Albany Puts the Brakes on Faster Buses

"No one has done more to preserve, protect and defend gridlock in New York City than Assemblyman David Gantt (D- Rochester), and Tuesday he made sure that bus riders are condemned to commuting at a crawl," the Daily News said earlier this week after Gantt, the chair of the Assembly's Transportation Committee, effectively killed a bill allowing enforcement cameras for city bus lanes, at least for this legislative session.

Gantt blocked a bill (S7229 Golden / A10233 Bing) championed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, as well as scores of New York City advocacy groups, that would have allowed the city to use cameras to enforce restrictions designed to keep cars and trucks out of bus lanes. Supporters saw the measure as key to the success of the bus program. "Bus lane enforcement cameras are a key element to keeping bus lanes clear and bus riders moving," said a memo by the Campaign for New York's Future, an umbrella group of city advocates.

Both the mayor and advocates were disappointed.

"Gridlock will not simply disappear on its own," said a spokesman for the mayor. "The lack of action without any explanation ... means that transit riders can expect slower buses and longer commutes."

Wiley Norvell, a spokesman for Transportation Alternatives was a bit more pointed: "Twice this spring," he said, referencing the Assembly's recent decision to not even vote on congestion pricing, "Albany has been offered the opportunity to decongest our streets and get our city's 2.7 million bus riders moving. Twice they've stood in the way. After an unprecedented year focusing on the city's transportation crisis, we're left wondering if our legislators even grasp the problem."

So What is the Problem?

Gene Russianoff, senior attorney at the Straphangers Campaign, frequently says that it takes less time to get from New York to Philadelphia on Amtrak than to go from Harlem to City Hall on the M-15 bus.

Russianoff, of course, is an advocate with an agenda. But sweltering Staten Islanders standing around X-1 stops in Midtown express almost identical sentiments.

"On a bad day, and there are a lot of bad days, it's usually around two hours. On a terrible day, I've been onboard and standing for more than four hours," said Jim Litterelle, a financial consultant who has commuted from New Dorp, Staten Island to Midtown Manhattan for the past five years. Four hours, by the way, is more like an Amtrak ride from New York to Boston.

Litterelle's story is by no means unique. Many of city's bus commuters have contended with multi-hour traffic tie-ups for years. The Straphangers Campaign and Transportation Alternatives have been doling out Pokey Awards to New York City's slowest buses since 2002, and "changes in bus speeds since 2004 have generally been too minor to demonstrate significant trends," according to the Pokey's most recent press release.

Speeding the Buses

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the city Department of Transportation and advocates, however, have seen the glimmering of a green light at the end of the congested tunnel. The city's first Bus Rapid Transit project, called Select Bus Service, is scheduled to start along the Bx 12 route in Northern Manhattan and the Bronx on June 29. With enhanced bus lanes, payment before boarding, increased spacing between stops, and priority for buses at traffic lights, many believed this new route, along with four other planned Select Bus Service corridors, would act as surface subways, providing a faster, more reliable and appealing bus commute.

Bus lane enforcement cameras were a crucial part of the Select Bus Service plan.

"Bus Rapid Transit needs to be rapid and for that to happen we need an easy way of keeping autos out of the bus lane. Cameras are a simple way of making that happen." Russianoff said.

Judging by the success of bus lane cameras in London, Russianoff is right. Since the technology was first deployed there in 1997, the length of average bus trips was reduced by 10 minutes, wait times decreased by 15 percent, bus speeds increased by 12.6 percent, and bus lane violations decreased by 60 percent, according to the most recent Transport for London reports.

According to a Department of Transportation briefing memo, depending on the bill's final language, the cameras, which would be used exclusively along the Bus Rapid Transit demonstration corridors, could be installed on buses, at fixed locations or on mobile units along bus lanes. Between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m., the cameras would capture photos or videos of vehicles violating bus lane regulations. The owner of the offending vehicle would receive the equivalent of a parking ticket in the mail. No points would be assessed against the driver.

In many ways, bus lane enforcement cameras would be similar to the city's red light camera program, which has had a great deal of success since implemented in 1994. It has not only saved traffic officers time, but early studies showed a 40 percent to 60 percent reduction in speeding violations and a 24 percent reduction in injuries where the cameras were installed.

The Opposition

Civil liberties advocates have traditionally voiced concerns about the deployment of cameras for enforcement purposes. The New York Civil Liberties Union carefully watched this particular bill and decided it could accept it. "We talked a lot of things through with city DOT and developed a good framework for addressing privacy concerns," said the group's legislative director, Bob Perry. "We would not oppose the bill. We would offer support with amendment, because we felt we were engaged in a good faith effort to get privacy principles reflected in the bill."

Gantt has long opposed traffic enforcement cameras, often citing privacy concerns as his reason. But, with such a blessing from reputable privacy advocates, what concerned him this time around?

To add to the confusion over his thinking, the Assembly member recently introduced a piece of legislation that "would allow any community in New York State to install red light cameras ... and to boost government revenue from fines levied on violators," according to a recent article in the Poughkeepsie Journal.

Gantt did not respond to multiple requests for comment, but several news outlets (click here and here) have reported that his red light camera legislation was written as a "contract bill," a bill that favors a particular lobbyist. Robert Scott Gaddy, Gantt's former counsel and the principal of Excelsior Advocates LLC., represents CMA Consulting Services, an Albany-based company vying for the state's red light camera contract. This, by the way, is not the first time that the press has suggested that a piece of Gantt's legislation is a "contract bill" favoring Gaddy and CMA.

To further twist this tale, a staffer in Gantt's Rochester office said that Gantt has never supported any type of traffic enforcement cameras. The staffer said that, although he could not speak for the Assembly member, there is a "slippery slope of automation" and that cameras "might make a mistake," issuing a ticket for a necessary violation and unjustly punishing a driver.

When asked why Gantt would bother to introduce a camera enforcement bill, the staffer responded that, "it was to control the legislation -- to do what he wants with it."

Where are We Now?

Whatever Gantt's reasons for opposing the legislation, it's quite clear that, for now, New York City won't see bus lane enforcement cameras operating along the first Select Bus Service route. For supporters of the plan, this is a heavy blow.

"Without bus lane enforcement cameras Select Bus Service will be good, but by no means as great as it could be," said Norvell. "Perhaps this will make the DOT look at other ways of ensuring the integrity of bus lanes and speeding bus commutes, like physically separated lanes that don't need to be OK'd by Albany"

Others have suggested more radical remedies. Comments on the progressive urban planning Website Streetsblog called for New York City's succession. One individual, writing under the moniker Urbanis, wrote, "I'm outraged. Once again another livable streets initiative for New York City has been stymied because of our corrupt and dysfunctional state legislature in Albany. I feel all transit riders here have been collectively slapped in the face. New York City has been deprived of home rule on so many fronts, ranging from rent regulation to congestion pricing to bus lane enforcement. It's time for us to secede."

Assemblyman Jonathan Bing, who introduced the legislation, gave the New York Times a more measured comment in a similar vein: "This is such a specific New York City issue, it's one of the many things where you wonder why the State Legislature has any role in it at all."

Graham T. Beck is the managing editor of Transportation Alternatives' StreetBeat, and a freelance writer. He lives in Brooklyn. Â

Bridging Mass Transit's Budget Gap

In 1982, Richard Ravitch, then chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, cobbled together $8.5 billion in city, state and federal financing to fund an MTA Capital Plan that helped turn the troubled system around.

On April 8, Gov. David Paterson announced that Ravitch would have the rare opportunity to try his hand again. This time, Ravitch will not be serving in an official MTA capacity but as the head of a blue ribbon panel of business, civic leaders and economists charged by the governor with recommending ways to patch the $17.5 billion hole in the MTA's $29 billion Capital Plan.

When the New York Sun asked Ravitch about his appointment, he said, "I am not sure it is anything but a Sisyphean task, but I will undertake it with energy and enthusiasm," an appropriate response considering that he has pushed the MTA's budget boulder uphill before, and today it's low on the slope once again.

The Capital Plan

The MTA's 2008- 2013 Capital Plan was released in late February, 18 months ahead of schedule, in accordance with the deal that formed the New York City Traffic Congestion Mitigation Commission, the panel that recommended congestion pricing. Many of its specifics, including use of revenues from congestion pricing, are now moot because of the state legislature's failure to approve the plan to charge people to drive in Manhattan. The capital plan, though, still stands as a fairly accurate predictor of the MTA's financial needs for system maintenance, improvement programs, completion of current expansion projects and expansion to provide new capacity.

The Capital Plan consists of three funding tiers. The first tier, the Core Program, allocates just over $20 billion to address the agency's core needs including bringing the systems to a state of good repair, normal replacement and system improvement. The vast majority of tier 1 funding, about $15 billion, would go to NYC Transit, with around $2.6 billion going to the Long Island Rail Road, $1.8 billion to Metro North, and $400 million to MTA buses.

The second tier allocates $5.5 billion for existing expansion projects like phase one of Second Avenue Subway construction, the Fulton Street Transit Center, the South Ferry Terminal and regional investments that would maximize the benefits of expansion projects.

The third tier focuses on new expansion projects, allocating $3.2 billion for computer-based train control and more cars on the 7 Line, Penn Station Access, phase 2 Second Avenue Subway construction and Jamaica Station improvements.

Meanwhile, rising construction costs have opened up a $3 billion gap in the 2005-2009 Capital Plan.

The MTA's financial situation extends beyond construction and equipment budgets, however. An analysis of the July four-year Financial Plan by New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli shows several items straining the budget. These include the debt service on bonds issued during the Pataki administration to finance past Capital Plans as well as the rising costs of healthcare and pensions, and the economic downturn. DiNapoli's report predicted that the operating budget deficit will grow from $965 million in 2008 to $2.1 billion by 2011.

Paying the Bill

To cover all these costs, the MTA has four potential funding sources: fares from subway, bus and commuter-rail riders; city, state and federal government contributions; an increase in existing taxes dedicated to transit, like the mortgage recording tax; and new revenue streams slated for transit, such as congestion pricing.

An increase in all four of these sources will almost certainly be needed if the MTA wishes to maintain the level of service, reliability, cleanliness and safety that 8.5 million daily riders have grown accustomed to and if the agency hopes to expand and improve the system.

The agency will almost certainly, however, have to raise fares more sharply than it did a few months ago if it hopes to keep up with the rate of inflation and balance the operating budget. DiNapoli, in his analysis, reported that the MTA has proposed another 5 percent fare increase for January 1, 2010. That said, it is very unlikely that the MTA will look to fare increases or fare backed-bonds to fund the Capital Plan.

Increased support from the city, state and federal government is always on the MTA's agenda. Former Gov. Eliot Spitzer had made it clear that he planned to fully fund the MTA's Capital Plan, although he never offered details on how he would do that. Paterson has been less explicit, though there are rumors in advocacy circles that another transportation bond act may be in the state's future.

On the federal level, in his State of the MTA Address, Sander pointed out that China spends 9 percent of its gross domestic product on infrastructure, while India aims to boost its spending from 3.5 percent to 8 percent in the coming years. The United States spends less than 1 percent of its GDP on infrastructure.

"Even after Albany and City Hall resume making significant contributions to the MTA Capital Program, it still won't be enough," Sander said, "We must join other national transit providers to persuade Washington to pitch in and provide a much higher level of federal support."

Increasing transit-dedicated taxes and fees will certainly be a big part of the equation. The economic slowdown, though, makes this a daunting task. The MTA will require increases in several transit-dedicated taxes and fees like the mortgage recording tax, the petroleum business tax and vehicle and license registration fees, to simply compensate for money lost, let alone to generate billions of more dollars.

Looking for Money

The heart of any Capital Plan funding strategy, then, in large part may be focused on identifying new transit-dedicated revenue streams. A 2004 report by the Regional Plan Association titled "Financing Options for the MTA Capital Program" looks at possible sources of revenue. It considers a few possibilities

--Traffic pricing, such as the congestion pricing plan: With the State Assembly having refused to even vote on Mayor Michael Bloomberg's proposal to charge a fee to drive in Manhattan during the work week, this seems off the table for the time being. However, according to Marc Shaw, former chair of the Traffic Mitigation Commission, Ravitch has not taken the option off the table.

--A gas tax: As gasoline prices have risen, some politicians, notably presidential candidates John McCain and Hillary Clinton, have called for doing away with the gas tax. Raising it in the current political climate appears unlikely.

--A commuter or payroll tax: The commuter tax, which raised $325 million the last full year it was collected, has popped its unpopular head out of the water repeatedly since it was drowned in 1999 by Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver. Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Kathryn Wylde of the Partnership for New York City, the Queens Civic Congress and others have at various times all floated the idea, but the general consensus is that the commuter tax is a non-starter in Albany.

Acknowledging this, the Regional Plan Association report suggests that the commuter tax could be refashioned into a mobility fee or payroll tax that draws on more earners and employers and is openly dedicated to transit. Based on 2000 income data, a 1 percent tax on wages after the first $50,000 could generate $820 million annually.

Looking Ahead

Tough times for the MTA mean tough times for the city and tough times necessitate tough measures. That could mean anything from service cuts to further construction delays to double-digit fare hikes to layoffs.

For now, we'll have to wait and see what revenue-generating proposals Ravitch's Commission recommends, what the 2009-2014 Capital Plan looks like and whether the economy warms, cools or stays where it is.

Despite the tough times, seasoned transit advocates are hopeful. "I'd be deeply depressed if we hadn't managed" to fund the capitol plan since 1982 said Gene Russianoff of the Straphangers Campaign. "If there is anyone who can find the funds needed to keep fixing transit now, it's Ravitch."

Graham T. Beck is the managing editor of Transportation Alternatives' StreetBeat, and a freelance writer. He lives in Brooklyn. Â

Bridging New York's Transit Gap

large cities such as Taipei and Bogotá.

While U.S. cities such as San Diego and Las Vegas have recently rolled out bus rapid transit, New York can learn more from the experiences of cities in the developing world cities, such as Curitiba, Brazil, and Bogotá, Colombia. Like the emerging megacities of the south, New York urgently needs better transportation for a dense population that already embraces mass transit - and a solution that can be implemented quickly and cost-effectively.

In other US cities, transportation wonks debate whether bus rapid transit, or BRT, a series of measures to move buses faster and reduce waits, can make buses sufficiently attractive to attract upscale riders and/or spur transit-oriented development. In much of the country, what transit there is consists of conventional bus systems that are underfunded, often ill-managed and, as a result, used only by people too poor, too old or too disabled to drive. Planners trying to popularize transit in car-dominated cities fret over whether BRT has enough cachet to overcome the stigma attached to buses and the people who ride them.

In New York, though, our challenge isn't attracting enough riders to make transit viable - it's providing enough transit to handle what is already an overflow customer base, not to mention the million new riders that PlaNYC anticipates. The epic saga of the Second Avenue subway illustrates a hard truth - building new subway lines in New York City is too slow and costly to address a meaningful share of our need.

Even if money were no problem, few of the major rail projects on the boards would do much to make our commutes faster or less crowded. The extension of the Number 7 train extension is typical - it's about enabling development on the far West Side, not about improving the lives of the people packed onto that train today.

Transit-starved in a Transit-rich City

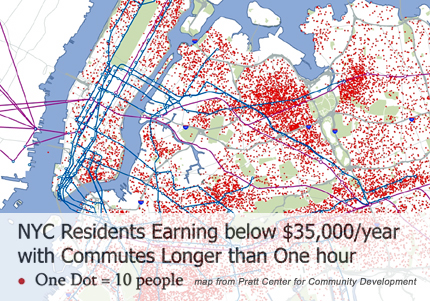

Meanwhile, three quarters of a million New Yorkers now travel over an hour each way to work. Two thirds of these commuters are on their way to jobs that pay less than $35,000 per year. These are folks who live at the far ends of subway lines or in places the subway doesn't go, or who commute to places the subway doesn't connect them to.

Rising housing costs have forced many low- and moderate-income people out of neighborhoods with good access to transit - such as Harlem, Williamsburg, Jackson Heights, to name a few -- to places like Soundview, East Flatbush, East Elmhurst and many others from which it's a bus ride or maybe two bus rides to the closest subway.

Another factor is where the jobs are. While jobs in the financial and creative sectors are concentrated in Manhattan, low- and moderate-wage employment in services, the trades and manufacturing is dispersed across the city. Most New Yorkers work in the same borough they live in, but unless that borough is Manhattan, this translates into long transit trips to work. An intra-borough trip that might take 20 minutes by car can take 45 minutes or more by bus because buses are slow and connections are poor.

As a result, poor transit access restricts economic opportunity. Workers with less than a college degree already struggle to find a limited universe of jobs that are a match for their skills; that universe is further reduced when they consider only jobs within a manageable commute from transit-poor neighborhoods. And opportunities for advancement through education are likely to be confined to the unaccredited colleges and trade schools that cluster around outer-borough transit hubs.

Long commutes also undermine family and community life. Low-wage workers seldom have the flexibility that allows higher-earning parents to juggle school and community meetings, get kids to after-school activities, doctor visits, etc., and handle the inevitable emergencies. When workplaces are an hour away from home, school and childcare, it's hard to find time for more than the most basic parenting tasks.

Many of New York's public housing developments are transit-deprived. Robert Moses, in particular, tended to build projects in isolated areas where land was cheap and local opposition was minimal. The Master Builder may not have cared whether his tenants had access to jobs, education, and services -- so to this day, tens of thousands of public housing residents remain stranded far from the nearest subway line.

BRT and Neighborhoods

As Phase 1 of the Second Avenue Subway inches toward completion, nobody in Morrisania, Canarsie or South Jamaica is holding their breaths waiting for the train to come in. But bus rapid transit -- "a subway running above the ground on rubber tires" could be in place relatively quickly and cheaply. Full BRT - with protected lanes, traffic signal prioritization and off-board fare payment - can move people at speeds and volumes that dramatically shorten travel times over long routes. Moreover, BRT will be accessible from its inception - to wheelchair users, seniors and everybody who has trouble climbing stairs - while the goal of providing access at every subway stop is still many years away. BRT will create an efficient no-transfer option for hundreds of thousands of people whose mobility is now limited to the radius a conventional bus can cover at a speed of 7.9 miles per hour.

Though dedicating lanes to buses presents a political challenge, BRT complements plans to reduce car use by making more efficient use of street space. There are a number of ways to ensure that the lanes are used by buses and buses alone. The lanes can be physically protected, but license plate cameras on the buses themselves are a more elegant solution -- letting the buses themselves nab the drivers who infringe on their space. However, enforcement cameras face an uncertain fate in the state legislature, where Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver has thus far resisted pressure to authorize additional red-light cameras in the city.

The City's First Steps

On March 25, Mayor Michel Bloomberg presided over the joint announcement of New York's first BRT route by Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan and Lee Sander, executive director of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Dubbed "Select Bus Service," it will replace limited-stop Bx12 service on Fordham Road/Pelham Parkway in the Bronx starting June 29. Most of the key BRT features are part of the package including off-board fare payment. Machines at bus stops will accept MetroCards or cash in exchange for a paper receipt. Following the example of many European transit systems, riders will be subject to random checks - but passengers will be able to board through front and rear doors, eliminating the bottleneck that forms as each rider swipes at the front door.

BRT-specific vehicles - low-floor buses with multiple doors - are still in the future, but the willingness of the transportation department and MTA to try "honor system" payment, as well as the department's painstaking work with local stakeholders to resolve conflicts around truck unloading and parking, signals a will to make this first route work. The more successful the initial BRT project is, Sadik-Khan reasons, the more communities will clamor for BRT to come to them as well.

Transit Funding without Congestion Pricing

Now that the state has failed to act on congestion pricing, when BRT will roll in the other boroughs is anybody's guess. The federal Urban Partnership grant that New York forfeited when the State Assembly did not vote on congestion pricing earlier this month would have funded a five-route pilot project, adding one BRT route each in Staten Island and Brooklyn, and two in Manhattan. (Resistance to the removal of some parking along Merrick Boulevard was so fierce that plans for a Queens route were put on hold, and a 34th Street crosstown route advanced in its place.) Of the $354 million in federal funds, $112 million would have paid for BRT.

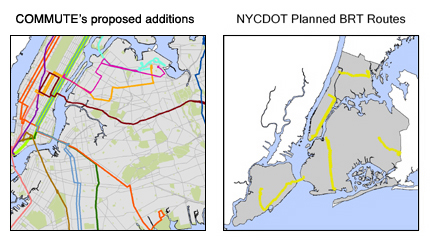

Meanwhile, a small but growing number of transit advocates and riders who know what BRT is are clamoring for more routes. COMMUTE! (Communities United for Transportation Equity), a coalition of community groups coordinated by the Pratt Center for Community Development, wants the BRT routes to cross bridges and connect the boroughs, making buses a more serious complement to the subway system.

The pilot program confined each route to its respective borough, so that the Rogers Avenue/Nostrand Avenue route in Brooklyn would serve a dense and underserved slice of East Flatbush, Crown Heights and Bushwick - but then dump passengers at Williamsburg Bridge plaza, presumably to elbow their way onto already full J, M and Z trains to get into Manhattan. Since the transportation department is already planning to put a dedicated bus lane on the Williamsburg Bridge, it would be logical to connect the Brooklyn BRT route to the also-planned First/Second Avenue BRT.

With both the one-time shot of federal funding and the projected $500 million per year in net revenues from congestion pricing off the table for the moment, BRT may be more important than ever. The MTA Capital Plan has, in words of Straphangers Campaign spokesman Gene Russianoff, "more hole than plan," with less than $12 billion of a five-year, $29 billion shopping list accounted for. As the rail and subway projects envisioned in that plan recede into the future, BRT makes more sense than ever. It will not prevent us from building light rail or subways in the future, but for now it makes intelligent use of the infrastructure we already have - our streets.

Joan Byron is the director of the Sustainability and Environmental Justice Initiative at the Pratt Center for Community Development.Â