School Security

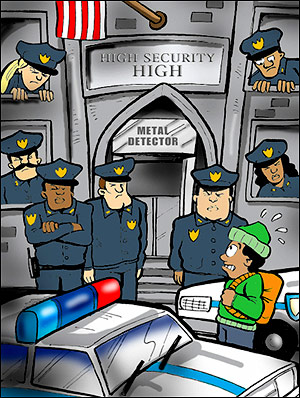

Students leave Washington Irving High School under the gaze of the famous New Yorker for whom their school is named, the author of Rip Van Winkle. But Rip might be amazed at what has happened to the school, which is now patrolled by more than a

dozen police officers and security guards. On a recent afternoon, police cars, police trucks, even police sports utility vehicles lined the street outside the school.

Students leave Washington Irving High School under the gaze of the famous New Yorker for whom their school is named, the author of Rip Van Winkle. But Rip might be amazed at what has happened to the school, which is now patrolled by more than a

dozen police officers and security guards. On a recent afternoon, police cars, police trucks, even police sports utility vehicles lined the street outside the school.

"Everywhere you go you see a cop," said student Monica McAllister on the sidewalk.

"It's like a prison," added Diabe Diaman, a classmate.

A police officer called out from his car, "let's go, ladies and gentlemen," and then sounded his siren.

The massive police presence at Washington Irving is repeated at the 11 other public schools that were deemed this month the most dangerous in the city. (see box). Flooding these dozen schools with police is just one part of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's major new campaign. "We brought down crime in the city; everybody said it couldn't be done," Bloomberg said at a press conference. "There's no reason why we can't bring down crime in the schools."

No one disputes the need for safer schools. "The question is, does having police in class make schools safer?" says Jill Chaifetz, executive director of Advocates for Children, a non-profit group that works on education issues. "There's no indication that it does."

THE PROBLEM

By most accounts, violence and crime in schools have actually declined in recent years -- both nationally and even locally. Serious crimes have gone down in NYC public schools by 23 percent in the last two years, and though it has crept back up a bit since July, Bloomberg says "we are not having a crime wave in the schools."

School RulesThe discipline code for New York City schools, distributed to all students, is a 26-page book ranking infractions from level 1 (not wearing a school uniform, if one is required, or being late) to level 5 (selling illegal drugs or using a firearm in school). Offenders face a range of penalties from a reprimand to suspension. A principal may suspend a student for no longer than five days. A regional superintended may suspend a student for up to a year and can even expel a general education (i.e. not special education) student who has turned 17. Any student facing suspension of more than five days is entitled to a hearing. Advocates for Children offers a number of manuals for parents of students facing suspension. All suspended students must receive some kind of instruction. For short-term suspensions, this can be provided in the school either during the normal school day or after school. Students who are chronically disruptive can be assigned to New Beginning Centers. So-called SOS - for Second Opportunity Schools - serve students with long-term suspensions usually for being violent. School officials say that such programs are designed to prepare a child for returning to regular classes. |

But some question this optimistic picture. "No matter what the Education Department is saying, there is a growing problem in school violence," said City Council Speaker Gifford Miller, who is a likely mayoral candidate.

Clearly problems exist. Assaults on teachers rose from 105 in the 2001-2002 school year to 149 in 2002-2003, according to the United Federation of Teachers, and have risen another 40 percent since September.

Under the promise of anonymity, principals and others complained in a survey by Congressman Anthony Weiner's office this fall that school officials were slow to approve requests to suspend students. Because of the delays, a student who had committed a serious offense could remain in school for up to three weeks before being punished.

Delays have been blamed on the mayor's reorganization of the city school system. Officials in the five high school district offices used to process requested suspensions within 48 hours. But Bloomberg got rid of those offices, and the centralized office assigned to review suspensions seemed unable to handle them promptly.

Meanwhile, newspapers have fueled the sense of urgency by focusing on individual horror stories: A pregnant woman suffered serious injuries when she was struck by a chair dropped or thrown from an upper story window at Washington Irving. A 16-year-old student at Beach Channel High School in Rockaway smashed his former girlfriend's head into a glass trophy case. A ninth-grader tried to bring a loaded semiautomatic handgun into Adlai E. Stevenson High School in the Bronx.

Even a few incidents such as these affect education, distracting teachers and frightening staff and students alike. And many incidents that fall short of crime - verbal harassment, for instance, or shoving - can intimidate other students.

Disorderly schools cost money - as much as $240 million a year, Marc Epstein, a dean of students at Jamaica High School, wrote in the New York Post. To arrive at that number, Epstein estimates that literally hundreds of deans in city high school and middle schools spend most, if not all, their time on discipline and safety.

THE ANSWER(S)

School violence has challenged New York City mayors at least since the Lindsay administration. In 1969, the situation at Franklin K. Lane was so extreme that the city shut down the school temporarily. Today, Lane is on the list of 12 dangerous schools.

During his tenure, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani tried to address the problem by putting school security agents under the supervision of the New York police department. Two years ago, after two students were shot and seriously wounded at Martin Luther King Jr. High School in Manhattan on the birthday of the civil rights leader, the school chancellor, Harold Levy promised to improve security.

The most recent school safety plan borrows terminology and techniques from the efforts of the last 12 years to bring down street crime.

Bloomberg says his plan will:

- Identify particularly dangerous schools - so far, 10 high schools and two middle schools. According to statistics released by the mayor's office, these 12 schools together accounted for 13 percent of all serious crime in New York City's more than 1,200

public schools. The police department will assign approximately 150 additional officers to the schools, and teams of police and Department of Education officials will evaluate attendance, safety and discipline. Calling these "Impact Schools," the mayor

said he was modeling the plan on Operation Impact,

which, he said, brought down crime by deploying additional police to specific locations in the city where there had been a high incidence of crime.

- Use the city's computerized crime tracking COMPSTAT system to identify dangerous schools.

- Crack down on minor offenses, such as cursing and insulting other students. Taking a page from the broken windows approach to fighting crime, which holds that "quality -of-life" offenses

set the stage for more serious infractions, the mayor says that disruptive students "can create an atmosphere conducive to more serious incidents."

- Focus on habitual troublemakers. Students with at least two suspensions in two years could be immediately removed from school, even for a non-violent offense, such as smoking, cursing or being disruptive on a school bus. Here, the mayor is using the

model of Operation Spotlight, which targets people who repeatedly commit minor crimes. "Just as 'Operation Spotlight' has resulted in the quick removal of chronic miscreants from

our streets," said the mayor, "Spotlight students will be quickly removed from our schools."

- Create more centers for suspended students. This would include centers in school for students suspended for a matter of days and so-called "New Beginnings" schools for chronically troublesome students. The program also calls for putting more students

in the SOS, for second-opportunity schools, that serve students under long-term suspension, usually for violent offenses.

- Streamline the suspension process. The mayor promised that all suspensions will once again be reviewed within five days.

- Have principals take increased responsibility for making their buildings safe.

THE RESPONSE

Some politicians and educators hailed the mayor's program. "It's a good plan," said City Councilmember Peter Vallone. "It shows what happens when the mayor and [police commissioner] Ray Kelly get together. They come up with some good ideas."

But others had doubts.

"If it's done well, students will feel more safe," said Richard Arum, an associate professor at New York University's Steinhardt School of Education and the author of a book on school discipline. "If it's done in an authoritarian way, it will alienate more kids."

The Dangerous SchoolsThe 12 schools listed as being the most dangerous in the city and receiving extra police are: Bronx Brooklyn Manhattan Queens |

"Many of the 12 schools on the mayor's list already feel like minimum-security prisons, with metal detectors at the entrance and security officers with billy clubs and squawking walkie-talkies," Clara Hemphill, editor of Inside Schools, wrote after the mayor's announcement.

Even students in generally safe schools gripe about what they see as abuses by guards -- being questioned in the halls, not being allowed to hang out near the school building when classes end for the day, and being treated rudely. This is nothing especially new -- two years ago at relatively safe Midwood High School, a boy approached the security desk asking if he could speak to someone about how to enroll in the Brooklyn school, only to be told brusquely that he had to leave immediately: "People in there have better things to do than to talk to you," a guard said. But more and more students seem to be complaining about the security procedures. Metal detectors at some schools and the checking of identification create long delays, forcing them to arrive very early at school.

For adults, though, the question usually comes down to whether all these measures will make schools safer. By focusing on 12 buildings, the mayor's plan does not cover enough schools, says Eva Moskowitz, chair of the City Council Education Committee. "What about school number 13?" she asked. "If you have ten fewer incidents, you get no police presence."

To address problems at every school, Vallone, who chairs the council's Public Safety Committee, has proposed a bill to place security cameras at all entrances to all schools. "I have not spoken to anyone who does not think cameras in schools are a good idea," he said. Many, including people in the administration, do object to the projected cost, which Vallone estimates at $100 million.

Other proposals call for improving conditions for the 4,000 school security officers. Although the police department supervises school security, the officers are not members of the New York City Police Department. At a recent rally sponsored by Teamsters Union Local 237, which represents the officers, speakers complained of poor equipment, low pay - it peaks at about $28,000 a year regardless of seniority and the officers have not had a raise in three years - and few, if any, opportunities for advancement.

"It's a rewarding job," says office Joanne Johnson, but it's also difficult and dangerous. The officers, she says, are fighting for more money, for better equipment and for more respect, particularly from the police department. "They look at us like they wouldn't do what we do."

HELPING DISRUPTIVE STUDENTS

What becomes of the disruptive and particularly the violent student forced to leave school? "Will suspensions help?" asks Jay Gottlieb, a professor at the Steinhardt School. "Yes, but not the kids who are suspended."

National experts agree. Suspension "contributes to the achievement gap and starts the chain of events that leads to kids dropping out," David Richart, the author of a Kentucky study on suspension told NEA Today.

Over the years, city schools have launched a number of programs for disruptive students. One, the so-called "600" schools, was closed by court order because the overwhelming majority of students in them were black and Hispanic boys. Others still exist, although with new names.

Concerns still exist over the makeup of the student body at the special programs. More than 90 percent of students at Second Opportunity students last June were black or Hispanic, compared to 73 percent of the general school population, according to Advocate for Children. Over 70 percent were male, and 43 percent were receiving special education.

Joseph Collins is director of education for The Door, a Second Opportunity School, run by University Settlement. His program serves students who have been suspended for a year. It provides an academic program as well as counseling and less traditional approaches, such as music and art therapy - all aimed at preparing youngsters to return to a regular school. Because the program is new, few statistics exist on its success, but, Collins says, "kids are coming here every hour, every day all year so we must be doing something right." On an average day 75 percent of students attend.

VIOLENCE PREVENTION

Whatever the merits of such programs, it would be better to keep kids from getting into trouble in the first place. Beyond increasing security, what can - and should - be done?

Some problems, such as an era in which there is less adult supervision in general, fall beyond the reach of school officials, says Arum. But other problems can be addressed.

Teachers need more training in how to control classes, says Jay Gottlieb "Many kids don't know the appropriate way to behave in the classroom," he says. "It really has to be taught to kids, and it's not." Such instruction he says must take place in elementary school and requires the commitment of principal.

Others say discipline problems reflect basic problems in city schools, particularly high schools. Certainly the 12 "Impact" schools are not paragons of academic excellence. Students at Washington Irving fault the quality of teaching they receive. Only 55 percent of students there graduate in four years, and just half pass their English Regents. Other schools show even more dire results. At Adlai E. Stevenson, for example, only 37.1 percent graduated in four years and a mere 21 percent passed their English Regents.

And other problems confront these schools. Sheepshead Bay High School is "so sprawling and confusing that even the principal has difficulty finding her way around," says the Inside Schools web site. "Corridors are so crowded during class changes that kids complain the human gridlock makes them late to class."

"Almost every one of the high schools on the list is severely overcrowded," says Jill Chaifetz noting that one, Christopher Columbus, has so many students that it is on triple session. Chaifetz says smaller classes and smaller schools would make for safer classes and safer schools.

Many students, says Arum, have no interest in traditional academics. To make the curriculum "more relevant and engaging" to such students, he says, schools should bring back vocation education. "The purpose of vocational education," he says, is not so much to prepare students for particular jobs as "to get people to interact with school in positive ways."

Like Arum, Collins says that high school education must change to keep students from ending up in programs like his. "The system needs an overhaul," he says. "The culture of kids today is very different from five years ago and you need to address that." As an example, he says that The Door has a recording studio and uses many youngsters' enthusiasm for hip-hop to get them to become engaged and work on language.

In this era of standardized testing, uniform curriculums and little money, the chances for many of these changes seem remote. And many would argue that nothing will work unless students feel safe and secure in their classes and corridors. The mayor seems determined to do just that. "If I have to put a police officer next to every kid, we will," he said.

New York's Children Left Behind?

Two years ago this month, on January 8, 2002, President Bush signed into law the No Child Left Behind Act, an extensive revision of the federal education law. The Act proposed to improve the academic achievement of all students. It pledged additional funding for quality teaching, proven instructional methods, choices for parents of students in low performing schools, and stronger accountability for achievement, including closing achievement gaps among different groups of students.

No Child Left Behind Act, which passed Congress with broad bipartisan support, is the latest reauthorization of the federal law on elementary and secondary education. First enacted in 1965 as part of President Lyndon Johnson's "War on Poverty," the law encompasses Title I, the federal government's largest program of school aid for disadvantaged students. (For a full description of the law's requirements see my November 2002 column, "No Child Left Behind.")

Though over half of New York City's public school students are poor, the federal government currently provides only about 10 percent of New York City's education budget. The rest comes from state and city funding. No Child Left Behind has brought some additional funding to the New York City schools, but it has itself never been fully funded. According to Rep. Anthony Weiner (D-New York: District 9), this year New York City will receive $400 million less than it was promised in No Child Left Behind. In an already resource-starved system, this disparity has led many parents, educators, advocates, and elected officials to believe that the new law demands changes without offering the means to implement them.

In the meantime, schools and districts must meet "annual yearly progress" targets for the school as a whole, as well as for separate demographic subgroups of students. Schools receiving federal poverty funding (called Title I schools) face consequences that escalate for each year of failure to meet these targets. These consequences range from providing alternatives, including transfers and tutoring, for students in failing schools to taking over or closing schools.

In January 2003, New York was among the first states to receive approval for its plan to meet the law's new accountability provisions, thanks to a strong state accountability system already in place. Over the past year, the New York City Department of Education has worked with the state education department, and with districts and schools, to fulfill such key provisions of No Child Left Behind as disseminating information about school performance, recruiting and hiring highly qualified teachers, and notifying hundreds of thousands of parents about their new options.

According to Ira Schwartz, a state education department official who monitors the city's compliance with No Child Left Behind, the New York City Department of Education has devoted considerable resources and made a good faith effort. But, Schwartz says, for large urban systems with high percentages of low income students, it is a hard law to implement. On a national scale, he believes, New York City would grade high compared with other large urban systems.

This year, for the first time, schools are being held accountable for the achievement of students of different races, students with disabilities, students with limited English proficiency, and low-income students. Schools have to report separate test score data for each of these subgroups and are not considered successful unless all groups meet test score targets. This information will appear on next year's school report cards.

In September, in compliance with No Child Left Behind, the state education department announced this year's list of "schools in need of improvement." The list includes schools that have missed their progress targets for two consecutive years or more. Of the 527 schools on the list, 347 are in New York City. Another 123 city schools that receive no federal poverty funding are listed as "requiring academic progress" because they failed to meet test score targets.

Under the parent choice provisions of No Child Left Behind, when a Title I school has been placed on the "schools in need of improvement" list, its students are entitled to transfer to a better school. After a second year on the list, its low-income students are entitled to free tutoring services. In principle, these options should offer students in low performing schools an important lifeline. In practice, as we shall see, it is not so simple.

In New York City, schools throughout the system are overcrowded. Schools in need of improvement are often found in neighborhoods where many of the schools are low performing. In the first year of the law, students entitled to a choice of schools were only offered options within their community school district, which meant that students in some districts were given very few and very poor options. Later, under pressure from parents and advocates, this policy was revised, and this year students were offered eight choices from schools throughout the city.

Still, only about 8,500 of the approximately 250,000 eligible students were able to exercise their option to move. Some parents found that the schools they were offered for transfer appeared no better than the schools they were entitled to leave. Moreover, many school options were far from students' homes.

New York City Council Member Eva Moskowitz, chair of the Council Education Committee, believes that the Department of Education must work much harder to provide fair access to the important right to school choice. "Middle class families have always had access to choice," she says, "but it is new to poor families. As a result, their children have been trapped for years on end in locally zoned schools that are failing. No Child Left Behind has the potential to say that they don't have to wait years for reform; they can go to a better school right now."

Because this idea is so "revolutionary" for poor people, Moskowitz believes that the Department of Education must conduct vast communications and public relations efforts to ensure that they know and exercise this right. She also called on the city to institute a "sibling policy" to make school transfers more family-friendly. But the city rejected the idea, so families with more than one child in a failing school will continue to receive two different lists of school choices.

Many high performing schools are already at or above capacity. This year, the transferring students increased overcrowding in a number of schools. Other large school systems, like Chicago, granted only a fraction of the transfers requested to avoid overcrowding. The Department of Education is reportedly looking for alternatives to mass transfers.

Under No Child Left Behind, low-income students from schools that stay on the failing list (In PDF Format) for a second year are also entitled to "supplementary educational services," extra academic help that can include private one-on-one tutoring. These free services may either be provided by the school district or by a community-based organization or private company.

Last year, of over 200,000 students eligible, only some 30,000 signed up for free tutoring. According to a report by Advocates of Children of New York, English language learners and students with disabilities were even less likely to get services than other students because of the city's poor communication with parents and tutoring providers, short deadlines for registration, and a lack of appropriate services available. Of the students who received tutoring, nearly all got services from the school system itself.

This year, Advocates for Children of New York and its allies, like City Council Member Moskowitz, called for changes so that families knew about their children's right to extra academic help, had sufficient time to register for tutoring, as well as got choices among providers so students were not simply required to spend more time at their failing schools.

This fall, the Department of Education improved its outreach to parents, relaxed enrollment deadlines, and announced that 40,000 students had enrolled for services. Advocates point out that this still only amounts to 19 percent of those eligible for free tutoring services and urge expanded measures for continued improvement.

While the New York City Department of Education struggles to comply with the many provisions of No Child Left Behind, critics of the law complain that its requirements create a distraction from the real challenges the city's school system faces. The new federal law may have created some new opportunities for a relatively small number of the city's l.l million public school students, but most of its requirements do little to address the city's underlying problems of chronic underfunding, an inability to attract and retain good teachers and principals, overcrowded and unsuitable facilities, and a lack of services and support for the many students with broader educational needs.

Representative Weiner, for one, believes that No Child Left Behind has left the city's schools worse off than before. "The law visited all these new regulatory requirements on the city schools and didn't give them the resources to accommodate the change," he says. "No Child Left Behind is really just an elaborate regulatory Kabuki dance to cover the fact that the New York City schools have been shortchanged."

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and Director of Policy Development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a not-for-profit coalition working to reform New York State's education finance system to ensure adequate resources and the opportunity for a sound basic education for all students in New York City. The views expressed are her own.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and Director of Policy Development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a not-for-profit coalition working to reform New York State's education finance system to ensure adequate resources and the opportunity for a sound basic education for all students in New York City. The views expressed are her own.

School Contracts: Do They Serve The Students?

Last month, the education committee of the New York City Council held a controversial series of hearings examining school system labor agreements, the contracts whose little-known details, or "work rules," govern much of the day-to-day workings of the city's public schools. The hearings aimed to inform the public about the city's contracts with the major unions that represent school custodians, teachers, and administrators and to explore whether some aspects of these contracts created barriers to improving instruction.

All three union contracts for school employees have expired and must be renegotiated.

Education committee chair Eva Moskowitz, the council member who spearheaded the unprecedented hearings, told reporters that union officials and others had pressured her to cancel them. She persisted because she believed that was her duty to turn attention to what she called the "elephant in the room," contract rules that serve the adults in the schools rather than the children.

Testimony from the Department of Education and school personnel claimed that good schools flourished in spite of the contracts, not because of them. Witnesses, some of whom testified on tape rather than in person, with voices disguised, said that a number of aspects of the contracts were problematic.

The custodians' contract contains a number of seemingly arbitrary divisions of responsibilities that create inefficiencies and long waits for maintenance and repairs. For example, custodians are only permitted to paint school walls to a height of ten feet. Above ten feet is someone else's responsibility. Custodians are responsible for changing light bulbs, but ordering new bulbs is someone else's responsibility. The hearings also revealed provisions in the custodians' contract that offer possible financials incentives for doing less improvement work, as well as provisions that limit accountability of custodians to their school's principal.

The teachers' contract makes it hard to remove poorly performing teachers. Though the last contract agreement streamlined the official dismissal process, principals and others testified that amassing the evidence necessary to initiate that process takes years. The teacher salary structure set up by the contract makes it impossible for the school system to offer higher pay to attract teachers in shortage areas, such as math and science. The contract also allows teachers with seniority to transfer to fill vacancies in schools anywhere in the city without screening or approval from the school. Furthermore, the receiving principal may not even see the teacher's file from the old school. This has two consequences: experienced teachers gravitate toward higher performing schools, and poorly performing teachers can be pressured to move on rather than risk an unsatisfactory rating. In addition, the contract agreement known as Circular 6 prohibits teachers from conducting homerooms and from monitoring halls or lunchrooms.

The contract that governs supervisors and administrators has similarly troublesome transfer policies. Dan Weisberg, the executive director of labor policy for the Department of Education, testified that the administrators' contract made it nearly impossible to fire incompetent principals and assistant principals. He also said that seniority rules made it difficult for the city to manage administrators effectively.

Labor officials criticized the new policies of Chancellor Klein's Children First initiative, as well as chaos and confusion surrounding its implementation this fall. They complained that the new policies micromanaged schools and classrooms, tying teachers' and principals' hands. United Federation of Teachers president Randi Weingarten said that new classroom rules were forcing teachers to become "robots." Council of Supervisors and Administrators president Jill Levy called Children First a "reign of terror."

Weingarten and Levy also criticized the mayor and the chancellor for attacking contract provisions but refusing to come to the bargaining table to negotiate a new contract. The UFT has specifically accused the Department of Education and its chancellor of "poisoning the atmosphere for good-faith bargaining in an attempt to divert attention from their failure to implement their new educational policies and blame the union and the contract for those failures."

Both union heads accused the council hearings of maligning committed, hardworking school personnel.

Throughout the hearings, city council members repeatedly reminded education officials that the city had agreed to each provision it was now complaining about. They urged school officials to act quickly to remedy the problems they saw.

Following the hearings, a number of city politicians, including City Council Speaker Gifford Miller, called on Mayor Bloomberg to renew efforts to negotiate new contracts with the unions. The teachers union has filed a formal complaint against the Department of Education for refusing to negotiate.

Study Quantifies Impact of Teacher Transfer Policy

A new analysis of the allocation of teachers in the city schools shows once more that schools with the neediest students are routinely staffed with the most inexperienced teachers. The report, issued by the Industrial Areas Foundation, Metro New York, demonstrates that this practice amounts to a significant resource disparity between poor and middle-to-upper-class schools within the city. It holds both the teachers' contract and school system budgeting policies to blame.

Under the terms of the teachers' contract, the most senior teacher who applies to fill a position must be hired. Over time, senior teachers gravitate toward the wealthier, higher-achieving districts. The school system reinforces this trend with its formula for allocating money to districts. Instead of allocating districts a certain amount to pay for teachers, it allocates teacher positions, "holding the districts harmless for differences in teacher salaries."

One possible solution, according to the report, would be to allocate to districts the average teacher salary for each teacher. This would give high-performing districts a financial incentive to hire a mix of experienced and new teachers. Plus, poorer districts that could not attract enough experienced teachers would have the option of hiring more teachers and reducing the teacher-pupil ratio.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and Director of Policy Development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a not-for-profit coalition working to reform New York State's education finance system to ensure adequate resources and the opportunity for a sound basic education for all students in New York City. The views expressed are her own.

Jessica Wolff is a public school parent and Director of Policy Development at the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, a not-for-profit coalition working to reform New York State's education finance system to ensure adequate resources and the opportunity for a sound basic education for all students in New York City. The views expressed are her own.