Voting Rights Revisited

When earlier this month thousands of immigrants and their supporters rallied throughout the streets of lower Manhattan, many were carrying signs that said “Today We March, Tomorrow We Vote.”

For those old enough to remember, or attentive enough to history, the sentiment expressed in those signs recalled events decades old, largely in the rural South, that led up to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But the Voting Rights Act has more connection to the recent marchers than just sentiment. Some provisions in it continue to affect parts of New York City directly. And, set to expire in 2007, they are being debated by some of the same people who are arguing over immigration.

The Voting Rights of 1965

On March 7, 1965 state troopers attacked and beat marchers in Selma, Alabama, en route to the state capitol in Montgomery. The marchers were demanding a repeal of poll taxes, literacy tests and grandfather clauses – all forces that effectively denied them their right to vote under the fifteenth amendment -— when they were met by law enforcement officers also intent on denying them their constitutional right to peaceful protest protected by the first amendment.

The attention this received and the persistence of the movement for voting rights, convinced President Lyndon B. Johnson and the U.S. Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. At the time of passage President Johnson proclaimed: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes."

While initially intended to address discriminatory voting practices that targeted African American voters, the scope and impact of the legislation has been much wider. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, and subsequent amendments, have been instrumental in blocking discriminatory practices of elections administrators and ensuring greater participation and representation for language and racial minority voters.

Sounding the death knell for literacy tests and grandfather clauses the act applied a nationwide prohibition against the denial or abridgment of the right to vote on the basis of race, color, or membership in specified language minority groups (Section 2).

From its inception, the act also prevented specified jurisdictions from making changes to their election systems without receiving “pre-clearance” from the federal government. This section, commonly referred to as Section 5 is distinct in that it is geographically specific, containing special enforcement provisions targeted at those areas of the country where Congress believed the potential for discrimination to be the greatest.

While all of Alabama, Georgia and several other states are covered, so is much of New York City, specifically the Bronx, Brooklyn and Manhattan.

One other major element of the Voting Rights Act was added in 1975 after the case had been made that voting discrimination had been suffered by Hispanic, Asian and Native American citizens even after passage of the Act 10 years earlier. Section 203 added protections from voting discrimination for language minority citizens by requiring political jurisdictions with populations of minority language voters that reached a certain size of the electorate to provide bilingual written materials and other assistance.

The Voting Rights Act in New York City

In New York City, the primary elections of 1981 were abruptly halted two days before Election Day as the courts found that the city not only failed to get pre-clearance of their newly drawn city council lines, but that the lines were drawn in a manner that would have diluted the Latino/Latina voting bloc. State Senator Carl Andrews, a former council member and original plaintiff in the lawsuit, believes it was a watershed moment in New York City’s election history: “The front page of the New York Times read â€Election Cancelled.’ People took notice…and we did away with the old system.” As a direct consequence the city’s Board of Estimate was dissolved and the city was compelled to expand from 35 to 51 members of the City Council and a redrawing of district lines to increase minority representation on the council. This ushered in greater numbers of African American and Latino council members and the city’s first ever Asian Pacific American legislator, John Liu, in 2001.

Under the Voting Rights Act, the Bronx, Manhattan and Brooklyn have been required to provide all registration and voting material in Spanish as well as English since 1975. Coverage of Chinese was applied for the first time in all three boroughs in 1992 at the same time that coverage for Spanish was extended to Queens. After the 2000 census it is now required that elections materials be available in Korean in Queens.

In testimony to Congress, Margaret Fung of the Asian American Legal Defense Fund (AALDEF) , a civil rights organization based in New York City that for 31 years has promoted and protected the rights of Asian Americans, proclaimed the voting rights act (specifically Section 203) a success story. “Section 203 has removed barriers to voting and opened up the political process to thousands of Asian Americans, many of them first-time voters and new citizens,” Fung said. “It has also aided grass-roots efforts to increase voter registration among Asian Americans.” However, according to voting rights groups the Voting Rights Act has not always lived up to its potential. AALDEF is quick to point out that language materials in Spanish, Chinese and Korean, while required at certain polling sites, are often not available on Election Day. The group also argues that with so many immigrant groups and different languages spoken in New York City, many people are not protected by the Voting Rights Act and thus ballot materials are not provided in their language.

The Future of the Act

Last year marked the 40th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act and the beginning of debate over the reauthorization of the temporary provisions that expire in 2007. While groups like AALDEF, the League of Women Voters and the ACLU have joined together in a campaign effort to “Renew the VRA” there is vocal opposition to it reauthorization, or at least to parts of it.

Representative Peter King from Long Island, sponsor of the controversial immigrant criminalization bill HR 4437, has lead an effort in Congress to block renewal of the language assistance provisions of the Voting Rights Act. Fifty-six members of the U.S. House recently signed a letter circulated by King of New York and Steve King of Iowa urging House Judiciary Committee Chairman James Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin (the other lead sponsor of HR 4437), to fight against the renewal of Section 203. The letter argues (in pdf format) that multilingual ballots "divide our country, increase the risk of voter error and fraud, and burden local taxpayers." The letter cites a November 2005 Los Angeles Times article that reported Los Angeles County had spent more than $2.1 million to provide interpreters and multi-language ballots for the 2004 election and it states that in 1996, one county in California had to spend $30,000 on Spanish ballots when only one resident requested Spanish materials.

The representatives also wrote that "federal law protects the right of all citizens to bring an interpreter into the voting booth with them if they have difficulty understanding a ballot written in English." According to King and others, that practice is "the right approach." Glenn Magpantay, staff attorney with AALDEF believes the financial argument against the multilingual provisions of the voting rights act is just a smokescreen. “It’s basically just a misguided nativist argument,” states Magpantay. “This provision allows more Americans to vote.” AALDEF is actually advocating for various measures to make it even easier to get language assistance at the polls.

We may see a debate in the coming months over Section 5 pre-clearance as well. While the pre-clearance has helped protect the rights of those in the specified jurisdictions, some argue it has outlived its usefulness, and should be allowed to expire. Others argue it should be expanded to a national level.

Doug Israel is policy director at Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham GazetteÂ

How To Make It In NYC As An Artist

It is still possible to thrive as an artist in New York City, according to several recent reports, conferences and hearings, as long as artists follow some simple guidelines.

1. Never Get Sick

A recent survey of independent artists in the city (those without a steady employer) entitled Creative Workers Count found that more than a third "experienced a significant gap in health insurance coverage in the last year," and that 75 percent of those without insurance put off seeking needed medical care. The report, which is subtitled "New York City's Arts Funding Overlooks Individual Artists' Needs," found that many artists also lack retirement plans, and "are coping with financial instability generated by erratic employment and low incomes."

2. Don't Be Born Abroad

This month, the cellist Yo-Yo Ma testified before Congress about the "extraordinarily high" barriers to foreign artists. He was talking in particular about the trouble foreign artists have been having in getting temporary visas to visit the United States in order to perform. But a few weeks earlier, Randall Boursheidt of the Alliance for the Arts testified before the New York City Council's committee on cultural affairs about the lack of opportunities for the city's immigrant "artists, both old and young…to continue to develop their work."

3. Lower Expectations

At the Creative New York Conference held earlier this month at the Museum of Modern Art, dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones contrasted what it was like in 1982 when he started his company in New York with what it is like now for dancers: “Five of my former dancers…are really depressed…they are despairing.” Two decades ago, “dancers would work for a song. Dancers did not expect health insurance, life insurance, they did not expect to have middle-class lives. Now everybody does.” That doesn’t mean they get it.

4. Make Sacrifices

At that same conference, Glenn Lowry, the director of the Museum of Modern Art, explained that artists are “willing to give up a great deal of comfort – financial, emotional, maybe psychological” to be in New York City. (But “what keeps me up at night” is that these artists will be “just as at home in Shanghai as they are in New York, if that becomes a more attractive city for their practice.”)

5. Learn To Love Inadequate, Overpriced Spaces

Those who care about the arts in New York City are increasingly alarmed at the trouble artists have in finding places to live and spaces to work – whether for rehearsing, exhibiting or performing (see Space Woes).

As bad as the problem is, what’s worse is that nobody really knows how bad the problem is, according to Boursheidt’s City Hall testimony: Nobody knows where the artists live, and how many are being forced to leave. By the time artists "exist in sufficient numbers in neighborhoods like Soho or Williamsburg or the South Bronx for the rest of the city to notice," Boursheidt said, "it's a pretty good sign the development pressure has already begun to force them out of those neighborhoods."

6. Focus On Business and Politics

There are opportunities for funding and other support from corporations, non-profit organizations and government agencies for those talented enough, and savvy enough, to make the cut. The private non-profit New York Foundation for the Arts, for example, famously offers annual "fellowships"($7,000 in cash) to about 150 individual artists in 16 categories from painting to performance art, crafts to composition. The official cultural councils of all five boroughs in the city offer grants as well, and, along with the Department of Cultural Affairs, provide other services, such as artist registries to aid individual artists in getting gigs.

But none of the cultural czars pretend there is enough funding to go around, the emphasis is support for non-profit arts organizations rather than individual artists, and there are such complicated restrictions and requirements for most grants and fellowships that an industry has grown up just to sort it all out.

"Artists need to be able to have the time to think about their art and to create," Ella Weiss of the Brooklyn Arts Council testified at the City Council hearing. "They also need to know that our society values the time they spend [creating.] The National Science Foundation funds pure research. Do we really ever fund pure art, just for the arts sake?"

"The secret shame of the art support system -- public and private funds -- is how much it talks about artists, but how little it really does to meet their needs directly," testified Ted Berger, the executive director of New York Creates, which tries to help folk and craft artists.

“An artist’s business is basically his or her art,” noted Councilmember Domenic Recchia, the chairman of the cultural affairs committee, yet “they can’t get a small business loan from the Small Business Administration.”

“There are far too many arts organizations in New York City right now,” Tom Healy of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council testified. “They don’t do the best things for the artists they try to serve.”

7. Be Perfect

A composer who teaches on the faculty of the Juilliard School observed in a television documentary marking its centennial celebration that an average graduate of law school or medical school can still have a decent career. But it is not possible, he said, for a successful artist to be only average.

8. Have Hope

Yes, there are challenges, but some smart people are trying to address them.

Health care is a problem, for example, but an innovative approach to it is suggested by a program at Brooklyn’s Woodhull Hospital, called Artists Access, in which an uninsured dancer can perform in the pediatric wing for an hour a week, or an uninsured painter can offer patients drawing lessons, in exchange for “health care credits” they can redeem when needed.

Immigrant artists are being neglected, but the Brooklyn Arts Council has made a small step towards aiding such artists through its Folk Arts program, in which it has located about 135 traditional dancers from the borough, and then matched them up with schools, senior centers and other place where they can perform.

As New York City Cultural Affairs Commissioner Kate Levin said at the opening of the Creative New York Conference, “for several generations now, New York City has provided an environment where creativity flourishes, often against all odds -- and indeed, sometimes because of those odds. This is no small feat…Creativity can be enormously robust and productive, but an individual’s vision or idea can be quite fragile. Often, we think of creative people as craving solitude, but the reason they’ve flocked to New York for so many years is because of the critical mass of individuals, institutions and opportunities.”

Â

Harlem's Heyday

The following is an edited transcript of a meeting of the Gotham Gazette Book Club on March 29 with guest Kevin Baker, author of Strivers Row.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Kevin Baker is back for the third time to round off our discussion of his history of New York City by novel. We've discussed Paradise Alley, which takes place in the draft riots of the 1860s; Dreamland, which takes place during the large scale Jewish immigration during the early 1900s; and now Strivers Row, which takes place in Harlem during the second World War.

THE HISTORY OF HARLEM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How much of the Harlem that you write about is still left?

KEVIN BAKER: Thanks for having me. Not that much is actually left physically of that Harlem. The great dancehalls – the Savoy, the Cotton Club – are all gone. Small's Paradise, a great club where Malcolm X used to hang out as a young man that figures prominently in the book, that's now an I-Hop. A lot of those things have kind of vanished.

Strivers Row – the book's namesake – is still there. It's located on 38 and 139th streets – still two of the most beautiful streets in the city.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How much of the mood or spirit is left?

KEVIN BAKER: Some of it is still there. There's still a lot of vibrancy in the community, even if it's no longer a place that really thinks of itself as the cultural capital of Black America.

By the time I'm writing the book – 1943 – the Harlem Renaissance has already been crushed by the Depression. A lot of those earlier dreams – that the black community was going to come to equal terms with whites – had already been disillusioned. But it was still a place of incredible creativity. It was still a place with amazing music coming out.

One reason that it has changed so much is that Harlem was a ghetto. That's a term we use interchangeably with "slum", but there really is a difference. A ghetto is a place where all members of a certain religion or race are forced to live – whether they're Jewish or, in this case, black. That meant that everyone lived together. At Strivers Row you had not only doctors, lawyers, ministers, but also great musicians, composers – Hubie Blake lived there, WC Handy – prizefighters, all sorts of people. Anybody who made money in the community. That feeling is kind of gone now. There's less of a black elite there.

These are the ways that cities changed. It was a good thing that New York changed – people aren't kept in this ghetto anymore – but of course something is always lost when communities change.

Harlem is still changing and probably will change for good. What this will mean, I don't know. It will probably mean some good things – money coming in. It will probably also mean some people being forced out, which isn't so good.

It will probably be much less black than it has been.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: You wrote in an article in the New York Times that Harlem was a fluke. Can you explain what you meant by that?

KEVIN BAKER: Harlem was planned for this white elite – and that's the natural place for wealthy suburbs: on the periphery of the city.

It had been this sleepy Dutch and then Irish and other white ethnic village for years. Various parts were known as Goatville or Pigville, for the different animals that would run free in the streets. So it was made first into a snappier upper middle class white neighborhood, and was then being set up to be this blockbuster white elite neighborhood. But it was being developed too fast; people weren't moving up there that fast. Developers looked around and panicked.

At the same time, African Americans were coming all the way north. They had lived in a distinctive community since the Civil War Draft Riots, basically for their own protection as much as anything else.

Developers knew they could charge black people two or three times what they charge whites in the city, because the black people had very little choice about where to live. Between 1915 and the First World War Harlem was really established.

NYC: BATTLEGROUND FOR FREEDOM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Your trilogy discusses three distinct eras in New York City history. Why these three eras as a way to explore the city's history?

KEVIN BAKER: Manhattan particularly and New York in general has always been the most contested ground in America. From the slave rebellion of 1712, the supposed slave rebellion of 1741, the many riots of the 19th century, the draft riots, to the labor struggles, and movements for women's rights, civil rights, and gay rights, all these things were really fought out here as much as anywhere in the country.

The three eras I write about were crucial moments in New York City's – and therefore America's – history. Outsider groups forced their way into what was very white Anglo society that didn't really want them here except in a completely subservient position:

The Civil War was a crucible for Irish Americans who came here because of the potato famine, as I describe in Paradise Alley. They started this Draft Riot, opposing a draft into the Civil War. It was horrible; it featured many lynchings and horrible killings of black people in the streets of the city. But it was also put down in large part by Irish police and the military. This was their decision to be part of America – and being an American citizen might mean shooting your friends and neighbors in the street.

With Dreamland, it's the uprising of the 20,000 – the garment workers and the Jewish American experience. This to me was much more about calling America on its promises. The political machinery of the city had a certain democratic feature to it, but was run as this closed Irish clan – you could get everything as a favor but nothing as a right. And here were Jews very idealistically saying "No, this is what America promises and you have to deliver on this." This led to this huge garment strike and then, after that, the tragic events of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, which is the central event of Dreamland (and which we just passed the 95th anniversary of). This would change New York and America forever.

In Strivers Row you have African Americans, who aren't immigrants as we usually think of the term – they'd been here in New York as early as the Dutch. But they are far and away the most outsider group, and this is them forcing their way into the American democracy – whether other people liked it or not.

So it's these three groups and the three folkways they pursued towards getting equal rights. These are the great stories of our democracy. So much of our culture came from Jews, Blacks and the Irish. These are hard stories; they are more brutal stories than we are generally told. But they are great stories and I've tried to capture them.

WRITING HISTORICAL FICTION

BARBARA HIGGENBOTHAM: How you do your research?

BARBARA HIGGENBOTHAM: How you do your research?

KEVIN BAKER: I did most of the research for Strivers Row at the Schomburg Center, which is a fantastic, underused research center in Harlem. I went to many of the great black writers of the time. I also did a lot of reading of the Amsterdam News at the time, which was then as now the leading weekly in Harlem. Terrific paper then, and had some great stuff particularly from a guy named Dan Burley. He was covering everything – politics, entertainment, sports, and great little mood scenes in Harlem, jotting down every word he heard, all this great slang in Harlem in the early 1940s. You can't go wrong with these sources.

With Dreamland, a lot of the terrific Jewish writers of the age helped. Haunch, Paunch and Jowl; and Michael Gold's Jews Without Money. Leon Stein's the Triangle Fire. Triangle, by David Van Drehle, came out after I wrote the book. It's fantastic.

Mostly, I used secondary sources in the books. I'm not writing history here.

I know EL Doctorow likes to say, apparently, do as little research as you can get away with. Certainly Doctorow does this better than any of us, so there's that to be said too. I like to dig in as much research as I can find. It's the little things that tell you so much – the stuff you weren't expecting to find.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: It's great that you mention those books, some of which have been previous selections in this book club, and you can read the transcripts online.

Doctorow was also a guest here, actually. He said that "history written by historians is clearly insufficient", and that novelists also have an important part to play. " The important thing is that over the years there's a consensus about literature," he said. "Some of it makes it and most of it doesn't. The books that make it have, in some way, struck people as somehow true."

KEVIN BAKER: I think that's a very good point. Whether you're writing fiction or not, truth is what you're going for. Does this ring true? The novelist is interested in truth as much as the nonfiction writer. The novelist is looking for what is true in terms of how people act and how the world of human emotions works.

JAYNA GOODMAN: Don't you think that the history that you are going back and looking at can be made up to an extent? History oftentimes is written from oral history that has been passed from generation to generation. People naturally like to exaggerate in their storytelling, so history that wasn't necessarily documented at that very moment is already an extension of the truth.

KEVIN BAKER: One of the things that labeling it fiction enables you to do is speculate more – to kind of indulge.

RACE

GOTHAM GAZETTE: One of the differences between this novel and the others in the series is that while today there isn't that much of a controversy about Tammany politics or European immigration of past eras, racial issues are still a flashpoint. Did you approach this subject differently than the subject of your past books?

KEVIN BAKER: Obviously it's something you're aware of. Race has been this undercurrent of American life for 400 years. There's no getting around it. You'd be in denial to say you're not conscious of it. But I think it is something that does not get better by being left alone. I think it's only going to be through exploring it – through fiction, through nonfiction – that we attempt to make it better. And this is a very sympathetic portrayal of the Harlem community.

Maybe it's audacious to take on the topic, but all writing is an act of audacity. I think in some ways I'm as unqualified to write about Harlem as I was to write about Jewish immigrants and Irish immigrants. I was completely ignorant of all three.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: So it sounds like you don't think there's any sense of in-authenticity about a white author writing about the black experience.

KEVIN BAKER: No. It sounds clichéd to say it, but I think there is a basic humanity that connects us. In some ways, I think it's no more audacious than a male writer writing about a woman. All writing is this attempt to put yourself into different lives, different eras. If we don't attempt that, then writing will be this very shrunken, disfigured thing.

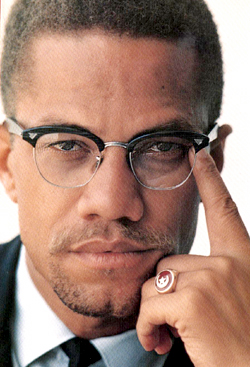

You draw upon things in your life. Malcolm X [one of the two main characters of Strivers Row] had this horrendous childhood, this very hard life. I can't say I know exactly what it's like to go through that in America. On the other hand, I was fairly poor growing up, we were off and on welfare, public assistance, and you get a little bit of a sense from that to know what it's like to be poor – to be an outsider. Again, not to the level that Malcolm experienced. But that is something you draw on.

MARTHA SOFFER: Did you get any negative feedback from the Afro-American community?

KEVIN BAKER: No, I haven't gotten any negative feedback. In fact, I have gotten more African American audience members than ever before – and glad for it. The emotion has been curiosity for the book. The worst response I got was from a white reviewer who thought I was unfair to the Irish. I'm mostly Irish myself. What can I say?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why did you decide to pick Malcolm X as the main character, someone who people know so much about, instead of picking a fictional young man who goes to Harlem, especially since what you write about happens before Malcolm X really becomes a public figure?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why did you decide to pick Malcolm X as the main character, someone who people know so much about, instead of picking a fictional young man who goes to Harlem, especially since what you write about happens before Malcolm X really becomes a public figure?

KEVIN BAKER: He is a really classic American character, caught between race in a way that kind of defines the way that America deals with race. He was a black kid who ends up going to these white schools in Michigan. He was very smart, he was like third in his class, and was elected school president. At the same time, he goes to the school dance and is not allowed to dance with any of the girls there. Physically these white guys surround him and nonviolently but adamantly wall him off from the dance floor. His whole life is about being allowed a foot in the door but nothing more. His story really sums up the frustration of race in this country in that way.

Also, the Autobiography of Malcolm X this great, iconic American text, but there are obviously parts where Malcolm is doing things for a political purpose. It's a conversion story, and a story in which he's trying to claim leadership of the Civil Right Movement in the 1960s. So he exaggerates what a bad guy criminal he was, and various other things. Oddly, he also underplays how badly he had it at home as a child. The odd thing about Strivers Row in a way is that it is using fiction to get to the truth of Malcolm's nonfiction.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is it hard to write fiction about a historical figure when almost everyone has read his autobiography and seen that Denzel Washington movie about him?

KEVIN BAKER: Yeah, it is somewhat, and I have to admit I was picturing Denzel Washington at times, and I was picturing Delroy Lindo as West Indian Archie at times, too.

I've had major historical figures in these books before, but never in as central a role. Of course you feel more of an obligation to get stuff right. In Dreamland I was really terrified about getting the stuff about Freud wrong – of course, nobody seemed to really notice it afterwards.

I think, though a lot of people have seen the movie or read the book, there are a lot of Americans who really don't know a lot about Malcolm or the Nation of Islam. They think of Malcolm as this X hat or a poster with the finger jutting forward and the "By Any Means Necessary" caption. Our heroes and our iconic figures tend to get reduced to these clichés, and I think it is a good thing to try to bring out some more of where he came from to people. I hope I succeeded at this.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: What's next?

KEVIN BAKER: I have a contract right now to write a nonfiction book about New York City baseball.

But I also have other historical novel ideas about New York, and elsewhere, and a contemporary one or two. That's kind of frowned on in publishing; they've kind of declared fiction dead. But it's not. I'll be working in this field for a while now, I think.

Â