The following is an edited transcript of a meeting of the Gotham Gazette Book Club on March 29 with guest Kevin Baker, author of Strivers Row.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Kevin Baker is back for the third time to round off our discussion of his history of New York City by novel. We've discussed Paradise Alley, which takes place in the draft riots of the 1860s; Dreamland, which takes place during the large scale Jewish immigration during the early 1900s; and now Strivers Row, which takes place in Harlem during the second World War.

THE HISTORY OF HARLEM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How much of the Harlem that you write about is still left?

KEVIN BAKER: Thanks for having me. Not that much is actually left physically of that Harlem. The great dancehalls – the Savoy, the Cotton Club – are all gone. Small's Paradise, a great club where Malcolm X used to hang out as a young man that figures prominently in the book, that's now an I-Hop. A lot of those things have kind of vanished.

Strivers Row – the book's namesake – is still there. It's located on 38 and 139th streets – still two of the most beautiful streets in the city.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How much of the mood or spirit is left?

KEVIN BAKER: Some of it is still there. There's still a lot of vibrancy in the community, even if it's no longer a place that really thinks of itself as the cultural capital of Black America.

By the time I'm writing the book – 1943 – the Harlem Renaissance has already been crushed by the Depression. A lot of those earlier dreams – that the black community was going to come to equal terms with whites – had already been disillusioned. But it was still a place of incredible creativity. It was still a place with amazing music coming out.

One reason that it has changed so much is that Harlem was a ghetto. That's a term we use interchangeably with "slum", but there really is a difference. A ghetto is a place where all members of a certain religion or race are forced to live – whether they're Jewish or, in this case, black. That meant that everyone lived together. At Strivers Row you had not only doctors, lawyers, ministers, but also great musicians, composers – Hubie Blake lived there, WC Handy – prizefighters, all sorts of people. Anybody who made money in the community. That feeling is kind of gone now. There's less of a black elite there.

These are the ways that cities changed. It was a good thing that New York changed – people aren't kept in this ghetto anymore – but of course something is always lost when communities change.

Harlem is still changing and probably will change for good. What this will mean, I don't know. It will probably mean some good things – money coming in. It will probably also mean some people being forced out, which isn't so good.

It will probably be much less black than it has been.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: You wrote in an article in the New York Times that Harlem was a fluke. Can you explain what you meant by that?

KEVIN BAKER: Harlem was planned for this white elite – and that's the natural place for wealthy suburbs: on the periphery of the city.

It had been this sleepy Dutch and then Irish and other white ethnic village for years. Various parts were known as Goatville or Pigville, for the different animals that would run free in the streets. So it was made first into a snappier upper middle class white neighborhood, and was then being set up to be this blockbuster white elite neighborhood. But it was being developed too fast; people weren't moving up there that fast. Developers looked around and panicked.

At the same time, African Americans were coming all the way north. They had lived in a distinctive community since the Civil War Draft Riots, basically for their own protection as much as anything else.

Developers knew they could charge black people two or three times what they charge whites in the city, because the black people had very little choice about where to live. Between 1915 and the First World War Harlem was really established.

NYC: BATTLEGROUND FOR FREEDOM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Your trilogy discusses three distinct eras in New York City history. Why these three eras as a way to explore the city's history?

KEVIN BAKER: Manhattan particularly and New York in general has always been the most contested ground in America. From the slave rebellion of 1712, the supposed slave rebellion of 1741, the many riots of the 19th century, the draft riots, to the labor struggles, and movements for women's rights, civil rights, and gay rights, all these things were really fought out here as much as anywhere in the country.

The three eras I write about were crucial moments in New York City's – and therefore America's – history. Outsider groups forced their way into what was very white Anglo society that didn't really want them here except in a completely subservient position:

The Civil War was a crucible for Irish Americans who came here because of the potato famine, as I describe in Paradise Alley. They started this Draft Riot, opposing a draft into the Civil War. It was horrible; it featured many lynchings and horrible killings of black people in the streets of the city. But it was also put down in large part by Irish police and the military. This was their decision to be part of America – and being an American citizen might mean shooting your friends and neighbors in the street.

With Dreamland, it's the uprising of the 20,000 – the garment workers and the Jewish American experience. This to me was much more about calling America on its promises. The political machinery of the city had a certain democratic feature to it, but was run as this closed Irish clan – you could get everything as a favor but nothing as a right. And here were Jews very idealistically saying "No, this is what America promises and you have to deliver on this." This led to this huge garment strike and then, after that, the tragic events of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, which is the central event of Dreamland (and which we just passed the 95th anniversary of). This would change New York and America forever.

In Strivers Row you have African Americans, who aren't immigrants as we usually think of the term – they'd been here in New York as early as the Dutch. But they are far and away the most outsider group, and this is them forcing their way into the American democracy – whether other people liked it or not.

So it's these three groups and the three folkways they pursued towards getting equal rights. These are the great stories of our democracy. So much of our culture came from Jews, Blacks and the Irish. These are hard stories; they are more brutal stories than we are generally told. But they are great stories and I've tried to capture them.

WRITING HISTORICAL FICTION

BARBARA HIGGENBOTHAM: How you do your research?

BARBARA HIGGENBOTHAM: How you do your research?

KEVIN BAKER: I did most of the research for Strivers Row at the Schomburg Center, which is a fantastic, underused research center in Harlem. I went to many of the great black writers of the time. I also did a lot of reading of the Amsterdam News at the time, which was then as now the leading weekly in Harlem. Terrific paper then, and had some great stuff particularly from a guy named Dan Burley. He was covering everything – politics, entertainment, sports, and great little mood scenes in Harlem, jotting down every word he heard, all this great slang in Harlem in the early 1940s. You can't go wrong with these sources.

With Dreamland, a lot of the terrific Jewish writers of the age helped. Haunch, Paunch and Jowl; and Michael Gold's Jews Without Money. Leon Stein's the Triangle Fire. Triangle, by David Van Drehle, came out after I wrote the book. It's fantastic.

Mostly, I used secondary sources in the books. I'm not writing history here.

I know EL Doctorow likes to say, apparently, do as little research as you can get away with. Certainly Doctorow does this better than any of us, so there's that to be said too. I like to dig in as much research as I can find. It's the little things that tell you so much – the stuff you weren't expecting to find.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: It's great that you mention those books, some of which have been previous selections in this book club, and you can read the transcripts online.

Doctorow was also a guest here, actually. He said that "history written by historians is clearly insufficient", and that novelists also have an important part to play. " The important thing is that over the years there's a consensus about literature," he said. "Some of it makes it and most of it doesn't. The books that make it have, in some way, struck people as somehow true."

KEVIN BAKER: I think that's a very good point. Whether you're writing fiction or not, truth is what you're going for. Does this ring true? The novelist is interested in truth as much as the nonfiction writer. The novelist is looking for what is true in terms of how people act and how the world of human emotions works.

JAYNA GOODMAN: Don't you think that the history that you are going back and looking at can be made up to an extent? History oftentimes is written from oral history that has been passed from generation to generation. People naturally like to exaggerate in their storytelling, so history that wasn't necessarily documented at that very moment is already an extension of the truth.

KEVIN BAKER: One of the things that labeling it fiction enables you to do is speculate more – to kind of indulge.

RACE

GOTHAM GAZETTE: One of the differences between this novel and the others in the series is that while today there isn't that much of a controversy about Tammany politics or European immigration of past eras, racial issues are still a flashpoint. Did you approach this subject differently than the subject of your past books?

KEVIN BAKER: Obviously it's something you're aware of. Race has been this undercurrent of American life for 400 years. There's no getting around it. You'd be in denial to say you're not conscious of it. But I think it is something that does not get better by being left alone. I think it's only going to be through exploring it – through fiction, through nonfiction – that we attempt to make it better. And this is a very sympathetic portrayal of the Harlem community.

Maybe it's audacious to take on the topic, but all writing is an act of audacity. I think in some ways I'm as unqualified to write about Harlem as I was to write about Jewish immigrants and Irish immigrants. I was completely ignorant of all three.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: So it sounds like you don't think there's any sense of in-authenticity about a white author writing about the black experience.

KEVIN BAKER: No. It sounds clichéd to say it, but I think there is a basic humanity that connects us. In some ways, I think it's no more audacious than a male writer writing about a woman. All writing is this attempt to put yourself into different lives, different eras. If we don't attempt that, then writing will be this very shrunken, disfigured thing.

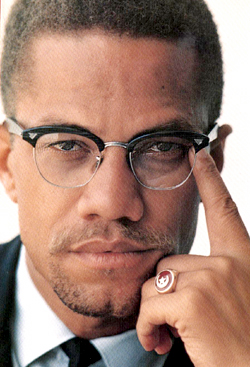

You draw upon things in your life. Malcolm X [one of the two main characters of Strivers Row] had this horrendous childhood, this very hard life. I can't say I know exactly what it's like to go through that in America. On the other hand, I was fairly poor growing up, we were off and on welfare, public assistance, and you get a little bit of a sense from that to know what it's like to be poor – to be an outsider. Again, not to the level that Malcolm experienced. But that is something you draw on.

MARTHA SOFFER: Did you get any negative feedback from the Afro-American community?

KEVIN BAKER: No, I haven't gotten any negative feedback. In fact, I have gotten more African American audience members than ever before – and glad for it. The emotion has been curiosity for the book. The worst response I got was from a white reviewer who thought I was unfair to the Irish. I'm mostly Irish myself. What can I say?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why did you decide to pick Malcolm X as the main character, someone who people know so much about, instead of picking a fictional young man who goes to Harlem, especially since what you write about happens before Malcolm X really becomes a public figure?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why did you decide to pick Malcolm X as the main character, someone who people know so much about, instead of picking a fictional young man who goes to Harlem, especially since what you write about happens before Malcolm X really becomes a public figure?

KEVIN BAKER: He is a really classic American character, caught between race in a way that kind of defines the way that America deals with race. He was a black kid who ends up going to these white schools in Michigan. He was very smart, he was like third in his class, and was elected school president. At the same time, he goes to the school dance and is not allowed to dance with any of the girls there. Physically these white guys surround him and nonviolently but adamantly wall him off from the dance floor. His whole life is about being allowed a foot in the door but nothing more. His story really sums up the frustration of race in this country in that way.

Also, the Autobiography of Malcolm X this great, iconic American text, but there are obviously parts where Malcolm is doing things for a political purpose. It's a conversion story, and a story in which he's trying to claim leadership of the Civil Right Movement in the 1960s. So he exaggerates what a bad guy criminal he was, and various other things. Oddly, he also underplays how badly he had it at home as a child. The odd thing about Strivers Row in a way is that it is using fiction to get to the truth of Malcolm's nonfiction.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is it hard to write fiction about a historical figure when almost everyone has read his autobiography and seen that Denzel Washington movie about him?

KEVIN BAKER: Yeah, it is somewhat, and I have to admit I was picturing Denzel Washington at times, and I was picturing Delroy Lindo as West Indian Archie at times, too.

I've had major historical figures in these books before, but never in as central a role. Of course you feel more of an obligation to get stuff right. In Dreamland I was really terrified about getting the stuff about Freud wrong – of course, nobody seemed to really notice it afterwards.

I think, though a lot of people have seen the movie or read the book, there are a lot of Americans who really don't know a lot about Malcolm or the Nation of Islam. They think of Malcolm as this X hat or a poster with the finger jutting forward and the "By Any Means Necessary" caption. Our heroes and our iconic figures tend to get reduced to these clichés, and I think it is a good thing to try to bring out some more of where he came from to people. I hope I succeeded at this.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: What's next?

KEVIN BAKER: I have a contract right now to write a nonfiction book about New York City baseball.

But I also have other historical novel ideas about New York, and elsewhere, and a contemporary one or two. That's kind of frowned on in publishing; they've kind of declared fiction dead. But it's not. I'll be working in this field for a while now, I think.

Â