Selling Jewelry, Spending the Night in Jail

Also, by another street vendor in New York City:

|

||||||

I have been vending all my life, starting in Senegal, where I sold clothes, mainly those made in the United States. My dad was doing the traveling; he was bringing the merchandise from here or France, and I was selling it.

When I was first in this country I began vending too, this time making my own jewelry and clothing. I was doing festivals, state to state. I went everywhere on the East Coast, and that was good. But what I was doing, I didn’t have any life; I decided to stop. I said no more traveling.

I began to wonder “what can I do in New York?” I looked for other jobs, but they were asking me for [immigration] papers and I don’t have any. So I think, why not go into the street? I see people in the street and I ask them “what do you need to go to the street?” You just need your ID and everything, so I said let me go.

I went to the Department of Consumer Affairs, and they told me that the list has been closed for ten years. But I needed to make a living; I had to take my chances.

Vending is not that good every day, but you can make $200 a week. Even if that’s not okay, it’s better than nothing. And I’m settled; I can go home every day.

Every day I wake early. I am a Muslim, so I wake up and do my prayers really early in the morning. Monday to Friday I go to the gym by 9:30, do the stairs, or do the bike. Then I go to get my stuff from storage.

By 11:30 AM I get to my spot – 12:30 or 1:00 if it’s really cold. I always work at the same place, because it’s close to my storage, and people know me. People come and buy my things over and over.

It takes me an hour to set up. I like to make it look really nice; make the colors right. I put earrings up on a board, put the rings on the table, the bracelets on one side. I feel really comfortable with it. Even if people don’t buy one day, it makes them think about it, and they come back the next day or over the weekend.

I make my jewelry when I’m on my table. When I’m already set up, I get my chair and I make my jewelry.

If it’s cold, I stay until 8 o’clock at night. If it’s summertime I stay out until 11. I need that money, so I stay out. I wake up really early, I live really far, it takes me one hour to get home, so when I get home, I’m so tired I don’t even eat at night, I just get a bowl of cereal, and that’s all.

Since I don’t have a license, the police lock me up, they take my stuff, and I spend the night in jail. I wouldn’t guess how many times that happens. They keep coming, and coming. They are asking me for the license, they know I don’t have it, and I say â€I don’t have it.’ They say â€you’re going to have to come with us’, and I say â€Okay, I’ll come with you. You do your job, I’ll do mine.’

Still, I love what I’m doing. I don’t feel like changing my job. I â€m really comfortable with it, and I’m free. I’m my own boss.

Besides, can you imagine New York without street vendors? I go to other cities and there are no street vendors and it’s like they have no life. No sunshine.

Aiesha asked that neither her full name nor the spot where she works be revealed, because she vends without a license and does not have legal immigration status.

Aftermath of the Stansbury Killing

Timothy Stansbury Jr. was buried six days after he was shot and killed by police, but it will take much longer before the controversy surrounding his death can be laid to rest.

After a state grand jury declined to indict the officer who shot Stansbury, police are now faced with the task of rebuilding community relations, even as some city politicians and community leaders see the shooting as proof that major changes need to be made in the police department.

Then, there is the turmoil the shooting has caused among rank-and-file cops, as the 23,000-member Patrolman’s Benevolent Association has called for Police Commissioner Ray Kelly to resign. They are angry that comments Kelly made were unfair to the officer who shot Stansbury.

No Charges

The shooting will not result in homicide or manslaughter charges against the officer, Richard Neri, who shot nineteen-year-old Stansbury on the rooftop of a Brooklyn public housing development. Though Stansbury was unarmed, and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly said their appeared to be “no justification” for the shooting within hours after it happened, a grand jury cleared Neri on February 17, part of a trend, say some.

Jurors were reportedly moved by Neri’s tearful testimony that he had been caught by surprise when Stansbury, on his way to a party, opened the door. Neri reportedly also testified that he has no memory of firing the gun.

At a press conference the day after the grand jury’s ruling, Stansbury’s family denounced the ruling.

"That wasn't no accident," Stansbury’s father, Timothy Stansbury Sr., reportedly said. "Officer Neri, you need to come and tell the truth about what happened."

Federal prosecutors announced at the press conference they were beginning a thorough review of the evidence in the shooting. Neri could potentially still face criminal charges that he violated Stansbury’s civil rights. On February 26, several city council members proposed a resolution that would support a federal civil rights probe.

Not All Negative Community Attitudes

The ruling undoubtedly angered many residents in the neighborhood. But police efforts to ingratiate themselves with those living in public housing have not gone unnoticed by Tina Oliver.

“I give them an â€S’ for satisfactory,” said Oliver, a longtime resident of the Lafayette Gardens public housing development, just a few blocks from the Louis Armstrong Houses where Stansbury was killed.

Though police declined to speak for this article about their efforts to build relationships with tenants in public housing, Oliver said she appreciated things like after-school programs and Christmas parties for children organized by police, who have a headquarters across the street.

Within the New York Police Housing Bureau, there are nine divisions that work to patrol housing developments where more than 700,000 New Yorkers live. Each division has its own community affairs unit, which holds meetings at least once a month with residents in each housing development.

“They’re here to help,” said Oliver.

Change In Procedure?

Two members of the New York City Council, Charles Barron and Bill Perkins, have begun to lobby for a change in police policy, which currently allows guns to be drawn during vertical patrols in public housing. After the shooting, Commissioner Kelly announced that this procedure -- as well as police training -- would be reviewed by a special panel, but he has also said that officers should be able to decide when to draw their guns.

Barron, at a press conference, disagreed. "No officer should be carrying a gun out on the rooftops in our neighborhoods, when you know that is a normal route for passage. And if you are afraid to police us, then get out of our communities and go police a community you feel comfortable in."

Criticizing Kelly

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, at the funeral for Stansbury, reportedly said he was speaking for eight million New Yorkers who probably said, "There but for the grace of God, go I."

But many police must empathize more with Officer Neri, an 11-year veteran who had never fired his gun while on duty before shooting Stansbury. The Patrolman’s Benevolent Association has called for the resignation of Commissioner Kelly, citing his public judgment after the shooting.

"The commissioner does not afford the benefit of a doubt to the very police officers who risk their lives to make this city safe," said Patrick Lynch, head of the 23,000-member union.

The decision by the police union to go after Kelly, who recently enjoyed a 70 percent approval rating among New Yorkers, occurred after 400 delegates gave a vote of “no-confidence” in the commissioner. Many of these delegates chanted, “Kelly must go,” at a press conference announcing the PBA’s position.

"The message that commissioner Kelly has sent to New York City police officers is: do your job and risk your life, but you are on your own."

The no-confidence vote may not amount to much. Many have praised Kelly's quick reaction denouncing the shooting, including Mayor Bloomberg, who also criticized the police union.

"We should take a non-confidence vote in the PBA. We have the best police commissioner this city has ever seen. He's done exactly what's right…Cover-ups are not in anybody's interest -- and it's certainly not in the interest of the world's greatest police department not to go out there and be open,” Bloomberg told Newsday.

Neri is currently on modified duty, without a gun or a badge, and may still face police department disciplinary charges.

Internet resources for what you need to know about NYC Crime and Police

|

Most New Yorkers probably think that government learned a great deal from September 11 about protecting the city, its symbols, landmarks, and people. The attack's immediate aftermath saw a barrage of reassuring official actions that were military-like in their precision -- securing vital areas, shutting down ground access to the city, and patrolling New York's perimeter from the skies and seas. In the months since, the official presence has withdrawn from the skies and the streets, but most New Yorkers assume hopefully that this retreat masks ongoing work behind the scenes. Citizens have no way of knowing for sure, since all anti-terror operations are secret. For those who agree with the former city official who told Richard Cohen of the Daily News that the September 11 attack meant that "the government let us down," the secrecy is yet another barrier to evaluating government actions.

Most New Yorkers -- 72 percent -- believe another terrorist attack is very or somewhat likely, according to a poll conducted by Blum & Weprin for the Daily News. A plurality of 28 percent speculate that it will probably involve smaller-scale car bombs or suicide-bombers, while 20 percent anticipate the use of biological weapons and 16 percent expect chemical weapons. Still, 72 percent say they feel safer or as safe in the city as anywhere else in the country. Are they right?

THE NYPD PROJECTS COMPETENCE

September 11 badly damaged public confidence in the federal security agencies -- the FBI and the CIA -- but enhanced confidence in the NYPD, which immediately went onto Omega Alert, its highest state of readiness. Through what Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly calls "target hardening" it has since been able to reduce the number of officers assigned to Omega posts Ă‘not an insignificant matter since some violent crime, including rape, seems to be heading back up.

Nonetheless the New York Police Department has been refocusing the problem-solving strategy that helped reduce violent crime from local crime to terrorism. The strategy's specific elements, according to policing expert George Kelling, are accurate and timely intelligence, rapid deployment, effective tactics, and relentless follow-up and assessment. The media have contained many accounts of both historic and recent federal stone-walling of the NYPD on intelligence, the greatest federal failing, of course, on September 11. All parties now insist publicly that this is a problem of the past.

Perhaps it is. The NYPD is led by a police commissioner, Raymond Kelly, who has far stronger federal security credentials than any previous commissioner. His federal experience helps him in the many instances in which the NYPD tangles with the FBI and the federal Department of Justice over jurisdiction. As Cooper Union historian Fred Siegel says, "In a time in which the distinction between war and crime has narrowed, Kelly has already worked in positions in which he had to deal with this reality. Given that we're a target in New York, it's a huge asset that he's in a good position to make a difference."

Kelly has been aggressive, assigning NYPD personnel to areas that were once exclusively federal -- training some cops abroad, sending brass to the Naval War College, expanding the intelligence office to include foreign terrorism, and setting up a medical office to coordinate with federal agencies and the city's Department of Health on biological weaponry.

He has brought in high-level people with federal experience. He hired Ret. Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Frank Libutti as Deputy Commissioner for Counterterrorism to head a new division on counterterrorism and to direct the department's work with the FBI/NYPD Joint Terrorist Task Force. The idea is to ensure cooperation and flow of information between the agencies Ă‘not a strength in the past. Libutti oversees the new Terrorism Security and Analysis Section, which conducts comprehensive security assessments of terrorist threats in the city. An Incident Response Team has been set up to respond to requests for assistance at suspected terrorist events. Kelly also hired a former top CIA operative, David Cohen, as the new Deputy Commissioner for Intelligence. Both deputies report directly to Kelly, who also established a new position of medical adviser to coordinate with the Department of Health.

How effective are these measures? We're unlikely to know unless -- probably until -- there is another attack. Over the last decade, the city has been the target of at least three other known terrorist plots: the 1993 truck bombing of the World Trade Center; the 1993 plot to bomb the United Nations and the Holland and Lincoln tunnels; and the 1997 plan to bomb the subways. New York remains the symbol of capitalism and Western culture, and a target.

SECURITY MEASURES AGAINST THE THUG AND THE TERRORIST

Even before September 11 New Yorkers had become accustomed to security measures deterring the common thug: metal detectors, photo IDs, bag searches, checks of electronic equipment. The devices are often primitive and the training of the personnel poor, but routine security checks have prevented at least some crime and perhaps some terrorism. The future, however, lies with high-tech solutions that are independent of human judgment, such as new sensing machines that can detect biologic agents, explosives, suspicious voids in truck cargo, or weapons hidden on someone a distance away. Private companies tend to be way ahead of government in spending the millions of dollars these machines cost.

The other set of measures are what the security trade calls Israeli tactics -- traffic-stopping checkpoints, street closings, intrusive questioning, random identification checks, intimate searches, and racial profiling. These are ostensibly meant to deter crime, but they are also meant to remind the public often and aggressively of the presence of terrorists and to get the public to accept the authority of the police and military. The inconvenience that accompanies these tactics is deliberate.

Giuliani's NYPD actually introduced a few of these ideas, such as the traffic-stopping checkpoints that were ostensibly for drunk-driving or seat-belt use. His 1998 pedestrian-controlling concrete barriers are another Israeli tactic, a re-engineering to encourage people to go only where they are directed and to accustom the public to accepting restrictions on their movements.

Street closings, immensely disruptive to the city's business and psyche, are increasingly being insisted on by powerful interests, including the federal government. The main federal building in Lower Manhattan, 26 Federal Plaza, has always had security problems. It houses the FBI field office that has investigated many terror plots. It houses the Immigration and Nationalization Service. Lines of anxious immigrants with federal applications snake around the building during peak periods. In late 2000, the General Service Administration installed barriers and posts and hired additional guards. Some federal officials are now urging the closing-off of Broadway(the main artery downtown), Centre Street (which leads to the Brooklyn Bridge), and Worth Street.

The public has very limited access now to most government buildings in New York. The new federal courthouse, for example, is blocked by a huge hydraulic truck barrier. Police headquarters, never really accessible since it was built during the Lindsay administration, has a 24-hour guard out front. Visitors must go through three checkpoints, carrying a government-issued photo I.D.

One bright spot on this glum governmental scene, however, is City Hall, which Mayor Bloomberg has re-opened to political events. press conferences and peaceful gatherings . They are again allowed on the steps of City Hall, as they had been from the early 19th century until the Giuliani administration.

And it's not just public buildings that have internal checkpoints and external barriers. Ugly concrete bolsters are being installed in front of otherwise handsome new buildings, like the Jewish Community Center on the West Side. The elegant glass, iron, and greystone building would be a beauty, if its exterior were not marred by white and yellow blocks of junky concrete, looking as if a sloppy contractor forgot to take them home.

NEW YORK IS NOT AN ISLAND

Much as it will seek to protect itself, New York will only be safe insofar as others protect it as well. The plane that flew into the World Trade Center took off from Logan Airport in Boston, an airport that the Federal Aviation Administration has repeatedly cited for safety violations. Everyone wants whatever went wrong at Logan Airport in Boston fixed. But what was it that failed? And will the FAA's new proposals and restrictions on passengers work? Are tactics like the FAA's ban on steak knives in first class or the abolition of curbside checking effective? Certainly neither would have prevented the hijackings.

Mary Schiavo, former inspector general for the U.S. Department of Transportation, argues that aviation security is a law enforcement function, and belongs with a law enforcement agency, not the FAA. Law enforcement officials would be far less ready to listen to concerns about the weight of new cockpit doors (additional weight would affect the cost of every flight), or the extra costs of sky marshals or deputized pilots.

New York has an acute interest in these issues, and in all matters having to do with its air space. In May the FAA announced that its ban on flights by small planes and helicopters over key American cities had been lifted. Planes could return to flying under visual flight rules without asking permission to enter a city's airspace, or identifying themselves to FAA regional or local controllers.

Even before the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, local officials had often been at odds with the FAA, which maintains that all small aircraft should be able to fly low, with no restrictions, over major cities and national monuments. This is in part because the FAA's role is to promote the aviation industry Ă‘not police or regulate it beyond preventing collisions. They argue that flying freely anywhere in the country is a basic American right and expectation. As an FAA representative said at a community meeting in Manhattan, the same rules that apply over Kansas wheat fields apply to flying over New York City.

There is little doubt but that Al Qaeda intends to use small planes to attack more targets. Plans to pack a corporate jet with explosives were found in a German apartment rented by suspected Al Qaeda terrorists. Cell members in the U.S. trained at flight schools, obtained small-plane pilot licenses, and sought to rent crop dusters. The FBI renewed its warning about air attacks in early July.

Even the FAA concedes that some landmarks may be vulnerable. Deferring to its sister federal agency, the National Park Service, the FAA in late June banned flights near the Statue of Liberty, Mount Rushmore, and the St. Louis Gateway Arch during the July 4 holidays. The Statue of Liberty ban will continue through September 30, and forbids any plane from flying below 1,500 feet within a 6,000-foot radius of the statue.

These bans may be comforting to some, but they are not significant security measures because the FAA has no air police to stop a plane violating its rules. It can only suspend the pilot's license and levy a fine. The NYPD, though it has an aviation unit and some older helicopters, has no official enforcement role or authority in the air over the city.

Anyone with a license can rent a plane at many of the approximately 2000 general aviation airfields within a short flight of New York. Few of these have more than the most minimal security. Pilot licenses, which are easily forged and carry no photos, are seldom verified. Planes, which can fly into these fields from almost anywhere in the US, are not inspected before departure. Helicopters do not even need an airport for departureÑand in any case can stop anywhere to pick up anything.

So long as New York's skies are open, the city is undefended. An attacker boarding an airplane at LaGuardia faces far more government inspection than one flying a plane at 700 feet across 42nd Street.

Sites For Beginners:

- New York Police Department - Hokey design but good substance, particularly the feature that allows you to check out your own neighborhood. The department has begun posting crime figures for each of the city's 76 police precincts on both its own and City Hall's official websites. Precinct maps show where crimes have recently been committed. One drawback: the only official you can email is the commissioner. Still, that's better than nothing--if the commissioner reads and answers his email. Let us know what happens when you try.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, Unit for Crime Reports- The FBI's uniform crime reports are the nation's most useful tracking system for both violent crimes (murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault) and property crimes (burglary, larceny and theft, car theft, and arson.)

- Vera Institute of Justice - Vera is a nonprofit organization, founded in 1961, that works collaboratively with government officials to develop innovative approaches to problems and to improve the quality of urban life both here and abroad. It is currently working with both the New York City and New York State police departments to strengthen police accountability through civilian complaint review, community policing, and computerized management systems.

City Settles Discrimination Lawsuit By Black And Latino Officers

A long anticipated trial over discrimination at the New York City Police Department was averted when the Latino Officers Association, the City of New York and the department reached a settlement shortly before the trial was scheduled to begin.

The lawsuit, commenced in 1999 by 22 individuals and the association, was certified as a class action three years later by Judge Lewis A. Kaplan of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. The class includes all African-American and Hispanic police and certain civilian employees of the New York Police Department from 1995 on.

Charging that the police department violated their city, state and federal civil rights, the plaintiffs alleged a hostile work environment where they were subjected to derogatory remarks, racist graffiti on lockers and similar conduct which was often tolerated by superiors. One of the worst problems was retaliation against officers who complained, according to the plaintiff's lead counsel, Richard Levy, who said the officers became "outcasts in many precincts." The plaintiffs also alleged disparate and discriminatory application of disciplinary rules and procedures. The lawsuit maintained that disciplinary charges were brought against blacks and Hispanics more often than against white officers and that more convictions were returned and more serious penalties were imposed for departmental convictions resulting in transfers, denials of benefits, suspensions and terminations. The charges against the officers ranged from rudeness to murder. Most fell into a generic category of conduct prejudicial to the NYPD.

Statistics relied on by plaintiffs indicate that when civilian charges against police officers originated at the Civilian Complaint Review Board, an independent non-mayoral agency cited for comparison purposes, disparities based on race or ethnicity were minor or non existent. In complaints filed by the public, blacks were charged at the same rate as whites; the figures for Hispanics were slightly more. However, when charges originated internally at the New York Police Department, overall disparities increased enormously with blacks and Hispanics much more likely to be charged than their white counterparts.

Similarly, when departmental trials were held, blacks were much less likely to be acquitted and have their charges dismissed, than whites. In fact, if the case, Latino Officers Association against City of New York and NYPD, had gone forward, the plaintiffs expected to prove that blacks were 60 percent more likely and Hispanics 30 percent more likely to be found guilty at departmental trial than whites. In terms of overall dispositions, charges against whites were more often dismissed, or resulted in findings of not guilty, while African-Americans and Latinos were far more often found guilty. In addition, when findings of guilt were handed down, blacks and Hispanics were terminated from the police force with greater frequency than white officers, who received lesser penalties.

If the settlement is approved by the court as expected, the class, which includes approximately 12,000 members, and their lawyers, will share a monetary settlement of $26.8 million of which 20 million is dedicated to claims and two million to administration. A panel is to be created to decide how many of the Hispanic and African-American members of the police force who served since 1995 may be eligible to share in the settlement and to what extent. It is not known how many claims will be submitted, or how many members will "opt out" and settle, litigate or withdraw their own cases. Claims may also be filed for lost benefits, but there are no provisions for reinstatement of individuals whose employment was terminated. The awards can range from $3,500 to $400,000.

In addition to the monetary provisions, the settlement includes an injunction against discrimination by the police department. While the defendants do not admit any wrongdoing, they accept that the police department is enjoined from discriminating based on race, color, national origin or ethnicity in the future. "The injunction outweighs individual recoveries," said lawyer Richard Levy. "It opens the door to a new day when black and Latino cops are not mistreated."

The settlement also requires the establishment of a review unit to analyze the NYPD's disciplinary process regarding discrimination and retaliation and whether African American and Latino/Hispanic members of police service are being investigated, charged or penalized in a discriminatory manner. The proposed order which is being submitted to Judge Kaplan for his approval and signature details the steps the police department will take to establish procedures to prevent discrimination.

All members of the certified class can apply for awards from the fund which is to be held by the New York City Comptroller; payment is to be administered by the Special Masters Kenneth Feinberg and Peter Woodin. Mr. Feinberg also heads the federal program of compensation to families of victims of the September 11th attacks. According to plaintiffs' attorney Richard Levy, "the case would not have settled without the Special Masters. We couldn't have achieved the results," he said. "But Feinberg had immediate access to Mayor Bloomberg, Police Commissioner Kelly, and Mike Cardozo [Corporation Counsel]. No one would meet with us at this level before."

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

Operation Impact And The Shooting Of Timothy Stansbury, Jr.

Atop a Brooklyn roof, a single bullet from one cop’s gun pierced the chest of a nineteen-year old last month, ending his life and sparking yet another firestorm over police tactics. Timothy Stansbury, Jr. was armed only with a stack of CDs, on his way to a party via a rooftop shortcut, when he was shot at the top of the stairwell in his building, a public housing project in Bedford-Stuyvesant, by Officer Richard Neri.

Neri and other officers were patrolling the rooftop of the building, reportedly trying to open the door to go downstairs at the same time Stansbury and his friends were trying to use the same door to reach the roof. Whether Stansbury, Jr., was the victim of an accident or something criminal, a grand jury will decide. But while some focused on the swiftness with which Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly condemned the shooting as unjustified, as well as Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s quick arrival on the scene to comfort a grieving family, on the streets the story was about the police.

“The police see you and think you’re a suspect,” said Samuel Jackson, 20, of Crown Heights, calling police in his neighborhood disrespectful and overly aggressive. Jackson was reacting not only to the Stansbury shooting, but to a police effort widely hailed as a triumph by city leaders.

Last January, the story in Crown Heights was Operation Impact, a police effort involving bulked-up patrols in high-crime neighborhoods, in some cases, areas as small as a subway station or housing project. The police effort reduced total felony crimes in the targeted areas by 33 percent, from 11,033 to 7,421.Those numbers probably contributed to an FBI rating announced in December that put New York City among the safest cities with a population of 100,000 or more. City officials proudly trumpeted the success of Operation Impact when announcing last month that the program would be expanded. Operation Impact II will involve more police officers and stretch across more police precincts.

Crown Heights was where the original Operation Impact was first announced, and the increased police presence has not gone unnoticed. But while no one denied the need for police in their neighborhood, police tactics were openly questioned.

Jackson described tales of harassment that ranged from the trivial (he was told to go inside while drinking a beer on a stoop) to something more than that (he was pulled over while in a cab, searched and then “left like a dog.” )

He is not alone in expressing concerns about police conduct. Across the city, 5,581 people issued complaints about New York police last year, a 21 percent increase from 2002 and the highest number since 1995, according to a report by the Civilian Complaint Review Board released last month, as reported in Newsday.

Nevertheless, shooting incidents have decreased substantially for the police precinct, the 77th, which includes Crown Heights. Shootings numbered 64 in 2003, a reported 15 percent decrease from 2002. Police had reported a 41 percent increase in shooting incidents from 2001-2002. Homicides, however, remained unchanged, numbering 15 in 2002 and 2003.

Zeroing in on the impact areas, the numbers are rosier for the city overall. Shooting incidents in the impact zones decreased 30 percent, from 184 to 128. Homicides decreased 39 percent in the troubled areas, from 49 to 30.

Operation Impact II will send more than 1,000 police officers to 52 so-called impact zones, each chosen based on a statistical analysis of crimes. The officers, fresh graduates from the police academy, will join about 700 officers already working in the impact zones. Many of the new officers will be on foot patrols, and they will work with more veteran officers.

With public safety one issue where New Yorkers seem satisfied with city officials (Police Commissioner Ray Kelly had an approval rating of 70 percent in one poll)

Mayor Bloomberg mentioned three other recent police initiatives in his 2004 State of the City address:

Brooklyn Gun Court

Brooklyn Gun Court began last April. One judge was assigned to hear only felony gun possession cases from five of the most violent police precincts in Brooklyn, following each case from arraignment to sentencing. The results have been more convictions and lengthier sentences. Of the first 97 cases heard in the court, 99 percent resulted in convictions. The court has also largely done away with strictly probationary sentences, and the median jail time increased from 90 days to a year.

Mayor Bloomberg announced an expansion of the program in December, with similar courts now established in Bronx and Queens. An estimated two-thirds of all felony gun prosecutions will be funneled through the gun courts, with the Bronx Gun Court expected to process approximately 270 cases per year and the Queens Gun Court expected to handle about 175 cases. The Brooklyn Gun Court will now hear cases from seven police precincts.

“Gun cases are processed quickly, adjudicated fairly, and are sentenced in accordance with the state mandatory minimum laws,” Bloomberg said in a press release announcing the expansion of the program.

Operation Spotlight

Operation Spotlight established specialized courts designed to speed-up the handling of what Bloomberg called career misdemeanor offenders at a press conference announcing the initiative.

The program began in July of 2002. Even as the city struggles with the financial burden of housing inmates at Rikers Island, that seems to be the destination for criminals going through the spotlight courts, though offenders can also be sent to drug treatment through the program.

The percentage of defendants receiving jail sentences has increased 48 percent, with sentences of more than 30 days increasing 75 percent.

Operation Silent Night

Launched in October 2002, Operation Silent Night initiative identified 24 high noise neighborhoods throughout the City based on the number of complaints. More than 30,000 more quality of life police summonses have been issued in the first four months of the fiscal year (July 1 through Oct. 31) than those same months in 2002, and city officials have pinned the increase in part on Operation Silent Night and Operation Impact. Newsday reportedthat noise violations rose 31 percent to 4,648 in fiscal year 2003.

“I think from a public perspective it is terrific,” said Arline Bronzaft, a consultant to The Council on the Environment of New York City. However, Bronzaft questioned whether the city was any less noisy. Bronzaft said she was optimistic about a revision of the noise code, which she said has the support of the mayor’s office. Bronzaft said a draft of the code could be made public this month if approved by city officials, and brought before the City Council soon after.

Crackdown In The Schools

City officials have cited Operation Spotlight and Operation Impact as the model for the program in place to clamp down on violent crime in schools, according to articles in the Times and Gotham Gazette. Like Operation Impact, the school program uses statistical analysis to decide which school is an “Impact School.” Chronic troublemakers with two or more principal or superintendent suspensions within a 24-month period will be dubbed “Spotlight Students” and subject to more stringent punishments for subsequent misbehavior.

Civil Liberties And Police Surveillance

Critics of New York Police Department policies instituted in the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks ended the year with a sense of anticipation-and disappointment.

A new, non-binding City Council resolution seeking to reaffirm the importance of civil liberties for New Yorkers became the victim of bad timing, as a vote on the resolution scheduled for December 15 was postponed until January following the capture of Saddam Hussein by military forces. (See December Lawtopic page)

Leaders from the New York Civil Liberties Union anticipate that the resolution will be passed when the council resumes in January. The resolution includes strong language against New York Police Department surveillance policies and also calls for the department to release statistics involving the number of searches done under the U.S. Patriot Act (under the law, such searches are done without the knowledge of the person being investigated).

The resolution, if passed, would be among scores of others passed nationwide in response to the Patriot Act. But in New York, there have already been several complaints about police practices that have left many civil libertarians disappointed with New York police.

Handschu Gone, But Not Forgotten

A 1971 class-action lawsuit forced the department to adopt guidelines in 1985 that require proof of an actual or imminent crime before investigating political activities. Those guidelines, known as the Handschu guidelines, were criticized by police as a roadblock to gathering information about potential terrorist organizations post-September 11. For example, a complex money trail potentially leading to and from potential terrorist organizations, or speech inciting people to "rise up" against the United States could not lead to further police investigation, as long as such actions remained within the letter of the law.

The city fought successfully to repeal the Handschu decree, reportedly at the urging of Deputy Commissioner of Intelligence David Cohen, who worked for the Central Intelligence Agency for 35 years. Federal Judge Charles S. Haight ruled last January in favor of the police, relying on affidavits from Cohen that testified the Handschu decree was not workable in the "context of terrorism."

However, the same judge reprimanded the police for their interrogation of protestors arrested at a February anti-war rally. Though police claimed that they asked questions from a "debriefing" form (which itself drew a raised eyebrow from Haight), 12 protestors signed affidavits saying that they were asked such questions as "Do you hate George W. Bush," and "Don't you think it was necessary for us to get involved in World War II?"

Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly and Cohen both said they did not know about the "debriefing" form, raising questions voiced by attorneys about whose orders some of the 37,500 police officers seemed to be following.

For his part, Judge Haight said that he thought his original ruling struck a proper "balance between the legitimate demands of public security and individual freedoms." But after reviewing the complaints from protestors, Haight said, "I no longer hold that confidence."

What's Next?

For all the bad publicity and harsh words from Haight, the only change following the February incidents was that the police's surveillance policies were themselves placed under court supervision, a hand slap viewed by police as inconsequential.

And while the resolution before the City Council seems to show that civil liberties can be made into a citywide political issue, the idea that the so-called New York Bill of Rights will affect change in police policy-or even lead to the release of information such as how often education or library records have been pulled by law enforcement, as called for by the resolution-seems a dubious proposition.

Looming this year is the Republican national convention, a good bet to draw some sort of rally against Republican policies. Should any protestors be arrested, the courts and civil liberties groups like the New York Civil Liberties Union will be watching to ensure that no inappropriate questions are asked by police.

The Bill Of Rights Resolution

Q. What do Albany, Ithaca and Syracuse have that New York City does not?

A. A Bill of Rights Resolution.

Immediately following the September 2001 acts of terrorism, with little public debate, the U.S. Congress enacted the USA Patriot Act, and then the Homeland Security Act, followed by new federal orders, rules and regulations. Critics say many of these contain provisions infringing on civil liberties and civil rights. In response, three states, Alaska, Hawaii and Vermont, and, as of this writing, 227 cities and towns including 13 in New York State, have adopted resolutions in support of individual Constitutional rights. On the anniversary of the adoption of the Bill of Rights (December 15, 1791), despite the urging of a coalition called the New York City Bill of Rights Defense Campaign, the City of New York failed to join the list.

"The protection of civil rights and civil liberties is essential to the well being of a free and democratic society," the proposed resolution begins. "The members of the Council of the City of New York believe that there is no inherent conflict between national security and the preservation of liberty. Americans can be both safe and free."

The Bill of Rights Resolution, or Resolution 909, was introduced last May by Councilmember Bill Perkins, and cosponsored by 32 out of 51 members of the council. But it failed to come to a vote; support eroded on the last possible day because many members felt that the public would misunderstand its passage coming so soon after the arrest of Saddam Hussein. Speaker Gifford Miller has promised to bring the resolution back before the full council in January.

"We, as a city of eight million, can make a statement about federal law that speaks out against aspects of the Patriot Act, certain injustices and violations of civil rights and civil liberties, of Americans and immigrants," Perkins said in a telephone interview "The NYC Council must take a stand and go on record against secret detentions without charges or access to counsel; spying on lawful political and religious speech; and ethnic and religious profiling."

Udi Ofer, an attorney with the New York Civil Liberties Union, adds that "fighting terrorism does not mean conceding our freedoms, and Resolution 909A gets that message across loud and clear."

The new federal legislation and companion policies vastly increase the investigatory and surveillance powers of law enforcement, making enormous changes in the areas of privacy, and the rights of persons investigated or accused, or merely under suspicion in connection with alleged terrorism or based upon ethnic, religious or political grounds. Law enforcement and intelligence agencies are given unprecedented access to personal medical, financial, library and educational records, as well as Internet habits, search warrants, electronic surveillance. The new legislation also authorizes indefinite incarceration without counsel of non-citizens and those designated as "enemy combatants."

David Cole, Georgetown University Law School professor of constitutional law and author of ENEMY ALIENS, said that the Bill of Rights is not limited to citizens, the way voting is.

Because 909a is a resolution rather than a statute or ordinance, it would not have the force of law, nor the power to undo what Congress has enacted. However, the resolution would require federal authorities to disclose the circumstances surrounding New Yorkers arrested or detained in connection with terrorism investigations. It would also express support for the rights of immigrants, and express opposition to investigations based on activity protected by the First Amendment; to racial, religious or ethnic profiling; to unreasonable camera surveillance and searches; and to secret detention without charges nor access to a lawyer. The resolution would have called upon federal, state and local officials and New York City agencies and institutions to affirm and protect civil rights and civil liberties.

"I think the movement to pass these resolutions is the single most effective tool to raise the consciousness about the importance of civil liberties in the USA that has been undertaken since September 11th," Professor Cole said. "There is a real shift in public attitudes about the importance of protecting civil liberties and it's not because of the courts or Congress or executive orders, but what people around the country are saying in adopting these resolutions."

The resolution, which was endorsed by most of New York City's congressional delegation, also urges New York's Senators Charles Schumer and Hillary Clinton to take leadership roles in preventing passage of the pending Domestic Security Enhancement Act, or Patriot II.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice.

After Rikers

An ambitious new city plan to help ex-offenders find jobs, affordable housing and drug treatment probably wouldn't have meant much to Clifton Murrell -- not when he was at Rikers Island, serving a yearlong sentence on charges of possessing cocaine and weapons.

Murrell remembers getting a booklet outlining existing programs designed to help prisoners plan their future on the outside - how to line up work, stay sober, and so on. Murrell never signed up for help; planning for his future seemed laughable to him while he was incarcerated. "You're in survival mode," he said. Rikers Island is "not really a place of" -- he pauses, a slight smile on his face -- "rehabilitation."

But now Murrell is out, and along with a dozen men and women early on a Monday morning, he is seeking help in the offices of The Fortune Society, a non-profit that has been helping ex-offenders since 1967. Some in the office profess confidence that they will find the job or education they need to keep from returning to old ways; others, like Murrell, admit to nervousness about what their future holds with a checkered past behind them.

City officials must be a little nervous, too. They are banking on a new program, funded by a $7.5 million federal grant and unprecedented interagency efforts, to help ex-offenders stay straight.

"It's something I really applaud. It's long overdue, badly needed and a real start in the right direction," said JoAnne Page, executive director of The Fortune Society. The new city efforts, however, are very much a work-in-progress, and the challenges are many in helping ex-offenders find success.

NEEDY POPULATION

Rikers Island, a little more than half a square mile of land sitting in the East River between the Bronx and Queens, has been the site of the city prison since 1935. Today, Rikers Island consists of ten separate jails, which together house about 13,900 prisoners.

Most inmates are in for only a few weeks as they await court dates; the maximum stay at Rikers is one year. (Longer sentences are served in state prisons.) The new city program seeks to help prisoners getting out after at least three months.

The Rikers' population isn't filled with violent criminals, but it poses a huge challenge to city social services. According to The New York Times, 80 percent of inmates have drug problems, 30 percent have no home, and 15 percent are mentally ill. The city's Department of Correction "runs some of the most expensive housing in the city," said Page. It reportedly costs about $50,000 a year to house each prisoner, a cost widely publicized as justification for the expensive new city program.

Prisoners with AIDS and mental illness already get substantial city help, though it took a class action lawsuit to loosen city purse strings for mentally ill ex-offenders. A judge ruled against the city earlier this year in a lawsuit filed in 1999 alleging the city was negligent in helping mentally ill ex-offenders find treatment upon their release.

The city fought the lawsuit, known as the Brad H. lawsuit, and appealed a state trial court decision, but in January settled, agreeing to provide services.

"I think if the Brad H. lawsuit hadn't happened we'd be way farther behind," said Page.

Page and others, however, credit the new commissioner of the Department of Correction, Martin Horn, as a driving force behind the new program. Horn was appointed to the post in January by Mayor Michael Bloomberg after serving a one-year stint as Commissioner of the Department of Probation.

"I've known the commissioner of corrections for a long time," said Page. "I've got a lot of respect for him.” Horn has organized daylong meetings with officials from various city departments, with the Department of Homeless Services expected to play a big role in whatever solutions the city comes up with. But the details of the program remain largely unresolved. Of the three main areas of city efforts -- drug treatment, housing and jobs -- so far, only the jobs portion is up and running.

JOBS AND BEYOND

Existing employment services for ex-offenders have differing philosophies. For example, at the Fresh Start program, run by the Osborne Association, "the basic idea is to get them excited about something," said Leigh Owens, a case manager. That program offers mini-courses in computer journalism or culinary arts, which might seem overly ambitious but often result, according to Owens, in Microsoft certification or a food handler's license, all paid for by The Osborne Association.

That philosophy contrasts sharply, however, with the main goal of the new city jobs effort, which is basically a jobs creation program offering immediate work and immediate pay for ex-prisoners, including ferrying newly released offenders from Rikers Island directly to work sites scattered across the city.

The first day out might be a job lasting from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m.. Work includes grounds-keeping and litter removal on state highways in the Bronx and Queens, as well as work in and around housing projects in Upper Manhattan and Brooklyn such as whitewashing and clean-up. The work is typically done in groups of about six, with one on-site supervisor. Workers earn federal minimum wage but get a check at the end of each day, usually about $30.

The city program has two tracks, a two-week track and a six-week track, with ex-offenders with the least work history going on the six-week track. Ex-offenders will work four days a week, with one day of job counseling.

The idea is to try and simulate a real job situation, which means participants in the program might have long commute times. This way, former inmates can prove that they can show up for work on time every day, perhaps the most important trait employers look for when hiring new workers. The program includes an aggressive outreach program that seeks out employers willing to hire ex-offenders.

The Center for Employment Opportunities, a non-profit that has been offering similar programs for about two decades, won a three-year contract with the city to provide the job services. The method works, according to the organization, as in the past more than 60 percent of its "graduates" have been placed in full-time jobs within three months of finishing the program.

So far, only about 300 ex-prisoners have gone through the new city program, which began in August. The jobs program aims to help 2,800 prisoners by June, 2004 and about 5,000 prisoners once the program is at full-capacity. Expansion will likely involve more outdoor worksites.

WILL IT WORK?

Jobs are important, but they are only one piece of the puzzle when it comes to what experts call "discharge planning." Page notes that there are "so many things working against good discharge planning." Nationally, two out of every three ex-offenders are rearrested within three years of release.

Housing is a huge issue in New York, Page stressed, adding that the new city program must overcome existing laws and regulations targeting those found guilty of crimes. People that have certain criminal records can't live in public housing.

"Some of it is law and some of it is administrative practice," said Page, explaining that federal restrictions are really primarily about sex offenders and people who manufacture drugs. New York City has tighter guidelines, for example excluding ex-offenders from public housing for drug offenses.

"The consequences are devastating," Page said.

Owens agreed that environment plays a big role in whether or not an ex-con can stay an ex-con.

"One of the biggest problems is the surroundings, them going back into the same settings …it kind of negates your progress sometimes," said Owens.

Of course, attitudes of ex-offenders must be changed, as too many see their criminal record as an insurmountable obstacle in finding steady work. Who will hire an ex-con? But Owens, like many on staff, did his own stint behind bars, serving a yearlong sentence at Rikers Island for felony gun possession, he said. Another ex-prisoner is Maria Perez, a counselor at The Fortune Society for almost seven years. She first came to The Fortune Society because she was mandated to attend substance abuse counseling after serving time on a drug charge.

"We are living proof that it works," said Perez.

There have been no comprehensive studies that see whether recidivism rates change as a result of careful planning for discharged inmates, according to Nicholas Freudenberg, a professor and director of the Program in Urban Public Health at Hunter College. Freudenberg has worked with prisoners in city jails for more than a decade and serves on advisory boards to the new city program.

He sees the program as a good start, but also said it will need to be judged by the resources that are put into it, and can only be judged over time.

"In watching city government for 25 years," he said, "the city can lose track of a problem, especially when it's a complex problem that requires collaboration over different city agencies."

A Case Of Rape And Murder

Keila Pulinario testified at her 1997 murder trial that Imagio Santana had raped her and then bragged about it to his friends. When she confronted him some days later about it, he laughed and threatened to rape her again. That is when she shot and killed him. She was convicted by a jury and is serving a sentence of 25 years to life, the maximum sentence, at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility.

The conviction was affirmed by two New York State appeals courts, but now, five and a half years after the trial, federal Judge Jack Weinstein of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York in Brooklyn has granted a writ of habeas corpus -- literally, “release the body” -- ordering New York authorities to either release or retry Pulinario.

The case offers yet another glimpse into the crime of rape, which is the most under-reported crime in the United States. According to Department of Justice figures, two thirds of all rapes are not reported. In New York City last year, according to the New York Police Department, 2,013 rapes were reported, which represents an increase, while most other crimes have decreased.

At the time of the shooting, Pulinario was a 21 year old victim of childhood sex abuse. She could neither read nor write, and had an I.Q. of 70. She had no criminal record, though she admitted she had used and sold drugs in the past. Santana, who had a sex offense charge pending involving a 14 year old girl, was a drug dealer and user; an autopsy identified the presence of heroin, cocaine, marijuana and methadone in his body.

While the prosecution’s theory was that there was no rape and that the defendant was guilty of murder in the second degree, the defense to the shooting was that Pulinario was raped and suffered rape trauma syndrome (RTS) and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The defendant’s legal position was that she was not criminally responsible because of mental disease or defect; that an emotional disturbance caused the defendant’s actions. The defense also claimed that the shooting was a justified act of self-defense.

The defendant’s expert witness, Dr. Linda Ledray, a clinical psychologist, had been prepared to testify that Pulinario was frightened, severely depressed, and suicidal following the rape, and that shooting Santana was a reaction to extreme trauma. But two weeks into the trial, after her lawyer conceded that his client had indeed shot Santana, the district attorney objected to having psychologist Ledray testify.

The trial judge refused to allow this expert testimony as a way of penalizing her for having been untruthful when she had been interviewed by the prosecution’s psychiatrist. She had not disclosed to this psychiatrist that she had had a prior sexual relationship with Santana. (She had disclosed this earlier to officials when reporting the rape).

Federal Judge Weinstein found that this extreme penalty violated Pulinario’s constitutional rights to a fair trial. It prevented Pulinario’s trial counsel, John Ray, from presenting evidence that because of his client’s reaction to the rape she could not have formed the intent to kill, and that, in fear of Santana, she acted in self defense. Ledray would have testified that Pulinario’s conduct including the shooting, her delay in calling the police, the omissions in her statements to the state psychiatrist, her calm demeanor were completely consistent with trauma. The prosecution’s argument that she did not act traumatized was never explained to the jury as being part of the reaction to rape. “The defense was thoroughly sandbagged,” said Barry A. Bohrer, her pro bono counsel, who handled her federal appeal along with David Crow of the Legal Aid Society.

Judge Weinstein wrote, “studies have shown that a rape victim who has a prior sexual relationship with her attacker is less likely to be believed and she may be blamed for having brought the rape upon herself.” If allowed to testify, Ledray would have explained that it is typical of rape victims to blame themselves especially if they know their rapists. Ledray would have testified that it was the defendant’s extreme fear of Santana that caused her to shoot him. The jury would have heard that she lacked criminal responsibility by reason of mental disease or defect or suffered from an extreme emotional disturbance at the time of the shooting, or that she was justified in shooting this man as an act of self defense. The self defense argument was supported by evidence that an open knife was found near Santana’s body.

In addition to omitting the extent of her prior relationship with Santana in her interview with the prosecution’s psychiatrist, the defendant appeared too calm, the prosecution argued, which caused the doctor to conclude that she was a “malingerer,” or not really suffering from an psychiatric problems.

This, Judge Weinstein wrote, “permitted the prosecution to thoroughly exploit the jurors’ misconceptions about the conduct of the rape victim and argue, among other things, that petitioner’s seemingly calm demeanor after the rape and her untruths to the psychiatrist -- which appear to be not untypical of rape victims -- were evidence that she had not been raped.”

No decision has been made on a new trial or an appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit in Foley Square.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice.

Honor Andrew Haswell Green!

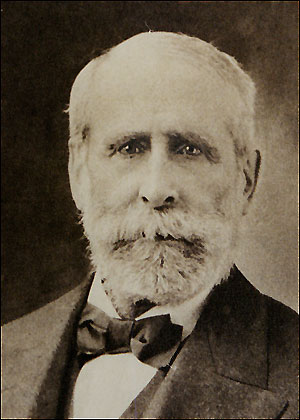

Andrew Haswell Green gets nothing more than a portrait in City Hall and a park bench. |

Exactly one hundred years ago on November 13th, Cornelius Williams, a jealous and delusional furnace tender, set out to kill the elderly gentleman he claimed stole his girlfriend. Williams pumped five bullets into the greatest civic hero in New York City history, 83-year-old Andrew Haswell Green.

New Yorkers can be forgiven for not having heard the name, since his murder is not the only injustice committed against Andrew Green. Obscurity has done in a man whose contributions to the city were truly astonishing.

It was Green who was as much responsible for the creation of Central Park as its architects Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. In his position leading the state commission charged with building the park, he secured the adoption of their Greensward plan, defended it from meddlers, kept it on budget, expanded its acreage.

This would have been enough to make him deserving of recognition, but it is only one of his accomplishments. He was largely responsible for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History. He brokered the creation of the New York Public Library and co-founded the Bronx Zoo. He added Riverside, Morningside and Fort Washington Parks to the map, too, and threw up a bridge over the Harlem River.

Most importantly, Green masterminded the 1898 consolidation of Greater New York, a fiercely contentious measure that, in a stroke, lassoed the various municipalities of today's Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island within the borders of New York City, enlarging the metropolis fivefold.

"It took Robert Moses, Fiorello LaGuardia and Franklin Roosevelt, drawing upon the combined resources of the federal, state and city governments, to exceed Green's accomplishment," urban historian Thomas Kessner has written. But while Moses has a state park, LaGuardia an airport and Roosevelt a drive named after them, among much other recognition, Andrew Haswell Green gets nothing more than a portrait in City Hall and a park bench. He deserves more.

GOTHAM'S FIRST COMPREHENSIVE CITY PLANNER

Born in

New Yorkers can be forgiven for not having heard the name of the man responsible for the Washington Bridge (above) and the Bronx Zoo, since his murder is not the only injustice committed against Andrew Green. New Yorkers can be forgiven for not having heard the name of the man responsible for the Washington Bridge (above) and the Bronx Zoo, since his murder is not the only injustice committed against Andrew Green. |

Worcester, Massachusetts in 1820, Andrew Green moved to New York as a young man, became a lawyer and developed an interest in civic affairs. In 1857, after a stint as president of the Board of Education (where he railed against unfair state funding of upstate schools at the expense of those in the city!) he landed his position on the Central Park Commission. Honest, hardworking and tight with a buck, Green soon became the driving force behind that body

He convinced the legislature to adopt a series of escalating measures that gave the commission authority beyond just Central Park itself, and allowed it to oversee the development of all of northern Manhattan, the Harlem River and the suburban hinterland we now call The Bronx. In essence Green leveraged the Central Park Commission into the first comprehensive urban planning body in New York City history.

Mindful of growth and economy, two principles that would always guide his proposals, Green insisted on the coordinated planning of all the public improvements under his authority -- roadways, parks, bridges, water supplies, transportation lines and even cultural institutions.

By gaining the trust of public officials and the city's powerful business elite with well-formed arguments and a track record to back it up, Green was able to influence the metropolitan region's physical development to the end of the nineteenth century, long after the park commission was officially dissolved in 1870.

COMPTROLLER AND PRESERVATIONIST

In 1871 Green was enlisted to serve as New York City Comptroller after the Tweed Ring bankrupted the municipal treasury. He immediately put a stranglehold on the city's chaotic spending habits. By trimming unneeded workers, denying fraudulent claims, curtailing public works and sometimes even using his own personal credit to secure funds to meet the government payroll, he restored the city's fiscal health.

Green was a lifelong historic preservationist and champion of urban green space. He chose the location of the Bronx Zoo where it would fell the fewest trees, and even objected to the placement of Grant's Tomb and the New York Public Library - an institution he fought hard to create - on park grounds.

Soon after helping to quash a proposal to demolish City Hall and move the seat of government uptown, Green gathered New York's preservationists into the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, an organization he founded in 1895. In his lifetime and beyond the society created numerous state parks, lobbied to save endangered sites like Hamilton Grange, erected countless historic markers and proposed the name for the Williamsburg Bridge.

OUR INDIFFERENT CITY

|

In 1898 a small island was named for Andrew Green at Niagara Falls in recognition of the preservation work he did there. But incredibly, here in the five boroughs, no park, bridge, building, school or even street bears his name! All he has here is a forlorn and obscure bench in Central Park that was evicted from its original prominent hilltop years ago to make room for a compost heap.

"It is preposterous that the only memory marker recalling Green's contributions to New York is a park bench," wrote Mike Wallace, the Pulitzer Prize-winning co-author of Gotham, a History of New York City to 1898.

I agree. And I'd like to propose two significant structures, both in need of a name change, as candidates for a Green monument.

The first is the little-known Washington Bridge, a handsome Harlem River span that Green conceived. Ever since the Port Authority built the giant George Washington Bridge, the name of this other, lesser-known bridge has only confounded drivers.

The other is the Tweed Courthouse, the newly refurbished home of the Department of Education. (Tweed's designation is not "official," some say, but it is literally engraved in stone on the building.) Tweed was perhaps our city's greatest villain and Green our greatest champion; Tweed has a big shiny courthouse, and Green has a sad little bench. Isn't something wrong with this picture?

Michael Miscione discovered Andrew Haswell Green when producing a TV documentary in 1998 about the consolidation of all five boroughs into the City of Greater New York. He has launched a campaign to get a substantial monument named for Green.