Communities across the state have passed legislation banning the controversial practice of hydraulic fracturing. The movement brings up questions of home rule and is being followed closely by the natural gas industry. Cuomo administration efforts to open the New York State section of the Marcellus Shale to drilling will require hydraulic fracturing, which critics say poses a serious threat to the safety of surface and underground water sources, and causes other environmental problems. Advocates of the process say it will boost upstate economies.

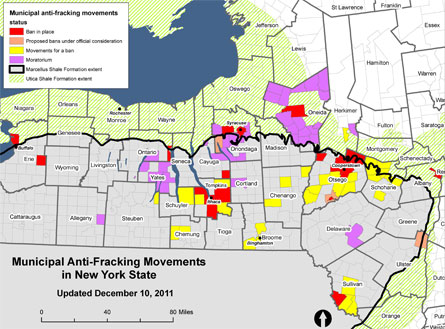

According to a list compiled by Keuka Citizens Against Hydrofracking, fifty-four upstate communities –spanning 14 counties and including the cities of Albany and Buffalo- have permanently banned or placed a moratorium on hydraulic fracturing and related activities within their boundaries. And more bans are on the way. Six upstate counties (Dutchess, Onondaga, Ontario, Sullivan, Tompkins and Ulster) have banned hydraulic fracturing on all county-owned lands. The practice is already restricted from the New York City and Syracuse watersheds.

Local efforts to restrict hydraulic fracturing have resulted in at least two legal challenges to date and these cases are being watched closely by the natural gas industry, upstate communities and environmental advocates. At issue is the concept of "home rule" and whether this extends to a community’s right to determine if gas drilling will take place in its midst.

The Ban in Middlefield

Middlefield Township, which is located in Otsego County and includes part of Cooperstown, enacted a zoning law in June that bans hydraulic fracturing, along with other types of high impact industrial activity.

Town Supervisor David Bliss explained that because nearby Lake Otsego supplies the village’s drinking water and the Susquehanna River sits on its western border, the community felt "substantial exposure" to possible risks related to hydraulic fracturing.

"Middlefield has a history of being forward thinking and a lot of citizens became alarmed. We did a lot of research. That (hydraulic fracturing) was something we didn’t want in our area. The general consensus from surveys and straw polls was that 80% were in favor (of a ban)," said Bliss.

A Middlefield landowner who signed a drilling lease now held by Gastem USA has filed suit against the town. At the first hearing on the case in New York State Supreme Court, Madison County, on December 13th, the judge reserved decision and is allowing further written submissions from parties through mid-January. A decision is not expected until February.

The legal challenge to the Middlefield ban on hydraulic fracturing centers on differing interpretations of state law and the question of whether banning an activity is itself a form of regulation. Levene, Gouldin & Thompson, attorneys representing the Middlefield landowner, argue in a statement released to the press that state law clearly places the authority to regulate oil and gas drilling activity in the hands of the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). They assert that all local bans violate Environmental Conservation Law 23-0303(2), which preempts local municipalities from passing laws regulating drilling activity.

David Clinton, a lawyer for the Town of Middlefield, responds that “state law says we cannot regulate drilling but it does not say anything about whether we can prohibit it. The law is silent.” He cites a 1987 case in which New York State’s highest court ultimately ruled in favor of a municipality that sought to control gravel mining through its zoning ordinance. Says Clinton, “town supervisors across the state are asking about this case.”

Similar legal action has been taken against the town of Dryden in Tompkins County, which amended its zoning ordinance to prohibit hydraulic fracturing and related activities in August. When announcing its lawsuit, Denver, CO-based Anschutz Exploration Corporation also asserted the preeminence of New York State jurisdiction over oil and gas exploration and development. Anschutz maintained that it, “Does not dispute the role of local governments,” but the corporation, “has commenced this litigation to protect its substantial lease holdings in the Town (of Dryden).”

Arguments regarding the legality of Dryden’s actions were heard in Tompkins County Supreme Court in November and now both sides are waiting for Judge Phillip Rumsey’s decision. Dryden’s town clerk, Stephanie Mulinos, points out that the town’s action had "overwhelming support. We held numerous public hearings." Calls to Chesapeake Energy and Cabot Energy were not returned.

Zoning Against Fracking

The DEC does not appear to have taken a definitive position on whether communities have the right to prohibit hydraulic fracturing. Lisa King of the DEC press office said in a written statement to the Gotham Gazette that, "A town can pass an ordinance but we do not know if it will be upheld in court given the current provision in the Environmental Conservation Law that states that local regulation of the oil, gas and solution mining industry is preempted except for local jurisdiction over roads or the rights of local governments under the real property tax law. The scope of this preemption must be left to the courts."

Despite the potential for a legal challenge, advocates report that efforts to pass local restrictions on hydraulic fracturing exist in at least 34 other upstate communities. One of these is the city of Binghamton, whose City Council will vote on a two-year hydraulic fracturing moratorium on December 21st. A restriction on drilling in Binghamton would be noteworthy because of its location in the Southern tier of New York, the section of the state considered most promising geologically for natural gas production. Most of the existing bans on hydraulic fracturing are found north of the Southern Tier.

Local communities wishing to control drilling activity have found allies in both houses of the New York State Legislature. Democratic Assembly Member Barbara Lifton of Tompkins County and Republican State Senator James Seward of Otsego County have proposed similar legislation authorizing local governments to address natural gas drilling in their zoning or planning ordinances. An earlier version of Lifton’s legislation, clarifying that home rule gives local communities the right to regulate drilling, has already passed in the Assembly but did not pass the Senate. Senator Seward introduced similar legislation just before the close of the 2011 legislative session and his bill will be re-introduced in 2012. According to Assembly Member Lifton, “We have a very strong tradition of home rule in New York State. It’s in our state constitution that locals have the power to regulate. If it (home rule) applies to gravel mining, it also applies to gas.”

Advocates Look for Other Ways

Along with bans enacted by local communities, environmental groups are preparing to take the State DEC to court because they say that the agency has not complied with provisions of its own environmental review process. The DEC released a revised draft of its Supplemental Generic Environmental Impact Statement (dSGEIS) for hydraulic fracturing this September. The public comment period on the revised draft has been extended until January 11th, 2012 because of the high volume of comments that have been submitted.

Katherine Hudson, Watershed Program Director for Riverkeeper, told Gotham Gazette that the DEC committed in 2009 to a thorough study of both the positive and negative socio-economic impacts of hydraulic fracturing for upstate communities. She stated that if the final version of the dSGEIS does not include the level of analysis required by the 2009 scope, Riverkeeper and other organizations will initiate proceedings in New York State Supreme Court to declare the DEC review process legally flawed and deficient, which could require the State to re-do the review process and impact statement.

Deborah Goldberg, managing attorney for Earth Justice’s northeast office, adds that “there is a virtual certainty of litigation” against the State. Goldberg cited other flaws in the State’s impact review process, including the drafting of drilling regulations before the impact statement has first been finalized. She also raised measures taken by other states –such as analysis of air emissions data in drilling areas- which could inform New York’s approach to drilling. "We want New York State regulations to be state of the art -- the gold standard."

But first, the State and its local communities must resolve who has the final say about where drilling can even take place. New York’s tradition of home rule faces a test with broad implications for residents statewide.