could replace the deficient cells, enabling the patient’s brain to again produce dopamine and the nervous system to resume functioning normally.

This potential for possible cures has won embryonic stem cell research some prominent supporters, including Nancy Reagan, whose husband had Alzheimer’s disease; Michael J. Fox, who has Parkinson’s disease; and the late Christopher Reeve, who was paralyzed as the result of a spinal cord injury.

Since the 1970s, scientists have been studying adult stem cells, extracted from blood and bone marrow, as well as from organs taken from dead bodies. Working with such cells is not particularly controversial, and they are already used in areas such as bone marrow transplants and in treating eye injuries. But these older stem cells may be more set in their ways – scientists differ (in pdf format) over how versatile they might be -- and so unable to develop into some other types of cells. And the supply of these cells, particularly those from donated organs, is limited.

Because embryonic stem cells can keep dividing and renewing themselves for long periods of time, they could exist in greater supply. The problem, though, is where to get them in the first place. For now – and this is where in vitro fertilization enters the picture – most embryonic stem cells derive from blastocysts, several-day-old embryos that have not been implanted in a uterus. And these blastocysts come from in vitro fertilization clinics.

Scientists are trying to develop other methods to produce cells with the properties of embryonic stem cells. But for now, the cells come from embryos that are destroyed in the process.

THE ETHICAL ISSUES

This troubles many people, including leaders of the Catholic Church, members of the Christian right, and some, though certainly not all, anti-abortion advocates. They see the blastocyst as a human life and believe that destroying it – even to save someone from disease — is wrong. “We don’t think a human life should ever be a means to an end,” said Dennis Powst, director of communications for the New York State Catholic Conference. “It’s not an ethical way to go about curing disease.”

To underscore the link between the blastocysts and human life, President George W. Bush last year hailed the birth of 81 children from “adopted” embryos – dubbed “snowflake babies” -- and told a gathering of the families, “There is no such thing as a spare embryo. Every embryo is unique and genetically complete, like every other human being…. These lives are not raw material to be exploited, but gifts.”

The blastocyst legally belongs to the family that created it. A small number of these families turn their embryos over for adoption or for more medical research. But most of the embryos are now simply destroyed. Supporters of stem cell research argue that using the blastocysts to help find a cure for debilitating diseases would be far more ethical than just throwing them away.

Opponents of embryonic stem cell research also fear that the need for a steady stream of stem cells for research and treatment could lead scientists to try to create human embryos by cloning. “If cloning is not part and parcel of embryonic stem cell research,” said Powst, “we question why human cloning research is part of every bill” supporting embryonic stem cell research.

While most advocates of stem cell research say they oppose cloning for reproductive purposes they do support so-called “therapeutic cloning.” In this procedure, the nucleus of an adult cell is placed in an unfertilized human egg. Development would advance until the egg became a blastocyst but, advocates say, could go no further. There is, they stress, no way such an egg could ever become a human being.

THE POLICY HISTORY

In 2001, the Bush administration came down on the side of those opposing embryonic stem cell research. The federal National Institutes of Health said that it would only fund embryonic stem cell research using existing, self propagating lines of cells. But many of those lines turned out to be contaminated, leaving less than two dozen available for research. No federal money could go to create new lines.

In 2001, the Bush administration came down on the side of those opposing embryonic stem cell research. The federal National Institutes of Health said that it would only fund embryonic stem cell research using existing, self propagating lines of cells. But many of those lines turned out to be contaminated, leaving less than two dozen available for research. No federal money could go to create new lines.

The move did not ban embryonic stem cell research, but since the National Institutes funds most medical research in this country, particularly in areas where commercial applications remain years away, the action had quite an impact. “It’s mind boggling to researchers that the federal government has taken this action,“ said Maria Mitchell, president of AMDeC Foundation, a nonprofit consortium of New York medical schools and health care and research organizations.

The federal action discourages “an entire generation of young scientists from even going into the field,” said Susan Solomon of the New York Stem Cell Foundation. NIH bars research institutions from using any federally funded facilities for embryonic stem cell research. ”It’s a kind of McCarthyite environment,” Solomon said. “There’s a potential that since NIH is an executive branch creation that someone could come in and withdraw federal funding” from a lab doing work with embryonic stem cells.

Other countries, including England, South Korea and China, have continued to push ahead. And in the United States, individual states have begun to try to fill the void left by the national government. “Washington dropped the ball in our view. That’s the only reason this is coming up,” said Elliott.

In 2004, California passed a referendum, setting up its own agency that could provide $3 billion over the next 10 years for embryonic stem cell research. So far no money has been handed out because the measure is being challenged in court. Other states, including New Jersey and Connecticut, also have moved to provide money for stem cell research.

NEW YORK AND STEM CELL RESEARCH

A Hub for Research

In many respects, New York City seems a promising place for stem cell research. It is home to 49 teaching hospitals, eight major medical schools and eight medical institutions that are among the top 80 recipients of NIH research funds, according to a 2002 report by the Center for an Urban Future.

“New York is blessed with a real wealth of bio-medical research institutions and talent, “ said Ross Frommer, a spokesman for Columbia University Health Sciences. “Cutting edge research should be done at a place that’s good at doing cutting edge research.”

The Bio-Tech Business

Even though any commercial application of stem cell research is years, if not decades away, many leaders in medicine and research say the state cannot afford to be left behind. If New York does not fund stem cell research while its neighbors do, the state will lose the best scientists, research funds and, eventually, commercial opportunities. “In one word, it’s competition,” said Mitchell. “Not being involved in one of the most promising areas of research would put us at a huge disadvantage.”

If New York is seen as less than friendly to medical research, the state could lose out on more commercial aspects of bio-technology as well. Today biotech and pharmaceutical companies together employ almost 55,000 people in the state and pay $3.3 billion in wages, according to the New York Biotechnology Association. But New York State, and particularly the city, have lagged behind other areas in attracting commercial bio-tech jobs. In the past decade, says Maria Gotsch, of the Partnership for New York City, a business group, that situation began to change.

The City’s Effort