Urban Issues: Mass Transit

• • • • • • •

John Edwards

Edwards supports federal mass transit initiatives like the Federal Transit Administration's Job Access and Reverse Commute program, that helps low income people who do not have cars get to jobs in the suburbs.

John Kerry

Kerry supports giving cities options on how they spend federal transportation money, including projects for light rail, streetcars, and redesigning streets and sidewalks.

Dennis Kucinich

Kucinich calls for federal financing of $50 billion in zero-interest loans every year for ten years. State and local governments could use the money to build roads and mass transit. States would have to repay the principal, but these bonds would pay zero interest. The plan would cut infrastructure improvement costs in half.

Al Sharpton

Sharpton advocates spending $50 billion a year over five years on highways, railways, and infrastructure.

George W. Bush

In 2002, President Bush guaranteed an increase in the Department of Transportation funding level with $6.7 billion, $486 million earmarked for expansion projects in mass transit. The Bush administration provided Amtrak with $521 million to continue operating.

In December 2003, the Department of Transportation announced $2.85 billion in grants to build a new PATH terminal, connect 12 subway lines in a new Fulton Street subway station, and replace the South Ferry subway terminal in lower Manhattan.

• • • • • • •

Back to Urban Issues Main Page

• • • • • • •

GOTHAM GAZETTE’S RELATED ARTICLES

• Urban Agenda: Mass Transit

• How New Yorkers Get to Work

• New Subway Projects and their Benefits

• Same Projects, No New Money

• Debating Transportation in Lower Manhattan

• Permanent PATH Station

How New Yorkers Get To Work

Debates about transportation often focus on big construction projects such as the Second Avenue subway, the extension of the #7 subway line and a new transit center on Fulton Street in lower Manhattan. One might think from this that the only means of transportation in New York is the subway to Manhattan. But, according to recently released data from the 2000 census, less than a third of New Yorkers take the subway to work in Manhattan.

Of the 3.7 million people who work in the five boroughs of New York City, 2.1 million work in Manhattan. (That's 56 percent. The other 44 percent work in the other four boroughs). Of the 2.1 million who work in Manhattan, 1.2 million take the subway or a commuter railroad to get to work.

The homes of these 1.2 million workers are not spread evenly throughout the city. As Map 1 below shows, commuting to Manhattan by subway is more prevalent among workers who live on the Manhattan's west side above 59 Street, in lower Manhattan west of Broadway, and in certain neighborhoods in western Queens and western Brooklyn.

Of those taking other forms of transportation to work in Manhattan, 53,000 regularly take a taxi, 163,000 walk to work, and 245,000 take the bus.

Another 360,000 people drive to their Manhattan jobs. Map 2 shows, not surprisingly, that auto commuters live disproportionately in the outer parts of the Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island in areas with poor transit access to Manhattan and/or very long transit commutes. Even in these areas, however, no more than 15 percent of workers drive to Manhattan.

In sum, the Manhattan jobs powerhouse plays a huge role in the lives of residents of Manhattan as well as those of Astoria, Sunnyside, Forest Hills, Brooklyn Heights, Red Hook and Park Slope. The arc of neighborhoods from Forest Hills in Queens to Park Slope in Brooklyn might be thought of as part of Metropolitan Manhattan, providing relatively high-paying jobs as well as shopping and entertainment to residents of these areas.

As to the rest of the city, there are two basic commuter profiles. The first group is commuters who take transit (subway or bus) to non-Manhattan jobs. Map 3 shows that this group is concentrated in central Brooklyn and parts of the Bronx. One-third to 40 percent of commuters living in these areas take transit to non-Manhattan jobs, most of which are in their home borough.

The final group is comprised of workers who drive to non-Manhattan jobs. In eastern Queens, the northeast section of the Bronx and southeastern Brooklyn, auto commuters going to non-Manhattan jobs constitute 40 percent or more of workers living in these areas. These workers are the least like the typical New York commuter since they do not work in Manhattan and drive instead of taking transit. In this respect, these workers fit the national profile of commuters more than the New York profile.

Amid the diversity of New York, then, three main commuter profiles are evident:

- The subway commuter to Manhattan;

- The subway/bus commuter to outer-borough jobs (mostly in workers' home borough); and

- The auto commuter to outer-borough (and sometimes suburban) jobs.

The first group is concentrated in or near the Manhattan core, the second group in the neighborhoods somewhat further from Manhattan, and the third group in the outermost parts of the outer boroughs.

What does this profile mean for thinking about transportation improvements? First and perhaps most obviously, it raises the question of what type of transit improvements would serve non-Manhattan subway, bus and auto commuters.

Second, these data point to areas that transit may help to continue to transform New York even without any new subway construction. One such area is along the L and M lines in Williamsburg, Greenpoint and along the Brooklyn/Queens border. Only one-quarter to one-third of workers living in these areas take the subway to work. These areas are already becoming more attractive to Manhattan professionals who may be priced out of housing in Manhattan. The once-dowdy L train has acquired some cachet. This trend is likely to continue.

Thus, not only subway lines that might be built, but lines built long ago but currently underutilized, will shape New York's urban landscape.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Taxis

Â

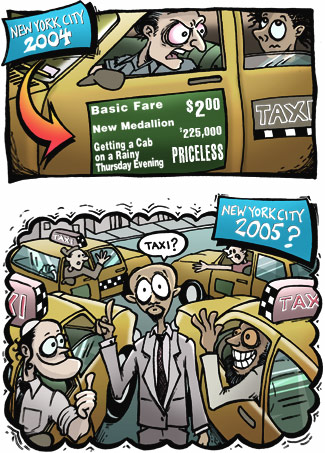

Next time you're standing on a corner in rush hour, muttering in frustration because you can't get a taxi, consider this:

Next time you're standing on a corner in rush hour, muttering in frustration because you can't get a taxi, consider this:

In 1937, when Fiorello LaGuardia was mayor and a youngster named Joe DiMaggio was the toast of the town, 13,566 licensed taxis patrolled the streets of New York.

Today, LaGuardia is an airport, Joltin' Joe's name is affixed to the West Side Highway and there are just 12,187 medallion cabs in the city, a decrease of 1,379. And on a rainy night, it seems like every single one of them is occupied.

The taxi is a vital component of New York's transportation system and a part of the city's history, culture and identity. Yellow cabs carried 240 million passengers in 2002 -- more than 50,000 New Yorkers use taxis as their primary means of getting to work every day (not counting commuters who take cabs from the railroad terminals) -- and they cover some 800 million miles of asphalt each year. Yet cabs and their drivers, among the most regulated of the city's institutions, are also a frequent source of confusion and aggravation.

Now, the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission is proposing a major overhaul of the taxi system, making some of the most visible changes since the city ordered all medallion cabs painted yellow in 1967.

Chief among these is a plan to add 900 taxis over the next three years, the largest increase in almost seven decades. Because taxi medallions currently sell for more than $200,000, the city, which would issue 300 of them in each of the next three years, expects to gain about $190 million, a third of which is already included in this year's budget.

With the increase in the number of cabs would come a fare hike expected to be roughly 25 percent.

Together, these moves are touted as a way of making additional cabs available, easing a shortage that often leaves riders stranded in rush hours and inclement weather, and raising pay for drivers who have not seen the fare increase since 1996.

But not everyone is eager to see these changes.

Additional taxis on the streets will create more pollution and more traffic congestion. Some drivers and owners also worry that more cabs will mean more competition, less pay, and a decline in the value of taxi medallions. And New Yorkers, who are already weary from increased taxes and rising subway and bus fares, are not happy to endure another hike.

"I think that in this economy, when people aren't prospering, it's a lousy time to introduce a fare increase," said Angela Dirks, an architect who takes a taxi at least once a day.

CHECKERED PAST

New York first regulated taxi fares in 1913, fixing the cost of a ride at 50 cents a mile. The Great Depression brought a huge influx of drivers as the unemployed sought to make a buck any way they could, and the explosion in the number of taxis depressed wages and sparked tensions between large fleets and independent owner-drivers. The system grew rife with corruption and labor strife, including a 1934 taxi strike that was the subject of the first play by Clifford Odets, "Waiting for Lefty" (starring future film director Elia Kazan), which became a smash hit, the audience joining in with the actors at the end as they chanted "Strike! Strike! Strike!"

In 1937, LaGuardia attempted to bring order to the chaos by issuing licenses - the first medallions -- for ten dollars apiece. Although the medallions ended the free-for-all that existed for much of the 1930s, they severely limited access to the industry.

As a result of their scarcity, the medallions skyrocketed in value. Owners, seeking to protect their investments, successfully campaigned to prevent the city from issuing new medallions. Due to attrition, the number of medallions actually shrank.

Proposals by the Lindsay, Koch and Dinkins administrations to raise the limit on medallions were soundly defeated. It was not until 1994, under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, that city was able to add another 400 yellow taxis.

The high price of medallions led to the two-tier taxi system that the city now has. Medallion cabs began to focus on the central business districts and the airports because that was the only way to generate enough revenue to justify the high price of a license, leaving the rest of the city to car services or so-called "gypsy" cabs.

Meanwhile, buying and selling the valuable medallions has become an industry of its own, with brokers, consultants and lenders who specialize in financing such purchases.

Medallion Financial Corp., a publicly traded company that, as its name implies, finances medallion purchases (its Nasdaq ticker symbol is TAXI), boasted in a press release just last week that over the past 70 years, taxi medallion prices have risen over 13 percent per year, outperforming the stock market for the same period.

That big rise in medallion prices, particularly in the last 20 years, has also brought about a sea change in the way the taxi industry is structured.

A CHANGING INDUSTRY

For decades, medallion owners operated large fleets of cabs and hired salaried drivers - think of Alex, Elaine, Iggy and the other drivers for the Sunshine Cab Company on the TV series Taxi.

By the time "Taxi" went off the air in the early 1980s, however, such arrangements were already becoming a thing of the past.

Medallion holders got out of the operations business and started charging drivers a fee to use their cars for a 12-hour shift. Around the same time, increased immigration brought an influx of drivers lured by the low barriers to entering this line of work. Pay went down even as the fees drivers had to pay for cabs rose to as much as $100 per day.

It was around this time that the image of the cabbie as a raconteur and crusty but endearing veteran of the streets gave way in the public mind to that of an immigrant who drove recklessly and knew little about the city. (That is, when the public was not picturing a deranged Travis Bickle, as played by Robert DeNiro in the 1976 movie "Taxi Driver".) In response, the city made an effort to educate cabbies and require that they speak English.

September 11 and the ensuing recession made things worse for cabbies, cutting into ridership for the first time in decades. A study released in September 2003 by the Taxi Workers Alliance, which represents 4,800 of the city's 40,000 drivers, said that some drivers took home as little as $22 per shift after expenses and 62 percent were behind on their rent and bills.

Taxi industry officials disputed the precise figures in the survey, but there is general agreement that rising costs have been hurting drivers since the last fare increase almost eight years ago.

SELLING MEDALLIONS - MORE CABS VS. MORE TRAFFIC AND POLLUTION

The sale of 900 medallions proposed by the city would be the largest since the LaGuardia years.

Bruce Schaller, a former Taxi and Limousine Commission official who runs a consulting firm that focuses on the taxi industry, has written about the problems in the taxi industry in his Transportation topic page on Gotham Gazette. He believes that the proposed sale of medallions would result in a noticeable improvement in taxi service.

"I think more cabs are needed to serve the longtime growing demand for service and the industry," Schaller said.

Although 900 cabs over three years does not sound like a lot of additional vehicles, the majority of them will be concentrated in Manhattan below 96th Street, the most congested part of the city.

To critics of the plan, including several environmental groups, that is exactly the problem. Most of these cabs will be in motion throughout the day, adding substantially to the number of vehicle miles on the city's streets. Also, because taxis travel an average of 64,000 miles per year, they are responsible for far more emissions than private automobiles.

"If you make it easier to take a cab people will go from public transportation to taxis." said Noah Budnick of Transportation Alternatives, an organization that promotes bicycling, walking and public transportation. "It's not like you're replacing a car trip with a taxi trip."

The Taxi and Limousine Commission's environmental statement, prepared by the engineering firm Urbitran Associates, concludes that the city can accommodate the extra taxis if it changes the timing of many traffic lights so that they show green for an extra second during each cycle.

The study also maintains that the extra pollution will not be a problem because the city has dramatically improved its air quality in recent years. And it insists that there will be no significant impact on noise in the city because the additional cabs will be operating on different shifts and would be spread out across a large area of the city.

MORE CABS EQUAL MORE COMPETITION

However, some taxi drivers believe there is no justification for additional cabs. They worry that more cabs will mean more competition, less pay, and a decline in the value of taxi medallions. To them, the city is merely trying to grab revenue.

"The city wants to raise money without raising taxes," Bhairavi Desai, the director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, told The New York Times recently. "But the mayor shouldn't balance his budget on the backs of taxi drivers, who work 70 hours a week."

Many argue that a fare hike must accompany an increase in the sale of medallions.

"We do believe that there needs to be a fare increase for current medallions to retain their value and in order for new medallions to bring in the amount the city expects," said Michael Woloz, of the Metropolitan Taxi Board of Trade, a group that represents about 20 percent of the industry. "It's a good investment but only if the owner of the medallion and the driver of that cab can make a good a living."

FARE HIKE - BETTER PAY VS. RIDER BACKLASH

The base fare for a cab ride is $2, and each additional one-fifth of a mile costs 30 cents. Between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m., a night surcharge of 50 cents is added.

In recent months, drivers have threatened to strike if the fare is not increased. Officials are currently proposing a 25 percent hike.

Several drivers testified before the Taxi and Limousine Commission last week that there is a shortage of cabbies because the pay is so low. As a result, many taxis never even make it out of the garage. Supporters of a fare hike say it will go a long way toward making things more equitable for drivers and offset the effects of additional medallions by making each cab more profitable.

But taxi industry representatives also claim that everyone, even riders, will benefit if the fare is raised.

"We believe that if a fare increase is approved that people will invest in the industry and get more cabs on the street to serve the riding public," said Woloz.

David Pollack, executive director of the Committee for Taxi Safety and editor of the Taxi Insider newsletter, agrees it's time the city stopped playing politics with the taxi fare.

"It's been a hot potato," said Pollack, who is also a part-time cab driver. "We would like to see a review every two years so the public doesn't have to get hit with a big increase. Three, four or five percent every two years doesn't hurt as much as 20 percent in one shot."

But if taxi fares increase, some fear a backlash from the public.

A fare increase typically means that more people choose to take public transit or walk. Also with ridership already down, a recent article in City Journal questioned the rationale of raising fares now.

"As the businessman-mayor will remember from Econ 101, you don't respond to sagging demand by raising prices," wrote Howard Husock. "You will only chase more customers away, so that every dollar you gain in higher fares will be lost by decreased ridership."

Even some drivers caution that they may not get to keep the increase; leasing companies, they say, could raise their fees, leaving drivers with little in the way of extra income. Several drivers, speaking on January 7 at the Taxi and Limousine Commission hearing, said the plan would squeeze drivers' incomes while offering riders false hope.

While Pollack of Taxi Insider supports the 900 more cabs as a good start -- "there will be 900 happier people every few minutes in this city, especially in the rain and cold and in rush hour" -- he is philosophical about what the increase will accomplish. In the end, he believes, no amount of additional taxis will satisfy everyone: "If they put on 900,000 medallions, maybe - maybe - there'd be enough taxis."

#####

Related Links

• Taxi and Limousine Commission

• New York Taxi Alliance

• Medallion Financial Corp.

• Committee for Taxi Safety Transportation Alternatives

• Cab Watch - Program to include taxi drivers in bringing safety to the streets.

• Fare Policy - A paper by Bruce Schaller about the effect of fare hikes on the taxi industry

•Checker Cabs - a Web site about a once-ubiquitous kind of taxicab that no longer exists on NYC streets.

#####