Assembly's Boyland Faces Tough Primary Challenge

William F. Boyland, pictured here in 2005, from the assemblyman's website.

NEW YORK — William F. Boyland Jr., the four-term assemblyman representing the 55th district in Brooklyn, went on what for him might be described as a bill-drafting binge during the legislative session earlier this year — introducing a total of three measures in Albany.

That exercise of his legislative duties contrasted with 2010 and 2011, when he introduced a total sum of zero bills.

But Boyland’s lack of productivity and the fact that he missed one-third of all votes last year — or that he was caught playing the video game Cityville on Facebook rather than preparing for Assembly sessions he failed to attend — are the least of the reasons why he is facing the greatest challenge to his control of the seat he virtually inherited from his father in this Thursday’s primary. After all, none of those foibles carry with them criminal charges.

Boyland was arrested on federal bribery charges in Brooklyn in November 2011, about three weeks after being acquitted in a separate Manhattan case. Prosecutors allege that Bolyand tried to solicit more than $250,000 in bribes, some of which was intended to pay for the attorneys in the Manhattan case.

Boyland pleaded not guilty to the charges outlined in the second bribery case.

The Albany County district attorney and the state controller are also investigating Boyland in two separate cases involving travel expenses and state-issued credit cards.

The assemblyman did not return phone calls from the Gazette requesting comment about the allegations or the primary.

The Boyland family has been referred to as the “Kennedys of Brownsville,” and have been in power in the district since the 1970s, when Thomas Boyland, Assemblyman Boyland’s uncle, was first elected to the state Legislature in 1977. Boyland Jr. currently occupies the seat his father relinquished in 2003 after a 21-year career.

Even with the charges hanging over his head, one of the biggest hurdles Boyland’s six challengers face are each other, since they could ultimately split the vote, helping the well-known incumbent.

This year’s challengers include Tony Herbert, who works as a vocational education specialist at a shelter for homeless women who are mentally challenged; Roy “Uncle Roy” Antoine, the owner of a local clothing store; Anthony Jones, a former youth counselor and long-time resident who was close with the late Councilman James Davis; Nathan Bradley, who serves as both Community Board 5's chair and as a deputy chief of staff for state Sen. John Sampson; David Miller, a member of Community School Board 16; and Christopher Durosinmi, aide to state Sen. Martin Dilan.

Only Herbert could be reached for comment. “The Boyland name has come under serious fire and I don't think they're going to survive this,” Herbert said, referring to the bribery allegations brought against Boyland. (Citizens Union, the sister organization of Gotham Gazette, has endorsed Herbert.)

Herbert maintains he has far more legislative experience than the other candidates, including Bradley and Durosinmi, each of whom works for a different state senator. He notes that Boyland follows the Democrat Party line, and while he said he "respect[s] the ideology of the Democrats," he says "the purpose of office is to serve the people," not to be a "party hack."

While generally critical of Boyland on the issues, Herbert says the lack of banking options in the district is particularly frustrating, given that the assemblyman serves on the housing, economic development, local government, banking and aging committees. Boyland is also the chair of the subcommittee on senior outreach and activities.

On his website, Boyland emphasizes his support of efforts to stem crime, including the DNA databank expansion that passed earlier this year.

“Ever since its inception, DNA evidence has revolutionized criminal investigations, helping solve thousands of cases that might have gone unsolved without it,” Boyland said in the statement. “By expanding our offender DNA databank, we will help our police officers and local officials solve more crimes and put dangerous criminals behind bars.”

The district, predominantly composed of much of Brownsville and Ocean Hill, as well as parts of Bushwick, Crown Heights, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and East New York, is among the densest in the state, due in no small part to the number of housing developments within its boundaries.

According to New York City CompStat reports, precincts in the district remain among the highest for crime in the city. Further, about half of all residents receive some form of assistance such as social security's supplemental security income, welfare or Medicaid, and the district is among the highest in foreclosure rates and lowest in high school graduation rates, according to official studies undertaken by the state.

There's a lot of work to be done in the district that's just not getting done, Herbert said, adding that the date of Boyland’s upcoming trial is “extremely problematic.” If Boyland is found guilty, it could undercut “the democratic process,” he said. Boyland’s trial is scheduled to begin three weeks after the primary.

Herbert said a guilty verdict in Boyland’s most recent case would deprive the voters of a chance to pick their appointed official because the Brooklyn County Democratic Committee would end up deciding who would fill the district seat.

It is also unclear where Boyland is getting the money to finance his campaign. Boyland's three fundraising committees have been sued over 40 times by the state for failure to file financial information relating to his campaigns, said John Conklin, a spokesman for the Board of Elections. All told, the suits tally approximately $23,000 in fines.

Of Boyland's three committees, the Committee to Re-Elect William F. Boyland, Jr., hasn't submitted a filing since 2009, but remains active according to the BOE website; Friends of William F. Boyland Jr. filed a 'no activity statement' in July 2012, its first filing since 2009; and the William F. Boyland Jr 2010 Re-Election Campaign, though still active, has not had a report filed since 2010.

Conklin said the state can only go after the treasurer of a committee after it is closed. “We've done everything we can do under the power of the law,” he said.

___

Matt Hunger, a Brooklyn-based freelance journalist, writes on everything from municipal issues to the arts and sports. He can be reached at matt.hunger(at)gmail.com.

Family Values at Play in State Senate Race in the Bronx

Photo by David Howard King

ALBANY, N.Y. — Maybe it was state Sen. Gustavo Rivera’s vote for same-sex marriage. Perhaps it was that Rivera backed state Sen. Adriano Espaillat’s run against U.S. Rep. Charles Rangel. It could also be that Rivera unseated Ruben Diaz Sr.’s fellow amigo, convicted state Sen. Pedro Espada, in the 2010 race.

Whatever the impetus, Diaz has been giving Rivera’s little-known challenger for the 33rd State Senate District, Manny Tavarez, the support of his formidable ground operation in the run up to Thursday's primary. That operation includes a slew of vans and trucks equipped with loudspeakers that blast slogans and campaign workers that move through the Bronx handing out stacks of literature.

Diaz Sr., also may have given Taverez financial support as well, but it is impossible to know because, as of press time, Tavarez hadn’t filed any campaign finance documents with the state Board of Elections.

"It's not surprising that he has endorsed my opponent, given that he worked closely with my corrupt predecessor,” Rivera said of Diaz’ support for Tavarez.

Rivera does have the support of another Diaz: His son. Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr., is seen as more progressive than his father, and has endorsed Rivera and made public appearances with him; the two have also worked together on a health initiative. Rivera told the Gazette earlier this year that the borough president was his “hero” when it came to fitness and health.

Yet the same political machine that includes the fleet of vans and dozens of campaign workers that have worked in the past to get Diaz Jr., elected are now supporting Tavarez — and, in the Bronx, that alone might make the difference in the challenger’s effort to unseat Rivera.

Neither Diaz Sr., nor his son responded to emails and phone calls requesting comment for this story over the past week. Tavarez also didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Diaz, father and son, have kept a distance from each other in the public eye.

Diaz Sr., is seen as an old-school machine politician who blurs the lines between his status as a reverend and as an elected official.

That army of vans that Diaz has are housed at his church the Christian Community Neighborhood Church and, during election season, Diaz hosts block parties across the Bronx that are sponsored by his church. The parties gather groups of citizens that are then targeted by Diaz’s get-out-the-vote team. The Christian Community Benevolent Association, which owns the church, has been a major beneficiary of Diaz’s status as a senator.

In fiscal year 2006-2007, Diaz was able to steer nearly $500,000 in member items to the CCBA. In May of this year, the financial officer for the CCBA was accused by prosecutors of embezzling $75,000.

Diaz also hasn’t exactly been a team player when it comes to being a Senate Democrat. In 2008, Diaz joined with Sens. Pedro Espada, Carl Krueger and Hiram Monserrate to hold the senate majority hostage for more power. It wasn’t clear if Democrats would have a majority heading into session that year. Later, when Monserrate and Espada joined Senate Republicans and created the Senate coup, Diaz remained a Democrat but also stayed very friendly with the defectors.

Since then, Diaz has watched as Monserrate, Espada and then Krueger were either drummed out of the Senate or convicted on federal corruption charges. Rivera was able to defeat Espada in the 2010 Democratic primary before Espada was convicted. Diaz told The New York Times that he felt then-Attorney General Andrew Cuomo overreached in his charges against Espada and that it was part of a “vendetta” for the coup.

Diaz gnashed his teeth and stomped his feet while the Senate passed same-sex marriage in 2011, cursing fellow party members who voted for the bill and telling the Republicans they should be ashamed of themselves for even allowing such a vote.

His son, on the other hand, has projected an image of a new school Democrat and a team player. He has very publicly disagreed with his father’s belief that there should be no separation between church and state and his sometimes vicious attacks on homosexuals.

“We have an agreement,” Diaz Jr. told NY1 in 2009. “He doesn't tell me how to be borough president, I don't tell him how to vote in Albany.”

The gay community has been critical of Diaz Jr., for not speaking up loudly against the vitriol his father has spit at the community.

Ken Padilla, a Bronx district leader who went from working with the Diaz’s to waging a public battle with them, says that he has never seen much separation between father in son when it comes to political decision-making.

“For the two years I spent working with them, the two made major decisions in the same room,” he said. “The father would never do anything without consulting the son. He would never do anything to hurt his son’s political career.”

Padilla filed an IRS complaint against Diaz for storing his campaign vans at his not-for-profit church.

So while Junior may be publically supporting Rivera, Padilla says he thinks what really matters is Senior’s endorsement of Tavarez — which comes along with an entire political organization.

“Junior may be going along with the party line and supporting Rivera, but it is the organization, the structure, the people, the vans that matter and the father controls that,” Padilla said. “Senior’s support comes along with the vans and the people. It’s the same people, the same vans for junior and senior.”

BOE spokesman John Conklin said that Friends of Manny Tavarez was formed on April 19, 2012, and has not filed any financial statements with the board since then.

The committee should have filed a July periodic statement and a 32-day pre-primary statement.

Conklin says the board has sent multiple letters to the campaign asking that it show cause for failing to file and has begun the process of suing the committee.

Born in Rochester in 1979 to Dominican parents, but raised in the Bronx, Tavarez previously worked for District Leader Hector Ramirez’ unsuccessful campaign in 2010 for the 86th State Assembly seat (Nelson Castro, one of Rivera’s supporters, won that race), according to his website. The website also says Tavarez had experience during City Councilman Fernando Cabrera’s campaign in 2009. Before local politics, he was involved in baseball academies in the Dominican Republic.

On his website, under a section entitled “family values,” a message reads: “Manny Tavarez is pro-life. He believes that life begins at conception and wishes that the laws of our state reflected that view. Taking innocent life is always wrong and always tragic, wherever it happens.”

Rivera, on the other hand, is a member of the Bipartisan Pro Choice Legislative Caucus of the state Senate.

Second-Longest Running Show Now on Broadway is Uptown

Photo of voters in Washington Heights/Andy Humm

NEW YORK — The second-longest running show now on Broadway is not in the Theatre District, but uptown in Washington Heights.

In this sliver of a neighborhood on Manhattan’s upper Upper West Side, Broadway is the high street in the Dominican American community — and there hasn’t been a curtain call in over two decades on the rivalry between Guillermo Linares and Adriano Espaillat since both ran for City Council in 1991.

Linares won to become among the first Dominicans elected to public office in the U.S.

El Diario/La Prensa columnist Roberto Perez calls this rivalry “the Washington Heights version of the Hatfields and the McCoys.” He also wrote that their late August debate at the Hamilton Heights Social Club Los Bravos “felt more like a cockfight arena than a forum.”

On Thursday, Sept. 13, the two men square off against each other in yet another Democratic primary — this time for the state Senate seat that Espaillat holds.

Linares gave up a run for his Assembly seat to seek the Senate seat that Espaillat was giving up to challenge incumbent Charles B. Rangel in the newly-drawn and newly Latino-majority 15th U.S. Congressional District.

Rangel, with Linares’ support, won that race by a hair — just 990 votes — in a rare June primary that was rattled by questions over the balloting. Following his loss, Espaillat decided to try to keep his Senate seat in the separate September primary. (Full disclosure: I did some work last spring writing campaign literature for the Rangel campaign.)

The new 31st State Senate District hugs the east bank of the Hudson like Chile does the Pacific, covering Inwood to Hell’s Kitchen (with a few blocks of Chelsea thrown in) — but its heart is still Dominican Washington Heights.

It had been Eric Schneiderman’s district until he ran successfully for state Attorney General in 2010 when Espaillat won a three-way primary for it.

Espaillat has the distinction of being the first Dominican American elected to the State Assembly in 1996, knocking off longtime incumbent Brain Murtaugh in a primary.

He also fended off a strong challenge from Miguel Martinez, a former ally, in 2008. (Martinez served in the City Council from 2002-09, when he resigned amidst a conspiracy scandal in which he was ultimately convicted.)

Linares served in the Council from his historic election in 1991 until he was term-limited out in the 2001 election. He was appointed by Mayor Bloomberg as Commissioner of Immigrant Affairs in 2004, where he served until taking the Assembly seat that Espaillat gave up to run for the state Senate.

Bloomberg pledged to back Linares’ current campaign by raising $100,000 for him.

Espaillat and Linares debated on Manhattan Neighborhood Network on September 4. In the debate sponsored by the League of Women Voters, they tended to agree on most issues, while attacking each other over their commitment to stronger rent laws and the failure of the state to adopt nonpartisan redistricting this year.

Espaillat said, “I believe very strongly this primary [by Linares] is being bankrolled by the landlord interests. My opponent has received $40,000 from the landlord lobby to push me out.” Linares did not dispute the donation.

On tenant issues, Linares said that as a City Council Member in 1997 he “was one of the few who stood up to the Speaker to prevent vacancy decontrol,” which was approved in the Assembly with Espaillat’s vote and virtually every other pro-tenant member as part of the renewal of the rent laws that the Republican Senate would allow only in that weakened form.

Espaillat takes credit for getting the rent laws renewed in 2012. “For the first time, we were able to pass slight improvements,” he said.

Linares told Gotham Gazette that, as landlords try to renew their J-51 tax break this year, he will insist on “strengthening of the rent laws and eliminating vacancy decontrol” as part of the bargain.

Nevertheless, Tenants PAC, which endorses candidates based on their commitment to tenants’ rights, is going with Espaillat in this race, calling him “a major player in the fight for stronger rent laws and the preservation of affordable rental housing.”

At the cable TV debate, Linares cited his endorsements from Councilman Robert Jackson, State Senator Tom Duane, former Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger, former Councilwoman Ronnie Eldridge and former Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum.

Espaillat cited support from Congressman Jerry Nadler, Assemblyman Dick Gottfried, Assemblywoman Linda Rosenthal, Citizens Union (the sister organization of Gotham Gazette) and Tenants PAC.

Linares has District Council 37 of American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees; Espaillat has the United Federation of Teachers, 32BJ SEIU, the Working Families Party, and the Hotel Trades Council.

The split between the opposing political camps is long and deep.

Moises Perez, a longtime community leader and the former director of the now shuttered Allianza Dominicana social services center in the district who managed Rangel’s re-election bid, said it doesn’t stem from a dispute over the issues. “It’s about political ego,” he said.

The men have competing political clubs — Linares’ Concerned Democratic Coalition of Northern Manhattan and Espaillat’s Northern Manhattan Democrats for Change.

There was a brief peace between the two in 2010 when Espaillat ran for Senate and Linares for Assembly without running opponents against each other.

“The community would rather see us working together,” Espaillat said. “[Linares] wants to run against me for Senate. Wants to impose his daughter for the seat he left behind. This is not a blueblood district — the royal kingdom where titles are passed by sons and daughters. There are plenty of people with leadership qualities in the community.”

Both men are tenacious, though Linares is more low-key and seemed to be waiting his turn to run in 1991 and saw Espaillat as jumping the gun by challenging the longtime incumbent Stanley Michels in 1989.

“When we faced off in 1991 [for City Council], I had been serving this neighborhood for 15 years,” Linares said. “I have been an activist since I landed here as a teacher.”

Espaillat countered: “He is a go-along kind of politician.” Linares said: “In order to represent all groups and constituents, I had to earn their respect.”

He also added that he stuck with Rangel over his fellow Dominican because the longtime congressman “is an ally of our community” who he has worked with for years.

Both men took Ed Koch’s pledge not to vote for a redistricting plan for state legislative districts unless it was independent and nonpartisan.

When Senate Republicans reneged on their promise to Koch to take politics out of the process and Gov. Andrew Cuomo decided not to put up a fight over it, Espaillat was among those who walked out of the chamber during the vote on the partisan lines that added a 63rd State Senate District designed to help the Republicans hold the slim majority they regained in 2010.

Espaillat attacked Linares for voting for the redistricting plan — as most Assembly Democrats did. Linares countered that he is “fully supportive of an independent commission” to draw the lines and attacked Espaillat for voting for the partisan lines 10 years ago as an Assembly member.

Linares said his priority as Senator will be passage of the New York DREAM Act to “allow undocumented students who meet in-state tuition requirements in New York to access state financial aid for higher education,” according to the bill’s website.

It passed in the Assembly but was “dead on arrival” in the Senate, Linares said, a status that is unlikely to change unless Democrats can re-take the chamber.

While the Senate race is the main event, the undercard Assembly contest is almost a proxy fight for the two men. One candidate is blessed by Espaillat — Gabriela Rosa, a member of Community Board 12 and a senior policy advisor to Assemblyman Denny Farrell; while another is backed by Linares — his daughter Mayra Linares, a community activist, district leader and recent aide to Cuomo.

The voters could instead opt to go an independent route by electing either Melanie Hidalgo, a member of Community Board 12, or perennial candidate and community activist and career Air Force veteran Ruben Dario Vargas.

A debate among the four Assembly candidates at the Centro Cultural Deportivo Dominicano on Amsterdam and 163rd Street, founded in 1966, drew more than 200 people for a high noon Spanish-language showdown on a beautiful Saturday in the middle of Labor Day weekend. It began with the playing of the national anthem.

Three of the candidates — Linares, Rosa and Vargas — squared off in an MNN cable debate as well. While most spoke in generalities about the issues, on mayoral control of the schools, Linares came out in favor of “more involvement of parents.” Vargas was in favor and Rosa was opposed to the system of governance that began under Mayor Bloomberg.

Rosa said she would be “independent and a team player.” Vargas said: “We have to stop people being selected by political machines because their hands are tied.” And Linares replied, “It is important to have relationships and know how to work with others.”

Trying to stick it to Linares, Rosa said: “Mine is a community candidacy, not inherited.” Linares said she has been involved in the community since she was “5 years old handing out fliers.”

Mayra Linares told the Gotham Gazette that she was “born and raised in this community” and has lived in three of its neighborhoods — Washington Heights, Marble Hill and now Inwood. She was attacked by her opponents for taking landlord money; but, like her father, she promises to support tenants “100 percent.” Tenants PAC is backing Rosa.

No poll has been released in the two races, but some prognosticators gave Espaillat the edge in the contest over the Senate seat because he has just come off a high-profile tussle over Rangel’s spot in Congress. Mayra Linares is seen as the favorite in the Assembly race simply because of her name.

Whatever the outcome, the battles of Washington Heights show no signs of letting up any time soon. In a city where incumbents are rarely subjected to serious challenges, the voters uptown almost always get lively, competitive races.

UPDATE: An earlier version of this story said that Espaillat vowed during his Congressional race that he would not try to keep his Senate seat if he lost. Ibrahim Khan, a spokesman for Espaillat, said the candidate never made that claim.

_____

Andy Humm is the co-host of the weekly Gay USA cable TV show, a contributor to Gay City News, and a former city Human Rights commissioner.

5 Primary Races Worth Caring About

Not alluring enough to grab the attention of most voters, primary elections are often ignored by all but the most politically engaged.

But with financial scandals, rivalries and allegations of bribery in the background this year, the state’s legislative primaries, being held on Sept. 13, are definitely worth paying attention to.

We’ve picked the top five worth caring about — as much for their drama as for their political gravitas.

The Rivalry: 31st State Senate District

Sen. Adriano Espaillat wasn’t planning on running for his old state Senate seat, but his challenge to U.S. Rep. Charles Rangel didn’t go the way he wanted.

Now Espaillat faces his longtime political rival Assemblyman Guillermo Linares in a race for the 31st State Senate District. The history between the men dates back to the early 1990s, when Linares defeated Espaillat for a seat on the City Council. It’s likely that election reform will be on Espaillat’s mind should he be reelected; a number of irregularities took place at the Board of Election during his challenge to Rangel.

Both Linares and Espaillat take pride in their Dominican roots and have been active on workers’ rights. Espaillat enjoys the support of a number of Linares' Assembly colleagues and most of the Senate Democratic conference. Not every state Senate Democrat has lined up to back Espaillat — retiring Sen. Tom Duane served on the Council with Linares and has endorsed him. Meanwhile, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has gotten involved in fundraising for Linares.

The Missed Opportunity? 55th State Assembly District

William Boyland should be in the fight of his life for his 55th Dstrict Assembly seat.

The assemblyman beat bribery charges only to be quickly indicted again on federal bribery charges after prosecutors say he solicited cash from an undercover FBI agent. Boyland also managed to go a full year without sponsoring any legislation and has one of the highest absentee rates of any legislator. Boyland is the poster boy for machine politics and Albany dysfunction.

However, Boyland faces eight challengers in the primary. It’s unlikely all of them have mounted full campaigns, and having that many names on the ballot will likely split the vote.

The Boy-Toy Scandal: 80th State Assembly District

The Democratic incumbent in the 80th State Assembly District is Naomi Rivera, the daughter of a storied Bronx political family. Her main challenger is real estate agent Mark Gjonaj, a favored son of the borough’s Albanian community, as well as a commissioner of the Taxi & Limousine Commission.

What was supposed to be a lukewarm contest became a whole lot more interesting in recent weeks after a certain New York tabloid began detailing allegations of how Rivera had hired an ex-boyfriend to run her taxpayer-funded nonprofit.

More allegations of nepotism followed, which were then followed by reports that the state ethics commission was investigating Rivera’s actions and that the city’s Department of Investigation was also looking into her hiring practices. Rivera has denied the allegations, but the storyline has stuck.

In Office, In Handcuffs: 10th State Senate District

In conversations earlier this year, a number of those involved in the Senate Democrats' efforts to reclaim the senate majority made it clear that they expected a few “new faces” in the conference.

Although not made explicit by them, the fact that they accepted the idea that a number of their sitting colleagues would be defeated in the primary very easily could have come from concerns lingering over a number of their candidates.

The 16th State Senate District was very likely on their list of districts.

Reports about investigations into Huntley’s nonprofit popped up periodically for months until a few weeks ago, when Huntley held a weekend press conference to announce that she expected to be arrested. Huntley has been charged with aiding a conspiracy to defraud the state and forging documents sought in an investigation.

Huntley’s campaign seemed to already be in trouble as they announced a number of endorsements they had not actually won. Meanwhile, Councilman James Sanders is a strongly financed candidate. The state redistricting process actually made a good section of Sanders’ council district — where he is well known — a part of Huntley’s newly drawn district.

New District, New Legislator? 16th State Senate District

Sen. Toby Anne Stavisky has spent 13 years in the Senate representing Queens — and, if it's up to John Messer Stavisky, she won’t be there for one more year.

The pair are running for a new seat redrawn under the redistricting process to ensure strong representation for Asians. Stavisky’s family had controlled Stavisky’s old seat for decades but she would have had to primary against Sen. Tony Avella to keep it, thanks to redistricting.

The new district is made up of 53 percent Asians and does not include the Bay Terrace Area — a section of Queens that has traditionally been Stavisky’s stronghold. Messer has touted his connection to the Asian community and accused Stavisky of ignoring the concerns of the Asian population in Queens. Messer has also donated hundreds of thousands of dollars of his own cash to his campaign.

Stavisky, however, has the backing of the establishment, including Sens. Chuck Schumer and Kirsten GIllibrand, as well as the majority of the city’s Asian politicians. Messer ran against Stavisky in 2010 and finished third.

How the State's Political Scandals are Reshaping the Primaries

![]()

ALBANY, N.Y. — On Sept. 13, 2012, when voters go to the polls to pick candidates in the state’s legislative primaries, it is possible that the status quo will prevail.

Incumbents who rely on the support of the system they control, buttressed by the largesse of major businesses and wealthy donors and the general apathy of a disengaged electorate, may find themselves coasting to an easy victory against upstart challengers. Or not.

A series of sordid scandals gripping the New York State Legislature over the past few weeks could lead to a surprisingly different outcome.

Just over a week ago, it was revealed that the Assembly cut an over $100,000 publicly-funded deal with two women who claim to have been sexually harassed by one of their most influential colleagues, Brooklyn power broker Vito Lopez. The 71-year-old Democrat was stripped of his seniority in the Assembly, his committee chairmanships, his staff funding, and is not allowed to employ anyone in his staff under the age of 21. The fallout continues everyday and is now likely to lead to an investigation of Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver’s handling of the case.

Also enmeshed in her own scandal is Queens Democratic state Sen. Shirley Huntley, who was arrested on federal fraud, forgery and conspiracy charges last Monday in connection with a scheme that bilked the state of $30,000 in cash directed to the nonprofit she founded.

Huntley’s opponent in the Democratic primary, City Councilman James Sanders Jr., says people have told him he should be celebrating.

“People were saying how I should be happy in her declining fortunes. I think it is actually sad to see an elder in handcuffs," he said. "Little kids really look up to us. We should never do anything to break the hearts of children.”

Two other Assembly members up for re-election have been caught up in political drama: In the Bronx, Assemblywoman Naomi Rivera stands accused of giving cushy political jobs to her lovers; and, in Brooklyn, Assemblyman William Boyland, got off one set of bribery charges only to find himself indicted again after prosecutors say they caught him seeking bribes to pay off his legal bills.

None of the political office holders involved in the scandals responded to requests for comment for this article. A call to Huntley’s number was greeted by the echoing sound of a dial tone after introductions were made.

Challengers See Hope in Incumbents' Scandals

While Huntley’s arrest was dramatic and the accusations against Rivera arousing, Brooklyn boss Lopez was such a powerful figure in New York politics that the scandal could carry over to his allies.

That is certainly what Jason Otaño hopes. Otaño, who served as general counsel to Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, entered the race against Sen. Martin Dilan knowing that the incumbent was backed by the Lopez political machine. Now that the Lopez scandal has blown up, Otaño hasn't been shy about underscoring the connection between Dilan and Lopez.

He called the Dilan political clan which includes the senator and his son Councilman Erik Dilan "a wholly owned subsidiary of Vito Lopez."

"When Vito says 'jump,' the Dilans say: 'How high?'" Otaño claimed.

Otaño is an ally of U.S. Rep. Nydia Velazquez — a political opponent to Lopez and Dilan. “I looked at the entirety of the political structure in North Brooklyn and planned [on] running for City Council," he said. "But I felt we weren’t doing enough for the reform movement."

Erik Dilan challenged Velazquez in a primary earlier this year and she is backing just about all the candidates running against Lopez’s favorites.

Dilan’s office did not return calls requesting an interview.

Dilan faces the same trouble most of his Senate allies do — their record of legislative achievement. Democrats squandered a chance to enact major pieces of their agenda when they held the majority and, since they lost it in 2010, they have been pushed into irrelevancy by the Senate Republicans, the Independent Democratic Caucus and Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who avoids them like the plague. Cuomo’s avoidance of them could have to do with the taint of scandal. But Otaño sees himself as part of the solution to the Senate Democrats' problems.

“I believe it is no secret to anybody that Albany is a mess," he said. "The Legislative process is really at issue. My opponent refused to work toward legislation that really benefits constituents who are priced out of their homes, Latinos who have been displaced. That has all been enabled by loopholes in legislation.”

The failure of Democrats to champion stronger pro-tenant legislation has haunted them since Sen. Pedro Espada chaired the housing committee and, in the view of most housing advocates, intentionally blocked pro-tenant legislation to cow tow to his major donors in the real estate industry. “Someone in this district should be a leader on these issues,” Otaño said. And Otaño has the backing of Tenants PAC, an organization that has mobilized a number of its members to knock on doors for the candidate.

Sanders also believes his opponent didn’t do enough as a member of the Democratic caucus to deal with housing issues and help her district. “The real issues are gun violence, the lack of jobs, the great recession caused havoc [in] our community and predatory lenders have focused on our community," he said. "The people of this district have been failed by government on all levels.”

Cleaning Up the Democratic Party

Sanders says the state Democrats need a makeover. “I am part of the clean team.” Otaño also thinks the next generation of politicos are ready to clean up the “mess.”

“I do believe we have a great young crop of individuals involved in public service who are ready to take the machine to task — people like Jesus Gonzales and Lincoln Restler,” Otaño said.

Restler has been challenging Lopez’s power on the county level, while Gonzalez ran for the Assembly seat vacated by Ed Towns last year.

Gonzalez, a community organizer, faced Ed Towns' daughter and Raphael Espinal, who worked in the Council office of Erik Dilan, and had a number of staffers working for him who were also on the payroll of Martin Dilan. Of course, given the Dilan family's association with Lopez, Espinal almost assuredly had the Brooklyn power broker's backing — and won the race soundly. But Gonzalez made such an impression that he was encouraged to run for Council in 2013.

“Young, insurgent, upstart” was a phrase used to describe now-incumbent Sen. Gustavo Rivera two years ago when he challenged and defeated scandal-ridden Sen. Pedro Espada — the man behind the 2009 Senate Coup.

While Espada was eventually convicted on federal charges for stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars from the publicly-funded health clinic he ran, he lost his seat to Rivera long before those charges were brought.

This year, Rivera is facing a primary challenge from Manny Tavarez. The primary is largely seen in political circles as payback from the camp of Rep. Charlie Rangel for Rivera’s backing of Rangel’s primary opponent, Sen. Adriano Espaillat.

Tavarez didn’t return calls for an interview request. Rivera refuses to comment on his opponent’s motivations, but he says he is excited to have a challenger.

“I don't know why the gentlemen is running, but I welcome it as a chance to talk about what we’ve done and get out there in the community," he said. "I've been available, accessible, so I think people know me.”

Rivera says he is tired of hearing about what Democrats could have done when they were in the majority. “That is a tired argument," he said. "This is a completely different conference.”

It’s unclear how much damage the recent scandals will do to incumbents in the primary and Democrats in the general election.

“Everyone has seen that movie where the good guy is fighting the vampire and he knocks 'em down and turns his back and the audience is screaming â€You gotta drive a stake through its heart!’ Well, I plan on driving a stake through this election,” says Sanders. “We are going to continue knocking on doors. The real threat is apathy. People say all politics is corrupt. If you think none of the above are worth voting for, then you should run.”

Campaign Committees Operate With Little Oversight, Groups Say

ALBANY, N.Y. — Modest, crunchy former Green Party gubernatorial candidate Howie Hawkins might not be the first name that comes to mind when you think of the word scofflaw.

In Hawkin’s case, his committee hasn’t filed reports since 2011 and, even though it’s allowed to file a no-activity statement, it hasn’t, according to campaign finance records. Records also show that Hawkins 2010 campaign committee has $12,906 on hand, though Hawkins says the real number is a lot lower.

“My treasurer was a volunteer who just got overwhelmed,” Hawkins explained. “She said we had $12,000 on hand, but we have about $1,000.”

Campaign committees have long operated without much scrutiny from the public or regulators, including by the state Board of Elections, which is charged with overseeing them, according to good government groups.

The groups say the BOE’s enforcement is so lax that the only action they take regularly is issuing relatively small fines that range from $100 to $1,000 to those who don’t file on time. They also say that the BOE is not even trying to catch major offenders like corporations that routinely donate money well over New York’s already extremely high contribution limits.

As the state heads into the peak of election season, campaign committees are being scrutinized anew.

Last week, the New York Public Interest Group released a study that aimed to highlight the failure of BOE enforcement actions, showing that 2,328 campaign committees had failed to file activity reports for the July period. Hawkins’ name appears on that list right along with disgraced former state politicians Pedro Espada and Hiram Monserrate.

NYPIRG - $31M in Campaign Funds Missing in ActionThe BOE disputes the assertions of good government groups, arguing that it has been aggressive in enforcing campaign finance laws.

“Since 2006, we have initiated 5,042 lawsuits against candidates and committees seeking more than $1.5 million in court-assessed fines for failure to file campaign finance disclosure reports,” the BOE said in a statement. “While we are criticized for seeking fines of only $1,000, that is the maximum allowable under current law. In addition, we average more than 4,000 enforcement actions each year, which stop short of litigation because the committees or candidates make their filing.”

The BOE also said it had referred more than 900 cases involving candidates and committees to the Albany County district attorney between 2007 and 2010.

Hawkins said the BOE has routinely notified him and his treasurer of deadlines. He said he is currently trying to figure out the accounting mess and file with the BOE.

“In my experience, they fine you, and for the little guy $500 is a lot, it hurts. But in some ways it’s inexcusable,” Hawkins said.

Bill Mahoney, legislative operations and research coordinator for NYPIRG, agrees that the current system is harder on the little guys. He also says he is aware of a number of candidates who were being fined and didn’t even know it because their treasurers had moved, retired or had other problems.

“They sent notices to old addresses, issued fines and didn’t even follow up as to why they hadn’t filed,” Mahoney said. He also noted that the regulations the BOE enforces are frustratingly lax.

“We’ve come to a point where you have to be walking away with the money and not telling anyone for it to be illegal,” he added.

New York has the laxest limits on campaign contributions of any state in the nation. The state BOE is overseen by two Republicans and two Democrats who need three out of four votes to take significant enforcement action. Good government groups think the BOE routinely avoids going after the big fish because it doesn’t suit them.

Two Freedom of Information Law requests made by NYPIRG to the BOE show that the only enforcement actions taken by the BOE since 2007 for violations of the campaign finance laws were fines for late filings ranging from $100 to $1,000.

"An examination of committees that haven’t filed recently shows that even in this area, the Board has not met its responsibilities to enforce the law,” the NYPIRG study says. The report also asserts that more than 2,300 committees — which have collected more than $31 million — "have still not disclosed any transactions made during the six months covered by the July filing period." Many of those same committees haven’t filed required disclosure information for more than a year.

NYPIRG routinely evaluates corporate donations and sends the BOE a list of apparent violations — donations that are over the limits, missing addresses of donors, missing names and so on.

Letter to BOE 11 5 09NYPIRG says it can take years to hear back from the BOE and, when it does, the message is often that a routine audit of entities was done, any issues were addressed and that the matter has been resolved.

BOE Donation Overages 2006 + 2007 ResponseMahoney notes that a number of corporations listed in their complaints have continued to give higher than allowable contributions throughout the years despite multiple complaints.

Additional information obtained by NYPIRG through other FOIL requests shows that the BOE has not taken action against corporations for any of the violations NYPIRG has pointed out. In fact, the FOILs do not show the actions the BOE claims to have taken by referring cases of major campaign finance scofflaws to the Albany County district attorney.

Speaking of Monserrate and Espada — it has been a while since they last filed, and they had significantly more money on hand than Hawkins. Monserrate’s committee, Monserrate 2010, last filed with the Board in 2010 when they reported having $46,731.51 on hand. Espada for the People reported having $62,593.51 on hand in a 2008 pre-primary filing.

During Espada’s entire sordid term in the Legislature, reporters would routinely call the BOE to see if his committees had filed or paid fines. The answer was almost routinely no, but that negotiations were continuing. Now Espada has been convicted on federal fraud charges for stealing $500,000 from the the publicly- funded health clinic he ran — and there is still no official reporting of where all his campaign cash has gone.

Neither Espada nor Monserrate or representatives of their campaign committees could be reached for comment.

“The fact that the Board does not perform any audits raises the disturbing possibility that some of these candidates have simply pocketed the money,” Mahoney said in a statement. “While the vast majority of these filers may not have engaged in serious violations of the law, the Board’s anemic oversight and enforcement creates the impression that non-compliance with the law carries little risk of real consequences.”

Another legislator who has yet to file an activity report, Assemblyman William Boyland, is facing federal bribery charges on allegations he solicited a $250,000 bribe from two undercover FBI agents. Prosecutors allege that Boyland asked for the cash to pay off legal bills from an earlier bribery indictment that he was acquitted of. (Boyland did not comment when he was arraigned on the latest bribery charges in November; his attorney said they would "defend this case.")

Boyland’s committee, William F. Boyland Jr. Reelection Campaign, last reported having $39,950 on hand in July 2010.

Messages seeking comment were left at Boyland's office and with a representative, but were not returned.

One of the BOE’s many defenses of its enforcement has been that it is understaffed.

“Since the law was changed in 2005, and local filers were required to file with the State Board, our total number of filers has increased more than seven-fold, going from 1,716 in 2004 to more than 12,300 last year,” wrote BOE spokesman John Conklin. “During that time the resources allocated to the Board by the state have not kept pace with that increased workload. The suggestion that we have not asked for additional resources is simply untrue.”

Mahoney says the BOE has done little to publicize their need for more staffing.

And, in 2007, the BOE was given funding to beef up its enforcement staff by Gov. Eliot Spitzer.

Barbara Bartoletti, of the New York State League of Women Voters, recalls working on Spitzer’s transition team and advocating for more enforcement at the BOE. In the end, $1.5 million was allocated in Spitzer’s first budget so that the BOE could hire 11 full-time enforcement staff.

“They just didn’t have the political will to use it. The status quo works for them,” Bartoletti said.

A year later, with Gov. David Paterson in charge and with a gaping hole in the state budget, he swept unused agency funds — including the BOE’s — back into the general fund.

Battling the Boss in Brooklyn

NEW YORK — For the average citizen, trying to run for office can be frustrating and confusing at the least, and downright intimidating and repulsive at the worst.

But if you happen to be running In Brooklyn and have the backing of someone like party boss Vito Lopez, suddenly doors begin to open for you, you have decades of experience on your side — and an entire organization of politicos who know how to navigate the political system and control who gets to run for office.

But over the last few years, a group of insurgent Democrats have come together to try to challenge Lopez and his stranglehold on the party structure that determines who gets to run for office. They want to make getting involved in politics a process that is welcoming by educating and involving as many disgruntled politicos as possible. They have forme an alliance, the Brooklyn Reform Coalition, bringing together some of the borough’s top reform political clubs.

“We would like the party leadership to be more responsive to the desires of the growing progressive wing of Brooklyn's Democratic party,” said Matthew McMorrow, the co-president of Lambda Independent Democrats.

Besides the Lambda Independent Democrats, the coalition includes political reform clubs from all parts of Brooklyn: New Kings Democrats, Independent Neighborhood Democrats, Central Brooklyn Independent Democrats, Bay Ridge Democrats and the Southern Brooklyn Democrats.

Working Together

Alex Low, president of New Kings Democrats, said the clubs worked together on issues such as last year’s fight for marriage equality. He said the groups knew they had similar reform initiatives, though they targeted different neighborhood issues.

But this year, Low said the coalition’s top priority is to change the system itself by recruiting people across Brooklyn to run for county committee so they can level the power of chair Lopez.

Two years ago, NKD was able to recruit over 100 local Brooklynites to run for the unpaid positions; now the coalition has managed to increase the number to 260.

“This year, by using social media, community organizing, and word-of-mouth outreach, the Brooklyn Reform Coalition hopes to increase tenfold the number of reformers elected to the county committee," the coalition said in a statement.

County committee positions give Brooklynites from each election district the opportunity to organize neighborhoods, attend regular meetings and free members to nominate candidates for special and judicial elections.

Hard Reality

Rivaling the power of the party boss in county committee is not that simple, even now that the Brooklyn Reform Coalition’s clubs have banded together.

Low said it will take several years for county committee members of the Brooklyn Reform Coalition to even be able to formally meet. Currently, the party boss can call county committee meetings which according to Low happens just “once every two years.”

The county committee — a less glamorous structure compared to the state’s Assembly and City Council — is made up of 5,000 members.

“The biannual meeting resembles the court of Louis XVI more than an institution of American democracy," wrote former NKD member Nick Juravich in Dissent magazine earlier this year.

Matthew Cowherd, former NKD president and board member commented on the situation saying infiltrating the county committee to rival the party boss will take some time, especially when it comes to nominating candidates for special elections.

“We don’t have the numbers to claim the majority. We don’t even have enough votes to outvote. We’re not there yet ... but having a few people to raise awareness and educate the importance of the seat changes the game,” he said.

Reform Candidate

A notable win against the old Brooklyn Democratic machine came from Lincoln Restler, who put his political reform club on the Lopez radar after reeling in $60,000 for his successful district leader campaign to defeat a Lopez-backed candidate in Williamsburg.

Despite the win, Restler recollected the initial struggles he had encountered in his first race for district leader. “I was surprised by how few people were willing to stick their neck out and stand up in support of my first, our first campaign, to try and shake up the old democratic machine in North Brooklyn,” he told the Gazette.

Restler’s route to politics is unlike many of his political counterparts. Before his interest in reforming Brooklyn politics, he considered a career in academia with a focus on the Caribbean. In 2010, he co-authored a study on financial literacy among Dominicans in New York City for the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute.

Restler's group, NKD, was created in 2008 by a group of twenty to thirty year olds who wanted to use their momentum from the Obama campaign to get local people involved in local politics. The more people get involved, the fewer of Lopez's organizations candidates are gifted seats.

Getting all kinds of people involved in progressive Democratic politics from all walks of life is a goal of the organization.

Restler said his experiences working with local people to build community gardens and organize against subway cuts were examples of the open and inclusive process needed in politics today.

“These are substantive examples of Brooklynites taking ownership of the issues they care about in their community,” he said.

While it is also an unpaid position, being a district leader does carry some weight: they select poll workers, select civil court judge nominees and elect county chairs.

A Movement

A recent press conference showcased the growing support Restler and his movement enjoys as it was attended by many politicians including Congressman Jerry Nadler, Congresswoman Nydia Velazquez, Brooklyn Senators Eric Adams, Daniel Squadron and Velmanette Montgomery, Assembly Members Joan Millman and Jim Brennan, and Council Members Diana Reyna and Brad Lander.

“Everyone that I talk to is intrigued by the prospect of dismantling the old Brooklyn machine and replacing it with a new Brooklyn Democratic party that is reflective of our values,” Restler said.

Restler said Jesus Gonzalez, who made a failed bid for the Assembly in 2011, is also a good friend of his. Restler said Gonzalez has the ability to connect with northeastern Brooklyn in “very deep and real ways."

Last year, in Bushwick’s state Assembly special election, Lopez backed Rafeal Espinal, who defeated the young community organizer Gonzalez in an impossibly close race.

“His commitment to social justice, long time dedication to police accountability, and his talent for youth organizing are exactly the skill set I would hope for in an elected official,” Restler said.

Bill Samuels, head of the New Roosevelt Initiative, said he was impressed with young reformers like Williamsburg’s Restler running for district leader and Bushwick’s Gonzalez now running for City Council.

He said young people should find other ways to get involved with the community if they want to be a political leader.

“In the long run people should want to go to law school, be a reporter, or a community organizer so they don’t have to beg some boss,” he said.

The Boss

The Brooklyn Kings County Democratic Chair or “party boss” Vito J. Lopez is currently serving his 14th term in the Assembly, having held office since 1984. While Lopez is a legislator with a load of seniority, his power base is in Brooklyn, not Albany where he has served as the chairman of the Kings County Democratic Party.

Lopez built “the prototype of a modern inner-city political machine,” according to a NYT archive on the Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Citizens Council. Lopez founded the nonprofit, which faced a series of federal investigations despite it receiving over 870,000 in discretionary funds from the City Council this year.

Lopez undoubtedly holds power over Brooklyn voters who often vote for the Democratic party dominated by his candidate endorsements making it difficult for a non-machine or independent candidate to run.

Lopez did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

A fact often recited by Brooklyn political reform clubs is that three out of the last four Brooklyn party bosses were indicted for corruption and that Lopez is under investigation.

Restler says that fighting perceived corruption in Brooklyn politics is one of his greatest motivations.

“The stranglehold of the old machine on our county’s political process has had a tighter grip here in Brooklyn than any other county in the city and that is what needs to be broken,” he said.

But Flora Davidson, a professor of urban studies and political science at Barnard College, said political machines are slowly losing their grip.

“Any candidate who can mobilize support can challenge existing leadership by raising money and generating sufficient voter turnout,” she said.

Campaign Finance Reform: What's Needed Besides Public Financing?

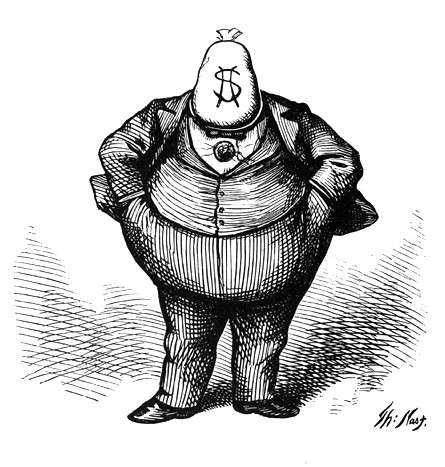

Cartoonist Thomas Nast's classic portrayal of the "fat cat" politician.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s pledge of campaign finance reform has widespread support from New Yorkers fed up with a system in which wealthy individuals, businesses and unions overwhelmingly underwrite the cost of running for state office, thereby endearing themselves to lawmakers.

Much of the discussion over campaign finance reform has revolved around the issue of public financing. A public financing system similar to the one in New York City would encourage average New Yorkers to play a role in funding campaigns, since their donations would be magnified through a public match.

It is important to note that public financing is only one part of New York City’s exemplary system. While their laws and regulations are better than the state’s in a variety of ways, two of them — lower limits and a functioning administrative body — are essential parts of any bill hoping to replicate the City’s success.

Most of the state legislative proposals would significantly lower contribution limits for participating candidates by bringing them close to the more reasonable federal levels.

These lower limits, however, need to apply whether or not candidates choose to participate in a public financing system. If statewide candidates can continue to receive donations of up to $60,800 per donor, will there be any incentive to opt in to the public finance system?

Even these astronomical limits can be easily avoided. Limited Liability Companies are bizarrely exempted from the regular corporate donation cap and treated as individuals. Further, businesses with separately incorporated divisions may give the maximum amount through each division.

Developer Leonard Litwin exploited both of these loopholes to give nearly a million dollars in the past six months, and so far this election cycle has given the governor more than four times the limit usually placed on individuals.

Political parties can receive $102,300 per year from each donor.

However, the five largest parties in the state all have “housekeeping committee” accounts that can receive unlimited donations, even from those who maxed out on this six-figure limit.

While use of this money is ostensibly limited to non-electoral purposes, it goes toward expenditures that few logical individuals would believe exist outside the realm of campaigning, such as the hiring of campaign staffers, paying rent on campaign offices, and running push-polls on behalf of candidates campaigning for office.

New York’s Republican Party has recently proved how fungible this money can be by doing the functional equivalent of laundering housekeeping funds through two different committees and transmuting it into hard money.

Lowering limits on party fundraising is just as important as doing so for candidates: even those candidates who participate in a public financing system could solicit huge checks on behalf of parties with the tacit understanding that this money would eventually be transferred their way or spent on their race.

It’s also clear that administration and enforcement of the campaign finance laws need to taken out of the hands of the Board of Elections, an agency designed to be partisan. The state Board is incapable of taking any action that goes against the will of members in good standing of either of the major parties.

An example is that each year hundreds of donors give more money than they are allowed by our incredibly lax contribution limits.

Yet the state Board never investigates these most basic violations of the current law — even when NYPIRG has, on several occasions, attempted to help them by providing lists of donors who have crossed the legal threshold. The Board has never taken action against any of these individuals or businesses, many of whom are annual violators.

The state Board is also an anemic administrator. Some recent evidence can be found in the Board’s bungling of a statutory requirement to create rules for the disclosure of independent expenditures, such as those made by Super PACs, by January 1st of this year. Its draft proposal was nearly two months late and failed to capture the spending this law sought to expose. As of the beginning of August it was still not finalized.

With the Board’s history of failure in administering our current weak laws, there’s simply no reason to believe they would be capable of overseeing a new, $50 million per year public financing system.

There are other reforms that NYPIRG and other watchdog groups believe should be part of a campaign finance package, including requiring better disclosure, such as the names of donors’ employers and the identification of “bundlers,” and a lowering of limits for candidates in some of the larger localities in the state.

There will also be several areas in a potential bill that could create loopholes, including letting incumbents carry over their huge war chests into future elections.

These details can be worked out when serious talks about passing a bill commence.

A vigorous public financing system could help New York become an exemplar of participatory democracy.

However, New Yorkers shouldn’t be asked to pay for a public campaign finance system that doesn’t really promise to dramatically reduce the influence of special interests in political campaigns.

We have to get it right, since whatever program is created is likely the one we’ll live with for the foreseeable future: legislators won’t rush to work out the glitches in a system that helps perpetuate their 98% reelection rate.

New Yorkers should echo the governor’s call for overhauling the state’s shameful campaign finance system by exerting pressure on legislators to pass truly comprehensive campaign finance reform.

They should be mindful, however, that any proposals include the reforms needed to make a public financing system successful.

_____

Bill Mahoney is the legislative operations and research coordinator for New York Public Interest Research Group

How the State's Elected Elite Stays in Power

Longtime state Sen. Velmanette Montgomery seen at the first interactive ethics reform forum in Albany on May 4, 2011.

NEW YORK — In an alternate reality, New York is gearing up for the most competitive elections it has seen in years.

District lines have been redrawn to represent voters across the state. Campaign financing has been overhauled to reduce the amount corporations and individuals can give to candidates, while loopholes that allow businesses to skirt limits have been plugged. Good government groups have nothing to do.

But that is not the reality we live in.

Instead, in the real New York, fair redistricting has been put off for another decade, leaving the same old incumbents clinging to their power in the state Legislature. Campaign finance is being largely ignored, though good government groups are spending time this summer trying to rally support to change how elections are financed.

This is, after all, a state with one of the highest incumbent reelection rates in the country.

Not that voters are happy with the representation they get from their state lawmakers. An October 2011 Quinnipiac poll found that 63 percent of New York voters disapprove of the way the members of the state Legislature are handling their responsibilities.

So what is it that keeps state legislators in power? We take stock of the top reasons to get you prepared for this year's election.

Complacency and Familiarity

The simplest explanation for New York’s high incumbency rates, according to Barbara Barr of the League of Women Voters of New York, is complacency and familiarity.

“People will vote for the people they know,” Barr said. “It's very hard for people to break in.”

And once they are in office, elected officials have taxpayer-paid tools at their disposal to keep their name in the public.

For instance, office holders have tools at their disposal that allow them to use taxpayer money to communicate with constituents: They can send out informational newsletters with their names on them until shortly before an election and hold community events.

“There are so many different ways in which incumbents manage to get their names out to the public,” said Susan Lerner, executive director of the advocacy group Common Cause New York. “Incumbents are able to use the power of their office.”

Because of these reasons, this year’s incumbents will be reelected, Barr predicted, “unless they don't want to be or unless something really strange happens.”

The legislators themselves are well aware of these advantages.

“The fact that you can send newsletters, yeah I guess that could be a perk,” said Jim Vogel, spokesman for state Sen. Velmanette Montgomery, who has been in office representing parts of Brooklyn since 1984.

However, Vogel explained that Montgomery uses the newsletter as a necessary means of communication with her electorate, not as a campaign tool.

“She really lets people know what she’s doing,” he said. “The senator has always done a really good job of being there for her people.”

It's Hard to Run For Office

Another impediment to real competition in legislative races is the complex system of petitioning to get on the ballot, according to Lerner.

“If you are a challenger, the petitioning process is very, very onerous," she said.

Often, primary challengers don’t even get a shot at office, with candidates being picked solely by their party officials during a special election.

The parties also run candidates when you aren’t looking.

According to the Citizens Union report of the 212 legislators who took office last January, 26 percent were first elected in a special election, for which the average voter turnout was 12 percent from April 2007 to the report’s writing.

These representatives — whose initial election is barely influenced by the people they represent — are then reelected, with all the advantages of other incumbents.

“That is done to ensure that their replacement is… picked by the structure of the political party, not by the voters,” Lerner said.

Remember Redistricting? Who can forget?

Another way to ensure incumbents’ victory is through the redistricting process.

This year, new districts have been proposed, voted on and signed by Cuomo, but official maps have yet to be released.

CUNY’s Center for Urban Research has a useful guide to the legislature-approved lines, and the state Board of Elections points voters to the legislative task force’s website for maps.

When asked if the redistricting process was going well, BOE spokesman John Conklin said: “I'm not sure if I can characterize it as such.”

Part of the problem with redistricting is that although it is intended to adapt districts to new census data, the process is often used to custom-tailor districts for incumbents.

“Incumbents from the majority parties tend to have their districts drawn to have voters who are more favorable to them in the district,” said Bill Mahoney, research coordinator at the New York Public Interest Research Group.

Because new district lines are drawn by a panel of legislators, a majority of whom come from the party in power, the changes often contribute to the cycle of incumbency.

“If we had an independent and non-partisan redistricting process here, we would have more races that are competitive,” Lerner said.

Partisan redistricting can lead to what Mahoney called “some of the wackiest districts.” One example, cited by Lerner, is Marty Golden’s senate district in Brooklyn, which she described as having a “really, truly bizarre shape.”

She said it appeared to have been drawn "to find as many Republicans to elect a Republican incumbent."

Golden could not be reached for comment.

Is Incumbency Bad?

While good government groups criticize the high rate of incumbency in New York, others say being re-elected repeatedly can give politicians the skills and influence to meet their constituents' demands.

“Being an incumbent just means that [voters] know… that their concerns are going to be addressed by this woman,” said Montgomery's spokeswoman.

And while he acknowledged some incumbents abuse their position, Vogel said that was not the case across the board.

“We all know there have been folks who somehow have been around forever and they don't even communicate with their constituency,” Vogel said.

This year, Montgomery is running in district 25 as opposed to 18 as in previous years due to redistricting. However, the size and shape of her districts are virtually indistinguishable. Her re-election is, in fact, inevitable, says Vogel, because no one is running against her.

“It's kind of a moot point,” he said.