The Attorney General

One hundred and ninety years after Martin Van Buren used the position of attorney general to try to topple the governor, candidates Jeanine Pirro and Andrew Cuomo are trying to topple one another. Over and over again during their recent debate -- 16 times by one count -- Republican Pirro hammered her Democratic rival for a lack of experience, saying that as a junior prosecutor for only 14 months 21 years ago he did not understand the criminal justice system or know how to run a legal operation. And for good measure, she accused him of corruption.

For his part, Cuomo charged that Pirro is under investigation not only for seeking to wiretap her husband Albert, whom she suspected was having an affair, but also for failing to pursue corrupt officials in Westchester County. (Two days later, current Attorney General Eliot Spitzer said there is no such corruption probe.)

Such heated contests are nothing new for attorneys general.

The job was a source of friction between Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton. Burr defeated the Hamilton faction to win appointment as attorney general in 1789. The animosity between the two men continued for the next 15 years, until 1804, when Burr killed Hamilton in a duel.

Spitzer's predecessor, Republican Dennis Vacco, got the job after making it clear to any New Yorker who cared and many who did not that his opponent Karen Burstein was a lesbian, something she never sought to hide. Four years later, Vacco lost to Spitzer by a narrow margin but refused to concede until six weeks after Election Day, blaming his defeat on voter fraud.

All this conflict surrounds an office that in the past has been described "a bureaucratic and legal backwater," and "one of the state's least glamorous jobs."

FIGHTING FOR A 'BACKWATER'?

Even the two current candidates, who are spending millions this year to win the office, have not been very excited about the job, at least initially. Cuomo only sought the job after being forced to drop out of the race for governor in 2002. Pirro first tried to run for U.S. Senate this year, and in a taped conversation with Bernard Kerik said that being attorney general is a "been-there-done-that kind of thing."

|

The Other Statewide Offices Attorney general is one of four state offices whose occupants are elected by all New York State voters. All these posts are up for election this year: Governor: Twelve years ago Republican George Pataki scored an upset when he unseated incumbent Mario Cuomo to become the state's chief executive. With Pataki stepping down this year, the race to replace him has seemed a bit muted for a campaign for such a powerful post. Attorney General Eliot Spitzer easily defeated Democratic rival Tom Suozzi in the primary and now has a commanding lead in polls and in fundraising against former State Assemblymember John Faso. Lieutenant Governor: The state's number two office has little power. It is so obscure that only political junkies or the current occupant's friends or famiy can name her (Mary O'Donohue). The office got a little bit of buzz in Pataki's first term when then Lieutenant Governor Betsy McCaughey Ross raised eyebrows as she stood behind Pataki through 58 minutes of a speech he was making to the legislature. Pataki dumped Ross. In response she switched to the Democratic Party, announced she would run against Pataki and floundered badly. Just as the vice president runs with the president, lieutenant governor candidates run with governor. This year the Democrats have an unusually prominent candidate for the number two job: State Senate Minority Leader David Paterson of Harlem. Paterson is so prominent many wonder why he would want the job. If he wins, New York would "have affirmed an important principle: An African-American has the same right as anyone else to hold an inherently forgettable elective office," Clyde Haberman wrote in the Times. His Republican opponent is Rockland County executive Scott Vanderhoef. Comptroller: Former City Comptroller Alan Hevesi now holds the post of the state top fiscal officer. His re-election campaign garnered little notice until the Republican candidate, former Saratoga County Treasurer Chris Callaghan, found out that Hevesi had used a state employee to chauffeur his wife. Hevesi apologized and reimbursed the state almost$83,00, but the incident has prompted speculation about the integrity of someone entrusted with insuring the integrity of state finances. Despite that, Callaghan/s campaign continues to struggle, with little money or visibility. The Assembly speaker and the State Senate majority leader, though wielding enormous power throughout the state, are like other members of the legislature elected only by the residents of their districts. The members of the legislature then chose them for their leadership posts. |

But however some may disparage the job it certainly has a pedigree -- going back to the days of New Amsterdam when the schout fiscal was appointed by the West India Company to protect the company's interests in the colony and enforce laws and ordinances. And the job seems an essential part of government: Many nations and all 50 states have an attorney general.

Oliver Koppell, who held the office in New York State in 1994 and now serves on the New York City Council, likens talking about the office of attorney general to the old story about blind people describing an elephant. That, he says, is because "it has so many disparate functions that it can be described in so many ways."

Certainly, there are considerable administrative responsibilities. The office has over 500 attorneys and over 1,800 employees, including forensic accountants, legal assistants, scientists, investigators and support staff, and an annual budget of about $224,000,000.

In general, "the state attorney general is the chief litigator defending the state, the counselor rendering legal advice to state officials and the public advocate enforcing law designed to protect consumers, small businesses and the environment," Charles Burson, then attorney general of Tennessee and president of the National Association of Attorneys General once wrote.

The New York State constitution says little about the role of the attorney general beyond how the attorney general is selected (by election the same year the governor and comptroller are chosen) and that he or she heads the department of law. The duties of the state attorney general are set out in state law. These include, though are not limited to:

-- Criminal prosecution: The attorney general does not handle standard criminal cases but does bring cases against people who have misused state money. It can also investigate and prosecute cases of Medicaid fraud and corruption and works with local and federal officials on organized crime.

-- Protect the public interest: The Office of Public Advocacy can conduct investigations and file lawsuits, in areas such as antitrust, civil rights, consumer fraud, environmental protection, real estate and, most recently, internet transactions.

-- Collect revenue: As the state lawyer, the attorney general goes after people who owe New York money, including patients at state hospitals who didn't pay their bills and students at the state university who failed to pay tuition or repay their loans.

-- Defending the state: The attorney general is the legal counsel for the state and for state employees facing lawsuits related to their duties. These cases can range from sweeping suits, such as the Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit challenging the state's financing of New York City public schools, to malpractice cases brought against state hospitals.

This can be tricky when, as is now the case, the governor belongs to one party and the attorney general to another. In the school funding case, candidate Spitzer has said that, if elected, the city schools would get billions more, while Attorney General Spitzer has defended in court the governor's refusal to increase funding. "If you do anything less than that, you're not doing your duty," Spitzer press secretary Dennis Dopp has said.

But despite these various responsibilities, Koppell says, "the most frequent thing is to ascribe to [the office] functions that it does not have." For example, while many attorney general candidates over the years have sought to portray themselves as law and order candidates, the office has little responsibility for prosecuting standard crime; that task belong to local district attorneys.

A BROADER ROLE

But most recent attorney general have gone beyond the strict confines of the office, using their power to take up a variety of causes and filling gaps in the federal government's enforcement of the law. "The attorney general's office is capable of enormous elasticity," one former occupant, Robert Abrams has said. "The occupier of the office exercising leadership and his own degree of activism has the flexibility to move in certain direction."

In the 1920s, Attorney General Albert Ottinger, described as "a forebear to Spitzer in many ways," shut down the Consolidated Stock Exchange and said his legacy had been to "hammer, hammer, hammer at every manner and means of fraud and dishonesty."

Louis Lefkowitz, who served from 1958 to 1977, began taking on consumer protection. His successor, Robert Abrams, continued with that, cracking down on fraudulent and misleading phone and mail solicitations, enforcing the state's lemon law for cars, pursuing mail companies for fixing prices and suing businesses over confusing advertisements.

In doing this, Abrams was stepping into a void left by the federal government, which during the Reagan administration had little inclination to go after companies that hoodwinked or cheated consumers. "From a national perspective, we had a wasteland of consumer and environmental protection n the 1980s. It was critical that the states stepped in," Ed Mierzwinski, consumer program director for the U.S. Public Interest Research Group has said.

Similar, Koppell said that during his own year as attorney general he took up anti-trust actions, blocking a merger bid by Federated Department stores. Anti-trust also held little interest for the Reagan Justice Department.

But most agree that, for better or worse, Spitzer took things up a notch when he assumed office in 1999. "Eliot Spitzer has really pushed the envelope," Koppell said, particularly on issues involving Wall Street. He took advantage of a largely somnambulant state securities law called the Martin Act to go after Merrill Lynch for issuing false and misleading recommendations on stocks. As Abrams had done with his consumer work, Spitzer was filling a gap left by the federal government. "A feckless Securities and Exchange Commission has responded haphazardly to five years of scandal, leaving a vacuum for Spitzer to fill," wrote Daniel Gross in Slate.

He also pursued insurance companies and worked with city green grocers to agree to better working conditions for their largely immigrant workforce.

And, with the federal government under President George W. Bush reluctant to do much about pollution or global warming, Spitzer, along with seven other attorneys general and New York City officials in 2004 filed suit against five of the largest producers of the gases that cause global warming. In a kind of legal understatement, they used common law against creating a nuisance to support their claim. "Global warming threatens our health, our economy, our natural resources and our children's future," Spitzer said at the time. "Under accepted and unambiguous law, a court can order them to reduce their emissions."

Some critics think that during his eight years in office Spitzer has sometimes overstepped the bounds, partly to boost his own political future. "On the one hand, everybody respects that the attorney general filled a vacuum and cleaned up a series of abuses left over from the boom period of the late 1990s," Kathryn Wylde of the Partnership for New York City, a business group, told the Washington Post, "but there's an exhaustion factor that comes into play. . . . Every day it's a new issue."

"The problem with Eliot Spitzer and frankly a lot of the federal prosecutors is, in their zeal to appease public sentiment about various business practices, they've gone extreme," New York defense attorney Edward J.M. Little has said. "Almost any questionable business practice can be labeled a fraud."

WHAT WOULD PIRRO AND CUOMO DO?

The increased activism of attorneys general - in New York and elsewhere - may well continue after Spitzer moves on. "It is a position that is likely to grow in importance as the nation's Supreme Court, increasingly pro-state's rights, is expected to send a greater number of decisions back to the states for judgment," commented the public affairs television program NOW, which has covered state attorneys general extensively.

Certainly both major party candidates to become New York's 64 attorney general have set out ambitious, though widely different, goals.

Stressing her experience as Westchester district attorney, Pirro said one of her top priorities would be going after sexually violent predators. "My mission is to make sure we have civil confinement...to keep them away from our women and children" she said.

But, while expressing concern over sexual violence, Cuomo disputed Pirro's vision of the attorney general's job. "It's not a DA's office. We have 62; we don't need a 63rd," he said."

On the other hand, Cuomo wants to use the office to address political corruption and dysfunction in Albany. "The attorney general should be the chief public integrity officer," he said.

Some critics fault Spitzer for not having done more in this area. But Koppell thinks the attorney general cannot function as a crusader against corruption because it conflicts with one of the office's key roles. "How can the lawyer for state officials investigate wrongdoing by those officials?" he said.

Cuomo would continue Spitzer's policy of, as the candidate phrases it, "sticking up for the little guy" against big banks, corporations and the like. And Pirro and Cuomo agree both say they would use the office to go after Medicaid fraud

So does that make all the campaigning, the attacks, and the swirls of accusations worth it?

The attorney general position does have another thing going for it: Many occupants, including the current one, have tried to use it as a steeping stone. Lefkowitz lost a bid for New York City mayor to Robert Wagner and Abrams failed in his effort to be elected the U.S. Senate. Others such as Martin Van Buren and Jacob Javits, succeeded. Spitzer clearly hopes he follows in their footsteps.

But even if a term or two as attorney general does not lead to loftier public office, there is another reason to take the post Koppell says: "It's a wonderful job...You can make a difference in little ways and big ways."

Â

The Forgotten Attack On NYC

German spies attacked New York on July 30th, 1916. By blowing up a munitions depot on Black Tom Island in New York Harbor, Germany slowed the shipment of supplies to Britain and France from the ostensibly neutral United States. The explosion also caused enormous physical damage to the surrounding area, blowing out windows of buildings as far north as the public library on 42nd street.

German spies attacked New York on July 30th, 1916. By blowing up a munitions depot on Black Tom Island in New York Harbor, Germany slowed the shipment of supplies to Britain and France from the ostensibly neutral United States. The explosion also caused enormous physical damage to the surrounding area, blowing out windows of buildings as far north as the public library on 42nd street.

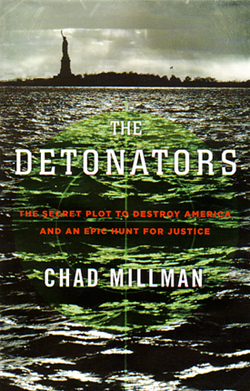

Despite being one of the largest attacks on New York in the city's history“ and a major terrorist attack on US soil planned and carried out by agents of a foreign government“ the event soon passed into obscurity. Chad Millman's book, The Detonators, tells the story of Black Tom Island. He recently joined Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club to discuss the attack on the city.

A FORGOTTEN CHAPTER OF HISTORY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Your book details a brazen terrorist attack carried out by a group of foreign nationals who are angry at American foreign policy. The details of the event bear a creepy resemblance to 9/11. Was it this resemblance, Mr. Millman, that inspired you to write the book?

CHAD MILLMAN: Absolutely, 100 percent. I've written some other books, but I'm a sports writer by trade. For my last book, I spent six months in Las Vegas tracking down people who bet on sports for a living, and I just didn't want to talk to anyone who was alive anymore. I wanted to deal with people who weren't around, and I could just dig into the research.

One of the things I've always liked to read is narrative non-fiction history. I was researching online on an "On This Day In History" web site. I started on January 1, 1900, and went through 1901, 1902, 1903, spending the better part of a day doing that until I got to July 30, 1916. There was a two-line description saying, "German terrorists blow up New York Harbor, much of downtown Manhattan destroyed." This was in March of 2002. I was living in Manhattan at the time, and I thought, "How have I not heard of this?"

I Googled and did some research, and there was nothing substantial written about it. I was stunned.

MARTHA SOFFER: Was this intentionally suppressed to save our macho American image that we've never been attacked?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, I don't think it was intentionally suppressed. At the time it was brushed aside. President Woodrow Wilson was campaigning on the banner that he had kept us out of war; he believed in peace morally and politically at all costs. There were several events leading up to this where there was a great amount of evidence that there were German spies operating in the United States, and that there were acts of sabotage in other munitions depots in the United States. Wilson's policy had been, "I don't want to know about this, I don't want to talk about this, I don't want this to be something we give credence to, because I don't want to go to Germany yet." Wilson's first response“ he was off the coast of Virginia on the Mayflower practicing his speech for the Democratic National Convention at the time“ was to say, "I'm not going to concern myself with the events at a private railroad." His Bureau of Investigation chief said in the New York Times that it was an accident. They clearly were trying to keep attention away from any act of espionage, because they wanted to keep the peace.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why do you think it's been completely forgotten about since then?

CHAD MILLMAN: I've been asked that question a lot, and I don't have a great answer. In terms of its place prior to World War I, it wasn't the thing that led us to war; that was the Zimmerman Telegram. If this is categorized as part of the World War I genre of history, then the final thing that catapulted us to war was that telegram, and this doesn't merit that level of attention. That's the only thing I can come up with; I haven't read anything better or heard of any better reasoning.

NEW YORK UNDER ATTACK

GOTHAM GAZETTE: In your research did you find out about any other attacks on New York City?

CHAD MILLMAN: There's always political anarchy, smaller attacks. Just a few years ago there was a bomb planted across from the post office on 50th street. In the early 1920s there was a lot of political anarchy and the Communist movement was underfoot.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: A book we talked about a few years ago described a plot by the confederacy to burn down several landmarks in New York City in the 1860s. But it was thwarted.

CHAD MILLMAN: It was such a battlefield back then. There was also that story about the German submarine off of Long Island in the 1940s, but nothing ever came of it.

It's awfully scary to think about all the things that has gone on and never happened. In the book I write about a group called the Black Hand in downtown Manhattan “basically Mafia“ they had been harassing and planting bombs in lower Manhattan. This led to an anarchist movement that was planting bombs. A lot of times they got caught because they blew themselves up. A lot of times you rely on the stupidity of criminals to uncover the deadliest plots.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Like when the Weathermen blew themselves up in the townhouse on East 11th Street.

WORLD WAR ONE IN NEW YORK CITY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How much of the economy of New York City was based on the war before the United States joined the fighting, and how did that change once the US did go to war?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, I don't know New York specifically. Throughout the country the exports to Britain and France increased hundreds of millions, billions, maybe. Phenomenally huge.

STEVE ARONSON: If the United States were neutral at the time [immediately before the Black Tom attack] what basis did we have to intern these German ships, and not allow them to leave?

CHAD MILLMAN: Our argument was that letting them leave was tantamount to supporting an act of war. If they came here, refueled, restocked, and strengthened themselves, then we were aiding Germany in the act of war.

STEVE ARONSON: What about the British ships?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, British ships, too. The thing was there was a British blockade in the Atlantic. It was the German ships, when they got caught on the wrong side of the blockade, who couldn't get back to Europe.

STEVE ARONSON: I would consider that an act of war.

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, Germany did. That's why they were so angry; they felt the American policies were hypocritical. There were all these interned German sailors in Baltimore and New York, and up the East Coast. With Black Tom, the largest munitions depot, in view of Manhattan, the Germans would see these ships loaded with munitions steaming off to war. They were angry, because American companies were selling munitions, and Wilson wasn't stopping them. The Germans couldn't buy these munitions, so their best bet was to blow them up.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: You write about the immediate physical damage in Jersey and Manhattan. Was there a larger economic impact?

CHAD MILLMAN: There was. It's funny, the mayor in 1914, when New York Harbor was becoming the busiest, wealthiest port in the country, said aloud "I fear for what would happen if someone tried to destroy this harbor." Immediately they declared you couldn't have munitions depots like this near large, populated areas. So yes, there was economic impact. I didn't see specific numbers; I just saw anecdotal evidence from people at the time saying how this was impacting the harbor. There were a lot of people looking for work at the time, so there were a lot of people out of work.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Did you find that there was anything similar to the feeling after 9/11 that people were worried that New York wouldn't seem safe anymore?

CHAD MILLMAN: No, I didn't get that at all. It was a different time. Before 9/11, it was such a placid, lush, flush environment in the US. It was so peaceful; there was no sense that this was coming. In 1916 there was a war going on in Europe, and there was a definite schism in the United States about whether we should go to war. This was after the Lusitania, and it was palpable that war could become inevitable. I don't think that people were as afraid as we are now.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Did you get the sense that the attack meant something different to people in New York than it did to people elsewhere?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, there wasn't this thing about rallying around New York as a victim like there was after 9/11. News traveled slower back then; there wasn't the instant reaction in places like Chicago and San Francisco that there was to 9/11.

GERMANS IN THE UNITED STATES AND NEW YORK

STEVE ARONSON: There must have been a group of people saying, "This was Germany." What impact did that have on American psyche at the time?

CHAD MILLMAN: Almost immediately there was a feeling that Germany had done this and that nothing would be done about it. There had been acts of sabotage leading up to Black Tom, and those had been written about in the papers often. It just became accepted that Germany was doing this, but that we weren't doing anything about it because we didn't want to go to war.

We also have to remember that while people died at Black Tom that wasn't the main goal of the saboteurs. They wanted to blow up the munitions depots so that the bullets didn't go to the front and kill Germans. They didn’t want to kill people like terrorists today. That's why there wasn't as palpable a fear.

MARTHA SOFFER: The German Americans were a very large, significant population.

CHAD MILLMAN: It was huge. Between 1880 and 1920 there was as many German Americans coming to the US as any other immigrant group. Before World War I, there was no immigrant group that was as admired or trusted as German Americans. There was a sociological study at the time that said that of all immigrant groups coming to the United States, it was German Americans who had the morals and principals that Americans most identified with.

Then World War I began, and all of a sudden there was this split. German Americans of first and second generation who had seemed so assimilated to the United States were suddenly staunchly in support of the motherland. And that's when a lot of the divisions happened. It became so bad that at one point they changed the name of sauerkraut to liberty cabbage. There were German communities all over the East Coast where the names of streets were changed. There was a street in Jersey City, Germania, whose name was changed to Liberty Avenue. They stopped teaching German at schools; German nurses weren't allowed to serve in the Red Cross because there was a fear they would grind up glass and put it into bandages. So there was a real fear of the German culture.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Just like French fries and freedom fries.

CHAD MILLMAN: There were so many times when my eyes would just bug out of my head, because I would be like "are you kidding me?" The similarities were stunning.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: New York City used to have an enormous German population and influence. Today this doesn't seem to be as significant as the Jewish, Italian, or Irish influences. Does that have something to do with the anti-German sentiment around this time?

CHAD MILLMAN: No, it didn't. The Germans settled here in two waves: the mid-1800s and the early 1900s. Unlike a lot of the Irish who were coming, the Germans came here with money. A lot of times they were leaving Germany for political reasons, and not because they were poor. So they came here with a lot of skills, built businesses, and by the early 1900s when the Irish and the Jews were immigrating here in larger numbers and settling on the Lower East Side and places like that, a lot of the Germans were moving to the Upper East Side, to Brooklyn, and to New Jersey“ to what was considered the suburbs.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Aside from the name changing and the things you mentioned, was there any actual persecution of German Americans living here at the time?

CHAD MILLMAN: There were stories of German priests being lynched when they were giving German last rites to people, and a lot of stories of violence against Germans when there were outward symbols of German heritage practiced by them.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Were there any government-sponsored actions that targeted German Americans?

CHAD MILLMAN: There weren't any outward acts of violence that the government was supporting. A lot of that was after the war. The American Civil Liberties Union started after the war to combat the persecution of people who were thought to be communists. That was a much more fearful time about the government curtailing civil rights than pre-World War I.

JERRY SILVER: When Pearl Harbor hit and a decision was made to intern the Japanese, was there some discussion at that time about doing anything to the Germans?

CHAD MILLMAN: You know it's funny, there wasn't. I've been asked that a lot. I didn't research this to any great extent, but there wasn't as great a fear of Germany because they hadn't attacked us. There was a fear of the Japanese because of Pearl Harbor, and there were other reports that there were Japanese submarines sending signals to citizens in California.

MARTHA SOFFER: The German population was so large, you couldn't intern them; the Japanese population was small. Plus the Germans could pass.

THE LESSONS FROM BLACK TOM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Directly after 9/11, the FBI began to examine the Black Tom bombings, to reopen its files and look at what it had. Did it find anything instructive or useful in that comparison?

CHAD MILLMAN: They just reacquainted themselves to the case. They didn't find anything that was so useful to find out why this happened on September 11, or when another one could happen.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Have you tried to come up with lessons learned from that event yourself?

CHAD MILLMAN: Well, the lessons learned were more applicable to World War II. The second half of the book is all about the investigation, and the efforts of three American lawyers to prove that Germany had done this. The lead lawyer was a man named John McCloy, who went on to have a distinguished career in politics. He was one of the architects of our Cold War strategy, and he was the first civilian high commissioner to Germany. His nickname was the chairman, because he was the chairman of the Chase Bank, and the Council on Foreign Relations, and the World Bank, and was an advisor to every president between FDR and Reagan.

McCloy became FDR's assistant secretary of war in the run up to World War II, mainly because of his work with Black Tom, and his work in investigating Germany. After Pearl Harbor, the discussion of the internment of the Japanese came up. FDR was well aware of the sabotage of Black Tom Island, and espionage, and enemies within the United States during World War I. They were both afraid of further attacks, and after they figured out a way where they could constitutionally do this, FDR was quoted as saying, "We don't want another Black Tom."

Municipal Television - A Clash Of Vision

On one channel, the titles of the shows have a tang – there is “Secrets of New York,” “Cool in Your Code,” “Globe Trekker,” even “Tommy Tang’s Modern Thai Cuisine.”

In the other channel, there are hours and hours of a show called: "The Council." (One recent highlight: “The NYC Council Subcommittee on Housing”)

The first is channel 25; the second is cable channel 74. They are both part of the NYC Media Group; they are both owned by City Hall. And they both are being criticized, for nearly opposite reasons.

Don’t misunderstand. Both are also praised.

The NYC Media Group, conceived by Mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2003 and consolidated into its present form in early 2005 and housed within the Department of Technology and Telecommunications, is comprised principally of flagship broadcast channel 25, and cable channels 71, 73, and 74.

Channel 74, which focuses on the doings of government -- hearings, press conferences -- now is also available online, certainly an innovation. (Channel 73 mostly offers programs in languages other than English geared for immigrants, and channel 71 is run by the New York off-track betting corporation.)

Channel 25 offers outstanding production values and broadcasts a schedule of cultural and entertainment programming with a New York slant that is so various and popular that, beginning in September 2006, some of the most popular night-time shows on 25 also began airing during the daytime hours on broadcast giant WNBC-TV. This was a first in city history.

But Gale Brewer, head of the New York City Council’s Committee on Technology in Government, argues that the government-oriented programming -- which is the reason behind municipal television in the first place, required by the City Charter (page 227) -- is often of poor quality and aired at inconvenient times.

From 1992 to 2003, the city’s first official municipal cable station, Crosswalks Television, exclusively aired government programming. NYC Media has departed considerably from this tradition, and this has led to clashing perspectives about the proper function of city television.

Brewer would like to see NYC Media devote some of the creativity that is evident on channel 25 to its government programming on channel 74. ( Despite popular opinion to the contrary, she does not believe that public affairs television must be stodgy and boring. Rather than a cooking show that is similar to those on the Food Network, for example, Brewer might broadcast a discussion with a member of the City Council about how the health department's proposed ban on trans-fats at restaurants would affect their district.

Brewer’s vision is directly at odds with that of Arick Wierson, the general manager of NYC Media Group. “We have to look like regular TV, TV that people are used to watching. So we made it hip, we made it flashy,” Wierson said following a recent council hearing to discuss the direction of NYC-TV. He noted that cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles and Houston are looking to New York for lessons about how to revitalize their municipal television productions.

Brewer suggests just the reverse, that New York can look to other municipalities for suggestions on how to enliven government programming. Among the innovations done elsewhere:

- Posting topics of City Council hearings on the Internet in advance of the hearings

- Running captions providing information about the topic of the hearing as they are broadcast (similar to C-Span)

- Providing interactive forums where city residents can speak directly to government officials.

Brewer also proposes other ideas that are not so common around the country:

- Developing “explanatory” programming that provides a broader context for the work of government officials and agencies

- Running snippets of a hearing, rather than gavel-to-gavel, then offering roundtable discussions of it and man-on-the-street interviews

- Partnering with film students to produce low-budget documentaries about how government works

- Broadcasting meetings that do not take place in City Hall, such as the gatherings of local community boards

Whatever changes occur on channel 74, Wierson plans to continue channel 25 as it is. As he succinctly stated at the recent hearing, "Television is meant to be watched". Â

New Bills -- Saving Middle-Income Housing and Improving Nightlife Safety

At each of the City Council's stated meetings, council members introduce bills, most of which will never become laws (for the process by which bills become laws, click here). As a regular feature, Gotham Gazette discusses some of the legislation proposed at each meeting.

At its most recent stated meeting on October 11, the City Council introduced several bills and proposed resolutions dealing with affordable housing, nightlife safety, civil service, and Con Edison.

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

With sales of large apartment complexes threatening to change the character of those developments, Councilmember Rosie Mendez introduced a bill that addresses the diminishing stock of low- and middle-income homes in the city. Intro 454 calls for a 120-day review period once a sale of any large-scale development is proposed. After conducting the review, the city’s housing preservation and development department would submit recommendations to the council and the mayor’s office on how to minimize the effects of any major sales, according to Mendez’s office.

The bill had been prompted by MetLifes decision to sell Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village on Manhattan’s East Side. But the announcement on October 17 that Tishman Speyer was buying the developments for $5.4 billion presumably limits any impact the measure could have on that. Mendez’s office said she is still moving forward with the bill in order to prevent future large-scale real estate deals from moving ahead without the city’s input.

NIGHTLIFE SAFETY

In its continuing focus on New York’s nightlife, the council got its first piece of public safety legislation coming out of the nightlife summit held last month by Speaker Christine Quinn. Intro 455, by Councilmember Peter Vallone, would require clubs to hire one bouncer per every 75 patrons. There currently is no law on the number of bouncers required. The legislation is one of several pieces already introduced regarding club security personnel, including the “Bouncer Control Act” that was passed in August.

RESIDENCY REQUIREMENTS

Many city employees who started working after September 1986 are required by city law to live in the five boroughs. At the request of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Councilmember Joseph Addabbo introduced legislation to alter this residency requirement and allow more public workers to live in counties surrounding the city. Intro 452 would allow certain unionized employees to live in Nassau, Westchester, Suffolk, Orange, Rockland or Putnam county. The move to relax residency requirements comes as many city employees find it increasingly difficult to find affordable homes within the five boroughs.

CON EDISON

Just one day before Con Edison released a report that deflected blame for the blackout in Queens in July, the council urged the federal government to investigate the utility. Vallone, who criticized the report, proposed Resolution 551, which calls for the federal government to look into Con Ed’s past and present failures, including its questionable response after nearly 100,000 residents lost power for almost two weeks. The resolution also calls for the possibility of a federally appointed monitor for the company.

Â

Stated Meeting -- Helping Low-Income Homeowners -- 10/11/2006

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting both to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Gotham Gazette covers these meetings.

The City Council took a small step to ease the cost of housing for low-income New Yorkers.

The council unanimously expanded an existing law that reduces property taxes exemption for low-income senior citizens and disabled New Yorkers who own their homes. Currently, seniors and disabled people must have incomes must have incomes of less that$32,400 to be exempt from paying part of their property tax. Council now has raised that limit to $34,400 for this year and will gradually increase that to $37,400 in 2009. To receive the maximum benefit, the homeowners have to have income of $24,000 or less now. That will go up to $29,000 in 2009.

The changes, said Councilmember Maria del Carmen Arroyo of the Bronx, chair of the committee would help people who may not be below the poverty level. (See related story on how that level is defined, The Poverty Commission: Measuring Up?) But she said, those who could benefit “still suffer day in and day out, making difficult decisions” on how to spend their limited incomes, sometimes having to choose between food and medicine.

Arroyo estimated that currently only about 40,000 of the possibly 60,000 New Yorkers eligible for the exemption apply for it. “We have to do a better job of informing seniors and disabled New Yorkers,” Council Speaker Christine Quinn said.

While praising the property tax exemption for low-income property Councilmember Gale Brewer urged her fellow members to try to provide some relief for elderly or disabled renters, who rent includes payments for their landlords’ property tax.

The council vote on the measures, Intro 445-A, was 47 to 0

AFFORDABLE HOUSING – FUURE MATTERS

There was also discussion of other, possibly more controversial, matters relating to affordable housing.

Saving Stuyvesant Town?

Councilmember Rosie Mendez introduced a bill, which if passed, would require that, when any large scale development is put up for auction, the city housing department conduct a study of what impact that sale would have on housing in the city. The measure is clearly aimed at the impending sale of Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, onetime middle-income housing developments on Manhattan’s West Side. “It is good public policy that would allow the city of New York to find out what is happening with our housing situation, “ Mendez said.

The possible loss of so many rent regulated apartments is “too important for the city to sit back and simply watch it happen,” Councilmember Daniel Garodnik, who lives in the development said,

But some question whether, even if is approved, any such law could take effect in time to affect that sale.

Tax Breaks for Developers?

Shortly before the meeting, the council received a report from the Bloomberg administration proposing changes in the 421-A program that gives a tax break to developers. Currently most builders who construct housing in the city get a tax break. But in a few sections of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they must build affordable housing, usually along with their other project, to earn their exemption from some tax increases. Now, the administration is recommending that those areas be expanded to include such desirable sections of the city as Lower Manhattan, parts of Harlem, Brooklyn Heights and other places on the Brooklyn and Queens waterfront. The administration would also set other new limits on the tax break.

Many of the proposed changes are aimed at encouraging developers to build more affordable housing. Some in the real estate industry have claimed such rules could hamper development in the city, while some housing advocates have criticized the administration for not going far enough.

The changes must be approved by the council.

At a press conference, Quinn did not take a position on the recommendations other than to say 421-A should be “as sharp and focused as possible.” She said council had just received the report on 421-A from the city and would be reviewing the recommendations. “Some changes are necessary, absolutely,” she said.

HUDSON YARDS

In other action, the council approved a package relating to the Hudson Yards project on Manhattan’s West Side. The measures extended the project’s boundary westward, and would allow the area – including the proposed site of the rejected Jets football stadium – to be part of the planning process. “This moves us ever closer to having the rail yards come before us in the land use process,” Quinn said. Council must approve land use changes and, during the fight over the stadium, Bloomberg had sought to keep the project out of the land use process.

The measure, resolution 547, which Quinn defined as consisting of “technical actions,” elicited little debate or controversy, indicating how things had changed since the furor over the stadium ended with its being rejected by a state panel. “What a difference 18 months makes,” said Councilmember David Weprin, chair of the Finance Committee.

The resolution passed by a vote of 43 to zero, with Councilmembers Charles Barron, Lew Fidler, Letitia James and Darlene Mealy, all of Brooklyn, abstaining. James, an outspoken opponent of the huge Atlantic Yards project in her district, said she was withholding her vote. Alluding to the fact that that basketball arena and housing development will not come before council, James said, “any yards in Manhattan and Brooklyn should be treated the same….In the borough of Brooklyn, we are treated differently.”

COMPOSTING

In a follow-up to its approval earlier this year of a solid waste plan for the city, the council approved a bill to encourage and improve composting of yard waste. Sanitation committee chair Michael McMahon of Staten Island said the new law will reduce the amount of garbage generated in the city and so reduce truck traffic. It requires that homeowners separate yard waste, putting it in garbage bins or paper bags, Currently many people use plastic bags for grass clippings and the like, requiring that the waste be removed from the bags before it can be used for compost. In addition, the clippings tend to become smelly when they are tied up in plastic. Under the new law, private landscaping companies will have to bring their waste to a composting site if possible.

The vote on Intro 431-A was 47 to 0.

“A green city is a clean city and when you combine a clean city with a safe city you have a happy city,” McMahon said.

Well maybe we need one more thing – a World Series championship. Many council members took advantage of the meeting just before the start of the League Championship Series to urge the Mets on to victory. Eventually even lifelong Yankees fan Councilmember Joel Rivera said, “Let’s go Mets.”

Â

The Poverty Commission: Measuring Up?

New York City officials have declared an ambitious campaign against poverty, but they must also put together a fuller picture of the effects of poverty in the city, according to Lawrence Aber, a member of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's Commission for Economic Opportunity, which last month released its report, Increasing Opportunity And Reducing Poverty In New York City. Aber, a professor of applied psychology at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Education, co-chaired the commission's “work group on data evaluation.” He chatted recently about the shortcomings in the current methods used to measure poverty, and about how to determine whether the city’s new anti-poverty efforts are succeeding:

THE SHAPE OF POVERTY IN NEW YORK CITY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: In its report, the Commission for Economic Opportunity says it wants to work towards developing a "more nuanced picture of poverty and well-being as experienced by New Yorkers." What don't the statistics we currently use tell us about poverty in New York City?

LAWRENCE ABER: The main statistic that the city and the nation use is the percentage of people in households with incomes below the federal poverty line, which is now $19,800 for a family of four. That official poverty measure has a lot of flaws. The main one is that it doesn't take into account differences in what it takes to live compared to what it took in the 1960s...

A second problem is that it doesn't account at all for regional differences in the cost of living. It's the same federal poverty line in Biloxi, Mississippi as it is in the Bronx. It doesn't stand to reason that a dollar goes as far in New York as it does in Biloxi.

The third big problem is that it is a measure purely of income poverty, and it doesn't include measures of families' wealth, assets, or debt. Imagine you're making $19,800 and you own your own house, car, and vegetable patch, and you don't have credit card bills. Then imagine you're making $19,800 and you don't own your own house, car or vegetable patch, and you've got extensive debt. The poverty line can't distinguish between those two families, and the second family is much more economically stressed than the first family.

The final problem is that [we] measure the percentage of people below a cutoff instead of some kind of continuous score. It doesn't stand to reason that someone who makes $10 above the cutoff is wealthier than a family that makes $10 below the cutoff.

1.5 Million Live In Poverty? Maybe Double That

GOTHAM GAZETTE: So do you think that the commonly cited figure that 1.5 million New Yorkers live in poverty is an understatement?

LAWRENCE ABER: Yes I do. That is technically the number of people who live in households with incomes below $19,800. Deputy Mayor Linda Gibbs disagrees with me somewhat, because she says that if you take into account the benefits that families get, then the number of people living in households with economic resources below that level is lower.

That's technically true.

But the official line would be much higher today if the original methodology [were reapplied]. That was based on studies that showed that it cost about a third of a low or moderate family's income to feed four people adequately back then. Now food costs less than 15 percent of a family's income. There are other expenses that are much, much higher: transportation costs for going to work, health care costs, childcare costs to be able to work. If you total up in price what on average it costs to provide minimally adequate food, shelter, clothing, basic expenses, for a family of three in New York City, Wider Opportunities for Women estimates that it costs over $40,000 to reach what it calls family economic self sufficiency.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: About how many New Yorkers would be below that line?

LAWRENCE ABER: I haven't run those numbers, but nationally it about doubles or triples the number of people who live in families that cannot meet their basic needs.

Economic Opportunity Index

GOTHAM GAZETTE: One of the recommendations in the commission's report to measure poverty more accurately is to create an Economic Opportunity Index. What is that?

LAWRENCE ABER: An Economic Opportunity Index wouldn't just measure poverty; it would measure a number of dimensions that might go into the economic security of New Yorkers. This would include the percentage of New Yorkers who are covered by health insurance, and the percentage of New Yorkers who are employed. The idea behind an economic opportunity index is to create something like the Dow Jones Industrial Average -- a composite score of many dimensions of the economic and social life of New Yorkers that represents their economic wellbeing.

A single score like that would have several advantages. First, if one dimension of economic wellbeing went up and another went down, you might say things got better or worse if you're only tracking one when, trading off, they stayed the same. A multi-factor system like that is going to create a more reliable gauge.

Second, it's an effective communications tool. One of the things the commission recommended is to demystify this process and help citizens of New York understand the economic health of their fellow citizens and the city as a whole. We think an economic opportunity index could be a big contribution both scientifically and from a communications standpoint.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is the city already collecting the data needed to do this?

LAWRENCE ABER: No. The city has a lot of the data, but a few things would have to be collected anew. Right now city data mostly comes from people who are seeking services. Well, if poor people aren't seeking services, they're not getting into the numbers. The only way you can get some of the numbers for the population of poor people as a whole is to survey them directly.

LOOKING FOR WHAT WORKS

GOTHAM GAZETTE: The report's recommended focus on the working poor, young adults, and children under five has been criticized as too narrow, but the overall report has also been described as too vague. What is your perspective on these critiques?

LAWRENCE ABER: First, on the issue of those three target groups: [the commission has] said very clearly that there is no intention to roll back any of the current investments in low-income families, the aged, welfare recipients, and a number of other subgroups of the poor for whom the city is already doing a fair amount.

The commission identified these three groups who, as the report said, we believe can benefit most directly, immediately, and dramatically from well-focused and coordinated interventions. I endorse that, and when you think of it, in a way they are groups that society as a whole invests the least in right now. Are these the only three subgroups to address? Absolutely not. Are they ones that represent over half the poor, and where we think we can identify strategies that could make a difference in the short-run and really significantly change things? Yes.

There will be a stage two of the initiative. If the city is successful in stage one, it should cast its eyes on the next challenge.

In terms of overly vague, there were 30 commissioners working on a five-month time line with a very active, ambitious, and savvy city administration. The main way we could reach consensus was to articulate recommendations at a general enough level to be of helpful guidance, but not to micromanage.

The people in the commission are not people in government, and they don't have all the technical resources necessary to turn general recommendations into a specific action plan. When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the initiative, he also charged Deputy Mayor Gibbs to come up with an action plan and implementation plan in 60 days.

The people in the commission are not people in government, and they don't have all the technical resources necessary to turn general recommendations into a specific action plan. When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the initiative, he also charged Deputy Mayor Gibbs to come up with an action plan and implementation plan in 60 days.

Things will get more concrete with the next phase of the action plan, and they'll get more concrete after that. It takes awhile for government to turn recommendations into specific actions.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Were you able to identify any specific programs or strategies for confronting poverty in New York City that you can definitely say, "this is something worth expanding", or, "this program is absolutely not working"?

LAWRENCE ABER: The city posed the challenge to itself that said, "How can we do this without more state and federal help"? I think that there was the perception that good quality childcare for our youngest kids both worked as a school-readiness strategy and worked as a work-support strategy. The childcare tax credit is an indication of the city taking responsibility to expand resources on a strategy that works.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Were there any strategies or specific programs that you didn't think were worth the investment?

LAWRENCE ABER: The commission did look at some strategies that did come under question, but I think there wasn't a lot of general conversation at the commission about things that weren't working. As a commissioner, I personally believe we should be ready to identify and eliminate expenditures that aren't having an impact on families' real economic security and investment, and then use that money to invest in more effective strategies.

We will undoubtedly find things where we want to shift the investment. That's hard to do in a commission where people pour their life's blood into different components of that. That job is going to end up falling on government. Personally, I think, appropriately so.

HOW WILL WE KNOW WE'RE WINNING?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: What tangible ways are there to measure the success of the city's effort?

LAWRENCE ABER: The first is that there are going to be action steps. In order to implement the childcare tax credit, for example, there are going to have to be several concrete steps taken. Some city and state legislative changes will have to be made, and a new governor will have to adopt these changes. Then the word has to get to families in ways that they actually take up the tax credits. Each of those steps is measurable; you can set up benchmarks.

The goal is to take each of the action items and create such measurable benchmarks, then track the city's progress against those benchmarks.

But even if city government does all of the things the problem can be getting worse if the nation goes into a profound recession. We would know that the problem is getting worse by having an alternative measure of poverty and an economic opportunity index; those would show a worsening economic condition for New York City residents caused by the national recession.

But these measures can't be used in a simple-minded way to say whether a city initiative is working, because other things affect the poverty status of New Yorkers.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How will city agencies be held accountable for their performances?

LAWRENCE ABER: The commission recommended that New York City continue to build on its beginning tradition of accountability in a couple of other areas in city life, [such as] crime control, and homelessness reduction. There, internal benchmarks are tracked, and commissioners are held accountable by the mayor, politically and directly.

We also encourage the city government to look at approaches in other places. The United Kingdom under Tony Blair developed a major anti-poverty initiative in the late 1990s. They have developed an approach where the budgets of national agencies are affected by whether they meet benchmarks or not. This is a process called joined-up government.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How long will it be before we can expect to see results?

LAWRENCE ABER: I think we can expect changes in government action in a year, changes in patterns of investment in two years, and changes in outcome in three years. That's enormously ambitious, but you see the logical sequence there.

One of the things that was emphasized to us a lot by Deputy Mayor Gibbs is how important the mayor felt it was to hold his administration accountable to measurable change. That's the kind of guy he is. I think he would fail by his own standards if there wasn't measurable change in three years. And I don't think he expects to fail.

Â

Independent Voters

There are 2.9 million New Yorkers registered as Democrats out of a total of 4.4 million registered voters, far more than any other party. But there are some 750,000 voters who are neither Democrats nor Republicans, and not members of any third parties either. They are independent voters, people who have registered to vote but have not affiliated with a political party. They make up the second-largest body of voters in the city. Indeed, there are more registered independent voters than members of the Republican, Conservative, Working Families and Independence parties combined.

There is not much concrete information on New York’s independent voters. Several pollsters report that registered independents are less likely to vote than registered members of a political party, but when they do, they tend to support Democratic and liberal candidates. According to pollster Mickey Blum, independent voters came out in substantial numbers for the 2005 election, and were more likely than registered Democrats (but less likely than registered Republicans) to support Michael Bloomberg for mayor.

Bloomberg's campaign strategist,Bill Cunningham, part of the Bloomberg 2005 team that created a $10 million database of voter profiles, says independent voters tend to be as concerned with ethics and governmental reform as with the usual voter staples of crime and health care. Cunningham says it is important to try to see which issues concern such a large number of voters: "If they took the time to register, they must want to vote. One just needs to speak to their concerns."

But candidates rarely do this, and Democratic strategist Hank Sheinkopf understands why. “There’s no reason to bother” reaching out to these voters, Sheinkopf says bluntly. They are not allowed to vote in the city’s primaries – and in New York City, the vast majority of elections are decided in the Democratic primary. And in those few instances where there is a competitive general election, "you don't want to wake up voters you can't control."

In other parts of the country, there have been several measures taken to try to bring independent voters into the process more equitably. These are open primaries and non-partisan elections. In New York City, the first exists in only a few cases, and efforts to implement the second have failed.

Open Primaries

Laws allowing independents to vote in a party's primary of their choice are plentiful nationwide. Almost half of the states even allow voters affiliated with one party some measure of opportunity to vote for a candidate from another party's primary.

In California, a voter initiative opened up their state's primary, and instituted a "blanket primary" system, where voters were allowed to pick and choose which party's primary to vote in for each individual race. But the US Supreme Court ruled(pdf format) the system unconstitutional, in a case brought by the Democratic Party, deciding that it infringed on the parties' rights. As a result, California now has a "modified-closed primary" which allows independents to vote for all races in one party's primary of their choice. Although the parties have the right to close their primary to outside voters, the major parties in California permit it.

Washington State used the blanket primary system for 70 years until it was ruled(pdf format) unconstitutional by a federal court in 2003. Voters then approved an initiative that created a "top-two" primary system, where voters could still pick and choose, as in the blanket system, but only the two candidates receiving the highest vote totals advanced to the general election.

Last month, a federal court struck down the system as unconstitutional. Washington is now using an open primary system modeled after Montana, where voters of any party affiliation can choose one party primary to vote in for all races, regardless of their affiliation. Under the new law in Washington, only major parties have a primary.

In New York, the Independence Party (not to be confused with independent voters) has reached out to unaffiliated voters, over the objection of the Board of Elections, which did not want the hassle and expense of accommodating them.

In 2003, the board appealed the Independence Party's decision to allow all voters to participate in their statewide primaries. In a scathing rebuke, the US District Judge hearing the case boiled down their argument to "we don't want to go to the trouble of ordering the adjustment of voting machines... to accommodate the Independence Party's constitutional rights. This would be 'machine politics' of an utterly new, and absurd, kind." The US Supreme Court has supported parties' rights to determine who can vote in their primary.

The following year, the Board of Elections at first refused to allow the Richmond County Independence Party to open up their primary in the 61st Assembly District to independent voters, but again the board was overruled by a federal court. The victory was, by most measures, a small one: Only 48 people total (whether independent voters or Independence Party voters) voted in that primary race.

What are the chances of the other political parties allowing independents to vote in their primaries? "If they want to vote in the Democratic Party, they can become a Democrat," said Herman "Denny" Farrell, chairman of the New York State Democratic Party.

Non-Partisan Elections

Three quarters of municipalities in the country now use some kind of nonpartisan election system according to Professor Doug Muzzio at Baruch’s School of Public Affairs.

In Mayor Michael Bloomberg's first term, he proposed a charter amendment to create a "nonpartisan election" system where the primary would be open to all voters and all candidates, regardless of party affiliation. Voters overwhelmingly defeated the proposal.

The cities whose primary system most resembles the 2003 proposal are Minneapolis, New Orleans, and Jacksonville.

What’s Good For Independents…

The arguments used for side-stepping the political parties go beyond an effort to include unaffiliated voters.

The Board of Elections, which manages and regulates the election process as it is laid out by law, is set up to be bi-partisan, rather than be independent. On the state level, it is made up of four commissioners, two from each major party, and two co-executive directors, one from each party, who are appointed by the commissioners themselves. In the city, a commission of ten appointees runs it, with one Democratic and one Republican commissioner from each borough, recommended by the county parties and then appointed by the city council.

This institutionalized partisanship has been blamed for much of the board's problems.

"To say you're going to get objectivity by insisting on partisanship, that's an absurdity," Governor Mario Cuomo told the Times in 1990.

A national telephone survey(pdf format), conducted in Feburuary 2006 by the, Caltech/MIT Voting Technology Project showed that an overwhelming majority of people - including registered Democrats and Republicans - prefer their elections to be run by a non-partisan elected board.

The partisanship goes even deeper than the commission. State law emphasizes party affiliation be considered in the county boards' staffing decisions by mandating that its staff consist of an equal representation of the two parties.

Bloomberg called that "a recipe for ineptitude."

"Party leaders dictate hiring decisions based on party connections - or family connections - not merit. This makes it very hard to fire incompetent workers, or to recruit qualified ones," he said. And he compared it to the judicial convention system, which was recently ruled unconstitutional, calling the two systems the "last bastions of political patronage."

Â

New York City Council Stated Meeting -- September 27, 2006

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Gotham Gazette covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

It would no longer be illegal to wash sidewalks with hoses or wash your clothing in the middle of the night under a new law passed by the City Council at its stated meeting on September 27, 2006. The law is intended to update the city's administrative code.

"What we have done in a fairly painstaking detail is go through the administrative code and find what is out-of-date," said Council Speaker Christine Quinn. She added that aside from being antiquated, some of the pieces of code being changed were "silly."

One can assume that Quinn's definition of silly includes subdivision (f) of section 20-268 of the administrative code, which says used clothing merchants cannot sell "any junk, old rope, old iron, brass, copper, tin, lead, rubber paper, rags, bagging, slush or empty bottles" -- or collect such items in a cart or a boat -- "unless he or she is also licensed as a junk dealer."

Subdivision (f) would be eliminated under the new law. In addition, tour guides would no longer be required to submit three letters of recommendation from New Yorkers to get licensed, 24-hour laundromats would no longer be illegal, and the special license for "the peddling of old clothes from house to house" would be eliminated.

While many of these regulations go unenforced, small businesses are often subjected to fines for inadvertently violating them, said Councilmember David Yassky, the bill's primary sponsor.

The council passed the bill (Intro 349-A) by a vote of 48 to 0.

The council also passed a resolution that would allow the city's Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications to solicit cable franchises interested in providing service to New York City. A similar resolution was in place until it expired in 2003.

Currently only two companies --- Time Warner and Cable Vision -- have contracts to provide bundled cable, telephone, and Internet services in the city. The resolution allows other companies to compete, which should result in lower prices and better service for consumers, according to Councilmember Melinda Katz, the measure's primary sponsor. The resolution was approved 48 to 0.

The Council also approved two mayoral appointments to the city's Board of Standards and Appeals, which hears cases from property owners seeking exemptions from the city's building code.

One of the appointees, Dara Ottley-Brown, was approved without incident. Several council members raised concerns about the other, Susan Hinkson, however. Councilmember Vincent Gentile criticized Hinkson, a Republican, of being overly partisan as the Brooklyn Borough Commissioner of the city's Department of Buildings, and Councilmember Lewis Fiddler said that she had not been forthcoming about an incident at a Kings Plaza in which several complaints were made that the public process was intentionally subverted to help a real estate developer.

The final vote on the appointment was 45 to 1, with two abstentions.

Fiddler voted against Hinkson's appointment; Gentile voted for it. Councilmember Bill De Blasio expressed concerns about Hinkson's relationships with developers and abstained. Councilmember Alan Gerson also abstained for what he described as unrelated "procedural reasons."

Â

Putting City Hall's Documents Online

How many public beaches are there in the city, and which of them are the dirtiest?

How much salary does Michael Bloomberg draw as mayor of New York City?

The answers to these questions are available online, thanks to Local Law 11, which since February 2003 has required all city agencies to post official documents online. The first law in the nation to do this, Local Law 11 was aiming to “improve the efficiency and accessibility of municipal government”

New Yorkers can now go to a government records page, where there are links to 15 general categories, from Business and Consumer to Transportation.

A little tooling-around in the Environment category yields the information (by linking to a report from August, 2004 called “Swimming in Trash? A Look into Cleanliness at NYC Beaches”) that there are seven public beaches in New York City, covering 14 miles of shoreline, and South Beach and Midland Beach, both in Staten Island, were found to be the dirtiest. The Labor Relations category ( section 1 in the civil list) offers up the information that a certain “MR Bloomberg” receives “$1.00” a year for “mayoralty.”

Unfortunately, it is not easy to find this information, or much anything else, without stumbling upon it. The implementation of the law has not lived up to expectations. Almost four years later, some city agencies have barely provided any of their documents at all.

Why City Agencies Are Not Following The Law

In Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy, the character Arthur Dent’s home is demolished because the notification from City Hall that they were going to bulldoze it "was on display in the bottom of a locked filing cabinet stuck in a disused lavatory with a sign on the door that said 'beware of the leopard.' "

New York City’s bureaucracy might not be quite as impenetrable. But many city agencies do not provide easy access to their official documents online; they are in effect breaking the law, local law 11. There are several reasons for their lack of compliance. For one, there is no enforcement mechanism; the law does not discuss penalties for agencies that do not comply. On a practical level, it is not possible for agencies to upload their documents directly to the online portal. Although this capability was envisioned from the beginning, as of this time all agencies must submit their documents to the City Hall Library, which does the posting. The most significant barrier to full compliance may be that the state’s Freedom of Information Law is structured around physical documents. To be fair, some provisions of the 1978 law -- which is the underpinning of open government in New York State -- did take account of society’s move into the computer age. But as of 2006, the law is still so oriented to responding to Freedom of Information Law requests for physical documents that it even specifies the maximum cost for photocopies that agencies can charge, while having little to say about electronic versions.

Some Agencies Better Than Others

A limitation of the online site run by the City Hall library is that documents are only arranged by category and not by agency as well. This makes it difficult to determine precisely the extent to which each city agency is complying with the law. Nevertheless, the categories are logical enough that it is possible to get a good sense of how various agencies have responded to Local Law 11.

Both the Office of the Comptroller and the City Planning Commission stand out in their compliance with the law. The Comptroller began posting documents online even before the law was passed, and keeps up to date within a month or so. More than 500 records from the comptroller’s office, mostly within the Finance and Budget category, are available online.

The bulk of the City Planning Commission’s documents are within the Housing and Buildings category. There are more than 750 documents in this section, most from City Planning. The earliest report from the City Planning Commission is from July 2003, not long after passage of Local Law 11. The latest was last month.

By contrast, the Recreations/Parks category has no reports at all. Although this appears to be an indictment of the Department of Parks and Recreation, a glance at the department’s attractive web site reveals that they do wish to communicate with City residents. Among other things the department’s own Web site provides are access to park maps, permit applications, and information for businesses. But compliance with Local Law 11 has not been a priority for the Parks Department. The Cultural/Entertainment category is almost as bad. There are only two documents here, both published in 2003.

How To Enter The Modern Age

The Department of Records estimates that the government records page receives as many as 3,000 unique visitors per week. There clearly is a constituency for this information. If City Hall sincerely desires that all official agency documents be available online in a centralized location—which, after all, is the point of Local Law 11—there are short-term and long-term ways to bring this about.

The short-term approach is to provide access to documents by agency as well as by category. This would not guarantee that agencies would submit documents, but at least it would be harder for them to avoid the spotlight if they did not.

Another useful enhancement to this page would be to set up a simple search function for the documents that works like Google. Right now you have to determine in advance which category a document is likely to fit within, and then scroll through pages of results.

The Freedom of Information Law needs an overhaul, so that the presumption underlying the law equates open government with free online access to government documents. Physical copies of documents should continue to exist, both for purposes of preservation and for the benefit of state residents without online access. With such a law in place, interested city residents could have the confidence to know that they can go online and find what they are looking for.

Â

New York City Council Stated Meeting -- September 13, 2006

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Gotham Gazette covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

Christine Quinn's City Council overrode its first mayoral veto on September 13, 2006, passing a bill designed to prevent price gouging at gas stations over Mayor Michael Bloomberg's objections. Speaker Quinn, whose term began in January, said that the Council and the mayor had "agreed to disagree."

After evidence of price gouging arose in the days after Hurricane Katrina, the council began working on a bill to prevent such behavior in the future. In July, it approved Intro 296, which says that gas stations must keep their prices the same for a 24-hour period before they can change them again. The Department of Consumer Affairs would enforce the regulation.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg vetoed the bill, saying that existing fraud protection laws were sufficient. "Telling a business how often it can change its prices is just not something that the City should do," said the mayor in his veto message. "It does not address the real issue, and unduly interferes with private enterprise."

The council overrode the veto by a vote of 43 to 6. Democratic council members Simcha Felder, Daniel Garodnick, and Helen Sears voted no, as did Republican council members Dennis Gallager, Andrew Lanza, and James Oddo.

Quinn downplayed the first legislative conflict in what to date has been a remarkably cordial relationship between herself and Mayor Bloomberg.

"A lot has been made of the fact that the mayor and I have a good working relationship, and we do, and we will continue to," she said. "But the mayor and I have both said repeatedly that having a good working relationship is not synonymous with always being in agreement."

Quinn declined to comment when asked whether she would be willing to take the mayor on in court over the matter – something that happened numerous times during Gifford Miller's time at the head of the council.

TRIBECA REZONING

The council also passed a measure to rezone a four-block area of Northern Tribeca currently zoned for manufacturing. Under the plan, the area would be opened for the development of apartment buildings and 180 spaces of parking in the area bordered by West, Watts, Washington, and Hubert Streets.

What was passed on September 13 was different than the plan first brought by Jack Parker Corporation, a real estate developer. The local community board, Councilmember Alan Gerson, and Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer all opposed the Parker Corporation's original proposal, saying the development would be too dense. An earlier council vote was delayed at the last minute when an agreement was not reached in time.

The maximum height of the buildings and the heights of the setbacks along Washington Street were reduced, and the developer agreed not to move big box stores into the spaces. Local critics dropped their opposition, and the plan passed the council unanimously.

ART COMMISSION

The council also voted on new appointments to various boards and commissions, a matter one council staffer described as a "housekeeping" matter before the meeting. But the appointments to the Art Commission -- the group that reviews decisions about public art and architecture on city property and serves as the caretaker of the city's public art collection -- provoked a strong response from many members of the members of the Black, Latino and Asian Caucus.