Keeping the Middle Class

Communities across our nation are searching for ways to deal with the worst fiscal crisis we've seen in decades. And New York City is no exception. We're facing a $4 billion budget deficit. We've lost 50,000 jobs already, and it seems like every day we learn of more layoffs in the financial sector and beyond.

You may hear many competing theories on how to improve our economy, but one thing is clear: The surest way to guarantee that our economy gets worse is by allowing our basic quality of life to deteriorate.

If we let an economic downturn erode our commitment to things like education and safe streets, we'll see the middle class begin to flee our city, just as they did in the 1970s. And when they leave, they take their tax dollars with them. But it won't just be residents -– we'll see tourism decline as well, costing our city millions in revenue and countless related jobs.

Soon we'll find ourselves having to raise taxes on those who remain, making the city less affordable and doing little to dig ourselves out of our quality of life hole. And before long, it will become a vicious cycle that gets harder and harder to escape.

Securing Our Services

That's why it's so critical that while we look for ways to tighten city spending, we keep investing in strong schools, safe streets, efficient mass transit, clean parks and public spaces. Smart planning on the part of the City Council and the Bloomberg administration, like paying down billions of dollars in future debt, has prevented us from having to make more drastic cuts so far.

The council has already fought successfully to protect things like police classes and classroom funding. We are also going to need to do without some programs that may be good but have to give way to the services that are the most essential.

But if we're going to continue to fight for these shared priorities and core services, we'll need to find additional revenue somewhere. The first step is creating a balanced tax approach, coordinated with the state to avoid piling on any one group of taxpayers. To the greatest extent possible we need to avoid taxes that are too onerous on businesses and threaten to drive commerce outside of the city.

And we need to make sure we're not squeezing middle-class New Yorkers and that we keep money in the hands of those who are most likely to spend it on necessities, fueling economic activity. At the same time, we'll ask those who have benefited most from the opportunities New York City offers to give a little back while we weather this storm. That's why I've proposed reforms to the city's income tax structure to create three new tax brackets for New Yorkers making over $300,000 a year, while easing the burden on those making the least.

Additionally, we'll look to the federal stimulus funding that's been directed to states and municipalities for exactly this purpose to help us invest in our infrastructure, create jobs and avoid laying off police officers, firefighters and teachers.

We're currently working with the state to see exactly how much of that stimulus funding will be directed down to New York City. But we're hopeful that Albany will recognize the importance of giving New Yorkers their fair share. New York City is the main economic engine for New York State, and the state government has as much stake as anyone in seeing that we continue to thrive.

Wall Street to Main Street

Now just as we're at the center of economic activity for the state, we are also at the epicenter of the fiscal crisis for the entire nation. As the home of Wall Street, New York City has felt both the rise and fall of high finance in recent decades, and we have as much of an interest as anyone in seeing Wall Street recover.

The Obama administration is working to reform the financial industry. We have great faith that it will create a regulatory system that strikes the necessary balance –- restoring stability and investor confidence in the market, without creating an environment that stifles innovation.

Wall Street will rebound, and the global economy with it. Meanwhile, we in New York City need to focus on diversifying our economy outside of finance. For too long, we've been overly dependent on Wall Street to fill our coffers and fund our growth. Now we're being forced to look around at areas we may have neglected.

New York City is home to 220,000 small businesses that account for 50 percent of all private sector employment. We need to make it easier for those businesses to stay afloat and for new ones to open. That's why I recently announced "Open for Business," a series of proposals to support the small business community that came out of the council's conversations with real business owners.

For example, we'll make it easier for new businesses to start up by streamlining the application process for city permits and waiving permitting fees for a 12-month period. We'll also better coordinate agency inspections, to keep business owners from waiting months before they can open their doors.

We'll support businesses that already exist by keeping more local dollars in our local economy. We'll work to change state contracting law, to allow us to give preference to qualified local businesses, and launch a campaign to promote hubs of retail, dining and entertainment around the five boroughs.

And finally, we'll eliminate red tape and help keep government out of the way of business growth. We'll start to evaluate the effects of new rules and regulations on small businesses –- before they get passed –- and we'll create a temporary late fee amnesty for small businesses that are drowning in unpaid fines.

Drawing in Emerging Technologies

In addition to supporting our small businesses, we need to start investing in new and growing job sectors that can further contribute to the diversity of our economy. Many of these industries already exist in New York City, and with a little help, they have the potential to grow by leaps and bounds.

For example, we're already a home to cutting edge research for the biotech industry. But when it comes time to turn that new discovery into a new drug or a new medical device, biotech companies often leave our city for other places –- places with aggressive programs to court these companies.

Thanks to the Bloomberg administration, we've already started by creating more commercial laboratory space. And recently, I proposed a City Biotech Tax Credit that will help dozens of biotech companies equip their facilities and train their staff, encouraging them to locate, and stay, right here. By becoming more competitive, we'll create nearly a thousand new high-tech and high paid jobs.

We're not going to climb out of this recession overnight. But by targeting resources to key job sectors and maintaining our commitment to a high quality of life, we can begin to rebuild. We can ensure that New York remains an international city, one whose top-tier colleges and career opportunities attract the brightest talent from around the world. And we can help our city to emerge from this economic crisis stronger than ever before.

Christine C. Quinn has been speaker of the City Council since 2006. She represents Manhattan's 3rd district and is running for re-election.

Tax Justice in a New Economy

Falling revenue has torn gaping holes in our city and state budgets, but our mayor and governor are wearing blinkers. Narrowly focused on the spending side of their fiscal plans, they see cuts in jobs and public services as the solution to the fiscal crisis. They're not looking at the revenue possibilities that would help them avoid these cuts -- cuts that are unwise, unjust and unnecessary.

The proposed cuts are deep and devastating. They want to chop hospital and school funding, raise subway fares, deprive vulnerable students of drug and alcohol counselors, shut free school dental clinics, cut ambulance service, contract out programs for seniors and youth, and eliminate thousands of jobs and set the stage for devastating cutbacks in our libraries and cultural institutions.

District Council 37, the city's largest municipal employee union, is fighting to defend our health care, our schools and our jobs. But, in doing so, we have decided that one of the first things we have to do is fight to reframe the role of government in New Yorkers lives.

Economist Jeffrey Sachs recently wrote that Americans are now paying the price for the Reagan-era-inspired rejection of "government solutions" to the problems of health, poverty, education and the environment. This, he continues, "kept our taxes as a share of national income lower than Europe's by focusing on the private sector."

So, if the current global economic crisis has taught us anything it should be that if government had played a larger -- especially regulatory -- role in our lives, the private sector might not have been able to trample millions of Americans' hopes and dreams.

Private Work in the Public Sector

To help with that reframing, we've researched and analyzed city spending only to find that under this mayor, the city has handed over some $9 billion to an unelected, unaccountable "shadow government" of private contractors and outside consultants. A number of these are no-bid, unregulated contracts. Given what's happening in America today, it should come as no surprise that this process undermines the transparency and accountability the public deserves from government.

We examined some 10 contracts between private companies and eight city agencies and identified a $130 million savings. And that's after a look at only a fraction of the 18,000 deals the city has made with private entities that, in many cases, provide the very same service city employees are paid to provide.

Frankly, that makes no sense. Especially when you consider that with city employees who are tested, investigated, fingerprinted and vetted the city and taxpayers know who and what they're getting. As far too many scandals have shown, the same cannot be said for private contractors and their employees.

To the Streets for Taxes

In addition to this analytical approach, we're taking to the streets. Joining with other unions and our community-based allies we're reaching out and talking to our elected officials.

In New York City, on March 5, over 50,000 members of DC 37 and a broad coalition of unions joined community activists and took our fight to City Hall.

On March 17, scores of New York City Department of Education substance abuse counselors, who service some 1.1 million school children at 1,400 schools, went to Albany to tell lawmakers that the proposed state and city budget cuts would gut a critically important substance and alcohol prevention and intervention program, put city school children at risk and result in the layoff of some 300 experienced drug counselors. On March 31, thousands of AFSCME members from around the state will take their message to Albany again.

Everywhere we go, we're urging lawmakers to focus more on the revenue side of the budget by canceling the most devastating budget cuts we've seen proposed in decades, and instead support public services with fair taxation.

The mayor and the governor want everyone to share the sacrifice except the ones who can best afford to pay, the richest New Yorkers.

Frankly, I simply can't see depriving the vast number of uninsured people of health care or letting teenagers fall into drug dependence, when modest tax increases for those who can afford it could replace these cuts. I can't see slashing services and cutting the jobs of those who know best how to deliver them when all we have to do is ask for a reasonable contribution from the extremely wealthy New Yorkers who can well afford to shoulder their fair share of the burden. It's a no-brainer.

Time to Tax the Wealthy

After all that is what the 2008 presidential election was all about. After eight years of tax giveaways to the rich and negligent regulation of business, the American people demanded change. They voted to get rid of those who said "government is the problem, not the solution." They chose to acknowledge that government does things for us that we often can't do for ourselves. They voted against policies and a philosophy that threw our nation's and the world's economy into a tailspin and saw millions of families thrown out of their homes and millions of breadwinners thrown out of work.

Have our city and state leaders learned nothing? Their spending cuts would slow economic activity at a time when we need a speedup. Their budgetary attacks on the working class, the middle class and the poor are the exact opposite of what President Obama is trying to do. He is going all out to save jobs while they are wiping out jobs. I agree with the president that we must invest in one another and build up services like hospitals and schools that only government can provide.

I ask the mayor and governor to take a serious look at the modest tax increases I am talking about. The Fair Share Tax Bill proposed by progressive legislators in Albany would raise rates by less than 1.5 percent on those with incomes over $250,000. It would cost someone making $300,000 a year — who brings home almost $6,000 a week — just $88 a week more. It would bring in $6 billion to the state.

The fair tax plan would simply ask the people who have gotten all the tax breaks under both the Bush and Pataki administrations to pay their share to reduce the misery the broken "bubble" economy has dumped on the rest of us.

I am also reminding the mayor that the city is still squandering billions a year on contracting out public work to the private sector. We have shown the city how to save money by reducing some of this waste. No responsible government can in good conscience cut vital services and lay off hard working public employees while real savings are within reach.

Using Tax Incentives Wisely

Whether the economy is booming or in a bust, it’s best to know where your taxpayer dollars are going. But good luck if you want know how those tax breaks are allocated to businesses in New York City -- all in the name of job creation. As our city navigates the current financial crisis and prepares to distribute between $4 billion and $5 billion of federal stimulus monies, we can’t pretend it is business as usual.

Most New Yorkers are surprised to learn that it’s nearly impossible to know how much money is allocated to companies for job creation or even how many jobs are created in exchange for tax breaks. Different agencies have different criteria and reporting requirements. For example, the largest economic development tax incentive, recently reauthorized as the Industrial Commercial Abatement Program, gave $500 million in property tax breaks last year, but it has no job reporting requirements.

At Good Jobs New York we pay close attention to the Web New York City Economic Development Corporation and its Industrial Development Agency, which last year allocated more than $48 million to mostly large fortune 500 firms whose threats to leave New York City are highly questionable. Using tax breaks as corporate giveaways will not revitalize our economy nor prepare it for the future.

Moving forward, and using the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act as a launching pad, city officials need to tighten up how we award tax incentives to large corporations. By doing so, we can use efficiency and transparency to help create good jobs for all New Yorkers and a healthy business environment for all companies.

Transparency is Key

First, the city must make public the costs and benefits and outcomes of its job retention subsidies funded by the federal stimulus package as well as upgrade the online reporting for the city's incentive packages. Today there is no central database for keeping track of this information, but people are eager to know what is happening.

According to the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, the federal recovery website received 150 million hits in its first two and a half weeks -- even though there is little data there. New York City has proposed a “stimulus tracker,” but it’s unclear if it will include data on jobs, wages and subcontractors or include data on the city's incentive packages.

This type of needed transparency -- uncovering the job creation, or lack thereof, of certain incentive packages -- is not unprecedented elsewhere.

Thanks to improved reporting at the New York City Industrial Development Agency, we’ve learned that some firms have received subsidies in the past even though they reduced their New York City workforce. Some never had to promise to create jobs in the first place. Pfizer, for instance, received a subsidy package, which could have been worth up to $47 million, from the city in 2003 but shut its Brooklyn plant in 2008. The city also failed to attach job creation guarantees on more than $1 billion in subsidies awarded to the Yankees and Mets for their new stadiums.

The city and state used similar tactics -- and had similar results -- with funding they received after September 11, 2001. Then, about $2.7 billion in Community Development Block Grants and $8 billion in tax-free Liberty Bonds were aimed at getting firms to stay or return to Lower Manhattan. But little of it benefitted the small businesses hardest hit, like those in Chinatown and the Lower East Side. After receiving these grants, large firms including American Express and HIP admitted they would have returned to Lower Manhattan without them.

The same year, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's own company, Bloomberg, L.P., turned down a subsidy for its headquarters in Midtown. The mayor said that businesses like his don’t make location decisions based on taxes, because they are such a marginal cost. Ironically, in recent weeks the mayor has waffled, saying just the opposite.

Prior to September 11th, community block grants and federally tax-exempt bonds were intended to benefit low- and moderate-income people and to create affordable housing but these requirements were waived by the Bush administration. The Bloomberg administration is hoping these rules will be waived again by leaders in Washington for the stimulus funds, creating an invitation for a replay of the 2001 corporate giveaways.

Eliminate the Silos

The city can spend less and get more by eliminating the silos that exist between its economic development and workforce development policies.

Tax breaks should be used as a leverage to place New Yorkers who need jobs at firms that get the tax breaks. For example, the New York City Economic Development Corp. and Industrial Development Agency have allocated hundreds of millions of dollars to companies, yet neither of them collaborate with training agencies like the city’s Workforce One Centers or private job training or readiness programs serving unemployed or under-employed New Yorkers.

When a firm accepts taxpayer subsidies, there should be an effort to connect them to potentially qualified New Yorkers who need jobs. There are plenty of New Yorkers who need jobs, and it’s about time we strengthen ties between companies that are hiring and our employment and training agencies.

Invest Wisely

The city should not only make sure jobs are created, but that good jobs -- those with an emphasis on helping those most in need -- are being created. Why give subsidies for jobs that keep people in poverty? Firms should pay employees a living wage and provide health benefits. Otherwise, taxpayers are paying twice: subsidizing the company and paying for social safety net programs.

It’s bad for the morale of responsible businesses to see low-wage companies receive tax breaks. Making sure New Yorkers have money in their pockets is a sure way to generate the economic activity we need.

Incorporating job quality standards won’t cause companies to flee New York City. In fact, we’re surrounded by places, including New Jersey and Pennsylvania, which have wage and health care standards attached to their subsidy programs.

Think Regionally

Most likely the biggest threat to the creation of a rational economic development policy is the economic war among the states. The Obama administration should encourage regions to work together by discouraging the use of tax incentives that “poach” companies from one location to another. New York, New Jersey and to a lesser extent Connecticut and Pennsylvania are in a race to the bottom by reducing taxes for some companies who promise to relocate.

But as mentioned earlier, taxes aren’t the main reason a company moves or expands. Access to the necessary workforce, infrastructure, suppliers, customers, affordable housing and school quality are critical in the decision-making process. Investing in these will give taxpayers the best bang for their buck

If a company doesn’t have the business basics, giving it tax breaks is futile. The economic war among the states benefits secretive site location consultants who pit cities and states against each other. To make the region stronger, officials should work together to magnify individual and collective strengths, not belittle them.

Bettina Damiani is the project director for Good Jobs New York.

How to Plug the Growing Budget Gap

Less than four months before Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council must sign off on next year's budget, billion-dollar questions multiply. New reports from the Independent Budget Office and City Comptroller William Thompson suggest the city's budget gap in fiscal year 2010, which begins July 1, 2009, is much bigger than the January preliminary budget indicated and that the mayor's gap-filling plan has its own billion-dollar holes.

At the same time, Council Speaker Christine Quinn, has proposed a big alternative to the mayor's fiscal plan. With his focus on across-the-board service cuts and a large increase in the sales tax, the mayor has placed the biggest new burdens on lower- and middle-income New Yorkers. The speaker would shift at least a billion dollars of that sacrifice to higher-income New Yorkers by restoring the personal income tax structure to more progressive levels.

Billion Dollar Questions

Testifying before the City Council on March 9, www.ibo.nyc.ny.us Independent Budget Office director Ronnie Lowenstein estimated that the 2010 gap is now $1.2 billion greater than estimated in the mayor's January plan. Most of that new gap comes from the IBO's projection that tax revenues will decline by $1.3 billion more next year than the mayor projected. Assuming that's true, that means, of course, that the mayor and council would need to come up with yet another billion-dollar plus package of new revenues and/or service cuts.

The primary reason for the increased gap, according to Lowenstein, is the rapid increase in job losses in the city, particularly in the financial world. The IBO projects the loss of 270,000 jobs from peak employment in the first quarter of calendar 2008 through the second quarter of calendar 2010. That's 30,000 more jobs lost than the office estimated in January. The city has already lost 59,900 jobs since January 2008 -- but, according to the budget office, the worst is yet to come.

In particular, the securities industry - the highest paying sector within the financial industry - is projected to lose 48,800 jobs by mid-2010, a decline of over 25 percent from its peak in 2008. Wall Street firms which, as recently as 2006, had profits of $21 billion, had net losses of $11.3 billion in 2007, and the IBO projects net losses of $45.1 billion in 2008.

City Comptroller William Thompson Jr.'s March report, Comments on the Preliminary Budget for FY 2010 and the Financial Plan for FYs 2009-2013, accepts most of the mayor's 2010 tax revenue estimates, but worries about nearly $1.9 billion of shaky assumptions in the mayor's plan for closing the 2010 gap. He identifies two potential problems: increasing revenues from the city sales tax by nearly a billion dollars, which requires state approval, and the $757 million in labor concessions, which would require the approval of municipal employee unions.

The city comptroller sees much bigger problems for the 2011 to 2013 period than the mayor. He sees risks in the administration's financial plan of about $3 billion in each of those three years, so his projections of future deficits are much higher than the mayor's. Gaps could be as high as $6.9 billion in 2011, $7.0 billion in 2012 and $6.9 billion in 2013. These projections dramatize the difficulty the mayor and council continue to have catching up with escalating gaps.

The End of the Rollover

Adding to the problem is the disappearance of the surpluses the administration has come to rely upon. At the end of each of the previous four years, the city had surpluses averaging over $4.1 billion and used those surpluses to pre-pay an equal amount of the next year's expenditures. That meant, of course, that in those years the city did not have to find an average of $4.1 billion in new taxes or expenditure cuts.

The current fiscal year, 2009, benefits from last year's $4.6 billion surplus, which helped offset the escalating problems this year. In fact, the IBO estimates this fiscal year will see a $1.6 billion surplus, which will be part of the gap-filling program for 2010. But the comptroller points out that, surplus pre-payments aside, actual operating expenses in 2009 will exceed current-year revenues by $3.8 billion.

Well aware of the forthcoming surplus depletion -- if not of the more severe economic and fiscal downturn in recent months -- the mayor has been cutting agency spending more or less across-the-board since the January 2008 preliminary budget and financial plan, as explained in the February 2009 finance column. One worrisome example of the impact of these cuts (made in January 2008, November 2008 and again in January 2009) is, as the city comptroller notes, the aggregate cut of $944 million in city education funding in 2010.

The comptroller notes that the federal economic stimulus plan could provide the city with about $1 billion in education funding in each of the next two years. That money would "alleviate many of the proposed reductions in state funding, allowing the city to avert the proposed layoffs," but would provide "no additional gap closing relief."

Billion Dollar Answers

Only two of the mayor's four roughly billion-dollar answers to budget deficit in his January plan look solid in mid-March: the on-going agency cuts, saving another $1 billion in 2010, and the anticipated $1 billion Medicaid relief money in the new federal economic stimulus plan. The other two noted by the city comptroller - nearly a billion dollars from increases in the sales tax -- and three quarters of a billion dollars in labor concessions on employees health and pension benefits - are highly uncertain.

So that leaves room for at least $2 billion in alternative revenue/expenditure packages - over $3 billion if the worst-case IBO scenario is acknowledged. It's in this context that the council speaker, Christine Quinn introduced on Feb. 12 a major tax revenue proposal that would, as she says, "balance the city's income tax structure and avoid sales tax increases." (For Quinn's explanation of her proposal go here.)

There are two essential parts to the Quinn plan: The first would eliminate the city personal income tax for all those - currently 224,000 families - who pay no state or federal income taxes but do pay the city personal income tax. The savings for those families (earning up to $46,000) would average $321 per family.

Quinn would pay for the revenues lost in reducing lower-income tax burdens (about $72 million) and abandoning the mayor's sales tax increase by creating three new tax brackets for those taxpayers with annual taxable income over $297,000. The current top rate - 3.65 percent - would increase to 4.25 percent for those filing jointly and making $297,000 to $532,000; to 4.45 percent for those making $532,000 to $1.2 million; and to 4.65 percent for those with incomes over $1.2 million.

A few days after introducing her tax proposal, Speaker Quinn, along with State Sen. Liz Krueger and the Drum Major Institute announced a proposal for state legislation that would eliminate the income tax on low-income people. The partners emphasized the economic benefits of putting $321 in the hands of lower-income New Yorkers.

That, of course, is only a first step. The state also would have to pass legislation to implement the higher tax rates on more affluent New Yorkers proposed by Quinn. Bloomberg has been reluctant to take that step, even though he introduced -- and the council immediately passed -- a similar, but temporary, proposal during the fiscal crisis in November 2002.

The larger Quinn plan is hardly radical. In fact, the city's top income tax rate was 4.45 percent from 1991 through 1998, under Mayors David Dinkins and Rudolph Giuliani and then, under Bloomberg, from 2003 through 2005. What's most surprising here, then, historically, is that such higher rates have not been re-introduced in earlier gap-filling plans.

There is no lack of other big, and more progressive, revenue alternatives to the mayor's sales tax proposal. For instance, the IBO's February www.ibo.nyc.ny.us Budget Options includes two that the mayor himself has proposed at one time or another, but no longer advocates: restoring the city's commuter tax to bring in $715 million in 2010 and instituting a more progressive commuter tax would bring in $1.4 billion.

Lessons from Reports

In the midst of this fiscal crisis and initial mayoral/council skirmishing, two reports mandated by the City Charter were released in February, the Preliminary Mayor's Management Report for Fiscal Year 2009 and the Annual Report on Tax Expenditures, Fiscal Year 2009. Although little known, they include some useful lessons as tax plans are debated.

Take the preliminary management report, which the mayor tried to eliminate a few years ago through his Charter Revision Commission. It is supposed to provide early data for the current fiscal year, data that might prompt budget changes for the following fiscal year.

Slim as the up-to-date data are in education, one indicator stands out. Class sizes in the elementary and middle schools, after some small decreases between fiscal 2006 and 2008, have gone up in this school year in all grades except fourth. In grade three, class size now averages 21.9, up from 21.0 just a year ago. In fact, class size in all grades kindergarten through the third are now higher than they were in 2006, one early result of those nearly $1 billion of cuts in 2010.

Then there is the report on tax expenditures, which records the impacts of selective tax cuts that have been established over many years. Some of these are questionable million-dollar and billion-dollar programs that can starve revenue needs at times like these. One of the biggest, the Industrial & Commercial Incentive Program, whose economic development assumptions have long been challenged by Good Jobs New York, costs the city $500 million in lost revenues in 2009. (For a related commentary, go here.)

City insurance companies, unlike all other companies, pay no city business income tax, at a cost to the city (in 2005) of $256 million. Co-op and condo owners gain from an allegedly temporary property tax abatement, introduced in 1996, but which continues today, at an annual cost of $337 million. Battery Park City, whose residential and commercial property is exempt from city property taxes, costs the city over $150 million annually. Then there is Madison Square Garden, which since 1984 has paid no property tax, costing the city $12.2 million in 2009.

Baseball, however, trumps basketball and hockey for outrageous public subsidies. The Independent Budget Office pointed out in January that the city's exemptions and subsidies for the new Yankee Stadium will cost the city $362 million over 40 years. Including federal and state exemptions and subsidies as well, the total public cost will be $855 million. In fact, as the mayor proposes a billion dollar increase in the sales tax for New Yorkers, the Yankees are enjoying a city sales tax exemption he granted them on construction materials, which costs the city over $20 million.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.

In Albany, Budget Battles Behind Closed Doors

Gotham Gazette image by Ya-Hsuan Huang

State Republicans said it would happen under the cover of night with little to no warning. Good government advocates said legislators would be ordered to their chambers and reminded there is no time to waste. Printers would roar to life, packets of hot paper would be distributed and in a blink of an eye, groggy legislators would vote to approve New York State's 2009-2010 budget.

To a great extent, the cynics were correct. The legislature and the governor did agree on a budget deal behind closed doors -- over the weekend and late at night. The documents were printed over the weekend. It now appears, though, that members of the Assembly and Senate who are so inclined will have a few days to read the nine bills, some with thousands of pages, before the expected vote early this week. Nevertheless observers reviewing recent events still say the budget process this year has been one of the most secretive negotiations in recent memory. (Gotham Gazette will continue to cover the budget throughout the week in Eye on Albany and The Wonkster.)

New York State faces a $16 billion budget gap and by law must pass a balanced budget by Wednesday. As the clock ticked down last week, about all one heard in the Capitol were rumors. At a recent negotiating session with the three men in a room (otherwise known as the governor, Assembly speaker and Senate majority leader) a reporter asked Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver for one detail about what is actually in the budget. Silver replied, "We'll have an on-time budget."

At first, it seemed things might be different this year. Gov. David Paterson started talking about the state's perilous finances months ago, warning that the state would have to make "draconian" cuts. Paterson even released his budget proposal in December -- earlier than most governors have done -- and used his State of the State address to hammer home the need for fiscal responsibility and shared sacrifice.

All three Democratic leaders have, at one point or another, pledged to reform Albany and ensure state government would be more transparent. The Senate Democrats started a Web page and a hot line to take budget suggestions from the public.

Now, though according to Blair Horner of the New York Public Interest Research Group, the leaders seem to have gambled that an "on-time budget" means more to voters than "transparency." Instead of openness, the three Democratic leaders hammered out the budget in closed-door sessions with limited, if any, input from Republican leaders.

"Talk is cheap," said Horner. "Reality is hard."

Crafting a Budget

New York State's budget process in kicked off when the governor introduces a budget proposal in January. The legislature's financial committees then hold hearings to review the soundness of the governor's plan.

According to the New York State Department of Budget Web site, "the legislature, primarily through its fiscal committees -- Senate Finance and Assembly Ways and Means -- analyzes the governor's spending proposals and revenue estimates, holds public hearings on major programs, and seeks further information from the Division of the Budget and other state agencies."

In most years, both houses of the legislature would pass separate budget bills, and then, since 2007, they would hold conference committees to discuss differences between their separate budget bills -- an attempt to clarify the process. "Under budget reform legislation passed in 2007, the legislature is required to use a conference committee process between the two houses to organize its deliberations, set priorities and reach agreement on a budget," the Division of Budget Web site says.

The legislature held hearings on Paterson's proposed budget earlier this year, but so far the leaders have chosen not to hold another round of conference committees.

The Quiet Before the Storm

No one doubts the state faces a dire budget situation. Up until the last minute, though, it was hard to detect that from the scene in the Capitol. Last week, normally talkative Democrats scuttled away from reporters who had questions about the budget on their lips. Near the Senate chamber Sen. Eric Schneiderman blurted to a reporter, "What do you want from me?" The reporter shot back, "I want answers!"

In all fairness, Schneiderman might not have had the answers since the three men in the room stingily parceled out information. As the negotiations dragged on, legislators who were told about parts of the deal dished out tidbits on what they thought might be in place but warned that things were steadily shifting.

Legislative action in the Senate slowed to a crawl in recent weeks as the focus shifted to the budget deal. The Senate spent the last few weeks honoring citizens and commending the recently deceased rather than passing substantive bills. Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith, when asked about serious pieces of legislation, repeatedly said they will be addressed "after the budget."

The Assembly, thanks to a Democratic supermajority, moved quickly on again approving bills that it had passed in previous years, bills addressing issues like Rockefeller Drug Law reform and rent control. However, the members hesitated to consider new legislation knowing that their action would be futile without support from the Senate. Silver did not act to pass his compromise plan to address the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's financial straits, nor did his house vote on an income tax increase for the wealthy, a measure that is now in the budget bill.

Hopes for Transparency

Advocates of open government initially thought they had allies in the Democratic leadership. Paterson, for example, had made a number of comments about his commitment to ending the secretive budget practices, which long plagued Albany.

Advocates had solidified relationships with the new majority after years when Senate Democrats -- then in the minority -- struggled to gain a seat at the table and to have their input taken seriously. At the same time, good government groups pushed to make the budget process more open.

Much, though, has changed since then -- as evidenced in the Democrat's new attitude toward the budget conference committees.

The 2007 law that created the committees was passed when the Republicans controlled the Senate and Democrats controlled the Assembly.

And Silver signed on. In a 2007 press release now being distributed by Republicans, the speaker said that conference committees would "move our state's budget process in the 21st century with a strong constitutional emphasis on mutual respect between the executive and legislative branches in forging a fiscal plan for our state. We will continue to rely upon the joint conference committees. We will have a more transparent, more easily understood budget process."

This year, with Democrats controlling both houses, Silver said there is no need for conference committees. "We're all Democrats," he said. "We're not going to have big philosophical differences."

Republican Minority leader Dean Skelos has said that not holding conference committees is illegal. But Silver has repeatedly declared that, if there are no differences between the budget bills in the two houses, there is nothing to be discussed in conference committees. In fact, Silver has said, there might not even be separate Assembly and Senate budget bills. For his part, Smith repeatedly insisted that he would hold conference committees. But as of Sunday night, with the budget apparently all but certain, that had not happened.

Those who observed conference committees in previous years point out that they were heavily scripted and did not actually produce more open government. Legislators would use the meetings to give speeches and hold their substantive discussions in private. By doing away with the committees and one-house budget bills, however, Silver is admitting that they were only window dressing on an ugly budget process -- just another way to placate the public.

Barbara Bartoletti of the League of Women Voters noted that the legislature fought to amend the budget process under Gov. George Pataki because he kept the budget process notoriously secretive. "It was known as Fort Pataki," she said.

According to Bartoletti, Gov. Eliot Spitzer made it a priority to open up the process and now Paterson, Smith and Silver are disregarding that work.

"This is a blatant violation of the law they passed in 2007!" said Bartoletti. "If regular people violate the law they get in trouble, but apparently these guys think they are above the law."

At a briefing Friday, reporters asked Paterson about the lack of transparency in the budget process. "I think there should be transparency in terms of the process and openness in terms of government," Paterson responded. "However, when you are in a budget position, it is very hard to negotiate in public. You never see President Obama and Senator Reid and Speaker Pelosi do it. You don't see it in any other state." And Paterson continued, "You don't see it in labor negotiations and I dare say that your negotiations with your own media outlet, your contract, is not, the last I checked, publicly observed."

Paterson failed to mention that his salary is paid by the taxpayers and reporters' salaries are not.

"There comes a point in the negotiations," continued Paterson, "where anyone who is really negotiating has to take things off the table. This is a very difficult endeavor, and it's hard to do it when the advocates you are fighting for are right there."

New Leaders, Old Habits

Silver, of course, is the only leader remaining from 2007. This year's budget negotiations took place with two new leaders -- Paterson and Smith, both of whom are considered weak and vulnerable. Smith has been rendered powerless by the combination of a slim majority and indecisive behavior. Paterson, thanks to plummeting poll numbers and his own brand of indecision is seen by many as nearly "irrelevant."

Smith and Paterson apparently hope that an on-time budget, no matter what it contains -- or how it's drafted -- will make them look responsible to the public and give them a political boost.

In addition, the lack of transparency might have helped Smith move things into the budget that would be controversial to some members. His majority is so slim that he can't afford "no" votes from any Democrats. That is why instead of passing legislation on drug law reform Smith has included it as part of the budget negotiations.

"The thinking on this issue is that there is an explicit rush to get this through," said Robert Gangi, the executive director of the Correctional Association of New York State. They wanted to have it included as part of the budget so that neither side can cherry pick. They have to vote up or down for the whole kit and caboodle."

The three announced they had reached a deal on drug reforms on Friday but did not offer a detailed account of what was agreed on.

Health care advocates have spent the last week using advertisements to target individual legislators and alert citizens about what they think will be tremendous cuts to health care funding and Medicaid payments to hospitals.

William Van Slyke from the Healthcare Association of New York, which represents health care networks and hospitals, thinks it is important to make sure legislators and voters know exactly what kinds of cuts are being considered. But he said last week, "Rank and file legislators don't even know what is in the budget. The Senate is in disarray."

For a week, information about "tentative" deals made its way around the Capitol before quickly being denounced or refuted by one of the three men in the room. Silver flatly denied a New York Times report that a deal on drug law reform had been reached, only to hold a meeting to announce the deal the next morning.

There was talk that a deal had been reached to institute the Bigger Better Bottle Bill, which would have put a deposit fee on noncarbonated beverages like water and tea and made beverage companies give the state unclaimed deposits. But it was reported quickly thereafter that the tentative deal had fallen apart. The bill is now back in as part of the budget deal, but only with deposits on water -- not juice or tea.

Bartoletti said there are many advantages for the three men in a room to keep the deal hush-hush as long as they possibly can. "Special interests still run Albany. It was probably lobbying or campaign contributions that killed the bottle deal but we won't know for two months till we see the contributions," she said before word came that parts of the bottle bill were back in. "It is the same thing with healthcare: We don't know because it is behind closed doors and special interests have their influence."

According to Horner, the budget crunch provides another convenient excuse to do business in secret. "This is unlike any other year," he said. "Thanks to the federal stimulus, the budget the governor presented is being entirely reworked, and it is being reworked behind closed doors."

"They are going to get away with it this year," said Bartoletti. "They think the public has a short memory and they will say they did it because of the financial crisis. They will even come out and say this was a bad process this year but we had to do it and we will do it better next year."

Opaque Government

Bartoletti describes this year's budget process as a "drive-by negotiation," because legislators driving away from leaders' meetings at the governor's mansion sometimes had the decency to pause briefly to give reporters placating, dismissive answers about what was discussed -- or, in the case of Republican leaders, to complain about how little input they actually have.

Last Tuesday, March 24, Republican legislators and open government groups stood together in the same room to call for Democrats to make the process more open. Skelos said he had not been invited to attend the "secret leaders meeting" that was going on just one floor below among the three Democratic leaders.

He said he thought Democrats would probably rush the budget through by issuing a so-called "message of necessity" that would eliminate the three-day waiting period normally required before the legislature votes on a bill. This would ensure, of course, that even fewer senators and Assembly members would have any idea about what's in the spending plan.

"Under the guise of getting a budget done on time, Governor Paterson, Senator Smith and Speaker Silver are prepared to rush through a budget in the dead of night with no time for public input or examination," said Skelos in a written statement.

Bartoletti expected that "legislators won't see the budget until 15 minutes before they vote and no one will even know what's in it." It was not quite that dire: Legislators will have part of the weekend and two days to review the bills. And, of course, getting bills on short notice is nothing unusual in Albany. Longtime Democratic Sen. Neil Breslin said he has "gotten bills two minutes before" he voted on them.

Last Tuesday, Smith canceled a number of public appearances to attend "budget negotiations." Meanwhile, the three leaders released a statement saying the budget deficit had increased by $2 billion to $16 billion. Republicans said the announcement was just cover for an impending announcement of a tax increase. Then news broke that Paterson had ordered the layoff of 8,900 state workers. The big three were nowhere to be seen.

At 3 p.m., school children in white shirts observed a poorly attended session of the Senate. The Senate asked the children to stand to be recognized, and then the few legislators in attendance voted to honor a recently deceased labor leader and tabled legislation pertaining to warning lights on bicycles. When the end of the session was called, a young girl looked up incredulously and said, "We came all the way for this? That's it?"

Taxing the Rich: An Idea Whose Time Has Come?

Photo from the Library of Congress

Henry Clews, a wealthy Wall Street financier and economic consultant, in 1910

Since the economic collapse in the fall, Americans have acquired a taste for watching CEOs squirm. They lapped up the scenes of executive sweating before Congress while being grilled about multimillion dollar bonuses and cheered in knowing their outrage had forced the heads of the major American car companies to abandon their private jets and drive to D.C. for congressional hearings. There's even a Brooklyn artist, Geoffrey Raymond who takes his portraits of CEOs to Wall Street to let passersby scrawl nasty messages on them.

So, not surprisingly, polls suggests that raising the income tax on the wealthy, popularly known as a Millionaires Tax, has strong support. Quinnipiac polls have found a steady 80 percent of New Yorkers in favor of such a tax hike. Labor and education groups are pushing hard for it using television campaigns and grassroots initiatives. With such strong popular support, a Millionaires Tax seems imminent.

Some legislators seem to have gotten the message. The Assembly is expected to vote to increase the tax on affluent New Yorkers. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver has stated that he won't "allow the burden of addressing the economic crisis to fall disproportionately on the backs of our already overburdened working families."

Yet, the plan has not attracted the support of a majority of senators, and despite some indications he might compromise, Gov. David Paterson still officially opposes the tax hike, preferring a mixture of budget cuts, some new taxes and increases in other taxes, such as the sales tax.

Higher and Highest

Although a number of different proposals for a millionaire tax have been discussed the most popular is the Fair Share Tax Bill that has been supported by advocates such as the Working Families Party and put forward in the Senate by Sen. Eric Schneiderman on Feb. 9. The Fair Share Tax Bill would increase the current 6.85 percent income tax rate to 8.25 percent for individuals who make more than $250,000 a year. Those making more than $500,000 a year would see their income tax rise to 8.97 percent, and those making more than a million a year would be taxed 10.3 percent. Currently everyone making over $40,000 a year -- from a schoolteacher to Michael Bloomberg -- pays the same 6.85 percent income tax rate.

Schneiderman's proposal was co-sponsored by 18 other senators. However, Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith opposes raising the tax rate for the wealthy. Smith, who previously called the measure a "last resort," said he believes such a tax would drive more affluent residents out of the state.

"During difficult economic times the senator is not in favor of raising taxes as a revenue generator," Smith's spokesperson, Austin Shafran, said. He added, however, that since there is support for the measure in the Democratic caucus, Smith will not stifle debate of the issue. "This fair share tax proposal will be openly and honestly debated on the floor of the Senate," he said.

Paterson has echoed Smith's sentiments, agreeing that a tax increase on the rich would be a "last resort." But with flagging poll numbers and public opinion heavily in favor of such a tax, spectators wonder if Paterson is wavering on the issue. At a banquet hosted by the State Association of Black and Puerto Rican Legislators last week Paterson said, "To those of you who are not here, who think you are too wealthy or too influential or have too great of a title to be part of New York's budget-balancing formula, let me make you aware that every New Yorker will share in the sacrifice to get this budget balanced." Paterson spokesperson Errol Cockfield reportedly told reporters afterward that Paterson's statement did not reflect a change in position.

Taxing, Not Cutting

Critics of the tax such as E.J. McMahon, director of the Empire Center for New York State Policy, said that unions representing public employees advocate the millionaires tax because they reject what he views as reasonable cuts to address the budget crisis, such as postponing increases in wages or benefits.

"The top one percent paid 40 percent of the taxes in the state in 2007," said McMahon. "People with a pie slice view of the economy think, 'Hey, if we jack up the rate 50 percent the rich won't notice it.' They think, 'Oh they have money! Let's get it.'"

According to McMahon, the state has relied on taxing the wealthy for too long. He noted that the reason there is such a budget gap this year is because the state got a large percent of its revenues from Wall Street and those revenues have plummeted. An increased tax on the rich, who have already lost great amounts of their wealth due to the market crash and who have "volatile" incomes is not a smart way to patch the budget deficit, he said.

Karen Scharff, executive director of Citizen Action, a group that strongly advocated Fair Share Tax Reform, disagreed. "It comes down to whether we should ask wealthy New Yorkers to pay a small amount in additional taxes to protect average New Yorkers facing job losses, foreclosures and school cuts," she said.

Scharff said that if one percent of New Yorkers paid 40 percent of the taxes that's because "they have 40 percent of the income in the state." As she sees it, tax rates on the rich have steadily been reduced for years and a small increase now is "only fair."

Schneiderman said his bill is not simply the product of unions but is supported by a "state wide coalition." He acknowledged that there will have to be cuts in the state budget but called his tax proposal "fair and a good way to raise money." It is time, he said, to stop "redistributing wealth from the working family to the rich," and with President Barack Obama having campaigned on the idea of a progressive tax, Schneiderman said he thought the mood is right to return a progressive tax to New York.

In the end, Scharff said, she expects to see Schneiderman's proposal taken into consideration during budget negotiations between the Senate, the Assembly and the governor. She thinks Smith and Paterson will bow to public pressure on the proposal and will change their stance.

In Schneiderman's view, New York's politicians have a history of "crying wolf" and suggesting cuts before ultimately restoring the spending because of public outcry. He said Paterson has been trying to hammer home the gravity of the situation by stressing the need for major budget reductions, but in the end Schneiderman thinks a tax increase on the wealthy will be part of the solution to New York's $14 billion dollar budget deficit.

The Opposition in the Senate

Given the Democrat's thin majority in the Senate, Smith's position may hinge somewhat on his members. Senators Jeff Klein and Pedro Espada Jr., who represent middle class and working class districts in the Bronx, have stood, along with Smith, in the way of the millionaire's tax as well as rent control laws that would benefit their constituents. "What Smith, Klein and Espada won't acknowledge is the tiny percentage of households in the city that earn $1 million a year, or even $250,000, after taxes," Juan Gonzalez wrote. "State records show a mere 393 households in Smith's Queens senatorial district reported incomes above $250,000 in 2005. More than 93,000, or 99.6 percent, were below that figure."

Scharff said that organizations like hers that helped the Democrats win their majority in the Senate will pay attention to where these senators' allegiances lie. She thinks most voters will pay attention as well. "I find it very puzzling that New Yorkers overwhelmingly voted for Obama and his progressive agenda, they sent a message to politicians and voted for change and yet somehow in New York it feels like we are going backward," she said. "New Yorkers won't allow it."

Creative Ways to Tax and Cut

Gotham Gazette image by Ya-Hsuan Huang

The Independent Budget Office's new Budget Options for New York City is a timely reminder of the many ways a city can balance its budget. As a slumping economy and declining city tax revenues threaten a fiscal crisis in New York, the IBO's eighth edition of its publication is a rich resource for a public debate about how to raise revenues, make spending more productive and set priorities for spending and cutting. Its analyses are comprehensive, impartial and non-ideological.

Budget Options also offers a useful contrast to the more crabbed style of budget presentation in Mayor Michael Bloomberg's recent financial plans. For the past year in particular, the mayor's Office of Management and Budget has provided few budget options, and many of those have been ephemeral. The OMB options, in fact, often look like mere placeholders -- general options with big numbers that are likely to change or be abandoned altogether.

For instance, the mayor's Financial Plan for Fiscal Years 2009-2013 offers only four broad components to fill next year's $4.4 billion deficit, three of which are likely to change dramatically. Yes, some $900 million in savings will come from agency cuts already well under way. But $900 million in sales tax increases, a projected $1 billion savings from labor concessions, additional state aid and a projected $1 billion from federal Medicaid relief represent, at best, fluid estimates.

In contrast, the IBO's Budget Options analyzes 70 ways the city could save money or raise revenues. The range is from the small -- eliminating grass clippings from trash collecting would save $2.1 million a year -- to the very large and controversial -- tolling the East River and Harlem River bridges, an idea once championed by Bloomberg that would raise $830 million a year.

The political range of the IBO's options goes from conservative, such as increasing the work week for city employees by five hours save $129 million, to liberal, such as making the city's personal income tax more progressive, which could raise as much as $455 million. In all cases, the IBO offers arguments both for and against each option.

Another Way to Cut

Because Bloomberg has been making across-the-board agency cuts regularly since fall 2007, usually in mid-year budget modifications rather than during the public spring budget process, the total cuts over that period may surprise many New Yorkers. Since the January 2008 budget modification, the mayor has cut a total of $3.1 billion, or 14.7 percent, from the fiscal year 2010 budget.

The police department has seen an aggregate $391 million cut, or 10.2 percent reduction, since January 2008, and the Department of Education's budget, a $944 million cut or 11.9 percent. Social services, health, youth, aging, parks and homeless services, as well as libraries and cultural institutions, will have taken cuts of 18 to 20 percent over the same period.

The IBO report presents some alternative budget savings. As part of its budget cutback, the police department, for example, planned to delay hiring 1,000 cops, saving approximately $50 million a year.

To avoid cutting the force, one of the IBO options would have police officers work fewer but longer tours, while eliminating 20 minutes of paid "wash up" time and so saving $55 million.

The Department of Education, by far the biggest city agency, will be cut by an additional $306 million (4.1 percent) in 2010 alone. Yet the IBO notes several ways the city could save nearly $300 million. Eliminating public funding for private school student transportation would save $57 million. Increasing the average class size by two students would save $187 million. A four-day workweek for pproximately 40,000 employees would save $33 million

One of the mayor's big budget proposals is the $1 billion savings from restructured contracts with employee unions. As part of that, city workers would pay 10 percent of their health insurance premiums. Most currently pay nothing.

The IBO gives the pros and cons to the proposal. On one hand, proponents argue that it would save the city considerable money every year and reflects current practice in the private sector and increasingly in the public sector. Opponents argue it would burden lower-income employees, with little chance of saving actual health costs.

Raising Revenue

Since the January 2008 Financial Plan, revenue proposals to fill the gap of the 2010 budget deficit have been changing. In January 2008, OMB, looking ahead, projected eliminating the 7 percent property tax rate cut then in place for 2010, while keeping it for fiscal 2009. OMB was warning, 18 months in advance, that there would probably be a tax increase.

As the economy slowed, the mayor shifted gears, and in the November 2008 budget modification proposed eliminating the 7 percent property tax cut earlier -- halfway through the fiscal year, on Jan. 1, 2009. After a brief fight with the City Council, the mayor got his way, although the council refused the mayor's request to cancel the $400 property tax rebate for homeowners.

Moreover, the mayor not only got nearly $600 million of new revenues for fiscal 2009, but the modification eliminated the 7 percent rate cut for the rest of the four-year plan -- as well as eliminating the $400 rebate in future years. That went a long way to fill the 2010 budget deficit -- over $1.2 billion of it. The mid-year tax increases also avoided raising an unpopular tax during the spring of an election year.

The November 2008 budget modification listed two other major revenue options for 2010: increasing sales tax revenues and raising personal income tax rates by either 7.5 or 15 percent. The January 2009 plan drops the income tax option but increases the size of the sales tax option to over $900 million by raising the sales tax rate by a quarter of a percent, extending the tax to more services and items, and dropping the current tax exemption on clothing sales.

In other words, the city's most regressive tax, the sales tax, has become OMB's primary new tax option and somehow increasing the city's most progressive tax, the income tax, gets shelved.

The IBO provides analyses on both options. For instance, extending the sales tax to laundering, dry cleaning and similar services would raise $35 million. Extending it to cosmetic surgical and non-surgical medical procedures would raise $60 million, and imposing the sales tax on capital improvements would raise $200 million.

The sales tax is regressive, of course, because everybody pays the same rate, so the sales tax poses a greater burden on lower-income residents than high-income ones. The city's personal income tax, on the other hand, is at least modestly progressive, with rates ranging from 2.91 percent to 3.65 percent. (The top rate starts at $90,000 of taxable income for joint filers.)

The IBO analyses of income tax options include two versions of a commuter tax. The most familiar is the proposed restoration of the small tax -- 0.45 percent for wages and salaries and 0.65 percent for self-employment, earned in the city -- that existed between 1971 and 1999 until it was eliminated without city input in 1999 by a Republican governor, Republican State Senate and a Democratic State Assembly (controlled by Democrats from the city). Restoration would bring in $715 million.

An alternative, progressive commuter tax, with a rate one third the city's resident income tax rates, would bring in nearly $1.4 billion in 2010. Either of these would have to muster support with the governor's office, State Senate and State Assembly, a questionable proposition.

The mayor's November 2008 reference to income tax options -- since dropped -- included only an across-the-board rate increase of either 7.5 percent or 15 percent. Neither would be progressive, although they would raise a lot of money: $660 million and $1.32 billion, respectively.

The IBO sets out two other options, both of which would increase rates progressively.

The first option is similar to the structure of tax rates in effect during an earlier fiscal crisis, from 2003 to 2005. It would add two new rates to the current four rates. They would range from 2.91 percent to 4.2 percent, with the highest rate starting at $450,000 for joint filers. (The top rate from 2003 to 2005 was 4.45 percent, as it was for much of the 1990s.) That would raise $455 million in 2010. Proponents say this would affect only 4.5 percent of all city resident taxpayers; opponents argue city dwellers are heavily taxed already and those affected might leave the city.

A more progressive option would lower the lowest income tax rates, creating six brackets. They would range from 2.68 percent to a 4.2 percent top rate that, as above, kicks in at $450,000 for joint filers. Proponents argue this makes the rates more progressive and gives a majority of taxpayers a tax cut, while raising an additional $342 million in 2010 because of the two higher rates. Opponents say this would cause some taxpayers with incomes about $1 million, whose average tax increase would be $144,000, to leave the city, thus reducing new revenues.

Poetry, Prose and 'Graphatas'

Along with its 70 budget options, The IBO offers clear, independent, and comprehensive analyses. It seems reasonable to expect the mayor and OMB to do the same. Readers of city budget documents expect to find little poetry. But they do expect prose.

What OMB writes, however, could be called "tablese/graphese." Tables and graphs are the lifeblood of budgeteers, but they generally get an interpreter. (Former Mayor Rudy Giuliani used his electronic pointer at budget briefings with skill and evident joy.) OMB currently gives us numbers, hundreds of pages of numbers. But little else.

The summary to the mayor's January 2009 financial plan -- presumably intended for the City Council and the general reader has in its 63 pages exactly 36 bulleted sentences. Not a single paragraph. What we're left with is tables and graphs, with often opaque headings. ("If the Current 30% Loss in Asset Value Continues, NYC Retirement Systems' Employer Contributions Will Increase by $10.9 billion Through FY 2016 to Cover the Loss in Corpus Value" is typical.) The 19 pages of the summary's Economic Update offer not one sentence of explanation.

The city may catch a big break through the economic stimulus plan that has just been signed by President Barack Obama. Apparently $87 billion of the $789 billion plan will go to states as Medicaid spending relief. Assuming New York State shares those savings equitably with the city, Bloomberg's $1 billion projected federal revenues in the January financial plan may turn out to be an underestimate.

But whatever happens with federal aid, at a time of national and local economic/fiscal uncertainty it would be good to have a dialogue with our elected officials in this city. The effectiveness of any such dialogue begins with the quality of the city's budget reports. More plain English and more usable information - as in the IBO's report -- would be a good start. This is a time for gravatas, not "graphatas."

Meet the Independent Budget Office

Have any questions about the administration’s new preliminary budget? Ronnie Lowenstein of the Independent Budget Office will join Gotham Gazette City Hall reporter Courtney Gross to answer your questions live. Check back here at 2 p.m. to participate.

You can also send your questions by twitter or email them to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

From 2 p.m. to 3 p.m. Feb. 10, Gotham Gazette will host the Independent Budget Office’s director for a live online chat. Lowenstein has been director of the office since 2000 and a staff member since its inception as the city’s independent, nonpartisan fiscal analyst. She will take your inquiries on what is included and not included in the budget, how its proposals could affect you and what the city’s options really are to reduce a gaping $4 billion deficit.

Comment

Fix the Budget

No one ever said you needed to start a multi-billion dollar company or get an MBA to set the city's finances straight.

With Gotham Gazette's help, you can increase spending for education or reinstate the commuter tax from the comfort of your own laptop.

Last month, Mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed a $58.8 billion budget that could slash $1 billion from city spending, increase the sales tax by .25 percent (not to mention broaden it to include clothing, hair cuts and more) and seriously lean on Albany and Washington to pitch in billions of additional funding.

So that's his plan. But what would you do?

Bloomberg overturned the city's term limit so he could have a chance to lead the city through this ever-more dreary recession. With our new budget game, BALANCE, you can bypass the City Council entirely and fix our fiscal woes on your own.

Would you increase spending and raise taxes? How about the personal income tax or tolling the East River crossings? Which departmental cuts do you think are the most severe and should be reversed?

Take the reins, but make sure you end balanced or with a surplus. We're not Washington -- we can't run a deficit.

Once you're done, send us the results and we'll report back on how Gotham Gazette readers would balance the fiscal year 2010 budget.

Keep your home page set here, and we'll continue to update you on how the city's real fiscal plan unfolds between now and when our budget must be approved in June.

Play BALANCE now.

How to Balance the State Budget

The financial meltdown and the recession have thrown state budgets out of whack across the country. Plummeting revenues have given New York State a projected budget gap of $1.7 billion for the current fiscal year and $13.7 billion for the new fiscal year that will begin April 1. The combined deficits of New York and 45 other states through 2010 are predicted to reach a staggering $350 billion, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Meanwhile the recession is taking a toll on people across the state. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers have lost their jobs, their homes or their hopes for a secure retirement or a better future for their children. New York's unemployment rate jumped by a full percentage point in December to 7 percent, the greatest one-month increase on record since 1976. The state has lost 121,000 jobs since its August 2008 job peak. More than 50,000 New Yorkers lost their homes through mortgage foreclosures last year.

As the economic damage ripples out from Wall Street, Gov. David Paterson has proposed drastically slashing state spending. School aid, health care, SUNY and CUNY, child care, program for the elderly, homeless prevention and long-overdue wage increases for social service workers struggling to stay above the poverty line will all feel the effects of the budget ax. While he chops away, though, the governor has steadfastly refused to call for a progressive hike in the state income tax -- an increase that would affect only the most affluent New Yorkers.

For the governor, "shared sacrifice" means that the state's low- and moderate-income families and communities must sacrifice while the fortunate few at the top, who benefited the most from the tax cuts of the last 15 years and from this decade's economic growth, will emerge from the budget largely unscathed.

Too Much Spending -- or Too Little Revenue?

Anti-government voices have mounted a steady drumbeat calling for steep budget cuts, ostensibly to rein in "out of control" state spending. The reality? State spending has increased to fund important new commitments such as providing medical care to people without health insurance and aiding urban school districts with high concentrations of children from poor families. The state government also dramatically expanded spending on property tax relief and acted to partially undo years of underinvestment in mass transit and public higher education.

Aside from these major commitments—all supported, by the way, by David Paterson when he was a state senator and lieutenant governor--state spending from 2004 to 2008 grew at less than 2.9 percent a year, barely the pace of consumer inflation.

What the state failed to do, however, was provide the revenues needed to finance such initiatives through the ebbs and flows of the business cycle. Much of the state's current budget crisis might have been averted had the state reversed even part of the tax-cutting spree carried out from 1994 through 2000. All tolled, these cuts now reduce the state's tax revenues by about $20 billion a year, an amount that would erase even the huge projected budget gaps of $17 billion for 2011 and 2012.

Less Pain, More Gain

Like the other 49 states, New York has to balance its budget in both good times and bad. Facing a sizable budget gap during a recession, states have only bad choices. Neither cutting spending nor raising taxes eases the downturn.

Many economists, however, point out that it is less harmful to the economy to raise taxes in a way that limits its effects largely to high income people than to cut state spending that mainly benefits low- and moderate-income people or that pays the salaries of teachers, police officers and other civil servants. In December, 120 economists from across the state sent a letter to Paterson saying, "Economic theory and historical experience [show] it is economically preferable to raise taxes on those with high incomes than to cut state expenditures."

This is because high earners typically spend only a fraction of their incomes in any given year, saving the rest. On the other hand, state spending goes to pay workers, provide services and put money in the hands of New Yorkers in need. This means the money goes directly into the economy, priming the pump at a time when it is desperately needed. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University made the same point in a letter to the governor last March.

Public opinion across the state strongly favors increasing income taxes on high earners over cutting spending for health care and education. The governor, though, has argued that raising taxes on the wealthy will drive them from the state.

No evidence exists to support that claim. In 2003, New York temporarily raised its top income tax rate from 6.85 percent to 7.7 percent. During the three years that this increase was in effect, the number of high-income returns grew significantly. This experience in New Jersey, which permanently raised its top personal income tax rate to 8.97 percent in 2004, has been similar, according to a Princeton University study.

Beyond a High-End Tax Hike

Paterson and the two top legislative leaders -- Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith -- have committed to closing the projected $1.7 billion budget gap for the current fiscal year by Feb. 4, even though the year does not end until March 31.

What should they do? In addition to its investments in infrastructure, unemployment insurance modernization and other measures, the massive economic recovery bill now making its way through Congress includes aid, called “state fiscal relief,” for the explicit purpose of helping states balance their budgets without putting too much additional drag on the economy. Since this legislation is likely to go to President Barack Obama for his signature in mid to late February, the sensible course would be for Paterson and the legislature to wait to see exactly how much “budget balancing” aid New York will receive under the final legislation. The chances are excellent to certain that the state will get several billion dollars it can use right away, since important parts of the “state fiscal relief” is retroactive to Oct. 31, 2008.

In the unlikely event that the immediate “state fiscal relief” does not close this year's gap, the governor has already identified at least $600 million in various reserve funds that could be tapped to balance the books. On top of that, the state has at least $1 billion in its Tax Stabilization Reserve Fund that it could us if needed. Even if it had to borrow against that -- which seems unlikely -- the state still has $400 million in a newer "rainy day" fund as well as a few hundred million in other reserves.

Closing the projected $13.7 billion gap for the 2010 fiscal year will prove more difficult. A progressive tax increase would generate roughly $5 billion. This, along with several billion more from an increase in the federal payments for Medicaid or state fiscal relief in the stimulus package will address most of the budget gap.

Some budget cuts may be unavoidable, but the state should also consider closing tax loopholes such as one that benefits non-resident hedge fund general partners working in New York State and taking other actions to generate budget savings. These could include ending the wasteful and failed Empire Zones program, increasing the use of state engineers rather than contracting out that work to expensive consultants, or using the state's sizable purchasing power to get better prices on prescription drugs.

Restoring Tax Fairness

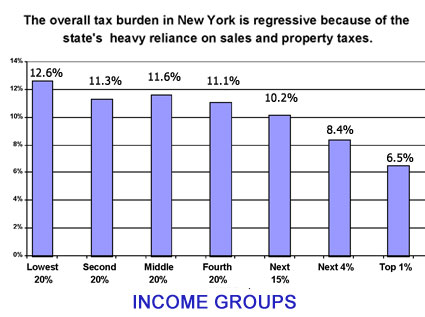

Click here for a larger image

Raising taxes on high earners would also be a step toward restoring fairness to New York's graduated income tax, which has become significantly less graduated over the years. Today, because of the state's increased reliance on regressive sales and property taxes, New York's middle- and lower-income households pay a higher share of their incomes in state and local taxes than the top 1 percent or the top 5 percent (see chart).

Moreover, as astounding as it may seem, data indicate that all of the income growth in New York State from 2002 to 2009 has gone to the wealthiest 5 percent. In 2009, the other 95 percent of households have roughly the same incomes they had in 2002. When you factor in inflation, the combined income of the bottom 95 percent of New Yorkers actually shrunk.