Can Small Stores Survive in New York?

With large national chain stores having solidly established themselves in much of the city, Duane Reades and other discount drug stores occupying spaces once used by mom and pop businesses, and banks appearing on every street corner, many locally owned shops have shut their doors. Recently, the Municipal Art Society sponsored a panel discussion on locally owned retail in New York City: Can it survive and what can, or should, be done to save it.

The following comments are excerpted from the discussion.

Creating a Market

By Irwin Cohen

The 8 million people in New York City are being jumped on by the 292 million people who live on the mainland of the United States. They are trying to push their retail ideas on us, and it’s not good. We have to stand up to this, keep our neighborhoods strong and keep merchants in business. But we can do it. The opportunities are unlimited.

Even with the chain stores, you can still go into the retail business and be successful in New York. Maybe we have to cede the rights to have these mall-type stores in Manhattan because, if I’m a landlord and I can get a chain or a bank or a pharmacy to pay a high rent, I would probably think about it. But there are great facilities available in the Bronx and in Brooklyn. There is always something in each neighborhood that is available and can be developed.

You should take some of the parking garages around the city, get rid of them and let the city make that into space exclusively for small businesses. We don’t need cars. We don’t need parking. We have fantastic public transportation. If we got rid of cars and took all the lots and made those into locally owned retail we could go some place. We could set up pushcarts again. We would be healthier, and we would be able to have great shopping.

Chelsea Market

Chelsea Market provides an example of how this can work.

In the middle of the 1990s I was fortunate enough to find the old Nabisco buildings on the West Side. And I was even luckier to have investors in Tashkent, Uzbekistan and in Siberia. When I told them what we had purchased for them in Manhattan, the Russian said, “Aha, the capital of the United States.”

They allowed me to do what I wanted to do with respect to the ground floor of the building. At that time, we would hold meetings, with engineers, architects and construction people. My architect was from Holland. He lived in New York. My structural engineer was from Ireland. He lived in New York. My electrical engineer was form Russia. He lived in New York.

At these meetings, I was the only one who was born in New York City. And I realized one of the great strengths of our five little boroughs is their ethnic diversity. And I said we have to take advantage of that.

And we have to run counter to what everyone else is doing. I was able to convince my investors that just making a lot of money from retailing was not the function of a great, old building of historic significance in New York City. There was something more that the people had to have. So my daughter and I, working together, set some standards.

We said first, every one of our tenants has to be a family owned business, at least half of the businesses have to be female owned, the owner of each business and its executive offices have to be located in Chelsea Market, and the tenants have to be both wholesalers and retailers. That is because when the economy in the city was good, their wholesale business selling to restaurants would be good. But when business slowed down, as it did after 9/11, the tenant could stay in business because their retail operation would cater to the people who were not going out to restaurants.

It was a bit crazy, but it was a social experiment. You have to have a social conscience. But it worked out very, very well.

It was a bit crazy, but it was a social experiment. You have to have a social conscience. But it worked out very, very well.

We have Manhattan Fruit, which did business out of a truck and a very small freezer on 15th Street before it came with us. The Fat Witch Brownies operated from her kitchen. And the man who makes the gift baskets ran his business from his living room.

If you create a market – a concentration of people in similar businesses – you can create stability and establish a location where people will feel comfortable shopping without name stores. Every single tenant in that building that started nine or ten years ago is still there. Our biggest problem is that we don’t have enough room.

The market has to be an experience. At Chelsea Market, you are walking through a street that happens to have a roof on top. I kept it very cool in the winter and warm in the summer because you have to feel as if you’re outside.

We located the tenants haphazardly. Each was chosen for a very, very strong reason. “Can you get what this tenant makes any place else?” And if the answer was no, that was the tenant that we wanted. And that’s why people come back.

We created a neighborhood by having the owners on premises. If you had a little complaint about any of our tenants, they would be in your face in 30 seconds. “You don’t like the recipe? My grandmother used this recipe. She used it in Russia. How can you say it’s no good?” And the owner would take you into her kitchen and show you the ingredients and how she prepares them.

We brought all of the production to the front where people could see it. When we first opened, I could gauge the amount of customer activity and acceptance by the number of nose prints on the glass in front. People would come in with notepads and become specialists in cooking. People come in and watch today the way Amy puts her bread together. And it works.

There was no standard for entrances. I said just keep it clean and decide how you want to run your businesses. The last thing that can fail is where you run your business. You’ll give up your home before you give up your business because you have to eat.

La Marqueta

And there are other opportunities, An example: La Marqueta under the elevated Metro North tracks going up from 111th Street. The state Economic Development Agency said, “Give us some ideas about what we can do to bring La Marqueta back.”

I said, “It’s a good idea, but two blocks of La Marqueta is not the answer. You need a mile of La Marqueta.” And they said, “How are we going to fill it up?”

So, we went into a store on 116th Street where the people were from Senegal. The owner sold leaves that people press at home and use to make tea. And I said, “I have a new business for you. You’ll set up a tea shop and you and all the people that we get into La Marqueta will develop a market – a concentration of wholesalers and retailers.” With that, the owner said something in his language and his entire family came out from behind a curtain – they were living in the store – and one of them said, “I will translate. My father will go to work in La Marqueta and my mother and I will stay here, ”

That’s New York. We can do it.

Hunts Point

I am now working in the South Bronx, in Hunts Point, trying to change the way Hunts Point conduct its retail business. In the next six to a year, you will see what I’m planning to do. We are going to have hundreds of family-owned businesses operating. I’m trying to use that as a model for the rest of the city.

There is plenty of business for everybody. We have many great people in this city who know how to cook and how to sew and how to weave but they don’t have the opportunity to show their wares so they work as bricklayers and they have to work in factories. They could run their own businesses and train their families.

But for it to happen, there have to be people who are willing to take the risks and go against the 292 million people who are generating these malls. It can be done.

--Irwin Cohen is the chief of ATC Management and developed Manhattan’s Chelsea Market.

A Will To Preserve Character

by Victor Dadras

New York City is a city of neighborhoods. We have recognized there is an issue, if not a problem, and that is the loss of the character of those neighborhoods.

Once every neighborhood has the same stores -- Starbucks, Rite Aid, Papa John’s Pizza, and all the others – there is no reason to go from neighborhood to neighborhood. It happens now when you travel. Eat at a TGI Fridays in Salt Lake City, it is like eating at the ones on Long Island. New York City is, along with Boston and Philadelphia, one of the older cities in North America, and we need to be at the forefront of preserving character, which is ultimately what makes people who visit New York come back to shop.

The problem is once you put the independent druggist out of business, where is he coming back from? Once Home Depot and Lowe’s put out the local lumberyard, they’re gone.

We do not have a plan or a vision to address this. The city operates on a reactive basis. Everything we are talking about is a reaction to something that we don’t like, something that is happening to us, to our neighborhood, to the local stores, the corner drugstore, etc.

City property is a perfect example of this lack of vision. City property is always used in my recollection to maximize profit, not to preserve character.

There are many things that can be done. First there must be a will to preserve character. My firm has worked with some communities where people didn’t even think they had a “character.” It was being lost due to ignorance and neglect. So the first thing we need to do is educate communities as to what they actually have. We meet the community and work with them on what they see their neighborhood’s character as being: What do you have? What do you see as the positives, what would you like to improve, how can we best preserve what you have?

But once you have a vision, you develop guidelines. There are certain zoning regulations –- not in New York City -- that prohibit banks on corners. You can have incentive zoning where you try to encourage things or zoning regulations where you discourage things. You cannot tell someone what they can’t do with their property, but you can guide development.

The same criteria Irwin Cohen used for tenants in Chelsea Market can be used by communities, if they are organized, working with the city and the state to help with funding and with regulations and guidelines to help preserve the neighborhood character that makes a place special.

I like the fact that these are independent, hard-working, mom and pop stores and retail that I want to support. That’s why I live in New York.

--Victor Dadras's architecture firm works with neighborhoods to preserve the character of their downtowns and their main streets.

Â

Waterfront In Fits And Starts (And Stops)

If a revitalized waterfront is part of the vision of the current mayoral administration, with projects planned throughout the city, progress has been spotty, beset by squabbles, cost over-runs, reversals or simply inaction. .

Minerva's View

The tale is that the statue of Minerva in Green-Wood Cemetery waves at the State of Liberty in New York Harbor. The nine-foot goddess of wisdom has been sending that greeting since 1920. That's when her bronze form was put up at this highest point in Brooklyn to commemorate a Revolutionary War battle.

When a developer tried to put up a condominium tower at 614 7th Avenue at 23rd Street in Brooklyn that would block the view between the two statues, people in the South Slope neighborhood protested.

At 70 feet, the tower would be taller than the 40 feet the new zoning allowed. But the developer Chaim Mussencweig argued that he had laid the foundation for the building before new zoning went into effect. The tower should be grandfathered in on the old zoning rules.

On September 12, the city Department of Buildings denied his appeal. The building will have to abide by the new zoning rules, and Minerva can keep waving at her big green buddy in the harbor.

It wasn't just for sentiment's sake that neighbors argued to limit the tower. They wanted to maintain a neighborhood of modest-sized residences. Minerva's shield helped win that battle, and now residents have new zoning laws that will keep them safe from marauding high rises.

Belt Parkway Path

After bumping through Brooklyn streets past the hurly burly of apartments and businesses, the Belt Parkway always provides a welcome view of open water and the lofty Verrazano Bridge in the distance. A 13-mile path along the shore to the bridge gives residents of Bay Ridge a place to walk and bike. It was the location for a love scene in an iconic Brooklyn movie, Saturday Night Fever. But like the film, the path shows its age.

The seawall deteriorated badly over the six decades since it was built on landfill, and last summer, the Parks Department closed a two mile stretch of the walkway in order to rebuild it. Cost was estimated at up to $14 million, to be completed by this summer. Complications of backed-up sewers that caused soil erosion delayed the project, now costing more than $20 million and scheduled to be done this month..

Political complications also ensued. Republican Congressman Vito Fossella took credit for getting the project going and for getting $5 million in federal funds.

In a speech in August, his Democratic opponent Steve Harrison said that Fossella waited years too long to spur the repairs, and that he never actually received the federal money. All of the funding came from the parks department.

The issue is likely to remain a factor in the campaign. It'll be worth watching to see each of these candidates for Congress try to prove how much more he cares about a waterfront park than his opponent. Since the city parks department is in charge of the Belt Parkway paths, a Congressional representative won't have much control over the project. But if park advocacy becomes a viable campaign issue, it might be a charming election season in Bay Ridge.

Ikea and the Graving Dock

This isn't a case of paving over paradise and putting in a parking lot, as the lyrics go. It's the case of paving over a gritty piece of Brooklyn's waterfront industry to put up a parking lot.

To some, that might not sound like a bad thing, replacing a noisy, dirty industrial site in Red Hook with a big store that sells good-looking furniture at good prices.

But to some people who work in the waterfront's oldest profession – shipping -- the loss of a graving dock to repair ships is a truly bad idea.

Built in 1867, the dock is a clever structure. A ship floats into the watery parking spot, a door slides shut behind it, and pumps drain the water so that the ship can be repaired. At more than 700 feet, the dry dock can accommodate large ships. Replacing it would cost a fortune.

There's only one other graving dock in the harbor, and it's in New Jersey. Ships go to other ports for maintenance and only use one here for emergency repairs. As more and more ships come into New York Harbor every year, it's shortsighted to fill in a usable graving dock, argues Captain Andy McGovern of the Sandy Hook Pilots Association.

At this point, good arguments for the graving dock's preservation aren't likely to make a difference. The city changed the zoning from manufacturing, and the operator sold the property in early 2005.

Though Ikea is unlikely to take them up on their ideas, the Municipal Art Society offers a plan for accommodating Ikea and their parking needs and preserving the dry dock.

At present, Ikea may leave the outline of the graving dock as a historical relic. Industrial archaeologist Mary Habstritt says that would be like "the outline of a body after a homicide."

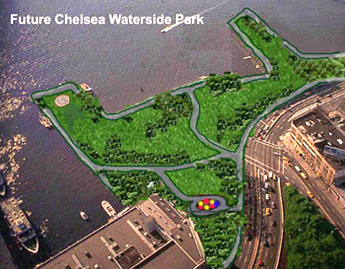

Hudson River Park

Hudson River Park from the Battery to 59th Street features smooth, well-marked walking and bike paths. It's a spine that is being filled out and dressed up with grass, trees, playgrounds, piers with vistas, boathouses, and sports venues. But the park is a work in progress, and the path to completion is not perfectly smooth.

The Hudson River Park Act of 1998 allocated state and city funding ($360 million so far) to remake the five-mile-long park from a stretch of derelict piers into a waterfront showplace. By rebuilding 13 piers, the plan respects the historic importance of the working waterfront.

Today, the completed sections show off lush lawns, pleasant playgrounds, and spacious piers.

The section adjacent to Greenwich Village opened in 2003. Clinton Cove Park at 54th Street opened last spring. A newly landscaped park and walkway opened in July from Battery Place (the west end of Battery Park) to Chambers Street. In mid-October, Pier 84 at 42nd Street (next to The Intrepid, the museum battleship) will open, becoming the largest public pier in Manhattan. It will feature a boathouse and a large fountain.

Work recently started on sections across from Tribeca and Chelsea. Two new piers will offer spectacular views. These are not quick projects. They should be ready by 2009.

There are growing pains. Pier 63 in Chelsea will be demolished and rebuilt as a public space. In order to start the work, The Hudson River Trust, which runs the park, evicted the commercial enterprises there.

Basketball City, which occupied Pier 63 for nine years, fought eviction. Legal appeals gave them several reprieves over the years. But they lost their last appeal in August and had to vacate the pier by September 10.

Sixteen high schools from around the city and corporate leagues rented space in the six courts of the for-profit courts. Now Basketball City is scrambling for temporary space.

Another venture at Pier 63 knew that demolition was coming, but was still unprepared. When the Manhattan Kayak Company www.manhattankayak.com had to vacate the pier on September 10, it seemed to cut the boating season cruelly short. They had counted on Basketball City prevailing again, and they thought that the trust wouldn't throw them out so quickly.

The kayak company co-owner was philosophical about it: "The suddenness of this came as a bit of shock to us all as you may imagine, but we must adapt and continue as we always do," wrote Eric Stiller on the company's Web site.

In the meantime, the kayak company will work from the boathouse at Pier 96 (at 57th Street). Next year, the company will run their operation from 26th Street.

The pier also houses the New York Police Department's mounted unit, which will move its stables to another pier.

Lower East Side

Basketball City eventually plans to move to a pier on the East River just north of the Manhattan Bridge, one of three piers on the Lower East that are scheduled to be refurbished and opened to the public. The piers are currently behind tall chain-link fences.

Re-using the piers for new purposes is part of a larger plan to fix up the walkway/bikeway under the FDR drive adjacent to the Financial District, Chinatown and the Lower East Side. There is a biking and walking path under the FDR with glorious views of the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, but beneath the highway next to the promenade along the river are parking lots, bad lighting and noise.

Funding for beautification is already there, in part from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (from federal funding allocated in the aftermath of the attacks on the World Trade Center). The work has yet to begin, however.

City Councilmember Alan Gerson, who represents the area, says he's looking for an expedited timetable for the entire waterfront project along the East River. "We should be making better progress," he says. "We should not be going through 'hurry up and wait.'"

East River Park

Just north of the Manhattan Bridge, the park is still a mess, though rebuilding started on the walkway along the river last year. After contractors tore out the old promenade, soil from the muddy embankment began sliding into the river. The contractors placed bales of straw to stop the churned up mud from further erosion.

The work then stopped. Most of this summer, the construction site looked deserted, with heavy machinery sitting idle. Now, a parks department spokesman promises it will resume.

The delay did not attract much complaint from the neighborhood. The walkway has been closed since 2001, when it was deemed unsafe, so the community is used to living without it.

Carter Craft of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance thinks the lack of community outrage at the stalled rebuilding has to do with how cut off the neighborhood is from the river on the Lower East Side. "They're so used to having crappy access," he says. He notes that there are just three pedestrian bridges across the FDR Drive to the park.

If construction stopped on the West side, where access is plentiful, says Craft, "they'd go nuts.”

Some on the Lower East Side explain the reaction differently. "The kind of development that happened on the West Side is the kind of development that’s going to raise rents and the cost of living, and I think there’s a huge part of this neighborhood that’s very scared of that," said David McWater, chair of Community Board 3 in Grand Street News, a neighborhood magazine. "They’d rather leave it alone because we don’t want everybody wanting to move here, because then I’m going to have to move to Iowa."

A Faster Track

The delay in the promenade construction led at least to one unexpected benefit. Since the landscapers couldn't work on the promenade, they transferred their energies to a runners’ track in the park at 6th Street. Runners will have their place to train in service at the end of September, well ahead of schedule.

Â

Housing Activists' Fall Agenda

While the scarcity of affordable housing continues to grab most of the attention when people talk about housing issues, advocates are pushing for answers to other problems. They have a full agenda for the fall, some of it a continuation of battles already begun – one is against the city’s flawed rent subsidy program, little more than a year old, called Housing Stability Plus, another is the effort to repeal the Urstadt Law, which prevents the City Council from strengthening rent regulation laws that affect about one million apartments in the city.

Building on the momentum housing issues have gained politically over the last year, though, advocates are now mounting new campaigns. In coming months some are hoping to persuade the City Council to pass legislation that would:

- Establish a “repair board” to enforce the city’s housing maintenance code

- Establish the right to counsel for senior citizens in housing court

- Make it illegal to discriminate against a person because of her or his source of income under the city’s human rights law

- Make it possible for tenants to sue landlords for harassment in housing court

Few advocates pretend that any of these issues will be easy to achieve. They are building support among a wide variety of groups for the inevitable political fights ahead.

Repair Board

For months John Williams has been trying to get his landlord to remedy a mold problem that is turning the floor of his Brooklyn apartment black. A tenant for 26 years who has always paid his rent, Williams has a problem that is far from unique in New York. Repair problems are as common in the city as cockroaches, which themselves are a problem that landlords are obligated to “repair” under the city’s Housing Maintenance Code.

When a tenant reports a problem to the city, an inspector is sent to confirm a violation of the housing code. That violation is entered in the Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s computer database and the landlord is then informed. And that’s usually where it stops. The exception is when the tenant – or the city’s housing department -- starts a lawsuit against the landlord in housing court.

“The current system isn’t working,” argues Ben Dulchin of Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development, which has spearheaded a campaign to make violations of the housing code like violations of the building code or the traffic code: Inspectors would be writing tickets and landlords would have to appeal to a newly created repair board, which would be an administrative tribunal.

“Just look at the statistics, Dulchin said. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development “writes 400,000 violations a year. About 25 percent are heard by a judge in housing court and most of those get corrected. But the other 75 percent are dealt with by sending a notice of violation … a polite suggestion to the landlord” to make a repair. “There is a misconception that notices of violation have teeth. They don’t.”

This explains why the city’s computers contain a list of three million housing code violations reported but never resolved.

The idea of a repair board has been around since the early 1980s, but got a boost recently when Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, the Democratic candidate for governor, expressed his support for its creation.

Landlords generally do not like this idea: “Anyone who thinks that penalizing the landlord is going to make more money available for repairs is fooling themselves,” said one landlord who asked to remain anonymous because he deals frequently with government agencies. “It’s going to mean less money for repairs.”

But some tenant attorneys feel the same way. The remedy a repair board offers “is not repairs; it’s fines,” said Susan Cohen, an attorney at MFY Legal Services. “The fine will be a cost of doing business. An administrative tribunal would have no authority to order repairs. It would just levy fines.”

Right To Counsel For Low-Income Senior Citizens

Of all the problems in housing court, none strikes more people as less fair than the uneven distribution of attorneys. While almost all landlords have legal representation, almost no tenants do. Free legal services available in the city are woefully under-funded and can represent only a small fraction of the people who qualify for their services.

For more than two decades advocates have sought to establish a right to counsel at housing court to remedy this problem. A small step in that direction is now under consideration: Establishing a right to counsel for low-income senior citizens in housing court.

“Housing laws in New York are very complex and on top of that the court system is difficult to navigate,” said Craig Acorn of the Community Service Society, one of the organizations pushing the proposal. “People who are brought to court on eviction actions are often very intimidated by those two things…. And landlords have an unfair advantage over those who are un-represented.”

Landlords have long opposed a right to counsel in housing court, arguing that giving tenants attorneys would be too expensive and slow down eviction proceedings. The court, they say, would need more judges, court personnel and space.

Acorn argues that the costs would be less than they are now. Evictions are expensive: “People who get evicted – in inordinate numbers elderly people – end up in nursing homes, hospitals, shelters,” he said. “One way or another, the city and state become responsible for their care. “And there’s an intangible benefit [to preventing their evictions] because we think that maintaining the character of a community and a neighborhood in large part depends on allowing long-term residents to stay where they’ve lived for years.”

Income Discrimination

The city’s human rights law, among the most comprehensive in the nation, outlaws discrimination in housing for a number of “protected classes.” One reason advocates say tenants are being forced out of affordable housing is landlords’ refusal to accept rent subsidies like Section 8 and public assistance. The answer is to update the city’s human rights law to prohibit discrimination based on “source of income.”

“It has become a very frightening way to push out long-term residents,” said Anne Lessy of the Pratt Area Community Council in Brooklyn. “Landlords are refusing to renew leases for tenants with Section 8 or other subsidies. And it’s harder for people to identify new housing opportunities if they receive income support or other assistance.”

The City Council is now considering legislation that would add source of income to the list of protected classes under the city’s human rights law.

The same landlord who cringed at the thought of a repair board was apoplectic at the thought of being forced to accept Section 8 and other rent subsidies: “The government behaves horribly in those programs,” he said. “I’ve had hundreds of bad situations. The city would be two years behind in paying. The city takes two years to figure out (a rent increase) and I’m supposed to go back and whack this tenant for two years rent?”

In fact, whether landlords should have to accept Section 8 in rent stabilized apartments – where leases automatically renew under “the same terms and conditions as the original lease” – has been a source of contention between landlords and tenants for a few years now. An appeals court decision is expected before the end of the year on this issue because housing court judges have come down on both sides.

But Lessy pointed out that other cities around the country have expanded their human rights laws to prohibit discrimination based on where their money is coming from.The answer to inefficient bureaucracies is not discrimination; the answer is to fix the bureaucracy, she said.

Suing For Harassment

When he was an organizer at the Fifth Avenue Committee in Brooklyn, Ben Dulchin recalls a landlord who put a bomb in the lobby of a building. The tenants filed an harassment complaint with the state’s Division of Housing and Community Renewal, which oversees rent regulated apartments.

“But (the division) said because he only planted one bomb, it wasn’t harassment,” Dulchin recalled. “Harassment, they said, was a pattern of behavior. That was the last time I filed an harassment claim with DHCR.” Dulchin is hoping the City Council will make harassment a “right of action” for tenants at housing court, allowing them the possibility of counter-suing when landlords file frivolous cases. Again, because landlords are almost always represented by attorneys, they do not have to go to housing court themselves. Most tenants do not get attorneys and end up spending hours at court, often losing at least a day’s pay as a result.

“We get calls from people who have been taken to court even though they’ve paid the rent,” said Jenny Laurie of the Met Council on Housing. “Some mechanism for getting landlords to stop suing tenants just to harass them would be good.”

It is not clear what punishments landlords would face for filing frivolous cases. But giving tenants the power to counter-sue for harassment would be a powerful deterrent against hauling tenants into court for rent that’s already been paid or subletting their apartments when all they have done is found a roommate.

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations. Â

Housing In New York City -- Figuring Out The Big (And Little) Picture

When Metropolitan Life recently announced plans to sell Peter Cooper Village and Stuyvesant Town - two communities the insurance company built a half century ago to house the middle class - many New Yorkers wondered whether the residents would soon be priced out of their homes: "The city can't survive without middle-class housing," Senator Charles Schumer said at a press conference to save the two housing complexesfor the middle class. But a new report shows that the residents of an area that includes Stuyvesant Town already have the highest median income of any community in the city.

When Metropolitan Life recently announced plans to sell Peter Cooper Village and Stuyvesant Town - two communities the insurance company built a half century ago to house the middle class - many New Yorkers wondered whether the residents would soon be priced out of their homes: "The city can't survive without middle-class housing," Senator Charles Schumer said at a press conference to save the two housing complexesfor the middle class. But a new report shows that the residents of an area that includes Stuyvesant Town already have the highest median income of any community in the city.

In the area with the second lowest median income in the city, Morrisania-Crotona in the Bronx, according to that same report produced by the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy at NYU, there are high rates of crime and poverty, and low student test scores, but nevertheless the price of housing in the area is on the rise, more people are purchasing homes there, and more homes are being built.

|

Median Income:

|

As New Yorkers obsess about real estate - some struggling to find a place to live, others worried about staving off eviction, still others hoping to get rich off the market - they all think they know what is going on in the housing market: Housing is scarce and expensive. But the picture is complicated, playing out differently in different neighborhoods, and the effect of the situation varies from community to community, as do the reactions to it.

So how does one get a good picture of what's going on?

City Hall released the latest Mayor's Management Reportlate last week, a legally-required document that the Bloomberg administration touts as "a public report card on city services affecting the lives of New Yorkers," but which critics see as a missed opportunity to help citizens piece together a picture of the state of the city, issue by issue, including housing.

The accompanying report put out by the Mayor's Office of Operations, however -- the online service My Neighborhood Statistics -- provides information broken down by community, and now features the latest data, from the fiscal year that ended this summer. Other reports, some by city agencies, others by private organizations, offer a closer and often more nuanced look at one of the issues of greatest concern to New Yorkers, the city's housing. There are surprises in these figures, but even more mysteries.

WHAT THE FIGURES SHOW

More Housing

The city now issues about 20,000 building permits a year, up from an average of 7,000 in the 1990s. "And the increase is not just in Manhattan," says the Furman center's director Vicki Been. "When we had something of a boom in the 1980s, it was concentrated in Manhattan and a few parts of Brooklyn. But now, perhaps because the improvement in the city has lasted longer, there has been a real shift."

|

Racial Diversity:

|

While the neighborhoods that had the most new permits issued in 2004 - Clinton-Chelsea and the Upper East Side - are in Manhattan, the number three neighborhood is Rockaway-Broad Channel at the southern edge of Queens, where 886 permits were issued in 2004.

Much available housing is for sale (rather than for rent) and at high prices, judging from information gathered by the real estate broker Prudential Douglas Elliman , which reports that there has been a 53.9 percent increase this year over the same period last year in the number of condos and co-ops on the market in Manhattan. These are both new apartments and those being re-sold.

What about affordable housing? The latest Mayor's Management Report notes progress in Bloomberg's 10-year New Housing Marketplace Plan, having started to build or preserve 17,393 homes in the fiscal year that ended in June. The program also financed or otherwise helped complete more than 13,000 homes. To further increase the supply of affordable housing, the report also points out the administration's approval of new "inclusionary zoning" - one for a site on the Williamsburg waterfront, the other for Queens Boulevard in Maspeth-Woodside -- that allows private developers to build taller buildings if they provide affordable apartments.

But City Hall has also taken steps to slow down construction of new housing in some neighborhoods, those that complain of overdevelopment, by rezoning to allow for less density (known as downzoning) in 20 neighborhoods last year. The Bloomberg administration expects to do this in other communities in the future, according to the Mayor's Management Report.

Meanwhile, rising interest rates, and higher costs for some building products and oil, could discourage new construction in the future -- or push the prices for housing even higher.

More Expensive Housing

|

Permits for New Homes

|

What housing there is in New York City -- houses and apartments, rentals as well as coops and condominiums -- continues to grow more costly.

In the city as a whole, the cost of a dwelling with two to four families has almost doubled since 1994, with Fort Greene-Brooklyn Heights seeing the biggest increase, according to the Furman Center report. The median price of a condo in the city rose by 12 percent from 2002 to 2003, with the largest increase in Chelsea/Clinton. The median monthly rent for unsubsidized housing increased from $831 in 2002 to $900 in 2005 (in constant dollars). While the greatest jump came in the area grouped together as Greenwich Village-Financial District, poor neighborhoods are seeing price increases too. In Morrisania-Crotona, home prices went up by almost 50 percent between 2002 and 2004.

The city government is feeling the effects of the housing inflation as well, according to the Mayors Management Report. Its spending on public housing has increased every year since 2002, and the cost of providing homeless shelter facilities has gone up.

|

Crowded Households

|

And the increases continue, despite talk of a softening real estate market. At the upper end of the housing chain, Prudential Douglas Elliman found that the average sale price of a Manhattan residence increased by more than five percent between the second quarter of 2005 and 2006.

The Housing Gap

The city continues to lose low and moderate income housing. "We're losing more at one end than we're gaining in affordable housing at the other end through the mayor's plan," Victor Bach, a senior policy analyst for the Community Service Society, told the New York Times recently. "It's more difficult to make the argument that the efforts of the city in affordable housing, which deserve a lot of praise, are going to compensate for the market losses that occur through sales."

In 2005, city residents needed 100,000 more homes than existed in the city, the Furman Center estimates. And the city planning department Housing Consolidation report for 2005 found that in 1999 (the year it cites in the report) only 3.19 percent of the city's rental housing was vacant - well below the 5 percent rate considered the threshold for a "housing emergency."

As further evidence of the shortage, the Mayors Management Report says that the building department responded to 25 percent more complaints about illegal conversions of residential space.

Given the rules of supply and demand, such a shortage has pushed rents and purchase prices higher. But while housing costs have risen, New Yorkers' incomes have not. The median household income in the city actually declined in constant dollars between 2002 and 2005 - from $42,700 to $40,000. And in 35 of the city's neighborhoods, the poverty rate increased. According to the American Community Survey - which is available on the city planning department web site - more than 23 percent of city families with children under 18 have incomes below the poverty line.

|

Median Rent

|

A general rule of thumb is that people should spend about 30 percent of their income on housing and utilities. By this measure, the Furman Center calculates, a family making $32,000 should pay no more than $800 a month on housing. But between 2002 and 2005, the number of apartments that that family could afford decreased by 205,000 homes.

Experts generally agree that the housing crunch in New York contributes to the number of homeless people. But, in the Mayors Management Report, Bloomberg says that the estimated number of homeless people living on the streets, in parks, under highways, and public fell by 13 percent - from 4,395 in fiscal 2005 to 3,843 in fiscal 2006. Advocates for the homeless, however, have disputed the accuracy of these numbers.

Better Neighborhoods, Costlier Neighborhoods

Depending on whom you ask, the housing situation offers a kind of good news/bad news dilemma in many communities. Falling crime rates have made previously depressed neighborhoods, such as East New York and parts of the South Bronx, more attractive places to live. And this has boosted costs.

The Mayors Management Report cites an array of improvements in services from a decrease in crime to cleaner street to smaller class sizes in the public schools. "Two-thirds of the things are going in the right direction," Bloomberg said upon releasing the annual audit. "A third aren't going as fast as I'd like, or in the right direction."

By going to My Neighborhood statistics, people can chart the improvement or decline in city services in their neighborhood, as defined by community district. Going to the pages for the Bushwick section of Brooklyn, for example, one sees that the area's streets have become appreciably cleaner since 2002 while parks have grown dirtier. Crime has gone down in most categories, while schools are less crowded.

But perusing the Furman report makes it clear that Bushwick is not any easier to figure out than many communities in the city. Even though Bushwick has the fewest number of places to live, and has the highest number of serious housing code violations, it also has the highest number of mortgages being taken out -- and among the highest notices of foreclosures.

GETTING THE NUMBERS

|

Vacancy Rate for Rental Housing

|

Any number of agencies, organizations and others compile number of the city's housing situation. Some offer a kind of consumer help - where would you like to live - others advance a political agenda and still others have more of a policy focus.

Mayor's Management Report

The city charter requires that the mayor issue two management reports a year: a preliminary report by mid-January and a final report by mid-September. The report for fiscal year 2006 was released last week with little fanfare - there was virtually no advance warning and the mayor did not offer visual aids or the general hoopla he has at times in the past.

The report assesses whether city agencies have met goals in a number of different areas. Housing information can be found in the sections for the departments of Housing Preservation and Development, Homeless Services and City Planning.

But by its focus on specifics, the report makes it difficult to glean information on big city problems. For example, the advances in providing affordable housing are concealed in two dry paragraphs about the New Housing Marketplace Program.

"It includes too many insignificant indicators, lacks any overview or sense of priorities, and says little or nothing about such major (and problematic) policies as the reorganization of city schools, big changes in homeless services, the costs of school construction, and high levels of overtime among the city's uniformed services, " Glenn Pasanen wrote in Gotham Gazette assessing last year's report.

My Neighborhood Statistics

Compiled by the Mayor's Office of Operations, this accessible program provides information about city neighborhoods as defined by community board. One types in an address (or an intersection) to get to an array of information, including complaints to the city's 311 line, health and education data, information about the condition of area parks and streets, crime and figures

The site takes data from city agencies, so there is no information on rents (since that is charged by private landlords) but there is data on housing complaints. Much of the data is raw - one sees the number of felonies in the neighborhood but it is not ranked or given as a rate so that people can easily compare one community with another.

City Planning Department

The city planning department offers a number of reference tools on its site:

|

Serious Housing Code Violation

|

New York City Census Fact Finder: The planning department's home page features a "GeoQuery" box. Typing in an address brings you to a map, showing the census tract and the adjoining area, and to tables with a lot of information from the 2000 census. Two pages focus on housing - one on characteristics, including vacancy rates, types of housing and so on; the other looks at costs.

The tool allows users to create the boundaries of their own neighborhood, combining adjoining census tracts and to get statistics on that area

In the case of Stuyvesant Town for example, one can focus on its census tracts from 14th to 23rd Street, rather than on the whole swath of the East Side up to 59th Street that comprises the community district. While the more tightly defined area is hardly poor, in 2000, more than two thirds of its households had incomes of less than $100,000 - bolstering claims of its middle class character.

Community District Profiles: These are portraits - each about 35 pages long - of each community district in the city, based on the 2000 census and broken it down by census tract. Some information is updated to 2003; other charts compare the figures for 1990 and 2000. It also lists community facilities - such as schools, libraries and hospital.

American Community Survey: This is essentially a 2005 update of the 2000 census, providing information for community districts with at least 100,000 people.

City Planning Commission Reports: In addition to providing a sense of what a neighborhood is like now, the site also offers links to reports on how the area might change. Visitors can search the commission reports section by borough, type , date and perhaps most conveniently by keyword. Typing in Williamsburg and inclusionary, for example, produces the report the commission report on allowing a 20 percent taller building

New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey

The city housing department produces this every few years. Its primary goal is to get information that can be used to evaluate rent control and rent stabilization laws, but the survey also includes a range of demographic and other information that can be used to help set housing policy. To gather this data, an adult in each of about 18,000 homes is asked a series of questions focusing on housing and its cost - the utility bill, whether an apartment is wheelchair accessible, if rodents are a problem and so on. The tables provide a wealth of raw statistical information but the report, published on the U.S. Census Bureau web site, but does not analyze the material on the site.

State of New York City's Housing and Neighborhoods

|

Number of Places to Live

|

The Furman Center does analyze much of the data from the housing and vacancy survey, along with material from the city finance department and other sources, and puts it on its New York City Housing and Information system that offers information for the city as a whole and by borough and community district. They boil this down into the State of New York City's Housing and Neighborhoods-- available in hard copy and online -- that shows how each of the city's communities has been changing over the past four years and compares community districts, by ranking them on a number of indicators. It also interprets the data in interesting ways, devising, for example, an indicator of racial diversity and of income diversity.

Community groups use this data to address issues in their communities, such sa so-called predatory lending -- housing loans with excessively high interest rates or fraudulent terms. Groups working to address housing code enforcement - a key fight for many housing activists this year -- have also used it. (See related story, Housing Activists' Fall Agenda.)

Market Reports

Produced by the real estate company Prudential Douglas Elliman, these reports offer a very different perspective on the housing market, surveying the market for homes in Manhattan - loft, coops, condominiums, etc. They are the source of those stories, so beloved by the New York Times, of average home prices going above the $1 million mark.Â

Inclusionary Zoning

City Hall has encouraged affordable housing in Manhattan for decades by the use of an innovative land use tool known as inclusionary zoning. This allows real estate developers to construct bigger buildings in exchange for allocating a portion of the new housing to people with modest incomes. Such measures were incorporated in the recent rezoning of Manhattan’s West Side.

This practice was extended to Brooklyn in June, when ground was broken at 164 Kent Avenue, an apartment building that will include 113 apartments for people of moderate income. Now it has come as well to one area in Queens, sections of Queens Boulevard in Woodside.

While the loudest voices in many local zoning battles in Queens have often been homeowners and neighborhood associations seeking to restrict real estate development, this time housing advocates played a prominent role in steering new private development in a way that insures some affordable housing.

Inclusionary zoning is also being considered in several other neighborhoods where zoning changes are proposed that would spur new development. In other words, it has now become an accepted norm throughout the city

The Turnaround in City Policy

Only a few years ago, affordable housing advocates were criticizing the administration for refusing to use this land use tool outside the sections of Manhattan where they have been in place for years. The City Planning Department refused to incorporate in the rezoning of Fourth Avenue in Brooklyn, for example, much to the chagrin of local housing groups that were concerned that the city’s zoning would displace low-income households. The city’s planners argued that it was too cumbersome and wouldn’t work, and pointed to the relatively low numbers of affordable units created under the complex rules used in Manhattan.

Housing advocates made their case for a change in policy to candidates in the 2005 election campaign, and mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer came out with a strong platform calling for inclusionary zoning and other measures to beef up the city’s programs for low- and moderate-income housing. In October, Mayor Michael Bloomberg countered by expanding the scope of his long-term housing plan and for the first time endorsed inclusionary zoning.

Pitfalls

Are we looking at a new day for land use policy, where a hot real estate market will also mean more housing to stem the growing deficit in affordable units for people who can’t afford market-rate housing? Do we have the perfect “win-win” situation where both private developers and low-income people come out ahead?

Perhaps it’s too early for housing advocates to break out the champagne. Here’s why:

- Inclusionary zoning in New York City is voluntary and not mandatory. The incentives may or may not be used, and it is strictly at the discretion of the private developer. There are scores of similar zoning practices around the country, some in big cities, but they only produce a good number of units of housing where it is a requirement and not an option. Developers simply incorporate it in their business plans (and with generous subsidies they can end up coming out ahead of the game), and mandatory rules affect every developer equally. Maybe a mandatory rule ought to be the next step here?

- Right now the rules have to be established on a case-by-case basis and only when there’s a rezoning proposal put in front of community groups. Housing advocates have their work cut out for them if they want to win such zoning in all developing neighborhoods; they will have to win many separate battles, one at a time. The result may end up being the concentration of new affordable housing in only a small number of neighborhoods where there happens to be a receptive political climate and where housing advocates can muster enough muscle.

- Areas of the city that lack developer interest and where the city’s planners aren’t interested in rezoning will be left behind. Because inclusionary zoning relies on market-rate development, what happens when the market collapses or dissipates? What about the neighborhoods with chronically weak developer interest? Will they be left out?

- It’s easy to forget that 80 percent of the housing created under inclusionary zoning rents at whatever the market can bear. When this new market-rate housing moves into neighborhoods with relatively affordable homes it can jack up rents and housing prices and have a net effect of displacing more low-income people than it provides housing for.

- This kind of housing is usually not available to very low-income households, but tends to serve households with higher incomes. In some cases they can be built off-site, in which case they could help create less integrated neighborhoods.

These are all reasons for caution, but not cause for abandoning the concept.

“Inclusionary zoning has to be one among many tools for affordable housing,” according to Benjamin Dulchin, director of the Initiative for Neighborhood and City-wide Organizing at the Association of Neighborhood Housing Developers (http://www.anhd.org/) in New York. “It can help harness the private sector but it doesn’t let government off the hook.” There are four things that government can do now to promote affordable housing, says Dulchin. They need to:

- invest in new development

- preserve existing affordable units

- protect subsidy programs that may expire

- and secure rent regulations.

This brings us back to the main purpose of inclusionary zoning. If the purpose is only to produce housing units, it may not have the numbers to show, and it could even backfire if it serves as a cover for market-driven displacement. The political impetus for such zoning in the suburbs was to open up housing markets that were exclusionary. The impetus for such zoning in New York is mostly to protect affordable neighborhoods, and not just to produce new affordable housing.

So the final question is an open one to the scores of non-profit housing developers in the city. You are the only neighborhood-based developers with a long-term commitment to not only create affordable units but make neighborhoods strong by insuring jobs, services and greater equity. How about a program that works the other way around: 20 percent market-rate and 80 percent affordable?

The best and most comprehensive case for inclusionary zoning in New York is “Increasing Housing Opportunities in New York City: The Case for Inclusionary Zoning,”issued in 2004 by the Pratt Institute Center for Community & Environmental Development and PolicyLink. The report includes the recommendation for mandatory rules and other proposals that would help the city move towards a more effective inclusionary housing policy. Before the next neighborhood battle, it might be worth dusting it off and thinking more about where we’re going.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â

9/11 + 5

Covered completely in ash from the collapse of the twin towers, the clothes in Chelsea Jeans in lower Manhattan remained in the store window for 13 months after 9/11, presented and preserved by David Cohen, the store's owner. In October 2002, his display was packed into hermetically sealed crates. Now the crates have been unsealed and the scene recreated, literally, as a museum piece. They are now on display in a glass case next to the cafeteria in the basement of the New York Historical Society.

New Yorkers are preparing to mark the fifth anniversary of September 11. There are exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum and the Police Museum, retrospective panel discussions, a new movie and a new book that promised to stir up controversy, and a day of commemoration planned for Ground Zero itself, ending with the Tribute in Light, an art installation intended to be a one-time deal that has morphed into a periodic memorial

The permanent memorial, meanwhile, is still a series of architectural drawings.

Like previous anniversaries, the fifth anniversary will undoubtedly inspire not only reflection on the attacks but also on the progress that has been made in rebuilding the city. This September 11, though, there is little to mark except the passing of time. Ground Zero looks more or less what it looked like on its fourth birthday or, for that matter, its third. The general public is no longer following the debate what the memorial should look like, or what kind of retail stores should go there. The agency in charge of coordinating the rebuilding of the site – the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation – says it is "nearing the end of [its] mission", and had declared itself defunct.

Many of those involved say that the progress continues, even if it isn’t visible to the naked eye. The transportation hub, which has always been immune to the vitriol and stagnation of the memorial and the Freedom Tower, remains on schedule. Designs for the remaining three towers will be unveiled this week, the first time that plans for the entire site will be made public. The change in administration in Albany, many believe, will push forward turning this plan into actual buildings.

Each reassurance, though, seems to carry less weight with New Yorkers who marked the “symbolic beginning” of the construction at Ground Zero – the laying of the cornerstone of the Freedom Tower – over two years ago. This summer, the cornerstone was actually removed from Ground Zero, as newfound concerns about where on the site the Freedom Tower should be built arose. It has not returned.

When construction will be completed, or what, exactly, will be built are still open questions. Meanwhile the pain from the attacks themselves has been dulled by another passing year. Have we gotten over it?

"I think people are sick of hearing about closure," said Amy Weinstein, the curator of Elegy in the Dust, the exhibit at the New York Historical Society. "But I think that with the passage of time, things have changed. People have some perspective, a little distance, or a measured appreciation for how their lives have changed."

Investigative reporter Wayne Barrett believes that time has healed the pain enough to raise questions that would have been taboo in years past. His new book Grand Illusion questions former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's legacy as a 9/11 hero; in a recent interview he said he has long had the material to write the book, but held off until he and his publishers thought people would be ready.

"There had to be an adjustment period," he said.

For those most affected by the attacks – those who lost loved ones, those who are getting sick from exposure to the chemicals released in the buildings’ collapse, and those who live and work in the immediate area – life didn’t return to what it was before 9/11. Cohen of Chelsea Jeans, for example, watched as his store went out of business as downtown's economy dried up after 9/11. He moved his family out of the city he had immigrated to almost twenty years earlier, and started over in Florida.

FIVE YEARS LATER

Life in the city is different than it was before 9/11. In some ways, the changes are subtle, or have been internalized. In others, it remains unclear how the aftermath of 9/11 will play out years from now.

Life in the city is different than it was before 9/11. In some ways, the changes are subtle, or have been internalized. In others, it remains unclear how the aftermath of 9/11 will play out years from now.

Security: The single factor that has changed the everyday life of New Yorkers more than anything else since 9/11 is the increase in security.

The most visible tightening is at the airports and in the air. But there is a greater police presence on the ground, and underground. Bags on the subways are searched randomly. Earlier this year the police department announced that it would establish a "ring of steel" around lower Manhattan, recording every person or vehicle to go south of Chambers Street. The project has been put on hold because of a reduction in anti-terrorism funding – an issue that has suddenly become a constant source of tension between New York and the federal government – but aggressive surveillance measures continue to be put in place by the government and by private businesses.

The Partnership for New York City, a business group representing major employers, recently surveyed its members, finding that their costs for security have risen between 10 and 20 percent, well over the average increase nationwide. Insurance costs for companies operating in New York have also spiked.

There is a social price as well, says Donna Lieberman of the New York Civil Liberties Union, which is concerned about the city's willingness to subvert personal liberties for security. Often, the threat of terrorism is being used to monitor legal political activities in ways that would have been unacceptable before 9/11.

"When you don't feel the pain immediately, you don't notice the problem," she said. "It's very, very difficult to reverse practices like this."

Health: For years, officials have questioned whether there is a direct link between certain illnesses and exposure to chemicals released in the collapse of the Twin Towers. But just last week, the city sent guidelines to doctors for identifying illnesses related to 9/11. The state also recently passed a law giving more generous benefits to rescue workers whose illnesses seem 9/11-related.

The toll that 9/11 will eventually take on the health of those who worked on the rescue effort – or those who simply lived nearby – will likely continue for many years. But critics still say that there has been a failure to take responsibility for such sicknesses at all levels of government.

Economic Development: The aftermath of the attacks doomed individual businesses, like Chelsea Jeans or small manufacturers in Chinatown, who always operated on thin margins. But industries whose outcomes looked bleak several years ago are no longer struggling. Restaurants, tourism and retail, and the airline industry are operating at or above levels they were before 9/11. In fiscal 2006, the city's gross domestic product, a measure the comptroller's office uses to measure the city's overall economic output, surpassed its pre 9/11 peak for the first time since the attacks.

Some things, however, have changed.

Companies are also more apt for spread their operations geographically, instead of concentrating them in Manhattan. This, along with national economic trends, means that there are seven percent fewer finance jobs now than before the attacks, according to Kathryn Wylde, head of the Partnership for New York City.

Businesses want to ensure that they no longer rely solely on a single geographic location, she said, and have moved some operations out of New York as a result.

"That's probably a permanent dislocation."

REBUILDING LOWER MANHATTAN

The physical rebuilding of lower Manhattan – a project that gripped the attention of the city in a way unlike any before or since – has faded from the daily news. But what happens at Ground Zero remains vitally important for the city's economic – and emotional – recovery.

Lower Manhattan, says Wylde, has about 28,000 fewer jobs than it did before 9/11. This is roughly the number of people who worked at the World Trade Center, and "for obvious reasons, those jobs aren't back," she said.

Wylde and others see positive signs for the development of Ground Zero, but acknowledge that the project remains beset by frustration.

Positive Signs

Transportation Infrastructure: The one piece of the plan for Ground Zero that has moved smoothly is the transportation hub, designed by renowned architect Santiago Calatrava. A temporary PATH station already exists on the site, and is scheduled to be replaced by 2009.

One block away, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority is working on a new $750 million Fulton Street subway station. Critics have called the project unnecessary, but others say it will make the area a more attractive place to the businesses that will hopefully move into the offices at Ground Zero. It appears to be moving ahead on schedule.

"You have to realize the tremendous capital expenditure that's being made downtown to rebuild transportation, communication," said Brian Weld of Colliers ABR, a real estate firm. "The basic nuts and bolts of downtown are being entirely rebuilt."

A Better Business Climate? Even with improved transportation to the area, there have long been doubts that the commercial real estate market in New York could handle much new office space. There are signs today, however, that new office buildings would do well.

Demand for new office space is strong. Vacancy rates are falling, and rents rising. Much of what is available downtown is in older buildings without large blocks of space. Many feel it seems ready for new buildings.

Demand for new office space is strong. Vacancy rates are falling, and rents rising. Much of what is available downtown is in older buildings without large blocks of space. Many feel it seems ready for new buildings.

7 World Trade Center: People looking to illustrate the strength of the market point to Seven World Trade Center, which World Trade Center site developer Larry Silverstein finished building in May. There were major concerns about the building's marketability, but it has filled about half of its 1.6 million square feet of office space. Weld takes this as a sign that the building is succeeding.

Open Questions

Despite the positive news literally surrounding Ground Zero, considerable concern remains about the signature pieces of the Ground Zero development.

Freedom Tower: The Freedom Tower, it seems, is immune to the sense of optimism about the prospects for commercial buildings downtown. It is commonly understood that Governor George Pataki sees it as his physical legacy to the 9/11 recovery, but many feel his political and personal commitment to the building has inspired him to push a project that may well fail.

The 1,776-foot tall Freedom Tower would contain about 2.6 million square feet of office space. It is further from public transportation than other buildings planned for Ground Zero, and is perceived as a possible terrorist target. There are no committed tenants for the building.

Governor Pataki says that government agencies will take at least one million square feet of space in the building, but critics do not see that as a guarantee. Two of the three gubernatorial candidates have expressed concern over the financial prospects of the tower. Eliot Spitzer has called it a "white elephant". While he says he is committed to building it if elected governor, he adds that he would reassess the project if the one million square feet were not leased when he took office.

The Other Towers: Some involved in rebuilding share Sptizer's concern. The Regional Plan Association has said the towers along the east side of the site -- bordering Church Street -- would be a better investment. It may make sense to build these buildings first, they say, gradually introducing new office space instead of glutting the market.

Designs for the three buildings are scheduled to be unveiled this week. At the moment, they are scheduled to be completed by 2012.

The Memorial: Civic groups who have been involved in the rebuilding would see the creation of a memorial as the primary immediate concern at the site.

"The lack of a memorial, the lack of a plaza, is a key problem," said David Kallick of the Fiscal Policy Association. "I don't think there's a problem with the buildings coming on line one by one as the market demand increases."

But the memorial has its own challenges. There is still controversy over how the victims' names will be displayed. That, combined with a general uncertainty over plans for the site, has made fundraising difficult. To date, the World Trade Center Memorial Foundation, which is in charge of building the memorial, has raised $132 million. Estimates for how much it will cost to complete the memorial range from $500 million to close to $1 billion.

Cultural Buildings: As Ground Zero is beset by funding concerns on all sides, it seems that the cultural buildings planned for the site have been orphaned.

"It's not on anybody's funding timetable," said Ric Bell of the American Institute of Architects. "Where does that leave culture on the site?"

The End of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation: Despite these open questions, the agency formed to direct rebuilding announced this summer that it would soon go out of business.

The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation arranged the design competitions for the master plan for the site and the memorial, played a role in the controversies over the Freedom Tower, and passed out billions of dollars in public money for post 9/11 recovery.

"The LMDC had a mission and we're nearing the end of that mission," its chairman, Kevin Rampe, said at the time.

Most of the power over rebuilding has always rested with the governor, and many agreed that the organization had outlasted its usefulness. With a layer of bureaucracy gone, the decision-making would be sharpened.

"Not that they were a negative force, but the cacophony of voices I don't think was the most expeditious way to get decisions made," said Wylde of the Partnership for New York City.

The agency does have some issues it must resolve before it closes its doors, however. There are still tens of millions of dollars in grant money to be distributed. The agency says it does not have exact numbers on how much money it has, but newspaper reports indicate that there is about $45 million in "community enhancement" grants and another $7 million in cultural grants remaining. It is not clear who will distribute this money if the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation doesn't.

The agency has also not developed design guidelines to go with the master plan for the site. These would determine what the site would actually look like, from the actual buildings down to light fixtures and curbs. Failure to put such guidelines in place has been a sticking point for those who say they are a necessary part of the master plan.

"These questions will be resolved over the next couple of months, Michael Haberman, a spokesperson for the agency, said of the issues surrounding the grant money and the guidelines.

But Bell of the American Institute of Architects says that the agency's biggest failure has been its inability to get such guidelines in place. While an opportunity has been lost by not having them ready before design work began on the buildings, he says they are still "desperately needed."

JUST A HOLE IN THE GROUND?

Two weeks before the fifth anniversary of 9/11, New Orleans marked the first anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. In many ways it was like the first anniversary of 9/11: the intense media attention, the public grieving, the sharp questions about recovery.

In response to criticism that rebuilding in his city was not moving quickly enough, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin made the comparison explicit.

"You guys in New York can't get a hole in the ground fixed, and it's five years later. So let's be fair," he said on 60 Minutes. Nagin was making a point that is regularly made in the editorial pages of New York's newspapers, by public officials, and even by those who are involved in the rebuilding itself. As a statement of fact, it is indisputable. But any public statements about Ground Zero are likely to evoke an emotional response. Nagin was criticized harshly, and soon said he regretted the remarks – on a trip he made to New York City last week to entice investors into contribute to the rebuilding of New Orleans.

"I will never again refer to that site as a hole," said Nagin. "It's a sacred site that's currently in an undeveloped state."

Â

Barging Back

Barges are poised for a comeback. Not that they ever left New York-the big flat vessels travel up and down New York waterways filled with petroleum, stone, rocks, sand, scrap and chemicals. Almost all of the home heating oil used on the East Coast comes through New York Harbor on barges.

And yet barges used to carry much more -- in fact, everything loaded on or off of ships from around the world. The great Erie Canal was built in 1817 for barges. But by the middle of the 20th century, bridges and tunnels and the Interstate highway system made transport of goods speedier and easier by trucks. Even garbage, once carried by scows (which are similar to barges), started being transported by trucks. Today barges carry just six percent of the nation's cargo.

With traffic-clogged highways and high fuel prices, far-sighted planners in New York are looking to barges once again.

According to a plan passed by the City Council in July, the city's trash will once again be hauled away by barge. Officials also hope that container ships will unload cargo onto barges as well.

Moving Containers

Until the mid-1970s, New York was a commercial harbor. "If you saw a pleasure boat, they were lost," says Eric Johansson, director of the Maritime Industry Museum in the Bronx. But then exactly half a century ago, a new kind of ship was created, container ships, which carry their cargo in truck-size containers that can be easily transferred to the back of a truck or attached to a locomotive. The container ships were huge and needed massive amounts of space to unload. This is what did in most of the commercial waterfront business in the city. In the city today, cargo unloads only in Brooklyn and Staten Island. Most of the container ships go to New Jersey ports. Now real estate developers have jumped into the old working waterfront to put up commercial and residential buildings.

Johansson, a former tugboat captain, bemoans the transformation. He wants to see more, not less, commercial traffic. And the way to do this, he thinks, is by bringing back barges. "Anything moved by water is more cost efficient than on the road. You gain a little speed with trucking, but when fuel costs go up, it won't be efficient. It's always cheaper to go by water. You don't have to build a road. You've got the waterway sitting there naturally."

Even a small, inland barge can carry 60 containers. That would make 60 tractor-trailer truckloads. "If you could take 60 18-wheelers off the road with one barge, why wouldn't you want to do that?" says Tom Wakeman of the Port Authority. Larger barges can carry 200 or more containers.

The idea of using barges for containers is not just a dream. For three years, there was a federally-funded pilot program to move containers from the giant ships in New York Harbor to Albany, via barges.

The experiment failed. Different experts give different reasons why – it wasn’t given enough time, there weren’t enough trips back and forth, there wasn’t enough marketing, not enough effort to sell the shippers on the idea, too many marinas blocking the barges along the waterway into Albany, etc. Tom Hannan, who is in charge of the barge program for the Port Authority, believes the barge program might simply have been ahead of its time. The shippers weren't ready to embrace it because they didn't see a cost or time savings. As fuel costs grow and the ports and highways become more congested with ever-greater imports, that will change, and the economical barges will show their virtues.

Today the Port Authority is planning another pilot program, this time to transport containers by barge to Bridgeport. Since Bridgeport is along the truck-congested I95 highway corridor, shippers might be more inclined to use the barge service. They are also looking at services to Camden and Providence.

Hannan of the Port Authority is optimistic. The Albany program "was an incredibly complicated process, but we learned a lot,” he says. “We're in a position to do much better.”

Moving Trash

In a few years, whether or not the container/barge program takes off, barges will be more numerous, because they are slated to start collecting and hauling off the 12,000 tons of trash city residents produce each year. Garbage trucks will load their trash onto barges at transfer stations along the rivers. The capacious but unglamorous vessels will then carry the unglamorous waste off to landfills in other states. That will ease traffic, odors and road wear, saving 3.5 million miles of driving a year.

Today, most of the garbage goes to transfer stations in poor neighborhoods in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens for compaction. Then it is trucked out to landfills. The new method is meant to be more equitable. One of the transfer stations will be on the Upper East Side in Manhattan.

Though barge proponents say that water transport is economical, the cost for transporting the city's trash will increase from $77 to $107 per ton. Officials say that in the long run, the costs will be lower, but implementation will be more costly than the current method.

It took years of wrangling, but the City Council passed Mayor Michael Bloomberg's trash plan in July with a vote of 44 to 5. It should be implemented by 2009, according to Bloomberg.

Soon, the big unassuming worker bees of the rivers are likely once again become a major force in moving items to and from New York.

Â

Democrats Move in on Staten Island's Republican South Shore

|

New York State Senate-District 24: • Bob Helbock • Andrew Lanza Other Races • New York State Assembly- District 21: Ethnic Politics in Changing Flushing • New York State Senate-District 13: Bringing the Money Back from Albany

|