New Bills: Biking On The Boss's Dollar

At its stated meeting September 25, several council members introduced legislation that makes a business liable when their delivery workers or bike messengers violate traffic regulations. Legislation was also introduced to allow advertising on sheds surrounding scaffolding.

Fining Bicyclists' Bosses

Councilmember Jessica Lappin received a letter from 9-year-old Annabel Azziz of the Upper East Side, saying she worried about bicyclists who violate traffic regulations. "Now we cannot take a simple walk without being nervous of bicycles zooming next to us in the park," Annabel wrote of her strolls with her father in Central Park.

The councilmember decided it was time for someone to pay. Not the bicyclist, Lappin said, but his or her employer.

Lappin introduced legislation (Intro 624) with Councilmember Alan Gerson that shifts the burden of traffic fines from the bicyclist to the bicyclist's employer. The move, Lappin said at a recent press conference on the City Hall steps, will encourage employers to train their messengers and delivery personnel and keep pedestrians safe on the city's sidewalks.

"For children and seniors, getting hit by a bicycle can be life threatening," said Lappin – one of her elderly residents was struck by a bike last month and needed hip replacement surgery. "So the message is simple. Businesses have to be held responsible for their bikers."

Currently, a bicyclist can be fined between $100 and $300 for violating traffic rules, and is also subject to an additional $200 fine if the rider hits a pedestrian. In 2006, Lappin said, the New York City Police Department issued approximately 40,000 traffic violations to cyclists. Because bicyclists are required to wear a logo or sign with their place of employment, the violation's transfer will be smooth, she added.

Restaurants and companies will likely comply with the legislation, Lappin added, because she hopes to publicize habitual offenders.

Transportation Alternatives, a nonprofit advocacy group, supports the legislation. "(Employers) should be responsible in seeing that their workers follow these laws and culpable if they do not," the group said in a prepared statement.

Advertising on Scaffolding

Despite efforts by arts associations, the buildings department and Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer to eradicate illegal advertisements on the city's scaffolding, Councilmember Melinda Katz would like to see advertising on sidewalk sheds - the structures that enclose portions of scaffolding.

According to legislation (Intro 623) introduced last month, the commissioner of the Department of Buildings would set a price to lease space to businesses looking to place their ads. The sidewalk shed advertisements would only be permitted in commercial or manufacturing zones and could not abut a building or property located in a historic district or that is designated a landmark site.

Katz, who is a candidate in the 2009 race for city comptroller, said the advertising could boost city revenue. The legislation's critics contend the advertising can be an eyesore, and the removal of scaffolding could be stalled so the owner of the property could continue making a profit.

Retaining Walls

Councilmember Michael McMahon also introduced (Intro 625) legislation that requires the construction of retaining walls be scrutinized more thoroughly.

Currently, retaining walls are included in the Department of Buildings professional certification program, which allows plans submitted by a certified architect or engineer to go through the approval process more swiftly. In this program, the certified professional ensures the plans comply with all applicable city codes, and thus is not subject the same intense examination.

According to the legislation, retaining walls greater than 3 feet would no longer be included in the program, and thus construction would be subject to more scrutiny no matter who submits the plan.

Â

State of Cycling

Even in packed subways, high gasoline costs and concerns about health, less than 1 percent of all New Yorkers regularly use their bicycles to commute to work. At the same time,18 percent of all New York City adults still smoke cigarettes.

Over the past five years, the Bloomberg administration has made a massive and somewhat successful effort to reduce the number of smokers. Now, can the same government that persuaded New Yorkers to stop smoking create an environment that will convince them to start cycling?

More than ten years ago, the Giuliani administration formally introduced the Bicycle Master Plan for New York City, an initiative to develop a city-wide bicycle network to increase ridership and integrate cycling into the city's transportation system. Since then, the plans have evolved. This spring, cycling has emerged as part of PlaNYC 2030, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's ambitious proposal to make New York City more environmentally friendly and reduce carbon emissions believed to cause global warming. The current plan calls for the completion of an 1,800-mile system of bike routes by 2030, as well as improvements to biking facilities and increasing public awareness. But New York still lags behind many other cities when it comes to promoting bicycling, and a number of questions remain about safety, facilities and the fight for always scarce space in the crowded city.

Building The Network

Since Bloomberg announced PlaNYC in April, the city has already begun work on trying to increase bicycling. Some advocates viewed earlier city efforts as sluggish. The city's previous transportation commissioner, Iris Weinshall, was criticized for being uninterested in cycling, and the department's bicycle program director resigned last summer. But advocates have praised Weinshall's successor, Janette Sadik-Khan, who was named commissioner in April, for her commitment to alternative transportation and environmental sustainability.

The administration is already trying to reach the cycling program’s first benchmark -- adding 200 miles of bike lanes by 2009. Overall, PlaNYC calls for:

• 500 miles of separated bike paths

• About 1,300 of miles of striped or marked bicycle lanes

• Additional greenways, or car-free paths that connect the city’s parks.

• Improving public education on cycling and safety issues and observation of traffic laws

• Installing 1,200 additional bike racks by 2009

The city’s move toward a complete bicycle network has not been without debate. A proposed bicycle lane on a car-free block of East 91st Street has drawn opposition from members of the local community who want to preserve the tranquility and safety of the street. The Upper East Side residents of Community Board 8 are also frustrated that city officials did not consult them before deciding on the lanes, according to David Liston, the board's chairman. "On something so serious, so important, and recognizing how important bike lanes are for the city, I don't know why they did not come to us sooner," he said. The community supports the city's efforts to install new lanes and encourage cycling, according to Liston, but he added, East 91st was "simply the worst location" for a bike path.

According to the New York Sun, residents of the Upper East Side have enlisted their elected officials all the way up to their congresswoman. The transportation department is considering an alternate route.

A plan to have bike lanes along Ninth Street in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn encountered opposition from residents hostile to bicyclists and from those who said the lanes would make it more difficult for them to double park in front of their homes to drop someone off. The city approved the lanes anyway.

Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, said the community tension over facilities for bicycling stems from New York’s longstanding focus on cars at the expense of cyclists and pedestrians. “Our city for the past six or seven decades has been designed around cars, which is the most inefficient use of city space to move people around,” he said. “What we’re left with is that bikers and walkers are fighting over the scraps.”_

Bike Sharing

Many New Yorkers cannot take advantage of the city’s lanes and paths because they either do not have a bike – it can be hard to store them in tiny apartments—or find it difficult to transport their bikes around the city. To address that issue, some cities around the world have implemented bike sharing. Advocates want New York to follow their lead.

" I think a look to a city like Paris would really be instructive," said David Haskell, founder of the New York Bike Share Project, referring to the French capital's recent launch of its own bike-share program. Paris currently provides more than 10,000 bikes that can be picked up, ridden and dropped off at another station in the city. Renters swipe a pre-paid subscription card and pay for any time beyond the first 30 minutes. And the city plans to install 10,000 more bikes within a year.

The Paris initiative, the largest in the world, is one of several around Europe that Haskell looks to when envisioning one for New York City. Last month he organized a five-day project in which riders could rent a bike for a free 30 minutes in SoHo and drop it off at another location. The program drew hundreds of people eager to try it out.

Since then, support has continued through e-mails and calls to his office, he said, and he hopes to launch an expanded follow-up project next spring. That program will be temporary, but Haskell called it “a way to keep the public interested,” while the city ultimately considers a permanent system.

Advocates are excited about the idea, and city officials considering whether it could work here. A bike-share program would require hundreds of stations at which to pick up and return the rented cycles. The department would not speculate on what else those stations might include. “Finding the space for all those stations is really something that’s under consideration,” said Joshua Benson, the Department of Transportation's bicycling program coordinator.

A Cycling Infrastructure

A system of shared bikes, though, is just one element in creating an entire infrastructure for cycling in New York. “We’re just seeing what’s out there in other cities,” Benson said. He said a “complete bike network" would include increased bicycle lanes, as well as bike parking and storage.

Budnick of Transportation Alternatives also emphasized the need for bicycle parking and storage -- the lack of safe storage is the number one reason why people in the city don’t take their bikes to work, according to 1999 report by the Department of City Planning. To that end, the transportation department under PlaNYC is continuing its CITYRACKS program -- in which the department builds racks based on requests from throughout the city -- and aims to put up 1,200 more racks in the next two years. The plan also calls for a law that would require commercial buildings to provide bicycle storage.

Budnick of Transportation Alternatives also emphasized the need for bicycle parking and storage -- the lack of safe storage is the number one reason why people in the city don’t take their bikes to work, according to 1999 report by the Department of City Planning. To that end, the transportation department under PlaNYC is continuing its CITYRACKS program -- in which the department builds racks based on requests from throughout the city -- and aims to put up 1,200 more racks in the next two years. The plan also calls for a law that would require commercial buildings to provide bicycle storage.

Safety

One challenge to increasing bicycle rider ship in the city is making it safer. A 2006 city study found that from 1996 to 2005, 225 cyclists died in crashes, 92 percent of them in accidents involving cars. Also, several high profile deaths in the past year, two from car crashes on a popular Hudson River bike path, have further highlighted the need to protect cyclists. One motorist, who killed a cyclist, drove along the bike lane, apparently not realizing it was not intended for motor traffic. Flexible plastic pylons are all that separate the Hudson River from motor traffic, prompting transportation officials to consider a switch to bollards, or steel posts or other barriers that are cemented to the ground.

A study released by Transportation Alternatives earlier this month found that 52 percent of cyclists surveyed felt “very safe” or “safe” in buffered lanes, in which there is an additional five-foot-wide painted space between the bike lane and auto traffic. Meanwhile, the study found, only 21 percent felt secure in conventional bike lanes, which offer no barriers between cyclists and drivers.

The study concluded that the city should come up with “more innovative ways” to protect bicyclists from car traffic as it adds bike lanes to major routes. “I think the next step in making the city’s bike network stronger is the city putting in actual protected bike lanes on the street,” Budnick said. He suggested that bollards be used to physically separate bike lanes from motor traffic.

The transportation department has recently begun to paint some bicycle lanes throughout the city bright green in order to make them more visible to car and truck drivers. Although many residents find the color ugly, the city plans to paint about five miles of these lanes in areas where drivers are more likely to clash with cyclists.

The city’s other current safety efforts include a free helmet giveaway and a recent law to protect bicycle delivery workers. Benson, the city’s bicycle program coordinator, also said an ad campaign would be launched in September that would “highlight the rights and responsibilities of motorists and cyclists.”

Haskell said the city deserves a lot of credit for its work with bicycles in the last two years. “There’s definitely been a shift in the understanding of how bikes can conquer the larger transportation challenges in the city,” he said. But, Haskell added, the administration still has work to do. “I would still urge the city to be a bit more bold with their thinking and a bit more visionary in terms of the scale of what might be done,” he said.Â

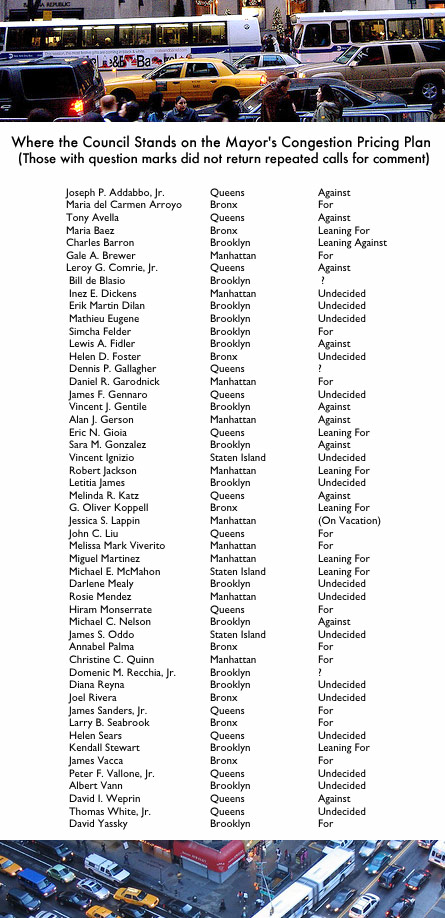

A Divided Council Confronts Congestion Pricing

In the touch and go, back and forth, here and there negotiations over Mayor Michael Bloomberg's congestion pricing plan, a new player got caught up in the controversy: the City Council.

If the mayor receives enough federal funding to move his plan forward and if it then receives the blessing of a 17-member commission, 51 council members will have to decide where they stand on charging cars $8 and trucks $21 to drive into or out of Manhattan below 86th Street during the workday.

Most council members are not yet ready to make that decision. But over the next several months, they could face a divisive issue, featuring the kind of democratic and sharp debate not really seen in council since the 2005 controversy over the city's waste management plan.

The Breakdown

Of the 47 City Council members who responded to Gotham Gazette’s query, only 23 council members took definite positions on the mayor's proposal. The others are leaning one way or the other or say they are undecided.

Twenty council members support or lean toward the plan. Another 11 oppose it or lean against it. Nearly a third of the council, or 16 members, contacted by Gotham Gazette said they were undecided, and three others did not return repeated phone calls. Jessica Lappin was on vacation and so unavailable.

For the plan to pass, 26 council members would have to approve it. With City Council Speaker Christine Quinn supporting the fees, Bloomberg may be able to move some members over to his side.

The next step for congestion pricing could come as early as this week when the federal government tells the city whether it will receive up to $500 million to purchase equipment to implement congestion pricing and for mass transit improvements, including buses. The plan must then receive a favorable review from a 17-member commission charged with coming up with a plan to reduce the city’s notorious traffic jams, according to the bill approved by the state legislature late last month. If all that happens, then it will be the council’s turn to weigh in. If they approve congestion pricing, the final say will rest with the legislature and the governor.

Who Stands Where on Congestion Pricing

Surprisingly, where the council members’ districts are seem to have little effect on their position. One could assume those from the outer boroughs would be the most likely to oppose the idea. But some of congestion pricing's most outspoken supporters, like Councilmember John Liu, hail from Queens, while others who have expressed doubts, like Councilmember Alan Gerson of lower Manhattan, are from districts that supposedly would reap the most benefits from it.

Many of the council members listed as for or leaning for said their continued support hinged on the city making improvements in mass transit. Bloomberg has promised to do that, using first the federal funds and then the revenues from congestion pricing.

Council Gets Its Say

Congestion pricing has the potential to be that rare thing in City Hall – a divisive issue that could split alliances. As he has repeatedly done, the mayor initially wanted to exclude the City Council from having any role in congestion pricing. But during negotiations over the plan in Albany, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver reportedly insisted that the compromise creating the commission require the council's approval before the legislature could vote on any plan to relieve congestion.

"I've been insisting that the council has an absolute right to weigh in on this," said Councilmember Lewis Fidler – a congestion-pricing foe who introduced a resolution several months ago against the proposal. "Institutionally it's very important for the council that that be done. This is the issue of whether or not tolls are going to be imposed on the streets of New York," not Albany, he added. "I for one feel relieved."

Although the deadline for council to approve or reject the plan put forth by the commission is not until March 31, 2008, Council Speaker Christine Quinn is already gearing up to reach a consensus. Quinn, who will appoint three representatives for the 17-member commission, supports congestion pricing, albeit with conditions.

In a memo sent to council members last week, the speaker stated she would schedule individual meetings with every member to review their complaints, concerns and apprehensions regarding congestion pricing.

The memo states: "While I support congestion pricing, I am keenly aware that many of you have expressed concern about congestion pricing and will have questions about the agreement. I understand that a plan of this magnitude, whether congestion pricing or another method, will profoundly and uniquely affect each of your districts. I am committed to working with each and every one of you to hear and address those issues."

Their Reasons For Support

Council members, like other New Yorkers, recognize traffic is more than an inconvenience here – it creates health problems and affects the city economy. According to the mayor's proposal, congestion costs the city $13 billion in lost business revenue, lost time and increased vehicle costs. With congestion pricing, the report contends, 94,000 commuters would shift from driving to mass transit. A transition of that magnitude would consequently reduce the emissions that cause global warming and better the city's environment.

Council members, like other New Yorkers, recognize traffic is more than an inconvenience here – it creates health problems and affects the city economy. According to the mayor's proposal, congestion costs the city $13 billion in lost business revenue, lost time and increased vehicle costs. With congestion pricing, the report contends, 94,000 commuters would shift from driving to mass transit. A transition of that magnitude would consequently reduce the emissions that cause global warming and better the city's environment.

"Besides alleviating a lot of the pollution that goes into our environment from so many people that drive into work, it will help us improve our transportation system," said Councilmember Annabel Palma, a supporter of the mayor's plan dependent upon certain transportation improvements in her Bronx district. "And again it always helps to be able to put together a plan that will keep people healthier for longer periods of time."

While some council members said congestion pricing unfairly burdens those outside of Manhattan, others see the plan as righting a longstanding inequality from borough to borough. "I lean toward it from the fact it spreads out the burden Staten Islanders have borne," said Councilmember Michael McMahon, referring to the tolls his constituents pay. Under the plan, the tolls will count toward the $8 congestion fee.

Their Reasons For Concerns

Most council members' who oppose or lean against congestion pricing say they worry that the tolls will be implemented without the transportation improvements promised in Bloomberg's PlaNYC 2030 environmental proposal. These include five bus rapid transit routes in each borough, allowing buses to travel in special designated lanes, and increased capacity on the city's most traveled subway lines. Even those who have endorsed the mayor's pricing proposal, like council members Simcha Felder, Palma and Quinn, have said their support depends on these other promised improvements.

"I don’t believe we've exhausted every alternative before charging residents to drive into the city," said Queens Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, an outspoken critic of congestion pricing. "We could enforce cars (to stay out of) bus lanes. We could enforce other traffic rules. We could look at delivery hours."

A short list of other complaints include:

--fears that outer-borough neighborhoods would become parking lots for commuters wanting to leave their cars outside the congestion zone;

--concerns that congestion will increase outside the zone. This would raise emissions in some neighborhoods and increase health problems, like asthma, there;

--a belief that the $8 toll equates to a regressive, commuter tax that is unfair to the poor.

"I think the plan is myopic and shortsighted and does not show the real depth and purpose in creating the types of resolutions that would benefit the entire city of New York," said Councilmember Leroy Comrie.

The Undecided

The many council members who have not made up their minds raise an array of issues including whether commuters will use parking places, crowding out neighborhood residents, and what effect hundreds of cameras photographing drivers going into, within or out of the zone could have on the privacy and security of New Yorkers.

"What about above 86th Street?" asked Councilmember Thomas White of Queens. "What about the other boroughs? On face value, I'm not satisfied."

Other members representing districts outside the zone, like Maria Baez and James Sanders, worry about plan's effect on the poor. Both suggested incorporating a tax rebate for those charged by congestion pricing.

The undecided are united on one thing: Their main concern remains getting their constituents to their destinations in the fastest, easiest and cheapest way possible.

"What I fear is mass transit won't be prepared for it," said Councilmember Joel Rivera, who also questions the impact of a looming fare increase by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Rivera, though, is still open to the concept. "As a person that drives into the city… it gets congested."

Some are simply holding off on pledging support or opposition because the final details have not been determined. "The proof is in the pudding, and the pudding isn't even in the oven," said Councilmember Robert Jackson.

In fact, the council might never get to vote on congestion pricing. The commission, comprised of members appointed by the mayor, City Council speaker, governor, State Senate majority leader, Assembly speaker and minority leaders of both houses, would meet over the next several months. The plan it recommends does not have to resemble the mayor's. Its only criteria would be to reduce congestion by as much as Bloomberg's proposal – 6.3 percent.

Whatever comes out of this, many officials expressed optimism that in several years New York City will be healthier, greener and less congested. "It's going to be definitely different," said Councilmember Gale Brewer, a pricing supporter, discussing the so-called inevitable revisions to Bloomberg's plan. "If there is real mass transit plans, if we really have a discussion about high quality mass transit that happens with the $500 million, then I think people would be interested."

Â