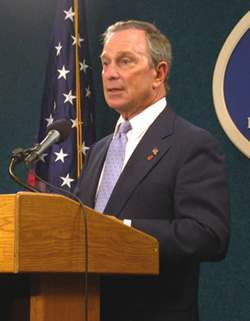

Mayor Bloomberg's 2006 Inaugural Address

“Happy New Year. Feliz nuevo.

“Governor Pataki, Mayors Koch, Dinkins and Giuliani, Comptroller Thompson, Public Advocate Gotbaum, thank you for being here.

“And thanks to all of New York’s distinguished public servants. Today I want to especially salute those who are leaving office: Borough President C. Virginia Fields, Council Speaker Gifford Miller, Councilwomen Tracy Boyland, Margarita Lopez, Eva Moskowitz, and Madeline Provenzano, and Councilmen Allan Jennings, Bill Perkins, and Philip Reed.

“And I want to say to the public servants taking their places how much I look forward to working with all of you.

“And, finally, I want to thank everyone here.

“Gracias a todos, from every borough and every community, for coming together on this wonderful day -- a day full of great promise for our great City.

“Over the past four years, I’ve met and talked with New Yorkers who practice every religion, speak every language, and come from everywhere on Earth. It’s been the experience of a lifetime, not only because of the generous warmth -- and advice -- you’ve given me, but also because you’ve shared with me your deepest hopes and dreams.

“It’s the enormous power of those dreams, over eight million of them, that gives our city its unique optimism, what one author described as: â€that sense -- so peculiar to New York -- that something extraordinary would happen any minute, any day, any month.’

“Possibility, Opportunity: This is the essence of New York. This is the air we breathe. This is the promise of tomorrow.

“But let us not forget, on Inauguration Day four years ago, that optimism seemed in jeopardy.

“The terrible devastation we had suffered only months before remained uppermost in our minds. From this very spot, we saw plumes of smoke still rising into the January chill from the World Trade Center site. We were a city in mourning, shaken and wounded.

“Accepting the enormous responsibility entrusted in me, I asked New Yorkers that day to keep faith in our common destiny, to think big, dream big, and prepare to build an even greater city.

“And because we did, today we are stronger than ever.

“True, the wounds we have suffered may never fully heal, but something else has endured. Something even more compelling; something even more powerful: our unity.

“On 9/11, New Yorkers came together. And since 9/11, we have stayed together.

“We’ve been united through blizzards and a blackout, and, most recently, we’ve overcome a transit strike that could well have shut down our city. We have accepted the risks and requirements of the post-9/11 world without abandoning our devotion to our liberties, our zest for life, or our feisty charm.

“United in the face of terrorism, New Yorkers have embraced the timeless wisdom that the secret of happiness is freedom, and the secret of freedom is courage.

“Over the past four years, we’ve learned -- or re-learned -- that in this, the most diverse of cities, we are one people, with one common destiny. That same spirit of unity must continue to guide us now.

“We have gone through the tough times, and come out stronger.

“Our population is at an all-time high. Crime is going down; student achievement is going up; jobs are being created; new homes and parks are strengthening and revitalizing our neighborhoods.

“We’ve come a long way, and now we have a choice to make.

“We could be content with what we have accomplished, and preserve our gains, or we can take our beloved city even further forward -- and make the promise of opportunity real for every person in every community.

“No one need ask which one we’ll choose.

“We are New Yorkers!

“We never stop reaching, striving, and working. We know there is more we can do, and more we must do. We know there can be no turning back. And there will be no holding back.

“United, we will take on new challenges -- with the passion and dedication that New York demands of us. United, we will succeed.

“Think about what we have accomplished in the last four years.

“Against all odds, we’ve made the safest big city in the nation even safer, for motorists and pedestrians on our streets, from fires in our homes -- at the tragic cost of six of our Bravests’ lives -- and dramatically safer from crime in each of our five boroughs.

“Now, staying united will make us even safer.

“Our most urgent challenge is ending the threat of guns and the violence they do. Twice in recent weeks, police officers have been struck down by gunfire on our streets. Twice the flags flying on this plaza have been lowered to half-staff, and the sound of pipes and drums has escorted brave and decent young men on their final journeys.

“Detectives Dillon Stewart and Daniel Enchautegui were among twelve of New York City’s Finest who gave their lives in the line of duty during the last four years.

“Now we have a duty as well, one that rises above all partisan politics, and one we will pursue relentlessly: And that is to rid our streets of guns, and punish all those who possess and traffic in these instruments of death.

“This is a national threat -- one that crosses city lines and state boundaries.

“To meet it, we must, and we will, make common cause with our fellow Americans.

“We will take our message to Albany, to Washington, and to every capital of every state that permits guns to flow freely across its borders.

“And to those who distort our laws to aid and abet hardened criminals, know this: We will not rest until we secure all of the tools we need to protect New Yorkers from the scourge of illegal guns.

“Public safety is the foundation of our city’s prosperity.

“Without it, our quality of life, our economy, our efforts to reform the schools would surely falter.

“Ensuring our safety has paved the way to taking on the other challenges we’ve faced.

“Working together, we’ve overcome the worst fiscal crisis in a generation. It threatened our quality of life and jeopardized our future. Courageously, together we made a fundamental choice to face up to the crisis, and master it -- and not postpone and evade, thereby repeating the mistakes of the 1970s.

“And because that was the right choice, we’ve done more with less, and today our quality of life is better and New Yorkers are living longer.

“Staying united, we will be fiscally responsible.

“This is not the time to relax our vigilance, or to make the wrong choice of shifting our financial burdens onto the shoulders of our children.

“City government can and must live within its means. And we will do so without abandoning the compassion that defines our city. We will care for the elderly, the homeless, and all those in need.

“City government must also be the catalyst of opportunity in all five boroughs.

“Private enterprise, not make-work public programs, always will account for New York's prosperity.

“The public sector’s role is to create the conditions that foster private investment. That is why, from West Harlem to Jamaica, and from Hunts Point to Coney Island, we are replacing long twilights of blight and abandonment with the bright dawn of new parks, new homes, and new hope.

“Staying united, we will transform the face of our city.

“We will protect and improve our open spaces. We’ll revitalize our incomparable waterfront. We’ll begin to turn what was once the world’s biggest landfill into the City’s largest new park in more than 100 years.

“We’ll pursue the most ambitious affordable housing initiative in New York’s history. We’ll encourage development where it’s needed, and curb it where it’s not.

“And we’ll quicken the pace of rebuilding here in Lower Manhattan, creating a sustainable residential and commercial community.

“By giving New York a genuine 21st century downtown, we’ll ensure that this -- our historic birthplace -- once again captures the imagination and admiration of people around the globe.

“Four years ago, our City was caught in a deep national recession, and our economy was hemorrhaging jobs. Because we’ve stimulated growth in all five boroughs, today, by contrast, our economy is once again moving forward.

“But for too many in our city, opportunity is still elusive.

“And so long as that is true, this will not be the New York that we want it to be.

“Staying united, we will create more jobs for all New Yorkers.

“Over the next four years, we will aggressively foster small business start-ups and expansion, and promote our growth industries -- from tourism, to the arts, to the life sciences.

“And because the best anti-poverty program ever devised is a job, we’ll also step up our efforts to move thousands more New Yorkers from the dependency of welfare to the dignity of work.

“Over the past four years, we’ve also started to fulfill our most important obligation: to our children.

“To give them the future they deserve, we’ve established accountability and set standards in our public schools.

“We’ve brought a sense of excitement and possibility to teachers, to parents, and to children. We’ve given the schools an arts curriculum that is worthy of the nation’s cultural capital. We’ve begun to ensure all our students the first-rate education that is their fundamental civil right.

“That is the hinge on which the future of our city will turn.

“Staying united -- for our children’s sake -- we can and we will lead our schools forward.

“We will lock in, and extend, all our hard-won reforms.

“We will not permit anyone to turn back the clock!

“Our mission over the next four years will be: To create -- from pre-school through high school -- a public education system second to none.

“We will strengthen the three pillars of our school reform: Leadership, Accountability, and Empowerment, putting resources and authority where they belong: in the schools of our city.

“And because the eyes of the nation are on our efforts, our successes hold the promise of hope for schools across the land.

“What a wonderful gift for New York to share with the rest of our country.

“We in this City can accomplish all these goals and more, but only if we continue to stay above narrow partisan politics.

“Over the past four years, New Yorkers have shown that we can solve any problem when we set our self-interest aside, and put our common interests first. Government must embody that spirit.

“We must make our political process more open and accountable, the operations of government agencies more transparent, and our methods of appointing and electing our judges above reproach.

“On Inauguration Day in 2002, I pledged to govern our city without partisanship or prejudice.

“I meant it then -- and I’m renewing that commitment today.

“The door to this great building will remain open to all New Yorkers, wherever they’re from, whatever they believe, whomever they love.

“Over the past four years, we’ve given New Yorkers a City government of independence and integrity.

“That will continue. We will not compromise our principles. We will not sidestep the hard choices. And we will always do what we believe is right for the people of New York.

“Forty years ago, New York -- as it’s done for countless others -- opened its arms and took me in.

“And during the past four years, I’ve had the chance to fall in love with this City all over again. I’ve learned even more what connects all of us to New York so deeply, what draws us here from every corner of the globe, and what keeps us here -- generation after generation.

“It’s possibility. It’s opportunity. It’s ambitions as bold as seeing your name in lights on Broadway, and as simple and universal as creating a good home and a better life for your children.

“That’s what New York City is all about.

“Our job, yours and mine, is to give every single New Yorker the chance to realize those ambitions and pursue those dreams.

“Four years ago, I spoke of building a better New York. And I can tell you exactly who is building it.

“It’s the couple who has just made the down payment on their first home in Cypress Hills. It’s the second-grader with a newfound love of reading, checking a book out of the Harlem Branch Library. It’s the returning veteran in Sunset Park who’s ready to exchange a helmet for a hard hat, and the shopkeepers on Fordham Road whose hard work and long hours are a labor of love for their families.

“You are the people who truly make this the place where â€something extraordinary happens, any minute, any day, any month.’

“You are making this a better City for all of us. You are the promise of New York, and we believe in your dreams.

“The challenges we confront are not easy, nor will they be the last ones New Yorkers ever face.

“After all, it was O. Henry who once wrote that, â€New York will be a great place -- if they ever finish it.’

“But over the next four years, we will neither turn back, nor hold back.

“Staying united, we will renew the promise of our city -- and commit ourselves to finishing our unfinished work, making Our City even greater and a true City of Opportunity for all of us here today, and for our children and our children’s children.

“Thank you, and may God bless New York City.”

Comptroller William Thompson Jr. 2006 Inaugural Address

Mayor Bloomberg, Public Advocate Gotbaum, Members of the City Council, colleagues in government, family, friends, and all New Yorkers, good afternoon.

It has been my great privilege to serve as New York City Comptroller for the past four years and I am deeply honored to serve a second term. And I would like to thank the people of New York City for this tremendous opportunity.

Four years ago, we gathered here under very different circumstances. Only a few months after the destruction of the World Trade Center , a deep uncertainty was heavy upon us -- our confidence shaken, our future in doubt.

Not only were we struggling to come to terms with the painful loss of family, friends and colleagues, we were confronting a bleak economic picture that threatened to take us back down the road of financial disaster we had traveled a generation before.

Remarkably, the leaders standing before you then, myself included, were new and untried in elective office. The eyes of the City -- indeed the eyes of the Nation and the World -- were upon us. But we did not shrink from the task. Staring into uncertainty can make some feeble: to New Yorkers, staring down uncertainty is what makes us strong.

This type of strength is what our City was founded upon. Long before Lady Liberty took up residence in our Harbor, New York City was a beacon to all people around the globe seeking to escape persecution and hardship. They showed the strength of their convictions and helped New York City become a symbol of freedom, a symbol of new beginnings, a symbol of rebirth.

The events of 9/11 tried to dim our beacon's light, but as it has so often in the past, our City showed its resilience and we emerged stronger and more secure. Today, our light burns brighter than ever.

I am proud to say that we faced the uncertainty and we prevailed. In fact, after a considerable period of economic decline, we have entered a period of fiscal stability and our economy has begun to rebound.

Yes, we are all proud that the City has bounced back more quickly than anyone anticipated, but in the wake of that recovery, there are still many New Yorkers who continue to struggle…who have not shared in this prosperity.

It is our responsibility as public officials to find ways to sow the seeds of opportunity, to foster hope for a better future for all New Yorkers. The challenges we face are enormous and it is not a time for partisanship. Collaboration was and still is the key ingredient for our future success.

I entered office determined to be an activist Comptroller, by aggressively using the powers of my office to find new, creative ways to save the taxpayers money and to put our resources to work for all New Yorkers.

With the unwavering focus of the dedicated staff of the Comptroller's office, we did this in a variety of ways. To name a few…We identified more than 170 million dollars in savings through our audits of city operations. We made innovative uses of technology, including an initiative to settle claims against the City electronically, and we found new ways to do business.

Taking advantage of New York's untapped fiscal strength, we collaborated with the Mayor, the New York City Finance Commissioner and the New York State Banking Commissioner to use over one hundred million dollars of City deposits as a capital base for expanding the Banking Development District program, spurring the creation of local bank branches in neighborhoods that have traditionally been excluded from access to capital.

Together with my committed colleagues on the New York City Pension Funds, we began to invest in real estate, specifically, New York City commercial real estate. Our pension funds now own part of several New York City landmark buildings. This investment is a true testament to our belief in the long term viability of this great City.

We have also invested our pension funds in the rehabilitation and creation of housing for our City's low-, moderate- and middle- income residents…nearly one billion dollars invested to spur economic growth and opportunity. And we developed innovative programs to include more women, African-American and Latino investment firms in the management of City pension dollars.

The list is expansive, and the focus clear…we have used our Office to help the beacon burn even brighter for all. Every New Yorker deserves their fair share of our economic recovery.

In the coming term, we will continue the work we have begun --- using City resources to benefit the people we serve: creating jobs, expanding access to capital, building affordable housing, and improving government.

We will ensure that the innovative Battery Park City Housing Trust Fund we established with Mayor Bloomberg and housing advocates honors the decades old commitment to create affordable housing units, helping thousands of hardworking New Yorkers and their families to live in our City without having to choose between paying rent or putting food on the table.

We will commit additional dollars to more bank branches in order to reach more neighborhoods. There is no better investment we can make than the investment we make in our communities.

We will continue to aggressively pursue contractors who exploit workers, many of whom are immigrants, insisting that the working men and women of our City are paid a fair day's wage for a day's work on any City public works project.

We will continue to lead the fight against companies that exploit children, discriminate against workers, do business in countries that support terrorism, and poison the environment, carrying on a long tradition of New York City Comptrollers who have helped us earn our reputation as the most aggressive pension funds in the nation.

I was born and raised in New York City . I have had the chance to get to know the many communities across the City in my career, and yet in the last four years, as I have met and worked with individuals and groups in every neighborhood, in every borough, I have seen a City stronger and more unified than ever before.

We are one City and we stand united no matter the challenge.

It is this commitment to each other that helps New York to continually reinvent itself and maintain its position as the greatest City in this Nation. Our City's legacy is and will remain one of opportunity, one of hope.

New Yorkers are survivors, yes—but we are more than that. Those who were born here, those who were raised here, those who come here from all over the world, are here, not just to succeed, but to excel.

There is a spirit in New York that is truly inspiring... a spirit that lifts its leaders to want more for the people they serve.

the years ahead, I will build on my achievements, deriving strength from this spirit. I will continue to fight for fairness and opportunity for all New Yorkers and to use the power of my office to keep our City strong.

Our city is, and must remain…a beacon for those who hope... a compassionate home for the vulnerable…and a place where every single New Yorker has the means to realize their dreams and aspirations.

Thank you.

Â

Three Days In December

What lasting mark will the three-day transit strike of 2005 leave on the city?

The 1980 transit strike, which lasted 11 days, gave New Yorkers at least three tangible things: dollar vans, women who carry their good shoes in their bag and walk to work in sneakers, and the term “gridlock,” coined by Sam Schwarz.

The 1966 strike, which began on the first day of John Lindsay’s administration and ended 12 days later, painted the mayor – either fairly or unfairly – as an unsuccessful leader and contributed to the notion of an “ungovernable” city that took decades to overcome.

Even a series of streetcar strikes in 1880s left a legacy of shorter workdays.

It is too early to tell what will come out of the transit strike of 2005. Some, for example, hope it will result in bicycling and even walking as the new norm for commuters, and in permanent restrictions on automobile traffic. But, for the moment, the walkout seems above all else to have brought to light a series of issues connected to public employment -- labor issues that go far beyond the beef between one union and its bosses.

PENSIONS

On the night of the union’s strike deadline, as midnight approached, it became clear that the conflict that was leading to the showdown came entirely down to pensions. In his last-minute offer, Metropolitan Transportation Authority Chair Peter Kalikow drew nearer to the union positions on many issues but demanded that all new transit workers pay six percent of their wages for pensions -– up from the current two percent. The union balked, with Toussaint saying the plan would, in effect, cut the wages of new workers by four percent and only save the MTA “a pittance.” And, indeed the New York Times calculated that, if approved, Kalikow’s proposal would have saved the MTA $20 million a year for the next three years – a tiny amount of the agency’s $9.3 billion budget for the next fiscal year.

But the significance of the move extends beyond dollars and cents. “This is not the end of it. This is just the beginning,” E.J. McMahon of the Manhattan Institute told the New York Sun. “What Toussaint has done is educate a whole new generation of New Yorkers as to how cushy pension deals are for workers by private sector standards.”

|

|

|

Transport Workers Union leader Roger Toussaint on his way to a press conference; Union supporters gathered on the Brooklyn Bridge

|

|

Fiscal watchdogs and some politicians have long sounded the alarm about what a post-strike editorial in the New York Times called "an issue of growing concern all across America." Even in the private sector, "pensions are increasingly at risk and increasingly self-funded," but public officials nationwide see the cost of pensions for public employees as a growing threat and the effort to scale them back a future source of friction. Mayor Michael Bloomberg has cited it as one of the "uncontrollable" expenses undermining New York City's financial future.

By one reckoning, the city's pension bill went from $3.37 billion last year to $4.74 billion this fiscal year. It could go to $5.08 billion for the next fiscal year, which begins in July, 2006. A recent analysis by the Public Policy Institute, a state-wide business-oriented group, found that people who had retired from state and local government jobs in New York collected an average of $22,676 in pension benefits in 2003, about 16 percent above the national average.

Under New York state law, governments cannot reduce pension benefits for employees. But they can impose new requirements for new employees, as Kalikow suggested. At the city level, divisions already exist. There are four pension "tiers" in New York, based upon the employee’s start date, and Bloomberg has said a fifth for those most recently hired might be useful.

Some fiscal watchdogs would go further and restructure the pension system. Today public employees are guaranteed a set benefit after they retire. In most private companies, though, employers and employees make a contribution to a retirement account. The amount the worker receives depends on how much money those investments are worth once the employees retires. The Citizens Budget Commission and the Manhattan Institute have urged that government switch over to this so-called "defined contribution plan." This would protect the government from the vagaries of the financial markets but leave the individual worker bearing that risk.

Some fiscal watchdogs would go further and restructure the pension system. Today public employees are guaranteed a set benefit after they retire. In most private companies, though, employers and employees make a contribution to a retirement account. The amount the worker receives depends on how much money those investments are worth once the employees retires. The Citizens Budget Commission and the Manhattan Institute have urged that government switch over to this so-called "defined contribution plan." This would protect the government from the vagaries of the financial markets but leave the individual worker bearing that risk.

Of course, the only reason public employees have such generous pensions is that politicians agreed to them in the first place. In 2000, for example, Governor George Pataki reduced to zero the amount that transit workers and other government employees with 10 years on the job had to contribute to their pensions. And Albany has given retired public employees cost-of-living increases in their city pensions, a measure that alone will cost the city $820 million a year by 2010, according to Doug Turetsky of the Independent Budget Office.

“Now, with a foot in New Hampshire on his way out the door, George Pataki has discovered that New York has a pension crisis and that 34,000 transit workers … should be enlisted to solve it,” Wayne Barrett wrote in Power Plays, a Village Voice blog, during the strike.

And while Bloomberg has spoken repeatedly of the need to reduce pension costs, “he certainly hasn't demanded it,” said Steven Malanga of the Manhattan Institute,” In fact, in his recent contract talk with the teachers union, Bloomberg agreed to establishing a labor/management committee that could consider way to cut the retirement age for teachers from 62 to 55.

HEALTH BENEFITS

Faced with rising health care costs, the MTA asked workers to begin contributing to their health care costs. Until now, transit workers have not had to pay anything for their health care coverage. The MTA asked that future workers contribute two percent of their salary toward their health care. The union said it would not agree to any deal that made workers contribute to health care costs.

Along with pensions, this quickly became one of the most contentious issues in negotiations – and one that city officials and fiscal and labor experts watched closely. While some critics of the union pointed out the relative generosity of the plan in comparison to private sector workers, others said cutting health benefits could set a bad precedent for organized labor. Days before the strike, Newsday columnist Ray Sanchez described the transit talks as a “historic fight against pension and health-care rollbacks for public sector employees.”

A normally empty afternoon PATH ride; people taking the LIRR from Brooklyn and Queens to Manhattan;

The line for the Brooklyn ferry

The city government’s health insurance costs are rising rapidly. In 2004 these costs totaled $2.4 billion; they are expected to total $3.9 billion by 2009.

Across the country, public and private employers are squeezed by health insurance costs. Some private employers no longer provide health insurance to workers, and most of those that do require that workers pay an increasing share of the costs.

Public employees, on the other hand, have not seen this erosion in benefits and now receive much better health plans than workers in the private sector. According to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, local and state governments pay well over twice the rates that private employers do to insure workers (in pdf format).

But while Mayor Michael Bloomberg has frequently cited health care costs as contributing to future city budget deficits, critics say he has done little to address rising health care expenses and that, in the latest round of contract negotiations, did not gain any concessions from unions on such costs.

Malanga says the city should either reduce the amount that it pays for health benefits or find ways to offset the expenses.

A TOUGHER DEAL FOR FUTURE WORKERS

When transit talks reached an impasse, the issue was not about benefits or wages for union members -– it was about the benefits that future transit workers would receive.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority wanted to give future workers less generous pension and health care packages but, as Peter Kalikow, the authority's chair, repeatedly pointed out, the plans of current workers would not be affected.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority wanted to give future workers less generous pension and health care packages but, as Peter Kalikow, the authority's chair, repeatedly pointed out, the plans of current workers would not be affected.

Still, union chief Roger Toussaint emphatically rejected the idea. "We will not sell out the unborn," he said, using a phrase he invoked repeatedly throughout the negotiations.

Historically, however, compromising with the benefits of future union members has been the easiest way for unions to respond to employer demands for cuts in expensive benefits.

"It's a common experience, and it's a way for a labor leader to make an unpopular decision in a way that his members -- the members who elect him or her -- don't have to pay for," said CUNY professor John Mollenkopf.

Unlike Toussaint, not all municipal union leaders have stood in solidarity with their future brethren. District Council 37, New York's largest public employee union, agreed earlier this year to give future workers fewer vacation days. And when given the choice this June, the Patrolmen's Benevolent Association decided to drastically cut the salaries of future officers and police cadets to pay for today's raises, instead of agreeing to other cost-saving measures.

Such action could lead to intra-union tension, as new workers enter the union with less favorable contracts and grudges toward the old guard leadership. In the case of the police officers, some also cited a fear that it could reduce the effectiveness of the police department.

"Setting a cadet's salary at $25,100 is no way to recruit the Finest," wrote the Daily News in an editorial in June, "and it illustrates how mulish the PBA and President Pat Lynch can be in refusing to accept productivity improvements.”

WORK RULES AND PRODUCTIVITY

Since becoming mayor, Bloomberg has invoked a kind of mantra in dealing with unions: Any salary increases will be at least partly paid for by increases in worker productivity. “From his statistic-packed management reports, to the bullpen cubicles he's made city administrators sit in, the CEO-turned-mayor is always looking for ways to improve output,” according to WNYC’s Dan Blumberg.

This issue arose early in the transit talks when the MTA sought to change rules for transit workers’ broadening job responsibilities. For example, the authority wanted conductors to become customer service agents who would roam the train, rather than stay in the conductor’s booth. Similarly, the MTA wants the former token clerks to move around subway stations and help riders. The union has expressed reservations about employees’ safety in stations, and passenger safety if conductors’ duties are changed. As negotiation went on, this issue seemed to fade although it could still emerge in a final settlement.

While Bloomberg has certainly sought productivity gains, it remains unclear how much he has actually accomplished in this area. While he has not gotten everything he has wanted, “labor experts say, he has wrung more productivity increases and other concessions out of the unions than previous mayors have,” Steven Greenhouse wrote in the New York Times.

Perhaps most significantly, this fall, the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Union received a 17 percent pay hike over 51 months after they agreed to longer trash collection routes and to allow one person, instead of two, on trucks that pick up large roll-on bins.

The city also got some productivity gains and changes in work rule from the United Federation of teachers in their new contract. The teachers agreed to three additional professional development days – work days for them but not for students – in the school year and 50 minutes more a week, limited some seniority rights and gave administrators more flexibility in assigning teachers to such non-instructional tasks such as patrolling lunchrooms and playgrounds. Noting that the contract continues the practice of swamping “time for money,” the Citizens Budget Commission commented, “This policy is very expensive. The added time bought in this contract has an extra annual cost of about $230 million.”

And the Manhattan’s Institute’s Sol Stern said the contract was a far cry from the changes originally sought by Schools Chancellor Joel Klein who had wanted to scrap a whole array of contract provisions and replace the 200-page contract with a streamlined eight-page document. But in the end, Stern wrote, “Mr. Klein bit his lip and affixed his signature to yet another 200-page teachers contract — one containing the same lock-step pay schedule, based on seniority and useless education credits, he earlier promised to end.”

The gains in productivity and work rules have also had a price beyond dollar and cents, according to some observers. "In a kind of nonbelligerent way, [Bloomberg] has taken a very hard line, and his insistence on productivity givebacks has made labor relations very, very difficult," said Joshua B. Freeman, a labor historian at the City University Graduate Center.

RESPECT

If Freeman is correct, the animosity may arise from the fact that work rules – how employees are treated on the job – go very much to workers’ feeling about whether their bosses respect them. Time and again, union leaders have said the city was not giving them the credit and respect that they deserve.

If Freeman is correct, the animosity may arise from the fact that work rules – how employees are treated on the job – go very much to workers’ feeling about whether their bosses respect them. Time and again, union leaders have said the city was not giving them the credit and respect that they deserve.

When the city suggested the Uniformed Firefighters Association, which is still without a contract, consider DC 37’s agreement as a model, firefighters president Steven Cassidy reacted scornfully. “Mayor Bloomberg says we're no different than people who just push paper,” he told WNYC. “That's a joke. It's an insult to police officers and firefighters who risk their lives everyday.”

Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association President Patrick Lynch has expressed similar sentiments. "We put on a shield on our chest, a gun on our hip and we go out and we go where no one else goes," he said. "And you're not going to respect us?"

After eight years of attacks from former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani followed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s takeover of the school system, teachers have felt insulted as well. "It's time to invest in the new three R's," UFT President Randi Weingarten told a “Respect for Teachers” rally in 2003. "Respect for teachers. Retention of qualified staff. And resources for schools." Teaches felt so slighted by what they considered micromanaging of classrooms by Chancellor Klein – a man with virtually no education experience before he began running the nation’s largest public school system – that the new contract specifically bars disciplining teachers for violating some of Klein’s rules about lesson time and bulletin boards.

Amid all the dollars and cents issues in the transit talks, “respect seemed to be the driving motivating factor,” Bruce Schaller wrote in Gotham Gazette. Workers have cited what they see as petty and punitive rules and arbitrary disciplinary actions against them. Workers are “punished and harassed daily by management,” Juan Gonzalez wrote in the Daily News. One worker told him, "We've been fed up with the MTA and wanted a strike for years."

And so, they got one. But it is not clear whether any strike could give the transit workers more respect or really resolve the many thorny issues facing New York’s government agencies and their workers in the months and years ahead.

All Images from Flickr

Â

City Council Stated Meeting - December 21, 2005

MEETING SUMMARY:

The New York City Council met for its final session of the year and passed more than a dozen new bills.

NOSTALGIC FAREWELLS

It was the last meeting under Speaker Gifford Miller, who is term- limited out of office. In addition, seven other veteran council members - Margarita Lopez, Eva Moskowitz, Phil Reed, Bill Perkins, Madeline Provenzano, Tracy Boyland, and Allan Jennings - said farewell to the legislative body.

The meeting began with nearly two hours of speeches, as members recounted their efforts over the last four years, said goodbye to the departing members, and offered parting advice.

Speaker Miller recalled how 38 new members took office in January 2002, a few months after the terrorist attacks of September 11th. He praised the council for closing billion-dollar budget gaps and for instituting new lead paint regulations, protecting domestic partnerships, and making emergency contraception more easily available.

"The city is better off now than it was four years ago because of the work of this council," said Miller. "And I know that those who are continuing on will do even greater things."

Several members took the opportunity to remember James Davis, who was shot in the council chambers in 2002. Councilmember Letitia James, who was elected to the seat after his death, said that she thought Davis would be proud of the work of the council to help the poor.

Outgoing Councilmember Bill Perkins used a portion of his time to say "how bad an idea term limits is."

Margarita Lopez focused on missed opportunities, arguing that the council should have passed legislation to create accessible taxis for the disabled.

And Allan Jennings - who was the focus of an embarrassing sexual harassment case and the only council member to lose a bid for reelection his year – offered a farewell promise.

"My parting words: 'I'll be back,'" said Jennings.

NOISE CODE

The major piece of legislation passed by the council was a revision of the city's 30-year-old noise code.

The new code (Intro 397-A):

- Restricts excessive noise from construction sites and allows construction work only between 7 a.m. and 6 p.m. on weekdays.

- Forbids sanitation or other large trucks from operating in residential areas at night.

- Requires bars to keep music below a specific decibel level.

- Allows Mr. Softee ice cream trucks to play jingles ONLY while they are in motion.

- Adds noise from motorcycles, car radios, and portable stereos to the city's regulations.

- And forbids continuous animal noise inside a residence for more than 10 minutes between the hours of 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. or for more than five minutes after 10 p.m.

The regulations also impose new fines - ranging from $50 to $8,000 - for those who break the law.

"This will make the city a quieter, healthier place," said Councilmember James Gennaro.

However, some members said that regulations were rushed through the process and that the council must revisit it in the New Year. "There are too many deficiencies and defects," said Councilmember Alan Gerson.

The noise regulations passed unanimously.

EDUCATION INITIATIVES

The council passed three bills aimed at improving city schools.

One bill (Intro 464-A) requires schools to do more to communicate with parents who are not proficient in English. Report cards, invitations to parent-teacher conferences, and other official notices must now be printed in nine different languages. The bill's supporters said the measure would help students who are most likely to drop out by getting their parents more involved.

"We are leaving the children of immigrants behind at a staggering rate," said Councilmember Hiram Monserratte.

However, some council members adamantly opposed it, saying it was a waste of $20 million that should go to the classroom or other more pressing needs.

"It sends the wrong message that you don't need to learn English," said Councilmember Andrew Lanza.

The council passed the measure by a vote of 35 to 11, with one abstention. Tony Avella, Simcha Felder, Dennis Gallagher, James Gennarro, Vincent Gentile, Andrew Lanza, Michael McMahon, Dominic Recchia, Kendall Stewart, Peter Vallone, Jr. and James Oddo voted "no;" Joseph Addabbo "abstained."

The two other bills require the Department of Education to provide more information to the council.

Intro 619-A requires the Department of Education to report on the average class sizes in each school.

And Intro 550-A requires the administration to provide the council with an account of "temporary" classrooms -- converted offices, bathrooms, basements, and even storage closets that some schools have been made into classrooms to ease overcrowding.

CONTRACTS FOR MINORITY AND WOMEN-OWNED BUSINESSES

The council also aims to give more city contracts to businesses owned by people of color and women.

The legislation (Intro 727-A) requires each city agency to establish a plan to encourage minority and women-owned businesses to compete for city contracts under $1 million. It also eases some requirements set by the Department of Small Business. The Bloomberg administration supports the legislation.

"This sets targets of what we want to aim for," said Councilmember James Sanders Jr. "But it does not set quotas."

The measure passed by a vote of 42 to 5. Simcha Felder, Dennis Gallagher, Andrew Lanza, Peter Vallone, Jr. and James Oddo voted "no."

INTERNET ACCESS FOR ALL NEW YORKERS

In an attempt to improve the availability of high-speed Internet access in New Yorkers, the council voted (Intro 625-A) to create a commission to look the issue.

The panel, whose members will be appointed by the mayor and council, will be required to hold public hearings in each of the five boroughs at least once a year to educate the public on new technologies and to solicit comments on the availability of Internet access in various neighborhoods.

REVISED HEALTHCARE SECURITY ACT

The council also revisited a bill it first passed in August that requires employers in grocery stores to provide their workers with health care insurance. The council amended the measure (Intro 758-A) to ease the regulations for small stores. It now applies only to grocery stores with more than 50 employees (up from 35 in the previous bill).

CHILD WELFARE

The council also passed two measures aimed at improving the well being of children.

Intro 480-A will create task force to investigate the death of any child in New York. Currently, the city only tracks deaths of children who receive support from the Administration for Children's Services. In other cities, such committees have lead to new child safety laws, pedestrian initiatives, and fire regulations.

The council also established (Intro 492) a parent advisory committee for the city's foster care system. It will consist of ten parents from organizations that work on foster care issues, four foster parents, and four parents who have adopted children.

GRAFFITI

The council passed several bills aimed at curbing and cleaning up graffiti.

Intro 299-A establishes penalties for certain commercial and residential property owners who fail to remove graffiti from their buildings and empowers the city to clean it up if an owner refuses to do it. Commercial and residential building owners (of properties with more than six apartments) can be fined between $150 and $300 for failing to remove graffiti within sixty days.

Another measure (Intro 663-A) mandates community service for those caught doing graffiti.

BOATING REGULATIONS AND CRIME IN PARKS

Since the Harlem River has been cleaned up in recent years, more people are using it for recreation, which has raised new safety concerns. In October, Jim Runsdorf, a man who was rowing on the Harlem River, was struck and killed by a motorboat.

The council passed legislation (Intro 495-A) establishing "no wake zones" on the Harlem River to improve boating safety. The city will post signs on the river and distribute information to boat docks in the area.

The council also approved a bill (Intro 470-A) that requires the police department to submit crime reports for city parks and playgrounds.

ENVIRONMENTAL LEGISLATION

The council passed a package of legislation that will require the city to purchase environmentally friendly or "green" products.

Intro 536-A requires the city to purchase faucets, showerheads, toilets, fluorescent lamps and other products with the "Energy Star" seal of approval.

Intro 544-A reduces the city's purchasing of products that contain hazardous or toxic substances.

Intro 545-A requires that paper office supplies, insulation, polyester carpet, restroom dividers, traffic cones, plastic trash bags and other items purchased by the city contain recycled materials.

Intro 552-A reduces the use of cleaning products with toxic chemicals.

And to ensure that the city is following these guidelines and to investigate other ways to reduce the environmental impact of items that the city buys, the council voted to Intro 534-A create an Office of Environmental Purchasing.

"We will use the vast purchasing power of New York City to send a message about what can be done to help the environment," said James Gennaro.

THE NEW YEAR - AND A NEW SPEAKER

The first City Council meeting of the new year is scheduled for January 4, 2006. At this meeting the council will elect a new speaker and approve any changes in the rules that govern how the council operates.

For information on who wants to be the next speaker and some of the reforms that returning council members want, see a transcript of a recent forum with the speaker candidates.

Â

Top 10 Stories of 2005

As 2005 drew to a close, one of the year’s biggest stories continued to unfold. In the early morning hours of December 20, the city’s transit workers walked off their jobs, setting off the city’s first transit strike in 25 years and leaving millions of Americans scrambling to get to work and school.

A transit strike any year would be a big story. But in 2005, the strike stood out because many of the other top stories of the year concerned things that did not happen -- Ground Zero did not make much progress, the West Side Stadium was not approved, the city was not selected as the site for the Olympics, the incumbent mayor was not kicked out, and there was no new terrorist attack in New York, despite such attacks in London and (last year) in Madrid. Indeed, some of the stories with the biggest impact on New Yorkers (or at least on New Yorkers' attention) took place outside the five boroughs -- in Washington, Baghdad, New Orleans, and elsewhere. It was, in reporter’s parlance, a slow news year in the Big Apple -- at least until late December.

One exception was the city’s newsrooms themselves. After New York Times reporter Judith Miller went to jail for refusing to disclose the name of a source, the paper found itself entangled in the investigation of high-level leaks in Washington and all too credulous acceptance of the Bush administration’s reasons for invading Iraq. Over at the Post, Lachlan Murdoch walked away from his job as publisher leaving his father, publishing tycoon Rupert Murdoch, to take up the job once. And Daily News editor-in-chief Michael Cooke has announced he will leave the paper early next year.

Here, not including such news about New York newsrooms, and in rough order of importance, are the Top 10 New York City stories of 2005:

1. Mayor Michael Bloomberg (And Everybody Else) Re-elected

On an Election Day marked by low voter turnout, Republican Bloomberg defeated his Democratic rival Fernando Ferrer by 19.37 percentage points. To help achieve this victory, the billionaire spent $77,894,878 of his own money – or $103 for every vote he got. Ferrer spent about $9.5 million, or about $19 for every vote he got.

On an Election Day marked by low voter turnout, Republican Bloomberg defeated his Democratic rival Fernando Ferrer by 19.37 percentage points. To help achieve this victory, the billionaire spent $77,894,878 of his own money – or $103 for every vote he got. Ferrer spent about $9.5 million, or about $19 for every vote he got.

The defeat represented Ferrer’s third unsuccessful bid for Gracie Mansion. This time, though, the former Bronx borough president made it to the general election after he won the Democratic primary against three other major contenders. On primary night, Ferrer hovered around the 40 percent total he needed to avoid the runoff. Second place finisher Anthony Weiner, who had surged in the final days of the Democratic campaign, said he did not want a run-off, preferring to unify the party around Ferrer (and, some cynics said, ensure his own political future). The final tally showed Ferrer squeaking just ahead of 40 percent, negating the need for Weiner’s grand gesture.

Although the election dominated political headlines, much of the press treated an eventual Bloomberg victory as a foregone conclusion. Many of the city’s leading Democrats abandoned Ferrer, and few issues emerged to capture public attention.

In other municipal elections, all incumbents running again held on to their jobs – except for Allan Jennings of Queens whose tenure on City Council had been marked by accusations of sexual harassment and strange behavior. All the open City Council seats went to Democrats, enabling the party to hold on to its 48 to 3 edge in City Council.

One of the hottest contests came for Surrogate’s Court in Brooklyn, long a bastion for dispersing patronage and wealth to politically connected lawyers. In the contest to fill the seat left vacant after Judge Mitchell Feinberg was removed for misconduct, reform candidate Margarita Lopez Torres narrowly defeated the choice of the borough’s political establishment.

2. Transit Strike And Other Transit Troubles

Members of the Transport Workers Union went out on strike on December 20, bringing a halt to the city’s subway system and buses. The union decided to launch the illegal strike -- the first transit strike in the city in 25 years -- after days of tense negotiations over wages, pensions, health benefits and work rules.

Members of the Transport Workers Union went out on strike on December 20, bringing a halt to the city’s subway system and buses. The union decided to launch the illegal strike -- the first transit strike in the city in 25 years -- after days of tense negotiations over wages, pensions, health benefits and work rules.

With the strike coming during the already busy holiday season, New Yorkers who normally ride mass transit scrambled to find other ways to get around town. The city instituted an emergency plan to help people, but drivers created gridlock on some roads, and riders reported confusion and congestion.

Labor problems were not the transit system’s only problem in 2005. The bombing of three subway stations and a bus in London on July 7 raised new concerns about the safety of New York’s mass transit system. Although the Metropolitan Transportation Authority had approved a $591 million security plan in 2002, at the time of the London attacks it had spent only a fraction of that amount – and that that had gone for consultants and more study. Responding to harsh criticism, the agency announced plans to improve security, deciding to pay defense company Lockheed Martin $200 million for a security and surveillance system at major bridges, tunnels and train and subway stations.

The police instituted searches of passenger bags and backpacks, a move challenged by the New York Civil Liberties Union but, so far at least, upheld in court.

In October, Mayor Michael Bloomberg temporarily increased security and told New Yorkers the subway system was facing a specific terrorist threat. A source in Iraq had reportedly told his U.S. government contacts that several men – some of whom may already have been in New York – planned to set off 19 bombs on the city's subways. Federal officials later determined that the threat had been fabricated.

3. Ground Zero -- Little Progress, Lots of Controversy

Last spring, as planning for Ground Zero faltered once again, one observer wrote, “It’s striking that our parents and grandparents managed to win World War II in 44 months while we have not been able even to agree on a plan for what to do with Ground Zero.”

Last spring, as planning for Ground Zero faltered once again, one observer wrote, “It’s striking that our parents and grandparents managed to win World War II in 44 months while we have not been able even to agree on a plan for what to do with Ground Zero.”

2005 saw some progress. Ground was broken on the transportation hub downtown. The new building at 7 World Trade Center is virtually complete – but has no tenants. And work finally began on the memorial.

But overall planning for the site remained mired in controversy and confusion, with little common ground to be found at what many consider sacred ground.

Last spring, about 10 months after the cornerstone was laid for the Freedom Tower, the building went back to the drawing board after the police department expressed concerns about security at the building. Less than two months later, officials announced a new design. It met the police concerns but removed some trademarks of the original plan -- including the twist in the tower and the openwork at the bottom of the building. The tower will not be completed until 2010 at the earliest and no one knows who, if anyone, will rent space there.

The design problem spurred concern about the slow pace of overall planning for the site. Many blamed Governor George Pataki, saying the he was not paying attention. Perhaps in response, in October, Bloomberg, who until then had largely ignored Ground Zero, stepped into the breach. Challenging Pataki, Bloomberg called for removing developer Larry Silverstein from planning for the site and for building housing, not just office space (which no business seems to want to rent anyway). After his re-election, Bloomberg continued to press his involvement, appointing members of his administrations to the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation.

While some praised the major’s actions; others said he was creating more upheaval. And as he traveled around the country campaigning for president, Pataki vowed to stay involved at Ground Zero, perhaps setting the stage for a power struggle or simply for more inertia.

Also this year, the prospects faded for culture at Ground Zero. The Drawing Center withdrew from the site after families of victims of the 9/11 attacks questioned the political content of its exhibitions. Similar opposition prompted Pataki to overrule his own Lower Manhattan Development Commission and block plans for the International Freedom Center at the site. The decisions left the planned cultural building without any tenants, led many to question the role of the families in planning for Lower Manhattan and raised concerns about whether any bona fide cultural institution could withstand such scrutiny. Ironically, shortly after the museums withdrew, the Port Authority announced plans for a shopping mall near the site. So far, that idea has met with little, if any organized opposition.

4. State Politicians Stop West Side Stadium

After almost four years, plans to build a football stadium on Manhattan’s far West Side came to an abrupt halt in June when the leaders of the state legislature blocked the project. Mayor Michael Bloomberg had proposed and energetically boosted the project, but its defeat probably helped ease his re-election by removing a major argument against him.

The stadium’s supporters said it would be key to the future of the far West Side, would provide a home for the Jets and was essential for the city’s hope for the 2012 Olympic games. But critics challenged the financing of the deal, claiming it was a giveaway for the Jets that would be of little, if any, benefit to most New Yorkers.

In the end, the project also fell victim to the continuing woes at Ground Zero. ''Am I supposed to turn my back on Lower Manhattan as it struggles to recover?'' Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, who represents Lower Manhattan and voted to block the stadium said. ''For what? A stadium? For the hope of bringing the Olympics to New York City?''

5. Nets, Mets, Yankees Plan New Stadiums

|

|

But other projects to provide new and improved facilities for New York teams survived and thrived in 2005.

Plans for an arena for the Nets basketball team in downtown Brooklyn, accompanied by a huge residential and commercial development, moved forward as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority agreed to sell development rights to the Atlantic rail yards to developer Bruce Ratner.

Beyond the stadium, plans for the 22-acre area changed during the year. In July, Ratner and architect Frank Gehry proposed 17 buildings, including some as high as 60 stories. Overall, the project would include as many as 7,300 apartment and, many believe, would transform Brooklyn – for better or worse.

As it has grown ever bigger, the $3.5 billion scheme has attracted more opposition. And before the project can become a reality, the same state panel that blocked the West Side Stadium must agree to support it. Opponents also plan to launch legal challenges.

In Queens, the Jets’ loss became the Mets’ gain. Following defeat of the West Side stadium, the city and the baseball team agreed that the Mets would build a new, $600 million privately funded stadium on the site of a parking lot at the current home of the Mets, Shea Stadium. The city will provide $160 million for infrastructure. If the city had gotten the Olympics, it would have used the new stadium for that – which is what some of Bloomberg’s critics said he should have planned on doing all along.

And once the Mets got a new stadium, the Yankees wanted one too – an $800 million structure, also privately funded, to replace the House that Ruth Built. The new stadium will be north of the current one, on what is now parkland. The city will spend $135 million, and the state about $70 million. The loss of about half of Macombs Dam and John Mullaly parks has spurred some community opposition to the new stadium.

But the largest sports facility now proposed for the city is a NASCAR track on Staten Island that would seat 80,000 people. Although the track would be privately funded and has some innovative features – such as virtually forcing fans to take mass transit to the races – it has attracted widespread opposition among Staten Islanders concerned about its effects on the local economy and on the island’s already horrendous congestion problems.

6. Olympic Bid Fails

After a years of effort, lavish presentations, appeals from celebrities and much wining and dining, New York City’s bid to play host to the 2012 Olympic games failed. In July, the International Olympic Committee awarded the sports extravaganza to London. Among the five competing cities, only Moscow was eliminated from contention earlier than New York.

After a years of effort, lavish presentations, appeals from celebrities and much wining and dining, New York City’s bid to play host to the 2012 Olympic games failed. In July, the International Olympic Committee awarded the sports extravaganza to London. Among the five competing cities, only Moscow was eliminated from contention earlier than New York.

Bloomberg and his deputy mayor – and architect of the Olympic bid – Daniel Doctoroff blamed the city’s defeat on the collapse of the city’s plans to build the Jet’s stadium, which would also have served as the main Olympic venue, on Manhattan’s West Side. But even before the stadium fell through, many observers said New York’s bid could falter due to lukewarm support for the idea among New Yorkers and global antipathy to Bush administration policies. Of course, many of those same pundits also predicted Paris would get the games.

7. Student Test Scores Rise

|

|

City public schools students are doing better in reading and math, according to a spate of test results released in 2005. Third, fifth, sixth and seventh graders saw scores rise on their citywide English and math tests, as, for the first time ever, more than half met or exceeded standards. For example, 77 percent of fourth graders in the city met or surpassed state standards for math, a 9.3 point jump and almost double the statewide increase.

Bloomberg touted the scores as an endorsement for tougher standards, a uniform curriculum and not promoting struggling students. But others questioned any connection, noting that scores rose in other cities in the state that had not instituted such sweeping changes. And there were setbacks too. Most notably, scores dropped among eighth graders, indicating persistent problems in middle schools.

The release of federal scores later in the year added to the confusion. While New York City fared better than many other urban school districts, the scores rose far less than they had on New York State tests. Such results led some to wonder whether students were getting smarter –- or city tests were getting easier.

8. Clarence Norman Convicted

In two separate trials, Assemblymember Clarence Norman, longtime leader of the Brooklyn Democratic Party, was convicted of felony charges arising from his handling of campaign contributions. The convictions came amid heightened concern over corruption in the city’s courts, particularly the selling of judgeships in Brooklyn.

In two separate trials, Assemblymember Clarence Norman, longtime leader of the Brooklyn Democratic Party, was convicted of felony charges arising from his handling of campaign contributions. The convictions came amid heightened concern over corruption in the city’s courts, particularly the selling of judgeships in Brooklyn.

After his first conviction in September, Norman had to resign from both the Assembly and his party post. He faces up to 15 years in prison and awaits two more felony trials.

But despite Norman’s downfall, some questioned whether anything -- other than the player’s faces -- would really change and found plenty of evidence to support their skepticism. Party leaders selected Reverend Karim Camara, a colleague of Norman’s father, to replace him in the Assembly. Geoffrey Davis, brother of the late City Councilmember James Davis who had clashed frequently with Norman, told the New York Sun that Camara’s selection resembled a “Mafia style” selection when “the Godfather goes to jail and picks his successor.”

And the county leaders selected Assemblymember Vito Lopez to replace Norman as Kings County Democratic leader. While Lopez promised reforms, many doubted his sincerity. “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss,” the Daily News entitled its editorial on Lopez. And although Brooklyn District Attorney Charles Hynes has essentially acknowledged judgeships are sold in his borough, he has not yet indicted anyone on charges of doing so.

Faced with such widespread allegations, Bloomberg has said he will make improving the selection of judges a priority in his second term.

9. Fulton Fish Market Leaves Fulton Street

After 183 years, the Fulton Fish Market moved from its old outdoor location along the East River in Lower Manhattan to a new indoor facility in the Hunts Point section of the Bronx. The city first proposed the move in 1999 to bring industry to the Bronx, provide a more modern wholesale fish market and to improve the area around the old market as a residential and tourist neighborhood. Legal wrangling delayed the change, but it finally happened in mid November.

Many saw it as progress, with a sanitary facility replacing what many considered a smelly eyesore. But some had doubts. “The city is throwing away its history," said a fillet man named Bobby DiGregorio, known as Bobby Tuna, told the New York Times on one of Fulton Street’s last days. "One day, there's going to be a Banana Republic where I'm standing."

10. The Gates Come to Central Park

It took 26 years of planning, 5,290 tons of steel and cost as much as $21 million but finally on February 12, more than a million square feet of saffron fabric unfurled from 7,503 steel frames in a wintery Central Park. The Gates -- the work of artists Christo and Jean Claude -- had become a reality.

It took 26 years of planning, 5,290 tons of steel and cost as much as $21 million but finally on February 12, more than a million square feet of saffron fabric unfurled from 7,503 steel frames in a wintery Central Park. The Gates -- the work of artists Christo and Jean Claude -- had become a reality.

The installation of gates of varying sizes positioned along park walkways transformed the park for 16 days at its most austere time of the year. By the city’s account, the work attracted 4 million visitors to Central Park and boosted the city’s economy by $254 million.

There were, of course, naysayers. But many found it entrancing. Calling it a “gift package to New York City,” Times art critic Michael Kimmelman wrote The Gates “is a work of pure joy.”

We can all hope 2006 brings more of those.

Â

Predicting the Big Stories in 2006

“Expect the unexpected,” Assemblymember and Brooklyn political boss Clarence Norman said last year when we asked him to be one of the New Yorkers predicting for us what would happen in New York City in 2005. Norman certainly was right. In the 12 months since he made that prediction,the man who once controlled Brooklyn politics was stripped of his positions, convicted of various felonies and faces 15 years in prison.

Norman was not the only person who proved prescient. Brian Lehrer accurately predicted that Fernando Ferrer would win the Democratic primary only to lose to Bloomberg in the general election. The New Yorker’s Elizabeth Kolbert demonstrated dead-on accuracy when she told us, “With Jon Corzine running for governor in New Jersey and Michael Bloomberg winning re-electing in the city, it promises to be a very good year for political ad buyers.”

But not everyone fared so well. Many respondents thought the West Side Stadium would move forward – or, as writer Kevin Baker put it, “the smug little mayor will get his stadium, wasting billions in needed tax dollars and continuing to wreck the West Side skyline.” And, unfortunately for the mayor, Eric Adams of 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement who Care, missed the mark when he forecast, “Jennifer Lopez will marry her fourth husband, Mayor Bloomberg.” (Indeed, has anybody heard any talk at all anymore emanating from City Hall about J-lo?)

This year, our leading New Yorkers seem preoccupied by the statewide elections and the spreading of luxury condos and posh shops into the outer boroughs. But they touched on other topics as well. When you finish finding out what they think, react to their forecasts or make your own on our 2006 Predictions message board.

Anthony Weiner, Democratic member of Congress from Brooklyn and Queens:

Anthony Weiner, Democratic member of Congress from Brooklyn and Queens:

The Mets will win the World Series and the Democrats will sweep the elections and take back the State Senate.

Gene Russianoff, senior attorney for the New York Public Interest research Group:

On transit;

--The transit fare will not go up in 2006.

--The Metropolitan Transportation Authority will offer holiday fare breaks for a second year in a row.

--Transit officials will pledge to triple the number of trains "right behind this one."(A joke, hopefully.)

On other issues:

--The City Council will come to its senses and abandon plans to extend term limits by their own legislation.

--Hillary Duff will replace Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff

Tom Brokaw, former NBC news anchor:

I hope and expect that the most important story will be the continuing improvement in New York City public education.

Richard Gottfried, Democratic State Assembly member from the Upper West Side:

The most important story in the coming year for the city will be whatever develops in Albany on school funding issue. The elevated anxiety of the state's Republicans should work to the city's advantage, but I don't know what the outcome will be. The '06 elections, particularly for the State Senate, will have a significant impact on Albany. And lots of what Albany does means life or death for the city.

Demetri Martin, comedian:

In the next year, even more will happen than last year. Television will make it so that there is news happening at every minute, and they will make you think that you should not miss it. At least two people will fight over a cab in the cold weather. There will be more bumper stickers about not liking the president.

Andrea Batista Schlesinger, executive director, Drum Major Institute:

Progressivism will become the new patriotism. New York’s middle class will continue becoming the new have-nots. The New York Post will become the new National Enquirer. Insurance regulation will become the new tax cuts. And most importantly, when it comes to being a fresh source of ideas about how to govern fairly and effectively, New York City will become the new Washington, D.C.

Jami Bernard, film critic, New York Daily News:

Uncool is the new cool -- thanks not only to market forces but to the basic oppositional nature of New Yorkers. The boroughs become cool and so does long-neglected Roosevelt Island (really, any place where there's a water view and undeveloped real estate). Small portions of food are in, leading to a rise in a new type of trendy restaurant that serves grazing-style -- good for weight-watching but also a New York response to the proliferation of the Big Gulp lifestyle in the rest of the land and a reflection of the fact that most New Yorkers either suffer from Attention Deficit Disorder of just like saying so in order to get those great meds.

Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz

Those responsible for polluting Newtown Creek will be held accountable for their actions. The plan to restore Coney Island as "America's Favorite Playground" will make waves, and the Parachute Jump will return as Brooklyn's Eiffel Tower when it is lit up for all to see.

The docking of the Queen Mary 2 and Crown Princess cruise ships in Red Hook will ensure that more visitors than ever experience the Brooklyn renaissance.

The Brooklyn baby boom will continue unabated.

The voices of parents and educators will regain their rightful place in the school-reform dialogue.

John Avlon, columnist, New York Sun:

Queens Will Be the New Brooklyn. And so will the Bronx and Staten Island - the resurgence of what used to be called the "outer-boroughs" will continue beyond the now-tony confines of Park Slope and Brooklyn Heights. This will not just be the healthy upside of a city in resurgence, just five years after the attacks of 9/11 - but also the downside of Manhattan's increasing squeeze on middle class and even upper middle class New Yorkers. The spacious apartments, invigorating diversity, and relative calm of the outer-boroughs looks better and better. Whether their modest quality of life improvements can compete indefinitely with warmer and less expensive cities and states is a longer-term issue, which I hope someone in City Hall is strategizing on. With regard to Queens, its status as the most diverse county in the country will be further elevated with the arrival of Carlos Delgado to the Mets.

Elizabeth Kolbert, writer for The New Yorker magazine:

Elizabeth Kolbert, writer for The New Yorker magazine:

Democrats sweep the four statewide offices. Hillary Clinton runs unopposed.

Kevin Baker, author “Paradise Alley,” “Dreamland” and “Strivers”

My prediction is that there will be a major terrorist incident in New York. I don’t say this out of any special expertise, and of course I hope to hell that I’m wrong. But I believe that we must speak now against the day.

In the immediate wake of the London transit bombings, Governor Pataki and Mayor Bloomberg rushed to Grand Central Station, to assure us that we were protected by special, hidden security measures. This was almost undoubtedly a lie, but in any case irrelevant.

Our strategy cannot be to wait for terrorist acts to begin, but to do as much as possible to prevent them from happening in the first place. Anyone who regularly visits our major public places can see that such a strategy is not in place—the few, inattentive, uniformed guardsmen, usually talking to each other; the scant police presence. Meanwhile, major resources are wasted on such ludicrously ineffectual, easily avoidable measures as subway bag searches and van inspections. Without a strong, constant, and vigilant security presence in Times Square, Grand Central, Penn Station, and other likely targets, we are inviting disaster.

Majora Carter, executive director, Sustainable South Bronx and MacArthur fellow:

If we don’t engage about development in the Bronx and coordinate what is actually going on with all these huge projects, what took place in the Bronx during the Robert Moses era will happen again, affecting quality of life, pollution and displacing people. No one is asking any serious questions or following proper planning procedures and the city could end up paying.

Bruce Ratner, developer

It will be a calm year in the sense that the same economic growth, focus on improving education, housing development, and improved safety that we have enjoyed for the last three years will continue. It will be steady, positive growth -- nothing dramatic.

Letitia James, Democratic City councilmember from Brooklyn:

My New Years wish would be that Bruce Ratner finds religion. That he wakes up on January 1, realizes he has done the wrong thing in proposing the Atlantic Yards project, and stands on the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues waving a white flag.

I pray that Marty Markowitz will realize that there are poor people in Brooklyn, and instead of diverting public revenues to build a basketball arena, he decides to build a hospital instead.

I hope that Senator Charles Schumer will recognize that his home could be taken by eminent domain if a developer wanted it.

And I would like the mayor to spend a night in a homeless shelter.

Simeon Bankoff, Historic Districts Council:

1. As all the young renters are pushed out of Williamsburg and Greenpoint, Astoria/Long Island City will officially become the “hot new nabe.” This will last only a year at best before high-rise waterfront development will price out the renting twenty-somethings.

2. New historic districts will be designated in Brooklyn, The Bronx and Queens – but developers will rally against landmarking, particularly in The Bronx. Individual landmarks will be all “safe” bets -- expect office buildings, publicly owned buildings, and perhaps a religious building that’s undergoing restoration. Meanwhile, historic religious buildings and schools will continue to close and be demolished throughout the city.

3. Movie houses will also continue to close and will be the subject of major preservation battles. So will historic hotel interiors as more and more historic hotels get converted to residential use.

4. There will be increased attention from the administration to public art and capital investment in historic buildings, such as schools and fire stations.

5. The city will propose to build a new municipal building as part of the World Trade Center redevelopment.

6. The new façade for 2 Columbus Circle will be unveiled, and be met with general indifference at best. General consensus will be that the building should have either been preserved or demolished. The combination of the new façade, the Hearst Tower and the Time Warner Center will combine to drain all vitality and life out of the Circle like water through a sieve.

7. Stating economic and security concerns and the rising price of gas, the Mayor will propose East River tolls again. This time, with a lame-duck Council, they might even pass.

Eugene Mirman, comedian

Eugene Mirman, comedian

I predict new, fantastic levels of gentrification that will make Bloomberg build an underwater city for the poor. And some bars may be forced to close after unfair fines from the city force them into bankruptcy. Most importantly though, lots more sushi places on the way. Get ready to eat 10 times as much fish, New York!

Paul White, executive director, Transportation Alternatives:

After Mayor Bloomberg finally revokes their privilege to park anywhere they damn well please, thousands of municipal employees stage their own motorized version of "Critical Mass.” Nobody notices.

Adrian Benepe, commissioner, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

It will be the biggest year of parks construction since the 1930s in every borough. And I hope it will be a cooler and wetter summer than in 2005.

Jonathan Bowles, director, Center for an Urban Future:

1. The city’s housing market levels off, but doesn’t burst.

2. Small businesses and immigrants in the boroughs outside of Manhattan continue to drive much of the city’s growth.

3. Congestion on city subways and streets becomes even more intolerable.