After Escaping Domestic Abuse, Survivors Confront the Housing Crisis

Emergency response to domestic violence survivors and their children has, over the past two decades, come a long way. Those who work in the field can point to a partnership of shelters and advocacy organizations, government offices, legal experts and police precincts that now provide assistance to protect women and their children from dangerous and abusive partners.

Despite these significant advances, the city still has not come close to meeting the need for shelter beds and for transitional and permanent housing. This forces many survivors to choose among street homelessness, the revolving doors of the city's homeless shelter system or returning, with their children, to their violent abuser.

Even with a 35 percent increase in emergency shelter beds for survivors and children over the past year, emergency shelters report they turn away hundreds of callers away everyday. Many of those they do shelter fail to secure follow-up transitional and permanent housing.

The Epidemic of Abuse

Advocates say one in four women experience a domestic violence incident. The New York City Domestic Violence Hotline answered more than 134,000 calls in 2008, an average of 370 calls per day. (The hotline, which provides help in many languages, operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and can be accessed by calling 911, 311 or 1-800-621 HOPE.)

City police responded to more than 234,000 domestic violence incidents in 2008 -- an average of more than 600 incidents per day.

The Role of Law Enforcement

This level of police involvement represents a huge change in just a few decades. Thirty years ago, police often did not respond to domestic violence complaints. Many thought such violence was a private family matter and that a woman was her husband's property. Officers essentially blamed the victim.

Now, the New York City police respond and "respond skillfully", said Maureen Curtis, associate vice president of Bronx Criminal Justice and Community Programs for Safe Horizon, one of the largest providers of services to survivors of domestic violence in the country. Advocates credit some of this to the state's Mandatory Arrest Law, enacted in 1984, which requires police to arrest the abuser under certain conditions.

Training in domestic violence intervention has also improved. Safe Horizon advocates can be found in 13 of the city's 84 police precincts, concentrating on those with the highest crime rates. High crime districts are also the districts with the most reported domestic violence incidents, according to Curtis.

Getting Help

Most survivors have called the police and the domestic violence hotline many times before they try to break free from their abusive partner and seek emergency shelter.

Once they make that decision, though, there is no guarantee they will find the shelter they need, according to Sanctuary for Families, the largest nonprofit agency in New York aiding victims of domestic violence and their children. But only "several hundred" get emergency shelter.

While many victims can stay with friends or relatives, hundreds of women seeking shelter are turned away from Sanctuary every day for lack of available beds, said Shugrue dos Santos, deputy clinical director of Economic Empowerment Programs for Sanctuary for Families. "All our services are overextended and we are asking the city for more shelter beds," Shugrue dos Santos said.

The Human Resources Administration administers some 50 emergency shelters for 700 families with approximately 2,500 emergency shelter beds citywide. The maximum stay for emergency shelter is 135 days.

As soon as the victim enters the emergency shelter, counselors try to determine her safety risk. The survivor and her children will be assessed for trauma by a psychiatrist and a psychologist.

"The children need crisis intervention services not only because of the devastating impact of watching their father beat their mother but because in 60 percent of the cases we get, the father is also battering the kids," Shugrue dos Santos said. She added that survivors arriving at the shelter are suffering from post traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression or bi-polar illness, and often have medical problems like asthma and high blood pressure that are exacerbated by the stresses of abuse.

"Sanctuary's roots are feminist, rooted in the belief that gender oppression and inequality is at the root of domestic violence. Violence occurs when one person uses their power to control another person," Shugrue dos Santos said.

Not all victims of domestic violence are women and not all perpetrators are men. Also, men are abused in both heterosexual and gay relationships. However, statistics indicate that these forms of domestic violence are much less frequent than men abusing their female partner.

"Shelter is a last resort, a place to hide. It's reserved for families in acute safety risk, and only after all other options fail. …These women come with their kids and a garbage bag of clothes,” Shugrue dos Santos said. "They have tried to get away from the abuser many times before. It's a choice between … a full refrigerator and hunger. Many survivors choose the full refrigerator for their kids over their own personal physical safety."

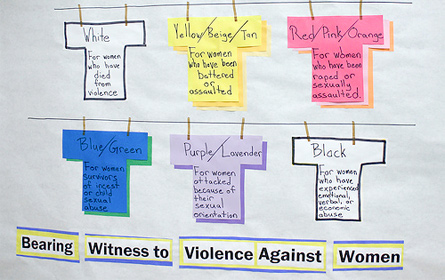

Different Women, Different Needs

Not every victim of violence falls under the stereotype of a badly bruised victim "fleeing in the middle of the night," said says Barbara Brancaccio, spokesperson for the city Human Resources Administration. "Every client comes in at a different place in her life, with her own set of options, her own individual needs, her own unique scenario. Some can find a job on her own, while others need employment training and placement. In some cases, the woman must get public assistance, but others have money and income of their own."

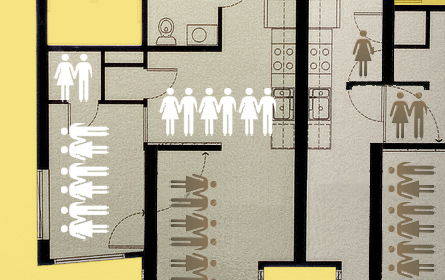

The New York City Family Justice Center, a partnership of government and nonprofit domestic violence agencies all under one roof, is an example of the evolution in domestic violence services. While the centers -- one in Brooklyn and one in the Bronx -- doesn't offer anyone a bed, it is a multi-faceted, all in one stop, emergency intervention, needs assessment and resolution center. In one visit, the victim can get help finding emergency shelter, documenting and filing a police report, and applying for public assistance. She can be examined by a forensic medical practitioner, get legal help, meet with advocates from non-profit agencies, and, if she wants it, get spiritual counseling. Help comes in 150 languages.

According to the mayor's Office to Combat Domestic Violence, 96 percent of victims who used the services of the Family Justice Center did not report subsequent harm from their abusers. And there was a 36 percent decline in domestic violence homicides in 2007, which the office credits to the work of the Family Justice Center.

After the Shelter

Following their time in emergency shelter, survivors need permanent housing. The Human Resources Administration tries to find transitional homes for shelter clients who need a place to stay for an extended period while they wait for permanent housing or other services to come through.

According to Shugrue dos Santos, approximately 20 to 25 percent of Sanctuary emergency shelter clients move directly into permanent housing. Of those who need to go into transitional housing first, about 50 to 60 percent then find permanent homes.

Some survivors choose homelessness over returning to a dangerous home. "These women don’t have the option of moving out of state to stay with a friend or relative. They’ve already tried that and their husband has tracked them down, putting their extended family members at risk as well," Shugrue dos Santos said.

Women coming out of shelters confront the general scarcity of affordable housing in New York City. “While domestic violence cuts across all socio-economic lines, race, and ethnicity, 98 percent of our clients are, at or below, poverty level,” says Shugrue dos Santos. About 70 percent of Sanctuary clients are immigrants and about 30 percent are not legally documented, making it difficult to secure work or get public assistance.

The women Sanctuary serves, Shugrue dos Santos said, "are not poor as a consequence of domestic violence. Generally, they have always been poor."

Sanctuary's "My Door" after-shelter program helps women who are unemployed, or underpaid, to find jobs. However, clients need recovery time before they can take steps to start working. "They are women, people of color. They are facing classism, anti-immigrationism. …They suffer self-esteem problems: No one ever asked these women what they wanted to do when they grew up, what they were good at,” Shugrue dos Santos said.Approximately 46 percent of the survivors who complete the My Door program are currently employed, Shugrue dos Santos says.

Despite the advances, advocates say that society still needs to confront the magnitude of domestic violence. "Domestic violence is not a private family matter. It is a global human rights violation," said Marcia Pappas, president of the National Organization for Women -New York State.

According to state law, domestic violence is a "family offense," but Pappas believes it should be treated as a "hate crime." “Misogynism, sexism is no different from other isms, like racism and anti-Semitism. It is ingrained in society."

Society still does not take it seriously enough, Pappas said. She said she had recently read in the Albany Times Union, about a man that was sentenced to three and a half to seven and a half years in prison for stabbing a horse. That's more time than men get who do the same thing to their wives."

Illegally Divided Homes Pose Dangers but Fill a Need

Three people were killed and four were injured in a firethat started in the basement of an illegally subdivided house in Queens early on the morning of Nov. 7. The basement reportedly had been split into four bedrooms and the second floor divided into two apartments.

The changes almost certainly contributed to the deadlines of the blaze, An obstructed basement door kept firefighters from reaching the victims, forcing them to cut through bars on the window The crowding made escape difficult for those caught inside, and to make matters worse, the smoke detectors did not work.

The accidents once again focused attention on thousands of illegal -- and dangerous -- homes in the city. While some people simply want to see such houses padlocked, other say that that would leave many poor New Yorkers, newly arrived immigrants and students with no place to live in this high-rent city.

"The argument that these accessory dwellings should not be fined because they provide affordable housing for a lot of people is a wonderful argument before the fire. After the fire the city is blamed for it," said Dan Andrew, press spokesman for Queens Borough President Helen Marshal. "The goal is not to put people out in the snow. We want to put these people in safer, better housing."

The question confronting city policymakers is how to do that.

Cramped Quarters

Illegal units have been around since the 1940s when owners opened their doors to returning World War II veterans. But the homes first got negative public attention in the 1990s after a series of fires occurred in Queens.

Today, most of the illegal residences are one and two family homes whose owners have reconstructed cellars and basements to rent out. Cellars, which have more than half of their height below curb level, cannot be legal apartments under city regulations. Owners also carve out illegal single-room occupancy residences by partitioning bedrooms on upper floors.

This "housing underground," as Chhaya Community Development Corp., a nonprofit housing advocacy and economic development and justice organization, calls it, has mushroomed in predominantly middle-class residential neighborhoods of Queens. These neighborhoods attract immigrants seeking a new start. Many feel fairly comfortable because they already house people from their home countries.

Property owners created more than 114,000 illegal so-called "accessory dwellings" between 1990 and 2000, accounting for about 50 percent of apartments produced in the city during that period. In Queens roughly 48,000 illegal units were built, representing 73 percent of all housing constructed in the borough during that decade, according to the Pratt Center for Community Development, a university based advocacy, planning, the actual number of such residences is almost certainly higher.

While the divided houses often violate fire and other safety ordinances and zoning regulations, they offer many New Yorkers their only source of affordable housing. The city has an apartment vacancy rate of less than 3 percent, according to the latest Housing and Vacancy Survey. Under state law, anything below 5 per cent constitutes a housing emergency.

In addition to recent immigrants, the divided buildings house college students and provide a lifeline for low-income people as well as New Yorkers hard-hit by the recession.

The foreclosure crisis has spurred more of these divided homes. The illegal apartments provide steady rental income to homeowners who cannot otherwise meet their mortgage payments.

A Strain on Communities

But while the divided dwellings fill a need, the units clearly pose serious dangers, most notably to the people who live in them. Many basements and cellars have only one exit, limiting means of escape in an emergency. Exposed and overloaded electrical wiring create an increased risk of fire, as do the portable accessory heaters and hot plates that many tenants use.

Neighbors express irritation about the population explosion on their streets. Complaints to the city's Department of Buildings, its 311 non-emergency hotline and community boards have phones ringing off the hook. These "overstuffed units," to use Chhaya's term, have put a strain and drain on city resources and services, community spokespeople say. In some neighborhoods they contribute to overcrowding at schools and hospitals.

"The result is that a lot of people who grew up here are moving to Long Island, or upstate, or out of state. They say, 'That's it. I'm done. I've had it. It's not worth it. I'm leaving,'" said Wendy Bowne, president of the Richmond Hill Block Association.

In Fresh Meadows and Jamaica Estates, the issue is college students, who rent out upper floor of houses from absentee landlords, according to Marie Adam-Ovide, district manager of http://www.queenscb8.org/ Community Board 8. "We have a weekend, 11 p.m. to 2 a.m. problem," she said. That's when college students' parties spill over into the front yard. ? We have an underage drinking problem," Adam-Ovide said.

In Community Board 10, "about 40 per cent" of complaints are about illegal conversions, estimates chairperson Elizabeth Braton. "Most are cellars," she said. "Cellars are never legal."

The City's Approach

Following the deadly fire in Queens, the city stepped up its efforts to educate people about the dangers of illegal conversions. The buildings department and the fire department have been distributing tens of thousands of leaflets in a number of languages warning people that such homes can turn into deathtraps in the event of a fire.

Building Department inspectors are the front line in the city's fight against illegal conversions. When the city receives a complaint, sends the inspectors to check out the situation. But politicians and community and housing groups say the complaint-based system is punitive, inefficient and lacks sufficient enforcement mechanisms.

The inspectors, however, often cannot get access to the property. According to an audit of the Queens division of the Department of Buildings by New York City Comptroller William Thompson, Jr., inspectors with Queens Quality of Life Unit responded to 8,345 complaints of illegal conversions in fiscal year 2008. They could not gain access on the first time around to 3,279, or 39 percent of the locations.

If inspectors do not get access the first time, they return. Then, if they still are not admitted, they can either drop the case or issue a warrant. Thompson found warrants were issued to less than 1 percent of the illegally converted properties. Throughout all five boroughs, the city has obtained 107 warrants - only about 13 a year -- since 2002, the Daily News has reported.

The Mayor's Management Report, however, paints a somewhat different picture. It said that during fiscal year 2009, the buildings department received 23,326 complaints about illegal conversions of residential space. Inspectors managed to gain access to 49 percent of those locations and "issued violations to property owners in 16 percent of these cases."

In the case of the Queens fire, the city sent investigators to the building in response to complaints in 1990 and 2004. Both times, the inspectors found no violations, Tony Sclafani, a building department spokesman told the New York Times.

Units that are inspected and found to be illegal receive a notice of violation. If the owners do not make the necessary repairs, they are fined and fined again. The fines for repeated violations can reach $15,000. But the fines are rarely paid.

If the inspector deems there is imminent danger to the occupants, a vacate order is filed. According to Thompson?s audit, the buildings department did not follow up on 657 vacate orders in Queens that were issued in fiscal year 2008.

Sclafani has said the city evacuated 1,086 illegally converted apartments in 2008. After the Nov. 7 fire, the Times reported, inspectors found eight rooms next door and evacuated all of them.

Closed Doors

Thompson and Queens Borough President Helen Marshall say the city needs more inspectors. But more inspectors do not mean more access.

"Without a permit they can?t do much," said Bownes. She said that when Rudolph Giuliani was mayor, people from the fire and police departments accompanied the inspectors. Now, she says the homeowners "laugh in the face of the Department of Buildings."

"Maybe if the Department of Buildings were able to enforce the law, word would get out and people would not buy over their means, would not resort to making illegal apartments," Bowne says.

"When the inspector comes, the kids just don't open the door," Adam Ovide said. She said she has seen only one successfully conducted inspection in her two and a half years working for the community board. That building, she said, "was just terribly dirty and unkempt. The yard was full of weeds."

But Mary Ann Carrey said the situation has "improved greatly" over the more than 20 years she has been district manager of Community Board 9.

She said that, in an average month, she gets seven or eight complaints. Her staff goes with the inspectors who usually get access to the building. Still, she said, "enforcing the system is a problem. ? Complaints are so low priority that the courts seldom hear the case."

Even if the hazardous condition in the home can be removed, the problem has not been solved, Carrey said. "If you have three families living in a zone for one or two families in a home, then you?ve got a problem. You cannot just change the zoning code. So what do you do then? I remember Koch saying back when he was mayor, 'What do we do after we evict them? Where are we going to put these people?'"

Looking for Answers.

That is the issue Chhaya hopes to confront. The current complaint system "is not working," said Seema Agnani, the group's managing director of Chhaya. "Penalizing owners has little impact on the housing ground. ? Moreover the complaint system pits neighbor against neighbor, causes discord and distrust."

Chhaya, whose name means shelter, focuses on improving housing opportunities in New York for South Asians and other immigrants. In a survey of homes in Jackson Heights and Briarwood/Jamaica, Chhaya estimates that about a third had an "accessory unit" that could be "potentially legalized."

To accomplish this, Chhaya envisions a pilot program to create a new category of residence, the "Accessory Dwelling Unit" in the city's building code. A panel of expert architects, engineers and planners could determine how these rooms and apartment could meet fire, safety and health rules. Education program in several different languages, offered through private and nonprofit partnerships, would teach homeowners and new homebuyers the city's ordinances and rental laws.

Owners who voluntarily comply with the process and fix their residences to comply with standards for the new accessory units would receive financial assistance from the city and be given a grace period of 12 to 18 months, during which time they would not be fined. "Currently, owners do not have enough of an incentive. "It can take $10,000 to $15,000 to legalize the dwelling. It can take a year," Agnani said.

After the completion of the reconstruction, the owner would receive a certificate of residential status.

In addition, be a community task force would access the impact of increased population density on neighborhoods. "Public resources are allocated based on population. If you bring these units into regulation, if you account for them, the city can allocate more resources for sanitation, can better accommodate overcrowded schools," Agnani says.

Bowne says she refers renters and owners to Chhaya. "They educate people who do not know the law," she said. But, she has doubts about whether the group's proposal will address her community's concerns.

Bottom line, she said, "The illegal conversions are exhausting our city services."

New Efforts Fail to Reduce Homelessness

As Mayor Michael Bloomberg approached the end of his first term in 2004 with his eye toward re-election in 2005, the administration was able to momentarily turn away from the city’s economic turmoil. Bloomberg began re-examining some of New York’s social service policies, putting fighting poverty and homelessness at the top of his list.

In June 2004, Bloomberg announced an ambitious five-year plancalled "Uniting for Solutions Beyond Shelter" with the goal of tackling the complex questions of homelessness -- particularly ending chronic homelessness within 10 years -- and cutting the homeless population by two-thirds. "At its heart, this new plan aims to replace the city's over-reliance on shelter with innovative, cost-effective interventions that solve homelessness -- and to make visible headway in reducing homelessness on the streets and in shelters," said the mayor.

To be sure, there have been bumps along the way: controversial moves offering homeless individuals one-way tickets out-of-town or enforcing a never utilized Pataki-era state law charging homeless families for their shelter stay. There also was an extremely unpopular attempt to move a Manhattan intake shelter to Brooklyn. And, at a recent Working Families Party mayoral forum, media reports quoted Bloomberg as saying New York's homeless find shelters "a lot more attractive" than "permanent living situations."

But more significantly, Bloomberg’s lofty goals have not materialized. In fact, rather than cutting the population by two-thirds, the administration has seen homelessness increase substantially.

A Rising Population

According to the Coalition for the Homeless, the city's homeless shelter population has increased by 65 percent between 1998 to April 2007. Earlier this month, the coalition released revised numbers revealing the homeless shelter population reached its highest level ever at the end of September 2009. It reported "39,000 homeless New Yorkers -- including 10,000 homeless families, an all time high -- sleep in municipal shelters every night." It also found since Bloomberg took office, 45 percent more New Yorkers are in shelters every night.

These updated numbers detailed that in August "an all-time record 1,914 new homeless families entered the shelter system, and the past year has seen the largest number of new homeless families entering shelters since modern homelessness began."

Moreover, the coalition found the number of homeless New Yorkers sleeping in city shelters in fiscal year 2009 was "10 percent higher than the previous fiscal year, and 45 percent higher than fiscal year 2002, when Mayor Bloomberg took office." This data includes more than 16,500 children sleeping in shelters, a 12 percent increase since last year.

The city sees some successes in its fight to end homelessness. In its recently released Mayor's Management Report, it noted that the number of single adults in a shelter on an average day has dropped from 8,474 in 2005 to 6,526 in fiscal year 2009 and attributed some of the drop to shorter shelter stays.

The city also says it has kept many people from becoming homeless stating, "More than 90 percent of families and adults receiving prevention services did not enter the [Department of Homeless Services] shelter system." However, even by the administration's own figures, the average number of families with children in shelters has increased steadily since fiscal year 2006. In fiscal 2009, 12,959 families with children entered the shelter system, a 61 percent rise from 2005.

But its homeless policies continue to attract criticism. Chastising the mayor for thinking some people "would choose to live in a homeless shelter over permanent housing," Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum said in a statement, "Because the administration doesn’t understand the problems facing homeless New Yorkers, its policies fail to present real solutions. Policies should be reevaluated to respond to the worsening economy, the scarcity of jobs and affordable housing, and the reality that recent strategies have not been working."

The City's Tactics

In its effort to fight homelessness, the administration adopted what its Web site describes as "a first-ever effort to bring together the public, nonprofit, and business sectors in a coordinated campaign to address homelessness."

The plan was multi-faceted and integrated a myriad of city agencies. It has included an expansion of community-based homelessness prevention programs, a centralized database to better track the homeless, and ways to redirect funding and priority into prevention and away from the shelter system. It set stricter eligibility requirements, a redesigned intake process, shorter shelter stays and the creation of more supportive housing.

Deputy Mayor Linda Gibbs, former commissioner for the Department of Homeless Services and one of the advisors who helped create the new approach, said what was really innovative was that the city "flipped the paradigm." Traditionally, once someone enters "a shelter, your [other] needs are met, and then we figure out housing." Now, Gibbs said, the priority is being placed on housing needs, followed by other support services.

Patrick Markee, senior policy analyst with the coalition, though, said the administration has made mistakes from the start. While the faltering economy accounts for some of the increase in homelessness, Markee also attributes the surge to a 2005 decision by city officials to stop giving homeless families priority for federal Section 8 housing vouchers and apartments in public housing.

"From the days of Mayor Ed Koch," Markee said, "the neediest have always received a portion" of these programs. Now, non-homeless poor families receive all the priority. "It's not that they are undeserving of housing [assistance] -- there's now just anti-homeless discrimination," Markee said.

Gibbs said the administration made this shift because the supply of vouchers and public housing "is insufficient to meet the demand from the shelter system," and so it opted to give preference to "disadvantaged lower-income people." To deal with homelessness, she said, the city decided to focus "on preventive [programs] versus re-housing."

Changing Programs

In 2005, the city introduced a housing assistance plan called Housing Stability Plus, which was authorized by New York State. Gibbs said in a recent interview that the plan was "not as attractive as Section 8, where the voucher is less time-limited," but there was a shortage of Section 8 vouchers during the Bush administration when housing assistance was perennially on the chopping block.

"Housing Stability Plus," Gibbs said, "was tied to the case of a family and to receiving money and welfare... and freed up Section 8 for other community needs." Housing aid for a family decreased in value by 20 percent each year and assistance ran out after five years.

The program was "initially successful” according to Gibbs. However, the administration abandoned it two and a half years later because, Markee said, it was "a failure…and deeply flawed." The city replaced it in 2007 with Advantage New York/Work Advantage, a rent-subsidy program for homeless families that required them to work at least 20 hours a week.

Robert Hess, commissioner of Homeless Services described it in an email as, "the most generous municipal rental assistance program in the nation." According to Hess, over 13,000 leases for permanent housing have been signed under the program. "Each week 131 families sign Advantage leases, an increase of 52 percent over Housing Stability Plus levels and 79 percent over Section 8,” he said. This subsidy lasts for only two years.

Both Gibbs and Hess described how Advantage New York "incentivizes" participants, to create savings accounts and to work. The city matches dollar-for-dollar up to $250 a month in a bank account to strengthen "asset development strategy, banking skills and rewards for savings." Gibbs also said the plan gets beneficiaries "in the habit of contact with a landlord." In addition, Hess said, the program "enhances landlord participation and creates options to serve a broader population. Most importantly, it focuses on quickly returning families to their communities.”

Markee, though, disputes the administration's claims of success. What is especially galling, he said, is that there is no evidence that time-limited rent subsidies are effective, but the administration continues to use them to replace other, proven programs. The city, he charged, wants change for the sake of change. It is, he said, preoccupied with the "fetish of the new."

Markee also expressed concerns over the short time limit, noting that work advantage vouchers are expiring this year for approximately 2,000 formerly homeless families. The city "has never addressed" what will happen to these people, Markee said.

Homeless Services also invested in HomeBase, a homeless prevention pilot program that has since gone citywide. Its budget increased by 22 percent in fiscal year 2010; its client service levels increased by more than 10 percent in the first quarter of fiscal year 2010; and funding for anti-eviction services was raised by 16 percent, all according to an agency spokesperson.

The administration should not take the credit for that, though, Markee said. In an email, he wrote, "Bloomberg and City Council adopted a budget cut of $150,000 from the homelessness prevention fund," for fiscal year 2009. Bloomberg, he said, "also proposed major cutbacks to eviction prevention legal services," but the City Council restored those.

For fiscal year 2010, which began in July, Bloomberg initially called for a cut of $5 million for HomeBase prevention offices, according to Markee, but federal stimulus money then provided approximately $74 million for homelessness prevention in New York City over three years.

No Room at the Shelter?

As the cold weather approaches, capacity at shelters has also raised red flags. Another Coalition for the Homeless report claimed the city has virtually run out of space, especially for homeless single adults. It noted, "the number of homeless single adults... this year has increased by more than 7 percent -- the largest one-year increase since the 2001 economic recession." The coalition discovered on the night of Sept. 30 only two available shelter beds for homeless men and eight for women.

Gibbs described this as normal: “Capacity is always at 99 percent… and the single numbers always go up in winter; [These are] tried and true projections.”

Bloomberg pledged to construct about 12,000 units of supportive housing across the city. These would address the needs of various people, including substance abusers and domestic violence victims, Gibbs said.

Many units are currently in the works. There is "a major dent made to move the chronically homeless" from the streets and shelters, in part by learning more about, as Gibbs put it, "the who, where, their history … tracking [and] understanding their needs."

However, the coalition said, supply continues to lag behind demand. "More than half of the newly-constructed supportive housing -- 3,276 units of the planned 6,250 new units -- will not be built until at least 2011," a coalition reportsaid. That’s a different timeline than the one set out by Bloomberg, which applies until 2016.

Hess, though, said the city is prepared for future demand. "We function somewhat like an accordion, expanding and contracting as needed, so that our system does not keep space open unnecessarily at the taxpayers' expense and minimizes impact on communities, while at the same time, being ready at any moment to meet need," he wrote in a email.

Underlying all the specifics for many homeless advocates lies a question of philosophy. "One of the major reasons the Bloomberg administration gave for changing the old system of giving homeless families preference for some housing program was that it acted as a perverse incentive for families to go into the shelter system. Even without the priorities, family homelessness has escalated, suggesting either that the homelessness is driven by housing market and economic pressures pushing families out, not by perverse incentives. The priorities should be restored,” said Victor Bach, director of housing research at the Community Service Society.

With an eye on those economic pressures, Brooklyn College sociology professor Alex Vitale said in an email that the city needs to "step up and reinsert itself into housing markets through new construction of affordable housing... The amount we spend to [house] homeless families in the emergency system... is a misuse of resources that could be put into permanent affordable housing if government would embrace the reality of the current market failure and quit trying to work with for-profit landlords and developers.”

The administration often points to its record of creating new housing. Whatever its successes, though, more demand clearly exists, leaving some New Yorkers with no place to live.

Jillian Jonas is a freelance journalist focusing on local and national politics, government and public policy. She is a former national political analyst for U.P.I.