|

"A tremendous number of schools aren't making the grade," Peter Kerr, a spokesperson for Klein told the New York Times. "We're talking about hundreds of schools and thousands of families that are dealing with failure."

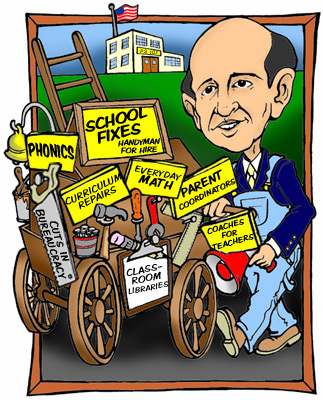

In an effort to address that, Klein and his team have spent the last 10 months completely overhauling the school system. Under their "Children First" initiative, they have changed the Department of Education's administrative structure, virtually eliminating the 32 community school districts and replacing them with 10 instructional divisions. Entire offices at the Department of Education were shut down in an effort to do away with excess bureaucracy. The mish-mash of disparate curricula that existed has been tossed out in favor of a uniform new curriculum for math and literacy.

Some see the full-speed-ahead approach as the only way to bring reform to an enormous, bureaucratic and complex system. Others say that there has been too much change too quickly, creating disorganization and confusion. Some see the reforms themselves as innovative and ambitious. Others find them untested, poorly designed and just plain wrong.

Revamping The Bureaucracy

The Department of Education recently held a "Parent Academy," a week-long training session for the city's 1,200 new "parent coordinators," one for every school, hired over the summer to boost parent involvement. Many of the new parent coordinators arrived for their training bright-eyed and energized. "What do I do with the courage and excitement I'm feeling right now?" one man said.

But the new coordinators also had plenty of unanswered questions. "It seems that there is a lack of understanding about my position and what it entitles me to do," noted one, echoing the concern of many of her colleagues. Some parent coordinators remained unsure what their budget was, or whether they even had one.

Their confusion is typical. The overhaul has created thousands of new positions even as others were eliminated. The 32 community school districts still technically exist, largely to comply with state law, but their offices have been whittled down from a few dozen administrators to just three employees

The 10 "instructional divisions" each consist of between two and four of the old districts. Until now, parents went to their district office when they had questions that could not be answered at the school level. Now, they go to "learning support centers" -- new offices in the instructional divisions.

But staff at the learning support centers may not have answers to pressing questions about registration, transfers, after-school programs and other key subjects. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum released a survey that found learning support center workers could not answer common questions. The report found, for example, that in a telephone survey of all ten support centers, none could answer questions about the documentation required to register a child.

Klein has conceded that many people in the system are learning on the job. "The fact that you don't get an answer immediately is not a major issue," said Klein. "The fact that you get an answer is critical."

Rosalyn Inman, a parent coordinator from Brooklyn, echoed Klein's sentiments. "Most of what we are going to need to know," she said, "we will learn as we go."

Advocates anticipate that, over time, the kinks will work themselves out. "Change is painful," notes Noreen Connell, executive director of the Educational Priorities Panel. "Might as well get as much as possible done in one, miserable year."

The New Curriculum

The real work of the school system, of course, goes on in the classroom. The standardized curriculum for all but about 200 of the city's so-called "high-performing schools" addresses that.

Until this year, districts and even individual schools selected their own curriculum. The lack of a standard approach posed particular problems for students who frequently transferred. With no clear guide, schools often switched from one curriculum to another, confusing students

Whatever the merits of the programs selected, some advocates say that Klein has taken a huge step forward by standardizing the programs for teaching literacy and math. "Every school was 'reinventing the wheel,' and some failing schools were reinventing the wheel every two years and doing it very poorly," said Noreen Connell. "Now consistency and depth in delivering instruction is a real possibility for most schools."

In literacy - reading and writing - the curriculum teaches children to read by having them read books that interest them. Under this approach, called "balanced literacy," Dick and Jane are out, replaced by classroom libraries where students can select books at their particular reading level.

The math program emphasizes problem solving over memorization and focuses on the way math is used in real life. Students use "manipulatives" such as blocks, rods and games to learn math concepts. For example, rather than being presented with a sheet of problems to learn addition, first graders might play a game with dice.

The new curriculum relies on what are generally viewed as progressive ideas about teaching. The math program, called "Everyday Math," emphasizes "understanding concepts rather than mastery of basic operations," and balanced literacy "focus[es] more on children working among themselves than on direct instruction," James Traub wrote in the New York Times.

Many experts have criticized the choice of the programs, charging that they do not give enough weight to traditional teaching methods. Using such programs in New York City schools could be "a disaster in the making," Sol Stern wrote in City Journal, "not least because the children in the targeted schools are mainly poor and minority - the very population historically most damaged by such methods."

Writing in the New York Sun, Bas Braams of the NYU mathematics department, faulted "Everyday Math" for offering a confusing array of methods for basic arithmetic, jumping around from topic to topic, and for introducing calculators in kindergarten.

More debate swirled around phonics, which teaches kids to read by emphasizing the relationship between letters and their sounds. Conservatives, including many in the Bush Education Department, favor this approach. But rather than endorsing a full-fledged phonics program, Klein and his educational expert, Diana Lam, decided to give students in lower grades a half hour of phonics instruction a day in addition to their other reading and writing work. Critics promptly charged that the program they selected -- "Month by Month Phonics" -- was untested, and, in fact, not focused on traditional phonics methods at all. In the wake of such criticism and threats from the Bush administration not to provide funds for the program, the school system selected a more traditional phonics program to supplement "Month by Month Phonics."

Klein has pointed out that the curriculum he and Lam chose is already being used in some successful city schools. Some of the city's highest performing districts, such as district 26 in Northeastern Queens, use balanced literacy. In March, the New York Times profiled P.S. 172 in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, a school that was already using both "Everyday Math" and balanced literacy, as well as phonics. The school has good test scores, despite a disadvantaged student body.

In discussing the math curriculum, school principal Jack Spatola said, "The beauty of the program is that it individualizes teaching and learning. That helps kids to understand a process rather than just regurgitating it."

Teacher Training

Beyond the substance of the new curriculum, many principals and experts have expressed doubts about how teachers were trained.

Over the summer, teachers received a compact disc that provided an overview of the new curriculum. And this year school started a few days later than usual to give teachers four days of training about the new programs. To help teachers as they go along, the Department of Education has hired math and literacy coaches for each school using the new programs.

Stephen Porter, the principal of PS/IS 226 in Bensonhurst, thinks the uniform curriculum will improve continuity as students move from grade to grade. But he does not think teachers had enough time to become accustomed to the new programs before putting them into use. While the quality of training was good, teachers need more time to absorb it, he said. "You want [teachers] to really think about it," Porter said. "Right now, it is difficult for them to think, they are working so hard just to keep abreast of what is going on. They are trying to keep a day ahead of the kids."

But Robert Klein, a local instructional supervisor in Queens' Region 4, says that the new programs have gotten off to "a smooth start... Teachers have organized rooms and are using the new strategies."

While the new curriculum went into effect very quickly, it will take far longer to see the effect of the reform. "Instructional change is hard," said William Stroud, the principal of the Baccalaureate School for Global Education in Astoria who worked on the new curriculum. "People are looking for a quick fix to the achievement problem. If our expectation is that we are going to see results in one year or two years, we are going to be disappointed. We should expect to see improved student achievement in three to five years."

Given the magnitude of the changes, what was most striking on the first day of school was how much remained the same. Students, many toting new backpacks laden with supplies, struggled to find their classrooms and loudly called out to their friends. Teachers welcomed students as principals tried to deal with the customary confusion of making sure children ended up where they were supposed to. Asked if this year seems different from last, a tenth grader at the Baccalaureate School shrugged her shoulders and offered, "I have a new math teacher."

But the city still has a huge student body with many needs, and a lack of resources. The perennial problem of overcrowding may be even worse than usual this year, prompting the United Federation of Teachers to file grievances charging the classes are so big they violate the teachers' contract. And so, the real test of Children First will be to see whether it can improve performance despite these immense challenges.

Deborah Apsel is a reporter with Inside Schools, a web site published by Advocates for Children.

Related Article

Put Class Size on the Ballot

The New York City public school system is undergoing major changes. But little progress has been made, writes Leonie Haimson, to fix the system’s most serious problem: large classes.