The 'Tina' Habit

Crystal Methamphetamine, known in New York City as tina |

To an outsider it might seem as if things couldn't be better for the hundred or so men, mainly in their 30s and 40s, crowded into a fourth floor room at the Gay and Lesbian Center in the West Village. The room rocks with laughter, hugs are easily exchanged, and plans are made for dinner or weekend outings. But this is the Tuesday evening meeting of Crystal Meth Anonymous, and many have not been doing so well.

Peter, one of the city's top real estate brokers, who managed to keep his job despite a serious crystal addiction, recalls being holed up in his Chelsea apartment with the blinds and shades drawn at mid-day so paranoid that he thought the CIA had bugged his apartment. "I was convinced that I was going to be arrested for spying," he says.

This is the harsh reality of crystal, a form of speed (methamphetamine) that stimulates the brain's pleasure neurotransmitters and that experts say is as addictive as crack or heroin.

It is called crank on the West Coast, where it was popularized by the Hell's Angels in the 1960s. It is a huge problem in rural America, according to the National Institutes of Health.

But in New York, it is called tina, and it is almost exclusively a phenomenon among gay men.

Three years ago, there were two Crystal Meth Anonymous meetings in New York. Today, there are more than 20. All of them are geared toward gay people; there are no "straight" meetings in New York. In a 2002 study by the AIDS Education and Training National Resource Center, 50 percent of gay men in New York who admitted to using drugs said they had tried crystal, up from 10 percent in 1998.

Crystal's popularity in the gay community is tied in part to the explosion of circuit parties, multiple-day dance club affairs like New York's Black Party at which the ability to stay awake and stay high is highly prized. One bump of crystal induces a sense of euphoric power and keeps the user awake for up to a day, though the crash is psychologically and physically debilitating, causing depression, irritability, anxiety and paranoia.

Several studies have linked crystal abuse, risky sexual behavior and HIV transmission, which has been on the rise in the gay community after leveling off in the late 1990s. "The abuse of drugs, particularly crystal, and HIV transmission are undoubtedly linked," says Michael Siever, director of the Stonewall Project, a drug education and counseling program.

For HIV-positive men, crystal's wearing down of the body's immune system caused by missed meals, vitamin depletion, weight loss and lack of sleep can trigger the onset of AIDS. An Ohio State study has shown that methamphetamine stimulates HIV replication in brain cells as much as fifteen-fold.

Crystal's ravages are made worse by activities like binge partying--a fairly common phenomenon among gay addicts--where the user is awake for days at a time, crashes for several more, and then starts over. According to Life or Meth, binge partying is driven by a compulsive desire for sex, which in turn is driven by crystal abuse.

According to Robin Cato, executive director of the Council on Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, gay men who often live alone are vulnerable to acting out their feelings of isolation and loneliness by abusing drugs and compulsive sexual behavior.

Bars, clubs or bathhouses become too time-consuming for most crystal abusers, so, while their habit may have been picked up in the clubs, they rely on the Internet to score. It is not difficult to find somebody in the same neighborhood, or even on the same block, looking, in the vernacular of the Internet, to party and play--PNP.

For many addicts, staying off crystal, while the most challenging hurdle, is just the first of many they face. "For years I only had sex when I was high on crystal," says Bill, who has not touched drugs or alcohol in almost two years. "During my first six months of sobriety I was celibate. I had to be. Now it is a struggle to have an emotionally healthy sex life."

*****

Related Article

• Nightclub Act II - A new wave of nightclubs is hitting the city, some in the same locations where notorious nightspots were shut down a few years ago for drug use, noise, or being a nuisance. This time, though, new laws could prompt club owners to take a new -- and cleaner -- approach.

Nannies

Like many New Yorkers, Maureen Alleyne could easily surround herself with nannies in New York, simply by walking into any bookstore or turning on her TV.

Like many New Yorkers, Maureen Alleyne could easily surround herself with nannies in New York, simply by walking into any bookstore or turning on her TV.

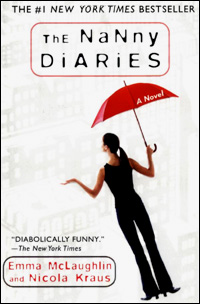

In a bookstore, she would see a stack of The Nanny Diaries, by former nannies Nicola Kraus and EmmaMcLaughlin, a bestseller - soon to be a movie -- about a beleaguered NYU student/nanny who suffers countless indignities at the hands of Mrs. X, a rich, spoiled and selfish Park Avenue mom who doesn't work, yet somehow has no time to raise her child. Also on the shelf, she could get You'll Never Nanny In This Town Again!, Suzanne Hansen's Hollywood nanny memoir; apparently, the public can't get enough of rich people behaving badly toward their white, college-educated help. Looking on a cybershelf - an e-book - she would find Searching for Mary Poppins by Judith Lederman. In December of 2004, audiences will be able to devour more of the myth: Mary Poppins the musical is scheduled to open on the London stage.

If she wanted a more realistic portrayal, she could attend Lisa Loomis's new Off-Broadway play, "Living Out," which centers around the relationship between a lawyer-mother and her employee, a nanny from El Salvador.

But, unlike most New Yorkers, Alleyne, 57, who is originally from Barbados, surrounds herself with nannies in a different way. She is herself a longtime nanny. "I haven't had too many bad experiences," she says of her work. "But you always have some." She feels strongly about the rights of her fellow nannies, rights which are too often left to chance and the whims of employers. Nannies, she says, "should get more respect and dignity." So, every third Saturday of the month, she attends a meeting of a group called Domestic Workers United , a city-wide alliance founded in 2000 to promote "fair labor standards," as the group puts it, "in an industry where abuse and exploitation are the norm."

Recently, the City Council unanimously passed a bill, pushed by Domestic Workers United, that requires employment agencies to inform all domestic workers of their rights, and requires employers to sign a statement saying they understand the rules on minimum wage, overtime, and Social Security. But, as in the civil rights movement before it, new legislation to address the issues of domestic workers can only be effective if attitudes change as well.

So, on November 1, Domestic Workers United is holding what it calls a convention, what others might see as a rally, expecting to attract at least a thousand nannies to help bring their issues to the public - complex issues tied up in race, gender, class, and immigrant status, as well as in the complicated relationship between employer and employee, with its blurred boundaries between work and family. "People who don't understand," said Alleyne, "need to be educated."

"THE NANNY" VERSUS THE NANNY

Children of the privileged have always had nannies in one form or another. Sometimes they have gone by the name of wet nurse, at other times, governess - and one only has to read Jane Eyre to know how that situation can turn out. The Vanderbilts and Astors of this city certainly weren't raised by their mothers; instead, that job generally fell to British nannies. (If the household considered itself progressive, the nannies were French.)

Children of the privileged have always had nannies in one form or another. Sometimes they have gone by the name of wet nurse, at other times, governess - and one only has to read Jane Eyre to know how that situation can turn out. The Vanderbilts and Astors of this city certainly weren't raised by their mothers; instead, that job generally fell to British nannies. (If the household considered itself progressive, the nannies were French.)

But as everyone knows, women have entered the workforce in ever-increasing numbers, creating a growing need for childcare. The Urban Institute estimates that in 1999, nearly three-quarters of children in the U.S. under five years old whose parents were employed were cared for by someone other than a parent. Most such families must struggle with day care. Those who don't qualify for city-funded daycare have to find other, usually more expensive, options; some are forced to pay $9,000 for a year of private daycare

Only four percent of the children of employed parents nationwide were cared for by a nanny or babysitter. In New York, home to more affluent couples, the figure is roughly five percent. Not surprisingly, two-income higher-earning families are the most likely to enlist nannies.

Ai-Jen Poo, an organizer with Domestic Workers United, estimates that there are 200,000 domestic workers in New York City, and about 600,000 in the metropolitan area. Despite their popular depiction, white nannies are in the minority, she says. Most nannies come from Third-World countries in Asia, Latin America and the English-speaking Caribbean, some illegally, though it is hard to get an exact figure

If your primary exposure to nannies is through reruns of Fran Drescher's sitcom, you are probably unaware that most nannies work grueling hours for little pay, and sometimes endure horrible treatment.

UNREGULATED INDUSTRY

The problem, Poo says, is that the "the industry is completely unregulated. Everything is up to the whim of the employer." Nannies can generally earn anywhere from about $200 to $650 per week. They may or may not get overtime, sick days, or vacations. Ironically, many must leave their own children in their native countries and send money home; others rely on friends, family members, or after-school programs for their own childcare.

The problem, Poo says, is that the "the industry is completely unregulated. Everything is up to the whim of the employer." Nannies can generally earn anywhere from about $200 to $650 per week. They may or may not get overtime, sick days, or vacations. Ironically, many must leave their own children in their native countries and send money home; others rely on friends, family members, or after-school programs for their own childcare.

Some nannies do not live with their employers, coming to work before their employers leave for their jobs, and not going until after (sometimes long after) their employers get home. But others live in, a situation that is ripe for abuse. Such workers, Poo says, "have no time to themselves, they never leave work, they're always on call. ...That informality and flexibility is always at the expense of the worker." Even the most well-meaning employers may end up taking advantage of their employees in the absence of any clear guidelines.

While it is difficult to say how many nannies live in, Poo says that the highest concentrations of live-ins used to be in the suburbs, but families in the city are requesting that their domestic help live in with greater frequency, partly just because they know so many nannies desperately need the work.

Immigration status can also play a role in a worker's treatment. Even though illegal immigrants are entitled by law to the same basic worker's rights as citizens, many fear their employers will turn them in to the immigration authorities if they don't do whatever is asked of them. Mary, a nanny from Grenada who asked that her last name not be used, knows from experience that "if you don't have your papers they will work you to death." Eglan, a Barbadian nanny who also feared allowing her last name to be used, agrees that when it comes to employer demands, "sometimes you feel you don't have a choice."

Such workers feel that the nanny/employer relationship needs some clear rules. There are signs that change is happening. This past May, Domestic Workers United won a partial victory in their attempts to impose formality on the industry. The bill that the City Council passed empowers the city's Department of Consumer Affairs to enforce the new notification requirements. Councilmember Gale Brewer, the bill's chief sponsor, explains that the city doesn't have the ability to legislate labor law (that is a state function). The council also passed a resolution urging employers to abide by the advocacy group's guidelines, which would ensure five sick days, five personal days and two weeks' vacation a year.

Some of the employment agencies weren't happy about the bill, fearing they will lose business. "This legislation is asking the agencies to police the very people that are paying our fees," Clifford Greenhouse, co-owner of the Pavilion Agency, told the New York Times. "They're also asking people to commit to very rigid job specifications which change almost daily in a private home."

Poo of Domestic Workers United says that, if not all employment agencies are necessarily resistant to the new law, some seem to be ignorant of it: "We met with three licenced agencies in the last month who had not received the bill of rights and knew nothing about it." To Poo, though, the very existence of the law is encouraging: "It says change is possible in this industry." Domestic Workers United's long-term goal is to get the State Legislature to implement a standard contract (in pdf format)for all workers which would include sick days, personal days, and paid vacation.

EMPLOYMENT AGENCIES

The city law applies only to those workers who find a job through an agency; Poo estimates that no more than 40 percent do so, while the rest go through newspaper ads and word of mouth. Carlos Ramon, who runs Amiga Nannies an Internet subscription service, says that because of language or immigration issues, many prospective employees are afraid to go to the better agencies, which are often perceived as giving preferential treatment to white American or European applicants.

The city law applies only to those workers who find a job through an agency; Poo estimates that no more than 40 percent do so, while the rest go through newspaper ads and word of mouth. Carlos Ramon, who runs Amiga Nannies an Internet subscription service, says that because of language or immigration issues, many prospective employees are afraid to go to the better agencies, which are often perceived as giving preferential treatment to white American or European applicants.

The licensed agencies tend to place nannies in high-end homes, says Poo, who says an unknown number of unlicensed agencies have popped up in the city, though "only a few are notoriously bad."

The sketchiest outfits, Ramon says, will "take advantage of people with limited English skills. They'll charge a fee and send 10 ladies to the same place." Ramon charges $20 for a one-year subscription to his Web site; job seekers can post their profile and, he maintains, pick and choose their employer. Ramon also advises subscribers on minimum pay requirements: "For babysitting with light housekeeping, they should get no less than $350 per week, but really they should get $400. That's a bare minimum," he says.

A HOME AS A WORKPLACE

While it's true that there are some bad employers out there - who hasn't had a mean boss, after all - to be fair, many employers want to do the right thing. The problem is, they may have difficulty understanding that despite the personal nature of the work, it is a job, and their home is a workplace.

When Gayle Kirschenbaum first employed a nanny two years ago, "I struggled the way others do, determining what workplace standards should be." Kirschenbaum now belongs to Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, a group which has been working with Domestic Workers United to help raise employer awareness. She supports the standard employment contract, and says that "anything that standardizes practices is helpful on both sides."

Kirschenbaum believes that employers run the gamut, from those who don't care that they're exploiting their workers, to "those who want to imagine they're fair but aren't being so thoughtful." When she first saw the standard employment contract set forth by Domestic Workers United, she says "It just seemed so right. It made so much sense that anybody would have on paper the clarified terms for both parties. It eliminates so much confusion, so much subtext and stress." Plus, she adds that putting professionalism into the nanny/employer relationship doesn't preclude the personal - "when things are clear, it's easier to trust one another."

To that end, her organization will be launching the Living Room Project next year, a community effort to get people talking about the deep-seated issues and assumptions about gender and class involved in employing a domestic worker.

TEACHING NANNIES, AND LEARNING FROM THEM

It isn't just attitudes about employees in general; it's the very nature of the work nannies do - and sometimes the worker's skin color - that's at issue. Ai-Jen Poo feels that society's assumptions about the nature of women's work needs to be challenged. "Family and home are seen as natural," she says. "But every form of work requires thought." In order to help employees gain skills and respect, Domestic Workers United started a nanny school two years ago. In this six-week course, nannies learn from child psychologists, pediatricians, and other child care professionals. It costs $100, and Poo says some employers have paid for it. "The workers look at it as an advantage," she says. So far, over 250 nannies have graduated from the program.

There are also issues of racism; Poo says white nannies are 'the elite within the industry," and some agencies feed into that, advertising that they place "European nannies," a code word for white. Sometimes nannies can fall victim to that way of thinking, as well. Jane, a white middle-aged nanny in Park Slope, says "There aren't so many American nannies. I'm a dying breed." She says she's shocked when she overhears other nannies discussing things like health insurance. "They demand a lot of things," Jane says. "My ears are like, wow."

And Gail Kirschenbaum, a feminist herself, believes that many white women "haven't translated their feminist choices to valuing the caretaking labor of women of color in their homes." So, while raising awareness is important, Kirschenbaum believes "this isn't an issue of being a nice person. Any significant labor reform comes down to making it solid law."

Still, a good attitude certainly helps. Gail, a 42-year old nanny from Trinidad who also prefers her last name not be used, has been at her live-in job in Williamsburg for three years, and is happy with it. She gets overtime, sick days, and vacations, and she also gets respect. She has a good relationship with the mother of the child she takes care of. But that mother is not her friend; she is her boss. "Being a nanny is a job. It's difficult. It's not like you can sit at an office and take a lunch break.This is tough."

Proposed Changes In Welfare Reform

The federal welfare reform law of 1996 quietly expired on September 30, 2002, and has been repeatedly extended, most recently on September 30, 2003, for six months more. Major changes to the nation's public assistance system have been on the table for over a year, but little attention is being paid to them. The Senate version of a reauthorization bill is still in the Finance Committee; the House of Representatives' bill was passed last February.

If there was no violence in the Middle East, the proposed changes in welfare reform would still not headline the evening news. They are too technical for sound bites. Highlights include an increase in the required participation rate of beneficiaries, longer weekly hours in direct work activities, changes in the types of activities that count as work, and the possibility of "superwaivers."

HIGHER PARTICIPATION RATES CALL FOR MORE AVAILABLE JOBS

Currently, New York State must have half of its welfare caseload engaged in work activities, minus a varying percentage based on how many households have left the welfare rolls since 1995. Both the House and the Senate are proposing to increase that to 70 percent of the caseload by 2008.

Meanwhile, the national unemployment rate for women heading single-parent families

was 8.4 percent in August 2003, according to the Census Bureau. This was up more than a third since March 2001, and is much higher than the unemployment rate for women in general, which was 5.2 percent in August.

If the 70 percent participation rate were in effect today, New York City would need to get more than 16,000 welfare recipients into work activities. In the absence of new private sector jobs, the city would have to create subsidized or public-sector jobs. These would divert funds from services welfare recipients need to prepare for real jobs, such as child care, education, substance abuse treatment.

LONGER WORK WEEKS INCREASE THE NEED FOR CHILD CARE

The two major welfare reauthorization proposals put forth by the U.S. Congress provide an increase in child care funding of $200 million a year, according to the analysis released in September 2003 by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, and the Center for Law and Social Policy. This represents a seven percent increase over the current level. However, this past year, the New York state and city government both proposed measures that would have reduced available child care. While advocates succeeded in maintaining funds for pre-kindergarten and other child care options this year, the expected future budget gaps threaten to cancel out federal gains with state and local cuts.

The bill under consideration in the Senate Finance Committee would increase the required workweek for single parents receiving welfare by four hours each week, to a total of 24 weekly hours for those with children under the age of six, and 34 hours for other parents. The bill passed by the House in February would double the need for child care for children under age six by single-parent households on welfare, by increasing the mandatory workweek from 20 to 40 hours. It would increase the amount of child care needed for older children by 33 percent, as their parents' workweek lengthened from 30 to 40 hours.

DEAD-END JOBS FAVORED OVER TRAINING AND EDUCATION

Current welfare rules allow recipients to go to school for a year as their "work activity." After that, students must do 20 hours of other "core" work activities on top of their coursework in order to receive benefits. Both the House and Senate proposals would start adding work activities after three months of school, while increasing the number of hours required each week to 24. The Senate Finance Committee bill is slightly more lenient, allowing education to count toward some of the required 24 hours per week for an extra three months of every two-year period.

The City University of New York's institutional data show that in the first three years of welfare reform, about two-thirds of its students who received public assistance dropped out. There is no data on how many students stayed in school and lost public assistance benefits.

SUPERWAIVERS WOULD GIVE ALBANY CONTROL OF THE CITY'S WELFARE RULES

Superwaivers are the wild cards in the reauthorization debate. The House bill would allow states to apply for waivers of almost every rule and law governing public benefits, including welfare payments, housing, food stamps, homeless services, child care, employment training, literacy services, and any service funded under the Social Services Block Grant. The Senate Finance bill would limit superwaivers to ten states, who could be granted permission to waive laws and rules governing child care, welfare payments, and the Social Services Block Grant.

The process of welfare reform is getting little public scrutiny in the national arena; it will get even less in Albany. The state would be free to design a program meeting the needs of government officials to trim social service budgets to fund items more popular upstate.

UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS UNDER DISPUTE

In August 2001, after years during which trends in the city's welfare rolls closely matched those in the unemployment rate, the picture changed. Since then, unemployment has risen while the welfare rolls continue to drop. Either New York City has been experiencing a boom in the underground economy, with rapid expansion of unreported jobs, or a growing number of city residents are getting neither a paycheck nor a welfare check. The alternatives are to receive unemployment benefits, use up savings, live off somebody else's income, run up credit card bills and other debt, or turn to crime. Personal bankruptcies in the state are up 10 percent over last year. The increase in homelessness and bank robberies suggests that those two outcomes are also more prevalent.

Former welfare recipients, like other workers, are not eligible for unemployment benefits if they have worked for less than six months over a recent 12-month period, or if they never earned a salary of at least $1,600 a month. Once they lose jobs, 58 percent of New Yorkers remain unemployed long enough to run out of benefits, compared to 42 percent nationwide.

Even if workers are eligible for unemployment benefits, they may not be able to receive them. According to reporter Bob Port of the New York Daily News, a federal judge recently ruled that the state did not give fair hearings to about a third of the 47,000 New Yorkers appealing denials of their claims for unemployment benefits. If they had been granted benefits, the state's unemployment insurance fund would have been stretched even farther. As it was, in December 2002, the fund ran dry and began borrowing from the United States Treasury.

LOSS OF PRIVACY CAN BE THE PRICE OF RECEIVING SOCIAL SERVICES

Many Americans fear the loss of their privacy as electronic data banks and national security networks make personal information easier to obtain through both legal and illegal means. For clients receiving social services, like foster care and public assistance, this is old news. Between May and October, three journalists from two major New York City daily papers found confidential case records in the trash outside of several welfare offices, the city's child welfare agency, and the largest private children's service agency in the state. No high-tech expertise was required to gather information; the files were all on paper. They included photocopies or original copies of birth certificates, driver's licenses, income tax returns, child abuse reports, adoption records, and other sources of clients' names, addresses and Social Security numbers.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits.

The Marketing Of Culture

In the past few months, New York City Ballet's new workout video made the number-one spot on Amazon.com, and they have followed it up with a second "Ballerina Barbie" movie. While such deals are sure to draw sighs from dance aficionados, they may also be the new reality. Public funding for ballet and other cultural activities has dropped off, and many nonprofits can no longer afford to hold themselves aloof from the marketplace.

Cultural groups now have to work extra hard to keep audiences coming back. Subscriptions to dance or theater seasons and memberships to museums have not returned to pre-9/11 numbers, and many speculate that they never will. Whether audiences are too busy or too broke, they are no longer making long-term commitments to the arts. This means that cultural groups need to work harder to make a lasting impression -- to be sure that, if people enjoy one event, they will come back for more.

"Nonprofits are very open to change now," says D. K. Holland, a communications consultant that works with nonprofits, primarily on developing brand strategy. "Because of the funding situation, and the increased competition for time and attention, leaders of nonprofits are starting to realize that branding is extremely important."

Many arts groups are taking various steps to establish their "niche," and market their "product."

Promoting The Brand

Over the past decade, the lines between for-profit and nonprofit sectors have been blurring. Museums, theaters, and art galleries have increasingly turned to money-making enterprises, such as retail stores, cafe©s, and rentals.

Many nonprofits have become entrepreneurial in their approach to corporate sponsorship as well. With businesses becoming choosier about what they fund, arts groups are offering tailored opportunities for corporations to reach coveted markets: the young and hip, the well-heeled and leisure-minded.

General Motors' recent donation of $10 million to the "America on the Move" exhibit at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, the largest single donation ever made to a cultural group, won the car company naming rights, and a prominent place in all promotions. But while museum curators insist that the car company has had no influence on content, there have been accusations that the exhibit is a commercial for GM. The Guggenheim's Armani exhibit drew similar criticism.

Clarifying the Message

In the marketplace, the worst thing to do is to imply that your product is a generic, and thus replaceable, commodity.

Branding helps to distinguish one product from another, and is just as important if you're marketing shampoo, a political candidate, or the latest opera. Amid the many different entertainment options, arts groups are struggling to communicate who they are, and what they are offering.

The New York Times reported last month that the one-year-old Museum of Sex has had trouble attracting visitors even though its subject should, theoretically, sell itself. But most of the press coverage has been superficial because the museum has failed to communicate its mission-- to present the history, evolution, and cultural significance of human sexuality through exhibits on prostitution, erotica, burlesque, sexual freedom, and other topics.

Importance of Design

With higher standards of design permeating every aspect of culture (toasters, cars, even La-Z-Boy recliners), arts groups are producing higher-quality publicity and marketing materials. Many graphic designers work pro bono or at reduced rates for cultural groups.

That image is important is clear at place like the Brooklyn Academy of Music, which was branded under Harvey Lichtenstein as BAM. With the rechristening of the institution, the venerable institution set aside the baggage of the past (and confusion over its mission). BAM's simple, graphical logo and typeface; color-washed photography; trademarking (the Next Wave Festival; BAMcafe; BAMcinatek; even the BAMbus); and sleek website create a coherent sense of the organization's modern, forward-looking ambition. BAM adds " value" to its brand by offering seminars, discussions, and special events that deepen its audiences' ties to the organization.

Niche Marketing

With the graying of audiences for culture, producers have been working to cultivate the next generation of patrons. Like niche marketers, many producers seek out "early adopters" individuals who are already tuned in to their work, or willing to take risks and rely on them to spread the word.

Gen Art, an organization that showcases the work of up-and-coming filmmakers, fashion designers, DJs, and visual artists, has built a business out of niche marketing. The company was founded 10 years ago by two young people who noticed that their artist-friends were having trouble getting noticed by their peers. By cultivating contacts with friends and acquaintances, Gen Art has built a list of more than 100,000 people who want to hear about cultural events in their cities, New York, Los Angeles, Miami, San Francisco, and Chicago. Corporations sponsor screenings, gallery openings, and music events for the privilege of tapping into this young, hip demographic.

"You have to know where you are in your life cycle," Gen Art president, Adam Walden, says of this kind of niche marketing. "We started in the early '90s by putting up signs for events in SoHo and Chelsea. Putting up posters wouldn't make sense for us now; we're focusing on getting to the press and promoting what we do to the right people. We want to grow organically, and keep the core audience happy."

Limits of Branding

In theory, effective branding can help arts groups to communicate with audiences and generate sustainable sources of financial support. But going too far with corporate-style marketing risks backlash. Many people are drawn to culture because it seems to be at least one degree removed from the marketplace. Those who consider themselves outside a demographic box will be turned off by too-blunt tactics. Corporate partnerships such as the one between the Smithsonian and GM will be scrutinized closely by public and private funders as well as audiences. And, in the current financial climate, arts groups will continue to look for that elusive balance between the commercial and the creative sides of art.

Martha Hostetter has written about the arts for the Village Voice, American Theater and Empire New York.

Parents Last? Also: The Lower East Side, Poor But Not Broken

It is surely too soon to judge the advantages for children as a result of Children First, the education reforms introduced this school year, but a report released this month makes a case that the reform agenda is lacking in its efforts to bring parents into the decision-making process, denying parents a basic human right.

"Civil Society and School Accountability: A Human Rights Approach to Parent and Community Participation in NYC Schools," authored by the Center for Economic and Social Rights and New York University Institute for Education and Social Policy, suggests that Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Schools Chancellor Joel Klein need to align the Children First plan with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to include greater parent and community access, participation and monitoring.

Parental involvement is written into the Children First agenda, frequently with similar wording to what appears in the rights-based report--a welcoming atmosphere for parents, essential partnership, accountability--and according to Mayor Bloomberg, the Children First initiatives "recognize that parents must be full partners with our schools in the important work of education."

But in most endeavors, full partners make decisions.

" These reforms fail to guarantee parents their human right to have an impact on decisions that affects their child's education and to have access to school officials and to information," said Elizabeth Sullivan, Right to Education project coordinator at the Center for Economic and Social Rights (CESR).

" The process by which the Children First reforms were developed is a perfect example of this," said Sullivan. "There were countless forums held where parents could give 'input' into what policies might be adopted, but actual policy decisions and changes came as surprises with little or no time to comment on them."

Diane Lowman's 14-year old son, Sivaad, is just entering ninth grade at Pablo Neruda Academy in the Bronx. In the process of finding this school for Sivaad and getting him registered, Lowman made several trips to the district Learning Center where she said she was met with disregard and misinformation.

" I'm trying to be patient," said Lowman, "but I don't see that much different with Children First. It's like everything else with the Board of Ed. It exists on paper, but there's no substance to it; it's not real."

What would constitute real reform in Lowman's mind? "First of all, when I contacted the supervisor back in April about finding a school for my son, schools should have been identified that I could look at and visit while they were up and running. The parent coordinator should truly be knowledgeable and know what regulations are, be a true resource, not simply say, 'I don't know.' And someone should have asked parents what it is we need. Who do we hold accountable?"

Lowman admits that she is a pushy parent who knows her rights and will always manage to be heard. But other parents, perhaps those for whom English is a second language, may not be equipped to put up such a fight, and could easily find themselves disenfranchised from their child's education.

The ability of the new Parent Coordinator to bridge this information gap and truly be a support to parents is also under question by rights advocates. "If the Parent Coordinators are there to support parents," said Sullivan of CESR, "they need the training and knowledge to help parents address their concerns and the independence to advocate for parents before school officials. What parents need are individuals or structures that can serve as independent ombudspersons to monitor schools and school officials and serve as outside independent advocates for the human rights of parents and students."

Children should come first and it is for that reason that Diane Lowman struggles to stay involved. "We value education in my family," said Lowman, "but my son, he is now feeling it's not important. Parental involvement might change that. Parents need to know what is expected of our children. We need to stop sending our kids to school alone."

SCHOOL BUS POLLUTION HEARING

State Senator Peter M. Rivera led a joint hearing by the New York State Assembly Committees on Environmental Conservation, Education, Transportation, and the New York State Assembly Puerto Rican/Hispanic Task Force last month to hear testimony on "School Bus Pollution and its Impact on Children."

Studies (pdf format) have found high levels of diesel exhaust present on school buses. The fine particulate matter in diesel fumes has been linked to cancer and is a trigger for asthma, which is on the rise among New York City children.

Significant reductions in diesel exhaust can made by bus companies with a switch to ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel and retrofitting school buses with particulate filters or oxidation catalysts.

A COMMUNITY LIFELINE

In a recent Citizens Committee for Children Millennium Report, the Lower East Side was listed as the poorest neighborhood in New York City, poorer than areas in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens. But an unexpected finding was that the children from this community were not faring at the low end by all standard measurements of child well-being: immunization rates, infant deaths, low birth weights, teen pregnancies, high school drop-out rates, etc. The explanation for this twist has been attributed to the abundance of social service programs provided to families on the Lower East Side. One of the oldest and all-encompassing providers of these services has been the Educational Alliance, a settlement house established over 114 years ago and still vital to the community.

After September 11th, the Educational Alliance stayed open; during the blackout, it also remained open, making hamburgers on the street and passing out milk and apples.

Elisa Izquierdo, the six-year old girl murdered by her mother in 1995, lived in the housing project right behind Educational Alliance. "After she was killed," said the alliance's executive director, Robin Bernstein, "families and residents all came into the office of the Senior Associate Director and threw money down on the table--one man took a token off a chain around his neck and put it down--and they said, 'Will you buy this girl a funeral.' That's how the community looks to us."

Educational Alliance staff also realized from that tragedy that there was no safety net in place for parents who thought they might hurt their children and so they created a respite center where parents could drop in and talk about what was going on.

There are a wide range of other programs for children, from Head Start to After School. Day care parents pay between $3 and $35 a week, and for some families, even $3 is hard to part with; many of the parents work in sweatshops, an industry severely affected by 9/11. Recently Educational Alliance started the second year of their Saturday program and 245 children were waiting at 8:45 in the morning to register. There are also many social service programs, for pregnant teens and runaway kids and other troubled youth.

When Early Head Start research revealed that father involvement was one of the two most important variables in a child's life (exposure to violent incidents was the other), Educational Alliance began a father involvement program.

Lynda Crawford wrote the social services topic page for Gotham Gazette, and has written for City Limits, New York Woman, The New York Observer, and The New York Daily News.

The Gap Between Food Stamp Eligibility and Food Stamp Use

After the blackout of August 2003, health officials urged people to avoid eating spoiled food, issuing an advisory with the slogan, “If in doubt, throw it out.” People who could not afford to replace discarded food faced a difficult choice: go hungry or risk getting sick.

The federal food stamp program allows recipients to apply for replacement benefits after emergencies such as long power outages, and offers one-time emergency assistance to low-income people who do not qualify for food stamps. But this was not announced until August 18, four days after the blackout had begun. The city’s health department reported an increase in emergency room visits due to diarrhea on August 16.

To get replacement food stamp benefits, recipients had to report their food loss to the city’s Human Resource Administration by August 27, and fill out a two-page form to be received by the administration by September 8. Forms were available from the agency’s 40-plus job centers, as well as from some community-based organizations.

People who were not receiving food stamps, but had income below twice the poverty level, could get a cash payment to replace spoiled food. They had to go to a food stamp office by August 27 with proof of their income, family size, and residence in New York City. They were also required to return a completed application form to the Human Resources Administration by September 8.

Other Areas Affected by the Blackout Made It Easier to Apply for Food Assistance

Some counties in Michigan and New Jersey obtained permission from the federal government to simplify the process of getting food stamp replacements to people affected by the August 14 blackout. These counties automatically issued replacement benefits—about half of a month’s food stamp allotment—to all food stamp recipients, avoiding the need for individuals to apply for replacement benefits. According to Vicky Robinson of the United States Department of Agriculture, New York City and State did not request such permission. Connecticut allowed people to leave a telephone message for welfare workers instead of going into the office to report their loss. In Ohio’s Cuyahoga County, welfare offices were open late to allow people to submit applications after working hours.

There were 877,868 New York City residents receiving food stamp benefits in July 2003, a rise of seven percent over the previous July. By September 22, the Human Resource Administration estimated that it had processed 92,000 applications for replacement food stamp benefits, all of which were approved, resulting in grants of about $12 million. Additional applications were still being processed at that point.

In at least one instance, the Administration actively sought help from nonprofit organizations in reaching people who were not applying for food replacement assistance. Asian Americans for Equality was contacted by a Chinatown food stamp office on August 23, three days before the deadline for notifying the city about loss of food purchased with food stamp benefits, because few Asians had applied for replacement benefits. The organization told Asian community newspapers about this, and the newspapers ran a story the following day, bringing hundreds of applicants to Asian Americans for Equality’s offices that morning. The agency helped 4,000 food stamp recipients to fill out and submit applications by August 27.

Public Awareness of Food Assistance Options Is Low

The post-blackout food stamp replacement experience is an extreme example of the gap between resources available to those in need and their ability to learn whether and how they can receive them. Between August 13 and August 22, the Food Bank for New York City surveyed local adults about their need for food assistance. The survey found that the majority of city residents do not know they can get free food from Food Bank’s 1,100 neighborhood soup kitchens and food pantries.

Nationwide, the majority of clients of soup kitchens who report incomes low enough to qualify for food stamps are not getting them, often because they don’t know they are eligible. For the same reason, nearly half of the eligible families who are soup kitchen clients do not receive food benefits especially meant for babies, young children and their mothers; and children in one in five such families do not receive free school lunch. In New York City, all children are now offered free breakfast on school days.

Refunds May Be Returned to Recipients Paying Back Food Stamp Debts

Once a person begins to receive food stamp assistance, he or she is responsible for returning extra benefits paid out by mistake, regardless of whether the mistake was caused by fraud on the part of the recipient, by an inadvertent error in the recipient’s claim statement, or by government error. Since 1996, federal law requires states to take strong action to get back food stamp overpayments. New York State stopped this process in 2000, because of a class action suit on behalf of food stamp recipients that was filed by the New York Legal Assistance Group and the Greater Upstate Law Project.

The legal advocates acknowledged the state’s right to intercept income tax refunds to pay off food stamp debts, but argued that New York had done so improperly. The lawsuit claimed that people were not adequately notified that their refunds would be taken, and not given a chance to appeal the decision to do so. The lawyers also argued that there were errors in deciding whether people actually received overpayments, and that some overpayments happened so long ago that they no longer must be repaid.

On September 5, 2003, the court accepted a settlement under which the state can resume taking back overpayments, but must follow new procedures. The 4,000 New Yorkers whose refunds were taken will either receive checks automatically for the seized refunds, or will be notified that they can argue their case at a fair hearing. The average refund seized was about $550.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits. She is currently on the staff of Bronx Independent Living Services.

Flaws In The Screening Process For Foster Parents

The last of the children have departed. The house is empty. And you realize as you sit half listening to the television news that the years of changing diapers, wiping runny noses, and attending school field trips weren't all that bad. You liked being a parent. And you've come to realize that you have room in your heart and home for more children.

That is the story of most foster parents, according to Nicki McNeil of New Alternatives for Children, one of 42 agencies with whom the city contracts for foster care.

"Parenting is something they feel they do well and that they love to do," McNeil says. "They want the satisfaction of watching a child grow up."

But this is not the picture being painted by critics of the foster care system, who point to the latest tragedy as proof, the death of eight-year-old Stephanie Ramos. Stephanie was found dead earlier this month in a garbage truck. Police say her foster mother, Renee Johnson, placed Stephanie's 28-pound body in a garbage bag. As the Times reported, Johnson "has told the police that she panicked when the girl died. She is being held on charges of unlawfully disposing of a body and tampering with evidence. Law enforcement officials have said her home was filthy - covered with vermin and fecal matter - and are investigating whether neglect played a role in the child's death."

The question critics are asking is: How did this person become a foster parent?

THE SCREENING PROCESS

Becoming a foster parent does not look easy. One must be certified. The applicant must provide a medical report, income tax return, and three personal references. He or she must also be fingerprinted, undergo a criminal background check, and participate in a 10 week parenting training program, MAPP (Model Approach to Partnerships in Parenting).

Each person must also be assessed for personal motivations and life style, as well as the overall living conditions, during a "home study" which, says the Administration for Children Services, can take up to several months.

For all that, though, "it is an inherently flawed system of substitute care," charges Hank Orenstein, the director of the Child Welfare Project within the Office of Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum. The flaws, critics say, can be found in key areas of the screening process.

IN IT FOR THE MONEY?

Shortly after it was established in 1996, the Administration for Children's Services quickly set out to overhaul the child welfare system, focusing on what the agency calls neighborhood-based services. "Our aim is to place children close to home, so they can maintain social, cultural, identity ties, attend the same school, go to the same doctor," says agency spokesperson Mcclean Guthrie.

Designed to remedy one challenge, the shift to neighborhood placement may have created yet another.

Since many of the children who come into foster care are from low income areas, the agency began looking for foster parents who were from the same areas. And people from low incomes are more likely to be attracted by the stipend and other funds provide to cover the child's expenses.

To weed out those who might be in it for the money, the agency requires proof that a potential foster parent's income, whether from work or public assistance, at least covers their own expenses.

IS THE WHOLE HOUSEHOLD SCREENED?

When conducting the home study, the agencies aren't just interested in the home itself which must meet basic physical and safety requirements, but the hearts and minds of its inhabitants.

"A good foster care agency should screen for genuine, caring, and empathetic foster parents, and should get to know them as human beings," says Orenstein. And that means everybody in the home.

"Everyone is interviewed separately," says McNeil. And all family members living in the home who are over the age of 18 including the potential foster parents must be fingerprinted and processed through the State Central Register for Child Abuse and Maltreatment (SCR).

As for those under the age of 18, "they don't look closely at minor children in the home," says Orenstein. The law prohibits anyone from conducting a criminal background check on a minor.

THE SCREENERS

The screening process is only as good as the person who does the screening, and the caseload of caseworkers in New York City is well above the national average, which may explain why there is a 40 percent turnover in caseworkers.

PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTING?

Being a foster parent, like being social worker, is quite stressful.

"They might be relatively stable today, but a month from now, they might have some crisis," says Orenstein.

McNeil agrees. "Many are working full time. They may have someone who dies. They have to deal with their own grief while dealing with the child."

Sound psychological testing can help to determine who is mentally and emotionally fit to care for a foster child in both good times and bad.

One agency, New Alternatives for Children, which places children with severe medical and physical disabilities, requires that potential foster parents undergo psychological testing.

"Every prospective foster parent meets with our psychiatrist. It helps us help parents decide if this is for them. It helps us rule out possibilities of problems down the road," says Dr. Arlene Goldsmith, executive director of New Alternatives.

It is not certain whether Renee Johnson underwent psychological testing.

Though foster care agency executives like McNeil believe that most foster parents are "good hearted people who want to care for children," critics like Orenstein see a system that removes children from their parents for neglect, and places them "in a situation that's not any better.

"When a child dies it's a lightning rod, says Orenstein. "Tragically, some children die. But there are a lot of others that are not having a healthy or happy time. "

Carla Thompson is a Brooklyn-based journalist.

Welfare Reform

Nicole Thomas, a 29-year-old mother of two, has been on and off welfare for years. With a tenth-grade

education and a resume that includes jobs in fast food and retail, she knew she needed more education to find the kind of steady job that would enable her to support herself and her family. But when Thomas told city welfare officials she wanted to fulfill

her mandatory 35-hour per week work requirement by attending a GED (high school equivalency) program, they informed her she could attend classes only two days a week, and had to spend the other three days working as a receptionist at a nursing home.

Frustrated that the city's inflexibility would more than double the time she needed to get her GED, Thomas left the welfare-to-work program and started an internship at Families United for Racial and Economic Equality ("FUREE"), a grass-roots organization

that supports increasing welfare recipients' access to training and education. While she worries this may jeopardize her welfare grant, she hopes to pass the high school equivalency examination soon and then find a job so she can leave welfare permanently.

Nicole Thomas, a 29-year-old mother of two, has been on and off welfare for years. With a tenth-grade

education and a resume that includes jobs in fast food and retail, she knew she needed more education to find the kind of steady job that would enable her to support herself and her family. But when Thomas told city welfare officials she wanted to fulfill

her mandatory 35-hour per week work requirement by attending a GED (high school equivalency) program, they informed her she could attend classes only two days a week, and had to spend the other three days working as a receptionist at a nursing home.

Frustrated that the city's inflexibility would more than double the time she needed to get her GED, Thomas left the welfare-to-work program and started an internship at Families United for Racial and Economic Equality ("FUREE"), a grass-roots organization

that supports increasing welfare recipients' access to training and education. While she worries this may jeopardize her welfare grant, she hopes to pass the high school equivalency examination soon and then find a job so she can leave welfare permanently.

The lives of people like Nicole Thomas were supposed to get easier, not harder under Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Unlike his predecessor, Mayor Bloomberg seemed to understand the importance of addressing barriers to employment rather than single-mindedly trying to reduce the welfare rolls. Advocates talked optimistically about the mayor's more open-minded approach to welfare reform.

But the Bloomberg administration has since reversed course, taking aim at programs to increase welfare recipients' access to education, training, and permanent jobs. That the mayor has done so through litigation is particularly ironic in light of his frequent criticisms of advocates for pressing their claims through the courts.

Last year, the mayor sued over a transitional jobs program law that would have required the city to create 2,500 jobs for welfare recipients at government agencies and not-for-profit organizations for one year to help them make the transition to permanent employment. The suit did not attack the program's merits, but claimed it was "preempted" by existing state legislation granting authority over jobs programs to the city's top social services official, a Bloomberg appointee. In May, a state court judge ruled in the mayor's favor and invalidated the law.

The mayor recently returned to court to challenge the Coalition for Access to Training and Education law, also known as CATE, passed by the city council in April over his veto. This law represents the culmination of efforts to create a viable alternative to dead-end workfare assignments. It allows welfare recipients to satisfy welfare work requirements, which can reach up to 35 hours per week, by engaging in education or training activities, including college classes, GED programs, vocational training, adult literacy, and ESL courses. Previously, participation in these activities remained within the discretion of city welfare officials, who often resisted any alternatives to typical job search and workfare assignments. The mayor's legal complaint does not challenge the basic assumptions behind the law but rather boils down to a turf dispute with city council over who should determine welfare policy.

Experts widely agree that education and job training provide the best opportunity for people to leave welfare for lives of independence and self-sufficiency. Eighty-seven percent of welfare recipients in New York City who graduated from a four-year college stayed off welfare. While conservative policymakers tout the value of even the most menial labor, typical workfare assignments like sweeping streets and cleaning parks rarely lead to permanent employment in today's high-tech, service-oriented economy. In New York City, over 75 percent of employers require at least two years of college for any entry level job. Also, work requirements have previously served as a tool to cut people from the rolls for missed appointments or other forms of supposed non-compliance. While the rolls have dropped significantly in the city since the late 1990s, it is far from clear that welfare reform has actually reduced poverty. Education, along with employment skills and child care assistance, remain leading barriers to permanent employment. Of those remaining on welfare in New York City, over 50 percent lack a high school diploma or GED.

When Ramona Ledesma, who is originally from the Dominican Republic, applied for welfare she felt she understood better than anyone what had prevented her from finding a permanent job. But welfare officials immediately forced her to split her time between a workfare program and job-preparation classes. It never occurred to them, she recounted in her testimony before the city council, that the first step to prepare her for work was to enable her to learn English. To make matters worse, her case was closed twice due to administrative error, requiring her to start the process from the beginning each time.

In part, Mayor Bloomberg's rigid view of work requirements reflects a broader shift at the national level. Even before President Bill Clinton promised to "end welfare as we know it," the federal government had been seeking to reduce dependency by shifting the emphasis from welfare to work. A 1988 federal law imposed a comprehensive scheme of mandatory work requirements on welfare recipients, though the law also favored training and education programs over workfare. The real change came with the welfare reform act of 1996, formally entitled the "Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act." This act replaced the federal entitlement to cash assistance with a block grant to states and imposed a system of strict work requirements on recipients. While it permits states to choose whether college courses and other education programs can be applied towards an individual's work requirement, the act simultaneously prohibits states from counting those individuals in satisfying their mandatory overall state-wide participation rates.

Federal law still allows for innovative programs like the city's access to education and training law because at most 50 percent of the total welfare recipients in a social service district must currently participate in a work program -- and less if, as in New York, a state has earned credit for reducing its overall caseload by a specified level. Still, as a result of changes in federal law and the city's response, the number of welfare recipients in college has declined from over 25,000 in 1995 to under 5,000 today.

Despite the new jargon about "personal responsibility," trying to solve poverty by making poor people work is hardly innovative. Under the poor laws of seventeenth century England, assistance was limited to the "deserving" poor, a category consisting mainly of the old and infirm. Able-bodied indigents who refused to work could be convicted of vagrancy, confined to a workhouse, or publicly whipped. This moralistic and punitive view of poverty helped shape the development of welfare in America. According to Mimi Abramovitz, a professor at the Hunter College School of Social Work and expert on social welfare policy, opposing measures like the access to training and education law, "punishes single mothers for being single mothers." Although today's "work first" initiative portrays itself as inculcating welfare recipients with a good work ethic, it fails to provide the corresponding skills, education, and access to permanent jobs they need to succeed.

Then there is the old unwritten rule that those receiving public assistance must remain worse off than those with jobs. If welfare benefits were competitive even with minimum-wage salaries, so the argument goes, people would lose their incentive to work. By extension, single mothers would be getting an unfair advantage over the working poor if they received a free government handout while taking college courses or learning English as a second language.

Making welfare recipients work rather than improving their access to training and education has a further advantage, at least to the private sector. "By increasing the competition for unskilled, low-wage jobs, work requirements help keep wages down and labor costs low," says Abramovitz.

Mayor Bloomberg, who ordinarily opts for pragmatism over ideology, has recently adopted conservative slogans about the uplifting value of work that bear little relation to the hard evidence about workfare programs. A recent report by the Brookings Institution observes that only nine percent of those who enrolled in New York City's main workfare program found unsubsidized employment.

The mayor has expressed concern that local training and education laws could place the city in jeopardy of losing federal welfare dollars if work requirements are tightened when Congress takes up reauthorization of the 1996 act later this year. Yet the access to education and training law itself explicitly avoids that problem by requiring that participation rates remain within existing mandates. Nor does the city's current fiscal crisis justify the mayor's opposition towards the transitional jobs program, which was overwhelmingly funded by the federal and state government, with the city contributing only $4 million of the total estimated $50 million cost.

While work requirements have become a permanent part of the American welfare system, true reform will rely not on slogans but on innovative policies that address the real obstacles to permanent employment confronting welfare recipients.

Jonathan Hafetz is a public interest lawyer formerly with the Partnership for the Homeless

The Mayor's Plan To "Streamline" Social Services

In the relief at Mayor Michael Bloomberg's decision to restore some of the cuts he originally proposed to social services, the spotlight has shifted off proposals that may influence the field long after next year's budget is forgotten.

In his Executive Budget, the mayor proposed to "streamline" city social services by moving a number of programs from one agency to another. The best publicized proposal involved reorganizing AIDS services, by folding the Mayor's Office for AIDS Policy into the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and contracting out case management services now done by the HIV/AIDS Services Administration. After well-organized opposition and civil disobedience, advocates have approached the City Council about making the AIDS office a permanent unit of city government.

But there are many other units and services that will still move from one agency to another under the plan. This restructuring is meant to save money, but its potential effects on city spending -- as well as on clients and the local economy -- are unpredictable. Since in New York City, only one percent of the social service workforce is on the government payroll, it is the nonprofit social service agencies -- which get nearly two-thirds of their revenue from government grants and contracts -- that are most worried about the restructuring.

"I don't get the feeling that the city has put a lot of thought into the restructuring," says City Project's Bonnie Brower.

EMPLOYMENT SERVICES

Under the mayor's plan, the Department of Employment would be eliminated, and its services transferred to the Human Resources Administration. Public services are shaped by the agencies that control them. When job training comes out of a welfare agency, it is managed by a staff used to making clients prove that they deserve public benefits. This is not the mindset needed to encourage unemployed and underemployed New Yorkers at every level of income and education to use job-related services-the mandated use of funding from the federal Workforce Investment Act, which pays for most job training contracts.

The one exception to this shift is the Summer Youth Employment Program, which would go to the Department of Youth and Community Development. Providers of summer youth employment services may prefer dealing with the youth agency to waiting out the Department of Employment's delays: 96 percent of that agency's contracts were registered late in 2002.There is a possibility that the city will decide to move adult employment services to the Department of Business Services instead, which would demonstrate recognition that a well-prepared workforce is an economic asset. However, the Department of Business Services managed only $25 million worth of contracts last year, and may not have the capacity to abruptly add at least four times that amount to its responsibilities.

HUMAN RESOURCES ADMINISTRATION

The Human Resources Administration would take over many tasks currently performed by other agencies. For example, it would take over substance abuse services from the Department of Health and Mental Health; would take over child support enforcement from the Administration for Children's Services; and would take over the tasks of determining who is eligible for subsidized day care services, assistance with heating bills, and a home care program.

The restructuring plan would thus give the Human Resources Administration control over who receives several services that are not targeted to welfare recipients.

THE ELDERLY

The 105 senior centers that are located in New York City Housing Authority projects, about one-fourth of those citywide, would become programs of the Housing Authority, rather than of the Department for the Aging.

Instead of dealing with the Department for the Aging, elderly people in need of home care and the Home Energy Assistance Program would deal with welfare workers, as would low-income working parents seeking affordable day care.

AFTER-SCHOOL PROGRAMS

After-school programs would be transferred to the Department of Youth and Community Development, from both the Administration for Children's Services and the Department of Education. If after-school programs move from the Administration for Children's Services, with only 61 percent of its contracts registered late in 2002, to the Department of Youth and Community Development, with 86 percent of its contracts registered late that year, they may face longer delays.

The Department of Youth and Community Development would have to manage a sharp increase in its volume of contracts, a prospect advocates find unsettling. The logistics of the after-school contract transfer are not clear: many providers have one contract covering both pre-school children -- whose care would remain under the Administration for Children's Services -- and school-age children, whose care would shift to the youth agency. "Now they're going to rip out the school-age part of it, and we're not being told how," says Susan Stamler, of United Neighborhood Houses, whose settlement house members run a variety of human services. "It's wreaking havoc among providers."

Stamler's agency has recommended that the city maintain the quality and comprehensiveness of any after-school programs transferred, and develop an orderly process before any transition begins. "We're extremely concerned about avoiding disruptions during the school year."

Irma Rodriguez of Forest Hills Community House points out that the two agencies operate differently. "DYCD programs are typically based on a calendar year. ACS is based on the parents' year. They [ACS] understand the dynamics of working parents and their schedules."

Amid all the technicalities, the human dimension of contracted services can be forgotten. Susan Stamler brings the discussion back to the purpose of city-funded after-school programs: "Parents need to know their children are getting safe, reliable care that they can get to in their communities." Anything less will mean streamlining has gone too far.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits. She is currently on the staff of Bronx Independent Living Services.

Threatened Change To HIV/AIDS Services

The drug regimen that has changed AIDS from a death sentence to a chronic disease for many New Yorkers requires patients to follow a complicated daily routine, which they do at a far higher rate than patients with other diagnoses comply with their medical instructions. AIDS and HIV patients do what they are supposed to 70 percent of the time, while other patients do so only about half the time. Unfortunately, to be effective, HIV treatment regimens require 95 percent compliance, a level nearly impossible to maintain without a clear mind, stable housing, adequate food and cooking facilities, and consistent coverage for medical care and prescriptions.

That is why AIDS activists see social and support services as a crucial factor in the health of people with AIDS, and why they so bitterly criticize Mayor Michael Bloomberg for his proposals to change Local Law 49, which governs the city agency known as the HIV/AIDS Services Administration.

WHO USES THE CITY’S HIV/AIDS SUPPORT SERVICES?

The city’s HIV/AIDS Services Administration’s 31,000 primary caseload includes the majority of New Yorkers with AIDS, plus a small number of those with HIV infection only. Over 14,000 family members of people diagnosed with HIV/AIDS also receive certain HIV/AIDS Services Administration services: counseling on daily living skills, housing—if they live with the HIV-positive person —and if their relative dies, bereavement counseling and help in finding non-AIDS-related housing.

Not all people with AIDS need HIV/AIDS Services Administration’s help. With therapeutic drugs, some are able to continue working, maintaining insurance that covers their treatment, including medication. Others receive long-term disability payments through private insurance provided by former employers. However, all but the wealthiest people with AIDS face the possibility that they may eventually become too sick to work, and/or outlive their savings or other resources.

AIDS is most prevalent among people who are already poor, but it also makes middle-class people poor. It forces them to cut back on work or quit their jobs, pay extraordinarily high bills for prescription drugs—which are rarely completely covered by health insurance—and cope with unpredictable symptoms. The diagnosis alone creates emotional turmoil, sometimes requiring mental health treatment. Newly-diagnosed parents must decide whether or not to tell their children, who should care for the children if a parent dies, and how to juggle medical appointments, child care, and financial commitments.

A 1997 study by the national Centers for Disease Control found that people receiving care for HIV-related disease were twice as likely as others to be unemployed, to have household incomes below $25,000 per year, and to have either public insurance, such as Medicaid, or no health insurance at all. For low-income HIV-positive New Yorkers, government benefits (not necessarily health care) can be the most crucial life support system.

BLOOMBERG’S PROPOSALS TARGET HIV/AIDS OFFICE AND SERVICES

Mayor Bloomberg has announced his intention to seek unspecified changes in Local Law 49, so that the city can provide more help for women and more job training for clients wanting to return to work. However, changing the law could also remove legal limits to the number of clients per caseworker, and to how long the administration can take to deliver benefits. Opponents of this proposal believe that the mayor’s real goal is to weaken the law, so that his proposed budget actions would no longer violate it.

Under the mayor’s executive budget for Fiscal 2004, 29 HIV/AIDS Services Administration case manager positions would be eliminated, case management services for all clients would be privatized, and city funds for HIV-prevention services for communities of color would be eliminated, Under the more drastic “doomsday” scenario, each contractor providing supportive housing for people with HIV/AIDS would take a 10 percent funding cut, affecting 4,000 residents with HIV/AIDS. Also, the city would eliminate all government benefits case management, public and private, for people with HIV/AIDS.

AIDS activists are vigorously protesting these policies. “People are disappointed that we have to do the same thing we were doing with Giuliani,” said Terri Smith-Caronia of Housing Works, an AIDS service and advocacy organization. “At least Giuliani came out and said ‘I hate poor people, I hate the disabled.’ Bloomberg is far more disingenuous, more dangerous.”

The executive budget also proposes that the Mayor’s Office of AIDS Policy Coordination be folded into the health department.

“The implications are huge,” explained Smith-Caronia. “Having this office affirms to the world that this city has a commitment to develop a coordinated policy on AIDS. The Mayor’s Office is a hair’s breadth above all the other agencies that deal with AIDS, so it can make sure the city doesn’t waste federal dollars on duplicating services across departments.”

THE NEED FOR MORE COORDINATION IN THE HIV/AIDS SERVICE SYSTEM

In February 2003, the Center for an Urban Future released a critique of the New York City HIV/AIDS service system, in which author Julie Hantman detailed how the lack of coordinated, objective planning has produced a glut of some social support services and a shortage of others, with a disproportionate share of nonprofit services being located in Manhattan. Of the 250-odd nonprofit organizations providing one or more HIV/AIDS-related services, only 15 offer a full selection at a single site. The rest advocate for “one-stop shopping” for public benefits at the HIV/AIDS Services Administration, but are themselves fragments in a labyrinth of community-based social services. It is just as difficult for a person with nausea, fever, and dementia to travel between multiple nonprofit agencies for mental health care, case management, substance abuse treatment, and food pantry bundles, as it is for them to travel between HRA offices to coordinate welfare benefits, Medicaid, and food stamps.

The term “case management” can refer to coordination of different kinds of services. Medical case managers coordinate health care services. Case managers at community-based organizations coordinate services ranging from housing and food to substance abuse and mental health treatment. For consumers who are poor enough, the HIV/AIDS Services Administration’s staff performs government benefits case management, coordinating public assistance, Social Security Disability benefits, Supplemental Security Income, Medicaid, food stamps, and emergency food and housing assistance.

AIDS activists are critical of the city’s use of federal housing funds to pay the salaries of HIV/AIDS Services Administration employees. “This is $50 million that was meant to be used to build housing for people with AIDS,” says Jennifer Flynn of the New York City AIDS Housing Network. However, she does not support privatizing or eliminating HIV/AIDS Services Administration case management in order to free up federal funds for AIDS housing. According to Flynn, the administration’s case managers are unique, in that as city workers, they are authorized to decide whether applicants are eligible for government benefits and to issue checks, food stamp cards, and other concrete benefits.

“State law requires that it be a state or local district employee that decides eligibility,” she points out, noting that this function could not be performed by private agency employees, but would revert to regular welfare eligibility workers. Those workers lack expertise in AIDS issues, and carry far higher caseloads than the maximum of 34 allowed under Local Law 49 for HIV/AIDS Services Administration caseworkers.

THE MEDICAL IMPACT OF UNMET SOCIAL NEEDS