How The Subway Shaped New York

Although New York had long been the most heterogeneous city in the world, it took rapid transit to bring diverse social groups into regular contact. New Yorkers reacted differently to subway riding. For some, the subway’s speed and technology had a liberating, euphoric effect. Many other riders, though, resented the personal indignities of overcrowding and disliked being trapped in a small, confined space. When ethnic, gender and class differences were added to overcrowding and claustrophobia, the riding experience could be anxiety provoking.

The first subway route was the product of a mercantile elite. In 1913, though, a second stage of subway construction was authorized. The dual contract system, as it was known, was conceived by progressive reformers as an ambitious experiment in social planning designed to alleviate urban poverty and to assimilate immigrants. The dual system doubled the city’s rapid transit mileage to serve outlying portions of the Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn and allowing working class residents to move to new areas on the outskirts.

The subway contributed to the modern city by reinforcing the extent to which New York’s spatial pattern differed from that of other big American cities. New York City is among the few U.S. cities that departs from the “doughnut” pattern of low-income and decreasing population in the center and high-income and increasing population on the periphery. New York is centered on Manhattan, which has a population that is both comparatively affluent and that has high residential densities, a combination that contributes to many of the city’s characteristics: its rapid pace, its emphasis on consumption and fashion and its 24-hour operation.

Most New Yorkers live in apartments. Every morning, hundreds of thousands empty out of their apartments and commute to midtown and lower Manhattan; every night they return home. Rapid transit’s ability to transport large numbers of people quickly and efficiently permits the dense concentration of nighttime populations in residential neighborhoods and daytime populations in midtown and Wall Street.

The subway also figures in the spatial and social gulf that divides New York City from its suburbs. New York City has the nation’s highest population densities, while its suburbs extend farther than any other.

|

Avenue Subway Construction, 16th Street. 1937 |

The New York region’s distorted transportation planning is largely responsible for this. When the third and last major phase of subway construction came to an end in 1940, the metropolis became committed to the automobile and almost all new improvement consisted of vehicular highways. More than ever before, the subway set New York City apart.

While New York has had to support its own transit network, cities such as Houston and Atlanta for their transportation rely on interstate highways, which have been financed by the federal government. Beginning in the 1960s, the federal government recognized that mass transit could no longer be dealt with on a local level. The Urban Mass Transit Act of 1964 initiated federal funding of transit construction. During the resulting boom, a number of cities built light-rail systems. Because these federal subsidies have been targeted to promote the construction of new lines rather than underwrite service or the rehabilitation of existing systems, New York City had to maintain its aging subway system largely by itself, a formidable undertaking at a time when the departure of middle-class residents to the suburbs was eroding its tax base.

The failure to correct the subway’s chronic fiscal problems, along with growing competition from the private automobile after World War II, led to the system’s near collapse in the 1970s. The subway has recently experienced a renaissance, however. Since the late 1980s, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority has rebuilt every miles of track, refurbished dozens of stations and acquired hundreds of new cars. It is now considering the construction of the first new subway lines in decades, including the famously delayed Second Avenue route.

|

There is nonetheless good reason for caution. The new lines remain in planning stages and are at the mercy of changing political currents and economic conditions. Moreover, the subway’s renewal is imperiled by the financial constraints of the municipal government and the disregard of the federal government. Still, because the progress that has been made has created a new sense of hope and possibility, the subway’s second century looks promising: New Yorkers are not through making history with the subway. Clifton Hood, an associate professor of history at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, N.Y., is the author of “722 Miles: The Building of the Subways and How They Transformed New York.”

This article is excerpted from the spring 2004 issue of “The New-York Journal of American History,” the semiannual publication of the New-York Historical Society.

A Century Of Subway Activism

New York’s subways were born of activism. During the 1890s, reformers had a vision for the city. They dreamed of a reliable and inexpensive transit system that would allow workers to escape a squalid lower Manhattan and commute to and from affordable housing around town.

To a great degree, their vision came true. As subway lines opened between 1904 and 1940, so did thriving new neighborhoods from Harlem to Sunnyside to Bay Ridge. The subways shaped the city.

That tradition of activism continued, becoming particularly pronounced in the last 25 years as riders have fought to bring the subway and bus system back from near collapse.

UP FROM THE ABYSS

In the late 1970s, the decline of the city’s transit system echoed the city’s decline. The subway was notoriously unreliable, covered with graffiti and plagued with spiraling crime, fires and derailments. By 1981, subway ridership fell to its lowest level since 1917 and bus ridership also plummeted.

While city subways and buses are far from perfect today, riders and transit advocates have won tremendous progress since the early 1980s.

Today, trains are nearly 20 times more reliable than they were then. Ridership has bounced back to levels not seen since the 1950s. Graffiti on subway cars has been largely eliminated, and transit crime, fires and derailments have all been dramatically reduced.

Starting in 1997, riders could transfer for free between subways and buses — ending almost a century of griping about “two-fare zones” in neighborhoods from Sheepshead Bay to Coop City. A year later, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority began offering unlimited-ride monthly, weekly and daily passes. Today, more than half of all trips are taken on these cards.

Of course, none of this happened by accident. Since 1981, more than $30 billion (that’s billion with a B) has been invested in the subways and buses, and another $15 billion in our two commuter-rail lines.

The money was used to replace or rehabilitate every subway car and bus. The MTA expanded the subway fleet by 400 cars and increased the number of buses by 800 in order to meet growing service demands. It refurbished nearly half of all subway stations, and $750 million was invested in automating turnstiles to make fare discounts possible.

HOW TO SAVE A TRANSIT SYSTEM

How did the riders win these victories? Transit activism played a major role.

One good example is the Franklin Avenue Shuttle. The four-stop line would not exist but for local activists in central Brooklyn who struggled for more than two decades to rebuild the line, a vital transit link in Flatbush, Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Transit officials, eager to abandon the shuttle, had long neglected it. In winter, officials would routinely close the shuttle because they feared it would derail. Riders bought tokens at station booths riddled with bullet holes, and portions of platforms were sealed off because they had burned or collapsed.

But over many years, community leaders — like Helmuth Lesold, Mabel Boston and Francis Byrd — worked to restore the line. They were a constant prod at town hall meetings, news conferences and meetings with transit officials. They convinced the New York State Assembly to force the MTA to give the shuttle a $75 million top-to-bottom makeover.

The shuttle reopened in 1999, replete with bright accessible stations adorned with murals and windows created by local artists.

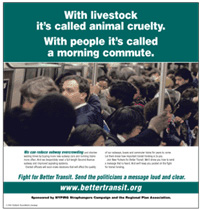

Time and again, the Straphangers Campaign, where I am staff attorney, and which is itself celebrating its 25th anniversary, has watched communities fight for their subway station or their neighborhood lines and bus routes:

- In the early 1980s, the organizing and outrage of West Side activists turned the 1, 2 and 3 from the worst subway lines in the city to among the best.

- Transit officials sought to abandon the Intervale Avenue station in the Bronx after arsonists destroyed it. But business and civic leaders protested and, in 1992, persuaded transit officials to rebuild it.

- Students at the College of Staten Island and Queensborough Community College won new bus routes to their campuses in 2001 and 2002.

(L) Pressure from transit riders and workers kept the fare at a nickel between 1904 and 1947. (R) Marilyn Ondrasik founded the Straphangers Campaign with support from the Fund for the City of New York and the New York Foundation. |

The 1980 Transit Speakout: A thousand people packed an auditorium on the West Side of Manhattan and vented on then-MTA Chair Richard Ravitch. One handed him a violin and said he was fiddling while the system burned; another said that people in the Bronx called the Number Two train the “Never Two.” A panel peppered Ravitch with tough questions, and a sixth-grader rated each answer as a “Yes,” “No,” or “Run Around.” Ravitch left discomforted, but the next day the forum made the front page of the Sunday Daily News. Ravitch carried that clipping around with him for months, waving it at state legislators who, several months later, approved a $7 billion, five-year transit rebuilding program.

Demanding Service: In 1991, New York City Transit officials proposed the most significant round of service cuts since the 1975 fiscal crisis. They held hearings and got an earful. A mother from the Lower East Side pointed out that cutting a route would force her children to transfer at a corner infested with drug dealers. Senior citizens on Grymes Hill on Staten Island showed how eliminating weekend bus service would isolate them from friends, church and shopping. To his everlasting credit, after the hearings, then-MTA Chairman Peter Stangl withdrew all the service cuts.

The Yellow School Bus: In 1995, former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani threatened to cut $128 million in funding for the student transit passes that more than half a million children rely on to get to school and extra-curricular activities. Scores of students, parents, education advocates, and elected officials crowded a public comment session to denounce the proposal. A deal saved most of the funding.

The Eyes and Ears of the Subways: In 2000, New York City Transit proposed closing scores of station booths and said no hearings were required. Along with a handful of elected officials, community groups and Transport Workers Union Local 100, the Straphangers Campaign differed. The courts agreed, the public showed up in droves, and transit officials pulled back on 112 of 177 proposed closings. (The same issue will play out in November, with the MTA proposing cutting another 164 booths.)

Now, the MTA plans to hold hearing on November 8, 9 and 10, on proposals to raise subway and bus fares. The public can make these meetings as memorable as some of those in the past. (For more information on the hearings or to comment by e-mail, go to the MTA Web site.)

Certainly, as it marks its centennial, transit needs riders’ voices more than ever. The system confronts many severe challenges.

The MTA faces large and growing deficits and has proposed fare increases and service cuts, less than 18 months after the biggest fare hike in city history. Starved by the state and city governments for adequate funds, much of the agency’s financial woes are due to soaring bills it must pay on the billions of dollars it borrowed to rebuild the system. The MTA’s debt service will double between 2004 and 2007 from $800 million annually to $1.6 billion.

At the same time, the MTA is proposing a new $27.6 billion five-year rebuilding program. This plan deserves public support because the system has critical needs, especially in its core program:

- buying new subway cars and buses;

- rehabilitating scores of dingy, outmoded and inaccessible stations;

- and maintaining the basic infrastructure.

Officials have also proposed a wide array of transit expansion projects. Some of the projects are essential to the city’s long-term future, like the Second Avenue Subway. Some are debatable, like a costly link between the Long Island Rail Road and Lower Manhattan.

But however worthy, none should move forward if the MTA cannot also continue its robust program to rebuild the existing system. New York should not go the way of London, which built a new subway line while letting its fabled Underground deteriorate.

New revenue sources are desperately needed to rebuild and to maintain fares and service at attractive levels. More than ever, we need business, labor and civic leaders and — most of all — the riders to speak up for transit.

Will Governor George Pataki and Mayor Michael Bloomberg save transit riders from having to pay more for less? Will the governor and the mayor continue 25 years of transit reinvestment and rebuilding? The odds are much better if riders ask them to.

A new round of victories would be the best way to celebrate what riders have done to win the rebirth of city transit over the last 25 years.

Gene Russianoff is staff attorney for the Straphangers Campaign.

“The Riders and the Rebirth of City Transit: 25 Years of Advocacy by the NYPIRG Straphangers Campaign” is on display at the Municipal Art Society until October 30.

Getting to the Airport

|

|

Several times a day, Wen Yen does something that many New Yorkers dread doing several times a year: he goes to the airport.

Yen has been working as a driver for a car service since 1993, trading pointers about shortcuts with other drivers, and developing his own routes and alternative routes as he shuttles passengers to and from Newark, La Guardia, and JFK.

Mainly, though, he gets stuck in traffic.

JFK is the worst of the three airports, thanks to crowded highways and poor parking facilities, but he says they are all pretty bad.

People like Yen have no choice but to travel to JFK - he drives wherever his company dispatches him - but companies like Nippon Cargo Airlines have more and more alternatives. When it was faced with a decision to send some of its flights into JFK or into Chicago's O'Hare Airport, it looked at how easy it would be to get trucks to both destinations. The company chose Chicago.

"I've had several trucking companies tell me that sometimes... it takes four hours to get from Fort Lee [New Jersey] to Kennedy Airport," said Peter Disenbach of Nippon Cargo. "When you're paying a truck driver $20 an hour, that's pretty expensive."

Getting to and from the airports is the number one issue affecting airports that were once indisputably on top.

"We're competing with so many other airports... that it's no longer guaranteed that La Guardia and Kennedy will maintain their dominance in this industry," said Jonathan Bowles, research director of the Center for an Urban Future, a local think tank that has long been advocating for airport improvements.

There are promising signs, though. The Port Authority has increased its capital investments in New York's airports, and the city is looking into improving the airports, using them to spark economic growth. In what is being touted as a good first step toward addressing the airports' transportation needs, a new Airtrain to JFK opened last year.

Most recently, Governor George Pataki has been among those advocating for a $6 billion rail linking lower Manhattan with the Long Island Rail Road and JFK. The plan's supporters describe it as the long sought one-seat ride from the airport to Manhattan. But skeptics question whether the project is the best way to solve the airports' problems - or spend the city's cash.

STRUGGLING AIRPORTS

New York is regularly named one of the country's best tourist destinations. When tourists get to the city, however, they face what respondents to a readers' poll last year in Conde Nast Traveler magazine designated the worst airport in the country: JFK. The same poll found La Guardia to be the fourth worst.

Aging terminals, long delays, and, above all, terrible transportation to and from the airports, have marked the decline of New York's airports, once seen as some of the country's best. The conditions have driven away business: JFK, the seventh busiest airport in 1991, is now 11th. La Guardia dropped from being the 15th busiest to the 20th busiest airport in the nation.

Troubling trends at the city's airports were aggravated by the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. In the first year, 10,000 airport jobs disappeared - the worst job loss of any sector in the city's economy after 9/11. The drastic decline in the airline industry nationwide tightened the market, increasing competition and further exposing the shortcomings of the city's airports.

Doubtless, there will always be passengers for JFK and La Guardia airports. But as passenger airlines and air cargo industries grow, the city may lose the benefits of this growth to its competitors.

NEWARK AND NEW YORK: COOPERATING OR COMPETING?

In recent years, Newark International Airport has undergone a $3.8 billion renewal, which was topped off in October 2001 by the opening of the Newark Airtrain. The new system, by connecting to New Jersey Transit, allows passengers to get from Penn Station to the airport in 20 minutes, and then to individual terminals in another 10 minutes.

Obviously, this benefits New Yorkers, who can get to the airport much quicker than they were able to in the past.

"New York City benefits by having all three airports available, regardless of which state the passenger takes off from, just as New Jersey benefits from having the two Queens airports available to them," said Jeffrey Zupan, senior fellow for transportation at the Regional Plan Association.

But New York's neighbor is also its biggest competitor, and the city does lose out in the form of jobs and tax revenues if business goes to Newark instead of La Guardia or JFK.

Between 1989 and 1999, for instance, the Port Authority focused on improving Newark's terminals and transportation, allowing that airport to increase its workforce by 79 percent. Over the same decade, the number of jobs at La Guardia increased by only 14 percent, and JFK actually lost nine percent of its jobs.

Because the improvement of Newark has been accompanied by decline at JFK and La Guardia, many have accused the Port Authority - which manages all three airports - of playing favorites. Former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani was so convinced that the Port Authority's approach was harmful to the city that he tried to seize control of JFK and La Guardia.

The Port Authority - which recently renewed its lease of JFK and La Guardia under terms that will give the city much more in rent - responds to accusations of favoritism by saying it spends its funds where they are needed most. In recent years, the agency has shifted capital investment back across the Hudson.

"I think it may be that things go in cycles. Newark had this great potential for growth, and the Port Authority had to help accommodate that growth. But in doing so, Kennedy and La Guardia were neglected," said Bowles. "The Port Authority has turned its attention to the New York airports."

IMPROVING TRANSPORTATION

In looking to improve the city's airports, the Port Authority's most obvious challenge is improving access. Public transportation to the airports is poor and underused; a 2002 report by the Federal Transit Administration found that only eight percent of JFK passengers used public transportation (in pdf format), while five percent of La Guardia passengers did. Most rely instead on congested highways.

JFK's problems are much worse than those at La Guardia, causing it to lose its spot at the country's top air cargo location.

The airport was the world's busiest air cargo hub until 1990; today it's the country's fifth. While transportation is not the only reason for this decline, many in the air cargo industry cite it as the most serious problem facing their businesses in New York City.

There have been calls for modest changes on the highways surrounding JFK for years: closing some exits at certain times of day, allowing commercial vans onto the Belt Parkway (all commercial traffic is currently banned), or adding a lane to the Van Wyck Expressway to reduce gridlock. Some advocates believe tolls on the Van Wyck, coupled with better public transportation, are the answer.

These changes would probably make personal travel from JFK more pleasant and commercial traffic more profitable. But no movement has been made on these proposals; there is little political will for any tampering with the city's highways.

More politically palatable are ideas that would create better rail lines, which would take riders off the highways and, theoretically, reduce highway congestion. As an ultimate solution to JFK's transportation woes, advocates have long called for the creation of a so-called one-seat ride, which would take passengers to Midtown without having to change trains.

The Airtrain

The Port Authority completed the JFK Airtrain in late 2001, a project that came after decades of debate and does not provide a one-seat ride to Manhattan. After almost a year in existence, the Airtrain is nearing its goal of 34,000 daily riders. The majority of these passengers use the Airtrain not to get to and from the airport, but to get around the airport itself. Those who connect to the subway pay five dollars to use the Airtrain; those who use it to travel around the airport itself do not have to pay a fare to do so.

This has fed the argument of those who say the Airtrain is irrelevant for Manhattanites, who have to take the subway to far-off stations in Queens and walk prodigious journeys before boarding it. This debate was one of many that raged over the project in the decades between its conception and completion. Besides being expensive - it cost $1.9 billion, paid for in part by the Port Authority and in part by a surcharge on airfare - the project generated rigorous opposition from local communities.

Such opposition is common for the ambitious transportation projects that many believe are the only way to solve the airports' transportation problems. In Astoria, Queens, community opposition caused a plan to extend the N or R trains to La Guardia to be scrapped entirely. The Airtrain itself barely passed the city's review process.

The project's supporters acknowledge that it alone cannot put a serious dent in the transportation problems at JFK.

"I know the project's been criticized for not being a one-seat ride to the airport and therefore less appealing to non-business travelers and the like," said Gene Russianoff of the Straphangers Union, a transit advocacy group that backed the project. "But it's a good first step, and hopefully in the long run we'll see a one-seat ride, at least to midtown."

Rail Link to Lower Manhattan

Tapping the post 9/11 attention on lower Manhattan, Governor Pataki and downtown business interests have been pushing to build a rail link from JFK and the Long Island Railroad, through downtown Brooklyn, and into lower Manhattan.

Before 9/11, proposed one-seat rides always terminated in Midtown. Many do not see a connection to lower Manhattan as anywhere near as useful.

The plan calls for an expensive new tunnel under the East River, and will cost a total of $6 billion. The governor's idea of paying for the project from the pool of federal grant money for rebuilding after 9/11, met tough opposition from others who had believed those funds would be better used for other purposes. Pataki has since changed course, convincing President George Bush to support converting $2 billion in unused tax credits - also part of the federal post 9/11 aid - into cash for the project. Congress still has to vote on the funding plan, and even if it does approve it, it is unclear exactly where the remaining funding will come from.

Supporters of the plan see its major feature as connecting lower Manhattan to the LIRR, spurring the downtown economy; but also describe the one-seat ride to JFK as a way to bring the airport back to the cutting edge.

The rail link "will position New York alongside other world-class cities that already have such seamless global access," said Pataki in a speech this May.

But skeptics abound, saying that the likely number of riders doesn't justify the price, and that the project overstates the economic benefit for lower Manhattan. Some see a threat to the funds needed for a 2nd Avenue subway; others fear the deterioration of the existing transportation system as capital is spent on ambitious new projects.

Whether this skepticism can be turned into support may rest on how the rail link connects to existing transportation systems: if it can be made compatible with city subways; how well stops between JFK and the World Trade Center Site serve local areas; and whether it is built to connect to any future 2nd Avenue Subway. With the project in preliminary stages, the answers to these questions are still unclear.

BUILDING ON POTENTIAL

The airports' shortcomings haven't completely hampered the ability of airlines to succeed in Queens. JetBlue Airways, a low-cost airline that is now the leading carrier out of JFK, brushed aside high real estate prices and poor transportation to set up operations in New York City.

David Neeleman, the company's CEO, was met with skepticism when he decided to anchor his company in Queens. Today, JetBlue's success has been a rare one in an airline industry struggling in recent years.

"The remarkable thing when you look at JetBlue… is that we operate out of one of the most expensive airports in the world," Neeleman told investors this summer. "Being able to be in New York…the largest travel market in the world, and being able to be efficient and use those costly assets wisely is one of our greatest secrets."

The airline is currently looking to expand at both JFK and La Guardia.

Further, the Federal Aviation Administration projects that the air cargo industry will grow by five percent every year until 2014, with international shipping appearing particularly strong. Due to its extensive experience in international shipping, JFK is particularly well suited to capture this market. Improvements over the last few years have put it in an even better position.

Through the efforts of the Port Authority, the city, and individual airlines, JFK has undergone significant changes. Several terminals have been torn down and rebuilt, much-needed warehouse space has been added, and numerous aesthetic improvements have been made.

Businesses operating out of JFK say that the improvements have made a difference. And, transportation problems aside, JFK is still a major stop for most airlines.

"It's in the center of the East Coast market ... obviously it's a major point for us," said Disenbach of Nippon Cargo, noting that the company has made long term investments in its own building at JFK. "We're going to stay here and make it work."