The Social Security Debate

You cannot go anywhere these days without hearing about Social Security. In the first two weeks of March, the New York Times ran more than 50 articles on it. President Bush barnstorms across the country promoting his ideas, while Democrats hold rallies to oppose them. People, such as New Yorker Beatrice Williams Rude, email their stories about Social Security to blogs. She told of her parents who, despite being knowledgeable investors, saw their savings dwindle in the 1980s. “But Social Security was there” and her parents “never stopped blessing FDR for Social Security: retirement with dignity.”

You cannot go anywhere these days without hearing about Social Security. In the first two weeks of March, the New York Times ran more than 50 articles on it. President Bush barnstorms across the country promoting his ideas, while Democrats hold rallies to oppose them. People, such as New Yorker Beatrice Williams Rude, email their stories about Social Security to blogs. She told of her parents who, despite being knowledgeable investors, saw their savings dwindle in the 1980s. “But Social Security was there” and her parents “never stopped blessing FDR for Social Security: retirement with dignity.”

And hundreds of New Yorkers – many of them decades from retirement – packed an auditorium at the New York Ethical Culture Society last week – to cheer, boo and whistle as experts debated the future of a program that, in one way or another, affects almost all Americans.

About 47 million Americans, including 673,000 New York City retirees, receive Social Security. Millions of New Yorkers and other Americans have Social Security taxes deducted from their paychecks and hope to collect benefits some day.

So it is not surprising that any effort to change the program would spark interest and strong emotions. To make the debate even more vehement, there is little common ground here. People disagree over what Social Security is – a pension fund or an insurance program to guarantee some degree of economic security for all. Americans argue over the proper role of government in insuring a decent retirement. They differ over the magnitude of the financial problems confronting Social Security. And they have bitter differences over the best approach to solving the problem – whatever the problem might be.

President Bush has declared Social Security to be in crisis and has made changing the system the focus of domestic policy in his second term. He has argued that the system will be “bankrupt” by 2042 and needs to be fixed “now once and for all.” Bush has pulled out all the stops in pushing for voluntary private accounts where people could put some of the money that goes into Social Security.

But -– and this indicates just how convoluted this whole debate has become -- even the White House admits private accounts will not solve Social Security’s financial problems.

Beyond the discussions of money, this is a political and ideological battle. Bush sees the private accounts as key to creating his “ownership society,” where patients control their health care, parents control their children's education, and workers control their retirement savings.

In a memo written earlier this year, Peter Wehner, a White House aide, called the debate about Social Security “a monumental clash of ideas.” “If we succeed in reforming Social Security, it will rank as one of the most significant conservative governing achievements ever,” he said, emphasizing, “we consider our Social Security reform not simply an economic challenge, but a moral goal and a moral good.”

Opponents see the Bush administration proposal as a dangerous effort to destroy the remaining vestiges of the New Deal and to weaken a program that has kept millions of senior citizens and others out of poverty.

“Our society has decided that everybody – the elderly, the disabled, orphans, and surviving spouses – is morally equal, and … deserves the peace of mind that is implied by the term â€social security,’” Dan Cantor of the New York Working Families Party wrote recently. “This is moral progress, and Bush is on the other side.”

Democrats and labor unions have launched an all-out attack on the private accounts. They have not, however, agreed on a proposal to solve whatever fiscal problems confront the system. Meanwhile, the public is left trying to sort it all out.

• HOW IT WORKS

• THE NEW YORK CONNECTION

• DEFINING THE PROBLEM

• PRIVATE ACCOUNTS

• THE SOLVENCY PROBLEM

• THE OTHER DEFICITS

• THE POLITICS

• A WALL STREET BOOM?

HOW IT WORKS

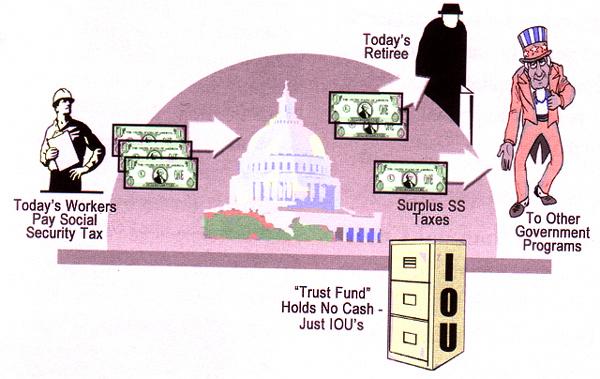

To finance Social Security, workers pay a tax of 6.2 percent on their earnings up to $90,0000. Their employers pay an equal amount. Though some people still think the money that workers pay in Social Security taxes today is squirreled away for them until they are ready to retire in the future, in fact the money collected today is spent today; it goes to make monthly payments to today’s beneficiaries. (Retirees of the future are supposed to be paid by Social Security taxes collected from workers of the future.) This is sometimes referred to as pay-as-you-go.

Most people receiving Social Security are retirees and their spouses, but benefits also go out to 7 million disabled workers and their dependents and 7 million survivors of deceased workers. In 2004, individual retirees received an average Social Security benefit of $922 a month, with married couples getting an average of $1,523.

Today's "Pay-As-You-Go" Social Security System

Illustration from Cato Institute's A Community Leader's Guide to Social Security Choice

For about two thirds of beneficiaries, Social Security provides at least 50 percent of their incomes. For about 20 percent, it accounts for virtually all their income. A new study by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities found that without Social Security, 44.4 percent of senior citizens in New York State would have incomes below the poverty line. With Social Security, the number drops to 8.4 percent, meaning that Social Security keeps almost 900,000 New Yorkers out of poverty.

The size of the monthly check depends upon how much money a person paid into the system, which, in turn, is based on how much the person earned and how long he or she worked.

A person who spent years at a high-paying job will get a larger check than someone who earned a low wage, but because the government intended that Social Security keep elderly and disabled people out of poverty, the less affluent get a higher rate of return on the money they put into Social Security than richer Americans. According to figures compiled by the Century Foundation, low-wage workers who retired at 65 in 2004 received Social Security checks equivalent to almost 85 percent of their wages; people who earned higher salaries saw only 45 percent of their wages replaced by Social Security.

And because the checks keep coming from retirement to death, people who live longer -- or whose spouses live longer -- do better with Social Security than those who die shortly after retiring. The government adjusts the benefits to keep pace with inflation.

Social Security operates through the federal budget, but the Social Security Trust Fund is a distinct entity. When there is a surplus –- when more money is coming in in payroll taxes than going out in benefits -– it is credited to the Social Security Trust Fund. The federal government borrows the money to pay for other programs and must then pay the Trust Fund back with interest. This year, for example, the money left over from Social Security reduced the current federal budget deficit by more than $170 billion. The federal debt held by the Trust Fund is currently about $1.8 trillion.

So even though Social Security’s revenue will fall short of benefits in 2018, Social Security can fill that gap with the money the federal government owes to the Trust Fund until 2042. It is then, when the Trust Fund is depleted, that the president says the Social Security system will be “bankrupt.”

THE NEW YORK CONNECTION

The idea for such a Social Security system came largely from three New Yorkers in the 1930s: President Franklin Roosevelt, Senator Robert Wagner, and Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, according to Maura Moynihan, daughter of the late New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Some 50 years later, Senator Moynihan, along with Republican Senator Robert Dole of Kansas, spearheaded the 1983 adjustments to Social Security that saved the system from imminent collapse by reducing some benefits, gradually increasing the retirement age from 65 to 67, hiking some taxes and delaying cost of living increases.

This year, Representative Charles Rangel of New York has emerged as a key opponent of the president’s plan because of his position as the senior Democrat on the House Ways and Means Committee, which will have to review any legislation on Social Security. And, when Democrats kicked off their offensive in the hottest domestic political fight of the year, they came to Pace University in New York City. New York Senator Hillary Clinton sponsored the rally where New York’s other senator, Charles Schumer, also spoke.

But not all New Yorkers agree with them. Some members of one of the city’s leading industries – the securities industry – hope the president’s plan for Social Security will pump more money into stocks and provide billions in fees for some investment firms.

DEFINING THE PROBLEM

To spur his proposed changes, the president has painted a frightening scenario for Social Security’s future. According to the White House, in 2018, the government will begin to pay out more in Social Security benefits than it collects in payroll taxes. Unless the government takes action, by 2027, the shortfall will reach $200 billion a year and, by 2042 –- when today’s 28-year-olds reach 65 -- the system will be bankrupt.

With birth rates down and the baby boom generation retiring, 21st century workers simply cannot keep up with the demand for benefits, the administration says. In 1950, each Social Security recipient was supported by the Social Security taxes collected from 16 workers. Today's Social Security recipient depends on only 3.3 workers.

“If we do not act to fix Social Security now, the only solutions will be dramatically higher taxes, massive new borrowing or sudden and severe cuts in Social Security benefits or other government programs,” the president has said.

But many of Bush’s critics dismiss such dire predictions. “The most successful safety net program in human history is currently sitting on $1.7 trillion in reserve funds and faces a possible shortfall decades from now, which minor corrections to the program could prevent,” wrote Robert Scheer in The Nation.

PRIVATE ACCOUNTS

The president has made private accounts the linchpin of his plan for Social Security.

Under this proposal, workers would eventually be able to take the 4 percent of their incomes that is subject to payroll taxes and put it in private accounts, instead of the Social Security. There might be a choice of funds, all run by professional money managers, that would put the money into some combination of stocks and bonds.

The plan would begin in 2009 with workers able to invest up to $1,000 in the private accounts. That would rise by about $100 a year until, after 26 years, it would reach its maximum –- $3,600 a year (in today’s dollars). Current retirees and workers aged 55 and over would not be affected.

Many details have yet to be determined, including how the funds would be managed, how many funds would be offered, and what if any the fees would be. The president’s plan does not set out a social safety net, though many of the bills proposed in Congress do. And it does not address how Social Security would handle benefits for people other than retirees -- for disabled workers or survivors of deceased workers.

The plan also presents daunting logistical challenges. “Any system that includes private accounts would require a massive effort to educate the public, enroll workers and answer what experts say could be hundreds of millions of questions,” Tom Lauricella wrote in the Wall Street Journal. “Computer systems to track contributions would have to be designed and built. Money would have to be collected and allocated. And the system would have to be policed for errors to ensure that workers get every penny they are due.”

For the next 45 to 55 years, private accounts could exacerbate Social Security’s fiscal problems. The money that working Americans put into private accounts will not be available to pay retirees’ benefits, since it will not go into the Trust Fund. That will require the government to borrow more money -- trillions some say -- to fill the gap.

Supporters of private accounts say that the government will have to spend huge amounts of money -- either in general funds or from government bonds -- on Social Security in any event. Paying the money to move to private accounts, argues the Heritage Foundation, would be more cost effective in the long run “than to continue to fund the system as it is currently designed.”

With private accounts, future Social Security benefit levels become unpredictable. The amount of money diverted to the private funds and the cost of borrowing money to fill the gap during the transition to personal accounts would reduce the size of the Trust Fund.

Then there is the biggest unknown: What return will people earn on their private accounts? Some have estimated that workers would have to get more than 3 percent (after inflation) to do better than they would do under the current system.

According to Paul Krugman, an economics professor at Princeton University and columnist for the New York Times, most privatization advocates assume over time a 7 percent return, after an inflation adjustment of 3 percent. In that case, retirees with private accounts would come out ahead.

Getting an account that makes financial sense is “not a slam dunk, but it ought to be attainable,” wrote Newsweek Wall Street editor Allan Sloan. But the accounts have other hitches, Sloan says. You would own them, but not control them (for example, you could not withdraw from them before retirement), and the money paid into these accounts would reduce the size of your conventional Social Security benefit.

|

Publications by an array of organizations stake out different sides in the heated debate over the future of Social Securit |

New York Senator Chuck Schumer has sought to dramatize the risk. His web site allows New Yorkers to compare their retirement benefits under the Bush plan with those under the current system (in inflation-adjusted 2005 dollars).

So, for example, a 40-year old with an average salary of $60,000 who would receive an annual benefit of $23,832 under the current system, and an annual benefit of $19,598 -- an 18 percent cut -- from the Bush plan. To make such calculations, Schumer assumes (In PDF Format) that the private accounts would get an annual return of 3 percent above inflation. A higher rate would produce additional benefits.

The debate over private accounts involves differing ideas of government’s proper role and of what Social Security is. Proponents of private accounts argue that individual Americans should have more control of their retirement funds and should be able to pass their unused retirement funds on to their heirs.

“Social Security turns us all into supplicants,” Michael Tanner of the Cato Institute said at the Ethical Culture Society debate. Private accounts, he said, would provide “a system in which middle and low income people can create a nest egg of real inheritable wealth....It’s about time we gave the doorman the same opportunity to invest as the person who lives in the duplex above.”

But that misses the purpose of Social Security, Krugman countered. “Social Security is not a pension fund, not an investment fund but a social insurance program,” he said

THE SOLVENCY PROBLEM

Whatever else private accounts may – or may not — do, they do not address Social Security’s fiscal health for much of the 21st century. "Personal accounts do not solve the issue," Bush said at his press conference last week.

A number of suggestions have been made about how to do that. They include:

--Limiting benefits for wealthy retirees: Currently a person’s overall wealth has nothing to do with the benefit he or she receives. Some people have suggested changing this, with the president indicating he would consider it.

--Other benefit cuts: Currently, Social Security benefits rise along with wages. Some experts have suggested that the increase instead be tied to rises in prices, which tend to go up more slowly than wages. This could reportedly take care of the solvency problem single-handedly but would also reduce benefits. According to calculations by Representative Anthony Weiner, this would gradually erode the size of benefit checks. The average 48-year-old New Yorker, who can now expect $940 a month, would get only $846. And younger workers would do worse: 18-year-old New Yorkers would see their benefits drop by a third – from an average of $940 to $640 a month.

--Increasing the retirement age: Senator Charles Hagel, an influential Republican and supporter of private accounts, has urged raising the retirement age from 67 to 68 in 2023, largely on the grounds that people live longer now than they did in the 1930s. Opponents of older retirement, such as the influential senior group AARP argue that such a move would disproportionately affect African-American workers, (in pdf format) who have lower life expectancies than whites. They also point out that just because people live longer does not mean they can work longer. Older workers may be unable to do physically demanding work and often face age discrimination that can prevent them from getting or keeping jobs.

--Raising the “wage cap”: Workers and employers only pay Social Security payroll taxes on the first $90,000 of earnings. This creates a maximum tax -- for the worker and employer -– of $5,580 a year. If the cap went up to $140,000, those making that much would have to shell out another $3,100 in payroll taxes. New Yorkers would be disproportionately affected by such a change since salaries tend to be higher here.

-- Increasing the payroll tax rate. A rise of only 7 percent -- from 6.2 percent to 6.65 percent for both employees and employers -- would allow Social Security to pay all its promised benefits at least until 2075, Robert McIntyre of Citizens for Tax Justice has written. But many supporters of lower taxes oppose hikes in either the payroll tax or in the wage cap.

--Investing revenues more profitably: Under federal law, Social Security can invest its funds only in securities issued or guaranteed by the federal government or guaranteed by the federal government. Some groups, such as AARP, have argued that a portion of Social Security funds could be invested more profitably.

THE OTHER DEFICITS

Some observers, notably Democrats, think the whole focus on the fiscal problems of Social Security is misguided at a time of massive federal deficits.

The White House has predicted that the deficit this year will rise to $427 billion. Some experts expect deficits could be far greater after Bush leaves office in 2009 because of tax cuts, the new Medicare prescription drug benefit and, if it passes, his proposal for private Social Security accounts. The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities predicts the Bush tax cuts and the Medicare prescription drug benefit will cost $19.2 trillion through 2078.

"Medicaid expenses in almost every state exceed that state's expenditure on public education: that is a crisis. Medicare has a life expectancy as a program of only about 15 years. So if you want to talk about real crises that the White House should be addressing, you'd start with those two programs,” Democratic Senator Richard Durbin of Illinois has said.

But Senator Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania, a Republican, said it makes sense to take on Social Security first – because it is so much easier to fix that than the health-care programs.

What is missing is a comprehensive plan to control the annual federal budget deficits. As another recent study (In PDF Format) has noted, deficit-reduction plans in 1990 (under a Republican president) and in 1993 (under a Democrat) raised taxes and cut spending. Both were key to the budget surpluses of the late 1990s. No similar move seems underway today.

THE POLITICS

So far, the public does not seem to buy the conservatives’ arguments for private accounts. A Washington Post-ABC News poll conducted earlier this month found that only 35 percent of those responding approved of Bush’s handling of Social Security, and 58 percent said that the more they heard of his proposal the less they liked it. Two-thirds of them, did, however agree with Bush that Social Security is headed for a crisis.

New Yorkers appear wary of private accounts, according to a poll (in pdf format) conducted last month by the School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University. Overall, 51 percent of New Yorkers oppose private accounts with 36 percent supporting the idea and the rest undecided. Among so-called Downstate New Yorkers – those living in New York City, Long Island and Westchester – results were more pronounced, with 54 percent opposing the private accounts and only 32 percent supporting them.

Most, if not all, state Democrats adamantly oppose the private accounts, and the one Republican member of New York City’s congressional delegation, Vito Fossella, has reserved judgment. “There are 100 moving parts to Social Security,” his aide, Craig Donner, told the New York Sun. “The White House said that personal accounts by themselves don’t ensure solvency. You have to see what the other 99 parts are before you an judge the plan.”

But even if Bush stumbles badly on this – Democrats fantasize that it could have the same devastating effect on congressional Republicans that the failed Clinton health plan had on congressional Democrats -- the Social Security debate presents hazards for Democrats. The party and many of its members have resisted presenting any solution of their own for Social Security’s problems. “To say there is no problem simply puts Democrats out of the conversation for the great majority of this country,” Democratic political strategists Stan Greenberg and James Carville have written. “Voters are looking for reform, change and new ideas, but Democrats seem stuck in concrete.”

A WALL STREET BOOM?

Regardless of what one thinks about the merits of the plan, if it passed, would it be good for New York? After all, the private accounts will be invested, and New York is the home to the nation’s financial industry. Increased business on Wall Street means more jobs, more salaries and bonuses for workers in the financial industry -- and more tax revenues for the city and the state.

University of Chicago economist Austan Goolsbee predicted(in pdf format) that fees on the accounts would bring Wall Street an additional $940 billion over the next 75 years, "the largest windfall gain in American financial history.” The Bush administration has disputed Goolsbee’s numbers, saying that the accounts would be managed by the federal government, avoiding such high fees.

And a report (in pdf format) by the Security Industry Association last year concluded that “ rather than a â€free lunch,’ Wall Street will realize only modest gains from these accounts.”

Even investment firms that see a big opportunity in the private accounts are soft peddling their support for them, afraid that their support would do more harm than good. "It could be wrongly used against advocates of reform, " Edward L. Yingling, incoming president of the American Bankers Association has said. And they worry about reprisals from unions, which adamantly oppose the accounts and could withdraw their huge pension funds from pro Bush firms.

But Tanner of the Cato Institute said that fees to Wall Street are not the issue. "The question is whether we're giving young workers more of a return [on investment] than they'll be getting today," he told the Washington Post.

For now, the dream of a Wall Street windfall has not swayed one influential New York billionaire and Republican. “I've never thought that privatizing Social Security made a lot of sense," Mayor Michael Bloomberg told reporters "I think what you'd see is that people would invest - some people would invest - unwisely....These are not monies that people should be speculating with."

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Organizations

AARP

The organization of older American opposes private accounts and cuts in benefits. Its web site includes information on Social Security

Cato Institute Project on Social Security Choice

The web site for the libertarian think tank that has been a major force in the push for private accounts.

Democracy for America

The organization, which grew out of Howard Dean’s unsuccessful presidential campaign, offers people the chance to read and submit stories about how Social Security has affected their lives.

Economic Policy Institute

A Guide to Social Security by a group that works to “promote a prosperous, fair, and sustainable economy.”

New Yorkers United to Protect Social Security

A campaign to urge Republican members of Congress from New York to oppose private accounts.

Social Security Choice

A project of the Club for Growth, this group advocate private accounts.

Social Security Online

The official web site of the federal Social Security Administration.

The Social Security Network

A project of the Century Foundation with arguments against private accounts, reports and links t9o news articles.

Strengthening Social Security

The official White House web site on Social Security

Articles

Bush's House Of Cards: The Privatization Fraud

Articles from American Prospect on Social Security and President Bush’s plan for private accounts.

Civic Elite Bets Social Security Loophole Loots

Some New Yorkers -- including four City Council members --already have private accounts.

American’s Senior Moment

Paul Krugman’s essay in the New York Review of Books looks at the demographic and fiscal problems facing Social Security and the country as a whole.

Q&A: The great Social Security debateÂ

WeCARE, For New Yorkers Still On Welfare And Unable To Work

More than half of the New Yorkers still on welfare are unable to work. Many have a medical condition, physical or mental; others have substance abuse problems. Another large group is too young or too old too work. A few are taking care of household members, or in some other situation temporarily preventing work.

The Human Resources Administration’s newest answer to this situation is WeCARE, an ambitious initiative intended to systematically address health and other issues. The administration expects to refer about 45,000 clients a year to several contractors offering employment services for people with disabilities.

Even critics of welfare reform welcome the city’s recognition that most current welfare beneficiaries face genuine barriers to work. A new source of vocational rehabilitation services and appropriate medical treatment could be just what many of them need to achieve financial independence.

However, the facts made public so far do not answer all the concerns of advocates for welfare recipients. The lack of answers may reflect holes in the plan for the new program.

What’s new about WeCARE?

The process will begin with a “biopsychosocial” assessment: a medical examination and tests, plus an interview about the client’s psychological and social history. This will put the client on one of four tracks: immediate work activities; immediate application for federal disability benefits; medical treatment for a current condition; or vocational rehabilitation.

This sounds very like the city’s PRIDE program, which ran from 1999 to 2004. It too attempted to redirect welfare recipients with disabilities into the workforce. In four and a half years, almost 37,000 participants were sent to PRIDE for assessment; of these, 5,800 found jobs and 3,100 were able to get federal disability benefits.

One difference will be that under WeCARE, a welfare applicant or client will be sent to a private contractor as soon as city workers learn of a possible barrier to employment. From then on, assessments, services, and case management will all be done by one contractor or its subcontractors. In the past, city workers retained many case management responsibilities for special-needs clients.

A larger difference, for people with disabilities, is that there will be new medical providers to evaluate and develop treatment plans for health conditions that can be stabilized. The clinic used for many years by the Human Resources Administration was considered by many clients to be too quick to dismiss their reports of disability, even when backed by medical records from personal physicians. As in the PRIDE program, beneficiaries will be required to undergo medical treatment. WeCARE staff will monitor whether they are carrying out their treatment plan.

Other than that, there are few new elements in the WeCARE program. In recent years, the city has screened welfare applicants for disabilities, substance abuse problems, literacy needs, English language skill deficits, and domestic violence; and staff have been expected to refer clients to appropriate services as needed. Those who reported having disabilities were sent to a clinic for medical and psychological examinations. Those who could work were sent to outside contractors for “skill assessment and placement” and, if necessary, for employment preparation and training.

The challenge of screening to find candidates for WeCARE

It is not clear how the Human Resources Administration will decide whom to refer to the WeCARE program. Effective screening for disability requires interviewers to explain the benefits of disclosing a condition: additional medical treatment and vocational services, the possibility of finding a job that is modified to fit their condition, and protection against discrimination.

Patience, respect for clients, and encouraging applicants to seek more services have not been the hallmark of welfare reform in New York City in the past. Under the PRIDE program, the city relied on welfare applicants to report their own physical or mental disabilities to job center employees.

This is likely to have excluded a number of applicants aware of having a condition that interfered with work, but not aware that their condition qualified as a disability, entitling them to accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act. People with arthritis or back pain may not know of any accommodations that could enable them to work without severe pain. Those with lupus or sickle cell anemia may have to take so many sick days that they cannot hold a job. Diabetics may need a workplace where they can store medication in a refrigerated space, and eat at specific times.

Still other people, on or off the welfare rolls, do not recognize the existence of a disability that interferes with their ability to work. Mental illness, for instance, can make it extremely difficult to look for a job, pursue vocational training, and/or navigate the Human Resources Administration’s procedures. However, the stigma associated with mental illness contributes to a widespread reluctance to face it.

One person can have multiple barriers to employment. Substance abuse or domestic violence might be the first ones identified. If the client does not trust a service provider, and the provider is not looking for the full picture, underlying physical or mental illness could go untreated, making other interventions useless.

Privacy issues in medical assessments

The WeCARE process puts its biopsychosocial assessment first, before the vocational assessment, and that raises privacy issues. Unless a client claims to have a disability that will interfere with work activities, welfare workers cannot assume that a visible disability is a barrier to work. An applicant cannot be ordered to submit to medical tests and questions about her psychological history as a condition of receiving welfare benefits.

Nobody is legally required to tell a WeCARE intake worker that they have a disability. According to the state’s Department of Labor, welfare applicants and beneficiaries cannot be forced to undergo medical assessment and treatment unless the government has “reasonable cause” to think that the client’s disability will prevent him or her from working. The Department of Labor suggests (In PDF Format) that a documented history of failure at work activities is required before medical examinations and treatment can be made a condition of receiving benefits.

However, waiting for failure at work activities is expensive for the city and discouraging for clients. It can lead to people churning through the welfare system without getting the help they need. Welfare recipients who lose benefits because they are sanctioned are more likely than other recipients to have major barriers to work, according to the Manpower Demonstration and Research Corporation. The Corporation recommends a combination of treatment and work support, such as that offered by WeCARE, cautioning that clients must be monitored on a long-term basis, to prevent deterioration during relapses or life crisis.

Who will train the job trainers?

The two contractors who will provide the bulk of WeCARE services are Federation Employment and Guidance Services (for Manhattan, Bronx, and Staten Island), and Arbor Education and Training (for Queens and Brooklyn). Both have experience in providing employment services under New York City contracts.

However, neither seems to be trying to staff the new program with workers with disabilities who could serve as role models for clients. Disability awareness is not a concept easily understood by those without disabilities. Without personal or work experience, workers may reduce complex situations to stereotypes, and apply a short list of cookie-cutter solutions to all problems.

The staffing plans of the two agencies, as shown in job descriptions posted on the Internet, require some managers to have education or experience in working with people with disabilities. However, no such requirements are listed for the frontline staff who will deal directly with clients.

Arbor plans to hire “intake specialists” to conduct the “psychosocial assessment” of new clients. Intake specialists may be hired with no education beyond high school, although they will be responsible for interviewing clients and writing summaries of their medical, psychological and social histories. Presumably, this report will play a large part in determining the path each client follows through Arbor’s system.

Medical compliance may be a stumbling block

The medical component of WeCARE is the Wellness/Rehabilitation Plan through which clients are meant to improve their health enough to be able to work. WeCARE will refer clients to appropriate providers, provide case management and health education, and monitor how well clients comply with doctors’ instructions.

It is not clear whether WeCARE case managers will be responsible for filing reports that lead to their clients’ loss of benefits. WeCARE staff are also supposed to help clients comply with treatment plans, and they can do this most effectively if clients trust and understand them.

WeCARE must expect that its clients, like other patients, will often fail to follow doctors’ instructions. Researchers estimate that when prescriptions are given to Americans with chronic diseases that have recognizable symptoms, patients take the medicine as directed only 60 to 70 percent of the time. Even medical professionals take medication incorrectly twenty percent of the time.

WeCARE meets Federal welfare reform reauthorization

After years of postponing it, Congress appears ready to address reauthorization of the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program, which governed the process of welfare reform. Hardliners want to make more welfare beneficiaries go to work, even though the people still on the rolls are those least able to get and hold jobs. The current law requires states to have half of their cases involved in “work activities.” The bill under consideration in the House of Representatives would raise the requirement to 70 percent of cases.

As of February 2005, 36 percent of the city’s Family Assistance recipients were working. The workweek now required is part-time; proposals to make it full-time threaten to prevent welfare recipients from taking part in valuable activities that don’t count toward the federal definition of “work.” For people with disabilities, sometimes the most essential job accommodation is a part-time schedule.

The city has already testified before Congress that raising work participation requirements will increase the need for federal funding of work supports. Higher requirements might also undermine WeCARE’s efforts to build on recent experience in welfare reform.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits.

The Working Poor

Last year, about one in three low-wage full-time workers in this city experienced one or more of these hardships:

- their gas, phone, or electricity was turned off because they couldn’t pay the bills;

- they used a food bank or pantry to avoid going hungry;

- they couldn’t pay the rent;

- or a prescription cost too much for them to fill it.

In The Unheard Third: Bringing the Voices of Low-Income New Yorkers to the Policy Debate, the Community Service Society and the United Way of New York City document the street-level effects of New York’s inadequate minimum wage of $5.15 per hour. Many of the working poor saw their wages or tips go down last year, had their hours cut back, or lost their jobs entirely. Statewide, over 88 percent of families supported by low-wage workers are headed by at least one adult over the age of 25; the minimum wage is not limited to teenage workers.

Those earning the least also receive the fewest employment benefits, which are taken for granted by higher-paid workers. Nearly two-thirds of low-wage workers reported having no paid vacation days or sick days. Almost half had no health coverage, with the majority lacking prescription coverage for themselves and/or health coverage for family members. The working poor have no need of financial advisors: Only one-third are offered a pension or 401(k) retirement plan, and most have less than $500 in savings.

There is little margin for emergency needs here. A parent who misses work to care for a sick child loses money every day and risks being fired. A few extra dollars a month for subway fare, or a four percent rent increase, means the family must do without another essential item.

Food Stamps Are Back in Favor

Under the Giuliani administration, food stamps were considered a form of welfare, and the city sought to “wean” working recipients from them. The Bloomberg administration has indicated more willingness to extend food benefits.

The city’s Human Resources Administration is collaborating with a food stamp outreach initiative of the Community Food Resource Center, with participation by Pathmark Supermarkets. The center will post advocates at supermarkets to educate shoppers about food stamps, screen them for eligibility, and help them fill out applications.

Little Help from Education and Job Training

While federal job training programs have a good record of helping graduates find and keep jobs, they are not reaching those New Yorkers who need them most. Statewide, less than one-third of 1% of adult high-school dropouts complete job training programs.

The city’s Local Law 23 mandated access to job training and education for welfare recipients, but the Bloomberg administration has not implemented the law, nor has it complied with a 2003 court order to provide a list of approved training programs to welfare recipients interested in enrolling. Nearly 80% of welfare recipients didn’t know that there were educational programs open to them, according to a survey by the Urban Justice Center and Families United for Racial and Economic Justice. For every two respondents who attended school last year, another seven were interested in doing so, but did not.

One unemployed woman had enrolled full-time in college before becoming eligible for welfare. She reported that a welfare worker told her that she would have to give up school in order to meet the work requirement. This was a direct violation of the city’s obligation to make a reasonable effort to accommodate the class schedule of a recipient enrolled in school.

Over 300 welfare beneficiaries were surveyed for the report, at ten of the city’s Job Centers. Such a survey would be more difficult today, now that an appeals court has upheld the city’s ban on the presence of advocates in job centers, unless they are on “official business,” as defined by the Human Resources Administration. [See “A Ban On Welfare Advocates At Welfare Centers,” by Emily Jane Goodman, Gotham Gazette, September, 2004.]

Better Days Are Not Ahead for the Working Poor

Currently, the working poor have limited opportunities to climb out of poverty, according to Between Hope and Hard Times: New York’s Working Families In Economic Distress (In PDF Format) , by the Center for an Urban Future and the Schuyler Center for Analysis and Advocacy.

The authors found that even before the recent recession, median household income dropped in all four outer boroughs during the 1990s. While the United States as a whole saw a slight drop -- 1.3 percent -- in the number of low-income households during that decade, New York State had an increase of 2.7 percent in its number of low-income households.

The hardships faced by low-income households are increased by New York City being one of the two most expensive places to live in the country. The cost for just three commodities—education, housing, and child care—illustrates the difficulty of working your way out of poverty.

A community college degree adds an average of $7,000 to a worker’s annual income, but tuition increases keep moving education further out of reach. New York City community colleges raised tuition to $2,800 a year in 2003. Students who work and go to school part-time aren’t eligible for the major source of financial aid: the Tuition Assistance Program.

Planned Shrinkage of Housing for the Poor

New York City’s permanent housing emergency continues to grow worse. Large new public housing projects are no longer being built. Poor tenants have come to increasing rely on Section 8, a federal program of vouchers that pay part of the rent, but there is a long waiting list for the program, and a likelihood that its funding will be cut next year. (See Affordable Housing in 2004 by Joe Lamport)

Inadequate Child Care

The city provides child care subsidies for 105,000 children; it is estimated that another 100,000 are eligible, but not receiving a subsidy. Low-income parents usually turn to unregulated care, such as leaving children with a relative or neighbor. Even among families using subsidized day care, 38,000 children are in unregulated care. Unregulated settings rarely offer the learning activities provided in more formal child care settings, so children entering school from unregulated day care start out with a disadvantage.

Work Supports as a Subsidy to Employers

Housing vouchers, child care subsidies, food stamps, and publicly funded health coverage can be seen as subsidies that benefit employers by allowing them to hire workers at salaries too low to live on. If government chooses to use tax dollars to help employers, there should be some criteria for this assistance. Perhaps businesses could be required to pay a living wage, with essential fringe benefits, unless they passed a means test based on their profit margin or on the salary of the highest-paid executive.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits.Â

New Programs Aim To Prevent Homelessness

With the homeless population at a record high and likely to get worse, thanks in part to an exhaustion of federal subsidy money and skyrocketing costs of providing shelter, two new projects — one funded by the Bloomberg administration, one by United Way of New York City -- are focusing on the prevention of homelessness. Homeless advocates are skeptical about both.

Six New Centers

Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s homelessness prevention strategy was kicked off this month with the opening of one of six new centers that will be run by community-based organizations. The centers are in areas of the city that send significantly more people to city shelters than other areas.

"It’s a very daunting task," said Mary O’Reilly of Catholic Charities of Brooklyn and Queens, one of the six organizations that will receive $2 million each year for the next three years to set up what are being called HomeBASE centers. "Our assignment is to really identify people most at risk of homelessness in Community District 12. And catch them at a point where we can prevent them going into the shelter system or becoming homeless."

The organizations are currently setting up office space, hiring staff and organizing themselves to accept clients. Much of their $2 million will be used to pay clients’ rent, often long overdue, in order to prevent their eviction. The rest will go to hiring staff – case workers and supervisors — who can work directly with people at risk of becoming homeless.

The Department of Homeless Services is having the organizations meet every two weeks to discuss progress. In their respective community districts, the agencies are each expected to serve 400 people annually who are in danger of becoming homeless. The people must be receiving public assistance or have low incomes. But beyond that, the agencies have some independence to tailor their programs.

Dealing With A Suitcase Full of Problems

These programs will be dealing with the many problems confronting most people who are in danger of becoming homeless, among them:

- Unemployment and underemployment

- Family discord/Domestic violence

- Mental and physical illness

“I have yet to see someone become homeless due to one problem,” said Renee Fueller, program director of the HomeBASE center that H.E.L.P. USA is operating in Community District 6 in the Bronx. “They usually have like a suitcase full of problems.”

At the same time, Fueller said, each agency is playing to its own strengths. "One of our strengths is employment training and placement."

Citizens Advice Bureau will operate a HomeBASE center in Community District 1 in the Bronx. It will help people through intensive case management to deal with family conflicts and mental health issues.

"Depression in particular is a serious problem that leads to homelessness," said Scott Auwater, Citizen Advice Bureau’s assistant executive director. "There are some people who simply cannot get out of bed in the morning." As a result, he said, they miss required appointments to receive benefits or fulfill obligations at city agencies that help them pay their rent. And they miss court dates at Housing Court, leading to a speedier eviction.

In addition, Citizens Advice Bureau said it would specifically focus on problems people have keeping their Section 8 rent subsidies. As many as 20 percent of people in city shelters, Auwater said, ended up in the shelter because they lost their Section 8 assistance. That is why Citizens Advice Bureau is participating in a study of Section 8 subsidies administered by the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development -- another effort to prevent homelessness.

In Queens, O’Reilly said Catholic Charities would look to helping people by tapping into a broad network of agencies that can help people in separate ways.

"We really think the community alliance is a key to success,” O’Reilly said, “There’s a strong network out there. We’re going to bring to that the folks in the trenches working in food pantries, at shelters, who are aware of the greater needs.

“What we’ve been found is that when we’re able to partner what we have with other organizations, there is a holistic approach that can fill the gaps,” she said.

O’Reilly cited her agency’s partnership with Community Mediation Services, an agency that helps families resolve problems that often tear them apart – leading some members to city shelters. In other cases, mediators can also intervene to repair broken landlord and tenant relationships.

Sounds Great, But Where Are the Resources?

Some advocates said the city’s new focus on prevention did not seem sincere.

"Everything they’re saying sounds great, there just are no resources yet,” said Patrick Markee of the Coalition for the Homeless. “You can’t say you’re going to prioritize prevention until you put resources into it.”

Mayor Bloomberg has cut city spending on prevention in every budget he has sent to City Council, Markee pointed out. And the homeless population has increased by 25 percent on his watch, he said.

“If you look at the mayor’s track record you can’t consider it as anything more than talk,” he said.

The city needs to commit significant resources to three areas to resolve the problem, Markee said:

- Financial assistance to help people pay rent arrears;

- financial assistance to help people pay ongoing rent;

- legal services to help people avoid eviction.

The United Way To Prevent Homelessness

A pilot project that the United Way of New York City is funding, and that is expected to be launched in December, will apparently focus on the third of these, the legal services. The agency is keeping many of the details of the project under wraps. In lieu of granting an interview, the organization gave me a statement:

"We're in the early stages of working with Justice Fisher and the housing court system to develop an innovative, holistic approach to addressing the needs of those confronting eviction,” said Larry Mandell, president and CEO of the United Way of New York City, in the statement, referring to Judge Fern Fisher, the chief administrative judge of the Civil Court of New York City. “Ultimately, we expect the program to help meet the short-term needs of clients in addition to examining longer-term solutions to prevent future eviction, but at the moment it's too early to talk about the details."

But a variety of sources at the court and at agencies in the Bronx who were familiar with the project said its approach will be to help people with their cases in Housing Court; lawyers will help tenants defend themselves in court while social workers will help them address the issues causing their problems at home or elsewhere.

A special court will be set up at Bronx Housing Court to deal with two zip codes where many more people than usual end up in city shelters, 10451 and 10455. Court papers will even bear a colored page to indicate that the person is assigned to the new court.

The United Way has awarded grants amounting to several million dollars to Legal Services for New York, which primarily provides legal services to low-income people, and to a community-based organization called Women in Need. The Office of Court Administration is also closely involved in the project, but like the United Way has declined to comment on it.

The project has incited a lot of speculation and comment in the court itself. Innovation in the court is not new. Two community courts in Harlem and Red Hook focus services on specific zip codes. But the resource centers in those courts offer limited assistance to tenants compared to what is envisioned for the United Way’s project.

Sounds Great, But What About A Legal Right To An Attorney?

Advocates said the United Way project would offer tenants helpful services, perhaps, but avoided dealing with the real problem in Housing Court: While most landlords are represented by attorneys, most tenants are not.“This is not about stopping people getting evicted,” said Judith Goldiner, staff attorney at the Legal Aid Society. “It’s all about window dressing. Maybe you get a little more money in there, make the landlords happy. But you seriously don’t want to get into what the issues are, which is that the landlords have lawyers and tenants don’t.”

Establishing the legal right to an attorney in Housing Court – the way defendants now have in criminal court -- would be more effective, advocates said. When tenants are represented they are much less likely to be evicted. The result is also more cost effective.

“I think the obvious and still true answer is that when people have legal representation they’re far and away more likely to retain their homes,” Markee said. “Landlords have lawyers, tenants don’t. If there were a right to counsel, we’d see far fewer evictions in Housing Court, that’s for sure.”

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations.

The Battle Over Social Security

The biggest domestic issue in the 2004 Presidential election has barely been mentioned by the candidates. More New Yorkers will be personally affected by the future of Social Security than by events in Iraq. George Bush has made it clear that "reforming" it will be high on his agenda if he serves another term. John Kerry has declared that he opposes privatization, the type of reform advocated by Congressional Republicans and the President.

Over 740,000 elderly New York City residents receive Social Security retirement benefits, plus nearly 290,000 younger spouses and children of retirees and disabled workers. About three out of five elderly Americans depend on Social Security for at least half of their income. Those who now receive Social Security benefits would not be affected by proposals on the table, which are limited to people under the age of 55.

The Social Security debate has been publicized as a choice between letting the government control the taxes we pay into the system, versus letting each individual worker invest his or her share of those taxes. Many Americans believe that Social Security funds will run dry before today's younger workers retire, and that if they could pay taxes into personal stock trading accounts, they would be able to invest their money more wisely than the government does.

In reality, the future of Social Security depends on factors no one can predict. Federal analysts make forecasts based on their assumptions; critics of the administration question both these assumptions and the conclusions drawn from them.

The Bush administration predicts that in 2042, the Social Security system will no longer have enough to pay the full benefit every recipient is promised under today's system. Even this is in dispute: the Congressional Budget Office thinks the system will be fully funded until 2052. To put the problem in perspective, the shortfall predicted by the Bush administration is about one-third the size of the federal revenue loss that will result if the president's income tax cuts continue.

Shortly after he took office, Bush appointed a Social Security Commission to propose reform measures. They developed three models for reforming Social Security which would allow workers to pay a small part of their payroll taxes-2 to 4 percent-into personal accounts managed by private financial investment companies, who would invest them in return for a small fee. Workers who chose not to participate would receive the amount they would be eligible for under the traditional program.

Conservative think tanks and Republican members of Congress have proposed more radical changes to Social Security. One bill introduced in 2004 would redirect half of the taxes now paid to Social Security into personal accounts. Other plans gradually reduce the minimum benefit guaranteed to retirees. Most require government subsidies from outside the Social Security fund.

Any reduction in Social Security benefits would disproportionately harm New York residents, because so many future retirees will be people of color, and people with low incomes. Currently the majority of New York States elderly residents are white, but that picture is changing. The state Office for the Aging estimates that by 2015, the number of minority senior citizens will have risen by 51 percent. Nationwide, the average white retiree depends on Social Security for less than 40 percent of her annual income. By contrast, Social Security supplies the average African-American and Hispanic retiree with 54 percent and 66 percent, respectively, of their income.

Today about one in six elderly New Yorkers lives in poverty. According to the Century Foundation, benefits under one proposal from Bush's Social Security Commission would have to be reduced by a third within three decades. The average elderly woman on Social Security now receives benefits of about $10,200 a year, only slightly above the poverty level of $9,310. If benefits were reduced by a third, many more New Yorkers would be impoverished.

For most Americans in the lower income brackets, their largest financial asset is their house, but few low-income New Yorkers own their own homes. Unlike home owners, renters cannot take out home equity loans when they need extra funds.

The Democratic Party platform opposes privatization. John Kerry quotes a University of Chicago economist, Austan Goolsbee, who estimates that the Bush Commission's proposals would give nearly a trillion dollars of Social Security money to the financial services industry. Goolsbee also predicts total benefits to retirees would be cut by up to 45 percent, and that investment expenses for personal accounts could consume 20 percent of the value of the average retiree's savings account.

Researchers opposed to privatization of Social Security believe the system does not need major changes. They question the assumptions of the Bush administration: that the economy will grow at half its former rate, while stock market growth remains the same.

Even if that inconsistent assumption is accepted, opponents believe that modest increases in payroll taxes and lifting the cap on taxable income would close the gap., The Social Security fund would be solvent for the next 75 years if payroll taxes were raised from 12.4 percent to 14.3 percent, an amount comparable to the rise under Ronald Reagan in 1983. In addition, earned income over $87,900 is not subject to the payroll tax; if this cap were lifted, relatively few wage earners would be affected.

Each year, Social Security checks bring about $8 billion into the New York City economy. Most of that money is spent quickly and locally, generating additional economic activity. Any action that reduces this inflow will harm New Yorkers of every age, as would the need to replace federal funds to support our aging residents.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits.

Portrait of Same-Sex (Married) Couples

With gay and lesbian marriages now legal in Massachusetts, court cases pending in that state and California, and President George W. Bush pushing for a constitutional amendment that would ban them, the issue of same-sex marriage is hardly a remote one.

How many New York same-sex couples would marry if they could? How many would then divorce? And how would they differ from heterosexual relationships?

The Same-Sex Marriage Market

As I discussed here before in New York City the census found 25,906 same-sex couples in "unmarried partner" relationships. Some of these couples marked "married," when they filled out their 2000 Census form, but the bureau recoded them as unmarried partners who had a "close personal relationship." (In 1990, the census added this new category "unmarried partner" to get at the large numbers of people, mostly heterosexual couples, who were living together in a relationship but were not married.)

Of course, counting the people who were in a same-sex relationship and were willing to tell the government about it is a poor way of determining the total number of gay and lesbian New Yorkers. But it probably is a reasonable estimate of the number of same-sex marriages we could expect over the short term if they were legalized in the city.

Many would probably not marry. According to the 2000 Census, about 1.1 million of the three million New York City households consisted of married couples, another 129,815 were opposite-sex unmarried partners, while there were just 15,016 male-male partner households and 10,890 female-female partner households. In other words, married couples accounted for 88 percent of all households headed by couples in New York City; unmarried opposite sex partners comprised 10 percent; and same-sex partners comprised just two percent,

Couples Compared

How do same-sex couples compare to couples of the opposite sex, both married and unmarried? Using data from the 2000 Census, here is my analysis, presented in the accompanying table:

Interestingly, same-sex couples share more with married couples than they do with unmarried heterosexual couples; the unmarried heterosexuals are younger, less well-educated, and less likely to own their own homes.

The male-male couples are much more educated and affluent than the other couples. They are also more likely to be white. The same-sex couples are more likely to be citizens and less likely to be foreign born.

Lesbian and Gay Divorce

Since same-sex marriage is not legal, there is no such thing as legal gay divorce in the United States, though recently there was the first gay divorce in Canada. However, in several countries in Europe where same-sex marriage has been legal for a number of years, we do have some information on the frequency with which gay couples formally end their unions. A recent study of divorce among gay couples in Sweden and Norway sheds some interesting light on the prospects for gay divorce in New York City. The researchers found that female-female couples were about three times as likely to dissolve their partnerships, and male-male couples were about one and one-half times as likely to dissolve their partnerships, as were married opposite-sex couples. The reasons for the higher rate of dissolution, especially among female-female couples, are not obvious from the study. Regular divorce proceedings are usually initiated by the female.

If same-sex marriage becomes legal we can be sure that there is a ready market for the institution among the roughly 26,000 same-sex couples that were willing to declare their partnership to the Census Bureau.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

The Poor Are Not Better Off

One week before the 2004 Republican National Convention, the Bush Administration announced that the nationwide caseload for federal welfare benefits dropped by three percent during 2003. Several days later, the United States Census Bureau reported that during the same year, 1.3 million Americans slipped into poverty. Now one in eight Americans is officially living in poverty, the third year of increases in a row. Here in New York City, poverty did not increase significantly, but it is not decreasing despite indications that the economy is improving.

What the changes mean for New York City

Between 2001 and 2004, over 140,000 New Yorkers stopped receiving benefits under the city’s Family Assistance program, which supports children and parents living together, generally in households headed by a single mother. Yet the overall count of welfare recipients is rising again, driven by “Safety Net Assistance,” a state program providing income assistance to adults without children, children living apart from relatives, and families who have reached the five-year limit for federal welfare benefits.

Since 2001, over 130,000 children and adults have been transferred into the Safety Net Assistance program because of the federal time limit. The fastest growing group on Safety Net Assistance is children living without adult relatives. Over the past three years, the number of recipients in this category rose from about 1,400 to nearly 13,000.

It’s Not the Economy!

Since the city is officially out of its recent economic recession, an optimist might assume that families are leaving welfare because more adults are working. In August 2004, the city’s unemployment rate hit its lowest point since September 2001. More single mothers are working: over 62 percent in 2003 compared to 59 percent in 2000. Among New Yorkers less than 25 years old, the share of women with jobs is now higher than that of men (and women are the ones who head most families on welfare.)

Despite these improvements, nearly one in three New York City children lives in poverty. Nationwide, only 17 percent of children are poor. (The poverty line is currently $15,670 a year for a mother with two children.) Black and Latino New Yorkers are more than twice as likely to be poor as white New Yorkers.

Meanwhile, local prices have risen by an annual rate of 3.5 precent over the first seven months of 2004. The costs of housing and food, the major expenses for low-income families, are going up even faster. The number of people declaring bankruptcy rose 50 percent more sharply in New York City than in the United States as a whole in 2003.

What Happens To People Who Leave Welfare?

A number of researchers have tried to discover what exactly is happening to people who leave welfare. The Urban Institute found that over 40 percent of former welfare recipients who lived with children had jobs in 2002. Another eight percent had a partner who was working, and seven percent had recently worked. Over one in four recipients were back on welfare, and four percent had begun receiving Supplemental Security Income, a benefit for low-income people with disabilities. That left 14 percent who were considered “disconnected” from the welfare system, defined as not working, nor living with an employed person, nor receiving cash assistance.

Among a sample of New York State families who left welfare in 1999, nearly three-fourths were unemployed when the Rockefeller Institute surveyed them 18 months to two years later. Of these, one in four was back on welfare, one in five was receiving federal disability benefits, one in six had a partner who worked, and a few received veteran’s benefits, unemployment insurance, and/or worker’s compensation. Other income sources were earnings from children aged 16 or more, gifts and loans from families and friends, and child support payments. Most families patched together two or more of these income streams to survive. More than half the members of the sample were getting federal food assistance, and nearly half lived in public or other subsidized housing.

Four percent of welfare leavers without jobs reported having no income, and used none of the in-kind supports used by others. It is possible that the survey undercounted such individuals, who can be hard to reach, if they have begun living on the street; turned to crime as a source of income; gone to jail, a hospital, or a mental institution; or left New York City.

The fragile financial balance of the families surveyed, even those with multiple income supports, led to frequent crises. At least a third were unable to pay gas, electric and/or telephone bills and had their service disconnected. One in five families was evicted or threatened with eviction. Many turned to food pantries and private charities, and one in twenty had to enter a homeless shelter.

Rejections on the Rise

Recently, the city’s Independent Budget Office reported that applications for welfare were more likely to be rejected in 2003, when the job losses were at their worst, than in 2001, when the recession had just begun. During the same period, job placements for welfare recipients dropped by a third, and applications for benefits rose. The Independent Budget Office estimates that if the city had kept its rejection rate down to the 2001 level, an additional 25,000 cases would have been opened in 2003.

When new mothers in 20 United States cities were surveyed, it turned out that nearly half of those who were eligible for welfare benefits did not receive them during their baby’s first year. During the recession year of 2001, less than half of all eligible families received welfare benefits; before welfare reform, about 80 percent of such families were getting assistance.

Food stamp use is widespread and growing

Food stamps are more widely used than welfare, because more people are eligible under their higher income limits. A Cornell University researcher has estimated that 40 percent of all Americans will use food stamps at some point during their working-age years. The risk varies with race and educational level: an African-American woman without a high school diploma has a 90 percent chance of using food stamps, while at the other extreme, a white male college graduate has only a 37 percent chance of using food stamps.

There are over a million people on food stamps in New York City, with another 700,000 believed to be eligible. After years of shrinking the list of food stamp recipients, by making it difficult to apply for assistance, and easy to be cut off by mistake, the city has succeeded in raising enrollment for the past two years. The state is making its own efforts to help qualified residents receive benefits. New York was the first state to automatically continue food stamp benefits to people leaving welfare, for a transitional period that now lasts five months. The state has also announced its intention to automatically mail food stamp benefit cards to all recipients of Supplemental Security Income, whose income is by definition low enough to entitle them to food assistance.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits.

A Ban On Welfare Advocates At Welfare Centers

A group of Brooklyn community activists has lost its six-year legal battle for access to the waiting rooms of welfare offices, now known as Job Centers. The group's staff attorneys and volunteers had sought to provide information, literature and translations, as well as to act as advocates for welfare recipients and claimants at the centers.

The group, Make The Road By Walking which was founded in 1997, describes itself as a membership-led organization whose hundreds of members are primarily low-income Latino and African-American residents primarily of Bushwick, Brooklyn. Make The Road (its name comes from the saying "We make the road by walking.") engages in community organizing, offers training, and provides services.

In the case of Make The Road by Walking, Inc. v Turner, the federal courts have upheld New York City's ban on the presence of advocacy organizations such as Make the Road by Walking and the Legal Aid Society in welfare waiting rooms. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals, the federal court just below the Supreme Court of the United States, in a unanimous opinion by Judge Ralph K. Winter, affirmed the lower court's dismissal of claims of First Amendment and other constitutional violations.

In 1998, Make The Road By Walking requested access to the Job Center waiting rooms "to assist, inform, and represent claimants." The Job Centers are the division of the Human Resources Administration (HRA) that dispenses benefits, including welfare, Medicaid and food stamps. The city responded in writing that, "HRA declines to grant the access you seek, other than for the purpose of providing representation to a specific applicant or recipient."

After being denied access to the waiting rooms except to those who had previously been retained and were on the premises to represent a specific client, the organization filed the federal lawsuit in The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York on the legal grounds of the First Amendment, due process and equal protection. Judge Allen G. Schwartz dismissed the major claim, granting summary judgment to the city. (Judge Schwartz, who has since died, was, prior to his appointment to the federal bench, New York City's Corporation Counsel during the Koch administration.) He found that the city's policy would prevent overcrowding, and disruption in the waiting rooms, and would protect welfare claimants from becoming confused, and was therefore reasonable and concluded that there were no First Amendment or other constitutional violations.

All parties agreed that the speech of Make The Road By Walking is protected by the First Amendment. "However, notwithstanding that freedom of _expression... is a fundamental right, essential to our democratic society and accorded great weight by our courts, nothing in the Constitution requires the Government freely to grant access to all who wish to exercise their right to free speech on every type of Government property without regard to the nature of the property or to the disruption that might be caused by the speaker's activities."

For First Amendment purposes welfare offices are not public in the way that streets and parks are. While they are public in the sense that anyone can walk in, visitors not there on "official business" will be asked to leave. Judge Winter found that Make the Road By Walking was not there on official business as defined by the City and that the government had never intended to open the Job Centers to the public. Therefore, the waiting rooms are nonpublic.

In determining that the centers are nonpublic, the appeals court opinion draws on the legal history of welfare advocacy in welfare centers (including references to some fights that broke out when welfare applicants did not receive the benefits the advocates told them they were entitled to), during the 1970s and 1980s, when access was permitted, as well as Supreme Court decisions in the areas of free speech and solicitations in other venues such as airports and army bases. The court concluded that government intent was key, and that "the use of HRA premises shall be limited to the transaction of official business and such other activities as may be specifically authorized by the HRA ... . Distribution of written material is limited to releases issued or sponsored by HRA... . HRA defines its official business and 'limits third party access to Centers and their waiting rooms to those individuals who are part of the transaction of HRA's official business.'"

The Court of Appeals has now determined that the centers are not public because the government does not intend them to be public, that the restrictions on speech in a non public forum are reasonable, that the presence by Make The Road By Walking was not for "official business" even if its business was welfare rights, and that the organization's staff might cause "vulnerable claimants" to feel confused and exploited. With this decision, Make The Road by Walking has reached the end of this road.

No information was available about an appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States. Make The Road By Walking was represented by The Brennan Center for Justice, The Welfare Center, New York Legal Assistance Group and White & Case. The City was represented by Corporation Counsel.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

The Disabled Poor: Shut In, Out of Pocket

Many low-income people with disabilities never have a chance to apply for Medicaid, food stamps, or income assistance because they literally cannot go to all the offices required.

The Human Resources Administration has a policy to remedy this situation: Caseworkers can visit applicants and clients at home.

However, when investigators from the Welfare Law Center visited welfare offices, its report (In PDF Format) reveals, the staff at only about half of the offices suggested home visits for a hypothetical applicant with a disability.

The center's researchers went to Job Centers in all five boroughs, asking the person at the information desk in the waiting room for information for a friend who had no food or money, and needed to apply for benefits but was unable to come in person because of severe depression.

Workers at four of the 30 Job Centers flatly denied that home visits were available, and those at ten other Job Centers required persistent prompting before they said home visits were possible. At two of those ten centers, workers could not give any information about how to get a home visit -- not even a phone number to call for more information.

These findings are especially disappointing because in March 2003, the Human Resources Administration introduced a new policy meant to meet its legal obligation to accommodate people with disabilities. It suggests changes in the way appointments are made, such as scheduling them to avoid conflicts with medical and mental health appointments, and rescheduling when there are disability-related reasons.

However, the policy does not require agency staff to let the public know that home visits are available, and to offer visits to people who do not explicitly ask for them, no matter how visible and severe their disability. Nor does the policy stop agency staff from continuing to send notices ordering clients to come in person to a Job Center, even after they have proved that they cannot.

"Many people are sanctioned for not showing up for one appointment," Cary LaCheen explains. When someone misses an appointment, the agency notifies them that they have 10 days to come into the welfare office and explain why they missed the appointment. This doesn't help people who can't come to the office at all, LaCheen points out.