Bake Sales Are Not Enough Anymore

Stan Levenson, a fund-raising consultant, often asks audiences at his lectures if they ever hear from the colleges or universities they attended. Of course, the crowd acknowledges. How about private schools they attended? Yes. Do they ask for donations? He doesn't even have to wait for the answer to that one.

"Every day, people are giving to good causes," says Levenson, whose clients are educators. "Why not public schools?"

Alumni of universities and private schools have been hit up for years -- most have entire departments devoted to fund-raising, called development offices -- but public schools are only starting to pursue fund-raising strategies that go "beyond the bake sale," as Levenson might say. With New York City facing tight budgets and increased pressure to provide a quality basic education to more than one million students, many members of the public school community think they have little choice but to seek private help.

When it comes to having successful alumni with deep pockets, elite public schools like Stuyvesant High School have the potential to go toe-to-toe with private educational powerhouses such as the Peddie School in New Jersey, which raised over $1.25 million in 2002. While most New York City public schools do not have the donor pool of a Peddie or a Stuyvesant, relying instead on traditional fund-raising events like carnivals and bake sales, some have begun to launch pledge drives and mail campaigns to fill in the gaps left by shortfalls in public funding. To boost such efforts, the Department of Education has launched a web site (Fund For Public Schools) where alumni of city schools can find out how to donate time or money.

The Parents Association at PS 87 on Manhattan's Upper West Side, raised approximately $300,000 in grants and donations. While the Department of Education reviews the Parents Association budget, it gives the school wide discretion in fundraising.

From a pledge drive, to auctioning off the chance to be principal for a day, to holding a neighborhood street fair and talent shows by parents and students, PS 87's fund-raising efforts help the school meet basic needs. The money buys Band-Aids and paper towels for the nurse's office, helps pay the school librarian and the "lice lady," and funds the arts program. The association's funds also cover the salaries of two kindergarten aides.

"It's pretty stark, what you'd have to do without" if there was no fund-raising, says Fredda Rosen, co-president of the elementary school's Parents Association. "You'd have reading and math."

While schools have always done fund-raising, the demand for outside money has increased. "There has always been fund-raising for public schools, but in the past, it's been for window-dressing," says Howie Schaffer, media director for the Public Education Network, a Washington-based group that lobbies for increased funding for public schools. "Now, the situation is so dire and the pain of the financial cuts is so acute that you're seeing these [funds] move into programs."

PS 87 benefits from having a cross-section of wealthy, middle class and working class families, nearly 50 percent of whom contributed to the pledge drive last year. But many schools, including those where the need may be greatest, are not so fortunate. And so some critics worry that the increased reliance on grassroots fund-raising broadens the gap between "have" and "have-not" districts.

"The danger is that if we allow elected officials to cut budgets, then only wealthy communities can ease that pain," says Schaffer.

In 1997, parents at PS 41 in fairly affluent Greenwich Village raised $46,000 to keep a teacher and hold class size down. Then-Chancellor Rudy Crew balked at the move, saying he was concerned about the effect using private funds to pay salaries of regular classroom teachers "would have on the sore issue of equity for all children throughout the system." Crew eventually compromised, saying the teacher could stay but that the community school district -- not the parents -- would pay the salary.

But issues of equity remain. While PS 87's Parents Association raises money for arts programs, one elementary school teacher on Staten Island is desperate for basic classroom supplies like notebooks, scissors, tape, glue and markers. One hundred percent of the students at the school qualify for free lunches. On the DonorsChoose web site, the instructor pleads for help: "Many children have a difficult time buying these supplies...this can cause missing work, as well as lack of self-esteem. Our students should not have to feel disadvantaged when it comes to their education."

DonorsChoose is a nonprofit that helps such underfunded schools find donors willing to pay for specific programs. Rich Yudhishthu, a teacher at Wings Academy in the Bronx, is director of operations of the web site. He and his staff review thousands of proposals from New York teachers looking for everything from "baby-think-it-over dolls" for a pregnancy prevention program, to erasers and chalk. Once a proposal is approved (and Yudhishthu notes that nearly all legitimate requests are), it is posted online in the hopes that a donor will fund it. The system is a kind of E-bay for the civic minded, boosted by word of mouth and some high-profile publicity from a profile on the Oprah Winfrey show.

Once a proposal is sponsored, DonorsChoose purchases the materials and gets them to the school, along with a disposable camera and a self-addressed stamped envelope in which to send photos of the funds in action, thank-you notes from students and a report from the instructor. Since the program's inception in the spring of 2000, over 700 proposals have been funded. More than half the faculty members at IS 125 in the South Bronx have had proposals funded.

Some fund-raising consultants believe city-wide efforts such as DonorsChoose are likely to be more productive than traditional school-based carnivals and book sales. But Levenson, the fund-raising consultant, advises individual public schools to ratchet up their fund-raising as well, setting aside some of their regular budget for a development office, much like private schools and universities do, to tap into successful alumni, parents, friends or community members. "In 18 months or two years," Levinson says, "these people's salaries will pay for themselves."

But for those in the thick of school fund-raising, Levenson ignores a valued result of more traditional grassroots fund-raisers: Community-building. "It makes the children feel like their schools matter," says Jean Joachim, former vice president of PS 87's Parents' Association, and author of Beyond the Bake Sale: The Ultimate School Fund-raising Book.

Challenging A Test The Teachers Must Take

At the conclusion of what federal judge Constance Baker Motley described as an "epic trial," discrimination claims brought against New York City's Board of Education and the New York State Education Department by black and Latino teachers and potential teachers were dismissed during the opening week of the school year.

The class action was brought in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York by Elsa Gulino, Mayling Ralph, Peter Wilds and Nia Green on behalf of themselves and an unspecified number of individuals estimated by plaintiff's counsel to be between 3,500 and 5,000. The lawsuit challenged tests introduced in 1991 as part of new state legislation mandating that anyone who did not already hold a full New York City license had to obtain state certification.

One aspect of certification entailed passing a two-part test. Plaintiffs had met all other requirements, including attaining master's degrees, but could not receive full teaching certification without passing the tests.

The lawsuit charged that the tests did not accurately measure ability or predict classroom success, and were not necessary for the teaching positions, thereby rendering the tests and the use of the tests invalid. The claims of discrimination were that white applicants passed in far greater numbers than blacks and Latinos due to cultural bias in the tests and inconsistent grading. The tests, they argued, had a disparate or adverse impact on black and Latino candidates for permanent certification to teach in New York City public schools. Without certification even people who were already teaching, some for as many as ten years, became ineligible for full licenses; others lost their temporary licenses. Some never made it into the school system. Those who did retain permanent substitute positions nevertheless experienced reduction of employment and promotion opportunities, and as much as a 30 percent decrease in salary and benefits.

"Disparate impact" in employment discrimination litigation, requires the plaintiffs to prove that the tests had an adverse effect on a protected class, the racial and ethnic groups of which they are members, i.e., black and Latino teachers and teaching candidates. They had to establish that "a particular employment practice (in this case the tests) caused a disparate impact on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin."

In fact, plaintiffs did establish this claim. In her 34-page Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Judge Motley -- who half a century ago, along with Thurgood Marshall, was counsel to the plaintiffs in Brown v Topeka Kansas Board of Education, a landmark in civil rights and education law -- found that disparity was demonstrated in this case, known as Gulino, for the first named plaintiff. The pass rates by whites was greater in a statistically significant way than that for test takers in other groups. Expert testimony showed that if blacks and Latinos had achieved pass rates equivalent to whites, their representation in the teacher workforce would have been greatly increased.

"The tests," said Barbara Olshansky, of the Center for Constitutional Rights, who represents the plaintiffs, "had a staggering effect on screening out teachers of color."

But the case did not end with the finding of disparate impact on members of a protected group.

In the second part of her analysis, Judge Motley concluded that the defendant employers overcame the disparate impact because the tests have a "manifest relationship" to the employment and legitimate connection to the goals of the teaching function.

The test contained multiple choice questions in mathematics, science and the liberal arts, and a short essay, which counted for 20 percent of the total grade. Some of the plaintiffs had passed the essay portion but not the short answers, others had lost ground on the essay. Judge Motley's decision focused on the essay.

"Defendants' decision to exclude those who are not in command of written English is in keeping with the educational goal of teaching students to write and speak with fluency. It should go without saying that New York City teachers should be able to communicate in both spoken and written English. Teachers who are unable to write a coherent essay without a host of spelling and grammar errors they pass on that deficiency to their students, both in commenting on and grading the work they turn in."

The decision did not address those who have not passed the test but continue to be employed as full-time permanent teachers and what it means to the student body that they continue to teach. Thomas Ryan, executive director of the city’s Division of Human Resources, testified that when he decided to permit these teachers to continue teaching full-time after their licenses had been revoked, he "did not believe that the teachers were harming the students in any way."

Once the court found that the tests were sufficiently job related to overcome the disparate impact, the burden shifted back to the plaintiffs, to present another practical, cost effective alternative to the tests. The plaintiffs, who had argued that the tests were invalid and unreliable, put forward a "portfolio" concept in which teachers would work with mentors and be judged on their actual performance and what it would predict about their future performance. While the court was impressed with the possibilities of that approach, suggesting that perhaps it could be used in conjunction with testing, she rejected it as an alternative.

Marie DeCanio, a Board of Education witness, testified at trial, "A test does not a teacher make. Performance is obviously the best test of whether a teacher is qualified to teach ... . On the job performance is the best way." The judge, however, disagreed.

While Judge Motley found that defendants had made an insufficient showing of the validity of the tests, she held that the test in use since 1993 "was properly validated according to professional guidelines and standards, and that they had shown that according to education professionals, of all the skills required of teachers, the ability to write a coherent essay was most important."

Plaintiffs are planning an appeal. The spokeswoman for Corporation Counsel which represented the city, refused to comment, saying she was "too busy to discuss this case." The state was represented by the Office of the Attorney General.

. Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

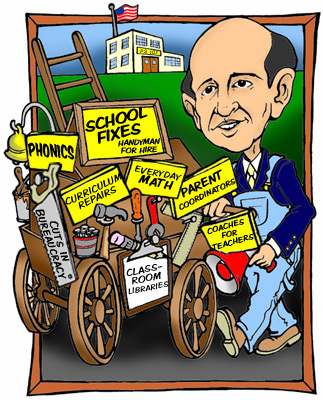

School Reforms of 2003

|

"A tremendous number of schools aren't making the grade," Peter Kerr, a spokesperson for Klein told the New York Times. "We're talking about hundreds of schools and thousands of families that are dealing with failure."

In an effort to address that, Klein and his team have spent the last 10 months completely overhauling the school system. Under their "Children First" initiative, they have changed the Department of Education's administrative structure, virtually eliminating the 32 community school districts and replacing them with 10 instructional divisions. Entire offices at the Department of Education were shut down in an effort to do away with excess bureaucracy. The mish-mash of disparate curricula that existed has been tossed out in favor of a uniform new curriculum for math and literacy.

Some see the full-speed-ahead approach as the only way to bring reform to an enormous, bureaucratic and complex system. Others say that there has been too much change too quickly, creating disorganization and confusion. Some see the reforms themselves as innovative and ambitious. Others find them untested, poorly designed and just plain wrong.

Revamping The Bureaucracy

The Department of Education recently held a "Parent Academy," a week-long training session for the city's 1,200 new "parent coordinators," one for every school, hired over the summer to boost parent involvement. Many of the new parent coordinators arrived for their training bright-eyed and energized. "What do I do with the courage and excitement I'm feeling right now?" one man said.

But the new coordinators also had plenty of unanswered questions. "It seems that there is a lack of understanding about my position and what it entitles me to do," noted one, echoing the concern of many of her colleagues. Some parent coordinators remained unsure what their budget was, or whether they even had one.

Their confusion is typical. The overhaul has created thousands of new positions even as others were eliminated. The 32 community school districts still technically exist, largely to comply with state law, but their offices have been whittled down from a few dozen administrators to just three employees

The 10 "instructional divisions" each consist of between two and four of the old districts. Until now, parents went to their district office when they had questions that could not be answered at the school level. Now, they go to "learning support centers" -- new offices in the instructional divisions.

But staff at the learning support centers may not have answers to pressing questions about registration, transfers, after-school programs and other key subjects. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum released a survey that found learning support center workers could not answer common questions. The report found, for example, that in a telephone survey of all ten support centers, none could answer questions about the documentation required to register a child.

Klein has conceded that many people in the system are learning on the job. "The fact that you don't get an answer immediately is not a major issue," said Klein. "The fact that you get an answer is critical."

Rosalyn Inman, a parent coordinator from Brooklyn, echoed Klein's sentiments. "Most of what we are going to need to know," she said, "we will learn as we go."

Advocates anticipate that, over time, the kinks will work themselves out. "Change is painful," notes Noreen Connell, executive director of the Educational Priorities Panel. "Might as well get as much as possible done in one, miserable year."

The New Curriculum

The real work of the school system, of course, goes on in the classroom. The standardized curriculum for all but about 200 of the city's so-called "high-performing schools" addresses that.

Until this year, districts and even individual schools selected their own curriculum. The lack of a standard approach posed particular problems for students who frequently transferred. With no clear guide, schools often switched from one curriculum to another, confusing students

Whatever the merits of the programs selected, some advocates say that Klein has taken a huge step forward by standardizing the programs for teaching literacy and math. "Every school was 'reinventing the wheel,' and some failing schools were reinventing the wheel every two years and doing it very poorly," said Noreen Connell. "Now consistency and depth in delivering instruction is a real possibility for most schools."

In literacy - reading and writing - the curriculum teaches children to read by having them read books that interest them. Under this approach, called "balanced literacy," Dick and Jane are out, replaced by classroom libraries where students can select books at their particular reading level.

The math program emphasizes problem solving over memorization and focuses on the way math is used in real life. Students use "manipulatives" such as blocks, rods and games to learn math concepts. For example, rather than being presented with a sheet of problems to learn addition, first graders might play a game with dice.

The new curriculum relies on what are generally viewed as progressive ideas about teaching. The math program, called "Everyday Math," emphasizes "understanding concepts rather than mastery of basic operations," and balanced literacy "focus[es] more on children working among themselves than on direct instruction," James Traub wrote in the New York Times.

Many experts have criticized the choice of the programs, charging that they do not give enough weight to traditional teaching methods. Using such programs in New York City schools could be "a disaster in the making," Sol Stern wrote in City Journal, "not least because the children in the targeted schools are mainly poor and minority - the very population historically most damaged by such methods."

Writing in the New York Sun, Bas Braams of the NYU mathematics department, faulted "Everyday Math" for offering a confusing array of methods for basic arithmetic, jumping around from topic to topic, and for introducing calculators in kindergarten.

More debate swirled around phonics, which teaches kids to read by emphasizing the relationship between letters and their sounds. Conservatives, including many in the Bush Education Department, favor this approach. But rather than endorsing a full-fledged phonics program, Klein and his educational expert, Diana Lam, decided to give students in lower grades a half hour of phonics instruction a day in addition to their other reading and writing work. Critics promptly charged that the program they selected -- "Month by Month Phonics" -- was untested, and, in fact, not focused on traditional phonics methods at all. In the wake of such criticism and threats from the Bush administration not to provide funds for the program, the school system selected a more traditional phonics program to supplement "Month by Month Phonics."

Klein has pointed out that the curriculum he and Lam chose is already being used in some successful city schools. Some of the city's highest performing districts, such as district 26 in Northeastern Queens, use balanced literacy. In March, the New York Times profiled P.S. 172 in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, a school that was already using both "Everyday Math" and balanced literacy, as well as phonics. The school has good test scores, despite a disadvantaged student body.

In discussing the math curriculum, school principal Jack Spatola said, "The beauty of the program is that it individualizes teaching and learning. That helps kids to understand a process rather than just regurgitating it."

Teacher Training

Beyond the substance of the new curriculum, many principals and experts have expressed doubts about how teachers were trained.

Over the summer, teachers received a compact disc that provided an overview of the new curriculum. And this year school started a few days later than usual to give teachers four days of training about the new programs. To help teachers as they go along, the Department of Education has hired math and literacy coaches for each school using the new programs.

Stephen Porter, the principal of PS/IS 226 in Bensonhurst, thinks the uniform curriculum will improve continuity as students move from grade to grade. But he does not think teachers had enough time to become accustomed to the new programs before putting them into use. While the quality of training was good, teachers need more time to absorb it, he said. "You want [teachers] to really think about it," Porter said. "Right now, it is difficult for them to think, they are working so hard just to keep abreast of what is going on. They are trying to keep a day ahead of the kids."

But Robert Klein, a local instructional supervisor in Queens' Region 4, says that the new programs have gotten off to "a smooth start... Teachers have organized rooms and are using the new strategies."

While the new curriculum went into effect very quickly, it will take far longer to see the effect of the reform. "Instructional change is hard," said William Stroud, the principal of the Baccalaureate School for Global Education in Astoria who worked on the new curriculum. "People are looking for a quick fix to the achievement problem. If our expectation is that we are going to see results in one year or two years, we are going to be disappointed. We should expect to see improved student achievement in three to five years."

Given the magnitude of the changes, what was most striking on the first day of school was how much remained the same. Students, many toting new backpacks laden with supplies, struggled to find their classrooms and loudly called out to their friends. Teachers welcomed students as principals tried to deal with the customary confusion of making sure children ended up where they were supposed to. Asked if this year seems different from last, a tenth grader at the Baccalaureate School shrugged her shoulders and offered, "I have a new math teacher."

But the city still has a huge student body with many needs, and a lack of resources. The perennial problem of overcrowding may be even worse than usual this year, prompting the United Federation of Teachers to file grievances charging the classes are so big they violate the teachers' contract. And so, the real test of Children First will be to see whether it can improve performance despite these immense challenges.

Deborah Apsel is a reporter with Inside Schools, a web site published by Advocates for Children.

Related Article

Put Class Size on the Ballot

The New York City public school system is undergoing major changes. But little progress has been made, writes Leonie Haimson, to fix the system’s most serious problem: large classes.