City Council Incumbent Gets Respect Championing Stuyvesant Town

NEW YORK — At a recent forum of mayoral candidates at Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, one politician emerged as a clear winner: City Councilman Dan Garodnick.

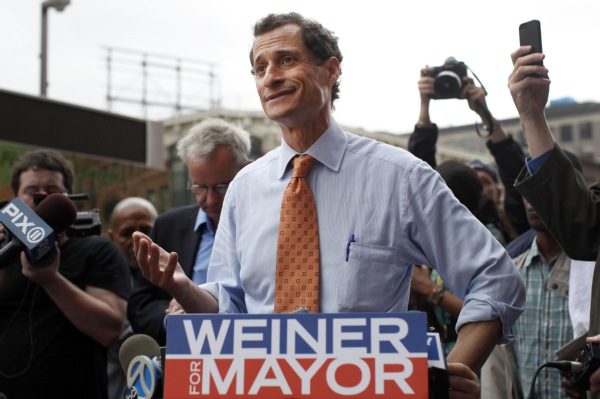

One candidate after another stepped up to the lectern, thanked the audience for being there and paid tribute to the councilman, who sat at a small table at the side of the stage. Democrat Anthony Weiner prefaced his remarks by telling the crowd he felt obligated to “suck up” to Garodnick.

The accolades had much to do with venue. State records show that the Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village is home to nearly 15,000 registered voters — almost 10,000 of them registered Democrats. That translates into quite a voting bloc.

The mayoral hopefuls were keenly aware that Garodnick, who grew up in the sprawling complex and lives there in a 10th floor apartment with his wife and toddler son, had championed tenants’ interests during a tumultuous period. Since he was first elected to the City Council in 2005, the complex underwent a contentious sale, a class action lawsuit and a devastating hurricane. How Garodnick responded to those challenges has helped shore up his political profile.

“Yes, he’s riding a crest of popularity because he’s always been there for us in times of crisis,” said tenants association chair Susan Steinberg. “There are a great many people here who support him and take an active part in his campaign.”

The two-term councilman has parlayed his popularity into his all-but-certain re-election and possibly a stint as the next speaker of the City Council.

“I have a Republican or Libertarian opponent,” said Garodnick when asked about his 4th district campaign. “I don’t know who it is. I know there’s a name out there.”

The name is Helene Jnane, an attorney who has the endorsement of the Libertarian Party. She hasn’t raised any money for a campaign, but said she plans to launch a website soon.

Jnane rejected the notion that Garodnick is politically invincible and was quick to note that his vote on two bills to reform the city’s stop-and-frisk policy have cost him support. The Patrolman’s Benevolent Association denounced Garodnick’s vote in fliers it mailed to district residents, for instance.

“I want to campaign on principles, sound government and accountability,” Jnane said.

She’s challenging a savvy politician who became the darling of STPCV and a crusader for affordable housing soon after joining the Council. During his first year in office, the 41-year-old Democrat supported the tenants association’s attempt to purchase the 80-acre complex, the largest enclave of middle-class renters in the city. The following year, he introduced a bill creating the Tenant Protection Act, which essentially bars property owners from harassing low-rent tenants out of their apartments to make room to market-rate renters.

“It’s not every day that you’re elected to the City Council and six months later a quarter of your district goes up for sale,” he said.

The highly leveraged purchase of STPCV by Tishman Speyer for $5.4 billion all but crushed the hopes of residents who wanted control of their community. When the new owners defaulted on their debt in 2010 and handed the property over to the bondholders, tenants worried. When their landlord challenged about 870 rent-stabilized leases, tenants became infuriated.

Garodnick called for a moratorium on the lease challenges and set up a “tenant hotline” and legal clinics for residents.

“Dan took a leadership role in helping residents weather the Tishman Speyer sale and what followed,” said Darren Marks, president of the Lexington Democratic Club. “People there are politically savvy. And I think they’re thrilled with Dan.”

Tenants filed a class action lawsuit claiming Tishman Speyer and Met Life, the previous owner of the complex, had illegally converted rent-stabilized apartments into market-rate units. A settlement in the case promised to reimburse tenants for more than $68 million in over-paid rents. But it also stipulated rents could be raised for some tenants who were paying less than what the property owners could legally charge.

When more than 1,000 residents were subsequently slapped with mid-lease rent increases in May — a few as high as $900 a month — Garodnick publicly rebuked CW Capital, the company managing the complex.

“That was not about the settlement,” he recalled. “That was about CW Capital taking a step that was crass and unnecessary and which really impacted the lives of many residents. Some people had to move.”

Newer residents complained that CW Capital’s rental agents had told them not to worry about any rent hikes.

“That’s why we brought the issue to the New York state attorney general,” Garodnick said. “And that’s why he investigated and forced them to roll back the increases for those people who had a misrepresentation by a leasing agent.“

Garodnick also spearheaded efforts to help residents in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. He organized door-to-door checks on elderly residents and evacuated those who wanted to leave but couldn’t navigate the darkened hallways and stairwells. His office collected donations of food, water and other supplies and opened a volunteer center in Stuyvesant Town. He later chastised CW Capital for failing to keep tenants informed about building repairs.

“He’s the hometown hero there,” said Mark Thompson, a government relations advisor for Capalino and Company and a longtime Stuyvesant Town resident.

Thompson considered running for the 4th district seat when Garodnick announced his intent to seek the city comptroller position. Garodnick pulled out of that race when fellow Democrat Manhattan Borough President Scot Stringer opened a campaign for the comptroller job.

“I support Dan one-hundred, no, one-thousand percent,” Thompson said. “Nobody was going to oppose him and I feel there’s a lot of support for Dan to be the next Speaker.”

Not that Garodnick’s popularity at the complex is all that matters. A candidate can win the 4th district seat without carrying STPCV because the bulk of the voters reside on the Upper East Side, said Dara Adams, a lobbyist who shut down her campaign for Garodnick’s seat when he decided to seek reelection.

“But it’s a very important voting bloc,” she said of STPVC. “From a political perspective, it’s home to a lot of Democrats with shared experiences.”

It’s also an efficient campaign stop for any politician. A candidate could attend a tenants association meeting and encounter a thousand potential voters.

“The residents there are civic-minded and the place has a reputation for high voter turnout,” said state Assemblyman Dan Kavanagh, whose district includes all of STPCV. “In politics, it’s often easier to communicate effectively with people who have something in common and organize themselves — even more so when the community is under siege by powerful economic forces.”

Garodnick still supports a purchase of STPVC by its tenants. And the association is assembling an offer for the property in partnership with Brookfield Asset Management Inc. But CW Capital has been unwilling to talk about selling.

Still, it’s likely that STPCV will continue to draw Garodnick into the media spotlight.

“In reality I am focused on a variety of different issues from greening the city to consumer protections to improving our transportation options and streetscape throughout the district,” he said. “But there is no question that I am deeply in tuned to the concerns of the people in Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village because of the incredible upheaval we have seen in the community.”

Garodnick’s reelection campaign can tap into a stockpile of nearly $700,000 in contributions, most of it raised during his abbreviated candidacy for comptroller. With no serious contender in sight, it’s unlikely he’ll need to.

As for taking the reins as the next City Council speaker?

“At the moment all I’m focused on is my reelection and asking my constituents for an opportunity to serve the district again,” he said.

Wham! Bam! Pow! Slugging It Out In The Queens Borough President Race

NEW YORK — Peter Vallone Jr. was ripping open his suit, a red “V” blazing off his blue chest. Promising to reduce crime as both a superhero and a Queens councilman, Vallone charged through a cityscape, an American flag clasped in his right hand.

His rival was not amused by the ad. “Peter Vallone drew a comic book,” Melinda Katz’s campaign said in a statement. “That pretty much tells voters all they need to know.”

Vallone’s colorful mailing for his Queens borough president bid, blasted out in early August, perfectly illustrated the contrasts between himself and Katz, the other top contender for the open seat. Where Vallone is a bombastic defender of the New York Police Department and their controversial stop-and-frisk policy, Katz is a more understated critic.

Vallone, a term-limited councilman, and Katz, his former colleague in the City Council and a well-heeled attorney, have made the Democratic primary for the somewhat ceremonial yet potentially influential post a two-person slugfest. While the most sparks have flown between Vallone and state Sen. Tony Avella, also a former Council colleague, fundraising numbers tell a story of a race that will come down to whether Vallone’s outsized personality and superior name recognition can defeat Katz’s army of endorsements and airtight coalitions.

The candidates are expected to attend a debate on Tuesday night sponsored by Citizens Union, the sister organization of Gotham Gazette.

Regardless of who wins the race, the next borough president is likely to be a departure from the understated 12-year reign of Helen Marshall.

“I think there was definitely a sentiment among the political establishment that Queens wasn’t getting a fair share,” a Queens political insider said, referring to Marshall. “A strong borough president carries a lot of clout. You don’t necessarily have a lot of power in institutions but you have power through word of mouth.”

Since a charter revision more than two decades ago that ended the Board of Estimate, the borough president position has been relatively powerless. Borough presidents can draft legislation and allocate a limited number of funds to various programs, but pale in comparison to the mayor or even comptroller in terms of shaping city policy. Unlike members of the City Council, the borough president has only an advisory vote on any projects or legislation. There are some smaller perks, like appointing members of community boards.

Still, as the boisterous Marty Markowitz demonstrated in Brooklyn, a borough president can be an effective cheerleader for the borough. While Markowitz has been derided for his clownishness, he has labored to make Brooklyn a brand-name across the country while also wielding the political clout he accumulated from decades as a state senator to boost controversial developments like Atlantic Yards behind (and in front of) the scenes. As the term-limited Markowitz reluctantly exits the scene just a few miles away, the candidates for Queens borough president are hoping they can leave the same sort of imprint on their own borough.

Queens, like Brooklyn, is an incredibly diverse locale, home to a booming Asian and Latino population, a rising tech sector in Long Island City, its own hipster haven (Astoria), its own contentious and ambitious development (Willets Point) and its own sprawling, iconic park (Flushing Meadows Corona Park).

The motorcycle-riding Vallone, positioning himself as a more politically conservative version of Markowitz, is quick to point out why he, and no else, would be the best steward of all that Queens has to offer.

“I’ve spent my entire tenure in government fighting for small businesses and fighting against higher fines and more regulations and over aggressive enforcements against small business,” he added. “And the second thing I bring, which my opponents don’t, is a background in keeping people safe. I was a prosecutor for six years and for the last 12 years I’ve been public safety chair, working closely with [Police Commissioner] Ray Kelly to bring crime down 35 percent since 2002.”

As if to emphasize that, in his comic book campaign ad Vallone is not only depicted as a crime-fighting vigilante; it also pointed out that Kelly, still popular in parts of Queens, once said, “we are safer” because Vallone chairs the City Council’s public safety committee. “Peter Vallone is to graffiti what Rudy Giuliani was to squeegee men,” the mailing reads.

Vallone is no doubt the flashiest candidate in the race. Quick-witted and media-savvy, Vallone has led an angry and so-far fruitless crusade against the decision to rename the Queensboro Bridge after former Mayor Ed Koch. Vallone’s beef is not with Koch, but simply with the idea that a bridge solely named for Queens now shares its name with a non-Queens figure. When Markowitz half-jokingly suggested that a proposed soccer stadium for Flushing Meadows Corona Park should come to Brooklyn instead of Queens, Vallone cut loose, quipping to the New York Post that Queens should probably “lock up the Unisphere” so it wouldn’t be “stolen.”

The son of former City Council Speaker Peter Vallone Sr., Vallone hails from Astoria and once worked in his father’s law firm. Though his father is now a powerful lobbyist, Vallone portrays himself as a candidate who will stand up for small businesses across the borough.

Vallone has about $1.2 million left in his campaign account after receiving matching funds. Though a small business champion, Vallone is buoyed by donations from larger real estate companies and construction companies and some big names, including the executive chairman of Barnes & Noble and Eliot Spitzer, then the attorney general.

Katz, backed by the Queens Democratic Party and a host of labor unions and elected officials, has a little over $882,000 left after receiving matching funds. Katz also drew on her extensive real estate and developer connections to raise funds.

A former councilwoman and assemblywoman from Forest Hills, Katz ran and lost two

high-profile races, including for Congress in 1998 to current mayoral candidate Anthony Weiner. A political protégé of former Comptroller Alan Hevesi — who recently finished serving a prison sentence on corruption charges — Katz has staked out more liberal positions than Vallone, including supporting the Community Safety Act, a package of bills that would, among other things, create an inspector general for the NYPD, which Vallone angrily opposes.

Once the chair of the powerful Land Use committee in the City Council and a veteran of long-time Borough President Claire Shulman’s office, Katz promises a more activist, policy-heavy borough presidency, proposing to re-introduce Shulman’s education “war room” (a close monitoring of school construction and classroom overcrowding in Queens) and unveiling a thorough plan to help restore the Rockaways after Hurricane Sandy.

“I think the differences between candidates are experiences,” Katz said. “As chair of the Land Use Committee, it was my job to bring people into a room, coordinate the communities, the community board, developers, houses, the city agencies and get things done. And for 20 years I’ve taken on that role for many different fights.”

Katz was able to secure the crucial Democratic Party nomination over another party stalwart, Councilman Leroy Comrie, who has since left the race. This has granted Katz at least one advantage over Vallone: Prominent endorsements from individuals like the Rev. Floyd Flake in the predominately black community of southeast Queens, which Comrie represents — making Katz a white candidate with inroads into communities of color.

Everly Brown, a little-known real estate developer, is the non-white candidate in the race, meaning Katz, Vallone and Avella will need to pull blacks, Latinos, Asians and even Orthodox Jews into their winning coalitions.

With her broad range of endorsements, Katz stands the best chance of doing this.

But despite their front-running statuses, both Vallone and Katz were unwilling, in interviews, to criticize one another. Vallone even called Katz “a friend,” but the same can’t be said for his relationship to Avella, a long-time northeast Queens representative who has warred with Vallone repeatedly on the campaign trail.

At a debate in June, Avella accused Vallone of checking his phone for answers to certain questions. Vallone vehemently denied the charge, claiming he was simply texting his daughter. A rival vouched for Vallone.

But the most pointed language came when the Vallone campaign unsuccessfully challenged Avella’s petitions for getting on the ballot. Avella ripped into Vallone, accusing him of trying to force him, by any means necessary, from the ballot.

“Personally, I think he’s a bully and a coward and afraid of having me on the ballot,” Avella said in July.

Both Avella and Vallone are known in Queens for their outspokenness and relative independence from the party infrastructure. Both are even competing for a similar subset of voters: white, moderate home-owners, living in places like Bayside and Douglaston that Avella represents. Vallone’s brother Paul is running for the City Council seat that Avella represented for eight years.

“His campaign has been typical Tony Avella,” Vallone said. “It’s replete with press stunts … I think that the people he represents sense he’s an absolute hypocrite.”

Avella, however, sees himself as the outsider in a race of well-heeled establishment candidates fundraising excessively from wealthy donors.

“I think one of the things I’ve been saying at a lot of meetings I’ve been going to is that it all comes down to trust,” said Avella, who prides himself on battling real estate developers to maintain the “character” of the bucolic, single-family home neighborhoods he represents. “Let’s look at a couple of key votes in the City Council. One of the things I talk about is the term limits vote. I ask, ‘how do you feel about the mayor and 29 members of City Council overturning term limits?’”

“There’s this frustration,” Avella added, referring to the 2008 vote to temporarily overturn the term limits law. “Well I want you to know, Vallone voted with the mayor and Katz voted with the mayor to extend term limits.”

Even more the outsider than Avella, Brown, who has managed to only raise only $1,701, said he is running on a platform of easing access to the ballot and absolute transparency, even posting his personal cell phone number on his campaign website. Brown has run for office before, never successfully.

“You know, the media tries to stifle me a lot,” Brown said, complaining also that the Katz campaign had challenged his petitions. “It was a long hard fight, they tried to get rid of me, but I’m still here, fighting.”

Policy Dreamin' At Manhattan BP Candidate Debate

NEW YORK — It is a familiar refrain by now: in a field stacked with Democratic candidates, it's still too difficult to draw policy lines among the candidates for Manhattan borough president.

That's even harder to do when you have two candidates who have served three terms on City Council, another finishing her second and a fourth who has never held elected office. Case in point: At a debate last night, all four candidates seemed to agree on almost everything — even listing the same priorities in the exact same order.

All of them think Mayor Michael Bloomberg's Midtown East rezoning plan is moving much too fast. All of them concede they are willing to revisit the City Charter to improve land use procedures. They all want to diversify their appointments. And they want to connect the limited powers of the office they are seeking to a wider breadth of pressing issues.

Washington Heights Councilman Robert Jackson and Upper East Side Councilwoman Jessica Lappin said that they would focus on housing affordability, supporting public education and incentivizing job creation. Upper West Side Councilwoman Gale Brewer, meanwhile, listed affordability, jobs, library and school funding before adding a fourth priority: quality of life.

Only the one downtowner focused her message on one of the few powers that borough presidents still wield. Former Community Board 1 chairwoman Julie Menin, who is probably best known for leading the fight to keep the Sept. 11 terror trials out of Lower Manhattan, called for a comprehensive development plan, proactive community boards and participatory budgeting.

"We have to, in my opinion, completely change the direction we're going in terms of our land use system," said Julie Menin at the forum hosted by Gotham Gazette sister organization Citizens Union and NYC Community Media. "It's the primary reason why I'm running, and I have a very clear vision on how to change it."

Menin, previously a board member of Citizens Union, spent the evening asking for a master development plan for the borough, and argued that many of the city' ills — unaffordable housing, overcrowded classrooms and poor quality of life — could be traced to how the city willfully approves large scale developments "without a nexus to what it's doing to our communities."

But no one was asked about or brought up two of the borough’s most difficult land use items: their positions on the recent 10-year permit limit on Madison Square Garden and the 91st Street marine transfer station. After all, zonings are one of the few things that borough president can actually weigh in on since the City Charter was revised in 1990.

Since then, borough presidents have been effectively limited to offering input on development plans, capital pending and various appointment powers, including to the city’s many community boards.

Menin was also the only candidate to reject the idea of City Council discretionary funds as a means to fund capital projects, instead opting for a participatory budgeting system. The three other candidates said that they too would consider expanding participatory budgeting, but celebrated the money that they've been able to direct to local projects as Council members.

Lappin, ending her second term on the legislative body, was the only one to praise the sitting and outgoing borough president, Scott Stringer — not once, but three times. She said she would incorporate and expand some of Stringer's plans, including his Manhattan Community Grants Program panels that she said she has sat in on. The one change she'd make, ironically, is eliminate elected politicians from participating in the panels.

Otherwise, Lappin said she too was concerned about reforming the city' land use process, but sees the expansion of community based planning as the answer.

"One of the ways that I would tackle all of these issues is by using the mechanism that exist," she said. "The 197a process to make sure that communities are doing bottom-up — not top-down — bottom-up planning looking at affordability. Looking at school seats, senior services, homeless shelters, day care centers. And making sure that we're planning not just one, two years out, but 10, 15 years down the road."

Lappin took painstaking steps to position herself as the education candidate, often reminding the audience of her own public education roots and experiences as a parent of public schools children. But she wasn't the only one to do so. Previously serving as a community school board president, Jackson said that he's carried his focus on education into his career on the Council.

"When the mayor said he was going to lay off 6,000 teachers, I signed a pledge — along with Gail and Jessica — to say we would not vote on a city budget unless the money was restored back to education," Jackson said, adding that he spoke up again in the Council and bucked City Council Speaker Christine Quinn to get action on school funding.

But while Jackson has been able to help lead discussions on some of the issues most important to his constituency, his legislative record pales in contrast to some in the race. By no means the least productive member in the Council, Jackson's three terms translated to 11 enacted laws, almost half of which were passed in 2004, and dealt with contracts and bid procedures.

By comparison, the other three-term Council member in the race made sure to tout her legislative record on some of the biggest laws over recent years. Brewer called upon her landmark bill to open up city agency data troves for public use, as well as three years of advocacy for her paid sick leave law, despite years of resistance from the city's business community, the Bloomberg administration and fellow Council members.

Often a foe of major development plans, especially those that put small businesses and historic sites at risk, Brewer was the first among the candidates to speak out against the Midtown East rezoning process. She listed a series of question still unanswered: the affordability of housing proposed in the new plan; infrastructure and transit challenges; and air rights over the neighborhood.

"I could go through 10 more questions," Brewer said. "With any proposal there are some good ideas but they always need a lot of time. Hudson Yards on the West Side was five or six years in terms of planning. That's the kind of planning you need in order to do a proposal correctly."

While the candidates seemed to agree on many of the issues discussed, there were some small moments of contention. The candidates were allowed to ask each other questions, which, even when asked respectfully and politely, elicited reactions from the crowd.

Menin began by asking Jackson about his vote in support of giving Mayor Michael Bloomberg a third term, which also gave Jackson himself a term limit extension beyond the usual two terms. Jackson in turn said that he was never in favor of term limits.

"If you go back and look at the record on the initial vote for term limits in Manhattan, the majority of the people said no to term limits," he said. "The other four boroughs, the majority said yes. So Manhattanites, those that voted, said no. I didn't cut the deal — the people of New York voted. One point five million voted out of four million plus. Those people that did not vote gave Mayor Bloomberg another term. Not me."

Lappin proceeded to asked Menin why she switched political parties three times within 17 months in 2002, including why she turned Republican during former President George W. Bush's first term.

"After 9/11 we were going through a devastating time," Menin said as some in the audience murmured, explaining that she switched parties at a time when she was trying to represent her community's needs. "I'm very proud that I've been a progressive my whole life; I've been a registered Democrat for over 25 years of my life."

At the end of the day, many of these candidates will still need to convince voters that their vision for the city isn’t trumped by the actual limited scope of influence that borough presidents have on local policy. To that end, the candidates were each asked if they would support the idea of a charter revision, especially to revisit the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure that all borough presidents play a vital role in.

Menin, Lappin and Brewer all suggested that they would be willing to engage in discussions and to pursue charter reform. Only Jackson qualified his response. The councilman supports pursuing revisions that communities are behind but said that, ultimately, the mayor controls the City Charter and can unilaterally knock down any proposed changes.

“The bottom line is that this is what we have and you have to follow the law,” Jackson said. “And within a certain period of time, you must act. If you fail to act, then the recommendations of the City Planning Commission goes forward. People are not going to sit still and wait for a comprehensive plan; people are going to act.”

John Liu Defiant After City Board Denies Funds For His Mayoral Campaign

NEW YORK — Even after losing out on millions in public funding for his mayoral campaign, Democratic candidate John Liu is refusing to back out of the race for City Hall.

"For the last couple of years, I've taken body blow after body blow after body blow. But there’s not going to be a knock down here,” Liu said yesterday following the decision by the city’s Campaign Finance Board to deny his campaign matching public funds.

But he admitted that yesterday's decision by the city’s Campaign Finance Board to deny his campaign matching public funds, after citing irregularities, would take a toll.

"There's no question that this weakens my campaign," he said, as 60 or so supporters stood with him in front of the Municipal Building across from City Hall.

The decision by the board was not entirely surprising given that two of the candidate’s campaign aides were convicted in an illegal fundraising scheme earlier this year. Those convictions failed to dispel questions about the collection of donations by Liu’s campaign. Liu has not been charged or accused in the cases.

Without the public funds and barring any money he can raise between now and the Sept. 10 primary, records indicated Liu had little more than $1.5 million left to spend — leaving him at a considerable financial disadvantage in the jam-packed race for the Democratic nomination.

Liu, who is the city’s comptroller, said that his campaign would strongly consider appealing the board's verdict, but couldn't count on it being successful. Liu and his campaign attorney, Martin Connor, said that even with a successful appeal, it would only give them five or six days to spend the more than $3 million he would have received if not for the board's decision.

"We've got five weeks to work really hard," Liu said. "And though we may not have the millions of dollars that the Campaign Finance Board has chosen to withhold from our campaign and from our donors, the strength of this campaign has never been in the money. The strength of this campaign has always been in the people."

Liu, who stood alongside leaders from CWA Local 1180, DC 37 and the Correction Officers' Benevolent Association, was often drowned out by his supporters, who alternated chants of "Mayor Liu" and "Tell us why."

Despite trailing in many of the polls of Democratic mayoral candidates, those alongside Liu were just as eager to answer reporters questions to Liu.

Without any cue or hesitation, Corrections Officers Benevolent Association President Norman Seabrook spoke up for Liu while resting his hand on candidate's shoulder.

Seabrook tried to make the case that the board's political appointments — especially the two made by and Liu mayoral rival and City Council Speaker Christine Quinn — should have recused themselves from the vote.

When a reporter asked Seabrook who he was, the union leader pointed to the cheering and chanting crowd.

"John Liu," he responded. "We're all John Liu today."

Seabrook pressed for responses from Liu’s other rivals too. Only one has publicly acknowledged the hearing: Former Comptroller Bill Thompson told Capital New York that Liu’s candidacy was a question better suited for the voter than for the board.

"You hate to see something happen that way, and you really would much prefer to see the voters decide," Thompson told Capital New York.

But even if the two board members had recused themselves, the vote to deny Liu's matching funds was unanimous. Board Executive Director Amy Loprest told reporters that the decision was based both on the federal cases against the former Liu campaign as well as an independent investigation paid for by the CFB.

That investigation, the board said, uncovered a pattern of behavior similar to the federal cases.

The board's chair, the Rev. Joseph Parkes, said the potential violations were "serious and pervasive," and put the blame squarely on Liu.

"The candidate is ultimately responsible for the campaign’s compliance with the law," said Parkes' statement, citing the 1988 Campaign Finance Act. "The choice to withhold payment does not require a finding that the candidate has personally engaged in misconduct, however. Under the act and board rules, the actions of a campaign’s treasurer or other agents are legally indistinguishable from the campaign."

To that end, board members argued, their conclusion isn’t a slight to the donors whose funds would not be matched. The responsibility to donors to follow the law, Loprest said, isn’t on the board but rather on the campaign.

During yesterday’s public meeting, Connor admitted that the Liu campaign had suffered it’s shares of setbacks, but that the greater number of Liu's 6,259 individual contributions should still be eligible for matching funds.

"It’s no secret that there were problems in the Liu campaign in 2011," he said. "There’s an old saying about where there’s smoke. Sometimes, where there’s smoke, there’s smoke and no fire."

Connor also argued at the meeting that the board had violated its own rules by only giving Liu eight days to respond to complaints about invalid matching claims. Comparatively, Connor said, other campaigns had 32 months to correct information on what he argued were technical mistakes.

He also argued that the independent, 139-page report conducted by Thacher Associates, LLC., incorrectly interpreted finance law and discriminated against donors based on presumed income levels.

The board did not respond to inquiries about the report's timeline.

Regardless of the report's criteria, however, Connor argued that the board's penalization of the campaign and donors because of two individual's misdeeds could be the Liu campaign's final blow.

"A complete denial of matching fund is the equivalence of imposing the death penalty for pickpocketing," Connor wrote in response to the Thacher report last week. He again invoked the death penalty metaphor at the hearing.

Some Liu supporters said they would work to raise more funds outside the public matching system.

Peter Killen, 75, was one of at least seven Staten Island residents and Liu supporters at the public meeting. Having donated $300 to the Liu campaign since late 2012, Killen — a retired police officer — said he was still committed to seeing Liu win the race.

"It was a kangaroo court," he said of the board, adding that he was surprised and disheartened by the ruling. "I'm going to try to get 5,000 more people to donate the maximum to make up for this travesty of justice."

Liu himself seemed equally resigned to the verdict, telling reporters that he wouldn’t “cry over spilled milk.”

"If any other campaign had been put up to this level of scrutiny by the Campaign Finance Board or by anybody else, I have no doubt that we would be head and shoulders above the rest in the amount of documentation," he said. "There's no question that there are some pretty powerful forces in this city who do not want me to be mayor."

Mayoral candidate John Liu (Thacher Report Final FOIL Distribution) by Gotham Gazette

GothamVotes: A Conversation With Mayoral Candidate Christine Quinn

NEW YORK — Christine Quinn could make history as the first woman and openly gay mayor of New York City.

The self-described aggressive City Council speaker has long been a front-runner to replace Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Even so, she will need to overcome powerful headwinds to get Democratic voters to turn out for her in the September primary.

Quinn became speaker of the New York City Council in 2006; her first strike of the gavel in Council chambers came at the cusp of Bloomberg's second term. Despite a long legislative record after 14 year on the Council, Quinn's reputation has been dogged by her largely unpopular decision to support Bloomberg's push to change the law so that he could run for a third term.

Since then, her stewardship of the legislative branch has been marked by her willingness to work with the mayor. As a result, her loudest critics say her cooperation with the current administration would make hers a de facto fourth term for Bloomberg.

That's not to say that Quinn has not stepped outside of Bloomberg's shadow on occasion, even leading on issues that rankle the Bloomberg administration. Especially over the past year, she's been at the helm as the Council asserted a degree of independence by overriding mayoral vetoes of the living wage, paid sick leave and vendor fine bills. The Council is positioned to do the same over Bloomberg's opposition to the police inspector general bill.

Quinn talked about that bill, her relationship to the mayor, how she’d work with her successor and more in an exclusive interview with the Gotham Gazette.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Let's start with one of the big things that the Council did last year: open data.

CHRISTINE QUINN: Yes, we love open data. And I love that the Council was a big part of that, though I want to give (Councilwoman) Gale Brewer credit where credit is due because she certainly was a driving force behind that. But, you know, it's interesting that something like open data can seem like it's wonky, silly or just numbers, but when we had the situation with the ambulance — we now have really good data on response rate. That's not the kind of thing they always had.

That matters, because knowing if what happened in Williamsburg was an outlier — doesn't make it okay — but it's a different situation if it's an outlier versus what was happening everywhere. So open data is really important in helping us figure out what needs to be responded to, how it needs to be responded to, but also hopefully more efficiently involving workers, advocates and others in the process of developing solutions to problems.

GG: Obviously we're still technically in the early days of the law, but so far the city agencies subject to it haven't met their first deadlines.

CQ: Not in total, but I think — I don't know if others would disagree — I don't think we see a lot of lawless response. I don't think we see agencies flipping the bird off to open data. I think we see more of it being a little more complicated, which underscores the need of it.

GG: On the topic of transparency, one of the chief complaints lobbed at your record is transparency in terms of budgets and member items.

CQ: Oh my God, are you crazy — it's the total opposite. No. You're going to want to rewrite the whole question. My office, my office and the entire City Council under my leadership has brought more transparency to the budget process than ever before. If folks want to say more is needed, I'm open to that constructive criticism.

But, look: when I got elected speaker, you had a long, chunky Schedule C. It was largely impossible to figure out what Council members got what amount of money, what groups got what amount of money. You can now go to a database and get all of that information with a few strokes of a key. Grants given from the speaker's office never before had names associated with them. That's all changed.

One of the areas I've struggled with — and maybe data folks can help the next speaker on this — I'd love there to be more information on what the grant is funding. Because these two or three sentence descriptions are accurate but they're not particularly illuminating. I would also love — and this is challenging — but let's say a group is supposed to run after school programs and take care of 30 children a month. I'd love to be able to put online who met their goals, who didn't meet their goals. Who exceeded their goals. I'd like to be able to merge Council data with agency data so you know who got unsatisfactory, you know who got unsatisfactory. And that getting unsatisfactory puts those groups' funding in jeopardy.

GG: But people are starting to throw the words "slush fund" around and pointing to members items being allocated towards former Assemblyman Vito Lopez's nonprofit, or the investigation into Councilman Dan Halloran.

CQ: Well, look, there is a totally different, night-and-day difference from the system I inherited. I inherited an honor system where the assumption was that any group that a Council member requested to fund was a quality group. I found out fairly quickly that was a broken system. I asked for help from law enforcement, the Department of Investigation, and we've changed that system completely.

And what Dan Halloran was allegedly trying to do would not have been doable. So I took the problems we had very seriously. And we've completely changed the system with the Council's verification process, the Mayor's Office of Contracts verification process and a lengthy list of additional rules. It's important because we know there are bad people who are trying to steal money in the budget, and it's outrageous that anyone is trying to misuse that money.

But when you're an elected official you're going to have problems come across your desk. I believe you're judged by if you admit the problem, do you ask for help? Do you fix it and come up with a solution? Those are the things I did and I'm extremely proud of it.

GG: The budget dance — you've said before it's not something that you engage in, that it's something you're forced into.

CQ: It's going to end when I'm mayor. Because I'm going to put out budget that are a reflection of my priorities and a reflection of the actual state of the finances of the city. There have been many years that I've been speaker working with Mike Bloomberg where he had no choice but to propose cutting the budget because we were in deficit. But there were other years where Mayor Bloomberg proposed to cut everything out of the budget that the Council put in. That's not based on the economic reality, because those cuts weren't necessary.

A budget is the most significant statement of your priorities, and we need a budget put out by a mayor that reflects those priorities.

GG: To that end, how would you deal with some of the larger ticket, long-term times like pension and healthcare costs?

CQ: Those are going to be some of the things that are squarely on the table with the union negotiations. They need to be addressed between the mayor and the unions, but that doesn't mean that the larger expenses by city agencies, the larger capital parts of the budget shouldn't be looked at more globally in the budget process.

GG: You've had a couple of dances yourself with the mayor. What qualities do you want in whoever succeeds you as speaker?

CQ: I want for the next speaker to be someone who really believes in and respects the institution. I hope the next speaker shares my belief that you get more done working with the mayor than being constantly in disagreement with the mayor just for the sake of disagreement. But I know whoever the next speaker will be, they'll be someone who when we can't agree, we'll disagree agreeably.

We had days when all the Council did was disagree with the mayor just to get in the papers. I hope we don't go back to that, but I also recognize we're not always going to agree.

GG: One of the issues that you've agreed with the mayor on is your opposition to the expansion of the racial profiling ban. As mayor, is it something that you'd try to fight?

CQ: Obviously as mayor, I'd have to respect the laws that get legally established, even if you disagree with them. I'm very excited, actually, about the inspector general and potential it has to get more good information about how to run the police department better.

GG: The debate over the Upper East Side waste transfer station has really become one of the standout issues in the race.

CQ: Yep.

GG: You've said before that you wouldn't want something in another neighborhood that you wouldn't have in your own district. There's a difference, though between what's going on in the Upper East Side and at the Gansevoort station: the Upper East site would be a waste transfer whereas the other is a recycling station.

CQ: Yes, but in essence it is the same thing. There will be a facility that garbage trucks will come in and out of and tip garbage-related elements onto barges. In the Upper East Side it will be garbage; in the West Village, it'll be recycling. But the issues is the same: a facility, trucks, using the river in a park. They're probably two of the facilities in the entire plan that are the most similar because of their relationship to park spaces — different kinds of park spaces.

GG: If that's the case, though, would you entertain the idea of switching the two stations?

CQ: The plan needs to move forward. The plan needs to move forward as is. And that's what I'm going to do. There's not value in changing the plan. This plan took decades to implement, and people who don't want something in their neighborhoods, throwing in red herrings and lawsuits, switch this for that, or go put another facility on the west side of Manhattan — that would cost another $300 million give or take. They're just throwing out red herrings because they don't want to do their fair share. Period. End of conversation.

This plan is going to be implemented when I'm mayor.

GG: On public transportation, you've come out in support of expanding almost every form of mass transit: buses, bikes, ferries. And you've come out in support of taking mayoral control over the MTA. How exactly can the city under a Quinn administration handle that kind of responsibility?

CQ: Right now, we're taking more than our fair share of the burden because we don't have the right share of our voice on the board. We are the economic engine of the MTA, paying for more than our fair share and we have the voice of a piston. Those days need to end.

Bus rapid transit, select bus service — it doesn't cost anywhere near what it costs to build a subway. Ferries do take a subsidy — there's no way around that. And mass transit takes subsidies. But the effectiveness of those subsidies are done right in a multimodal, inter- and intra-borough way, we're seeing how effective it is. And as usage grows, the subsidies will obviously decrease.

GG: One of the big collaborative projects that's already happening between the state and the city is Sandy reconstruction. What's your take on waterfront development given that the state isn't a fan but Mayor Bloomberg is?

CQ: We're a city of islands. So we need to develop responsibly in a post-climate change environment. But we can't retreat from our waterfront. Now that doesn't mean you develop everywhere and every way. There are neighborhoods in Staten Island that want to be bought out, and we have an obligation to respect that. But we also have an obligation to respect the voices in Breezy Point and other places that say "we want to rebuild."

It's about not doing it where it's irresponsible, and where you do do it, doing it with requirements, materials and standards that make it as safe as possible.

GG: Along the same lines of development, one of Mayor Bloomberg's legacies really is going to be zoning policy. So what's your vision on zoning post-Bloomberg?

CQ: I think that's very true. One of the things that the mayor is known for is big rezoning projects. In some places, those have had great positives. In others, folks would argue some of the promise was not fulfilled. I'm probably going to start with a more neighborhood-based focus.

I really want to seize the potential of our neighborhoods to build 40,000 new middle-income housing units. I want us to seize the potential of our neighborhoods through my Keeping Opportunity Close to Home plan — KOCH, in case you didn't get that — to incentivize neighborhood economic development.

So I think you're going to see a bit more of a neighborhood opp versus big zoning down vision.

GG: Finally, as speaker, your Council's had a significant record on immigration, whether it be dealing with the city's deportation policy or naturalization programs. How would your immigration policy carry over if you're elected mayor?

CQ: Well, this is an immigrant town. My grandparents came here from Ireland 100 years ago, give or take — all four of them. If you had met them, they literally talked about this city as magical, that it had mythical powers. You gotta put yourself back in time — they left Ireland with no belief they would ever go home. But this was not just America — it was New York, a place you went to where you have the potential to be free and get out of poverty.

And that happened for all four of them. And I want to keep New York that place so that other Quinns and Callaghans and Lancers and Shines of the 21st Century and come here and have that same potential. One of my grandparents had an eighth grade education, most had second or third. But all of their children went to college. Now, it's different than it was then, but I want to keep that potential.

Superstorm Sandy Shapes Southern Brooklyn City Council Race

NEW YORK — Like many seaside communities in southern Brooklyn, the neighborhoods of the 48th City Council District were in the path of Superstorm Sandy when it struck nine months ago.

Manhattan Beach was engulfed in waves from the Atlantic Ocean in the south and from Sheepshead Bay in the north. Along Neptune Avenue, which runs through Brighton Beach, the floodwaters rose in some parts to about 10 feet when the hurricane reached its peak.

Nine months later, residents and local leaders are asking what will happen the next time a major storm sweeps through their communities.

That discussion is helping to shape the fiercely contested City Council race for the 48th district, which includes parts of Brighton Beach, Midwood, Sheepshead Bay and Gerritsen Beach, and is home to strong Russian, Arabic and Orthodox Jewish enclaves.

Six contenders are vying to replace term-limited Councilman Michael Nelson: Community Board 15 Chairwoman Theresa Scavo; Nelson aide Chaim Deutsch; district leader and journalist Ari Kagan; attorney Igor Oberman; attorney Natraj Bhushan; and former state Sen. David Storobin. The primary is Sept. 10.

While the five Democratic candidates interviewed for this story say they don’t have exact plans for preparing for future extreme weather, all agree that it is a priority. Storobin, the lone Republican, didn’t respond to requests for interviews.

Scavo said that if she gets elected to the Council her first piece of legislation would call for giving property tax credits to homeowners if they install backwater valves to prevent flooding from the sewer system. She said the valves could cost between $1,500 and $2,000 each.

“A lot of the problems that occurred here was sewer back up because the sewers are so small they couldn’t handle the heavy downpour of rain plus water from the bay and the ocean,” said Scavo, 61, who besides her work for community board 15 volunteers her time to numerous local organizations. She has been endorsed by the Southern Brooklyn Democrats.

Igor Oberman, the board president of the Trump Village West co-op in Brighton Beach and one of three Russian-born candidates in the race, said he had seen proposals for safeguarding the beaches but wasn’t ready to pass judgment on them.

“I have to say I have been trying [to] wrap my head around them,” said the 40-year-old candidate, who records show made a $250 donation to Storobin’s 2012 state Senate campaign but as a Democratic has earned the support of progressive groups including the Working Families Party and 32BJ SEIU. “Several months have gone by where they have talked about should we do it like New Orleans [did] it with levees. I’m not sure … But we need to start having a much more serious discussion.”

Fellow Russian-born candidate Kagan, who is expected to get the support of influential local Russian American media mogul Gregory Davidzon, suggested opening beachside kiosks where the profits would go toward improving infrastructure in the district. Each neighborhood would have its own store, he suggested, that would sell items like sunscreen, goggles and water, and rent equipment like umbrellas, chairs and surf boards.

“Sandy affected our district big time, especially the south part of the district. We are still recovering. We have very old outdated sewer system and surge systems,” said Kagan, 46, who has been endorsed by a handful of liberal organizations, including the United Federation of Teachers.

Kagan and Storobin are seen as archenemies in the race, each fighting to sway the Orthodox Jewish vote.

For Bhushan, the youngest of the candidates at 27, Sandy was his main reason for jumping into the race. He said he was particularly concerned about how money for storm recovery would be distributed. “Do I have a particular plan in place? No, I don’t, but a particular plan is something I would like to craft,” said the long-shot candidate who has little in the way of financial or political backing from the establishment.

A citywide report on the effects of Sandy released by Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration in June detailed how most of southern Brooklyn was prone to flooding because of the area’s bays, creeks and inlets. Homes and buildings in Manhattan Beach and Sea Gate were battered because there was no coastal protection. The beaches lost 272,000 cubic yards of sand.

As part of its plan for building a more resilient city, the Bloomberg administration has proposed replacing about one million cubic yards of sand around the coastal areas and raising barriers in low-lying areas at risk of flooding.

Deutsch, who has worked for the City Council for 17 years and is founder of the Flatbush Shomrin — a neighborhood watchdog group made up of local Jewish residents who are unarmed and serve as “eyes and ears” for the police department — said he wants to make sure any proposals are safe for residents and that there is sufficient funding for the plans.

“There are a lot of answers we still have to look forward to, and how it is going to be paid for,” said Deutsch, 44, who has been endorsed by Nelson. “We have to plan, and not just a plan that is good on paper but a plan that makes sense.”

He said more talks are necessary before he can back any plans.

Scavo said she plans to use the power of her voice to make sure investments in the district help the district to prepare for future extreme weather.

“You get out there in the street and rally the truth,” she said. “Your mouth will get funding here. We need someone to lead the people to ask for help, and right now it’s very quiet.”

Of the candidates, Oberman is leading in fundraising with over $100,000. Scavo is the only candidate who comes close with over $95,000 in her war chest. Deutsch has $77,000, and Kagan has almost $76,000. Storobin, who was endorsed by Republican mayoral frontrunner Joe Lhota, filed his first round of fundraising with $45,000. Bhushan, who has said he is not focused on fundraising, trails with almost $4,000.

All of the candidates, except Bhushan, have received campaign contributions from developers, attorneys and construction companies — not surprising, given the number of homeowners in the district.

The candidates will receive six-to-one matched donations through the public campaign finance system. The next filing deadline is Aug. 9.

48th City Council District Candidates

Natraj Bhushan, a longtime resident of the district and an attorney, graduated from City University of New York School of Law at Queens College. He was born in Oklahoma and moved to New York when he was 6. He interned at Councilman Leroy Comrie's office in 2008, and gave free legal services to Nelson's office during Superstorm Sandy.

Chaim Deutsch, who has lived in Brooklyn all his life, organized a group of Jewish volunteers as the Flatbush Shromin neighborhood watchdog group in 1991. He is currently aide to term-limited 48th district City Councilman Mike Nelson and has worked for the Council for 17 years.

Ari Kagan was born in Russian and moved to the United States over 20 years ago. Since moving to Brooklyn, Kagan has worked as a journalist for a Russian newspaper and hosts a Russian TV show. He was an aide to city comptroller and mayoral hopeful John Liu as well as Congressman Michael McMahon. He graduated from Baruch College.

Igor Oberman fled with his family to the United States in 1981 from the former Soviet Union to avoid religious oppression. He was 8-years-old. Since moving to Brooklyn he became the first of his family to graduate college and went on to obtain a law degree. He has served as a judge at the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings and worked for Borough President Marty Markowitz as a liaison to Russian and Jewish communities. He is also the board president of the board of directors of Trump Village West co-op in Brighton Beach. He graduated cum laude from Brooklyn College and attended New York Law School.

Theresa Scavo, a former public schools teacher, has been a member of Community Board 15 for 13 years and has been chair since 2006. She is also the vice president of the High Way Democratic Club. She owned a retail business for 26 years. A life-long resident of Brooklyn, Scavo graduated from Hunter College and went to Richmond College for her master's degree.

David Storobin is a Russian native who is a real estate broker and an attorney. He ran for state Senator and won only to serve for 11 days because his district was eliminated after the district lines were redrawn. He is vice-chairman of the Kings County Republican Party. He received his law degree from Rutgers University.

GothamVotes: Thompson On Stop-And-Frisk, Racial Profiling And The Next Comptroller

NEW YORK — Bill Thompson nearly stole Michael Bloomberg's third-term dreams away in 2009. This time around, he’s the only black candidate in the race. Unencumbered by any major political scandal or unpopular policy decision, such as extending term limits, he would seem to have frontrunner status all but pinned down.

And yet Thompson has struggled to stand out among this year’s Democratic candidates, often polling in the middle of the pack. That may have begun to change in recent weeks.

Following criticism from some that he had taken a too moderate stance on the New York Police Department's stop-and-frisk tactics, Thompson has become more outspoken on issues of race and policing. The day after a Florida jury acquitted 17-year-old Trayvon Martin’s shooter, George Zimmerman, Thompson’s campaign tweeted, “Trayvon Martin was killed because he was black. There was no justice done today in Florida.”

Yesterday, he delivered a speech on race, again invoking Martin’s death and linking it to issues close to home.

“Here in New York City, we have institutionalized Mr. Zimmerman’s suspicion with a policy that all but requires our police officers to treat young black and Latino men with suspicion, to stop them and frisk them because of the color of their skin,” Thompson said.

We interviewed Thompson exclusively on a recent Friday before he was set to spend the night at public housing in East Harlem with a handful of other Democratic mayoral hopefuls in an event sponsored by the Rev. Al Sharpton's National Action Network. He spoke at length about his position on stop-and-frisk, racial profiling, educational policy including mayoral control, sustainability and how he expects to work with the city's next comptroller (even if his name just happens to be Eliot Spitzer).

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Before we started this interview, we were talking about the various problems plaguing the city's Public Housing Authority, from the failure to install security cameras at developments to making much-needed repairs. Do you want to finish your thoughts?

BILL THOMPSON: The thing that has made it even more outrageous is the fact that they have money — and clearly not the money that's necessary to bring things to the level that it should be — but they sat on a billion dollars. And those are dollars that could have been used for renovation, dollars that could have been used for the upkeep and maintenance, dollars that could have been used to fix elevators, dollars that could have been used to get rid of mold and to fix leaking plumbing and other things.

GG: What do you think of the Bloomberg administration's plan to take care of the backlog of repairs?

BT: The thing about it is that you continue to be told that things are gonna be improved ... If it hasn't been done up to now, why would it be done? At least to the level that it needs to be. I mean, looking at the security cameras where you had $42 million. That wasn't installed. There was a commitment made on that. And it's clear that — I think, if I remember correctly, of dozens of developments that are supposed to have security cameras installed, they have only done eleven. I need to go back and look. I don't remember the exact number. But that's not on target. All of that together, you know, why would we believe that it should get done by now?

GG: What would you do differently than the Bloomberg administration?

BT: I think it's looking at not just the backlog but also what do you do better moving forward? At this point, how are repairs done? I mean, most have been done at a central location. Clearly that hasn't been working. Not being there right now and not exactly knowing how they are going about it, it's clear you have to change that, it's clear you have to start to create more of a list of priorities.

And, another thing, they have been sitting on money. And I think that's the thing that angers people even more. While there's necessary repairs that need to be made, they sat on money. And not just a little. You know, a billion dollars. And just a number of things that have occurred in the Housing Authority that are just incredibly unfair.

When you look at the money that comes off the top every year — take $75 million off the top for police protection — I don't see that happening any other place. People in the Housing Authority pay taxes also. Why this kind of double billing? I would eliminate that. I am not going to take money off the top.

GG: In some articles on your position on stop-and-frisk, you have said there has been an "overreaction" to the policy. Can you explain further your position on police stops?

BT: Here's what I meant. What I've said all along is that stop-and-frisk has been misused and abused by this administration. That when people are being stopped only because of who they are and what they look like, there's something wrong.

If I'm the mayor of the city of New York, people aren't going to be profiled. We aren't going to have stop-and-frisk continue to be misused. My police commissioner isn't going to misuse it the way it's been done. It's not going to be tied to performance goals. It will become a policing tool. That's exactly what it is. You don't want to eliminate it.

GG: What do you think about the Community Safety Act, which includes a bill to strengthen anti-racial profiling by police?

BT: Profiling is illegal. It isn't supposed to occur. Rather than just having legislation that perhaps adds additional bureaucracy, why don't we just have a mayor that won't engage in these practices? That won't allow people to be profiled? That will make sure that doesn't occur? That's the kind of mayor I want to be. I don't need the additional bureaucracy or the additional problems. I understand the legislation is moving forward. Everybody is frustrated. Everybody is tired of what's occurred.

The point I have been trying to make is that I would not need the additional legislation to be able to get rid of the way that stop-and-frisk has been misused. I would not allow people to be, in the city of New York, to be profiled. If you allowed that, you wouldn't be my police commissioner. I would terminate my police commissioner.

GG: Looking at Bloomberg's legacy on education, what policies would you keep? What would you reject?

BT: I would give the mayor credit for seeking mayoral control and for getting it. I've been supportive. I've testified in front of the City Council when it was moving forward. I think he should be given credit for getting mayoral control.

I think for looking to try to reform things and change bureaucracy, I will give [him] credit for that. And for the focus on education, attempting to be the education mayor. I will give him credit for that.

On the other side, I think they have failed in a number of ways when it comes to education. The excessive focus on standardized testing. Robbing the school system of content. In a lot of ways sacrificing it for, in search of, better scores on standardized testing is a mistake. And also underestimating how important it is to afford an educational vision and have an educator at the head of the system. That's one of the things I've said I would do. I want to have a chancellor who is an educator. Who is a classroom teacher. Who understands the structure. Who knows how to put forward a strong educational vision for the City of New York. Who knows how to engage people. We haven't seen that in many years.

GG: Turning to sustainability, would you, as mayor, call for a retreat from the coastline?

BT: There's not a one size fits all. If you look at some places like Sea Gate, where someone has said "Wow, it's flooded before,” they'll talk to you about the need to do more seawalls, or seawalls again. But seawalls got breached. But it's an opportunity to rebuild. Coney Island? We're not going to walk away from Coney Island. At the same point, what can you do differently?

Things I've recommended that I want to do: a deputy mayor for infrastructure and construction. There's an opportunity to coordinate this. We're getting money from the federal government and from FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Administration]. You have city capital dollars. There's money from the state. Private dollars. Dollars from utilities. We need to coordinate this. So that when you look at neighborhoods, when you look at seaside comminutes … making sure that in the next extreme weather pattern, they are prepared. So you're not going to rebuild everything at once. It just doesn't make sense.

GG: As comptroller, what do you think were your top three achievements?

BT: I think that it was an office that was a different office when I left. That was a more aggressive office. That it was an office that involved itself in things other than the bottom line.

Whether it was working in shareholder rights on one side, being an incredibly aggressive office … whether it was a comptroller that got involved in education, public safety, you name it, there wasn't an issue that the office didn’t get involved in. And before I was there? It was … the comptroller was involved in the books and the bottom line and a bunch of other things. After that? It was an activist office.

I was a frequent critic of some of the direction we were going in, and there was a question of fairness and equity across the city. You talk about budget cuts cross the boroughs ... You looked at neighborhoods and crime was going up in neighborhoods, I had no difficulty talking about that.

GG: How would you as mayor relate with the comptroller's office?

BT: It's starting out with a healthy, respectful comptroller's office as an institution, and understanding that we're not always going to be on the same page. There is some … almost built-in tension between the office of the comptroller and the mayor … and there are a lot of things that you can work on together. But you are going to disagree and you are going to bump heads. That's just kind of the nature of the job.

GG: What would you do about a comptroller who seeks to make the office even more of a platform, who is even more aggressive? How do you deal with that as mayor without there being political gridlock?

BT: The one thing about the system? It's designed to prevent gridlock. One of the things I found frustrating, as comptroller is that sometimes, even if you disagreed, the mayor can move forward. It is a very strong structure.

GG: A lot of people say Bill Thompson’s a “really mild guy, he doesn't stand out to me.” What do you think stands out about you?

BT: Perhaps the one thing that's overlooked, on behalf of the people of the City of New York, on issues of principle, I will always stand up. I was at the Board of Education as its president, and took on Rudy Giuliani. People believed he couldn't be beat over who the next chancellor of the education system was. And I stood up in spite of the fact that people thought I was crazy for doing that. It was the right thing to do. It was what made sense for our children.

I've always led, and I've never been scared to lead the city. I wouldn't end up being the mayor who screamed at people, but I would be the mayor who stood for the people of the city.

South Asians See 'Tipping Point' In 2013 NYC Elections

NEW YORK — In the early 1970s, Amol Sinha’s parents moved to the United States from the state of Bihar, India. Sinha’s father came to pursue an education and later work as a statistician. His mother stayed home to raise their three U.S.-born sons.

When Sinha’s parents came to the U.S., the South Asian community was disparate and far-flung. South Asians lived in small, isolated areas, and rarely saw other people who looked liked them in their daily lives. Over the next 40 years, the Sinhas saw their fellow South Asians grow in number, form enclaves and flourish in fields such as science, technology, law and business. At 28, Sinha is a lawyer with the New York Civil Liberties Union. His two older brothers are doctors.

But while South Asians have succeeded in a wide variety of industries in the city, Sinha said he longs to be able to call a city elected official one of his own. There is currently no South Asian on the City Council or in citywide office. That could change this year, with a number of South Asian candidates running for Council and — perhaps most notably — Reshma Saujani in a tough race for the citywide office of public advocate.

“To see somebody take a risk and actually do things to serve communities in public interest, or public service, is certainly inspiring and motivational,” Sinha said. “And the more that becomes the norm, the better it will be.”

But while some South Asian candidates say this year could be a “tipping point,” and the 2010 Census puts the population of South Asians in New York City at a robust 300,000 or more, there is no guarantee of victory at the polls.

Activist groups say that this is in large part due to the way district lines have been redrawn, splitting up South Asian communities of interest. There is also the fact that the South Asian community in itself is not a monolithic mass.

The community encompasses a number of diverse cultures, languages and religions: Someone of South Asian descent could be from a whole host of different countries, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bhutan, as well as countries with large diaspora populations, like Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname and Uganda.

So how can a South Asian candidate win in this election season?

Saujani, an Indian-American who previously launched the nonprofit tech organization Girls Who Code and served as deputy public advocate, said it was critical to campaign for more than just the South Asian community if she is to have a chance at getting elected.

“So it’s not like, ‘You’re Asian so I’ll vote for you, or you’re black so I’ll vote for you,’” Saujani said. “It’s, ‘Will you fight for my issues?’” And Saujani, whose family came to New York from Uganda as refugees, said she inherently understands these issues due to her background.

“I think the powerful thing you’re seeing with this next generation of leadership is many of us are first-generation Americans,” she said. “We’re so tied to the American dream, so tied to creating the American dream.”

Saujani’s opponents include politically influential Councilwoman Letitia James and state Sen. Daniel Squadron. Saujani is very much the outsider candidate, with not as much name recognition as her two opponents. That said, when the deadline came for candidates to file their petition to get on the ballot, Saujani’s campaign said they filed over 45,000 signatures — 12 times the required 3,750. Of course, not to be outdone in the slightest, James’ campaign said they filed around 70,000.

But Saujani’s campaign manager, Michael Blake, a former aide to both Obama campaigns, is not worried. He said she will “absolutely” win.

“She is not just coming at it in a policy perspective, she’s coming at it in a personal way,” Blake said. “And people understand that, they relate to that.” Saujani’s background and immigrant status is key to the way her campaign is engaging with voters. This is perhaps an effort to use her outsider status as an advantage, by saying that this is a candidate not entrenched in the political system.

“This is a citywide grassroots organization in the same way we built the Obama model, which clearly worked,” Blake said. “We’re going to do that here.”

John Albert, an organizer with Taking Our Seat, which seeks to empower South Asian voters, said finding unifying themes in the American political context could mean all the difference for candidates between winning and losing. Forming coalitions of voters has long been considered the road to elected office in such an ethnically diverse city as New York.

“I think the South Asian community poses some unique challenges,” Albert said. “We’re fractured in so many more pieces. There may be different types of Latinos, but Spanish brings them together. We don’t have that particular connection.”

Some South Asian candidates argue, though, that the lines of division within the South Asian community in the city are much more blurred than the borders between those of its home countries.

One prominent South Asian candidate who recently bowed out of the election is Abe George, who was running to be the next Brooklyn district attorney against longtime incumbent Charles Hynes.

“You come to Brooklyn and, on Coney Island Avenue, the Pakistanis and the Hindus are getting along,” George told the Gotham Gazette before deciding to drop out of the race last week and endorsing his opponent, Kenneth Thompson. “But you go to India, and the Pakistanis and the Indians are fighting. I think it’s different here in America because we’re so outnumbered that you come together.”

Regardless, Albert said, overcoming potential differences within the community is hugely important because of the power in numbers.

“Much of our work early on was to go to communities and say, ‘Yes, you can be Bangladeshi, you can be Pakistani, you can be Punjabi,’” he said. “But it’s more politically empowering to say we’re South Asian.”

Candidates are also running on platforms that they hope will attract the minority vote in general. Albert says that, strategically, it is important for them to focus on Hispanic and black communities.

“We have to have an understanding that the South Asian community lives very close to the Latino community,” Albert said. “You’re more likely to have a Latino neighbor than anything.”

George, for example, was running a campaign that was strongly against the aggressive stop-and-frisk tactics of the New York Police Department, which have long been seen as targeted at blacks and Latinos. He had said that marijuana cases were a waste of time, and had he been elected, he wouldn’t have prosecuted anyone carrying only a small amount.

“I’m not going to wait for the state Legislature,” George had said, referring to efforts on the state level to pass a law that would decrease penalties for the possession of small amounts of marijuana. “I’m going to decide right now that I’m not going to prosecute those cases as a crime. Just as a violation. I’ve got bigger fish to fry.”

But Hynes said his office already didn’t prosecute for possession of small amounts of marijuana, during the first debate of the race. George called Hynes “a liar” when he said this. Regardless, not long after the debate, the pro-legalization National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws endorsed George over Hynes.

Helal Sheikh, a Bangladeshi former public school teacher from East New York who is running to represent the 37th City Council District, said he was very keen on capturing Latino and black votes. He said that if he were to just focus on the South Asian vote that the numbers in his district wouldn’t be there to get him elected, despite the large number of Bangladeshis who reside in East New York.

He also emphasized the importance of the South Asian community finally seeing political representation, but added that electing the most qualified candidate was still more important.

“I’m not running as a Muslim,” Sheikh said. “I don’t want anyone’s vote as a Muslim.”

First generation American candidates will also need to target the first-time voter base. South Asian candidates said they need to not simply campaign on the issues, but also spend some of their time and resources on get-out-the-vote strategies.

Adding to the challenges is the language barrier at the ballot box. While the city Board of Elections is mandated under the Voting Rights Act to provide ballots in Bengali to some of Queens, there is no requirement for Hindi or other major South Asian languages. Some candidates are doing voter outreach, alongside campaigning, to try and engage people in an effort to overcome the difficulties the South Asian community might face on Election Day.

“I’m going door-to-door, and asking who’s registered and who’s not,” Sheikh said, adding that he is working hard to get people registered to vote in his neighborhood. Sheikh said he believes his race will be decided in the primary, and that therefore a strategy that focuses on getting as many people registered as possible could tip the scales for him.

Natraj Bhushan, a lawyer with the Community Resource Legal Network who is running for the 48th City Council District, agreed that registering voters was critical for a win on Election Day. But he said that as a younger candidate — he is 28 years old — getting help from older and more experienced candidates had been very helpful when focusing on these types of strategies.

“To pick their brains, to know that anything can be accomplished in numbers is invaluable,” Bhushan said. He went on to add that he had even been discussing potentially sharing election lawyers with others.

Above all, South Asian community members and candidates stressed the significance of the symbolism of electing one of their own to office.