The Promised Land: A Small Town's Struggle With Hydrofracking

OXFORD, N.Y. — The remains of abandoned farm houses mark the rolling hills and woodlands of the Town of Oxford in the southern tier of upstate New York.

It is here, and in other rural communities in the state, that the most hard-fought regional environmental battle of this generation is playing out — whether to allow the contentious form of natural gas drilling, known as hydraulic fracturing or fracking.

Hydraulic fracturing entails the pressurized injection of hundreds of thousands of gallons of fresh water mixed with sand, lubricants and other chemicals deep below the surface of the earth, in order to “fracture” shale formations and release gas.

Because the shale is located below underground water sources, some scientists —including those affiliated with the City of New York — have questioned whether methane or drilling fluid could be inadvertently released and cause water contamination. Drilling proponents maintain that drilling technology and well construction continue to advance; they also say that fracked natural gas could help the U.S. obtain energy independence.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has signaled that southern tier communities like Oxford may be able to decide whether to allow the practice, even as the state continues a multi-year review of the impacts of hydraulic fracturing in the gas-rich Marcellus Shale and other formations upon which much of New York sits.

This past Tuesday, the small village of Oxford — located within the town of Oxford and alongside the Chenango River between Binghamton and Utica — became the first community in Chenango County to effectively ban activities related to high-volume hydraulic fracturing. But along the way to making the decision, divisions were brought to the fore over the promise that natural gas drilling holds for reinvigorating the tepid local economy and the potential environmental hazards.

Those divisions — between residents, residents and farmers, farmers and other landowners, and even between the village and the town itself — threaten to tear apart the community.

The decisions being made by upstate communities like the Village of Oxford regarding fracking could also have consequences that lead all the way to New York City. Oxford is only 40 miles from the western border of the city's watershed that supplies nine million people — half the state — with unfiltered drinking water.

Though the city has asserted that the watershed is protected through an agreement with state environmental officials that probhibits drilling within it, concerns still remain about how fracking could impact drinking water supplies downstate. The city is also set to increase its dependence on natural gas through the construction of new pipelines that would bring fracked fuel to the metropolis.

The difficulty of deciding whether to allow hydraulic fracturing at the local level is one of the few points on which those opposed, and those in favor of drilling, can agree.

“This isn’t just a risk to one water well," said Oxford landowner and anti-drilling activist Trellan Smith. "This is not a small decision, it’s not a light decision … It’s not a decision that one person can make on their property for themselves.”

Bryant LaTourette, a member of a local group of landowners and a drilling proponent, said: "On something this critical, and this important to our national security, I don’t think that’s a good idea at all." He said the governor had "put everybody on the hook at this time to figure out what it is that the state is supposed to be figuring out. And to come up with our own set of rules and regulations that back if we can do this or not.”

The state Department of Environmental Conservation’s review is focused on the potential impacts of horizontal drilling and high-volume hydraulic fracturing in the Marcellus Shale, which until the technology became widely used was inaccessible because of its depth. The shale stretches from West Virginia and Ohio northeast into Pennsylvania and southern New York. A draft environmental impact statement was released on Sept. 30, 2009. After the receipt of tens of thousands of public comments, subsequent drafts were released in 2011, along with draft drilling regulations.

However, environmental groups maintain that if the state does not release a finalized impact statement to the public by Feb. 13, the agency may be required to re-start the review process. The state health commissioner has also been charged with reviewing existing studies related to public health impacts from hydraulic fracturing.

A SMALL VILLAGE DEBATES FRACKING

The village of Oxford, population 1,700, advertises itself on its website as "a community of beautiful old homes, churches and well-kept parks." There are arts-and-crafts galleries, a folk music center, a golf course. "The surrounding countryside is a haven for everything from White-Tailed deer to Pheasant, Turkey and Geese, and our streams, lakes and rivers provide some of the best sport fishing in NY state," the website reads.

The bucolic village is a jarring setting for an increasingly impassioned, complex debate over U.S. energy policy, environmental protection, local economic development and how responsibility for the public’s welfare is shared — or not shared — across jurisdictions.

The newly passed “ban” on hydraulic fracturing in the village, which was enacted by the village planning board with a super-majority vote of four-to one, is actually an amendment to the local zoning code, clarifying that gas drilling-related activities are not permitted in the village. The village’s first attempt to pass the ban was rejected by the county planning board, which had raised a number of questions, including how it could impact the regional economy. The village's mayor has asked for clarification from the county board.

It remains to be seen whether bans like the village's can survive legal challenges from property owners or larger jurisdictions.

LaTourette claims 68 percent of the land in the greater town is already leased for drilling. Another 20 percent could eventually be leased as well.

The village's decision also conflicts with the stance taken by the Town of Oxford, which amended its zoning laws to permit hydraulic fracturing.

Village of Oxford Mayor Terry Stark said that the village planning board took action because the impact of any local ground water contamination would be felt most deeply there,due to the concentration of residents. At the same time, Stark acknowledged that he could not control drilling in the larger town.

“I’m simply trying to run a process that gives everybody an opportunity to be heard,” he said.

The village initially passed a moratorium on drilling in the fall, which Stark said he had hoped would give all sides a chance to look at the issues and reach some common ground. But Stark said that it became clear that a clarification of the zoning code itself was necessary in order to respond to possible lawsuits from landowners.

"I didn’t do this to pick a fight," he said, adding that he received a petition with over 300 signatures of the village's 1,000 possible voters that said hydrofracking within the village was "not compatible with what the village should be."

Some in the greater town have pushed for a 24-month moratorium on fracking.

A group of Oxford residents say that so far they have collected signatures from at least one-third of the town’s adults (and almost half of the town’s registered voters) supporting the idea. One member, Trellan Smith, stressed that, to date, the group had only canvassed half the town’s adult residents. The signatures were presented to Town Supervisor Lawrence Wilcox on Nov. 1, 2012.

In a recent interview, Wilcox said that the town was waiting for the DEC to release its final environmental impact statement and drilling regulations before making a determination on how to proceed. Chenango County records show that Wilcox has a gas lease with Norse Energy that was renewed in 2009. Wilcox is also chair of the Chenango County Board of Supervisors.

Asked if having the gas lease posed a conflict-of-interest, Wilcox said that the town attorney had advised that if town board members who had land leased for drilling were to recuse themselves from the decision, there would be no quorum.

“The positive things that safe gas exploration could bring to upstate New York are phenomenal,” Wilcox said. But, he said he was still awaiting the results of the state review. “I don’t want to have it unless it can be done safely. That’s the feeling of most of the community. They don’t want to see the land ruined.”

DRILLING TO SAVE THE LOCAL ECONOMY?

Chenango County, where Oxford is located, had the fastest private sector job growth in the southern tier between 2010 to 2011, largely due to a spike in manufacturing. Much of that is because of the boom in demand for Greek-style yoghurt produced by Chobani, which has a large facility in New Berlin with 1,200 employees.

Nevertheless, it remains a largely rural county, with agriculture still the number one industry, according to Donna Jones, director of planning for the county. The 200 or so mainly dairy farms in Chenango are about half the number that existed there in the 1970s and 1980s. Per capita income in Chenango is $22,500, Jones said. Fourteen percent of residents live under the poverty line, mirroring the state.

“It's very difficult for farmers to make a living,” explained Jones. She said the loss of manufacturers like Proctor & Gamble had walloped the economy. “We desperately need a boost,” she added.

How much wealth for upstate localities could be unlocked by drilling in the Marcellus Shale? To put it in perspective: Estimates of the amount of gas that exists within the formation range from 84 to 489 trillion cubic feet. State regulators say New York uses about 1.1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas a year. A DEC analysis in 2011 found that “over the 30-year life of a typical horizontal well, a total of $1.45 million in (local) tax revenue could be generated.” The state has estimated that as many as 40,000 wells could be drilled.

Jones said that the Village of Oxford was within its rights to restrict activities related to hydraulic fracturing in its boundaries. “They have the right but they still have to have it reviewed.” But a pending court decision on similar bans enacted by the towns of Dryden and Middlefield could have an impact on the ability of other upstate communities to restrict drilling.

The county rejected the village’s first attempt to ban hydraulic fracturing — in part — “because we were looking at it regionally.” Jones added, “We’re going to see how this affects the county.”

She said that home rule gives local municipalities the power to put regulations in place that will protect their town or village.

Residents on both sides of the fracking debate see the importance that gas drilling could have to the local economy. Some drilling proponents say the opposition is coming from newer residents, and advocacy groups with financial ties to New York City.

“We’ve struggled with this area for a long time now economically," said Will Bradley, a local landowner who supports permitting hydrofracking. "Why does NYC have so much control over upstate? We would just as soon they didn’t … Benefit is not infinite, and risk is not zero."

Referring to the ongoing state DEC review of hydraulic fracturing, Bradley said, “Part of what we’re dealing with here is people that are not willing to accept that (state review). That’s part of the division in the village and in the town. ‘We don’t trust the state. We don’t trust the [city’s Department of Environmental Protection]. We don’t trust the DEC. We don’t trust anybody. … That’s what’s tearing people apart here.”

For Mina Takahashi, who maintains a small organic farm in Oxford, the question of water safety was what first led her to join with other residents in opposition to hydraulic fracturing.

“We irrigate with stream water, we cultivate our mushrooms with stream water, we have a spring well that’s up in the woods that we also drink from … If you have animals you have to water them — you’re going to use what you have … If your water is contaminated and you’ve got a hundred head, what do you do?” she said.

Oxford already has experience with low-volume hydraulic fracturing. Landowner Paul Romahn, who also sits on the town’s planning board, has a well on his property that he says was fracked once in the mid-2000s. He said the drilling company was on his land for seven days of extraction, and that he had his wells tested afterward.

“All the tests came back perfect," he said, looking out at his herd of cattle. "This spring I had the water tested again — there was no contamination. When they were drilling, the cows were in this field, watching the operation.”

Romahn explained that his 5,200-foot well was vertical, not horizontal. Eighty thousand gallons of fresh water were needed to frack it. The type of drilling that is currently under review by the state entails horizontal drilling below ground, and a significantly higher volume of fracking fluid.

Romahn noted that not all of the drilling fluid had been pumped out of his well. “Give me an industry that doesn’t have any type of pollution," he said.

A QUESTION OF CONTROL

An issue of great concern to Oxford property owners on both sides of the drilling question is the degree of control that they have over their land now that companies have leased the mineral rights of most of the town.

State law enforces the concept of compulsory integration, which means that once 60 percent of a “spacing area” is leased for drilling, all mineral rights in that spacing area are available to the drilling company, whether property owners consent or not. LaTourette and other landowners said that all property owners have the right to enter into an agreement with the drilling company to share in royalties, and new wells would not be drilled on the remaining forty percent without an owner’s consent. But owners cannot restrict access to their property via below-ground horizontal drilling.

John Knapp, who operates a local woodworking company, said he regrets his decision to lease the mineral rights on all 268 acres of his property to Chesapeake Appalachian in 2007. Knapp said he received a one-time payment of $35,000, and that the lease on his property had just expired. But he has since learned that making sure that his lease is not automatically renewed could be complicated.

“Hopefully I’ll get out of it.” he said. “It gets very confusing for someone like me … You feel like you’re alone when you come up to these big companies — you feel like there’s nothing you can do. To me, this is a life or death situation. I don’t want to move.”

Norway-based StatOil, which Knapp says now holds his lease, confirmed that they “bought into” one-third of Chesapeake’s Marcellus Shale holdings in 2008. StatOil referred questions on New York State operations to Chesapeake.

A representative for Chesapeake did not respond to questions about its New York holdings.

WAITING FOR AN ANSWER

More than 150 upstate communities had enacted moratoria or bans on hydraulic fracturing as of Jan 24, according to Fractracker, a project which collects data on local actions relative to drilling. Movements for some sort of a prohibition exist in 92 other upstate communities — including 11 in Chenango County. Fractracker also reports that numerous New York communities have passed resolutions indicating they are open to the practice. Fractracker’s map of these communities does not indicate a total number, but there appear to be at least 40.

As hundreds of communities wait for a signal from the state, New York stands at a historic juncture. Mayor Stark commented that gas development will have a “very dramatic” effect on the region, especially if it means “thousands” of wells across upstate New York.

“They do affect the nature of the rural character of the area when you have that many of them for such a long period of time," he said.

Abbie Tamber, who owns five acres in Oxford, was an early member of the Central NY landowners coalition, a pro-drilling group, but then left to join the opposition.

Tamber said that the original steering committee of the coalition was ousted two to three years ago. She said land speculators were now dominating the group. "Unfortunately, it's going to come down to greed," she said. "It's not about jobs. And, it's really not about farmers."

She said that concerns about water safety have made her fundamentally opposed to hydraulic fracturing. “We don’t know what’s going to happen," she said. “You can live without fuel. You can’t live without water.”

_____

Image of land leased for natural gas drilling in Oxford, N.Y. Photo credit: Sarah Crean.

State Lawmakers Weigh Options For Hurricane Sandy Relief

ALBANY, N.Y. — A house disemboweled by flooding, a boat in the middle of a normally busy road, boilers and basements under water, a boardwalk blocks from where it normally stood.

While normal life has returned to some sections of the city, these images are still seared into the minds of residents of parts of Queens, Staten Island, and Brooklyn, and for others the destruction wrought by Superstorm Sandy is still physically inescapable, forcing them to live without power, heat, a regular place to sleep or in homes infested with mold.

“If you don’t live in these impacted communities you just wouldn’t know what it is like,” said Republican state Sen. Marty Golden, who represents parts of south Brooklyn that were hard-hit by the storm. “People living just two miles away from some of this have no idea what the conditions are. Sandy has not left us and she is going to be around for a long time.”

Golden is a member of the State Senate's Bipartisan Task Force on Hurricane Sandy Recovery, which could release details on a package of legislation Monday aimed at helping residents still reeling from the storm. Legislators are keen to start delivering money to rebuilding efforts so they can show their districts that they can bring home badly needed relief funds, especially with state budget negotiations moving faster this year and President Barack Obama recently signing $60 billion relief bill.

In exploring their options, legislators say have they focused on marshaling services, resources, specialized labor and insurance experts to boost rebuilding efforts and to get people back to normal faster. Proposals would eliminate sales tax on cars and home building materials for Sandy victims.

There are also a number of programs designed to help Sandy victims that legislators want to see extended. They include an informal program announced by Cuomo where New York-chartered banks and other participating institutions can give homeowners in areas impacted by Sandy a break on their mortgage payments. Another instituted by the Internal Revenue Service allows Sandy victims to borrow from their 401k without penalty to, as Golden says, “allow them to get whole again.”

The task force toured communities in Brooklyn and Staten Island on Thursday in an effort to get a sense of the scope of Sandy’s lingering devastation, which is not obvious when just looking at the numbers — but the numbers are still staggering; 305,000 homes damaged or destroyed, displacing over 40,000 in the NYC area alone, and impacting over 265,000 businesses. “We need a plan,” said Golden. After the tour, the members of the task force held a roundtable discussion with labor and community leaders, politicians and first responders.

“We intend on putting together a comprehensive package of legislation,” said Sen. Jeff Klein, head of the Senate’s Independent Democratic Conference and a member of the task force, at Thursday's hearing.

The task force formed in the wake of the announcement that the IDC would be joining forces with the Senate Republicans to keep Senate Democrats from taking control of the chamber despite what at the time looked like a numerical victory.

At Thursday’s meeting of the senate task force, Sen. Diane Savino described just how damaging Sandy has been for businesses to her district on Staten Island. “One of the things that gets lost,” Savino said, “is the impact the storm also had on the north shore. Most people don’t realize what the impact of our industrial waterfront has been tremendous. We’ve got businesses that have been put off-line — who can forget the picture of that giant tanker washed out on to Front Street? So, the damage has not just been to residential districts, it’s also been to our business districts."

Golden said that he is particularly concerned with those who have been mentally and financially traumatized by Sandy and don’t know where to go for help. “Who knows how many people have had mental breakdowns," he said. "Who knows how many people are in the stages of bankruptcy. We need to give them the appropriate help to keep them afloat but they need to know to reach out to us."

Democratic Sen. Joe Addabbo, whose Queens district was one of the hardest hit by Sandy, has a list of concerns of his own — some of which are unique to Queens and others that are all too common across the areas impacted by the storm.

“I still have over 7,000 homeowners in the Rockaways without power,” Addabbo said. “There are those homes in Breezy Point that haven't been rebuilt, homes across the district that need rebuilding. There are some businesses that will never come back but there are some mom-and-pop stores that gotta come back for the fabric of the community, and we gotta help them. The money from the bill that the [US] Senate just passed can't come quick enough. It has been three months."

Addabbo has cosponsored a bill put forward by Sen. Daniel Squadron that would give property tax relief to Sandy victims. Addabbo is working on legislation that would give small businesses a small amount of cash to restore their storefronts.

Perhaps the most common concern among legislators is that residents will simply pack up and leave — they suspect that a number of them already have. Golden noted that it is hard to tell just who has abandoned their properties since the storm. “I don’t think we know quite yet how many people have just walked away,” he said.

They say they also must find a way to make sure that rebuilding is not cost prohibitive.

"You know, we have residents who went through Hurricane Irene two years ago and they were just paying off their loans from that and then Sandy hit,” Addabbo said. “Now they are being told they have to raise their house ten feet, or pay thousands in flood insurance. We don't want everyone to pack up and leave. We don't want a flight out of southern Queens."

While state lawmakers consider their options for helping them to rebuild, New Yorkers face a barrage of information about where and how they should — and if they should at all. Last week, the federal government released a draft version of new flood maps for the city that show thousands of homes in harm's way. These homeowners could now be faced with prohibitive flood insurance rates.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg issued an executive order Thursday waiving standard zoning rules to allow homeowners rebuilding in those flood zones to build their homes higher and out of range of floodwaters.

The mayor also adopted a new rule to require a minimum flood-proofing elevation — a move designed to make houses safer and to also possibly lower federal flood insurance premiums. Cuomo, for his part, integrated a plan to buy out residents of shores and flood zones into his budget, saying, “Maybe mother nature doesn’t want you here.”

Both Golden and Addabbo say they have heard from some residents who are interested in the program, but they are also worried about helping those who want to stay.

“I gotta think most residents are saying, 'I chose to live by the water. I want to live by the water.' So we have to help these people meet the requirements that the flood maps dictate and help them financially to make sure they are in compliance," said Addabbo of Cuomo’s proposal to buy out residents.

___

Image of Sandy destruction at Howard Beach, by Pam Andrade, used under Creative Commons license.

A Shrinking Footprint: Geophysicist Klaus Jacob On Rising Sea Levels, Sustainability And Indian Point

NEW YORK — In this post-Superstorm Sandy era, geophysicist Klaus Jacob is regarded by many as something of a seer.

But in his view, the public debate over climate change and what it means for the city has wrongly been focused on extreme weather, and not on the rise of sea levels that will reshape the footprint of the metropolis.

In the second part of Gotham Gazette's sit-down interview with Jacob, the climate change expert speaks about the city's energy policy, long-term planning for sustainability and why he thinks Indian Point nuclear power plant needs to be shut down.

Jacob was interviewed at at his office at the Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y., in late December.

Need to get caught up? Read the first part of Gotham Gazette's interview with Jacob here.

GG: So you’re saying that New York City’s density patterns will have to change because of our shrinking footprint due to sea level rise?

KJ: The housing density patterns of the city will have to be totally changed. When you look at the patterns of our population changes from the 2000 to 2010 census (he refers to a map on his computer screen) there are blue areas where there was a population increase. And red areas, where there was population decrease. Where are the blue areas? On the waterfront, mostly on the west side. Areas like Chelsea … Really got built up on the waterfront … All in the A zones, and A overlapping on B.

Where are the red zones? Washington Heights. Midtown. There’s one little anomaly, which is around the WTC. That is red and we know why. But that’s a temporary blip. In the next decade it will probably become quite blue — from 2010 to 2020 — because it will be re-occupied, both business-wise but even residential … It (density) goes up in the wrong places, and it goes down in the wrong places.

Brooklyn Heights will become prime real estate. Morningside Heights, Washington Heights ... Our graveyards up in Queens, Brooklyn, Prospect Park, Central Park will be prime real estate. Not that I am saying we should do away with those. But the surrounding areas will be prime real estate.

GG: If you had to make any type of projection — what do you think the city’s next move will be regarding planning for climate change?

KJ: There’s some pretty smart people in the Department of City Planning. There’s been some unfortunate personnel changes in the Office of Long Term Planning over the last year from which they had to recover. They’re all working for the mayor. They can advise him, but they don’t make the decisions, they can only make recommendations. But it is easy sometimes to forget the long-term vision in the day-to-day pressures of decision-making, but ultimately they are well intended.

I sit on a DCP technical advisory board, and I always stress long-term vision … I’m going very strong on that ... I have no power, except the power of the mind. The other people have the real power.

DCP has a HUD (sponsored) project that began way before Sandy, in which DCP assesses how to plan for the waterfront of NYC. How to make a plan, NOT for tomorrow — but rather for some time into the future. That’s in the works … Sandy … provided (data for the study) that actually wasn’t available before. Once that (plan) gets accepted by the mayor, it should influence the Department of City Planning, the Department of Environmental Protection, the Department of Buildings …

GG: How does the city’s energy policy relate to planning for climate change?

KJ: Upfront, I should say I’m not an energy expert. I have limited knowledge and some opinions but they are not expertly based. They are more common sense-based. I’m also on the board of Scenic Hudson, where we occasionally discuss relevant energy policy.

In general, the greening of the city is making relatively modest positive progress. But I would call it modest. It’s not as aggressive as one could be. (Utilities) still behave in a very traditional way. They certainly are not up to sea level rise and climate change. They still look at their traditional distribution system. We are far away from a smart grid for NYC.

That is not to say that there aren’t many buildings that come online in NYC that are LEED certified. But that’s pretty much within the realm of what the owner wants to pay for and do. The city encourages it, but the building code doesn’t necessarily have the teeth that it would need to push all these measures through in a much more accelerated way.

Again, this is slightly outside my expertise. This needs to be verified and checked.

I think the city could be more aggressive on the energy side. The governor has a plan to shut down Indian Point, which personally I think is a good idea. There are plans to create new power transmission to NYC by laying a DC line in the Hudson, through Lake Champlain, all the way up to Quebec … to get cheap waterfall hydro-electric power into NYC with a DC-to -AC converter station, probably in Yonkers. From then on, it would be traditional power distribution into the Con-Ed grid.

That new source would replace a good chunk of Indian Point in terms of its normal production. There is still a need for peak time additional resources if we don’t change our use pattern. You still see all of the skyscrapers lit up in the night. Do you want to see black skyscrapers, or visible skyscrapers? It’s not very green to have all those visible skyscrapers in the night. Would it change the character of the city? Yeah, it would. But what is more important? This is something that hasn’t been discussed much. Is Times Square the right thing to do?

There’s all sorts of stuff that could be changed to make it a greener city, but it would be a darker city. So the question is, how can we make the city greener and have a little bit of light for our joy and amusement and for businesses.

We have changed water use in NYC heavily by metering individual households in buildings that before had just one meter for all. Water usage over the last ten years has gone down incredibly, which saves NYC on the infrastructure side since it doesn’t have to provide new capacity for the next million people … (by bringing) new water supply into the city.

We could do the same thing on the electric side. In many cases, consumption of a large building is just divided by the number of households … It’s buried in the rent, not on an electric bill. If we could find means and ways to charge people for what they’re really using, including inside skyscrapers … And maybe put a city tax on electricity. And then use this tax to do smart urban planning and relocation of populations. A cap and trade policy on a city basis. Which of course you can’t do, because everything has to be approved up in Albany. And we know where congestion pricing went.

GG: When Gotham Gazette interviewed Deputy Mayor Cas Holloway, he told us that natural gas would be part of the city’s energy strategy for the indefinite future.

KJ: It’s true that natural gas is a better fuel than coal, or diesel or fuel oil that we burn in our furnaces and boilers … In the first two to three minutes there’s this incredible black smog coming out. That wouldn’t happen with natural gas. It’s more efficient and whether we like it or not for the time being, an abundant resource. I don’t trust the governor that he will clamp down forever on the fracking situation.

Holloway is probably unfortunately right on that. I say unfortunately because it feeds our fossil fuel addiction. We have to get away from that kind of energy addiction. If we would spend as much money on a smart grid with photovoltaic cells and other energy resources, (or) getting full usage out of the methane from our dumps, as on allowing for conversion of heating oil to natural gas ...

GG: How is the city policy on waste?

KJ: Our waste policy in this city is totally off the mark. Every waste. One-third of the waste in NYC is construction-related. That should not be exported. That should be handled like the Japanese do it. It’s a resource. They grind it up, steel, concrete and all, and form it into bricks and make new ground. We need new ground here. The only areas that stick out … above future flood zones (are) … a dump that’s not far from Kennedy Airport … and Fresh Kills on Staten Island. That will be extraordinarily valuable high land … It’s an engineering and planning issue. We should not export our construction waste to PA. We badly need it inside the city ¬—to make landfills, high grounds, for the future.

GG: Back to what you said before, why aren’t we investing as much in smart grids or harnessing methane from our dumps — as we are in converting to natural gas?

KJ: That’s a rhetorical question. The city doesn’t really control its energy policy. It’s done by the utilities. The city can only change the building code. And to the extent that buildings have a difference in their energy usage, it (the city) can influence the energy policy. It can try to influence the MTA, even though that’s not a city agency, whether they have hybrid buses or not. That influences the energy footprint of the city. There are many things that the city is not in control of.

GG: But the city is facilitating construction of the Rockaway pipeline; they are moving bureaucratic hurdles.

KJ: Yes. Where the city can have influence, it moves it. But it’s limited, and it has to happen not just on the city level, it has to happen on the state level. The Public Service Commission has a lot to do with it. Even if Con-Edison or LILCO wants to do something, they have to go to that commission upstate and say, “can we turn that into an add-on on the utility bill that we charge our customers?” Unless they get that approval, it won’t happen.

There’s so many institutional hurdles. The mayor has the power of the pulpit. He can talk to the governor, to the federal energy commission. That’s where the influence is. The city can make its own buildings efficient, and make public housing efficient. But these are the few things that the city really has direct control over.

It’s such a multi-layer, jurisdictional issue. A lot has to do with institutions. The city could do much better on city planning. All of these developments that are still in the pipeline —Willets Point, Hunters Point. There are these blunt instruments out there — the SEQR (State Environmental Quality Review), the Environmental Impact Statements, where developers are asked to consider certain guidelines. That’s not a good policy instrument because … You have to oblige only existing regulations based on past experience, not regulations that deal with future conditions. There’s no requirement that you have to take sea-level rise into account.

The city finally insisted that a few feet (be added) in certain areas to the old FEMA regulations … Timid attempts to deal with all of these issues. And, on the energy sector, there’s a limited impact that the city can have on the energy realities.

The state can influence how cheap natural gas will be in terms of this fracking business, which I have professional problems with on the earthquake side. The waste water, when re-injected into deep, geological formations — that will come from gas production wells made feasible by fracking — can trigger damaging earthquakes. But in addition, I am fundamentally against it because it fuels our fossil fuel based energy addiction, rather than pushes us toward energy conservation, efficiency, a smart grid, and alternative energy.

GG: But given what’s happening with climate change, why is the city not willing to be more aggressive in moving away from fossil fuels?

KJ: There are individuals in the various city agencies that are champions, but then there’s the rest. Ourselves, together with engineers are very traditional folks ... As long as it’s not in the building code, the ASCE regulations, the International Building Code, nobody has an obligation. It’s left essentially to the owner and to the pulpit of the mayor to convince people to go beyond the codes. Codes are minimum values — they are never reasonable values — intended to provide just minimum safety. Not desirable safety, not desirable energy efficiency.

GG: This seems to tie back to what you were saying before — that the fundamental practice of the city is 10 to 20 years behind the science.

KJ: I’ve been working for 10 years on the seismic building code for NYC. It was a wonderful eye-opener. I understand now why that process takes so long. Everybody wants to have their opinion in there, including the real estate board. We initially thought that we could get something through about retrofitting (existing) structures for the seismic building code, but it was very clear that the real estate board would not go for it … There is a one trillion dollar building inventory and a trillion dollar infrastructure … A lot of assets that you have to deal with.

GG: When will the NYC Panel on Climate Change meet again?

KJ: The Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning is in charge and has set a new schedule for it.

GG: Presumably that office will exist after Mayor Bloomberg’s term ends?

KJ: Yes… and the City Council embedded its task into permanence, but it is still driven by individuals on a day to day basis, what’s a priority, what is not a priority…

Any personnel change can set back an agency. It happened with the MTA- they have gone through three CEO’s... Jay Walter left one month after Hurricane Irene … Joe Lhota (who has since left office to run for mayor) had to learn everything from scratch … His staff probably briefed him damn well on what to do for Sandy … He whipped that agency into shape. Luckily there was a lot of pre-Sandy planning, including my own study.

But leadership changes can set an agency like the MTA back politically. The findings (from Jacob’s study on potential MTA climate change adaptation measures) that were delivered internally to the MTA, and publicly to everybody — to the best of my knowledge — never went before the board of trustees. Therefore it never went up to Albany, neither to the Legislature nor to the Governor. If the MTA doesn’t ask for money up there for climate proofing, they can’t take it out of their existing budget to retrofit. There is always more pressure from the public to buy new subway cars, beautify subway stations …

The (recently rebuilt) Battery Park (South Ferry) subway station is totally useless in terms of climate change. Total mis-investment, and many of us told them so, that this is ridiculous. Same thing with the 2nd Avenue subway. It’s fine as long as we are in midtown but … The new downtown Nassau Street station will be in the flood zone. That phase (3) has not yet been financed but the plans are ridiculous. Two stations — new, planned stations — that will be in existing flood zones, so far without protection planned in.

That came up in the MTA blue ribbon commission in which I was raising hell as an observer. I said, “you’re not dealing with the elephant in the room … sea level rise and climate change and all your plans ... But what about the tens of billions of dollars that you have to spend in fixing up your subway system?”… I made a presentation (at the next meeting) and there was silence in the room. It was someone on that blue ribbon commission who agreed, “I opt for a chapter on adaptation to be included in the commission’s report.” Before that, it was all about mitigation in the climate sense; greening, water use, energy, reducing heat island effects … But not adaptation to sea level rise.

I was asked to write the chapter on climate change adaptation. It’s on the books of the MTA, all these recommendations. But the MTA fell terribly behind in the first year and they have never kept up with the recommendations, at least in part, because the board was never confronted with it.

GG: The media presents the MTA’s performance during and after Sandy as something akin to a miracle.

KJ: And rightfully so, in terms of response to the storm. But few covered the real consequence and fallout from all the state-sponsored research — we haven’t changed our risk profile. Our vulnerability is exactly the same as it was five years ago — or even three months ago. Irene should have been the wake up call, and it wasn’t at the MTA, perhaps because of the change in the CEO.

Sept. 11 threw the whole nation back on natural disaster preparedness by about 10 years. You couldn’t talk to FEMA, the Department of Homeland Security about earthquakes, climate change, floods. It was all about terrorism … Who could care about a Sandy coming? That’s the reality. Bin Laden did considerable damage to this country — institutional damage.

GG: Can you talk more about your research on Indian Point?

KJ: We had an earthquake in Virginia in August, 2011 and assessed recordings from a nuclear power plant in the vicinity of that earthquake; they need to be applied as a shaking level to Indian Point to see what could happen. In the mid 1990s we did a study of the Tappan Zee Bridge and provided synthetic ground motions for magnitude 5, 6, 7 earthquakes at various distances from the bridge; they also need to be applied to Indian Point in terms of the dynamic analysis of the structure. I am also concerned about stored fuel on the site which is not protected by any concrete eggshell structure.

The last point is that the guidelines of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission are that a reactor meltdown should have an annual probability of lower than 10 to the minus 6 per year —one in one million chance in a given year. For this you should at least take into account any natural hazard, with an annual probability of 10 to the minus four, or an event with a chance of one in 10,000 in any given year.

If you were to take such a hazard, say a storm surge, a 10,000-year storm surge, in the Hudson River that comes up from the Harbor, then I believe you could potentially be in trouble … I want to see that calculation done. I believe (although I don’t know this for sure) the Indian Point control room is at 15 feet elevation. The Sandy surge was 10, 11, 12 feet. Three or more feet for a 10,000-year surge could get you into trouble.

I don’t know that for sure but I want to see the study done for the 10 to the minus four storm surge passing by Indian Point, and see whether you have control over your standby power that controls the cooling of the nuclear reactors so you don’t get a Fukushima scenario.

GG: Do you believe that Indian Point should be closed?

KJ: Yes. I was not for closing it — suddenly — in the past, but I always said, “no extension of the current licenses.” By the end of 2013, for Reactor #2; 2015 for Reactor #3, that’s it … This 10,000-year storm surge is of concern to me … We are essentially operating a plant where we have requirements on the books in terms of safety that were never fully researched or enforced.

GG: Finally, is there anything that you want to say — relative to climate change — that we haven’t discussed?

KJ: We must not do anything that would produce avoidable risk to future generations. That’s the guiding principle. It’s environmental justice in a way, inter-generational environmental justice. Just like we have environmental in-justice right now. We are creating a problem for future generations, as we have done with greenhouse gases … We shouldn’t add to that burden.

Now you can translate that it into all sorts of details, like developments on the waterfront. We will live to regret this. They (future generations) will have to pay to remove this misplaced junk in the water, and move to higher ground, when we could have done that right now.

____

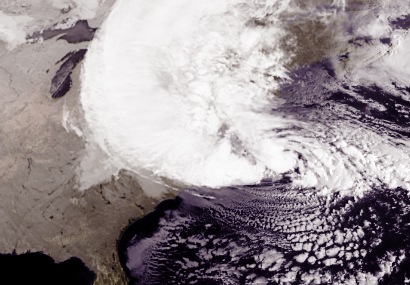

Image of Hurricane Sandy at night courtesy of NASA.

Storm Surge: An Interview With Climate Change Expert Klaus Jacob On NYC's Post-Sandy Future

NEW YORK — Geophysicist Klaus Jacob has been warning about how vulnerable New York City is to violent weather for years and, more importantly in his view, how climate change and rising sea levels will transform the shape and character of the metropolis.

Weeks before Superstorm Sandy shocked the city and upended the public discussion about preparing for future extreme weather, The New York Times published an interview with Jacob in which he said that the storm surge from Hurricane Irene came only a foot from paralyzing transportation in and out of Manhattan.

“We’ve been extremely lucky,” Jacob told the Times. “I’m disappointed that the political process hasn’t recognized that we’re playing Russian roulette.”

Now, in a sit-down interview with the Gotham Gazette, Jacob describes his struggles to get Washington and Albany, as well as the city, to pay attention to the peril of rising sea levels; how some proposed solutions like flood gates would likely cause more trouble than they are worth; and how he thinks the city's shrinking footprint will lead to more densely populated neighborhoods on higher ground and the loss of coastline.

Jacob became interested in New York City issues in the late 1980s when he successfully prodded local leaders to adopt a seismic building code. Since the late 1990s, he has worked largely on climate change, focusing his attention on how the rise in the sea level and storm surges will affect New York and other global cities. Mayor Michael Bloomberg appointed him to the New York City Panel on Climate Change, which was convened in 2008. Jacob has served in an advisory capacity to city and state agencies on issues related to climate change.

Jacob’s own home, next to a tidal stream and marsh close to the Hudson River, was flooded during Superstorm Sandy’s historic storm surge.

He was interviewed at his office at the Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y., in late December.

This is part one of a two-part interview. The second part will be published next week.

GG: What are some of the lessons that you think can be derived from Sandy? What are you focused on as you’re moving ahead in your work?

KJ: There is clearly already visible action that [the Federal Emergency Management Administration] has taken. FEMA is in the process of putting out so-called Advisory Base Flood Elevation maps … the 1 percent per year probability flood insurance rate maps. That is a much needed revision — since the last time those maps came out — that every new or modified building will have to conform to … raise it to higher elevations or other measures.

Now after Sandy it became clear that the old FEMA maps were outdated … In many publications, we have said that this is one of the most fundamental things that has to change. ... It was long overdue.

A little side story to that, four to five years ago I was chairing a session in a meeting of the National Institute of Building Sciences in Washington, D.C., on reducing risks from natural hazards. I spotted the FEMA guy in the room responsible for national flood insurance rate maps. I said, “Would the gentleman from FEMA please tell us when they are including sea level rise in their coastal flood mapping program?” He said, “As soon as Congress mandates it.” Which means never, given our Congressional situation where some still argue about the existence of climate change. Sandy did what Congress didn’t do.

It shows the kind of difficulties when we rely on national initiatives. As long as we can do homegrown initiatives, meaning New York City, New York State, or counties, I think we are much better off in getting things done. States can negotiate with FEMA for local solutions, so Congress doesn’t have to mandate it nationwide.

GG: Do the new flood maps use data based on projected sea level rise from climate change? How did Sandy trump Congress?

KJ: There is nothing stated about sea level rise on those new maps. It’s simply an emergency update based on Sandy data. They don’t have to say anything about sea level rise. Now we have confirmation — here is the new data. Officially, climate change doesn’t enter in. That’s how politics works in this country.

GG: Where is the connection between international negotiations on climate change and local planning here? How does the link ever get made?

KJ: That link is 20 years away. We better act on our own behalf. I am acting on my own behalf in my own house (by raising it). It doesn’t come top down—it goes the other way. The pressure will come from the communities. You see this already in certain areas of Staten Island; I have heard that some have voiced great interest in being bought out by FEMA. That’s the kind of grassroots experience that translates into politics. The new FEMA maps will affect from now on what happens in this area. I’m sure there are some people that won’t like it. It costs money to live up to future FEMA regulations.

GG: Are people aware of the costs that are coming? How is the city of New York approaching this question?

KJ: We haven’t seen the new elevations for NYC. The city is holding back on their wording until that info is either informally available to them or released publicly. It’s a touch-and-go situation, everyone is in limbo, and is scratching their heads as to what to do while all of this rebuilding action is going on. A small thing: I raised my outlets to a higher level in my house. I have my furnace in the attic. These are simple measures that you can do. The city really should insist on doing that everywhere too …

GG: These maps will require that people have to elevate?

KJ: Not necessarily for existing structures … If it’s just normal repairs. They are grandfathered in. Right now, with Sandy repairs, it’s not clear where it falls. I believe it’s at the discretion of the city what they want to insist on.

GG: But some areas will no longer be insurable? That may push some of this?

KJ: That’s exactly the concern. I don’t have flood insurance. I am just as much affected as the Battery is. So is the entire Hudson Valley, all the way to Troy, to the Federal Dam just upstream from Albany. Because it’s all tidal.

GG: You’re still sitting on the New York City Panel on Climate Change?

KJ: We haven’t met since Sandy, but NPCC is an ongoing effort that will survive the mayoral change. It has been adopted into city law. The NPCC is an ongoing institution that will periodically advise the city on climate change issues … There is another body — the Climate Change Task Force — both have been written into the city charter. It’s at the behest of the city when it will call for input, and that has not yet happened since Sandy. Also the International Panel on Climate Change will come out with a new report — the last one was in 2007 — that will provide a new baseline. The NPCC has to look at it and say, “that’s the international consensus. How does that trickle down to us?”

GG: Beyond the FEMA data, are there any other key results from Sandy, particularly at the city and state level?

KJ: That whole discussion about the barriers has taken front seat. The mayor and the governor are not necessarily seeing it in the same way. My impression is that the mayor is much more circumspect and realistic about it … He has advice from the panel and task force. There are serious concerns about the barriers. They are very appealing as a quick fix. It’s a simplistic approach. But life is not that simple.

Many of us advised the Mayor’s Office of Long Term Planning and Sustainability. I’m also a technical advisor to the Department of City Planning. They are going about it in a much more holistic way. Barriers are an option in a portfolio of measures. The advisory panels were established before Sandy and they are continuing with their efforts. Sandy has provided very important data to verify certain notions that already existed from the NPCC and other studies. There were forecasts as to where the water would go and how high. We have seen it can go higher …

The governor jumped on the idea of barriers immediately. Congressman Jerry Nadler wrote a letter three or four months before Sandy to the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning to produce a study of barriers. There were other politically motivated voices pushing in that direction. There is another barrier lobby — Dutch engineering firms. They smell a big job. Ever since Katrina, they have been roaming around the city with the help of the Dutch consulate general. I’m a little bit of a barrier skeptic and a thorn in their skin. [He laughed at this.]

GG: You have said publicly that you don’t see storm barriers as a long-term solution.

KJ: I do not deny that they have a medium term benefit that’s very attractive. Storm surge barriers are very good at keeping out the high water during storms, combined with high tides, because they have a certain height. Assume we have 5, 6, 8, 10 ft sea level rise. You could build barriers against that if you have enough money … Let’s take $30 to 40 billion. Make them high enough, you could keep storms out for 100 years.

That’s very good news … Not only in New York City, the whole Hudson Valley and the MTA, with all its assets that are on the protected side. But not any assets out on Long Island. Just outside the barriers it gets a little worse, during storms, when the barriers are closed, the water piles up on the outside of the barriers. Connecticut will not like it. Long Islanders will not like it. New Jersey outside the barriers will not like it … The communities south of Sandy Hook.

Or, if the big barrier from Sandy Hook to Rockaway is not built … Then it may be three smaller ones near the Verrazano and Whitestone bridges, and across Arthur Kill. Then, the people in the outer harbor might not like it. Because that’s where you get an extra 1 to 2 feet storm surge rise. These are local difficulties. But barring those — that’s not my issue. Also barriers will become a political playball that will delay their building. There will be lawsuits … A West Way dejas vus.

My real concern has to do with long-term sea level rise. The barriers are mostly open — the sea level will get in and out of those barriers. Once sea level rise reaches about 6 to 10 feet … You can’t keep the sea level out (using the barriers) … Because the Hudson brings its water down. You have to get the Hudson water out into the ocean, otherwise the barriers are working the opposite way, they would fill up from behind … It’s not just the Hudson. It’s the Passaic, the Hackensack, the Raritan. All this inland water has to get out into the ocean.

You have two options: Either you open the gates and let the ocean in and equalize, or you have to pump out this river water and keep the ocean out all the time. We would become essentially like New Orleans, which has levies and dikes around it. They are below sea level and rely on huge pumping systems to keep out the water from the higher Mississippi and the ocean. They pump it out all the time. 24-7/365. Those systems have to work all the time. To do such a pumping system for New York — that would produce a lot of greenhouse gases. It’s another reason why this is unsustainable.

GG: What does such a pumping system do to the natural ecosystem?

KJ: We don’t know. We haven’t done any studies. That’s why I think the Mayor is smart. He understands the issues. He realizes that solving all of these problems, and others still coming out for barriers and their environmental impacts that will be unacceptable, will take 10 to 20 years. He wants to do something that’s doable now, and that’s doable on the nickel of the city. Rather than wait for federal money raining down and hoping for the best … and having NYS, NJ, CT and almost 300 jurisdictions agree to a big plan for a delta works …

GG: So you’re saying that the barriers don’t address the core issue?

KJ: The ocean will rise to the point where it will encroach certainly on the neighborhoods out in Breezy Point, Newtown Creek, parts of Manhattan, Jersey City... Current discussions on barriers miss the boat: sea level rise. I don’t know why that’s not under discussion.

That’s what your article has to point out: Folks, you’re missing the big picture. You’re fiddling around on the edges — the scary edges of stormy days… The barriers will be effective only for the scary edges …

But my concern doesn’t become effective until sea level rise reaches 4, 5, 6 feet or more. And it will effect gradually first the lowest-lying areas, and then gradually go up …. That’s where all those regulations — the ABFEs — come in. There’s a lot at stake right now: how the city wants to shortcut the red paper for rebuilding quickly now, while on the other hand look to the future and insist on rebuilding at higher elevations (and other protective measures).

GG: What does the latest data say about sea level rise relative to New York City?

KJ: The NPCC came out with two forecasts. One was based on IPCC data, which essentially had 2 feett of sea level rise by the end of the century. But with a footnote. It leaves out the ice melt in Greenland and West Antarctica. Knowing that shortcoming of IPCC, the NPCC came out with a second model that did the best we could in taking into account historic geological sea level rise rates that have occurred at the end of glaciation times, and took other projections from satellite measurements for this second scenario. That is called Rapid Ice Melt Scenario — RIMS. It has 2 feet of sea level rise by the mid-50s; 4 feet by the mid-80s; and if you project to 2100, it’s essentially 5 feet, plus/minus 1 foot by the end of the century.

If you take the 6 feet from the RIMS, which I personally think is the more likely value, that’s when the barriers become dysfunctional. Once you have 6 feet, you start to inundate a lot of areas, particularly if you have weather on top of that. The new BFEs will have to be updated twice between now and the end of the century to keep up with sea level rise.

GG: Of all the impacts of climate change discussed in the NYS Climate report — severe weather, heat waves, etc. — is sea level rise the core issue?

KJ: Yes. Sea level rise is the ultimate fate of the city. The heavy precipitation, heat waves don’t challenge the existence of the city. Sea level rise gets at the jugular. It truly threatens the livelihood of the city as we have it now — unless it adapts. It can adapt. It can be a totally lively city without barriers. We are lucky. We have high ground within our boundaries. Neither New Orleans nor Amsterdam nor Venice have that luxury. We have that luxury. We just have to move together on higher ground.

Unfortunately, Jane Jacobs may not like it. We may have to modify some of our low-rise neighborhoods and make them higher-rise neighborhoods. At least we have that option. We better do it in the form of a planned, managed retreat, rather than chaotic reactions to the Sandy’s of the future. That’s where urban planning comes in.

That hasn’t sunk in yet, even with the forward looking folks in the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and the Department of City Planning. They still think in decades, instead of a century or longer.

GG: Where is the city in terms of thinking about the rest of the 21st century?

KJ: I’m kicking them left and right. It’s like moving mountains.

GG: Will all Zone A areas eventually have to be evacuated?

KJ: Not wholesale. Many of them will be evacuated and transformed into a nice waterfront, green parks, more than we ever had asked for. There’s a wonderful future to be seen. It’s an incredible opportunity for NYC. Those structures and buildings that we want to keep there — there are several options … The Customs House (in Lower Manhattan) could be lifted up. Or, cheaper, you just give all this basement stuff up. Waterproof it, etc., and take out all the electric control systems from the basement of that building … put them up on the roof, or the 10th floor … that’s a small price to pay.

GG: What about all of the buildings that are owned and operated by the NYC Housing Authority in these areas?

KJ: Let’s take the public housing in Red Hook, which is in bad shape after Sandy. They still have boiler trucks outside … I guess theoretically you could lift them up, but I think it would be cheaper to build new ones if you insist on having structures like them at such locations. It would be much better to find a place within the five boroughs to create new public housing that’s safe. All the houses that were built out on Coney Island and the Rockaways, it’s so unsustainable.

All that stuff that was built north and south of Newtown Creek, the waterfront of the East River … These were all plans that have been in the works for 10 to 20 years. At that time, nobody had any idea that sea level rise and climate change would play into it. Same thing with Willets Point, Hunters Point and all these development projects ... Look at the Westside Yards.

Our institutional inertia is 10 to 20 years out of pace with our climate knowledge. Unless we make changes — that’s in the hands of the mayor. He can whip those plans into shape. He’s treading too slowly on incorporating those changes, I think.

GG: Where is the mayor’s inertia coming from? Is it intellectual? Is it pressure from the real estate industry?

KJ: It’s everything. They all work in the wrong direction. We are all in risk denial. I am sometimes in risk denial. It starts with the individual, then come the institutions, and then come short-term interests like the real estate industry … Developers hold onto risk only for the time it’s in development, and then they sell it to whoever buys it. The risk is transferred to the new owner … There’s no law that tells the developer to tell the new owner what the risk is, or — more consequential — (that he or she is) liable for it.

GG: You have stated that the thrust of PlaNYC was not to prepare for climate change, but, rather, to plan for a projected one million new residents by 2030.

KJ: Everything else was an afterthought, which was pushed by the scientific community … (Climate change) was patched on to it. It wasn’t the original motivation for it … The updated plaNYC that came out three years later faced climate change much more upfront, but still only in a short term way. If you read the language, you see it was not written by scientists. Why should it be? For instance, there are sentences in there that say we have a fixed amount of land and we have to make better use of the land. We don’t have a fixed amount of land. It’s being reduced (by sea level rise). That wording is wrong. The thought is wrong. Intellectually it hasn’t sunk in.

GG: Are you saying that the operating premise for PlaNYC has to be different? For instance, how do we plan for a potential 6 foot sea level rise at the end of the century?

KJ: And it doesn’t stop at 6 feet at the end of the century. It will accelerate for at least 200 years. Maybe in 500 years, it will start to level off if we get a Kyoto-like protocol. Which we still don’t have. So this city will have to live with an ever smaller footprint. And we can tell roughly where it’s going.

Maybe future generations will come up with some smart way of carbon sequestration … But it won’t affect sea level rise for another 500 years … Because we have front-loaded so much CO2 into the atmosphere … By all likelihood, we are locked into sea level rise for a long time.

The density patterns of the city will have to be changed. We will have to move together on the high ground we have, and hand the filled-in lands at the edge of the city back to the sea. Yes, we are a waterfront city — but with the luxury of high ground. There will be losers. There will be winners.

___

Photo of Sandy from NASA.

After Hurricane, Some Begin To Question Wisdom of Rockaway Pipeline Project

NEW YORK — Now that the construction of a new chain of natural gas pipelines running from the Rockaway peninsula to Brooklyn has been delayed following Superstorm Sandy, residents and elected officials are beginning to question whether the project is safe to build at all.

The exceedingly complex project would be constructed in separate phases — under the regulation of federal, state and local authorities — adjacent to coastal communities that were among the hardest hit during the storm.

U.S. Rep. Yvette Clarke, who represents central Brooklyn, told Gotham Gazette in an emailed statement that the destruction caused by Sandy had raised concerns among residents who live near the proposed gas pipeline project.

"Our need for independent energy cannot precede the safety of our community and environment," she said.

State Sen. Joseph Addabbo, whose new district includes the Rockaways, said he would organize a town hall meeting where residents could ask their questions about the project.

"Doing this simultaneously with Sandy becomes a daunting task," he said of the project. "People are trying to get their lives back."

He added that residents have come to him with some hard questions about the project. “This is a major endeavor," he continued. "What is the protection from a gas leak? What are the precautions? What is the time frame?”

National Grid spokeswoman Karen Young told Gotham Gazette that the storm had not affected phase one of the project — the utility’s plans to construct two gas pipelines underneath Jamaica Bay’s Rockaway Inlet. She added that they were "still meeting with all of the officials and agencies to determine the best time.”

Oklahoma-based Williams Companies, which is also constructing sections of the pipeline, was still expected to move ahead with its part of the project.

Williams spokesman Chris Stockton said on Friday: “The hurricane has not changed our plans, nor has it changed the need for this project and the gas for the city." But, referring to the fact that Williams’ portion of the project had not yet received the necessary approvals, he added that there was "still a long way to go.”

Asked whether additional precautions needed to be taken during pipeline construction, Young said: “We had a robust plan in place, and the measures that we are planning to implement are above and beyond industry standards”.

She added that the pipeline had been designed to withstand flooding, would be buried underneath the seabed of Jamaica Bay and regularly monitored and inspected, especially during severe weather events.

Young stated that National Grid felt it had designed a "very safe” pipeline. She noted that the pipeline would have isolation valves that could be activated remotely in the event of an emergency.

The Rockaway pipeline is a key part of the energy initiatives outlined in PlaNYC, Mayor Bloomberg’s far-reaching sustainability plan.

The mayor’s office did not respond to questions regarding whether construction or ongoing maintenance of the Rockaway pipeline would need to be re-thought in light of the area’s vulnerability to future catastrophic storms.

SANDY'S ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

A full month after Sandy made landfall, the profound impact of the storm on both the residents and natural environment of the Rockaways is grimly evident.

Major arteries in the Rockaways were jammed with emergency and utility trucks on Saturday, and construction on damaged homes was visible throughout. In Breezy Point, the community closest to where pipeline construction will begin shortly, it was possible to see homes that had been torn off their foundations, and a car that had been incinerated almost beyond recognition by the fires that engulfed the area.

Much of the construction on the pipeline will take place in Gateway National Recreation Area, a 26,000-acre National Park, which includes ocean-facing Jacob Riis Park and the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. The Bay’s wildlife refuge is the only such refuge in the National Park System, according to the New York Harbor Conservancy.

Other sections of the park — which will eventually be adjacent to pipeline construction — are now serving as sites for hurricane clean-up and reconstruction efforts.

“The Bay has taken a big hit,” said Dan Mundy, vice-president of Jamaica Bay Eco-Watchers. He added that “tremendous amounts” of fuel oil and debris had entered Jamaica Bay as a result of the storm, and that two freshwater ponds had breached “in a very dramatic fashion." Mundy explained that tides had flushed out much of the oil, but he added that the post-storm period was a “critical time for mitigation”.

Just across the Bay, the scope of the tragedy of the storm is visible in the parking lots of Jacob Riis Park, which have been turned into a massive dumping ground for the remains of destroyed homes and other refuse. From the dumping ground, one can see the fences and other beach infrastructure torn apart by the reported 14-foot coastal storm surge that entered the area on the night of Oct. 29.

Because of its vulnerable position, areas around the Rockaway peninsula are now considered possible locations for storm barriers.

A key section of the Rockaway pipeline, to be constructed by Williams, will run directly underneath Jacob Riis Park, delivering gas from an off-shore pipeline to National Grid’s new mains underneath Jamaica Bay. The 10,000-mile Transco natural gas pipeline, which runs parallel to the Rockaway coast, is managed by Williams.

In a later phase of construction, National Grid will connect its cross-Bay lines to customers in Brooklyn and Queens, via a new gas meter and regulating station to be housed within a historic hangar at Floyd Bennett Field, and by eventually linking with an existing gas main on Flatbush Avenue.

The 60,000-square-foot meter station will be constructed by Williams. Parking lots behind the hangars at Floyd Bennett Field are currently a massive staging area for FEMA, the Red Cross, construction companies and scores of fuel tanker trucks.

The National Grid portion of the Rockaway pipeline project has been approved by the city and did not require a public review process or full-scale environmental review. Williams’ off-shore pipeline and meter station proposal, however, is still working its way through a federal environmental review process.

Chris Stockton said that Williams planned to submit a final proposal to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission by late 2012 or early 2013. He said that based on the company’s experience with previous applications to FERC, the agency’s review of the proposal could take another eight months.

President Obama signed legislation Nov. 27 bringing the Rockaway pipeline project one step closer to reality. The New York City Natural Gas Enhancement Act authorizes the National Park Service to permit the pipeline and related infrastructure within the boundaries of Gateway National Recreation Area.

In a statement on the signing, Mayor Bloomberg said: “Given the destruction of Hurricane Sandy, this law could not come at a more critical time for New York City. This pipeline will help us build a stable, clean-energy future for New Yorkers and will ensure the reliability of the City’s future energy needs.” The mayor specifically thanked the bill’s sponsors, Sen. Charles Schumer and Congressmen Michael Grimm of Brooklyn and Staten Island, and Gregory Meeks of Queens.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

The Rockaway pipeline project has spurred protests from some local residents and environmental groups, who have raised questions about possible impacts to coastal marine life, and whether a gas pipeline is an appropriate use for an urban park. The city’s commitment to natural gas — a fossil fuel — as an ongoing energy source has also proved controversial.

“This bill puts a pipeline under a popular beach and introduces private industrial use of a federal park, and it does so with no public input,” said Karen Orlando, a local resident and Floyd Bennett Garden Association member.

Local groups like Jamaica Bay Eco-Watchers are watching the federal review process closely, and believe that they may be able to impact decisions that are yet to be made. They also say that the Rockaway Pipeline speaks to public policy questions relevant to the entire city.

Mundy argued that if the Williams section of the pipeline project is to go forward, there must be a commitment to off-set some of the ecological damage that he said he believes will inevitably be inflicted by construction of a 2.79-mile pipeline on the ocean floor.

Another federal agency has raised questions similar to Mundy’s. In October, the Army Corps of Engineers wrote to FERC, requesting that Williams provide more specifics on the ocean floor trenching and dredging techniques it will use, and how the aquatic ecosystem off the Rockaways could be affected.

Stockton said that questions on the project raised by the Army Corps and other agencies would be addressed in the company’s final proposal to FERC.

Mundy said he believes that any possible damage to the ocean floor habitat should be offset by a focus on restoring Jamaica Bay’s saltwater marshes.

Marshes throughout the city have attracted new attention because they can help to blunt the impact of coastal storm surges. “The wetlands will be a big topic of discussion,” said Mundy. He added that not only are they a form of “soft infrastructure”, but they also help to absorb carbon from the atmosphere.

At the same time, Orlando argued that the placement of what she describes as “industrial infrastructure” within Floyd Bennett Field, “a couple hundred of feet from a community garden used by four to five-hundred members and their families” has broader implications for both private use of public space and government transparency.

She said the city "couldn’t do that in Prospect Park or Central Park.”

___

Photo of temporary dump at Jacob Riis Park courtesy of the New York City Department of Sanitation. Photo credit: Michael Anton.

Little Known Stormwater Reporting Could Be Nixed

NEW YORK — A proposal to eliminate the reporting requirement of the city's plan to sustainably manage the discharge of billions of gallons of stormwater that can contaminate rivers, bays and other water bodies is being criticized as a potential blow to accountability.

A city commission is expected to vote today on whether to eliminate more than a dozen reports and advisory committees that are no longer considered useful, including the little-known reporting requirement of the stormwater management plan.

A city commission is expected to vote today on whether to eliminate more than a dozen reports and advisory committees that are no longer considered useful, including the little-known reporting requirement of the stormwater management plan.

Environmental groups say they are perplexed by the push to eliminate the reporting requirement of the stormwater management plan, especially in light of the strong possibility of more severe storms like Hurricane Sandy that can cause overflows.

"If we have that problem already, and we have potential storm surges and flooding, the concern is that they can overwhelm the storm sewage system," said Phillip Musegaas, program Director at Hudson Riverkeeper.

He said that if the reporting requirement is eliminated, there will be "no overarching process" that looks at stormwater management city-wide.

Between one-half to two-thirds of the city relies on an overflow sewer system comprised of two sets of linked pipes. One set of pipes moves raw sewage toward treatment plants, while the other drains rainwater from the streets toward the city’s waterways. In the event of sustained rainfall, rainwater from the streets eventually backs into the sewage pipes and the city must release both raw sewage and storm water into local waterways.

Stormwater is considered a possible public health hazard, with untreated discharge potentially carrying bacteria and other pollutants into the city's waterways. Developing a more sustainable stormwater system is seen as critical to advancing water quality.

Green infrastructure solutions — such as the restoration of wetlands and the use of water permeable pavement — tracked by the reporting requirement could assist in mitigating the impact of storm-related flooding and storm surges, the groups argue.

They also say eliminating the reporting requirement will remove public accountability for stormwater management planning in outlying sections of the city such as the Rockaways, Northern Staten Island, South Brooklyn, and large sections of Queens are left out of current reporting.

“Why is this happening? The city is saving tens of millions of dollars on the green infrastructure plan," said Rob Crauderueff, coordinator of the Stormwater Infrastructure Matters coalition. "Would it not make sense to continue reporting — to encourage creative thinking?"

He added, "Reporting is a way to make sure that there is a continued relationship between the policies that the city puts out and the public.”

Councilman James Gennaro, D-Queens, the chair of the committee on environmental protection who sponsored the legislation creating the stormwater management plan, said Friday a deal had been reached with the mayor's office to retain the requirements for the storm water management plan within other reports generated by the city.

“I don’t have a problem with the Bloomberg administration cutting back — but we have to be careful," he said.

Details of the deal weren't made public ahead of the commission's meeting.

The mayor's office, which supports eliminating the reporting requirement, seemed to confirm Gennaro's claim.

A spokeswoman for Bloomberg's office, Lauren Passalacqua, said the stormwater management initiatives would instead be reported in the annual progress report of the city's sustainability blueprint, known as PlaNYC.

The commission will also weigh whether to eliminate some clearly outdated or unusual boards and reports, such as a committee to advise the Health Department on tattoo-related health issues and a report on horse-drawn cab stands.

Also flagged as unnecessary by the commission are a biannual report on class size, an annual report on housing needs and a commission on foster care of children.

Any vote by the commission to eliminate the reporting requirement for the stormwater management plan will require City Council approval.

Hurricane Sandy And Red Hook