Pay Equity for Probation Officers in New York City

Probation officers in the community (photo: @nycprobation)

When I was a college senior, I didn’t quite know what I wanted to do with my life, but I knew I wanted a career where I could make a difference in my community. I sent my resume to a number of City agencies and was offered a job as a Probation Officer Trainee. This has led to a long and fulfilling career at the Department of Probation.

What appealed to me about working in probation was the opportunity to give people involved with the criminal justice system a second chance, while working to keep our neighborhoods safe. I rose through the ranks, eventually becoming a Supervising Probation Officer and ultimately becoming the first black woman to serve as President of my union, the United Probation Officers Association.

One of the challenges I face as a black woman in a leadership position, leading a union that is not big and being “the new kid on the block“ is that I am often not taken seriously or respected. When I speak our truth, I must be mindful not to come across as that “angry black woman.” I am still trying to figure out how we as Probation Officers can get a seat at the table, to be seen and receive the support of political leaders who claim to value and understand our work.

While I am proud of the work I have done helping my fellow New Yorkers turn their lives around, it has been incredibly frustrating at times. Women, particularly Black women, are used to doing important work that holds communities together. And yet we’re rarely fairly compensated for it. You’ve probably heard the statistics before, but they’re worth repeating: women, on average, earn 81 cents for every dollar a man makes, and Black women make 61 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic males.

You’d expect a city as progressive as New York to be doing better. But a recent report from the New York City Council found that women working in city government earn 73 cents for every dollar men make. Inequities exist along racial lines too, with Black city employees making 71 cents to every dollar made by white workers, Latinos making 75 cents to every dollar in pay whites get and Asians making 85 cents compared with a dollar of a white person’s pay.

Pay at the Department of Probation illustrates how the work of women and people of color is overlooked and undervalued by the city. Not too long ago, our department was staffed by mostly white male employees, but over the years more women and people of color have joined the ranks. Today, approximately 80% of probation employees are female, and over 90% are nonwhite.

Over time, the city has suppressed salaries in the Department. Today, our compensation lags other law enforcement agencies in the city, and probation departments in neighboring counties. Last year, the City Council conducted an analysis that looked at pay disparities in City agencies. The results were clear: Probation employees were paid far less than Department of Corrections employees, even though Probation Officers perform similar job functions as Corrections Officers and have higher educational requirements. The difference is that our agency is mostly women and people of color, while Corrections is mostly male.

This is simply unacceptable. New York City should be a leader in promoting pay equity and respecting the work of Black women. We should have a municipal government that acts as an example for treating women and people of color with dignity. Instead, they are preserving the status quo. How can we expect the private sector to treat their workforces fairly when the city is exploiting women and people of color who have dedicated their lives to public service?

We've taken the city to court to address the pay disparities our members face. We hope that the Adams Administration will be more receptive than its predecessors were to our very legitimate concerns, and work with us to ensure hardworking Probation Officers are paid what they're worth.

Last month was National Black Women’s Equal Pay Day. I spent the day reflecting on what world we want our daughters to grow up in. I want the girls who will grow up to look like me to be treated fairly, and to know that what they contribute to society is just as important and valuable as that of any man.

***

Dalvanie K. Powell is the President of the United Probation Officers Association, the union representing more than 650 active and retired Probation Officers and Supervising Probation Officers. On Twitter @UPOA3.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Aiding Domestic Violence Survivors and Addressing the Crisis on Rikers Island

Protesting conditions on Rikers (photo: Gerardo Romo/NYC Council Media Unit)

Stephanie grew up without a stable family and ended up in an abusive relationship with a boyfriend. A cycle of physical and emotional violence continued for years, leading to Stephanie giving him drugs while he was in prison, which resulted in her incarceration.

When she was released and returned to the city, Stephanie’s boyfriend raped her, and she became pregnant. Afraid for her life, she went to a domestic violence shelter. Stephanie’s parole officer claimed that she didn’t provide her change of address and that she tested positive for drugs, which she denies.

In 2018, she ended up at the Rose M. Singer Center (Rosie’s) on Rikers Island. Pregnant, and suffering from sleep apnea, Stephanie was in a life-threatening medical situation. After three months the court agreed that Stephanie could leave Rosie’s and instead be placed with SHERO, which provides transitional housing and services to women, gender-expansive people, and their families.

Like Stephanie, 93% of women diverted from Rikers Island have experienced domestic violence: physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, according to a recent report by the Women’s Community Justice Association and the Rikers Commission. Nationally, an estimated 77% of women in jail have experienced intimate partner abuse

With 16 deaths on Rikers already this year, there is an urgent need to decarcerate. As we honor Domestic Violence Awareness month, one way that New York City can address the Rikers crisis is to ensure that domestic violence survivors are diverted from jail and instead given the community-based resources they need to heal.

It should start with strong preventative services that help those suffering from domestic violence avoid criminal legal system involvement in the first place. That includes access to physical and mental health care, legal services, and affordable places to live. Economic independence is also crucial, but those with criminal records face barriers to hiring, professional licensing, and housing. Passing city and state laws that remove these unfair restrictions would help more families who have endured abuse to thrive financially and avoid the devastating cycle of incarceration.

The next step is to get domestic violence survivors off Rikers and into community-based alternatives. There should be holistic screening for physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and other factors, such as mental illness, by peer specialists who have lived experience with the criminal legal system. These considerations should be used by judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and others involved at every stage of a case.

In 2019, New York passed the Domestic Violence Survivors Justice Act, which has judges take into account a history of abuse when determining sentencing. Having domestic violence considered earlier in the case, including for bail and charging decisions, would help to get more survivors off of Rikers more quickly.

Finally, there should be better access to programs like SHERO, which has diverted Stephanie and over 300 women and gender-expansive people from Rikers since it launched in 2017. It costs $60,000 to $70,000 annually for a program slot at SHERO, compared with $550,000 to incarcerate someone at Rikers.

While at SHERO, Stephanie gave birth to a healthy baby. “I had my own apartment and case managers that listen and care about me,” she said. “This is a community of women who support each other. I’m in culinary school and working towards my dream of becoming a chef.”

New York City must do more to protect and support domestic violence survivors whose trauma and experiences leads them to Rikers Island. Strong community-based resources that prevent incarceration and a focused effort to more quickly divert those at Rikers into alternatives would improve safety and justice.

***

Michelle Feldman is the Policy and Campaigns Director for Women’s Community Justice Association, which advocates to end mass incarceration for women and families in New York. On Twitter @WomensCJA.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Mayor Adams, If NYC Schools are ‘Segregated Intentionally,’ Why Increase Segregation with More Admissions Screening?

Mayor Adams talks with students (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

On September 29, the Adams Administration announced changes to the high school and middle school admissions process for the 2023-24 school year. Most significantly, middle schools, which had been unscreened for the last two academic years, can resume academic screening of fifth-grade students in admissions if the district superintendent so chooses.

Admissions to New York City high schools are the nation’s most competitive. The most coveted schools admit students on the basis of grades, state test scores (when available), and sometimes school-specific interviews, evaluations, and essays. The “winners” of the competition receive a free ticket to an education comparable to elite private schools. For those students who come from poor and working-class families, admission to “brand name,” well-resourced public schools can be life-changing.

But what of the “losers” who vastly outnumber the “winners”? As one high school student observed: “People say numbers don’t lie. Good, smart students get good grades and are thereby entitled to the city’s bulk of resources. The rest of us are left to fight over the scraps. That is the logic of our school system.”

Even some winners pay a heavy price. Black and Latino students who are offered the opportunity to attend one of the highly selective New York City high schools (including but not limited to the specialized schools such as Stuyvesant and Bronx Science) can feel marginalized. One Black student reflected: “Everyday walking through those doors I feel alienated, like a single piece of black pepper in a sea of salt…School should be considered your home away from home, yet all I can feel at school is out of place.”

High school screens will remain in 2023-24, with one substantial tweak: students whose grades are in the top 15% of their school–or in the city as a whole–will have priority in admissions to the city’s most coveted public high schools. This change could, in theory, increase racial and ethnic diversity in these schools to a certain extent, since middle schools are highly segregated by race and class.

However, coupled with other changes to the admissions process, a Department of Education (DOE) spokesperson told Chalkbeat New York that the city expects the changes to increase racial and socioeconomic diversity of students at screened schools as compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic, but not compared to last year.

In my research on historical and contemporary segregation in New York City schools, it became clear to me that students wish to attend a school where they feel a part of a community, and one that has sufficient resources. Finding such a school has long proven elusive for many Black and Latino students.

They may attend a co-located school that shares its building with five other schools; the demographics of these schools and the resources allocated to them often are starkly different, highlighting the vast disparities in the system.

Most devastatingly, Black and Latino students may feel their schools are “not good enough” for white students. As one former student told me about her “mainly Black and brown” school: “If you saw any white kids in the school it was like…‘What happened?’ It’s almost like: ‘How’d ya get here?’ You’re supposed to be in a better school with better academics. And because they were white, a lot of the kids just assumed they were a lot smarter than us. They put [the white students] on a pedestal–because of how much of our academia was lacking.”

These are the fruits of segregation and excessive screening. By late 2017, former Mayor Bill de Blasio had brought hope to integration activists by launching the School Diversity Advisory Group (SDAG) and naming Richard Carranza as Schools Chancellor. SDAG’s extensive recommendations to reduce segregation and increase equity resulted in little concrete action, an occurrence that echoed the demise of previous city panels on integration. Carranza spoke passionately about the need for integration, insisting in Spring 2019 that “we will not wait to dismantle the segregated systems we have!” By August, he conceded: “If I integrated the system, the next thing I’m doing to do…is walk on water.”

Shortly thereafter, SDAG released its second and final report on school diversity. Among its recommendations were the unscreening of all middle schools and some high schools. In the six months before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, de Blasio said virtually nothing about any such changes being implemented. However, in a covid-era change that integration advocates hoped would become permanent, mIddle-school admissions for the 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years were unscreened.

Those desires were dashed by the current administration’s recent announcement. Despite Adams’ insistence last November that city schools are “segregated intentionally,”

his administration has revealed little appetite for meaningful school reforms aimed at increasing integration and equity. At the recent news conference announcing the admissions changes, School Chancellor David Banks justified rigorous screening by arguing that hard-working students with high grades “should not be thrown in a lottery with just everybody.” It is wrong to classify students whose grades do not reach the top tier in this way. The less-than-stellar grades of a 12-year-old should not relegate them to the school system’s “scraps.”

There is a lot of work to be done in a school system with 1 million students, 85% of whom are students of color and more than 70% of whom are low-income.

District superintendents should resist pressures by influential parent groups to resume screening of 10-year-olds for middle-school admissions. The un-screening of middle schools brought some promising, if modest, changes to the racial and economic demographics of the most highly-regarded middle schools–at least in districts with considerable diversity. The system didn’t collapse.

Thoughtfully and deliberately increasing racial and economic integration in schools remains a crucial step for the city to move beyond its longstanding model where there are a smattering of “great” schools for the “winners,” and a much larger number that are short-changing their students.

***

Christopher Bonastia is Professor and Chair, Department of Sociology, Lehman College, and Professor, CUNY Graduate Center. He is the author of The Battle Nearer to Home: The Persistence of School Segregation in New York City (Stanford University Press). On Twitter @Uno_Collison.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York Must Brace for a Recession; Where Things Stand and What Comes Next

Gov. Hochul talks budget (photo: Darren McGee/Office of Governor Kathy Hochul)

The Federal Reserve Board’s aggressive interest rate increases have put the nation and New York on notice that an economic downturn is a serious possibility. The Board is determined to wring inflation out of the economy, and forecasts higher unemployment but no recession. Nonetheless, New York’s leaders need to brace for one.

The nation has suffered through two vastly different recessions in the past 14 years. The COVID-19 pandemic is fresh in our memories; the Great Recession of 2008-2009 was not an economic lockdown brought on by a deadly disease, but a financial and industrial meltdown followed by a slow recovery.

In 2008 I was still in the New York State Assembly and had a bird’s eye view of New York’s escalating financial problems and our struggles to cope with them. This time around it looks like the State is far better prepared than it was then, when the State had virtually no reserves. By contrast, New York City seems less well prepared than in 2008, when it had much higher financial reserves, but its property tax base may give it the stability it needs to ride out a recession.

I wish someone would tell the Federal Reserve to stop raising interest rates and let what it has already done cool the economy rather than risk a recession, but it doesn’t look like the hawks at the Fed would listen. So what should New York do to prepare?

New York State: The First Year of Covid

New York became the nation’s epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. By the beginning of June 2020 about 30,000 New Yorkers had died of the disease. Between February 2020 and April 2020 New York State lost 1.9 million jobs, 20% of its overall employment and 23% of its private-sector employment, compared to 14% and 16% nationally, respectively.

The state government, anticipating a giant recession, adopted a budget plan in April 2020 allowing the Governor to cut up to $10 billion from the state budget and permitted New York to borrow unprecedented sums of money if necessary. A few days before the state adopted its budget, then-President Trump signed the $2 trillion CARES Act intended to preserve the economy primarily through direct relief to individuals and businesses. Then-Governor Cuomo and other leaders pressed the federal government until December 2020 to add more relief for state and local governments.

On December 27, 2020, Trump and Congress enacted a new $900 billion stimulus package, adding relief for individuals and businesses but also adding support for state and local governments, especially for education.

By March 2021, it became clear that predictions about staggering tax revenue losses in New York in 2020 turned out to be wrong. New York’s tax revenues for the 2020-21 fiscal year barely declined at all, from $82.9 billion to $82.4 billion, although the State had recovered only about 1 million of the 1.9 million jobs it lost during the lockdown.

The State’s Tax Base

It turned out New York State could have big job losses but not lose tax revenue because of its tax base. New York State obtains 60% of its revenue from the income tax.

Even as the pandemic wreaked havoc among sectors of the economy like leisure, hospitality, and retail, jobs in the affluent office sector, like finance, technology, and business services, did not suffer large declines. The office sector workforce was for the most part able to work remotely, and some still paid hefty bonuses while the wealthy continued to pay taxes on capital gains income from the stock and real estate markets. Those high incomes sustained high tax revenues even while more than a million people had lost their jobs.

The New York State income tax base is pictured in this year’s budget and shows the concentration of income and tax liability for the years 2007, 2009, and 2019, the bookends of the Great Recession and the year immediately prior to COVID, which is the last information available.

Looking at 2019 makes it clear how 2020 finances took the path they did, as well as the path the state’s finances took in the Great Recession:

The data show the extraordinary concentration of income and income tax liability in New York. In 2019, the top 1% had 29% of New York’s adjusted gross income and 50% of its non-wage income, and paid 42% of its income taxes. The top 10% had 57% of the income and 69% of the non-wage income, and paid 72% of the income taxes.

Low and middle-income residents are surely paying plenty of taxes in comparison to the levels of their incomes; when you add sales, property, social security, and income taxes together on the incomes of the middle and working classes, they are paying plenty. But the data can explain how even as one portion of the workforce is experiencing great pain, the state’s income tax revenue can hold up from another portion without job and income losses. It also shows what can happen from a recession connected to a financial meltdown, such as what occurred in the Great Recession.

The New York Budget and The Great Recession

In the adopted state budget of 2009-2010, New York closed a $20 billion deficit, $2.2 billion from 2008-9, and $17.9 billion for 2009-10.

Governor Paterson’s press release from the time of budget adoption described how the state balanced its budget: $6 billion in spending cuts; $5 billion in tax increases (mostly on the wealthy); and $6 billion in federal aid. The state had little reserves; they were a minimal factor in balancing the budget.

The Concentration of Income and Liability table above shows how a financial meltdown can affect the budget. New York’s adjusted gross income falls 17% over the two-year period (from $631 to $520 billion), non-wage income falls 38% ($270 to $167 billion), while wage income falls less than 3% ($412 to $401 billion). The crash in non-wage income is primarily the drop in capital gains. Tax payments fall, while deficits explode, because governments build budgets based on projections that plan for increased revenues and increased spending.

The Covid Recovery: Tax Revenue Rockets Up

President Biden signed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan into law on March 11, 2021. The plan included stimulus payments, state and local government financial support over several years, including a tranche of 2023 support, additional education funds, vaccine distribution funds, and other health care support.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the nation has gained 8.3 million jobs since March 2021, from 144.4 million to 152.7 million. According to the New York State Labor Department, New York State has gained 596,000 jobs, from 8.919 million to 9.515 million, with New York City accounting for 406,000 jobs, rising from 4.147 million to 4.553 million.

New York’s healthy economic growth, driven by the American Rescue plan, job increases, the boom in the stock market, Wall Street profits and bonuses, and a tax increase on the wealthy and large business enacted by the Legislature in April 2021, resulted in the state’s tax revenue taking off like a rocket.

From April 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022 (NYS Fiscal Year 2022), the state’s tax receipts grew an astonishing $22 billion, or 27%. The Governor and the Legislature responded with largess for the budget year that began in April 2022. There was a 7% school aid increase, $2 billion to backfill unpaid rent and utility bills from the pandemic, more than $1 billion for bonuses for health care workers, major funding for child care expansion, $2.5 billion in property tax relief, and gas tax relief. The State Division of Budget plan projected surpluses this year and for the next several years, and the state made a significant deposit into reserves.

New York Flush with Cash, Didn’t Spend It All

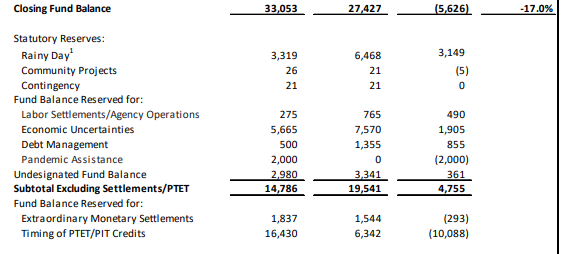

The State Budget Director, Robert Mujica, who worked for Governor Cuomo and was retained by Governor Hochul, must have had the Great Recession in mind when planning for the state FY2023 budget. The Legislature was persuaded to save billions from the surplus cash that flowed into the State Treasury in 2021. As of this July, the state was so flush that it anticipated having a cash balance of $27 billion in the General Fund by March 2023, of which $19.5 billion could be accessible for an emergency, excluding special obligations. See NYSDOB, 1st Qtr. Update, p.25:

FY’22 FY’23

A New Recession in New York May Be Like 2008-09

The Federal Reserve’s hawkish actions to curb inflation upended the Division of the Budget’s rosy projections within just a few months. The State DOB’s First Quarterly Update (April-June 2022) recognized the Federal Reserve’s actions to slow the economy would halt the revenue boom. Surpluses would turn to deficits and next year, FY 2024, would see a $3 billion deficit. Deficits in future years would grow. The update was written in August, before the Federal Reserve’s next big interest rate increase, and the DOB will surely increase the size of the state’s deficits next year and beyond due to the slowing economy.

Big stock market declines, plunging Wall Street bonuses, and a drop in real estate transactions mean big tax revenue losses even if job losses are modest because the wealthy already pay such a large share of New York’s taxes. Even in a recession, they stay wealthy, their incomes just decline temporarily. But that’s why a recession in New York could be similar to 2008-2009. This time New York is fortunate all that cash is sitting in reserve funds.The state will need the reserves to mitigate the economic impact of the downturn and preserve services, especially if there are no new federal funds for another bailout of state and local government.

What To Do

-Substitute Borrowing for Use of Cash in Capital Projects

The state plans to transfer $4 billion in cash in 2023 and $6 billion in 2024 to avoid selling long-term bonds to pay for capital projects, a large increase in the use of cash for capital projects compared to past years. This is prudent but the state doesn’t have to do this. It is discretionary.

The cash could be used to support the operating budget if necessary during a recession. Borrowing several billion is not a bad thing, capital projects are appropriate uses of borrowed funds. The state could also defer certain capital projects to preserve cash.

The state also has the ability to borrow short-term for operating purposes, as long as the money is repaid by the end of the fiscal year. If necessary, the state could borrow several billion next spring to cushion spending as the economy is monitored. It could use its reserves to repay the money at the end of the year.

-Use the Reserves, That’s Why They’re There

The State has enough flexibility to use $5 billion a year, even for more than one year, to protect services. Obviously it would be unwise to use all of the reserves.

-Use Federal Aid from the American Rescue Plan

A third and fourth year of federal support for state and local government provides $2.4 billion in 2024 and $2.3 billion in 2025. The state can use these funds as it wishes, including simply shoring up its existing budget.

-Postpone, Even Modestly, Planned Spending Increases

The state cannot really hide completely from a downturn that results in lower revenues. It has planned a $3 billion (10%) increase in school aid in 2024 to strengthen Foundation Aid. It can stretch that out further. The state’s child care expansion is only $100 million extra in 2024 and that should be sustained; it is not very costly.

New York City and Recession

New York City has now recovered 85% of the jobs lost during the lockdown, not as high as the nation, but it lost 23% of its employment in the lockdown, compared to 14% nationally so it has had much further to go to recover. It would be a shame if Federal Reserve actions thwart the city’s recovery.

The healthy recovery enabled the city to use $6 billion in surpluses to prepay expenses for this fiscal year, which began July 1. However, federal aid this year (FY 2023) has dropped closer to normal, $9 billion. As a result, surplus cash is likely to be unavailable next year and the projection is that the city will have a $4 billion deficit. This was the projection at budget time before the Federal Reserve Board’s aggressive actions.

State Comptroller DiNapoli’s August 2022 report on New York City’s Financial Plan warned that risks to the city’s budget could increase the city’s deficit next year to $6 billion (some of which appears to be an unavoidable pension shortfall of $870 million).

The comptroller’s report indicated that a recession similar to 2009 could result in $4 billion in revenue losses to the city next year. Both the comptroller and the Citizens Budget Commission have been urging the city to build its reserves, which are lower proportionately than what the city had available in 2009. Mayor Adams is implementing a Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG), curtailing spending now across city agencies.

The city’s newest fiscal challenges, from Texas sending refugees to the state mandating class size reductions for the school system, call out for state and federal help, especially given the risk of a recession. The city has one backbone for revenue: the property tax, which historically has held up even in downturns.

The city has $8 billion in reserves and, as a last resort, could enact a highly unpopular property tax increase. The city needs to maintain, even increase, its capital program and invest even more funds in affordable housing and conversion of office space to residential. During the next state budget process, Mayor Adams will need a truly focused effort to get the state to acknowledge the need to help its largest city.

In the Great Recession, the breakdown of the state budget lasted three years, from 2008-2011, in major part because it had no reserves to fall back on. This time, the state may be able to manage a soft landing in New York, even while the rest of the country has more problems than we do.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York's Opportunity to Purchase: Help Stabilized Renters Buy Their Buildings

Affordable housing (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Rent increases begin for roughly one million rent-stabilized New York City apartments on October 1, the highest increases since 2013.

Fallout from the pandemic has strained landlords, especially owners of smaller multi-family rental buildings, and it has also dramatically impacted families who were already struggling to pay even below-market-rate rents.

At the “raucous” Rent Guidelines Board meeting about the increases, tenants advocated for rent freezes and rollbacks while landlords argued for higher increases.

Here is a strategy for our city to help both landlords and tenants: create opportunities for rent-stabilized New Yorkers to buy their buildings.

Converting existing rental buildings into shared equity homeownership opportunities will enable renters to experience the generational wealth, health, and educational benefits of home equity. Owners who are already thinking about selling will have an opportunity to do so in a way that delivers dollars and social impact, strengthening our city.

As I gathered with world leaders recently as a delegate to the Clinton Global Initiative, I was honored to introduce the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Program (TOPP) as our “commitment to action.” TOPP will convert 350 rental apartments into permanently affordable homeownership opportunities on a community land trust, providing access to homeownership for future generations of low-income New Yorkers.

Through TOPP, tenants and multifamily building owners will access technical assistance, housing finance, and construction preservation expertise. It’s a win/win/win scenario that is scalable as a model for all like-minded, mission-driven businesses and organizations to transform tenants into owners.

Affordable homeownership is a uniquely powerful tool for creating more equitable communities. It creates community assets that protect families from displacement, immune to the vagaries of speculative investment.

It offers self-determination of where to live and how long to stay.

It fosters more civically-engaged residents, and, through rental-to-ownership conversions, provides opportunities to make energy efficiency improvements to mitigate climate change and reduce energy costs.

Perhaps most importantly, affordable homeownership creates infrastructure for equity, as an urgent response to centuries of racist housing laws and financing mechanisms that prevented communities of color from entering the homeownership market. This legacy continues to shape the geography of the wealth, health, and education inequality we see today in our city where 41% of white people own homes, while only 27% of Black people and 16% of Latino people do.

We estimate that roughly 95% of tenants who will become homeowners through TOPP will be Black or Latino New Yorkers in communities that have lengthy histories of disinvestment and redlining. With well-resourced investors buying potential starter homes as they hit the market and converting them to market-rate rentals—and with affordable housing construction focused almost exclusively on rental housing—now is the vital time to implement new homeownership strategies to close the racial homeownership gap.

By addressing housing affordability and equity through affordable homeownership conversions, we as a city can build a more equitable New York, addressing several of our most pressing social and economic challenges at once.

***

Karen Haycox is CEO of Habitat for Humanity New York City and Westchester County. On Twitter @HabitatNYC_WC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The MTA Must Fix Its Defective Assessment of Congestion Pricing

Clearer streets on the way (photo: Marc A. Hermann/MTA New York City Transit)

Damage continues to mount from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s bungled environmental assessment (EA) of congestion pricing.

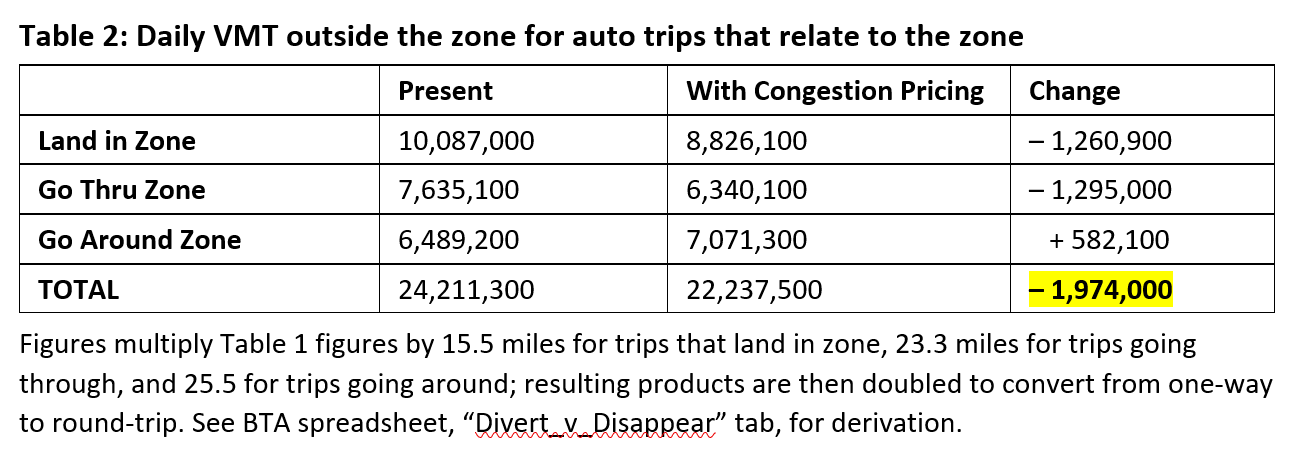

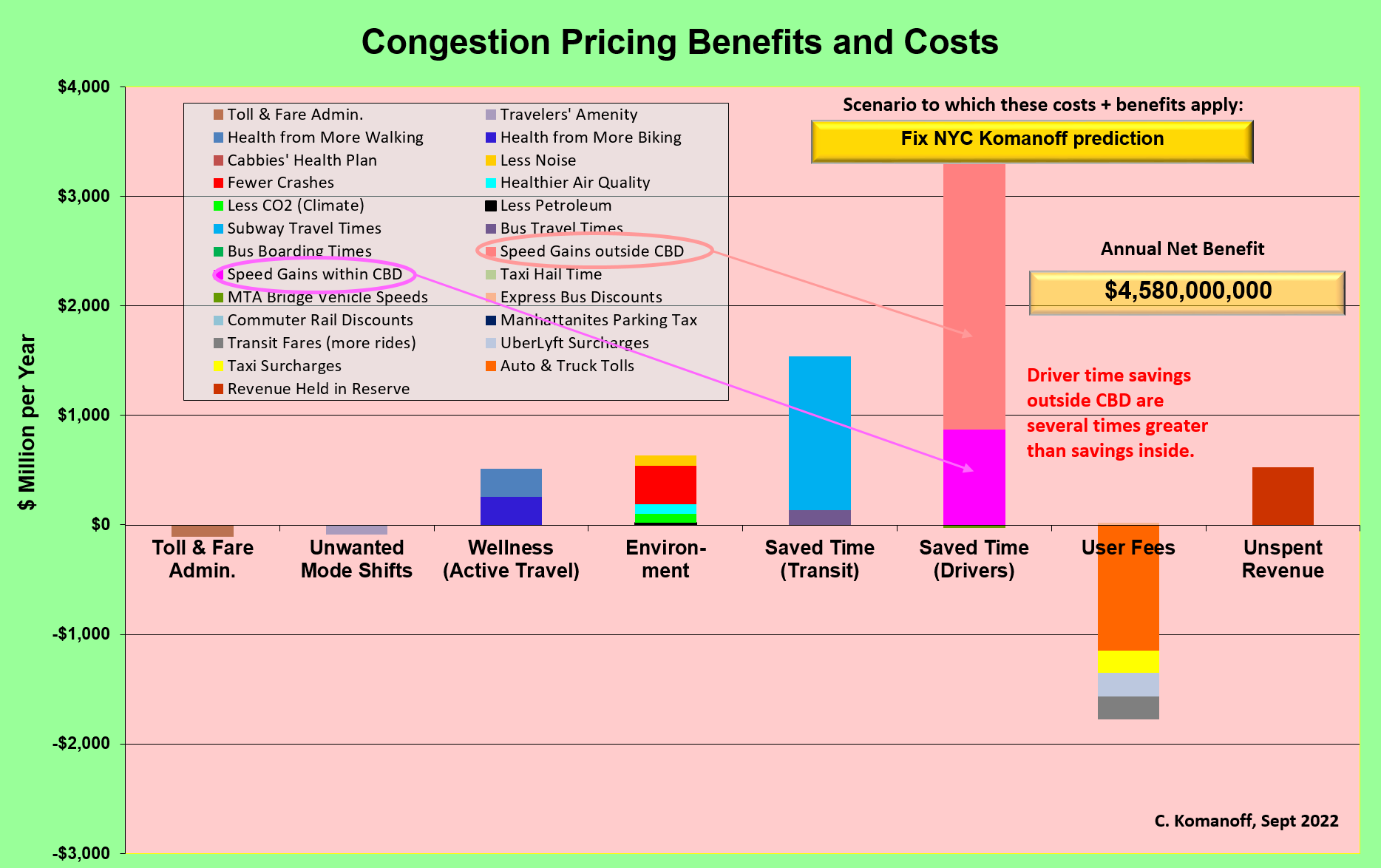

With its sprawling, 46-volume EA, the MTA took a proven policy idea, so well-suited for New York that it was destined to bestow $10 million worth of travel-time savings to drivers across the region every day, and turned it into a dog: a money grab that will cut traffic only in Manhattan.

While that “finding” is nonsense, it has a whiff of plausibility. Congestion pricing will cause some car and truck trips that now go through Manhattan from New Jersey to Long Island to divert around the island. Some will go west to east via the Bronx, others will divert to the south, across Staten Island. But the MTA has grossly exaggerated this effect.

According to my new analysis, the authority has also understated this offsetting effect: the tolls will result in elimination of 10 to 15% of auto trips from around the region that now go to the Manhattan core, and that habitually congest the boroughs and counties through which they pass en route.

These errors add up to an average five-fold underestimate in the EA of cuts in traffic volumes outside the Manhattan core because of congestion pricing. For the bulk of the region — the four “other” boroughs plus Westchester, most of Long Island, and the closest New Jersey counties (Essex and Hudson) — traffic volumes will fall by an average of 2%, a palpable cut, rather than the EA’s nothingburger forecast of 0.4%.

Put differently, for every vehicle-mile of car traffic that congestion pricing will eliminate within the Manhattan pricing zone, eight vehicle-miles will disappear outside the zone.

Were these findings in the assessment, the storm of criticism of congestion pricing since the EA’s August 10 release would have been far less intense. Instead, as the final push approaches, congestion pricing has seemed at times to be shedding public support. And no wonder. For a wonky, seemingly newfangled scheme like congestion pricing to actually come into being, it must bring big, broad benefits, not perks for a small and relatively wealthy minority.

Making matters still worse, the face of the assessment, and thus of congestion pricing itself, soon became its forecast of more heavy trucks spewing exhaust on and around the poster child of transportation injustice, Robert Moses’ Cross-Bronx Expressway. Yet the fact is that even with such an increase, the Bronx as a whole would still enjoy slightly cleaner air due to lesser atmospheric conversion of regional exhaust into toxic particles. Even better, the shrinkage in traffic volumes promises to cut air pollution across the board as fewer combustion engines spew emissions, fewer vehicle tires are ground into airborne particulates, and trucks’ driving speeds even out somewhat with improved traffic.

The prospect of lower traffic volumes throughout the region puts the lie to the idea that only residents of Manhattan stand to benefit from congestion pricing. True, the proportional fall in traffic volumes will be most pronounced in Manhattan, but traffic volumes region-wide will shrink so much that the reductions outside the zone will far exceed the reductions within it — again, by eight-fold, per my calculations.

This finding also refutes the idea that congestion pricing is “only about the revenue.” Rather, congestion pricing will not only raise revenue to improve subway service — the economic lifeblood and equity linchpin of our city and region — it will materially cut traffic, even without crediting the “carrot” effect of better mass transit luring some trips from automobiles.

How Did the MTA Get Congestion Pricing’s Traffic Benefits Wrong?

Following the August 10 release of the MTA’s environmental assessment, I tried for weeks to ferret out the “price elasticity” in the “best practices model” (BPM) the authority used to estimate how congestion pricing will change traffic and travel.

I theorized that the BPM grossly understates the extent to which making it costlier to drive into or through Manhattan will induce drivers to “mode-switch” to public transit or carpool or give up the trip altogether. I also wondered if MTA staff running the model had mathematically misapplied price-elasticity in a way that would compound the undercount of eliminated car trips.

I came up empty. The MTA modelers ignored my entreaties to share info, and their model, a product of the age of mainframe computers, is impenetrable. However, I learned last week from a source that the BPM does not even employ price-elasticity, which translates percentage increases in trip costs into percentage decreases in trip volumes. It may instead model trip choice through the physics concept known as “impedance,” treating tolls and other trip costs in a manner analogous to increased resistance to electric current flowing through a wire.

Somehow, this got me thinking differently about the MTA’s modeling. If the big flaw in the environmental assessment was that it understated traffic reductions outside of Manhattan, I would try to calculate how congestion pricing would change “vehicle miles traveled” (VMT) in those areas.

My Qualifications to Assess Congestion Pricing

Since I am counter-posing the MTA’s congestion pricing findings with my own, I should state my qualifications to quantify congestion pricing’s impacts.

I have spent much of the past 15 years developing and updating an elaborate (“kaleidoscopic,” I like to say) Excel spreadsheet model of New York City traffic and transportation known as the Balanced Transportation Analyzer.

The “BTA,” which I continually update and keep in the public domain via this permalink, has over 80 interlocking worksheet “tabs” that are stocked with baseline travel data and connected by over 100,000 equations and algorithms. These tabs “communicate” with each other and recalculate traffic volumes and other outputs whenever users enter inputs that correspond to congestion tolls and/or dozens of other potential policy changes. Data inputs are made easily in a single tab, allowing them to be processed in minutes or even seconds, and the calculation of results is instantaneous.

The BTA’s rigor and its ability to output the impacts of policy changes such as congestion toll levels led to its being made the primary analytical tool used by New York State’s “Fix NYC” panel to scope congestion pricing in 2017-2018. (The Fix NYC panel report has been scrubbed from New York State government sites but is archived at my website; the report’s Appendix B dedicates two pages (pp 32-33) to describing and lauding the BTA.)

To my surprise, this year the MTA’s environmental assessment team used my spreadsheet to select the toll levels it then evaluated for its various tolling scenarios. (See Central Business District (CBD) Tolling Program, Appendix 4B.1, Transportation: Transportation and Traffic Methodology for NEPA Evaluation, p. 1-2.) The team did not, however, use the BTA to estimate the number of auto trips to or through the congestion zone that would be eliminated under the different toll scenarios.

My VMT Analysis of Congestion Pricing

Conceptually, my analysis was simple: I drew on the estimates in the BTA of two categories of daily auto trips: (i) those that presently “land in” the congestion zone, or central business district (CBD), and (ii) those that drive through the CBD, from west of the Hudson River (New Jersey) to geographic Long Island, i.e., the boroughs and counties east of the East River (Brooklyn, Queens, Nassau, Suffolk), or vice-versa. From the latter figure, through-trips, I was able to estimate the number of auto trips with similar origins and destinations (NJ to east of the East River, or vice versa) that drive around rather than through the Manhattan core.

How did I estimate the number of auto trips that now, without congestion pricing, drive around the zone? I compared the costs of a typical trip through the zone to one around it, accounting for fuel costs and travel time (both of which are calculated from assumed trip distances), as well as any pre-existing tolls, such as the Port Authority tolls to travel eastbound through the Lincoln or Holland Tunnel or over the George Washington Bridge.

By constructing probability distributions around these mean costs, I was able to calculate that, under present conditions, out of every 100 trips with those origins and destinations, the less expensive route is through the zone for 56 trips, and is around the zone for the other 44. I then posited that trips seeking to go from New Jersey to Brooklyn/Queens/Long Island (or vice versa) adhere to those proportions, meaning that, without congestion pricing, 56% of those trips go through the Manhattan congestion zone while the remaining 44% go around.

I then “perturbed” my baseline assumptions of driving speeds (and, thus, travel times) and tolls to reflect prospective changes from congestion pricing. The result was that the share of trips from west of the Hudson to east of the East River (or vice versa) that will find it less expensive to go around the zone increased to 48%.

Translated to trip volumes, this 4 percentage point rise in the share of go-around trips equates to 11,400 additional trips “diverting” around the congestion zone per day, as shown in Table 1 below.

That is only part of the congestion pricing equation, however. The other, and arguably more impactful part, is the outright elimination of auto trips (and not just their rerouting) as the congestion toll pushes some trips “underwater” economically, in that the net value of the auto trip for the trip-taker turns negative. These trips may switch to train, bus, subway, bike, walk, carpool, new destination, or no destination (i.e., the trip is canceled).

For my calculations I assumed that 1/8 of the auto trips that currently land in the congestion zone will be so eliminated, with a somewhat smaller fraction, 1/10, of west-of-zone to east-of-zone (and vice versa) auto trips being eliminated. The 1/8 figure is consistent with my congestion pricing modeling for trips bound for the zone; the lower 1/10 figure takes into account the poorer transit alternatives for trips that pass through or go around the congestion zone, while also reflecting the fact that trips landing outside the Manhattan core tend to create less economic value for motorists, rendering them more vulnerable to the impact of the congestion toll than trips bound for the zone itself.

These assumptions result in the before-and-after volumes of trips that pertain to the congestion zone, either by landing in it or going through or around it, shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Daily Auto trips that relate to the Manhattan Congestion Zone

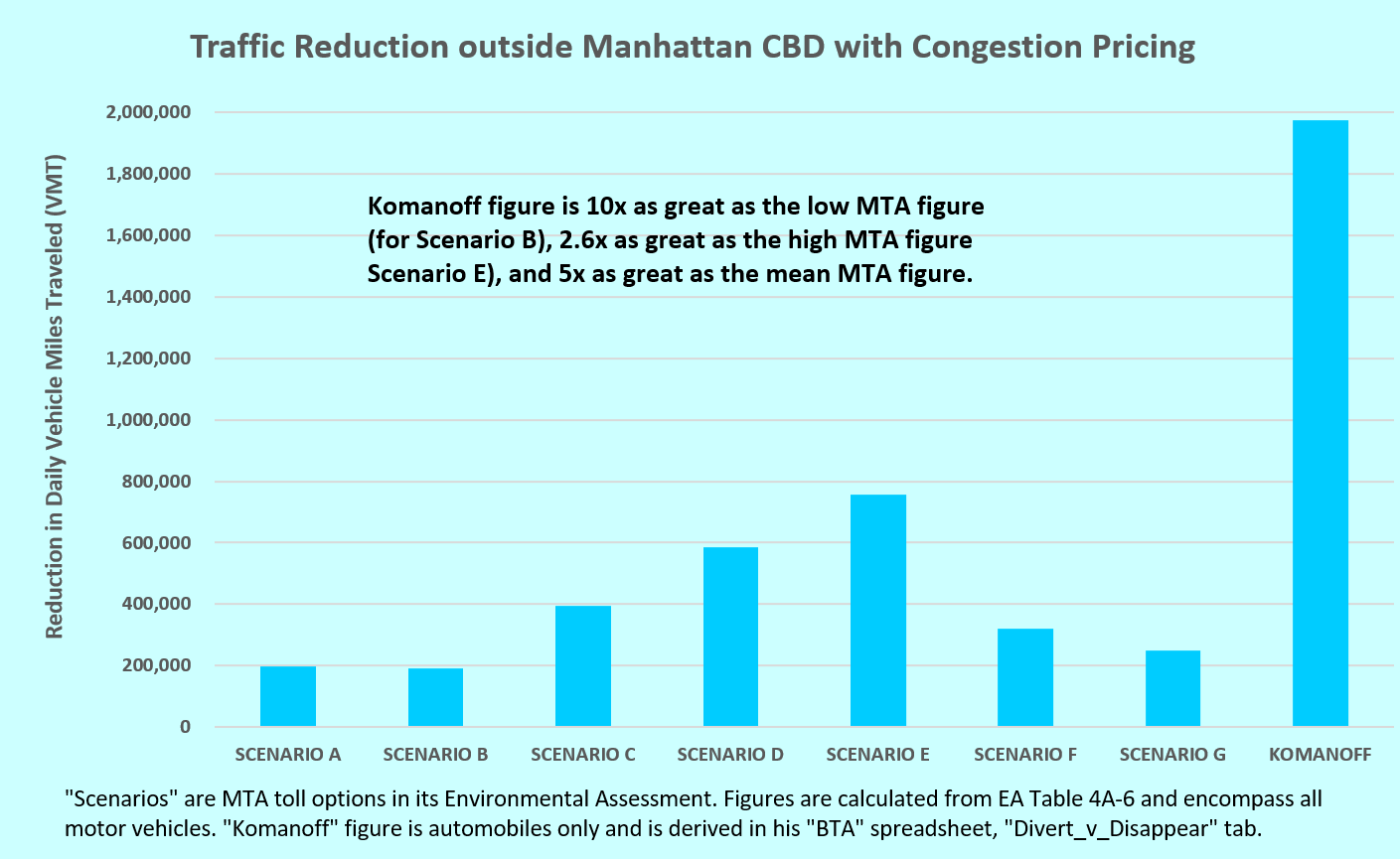

Table 1 is only an intermediate result. The goal is the changes in non-CBD (non-zone) mileage for each category of trip. These are shown in Table 2:

Table 2: Daily VMT outside the zone for auto trips that relate to the zone

The literal bottom line in Table 2 indicates that congestion pricing will result in 1,974,000 fewer daily miles traveled by automobiles outside of the Manhattan congestion zone. The 582,100 daily increase in VMT from the uptick in trip diversions around the zone is swamped by the combined 2,555,900 decrease in VMT stemming from the elimination of trips to and through the congestion zone.

Now consider the projections in the environmental assessment (EA) for reduced VMT outside the zone. These range from a low of roughly 190,000 (Toll Scenario B) to a high of 760,000 (Toll Scenario E) and average 385,000 (Toll Scenarios A-G). I computed those figures directly from the Environmental Assessment’s Table 4A-6: Daily Vehicle-Miles Traveled: No Action Alternative and CBD Tolling Alternative, by Tolling Scenario (2023).

My estimate of the reduction in VMT outside the congestion zone, 1,974,000 miles per day, is 2.6 times as great as the EA’s high figure, 10 times as great as the low figure, and 5 times as great as the mean.

The Meaning of 2 Million Fewer Miles Driven Outside the Zone Each Day

My estimate, nearly 2 million fewer daily auto miles driven outside the congestion zone, is hard to grasp. To put it in perspective, consider that the combined present-day automobile VMT for New York City (outside of the congestion zone) plus most of Long Island, all of Westchester County, and the New Jersey counties closest to the CBD (Hudson and Essex) is around 100 million. (That figure is rough-calculated from Table 4A-6 in the EA.) Since most auto trips into and through the CBD originate from those districts, it’s fair to say that my estimate of just under 2 million miles a day of reduced auto VMT outside the zone equates to nearly 2% of current auto traffic in those areas.

An average 2% reduction in traffic volumes outside the congestion zone is no small thing. It promises cleaner air, quieter and safer streets, and faster, easier travel for motorists and truckers. Indeed, that promise is a key part of the bedrock on which congestion pricing advocacy has been built.

Refuting the Notion that Congestion Pricing is Manhattan-Centric

The same EA Table 4A-6 referenced above gives the MTA’s projected reductions in VMT inside the congestion zone for the seven toll scenarios. These average around 250,000 miles per day. Compared to that figure, my estimate of nearly 2,000,000 fewer vehicle miles traveled outside the zone is around eight times as great.

While there is an element of apples/oranges to this comparison (the 250,000 figure employs the MTA’s methodology whereas the 2,000,000 figure arises from mine), the contrast is so stark that it should dispel the notion that only residents of Manhattan stand to receive congestion pricing’s bounty of lesser traffic.

A Caveat

In analyzing before-and-after cost-preferences for driving through versus around the congestion zone, I chose to add only $5 to the tolls that motorists driving into Manhattan via the Holland or Lincoln Tunnels will face with congestion pricing.

That figure is intended as a rough true-up of the current Port Authority tolls to cross the Hudson River ($13.75 peak, $11.75 off-peak) to the eventual congestion toll that will likely be $15 or somewhat higher. In other words, I have chosen to assume that the congestion toll won’t be applied in its entirety on top of the incumbent Port Authority tolls.

Nevertheless, relaxing that assumption by adding $15 rather than $5 in congestion tolls to the two Hudson River tunnel crossings reduces the calculated reduction in non-CBD VMT from congestion pricing by only 10%: to a little under 1.8 million from a little under 2 million. It thus appears that my finding of substantially less VMT outside Manhattan is not terribly sensitive to my assumption that motorists crossing into Manhattan via the Port Authority tunnels won’t face the entire congestion toll as an increment in the price of their trip.

An Invitation

My key result, that congestion pricing will shrink daily VMT outside the congestion zone by nearly 2 million miles, is of course an artifact of assumptions as to toll rates, the value of motorists’ time, distances covered, highway and street speeds, etc.

I invite readers to input their own assumptions and see how the calculated VMT result changes. Unlike the MTA’s Best Practices Model, my BTA spreadsheet is in the public domain and is easily manipulable for the sake of sensitivity analysis. As noted the BTA is available for downloading (17 MB Excel spreadsheet, go to “Divert_v_Disappear” tab).

In Closing

Congestion pricing was always going to have to be fought for, every step of the way, not only to enact the legal authority, as was accomplished in the New York State Legislature’s March 2019 budget bill, but to actually put it into practice. We advocates were ready to help ensure that the congestion toll program was put into fruition. However, we should not have had to help beat back the tidal wave of opposition that has engulfed the program since the MTA’s environmental assessment was released, which arose largely from the assessment’s faulty modeling and unfounded results.

Those results should be withdrawn. Contrary to the MTA’s assessment, not just the Manhattan core but the entire city and region are poised to enjoy material reductions in traffic volumes and, with them, the panoply of economic and quality of life benefits that congestion pricing proponents have long touted to our fellow New Yorkers: quieter, safer streets; more accommodating environments to walk and bike; cleaner air; speedier bus service; easier goods logistics and delivery; and, above all, improved travel times for users of automobiles, yellow cabs, ride-hail services, buses, and trucks.

My own modeling puts these “net” benefits (“net” in the sense of deducting the tolls paid by motorists, the cost to install and operate the tolling infrastructure, and the lost value of the trips that the new toll will “price off the road”) at some $4.5 billion a year — around $12.5 million a day. Denying that benefit, as the MTA’s environmental assessment essentially does, by grossly undercounting traffic reductions across the city and region, qualifies as an “own goal” of monstrous proportions. I call on the MTA to reboot its analysis and finish the job of leading congestion pricing through the bureaucratic wilderness and to fruition as soon as possible.

***

Charles Komanoff, long-time New York policy analyst and environmental activist, has been quantifying congestion pricing's costs and benefits for 15 years. On Twitter @Komanoff.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

White House Hunger Summit Must Get Real About Poverty to be Successful

Emergency food (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

The White House will soon convene a conference on hunger, nutrition and health – the first of its kind in over five decades. In that time we have made great strides in reducing food insecurity, but the changes are not all good. After an explosion of unhealthy, cheap foods, diet-related diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension have become some of the leading causes of death. The goal of this conference is therefore not only to end food insecurity but to increase healthy eating and physical activity to save lives.

This conference has five pillars, all necessary to help create a complete picture of health. But the first pillar – access and affordability – holds the key to achieving the success of the other pillars.

I have spent much of my career in nutrition and research and appreciate the need to integrate four other pillars to combat diet-related diseases with access, physical activity, education, and research. But if we acknowledge the true extent of poverty in America, then the anchor pillar, food access and affordability, must be well-funded.

Food insecurity is about poverty. It’s about not having money to buy food after you’ve paid your rent, electricity, a metro card, gas, or your medicine co-pay. It’s about not having places to buy fresh food in your neighborhood, or the money to buy fresh food when it is available.

Poverty is political. More realistic thresholds would reveal the true extent of poverty in the United States. And even with the too-low thresholds we use today, poverty at 11% (which some people would applaud as it is at its lowest) is not good enough. We can do better, and we have.

During the last two years – when we increased the child tax credits, offered free meals in school for all, reduced arduous paperwork to apply for help, opened avenues for non-citizens to receive support – poverty rates, particularly among children, decreased even more. We should institute these changes permanently.

We should also look at poverty numbers without fear, creating more realistic thresholds, supporting more people to grow up healthy.

The poverty threshold is calculated annually by the U.S. Census Bureau as the amount of money required for a family or individual to meet basic needs. There are no regional differences. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services then uses the results to set guidelines for eligibility for federal programs such as food assistance. The guidelines are the same for 48 states (Hawaii and Alaska are the exceptions because they are not mainland).

The poverty threshold uses an archaic equation that was created in the mid 1960s and is simply the cost of a minimum food diet multiplied by three to account for other expenses. It is updated annually for consumer price changes, but the same antiquated equation is maintained. There is a newer model called the supplemental poverty measure that includes noncash benefits as well as housing and other costs but this is not used universally. The fact that the basic equation is simply the cost of a minimal food diet is also concerning if we are hoping to increase health as well as reduce hunger. Fresh food costs more. Minimal won’t do.

We must vary the threshold to accommodate those who live in more expensive cities, and those whose incomes are subject to different minimum wage laws. It is unfathomable that someone who lives in a rural area and someone who lives in New York City, for example, receive the same benefit.

A woman with one child in 2022, for example, is considered poor if she makes less than the poverty threshold of $18,310. The guidelines then allocate benefits based on a percentage over the threshold. Using New York City as an example, where the minimum wage is $15 an hour, if that woman worked full-time, and depending on deductions, she would either be ineligible for SNAP (food stamps) or receive a paltry $23. Here is a person who lives in a city where the cost of living is very high, and she is doing exactly what the government wants her to do, yet she cannot even get adequate help to buy healthy food. If eating healthy is vital to being healthy, then the SNAP allocation should reflect that. It might, if the poverty thresholds varied.

We have the power and the tools to end hunger and food insecurity in the United States. Now we need the will. I’m excited for this White House conference. I’m excited that the government is serious about helping everyone eat healthy and be healthy. Let’s finally make healthy food available and affordable for everyone in the United States and watch as the other four pillars begin to take root and bear fruit.

***

Cathy Nonas is the CEO of Meals for Good, former Senior Advisor in the Center for Health Equity at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and an NYU McSilver Fellow-in-Residence. On Twitter @mealsforgood.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Keeping Kids, Families, and Communities Safe as Children are Back to School

Getting vaxxed (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Back-to-school is traditionally an exciting time for parents, teachers, and educators. With New York City returning to school this month after COVID-19 kept children isolated from classmates and, in many instances, interrupted routine medical visits, experts fear the population will have lower immunity and be behind on routine vaccines.

The city continues to work its way out of the pandemic and encourage "back-to-school checkups." Let's ensure the whole family is up to date with their vaccinations and healthcare needs.

If your child has not had a checkup in the past year, you should schedule an appointment with your pediatrician. We not only ensure that the child is up to date on immunizations but also evaluate growth and development, nutritional status, and behavioral, developmental, and psychosocial issues that may impact school performance. Schools and public health officials are reminding parents to get their kids caught up on recommended childhood vaccinations or risk the genuine threat of the return of illnesses once mostly eliminated.

Since the Pandemic, vaccination rates have plummeted and not yet rebounded, leaving school-age children vulnerable. During the 2020-2021 school year, vaccination coverage decreased by one percentage point for U.S. kindergarteners compared to the prior school year, the CDC found, and infant vaccination rates also dropped between 2019 to 2020.

New Yorkers remember that in 2019 there was a measles outbreak in Brooklyn, and we’re seeing the case numbers rise around the country and worldwide; we are seeing the return of this and other diseases once thought eradicated. Worldwide measles cases increased 79% for the first two months of 2022 compared to 2021. Additionally, New York State health officials confirmed the first case of polio in the U.S. in almost a decade in Rockland County and another in New York City.

Pandemic restrictions and virtual education reduced kids' risk of contracting measles, mumps, rubella, and other communicable diseases, and masking, testing, and contact-tracing helped keep covid and other illnesses from spreading through classrooms at higher rates. However, the arrival of the more infectious Omicron subvariant underscored how quickly things could change significantly since schools can be breeding grounds for community spread. For example, in March, Los Angeles Schools saw a spring flu outbreak that resulted in school administrators closing school for in-person attendance.

Covid vaccination rates lag in teenagers and children. Unfortunately, we are now contending with more vaccine hesitancy. Vaccinations are more crucial than ever, especially as we see polio detections. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that more than four in ten parents will not vaccinate their children under five years old against the COVID-19 virus. However, to protect against measles, 95% or higher herd immunity is necessary, and if vaccination rates dip, especially in local communities or schools, outbreaks are possible.

When our schools start to return to normalcy, our city cannot handle a massive polio outbreak that could disrupt our children's education. However, according to a CDC analysis, vaccination coverage against measles for kindergarteners nationwide in the 2020-2021 school year was 93.9%. Public rates show that almost 14% of young New York City children haven't received a polio vaccination. To protect our schools and our children, parents must ensure their kids are vaccinated.

We all want a "normal" school year after the last two-plus years of living in a pandemic, but we need everyone to do their part. That's why we urge families to remember to vaccinate their children to keep them and their families safe from outbreaks. It will take all of us working together to make this school year magical.

***

Dr. Andrea Perry, MD, MBA Pediatrician, is Medical Director at EmblemHealth. On Twitter @EmblemHealth.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

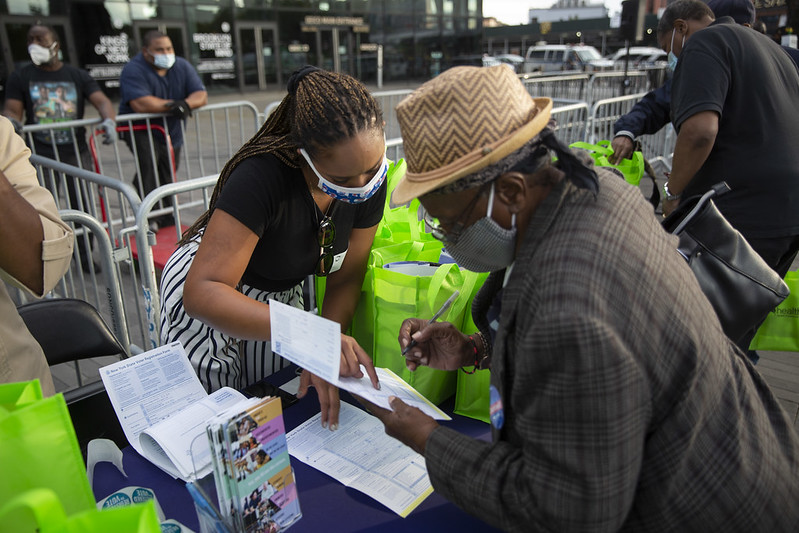

Worried About the 2022 Election? 3 Ways to Get Organized and Make Change

Organizing New Yorkers (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

It’s fall in New York, which means pumpkin spice lattes when it’s still too hot, our football teams are terrible, and election season is essentially over. Well, let’s take a beat on that last one for a second. While it may be true that most of our races are decided in the Democratic primary, there’s a lot at stake in 2022 – from who occupies the Governor’s Mansion to what we value as a state.

Candidates aren’t the only thing on the ballot this year. Who you vote for will decide whether hard-fought criminal justice reforms will be rolled back (further), whether the legalization of marijuana will be truly equitable, and so much more. Many might not realize that $4 billion is sitting on the back of their ballots, potential environmental funding that could go to improving over-polluted Black, Latino, and Asian neighborhoods.

So, what’s the plan? That’s the $220 billion question (and the size of the state budget). The proven plan of action to make sure New York State crosses the threshold of change is to organize. Communities of color have a powerful vote we must make sure is exercised during one of the most important November elections this state has seen in decades.

Here are three things you can do this fall to make change happen in your neighborhood and beyond:

First, get off social media and talk to your neighbors. Figure out what issues are important to them. If you live in Southeast Queens, you might be surprised by how many people want property tax reforms, which is one place the state races come in. Your neighbors in public housing may have been fighting to repair a senior center, which every level of government bears responsibility for (and don’t let officials tell you otherwise). Read up on the back-of-the-ballot measures and be ready to spread the word — most people don’t realize they have a say on these major policy decisions.

Second, find the people who are running and push them to make real commitments on issues of importance that you organize around. The key here is to make sure they hear the same message over and over and over again. It’s essential that your community speaks as one voice, which I know is easier said than done considering even the friendliest of neighbors have their differences.

As an organizer I’ve found the best path is to focus on what unites us – the change that can positively impact the most people – while also acknowledging and validating those differences. Find your local civic organizations, faith leaders, and other recognizable community members who can bring everyone together, especially by speaking publicly on these issues.

Third, above all else, go vote. I don’t want to hear that it’s November, it’s chilly, you had a bad day at work, or it’s dark early. In New York, you can still vote by mail due to the pandemic. There are also nine days of early voting. Your Election Day poll site is likely on your way to or home from work (and not that far from home if you work from home). There’s no excuse not to vote anymore. Cynics be damned: change starts at the ballot box the more people vote. In fact, challenge two friends to go vote and make sure they each get two more people to go. The only way to show the power of a community is with that all-too-powerful right to vote.

These steps might seem overly simple, but sadly they’re too often forgotten. We take this kind of work for granted, only to complain when our leaders fail us or there isn’t any accountability for matters like racial injustice. It’s what lost elections and influenced how districts are drawn up. This fall let’s get back to basics, back to engaging our neighbors, and back to the polls.

***

Paul Persaud is a Vice President at Actum, a global consulting firm, where he specializes in third-party organizing. On Twitter @Actum.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Recharge NYC Climate Policies; City Government Must Finally Transition to Zero-Emission Vehicles

Electric vehicle charging (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

It’s Climate Week but you don’t need to be an environmental expert to see the devastation and daily effect that fossil-fuel driven climate change has on our communities.

Whether it’s the oppressive heat waves rolling over our cities, families being washed away by deadly flash floods, or any of the other extreme weather events we have to contend with now as part of our day-to-day lives, the immediate and irreparable impact of the quickening pace of climate change is all around us.

This scary scenario begs the question, what are we doing about it? Unfortunately, the answer is not nearly enough and not fast enough. Aside from failing to achieve a decrease in carbon emissions, we are nowhere close to reaching steady-state emissions goals and clearly losing the battle to even stop annual increases in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions with the CO2 global average reaching another record high in 2021 at 415 parts per million (ppm).

Last year New York City committed to having a fleet of zero-emission vehicles by 2035. This effort would help the City actually reach its climate goals, reduce toxic air pollution that disproportionately harms communities of color where child asthma rates are well above the citywide average, and, as an added bonus, strengthen the city’s economy with new construction and renewable energy infrastructure jobs.

But this “commitment” alone isn’t enough. New City Council legislation – “Zero Emission Vehicles for NYC” – would greatly accelerate the city’s adoption of zero-emission vehicles. Instead of city agencies continuing to buy or lease traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles for years to come, we can fast-track the purchase of zero-emission vehicles that will allow us to finally set a course towards meaningful climate goals.

In 2019, New York City passed the Climate Mobilization Act, the most ambitious legislation in the country to reduce building emissions. Emissions from stationary sources, which are mostly buildings, accounted for 70% of New York City’s emissions in 2020. The second biggest source of emissions is transportation: 25% of emissions. New York City’s lack of progress in addressing transportation emissions is deeply troubling. It has the largest municipal fleet in the country, approximately 30,000 vehicles, yet it has purchased or leased fewer than 750 light-duty battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and has not deployed significant numbers of medium-duty or heavy-duty BEVs. However, zero-emission choices exist in all relevant vehicle types, including general purpose vehicles, ambulances, fire trucks, pursuit-rated police vehicles, sanitation trucks, school buses, and street sweepers.

The new bill would require New York City to purchase or lease only zero-emission light-duty and medium-duty vehicles beginning July 1, 2025; and heavy-duty and specialized motor vehicles beginning July 1, 2030; and require the city’s entire fleet be converted to zero-emission vehicles by July 1, 2035.

Transitioning the New York City government fleet to zero-emission vehicles is a critical step towards safeguarding the health of New Yorkers, especially those who live in environmental justice communities that have historically borne the brunt of environmental racism, including disproportionate pollution burden. For example, Bronx residents are besieged by the air around them, particulate matter levels two-and-a-half times higher than the state average, and in the South Bronx, children and teenagers visit emergency rooms with asthma-related illness at rates twice the city average, and nearly 20 times the frequency of neighborhoods with the lowest rates. Tackling emissions by reshaping the city fleet is a critical first step towards fixing this injustice.

States and cities that take real action will experience the most job creation as the world transitions from oil to electricity. New York businesses and consumers spend over $20 billion each year on gasoline and diesel fuel produced in other states and countries. As electricity is substituted for oil, this money will increasingly stay in-state, creating livable wage jobs in renewable energy production, both at utilities and in construction. The bill will accelerate this state-wide trend and also strengthen the prospects of New York City-based mobility and energy infrastructure firms such as Charge Enterprises, Gravity, Ideanomics, NineDot Energy, REV Renewables, Revel Transit, Tarform Motorcycles, and others.

While many city government leaders have expressed support for emissions reduction policies, good intentions alone do not result in meaningful action. It is clear we need to speed up our clean energy efforts if we are serious about addressing the climate catastrophe facing us.

This new bill will do just that, expediting progress while also offering smart flexibility in making the transition to zero-emission vehicles achievable. Communities on the frontlines of climate change and at the epicenter of the devastating impacts of the fossil fuel economy simply cannot afford any more delays and inadequate measures.

***

Wayne Arden is Sierra Club NYC Transportation Chair. Arif Ullah is Executive Director of South Bronx Unite. On Twitter @scnycgroup & @SouthBronxUnite.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Long Island is Becoming a Clean Energy Hub to Replicate Across the Northeast and Beyond

The Calverton Solar Energy Center, Riverhead, NY (photo: National Grid)

This week, thousands of leaders are in New York for Climate Week 2022. While the presentations and networking are happening in New York City, the action is taking place to the east on Long Island.

As more clean energy solutions like offshore wind, solar, battery storage, and clean hydrogen surface, Long Island is quickly emerging as a clean energy hub. Applying the solutions that are working here to other communities throughout the Northeast will be critical to mitigating climate change while continuing to provide reliable, affordable energy to residents that call this region home.

The key to Long Island’s success as a clean energy hub is a hybrid approach to decarbonization that incorporates multiple sources of renewable electricity and heat.

In Riverhead, the 23-megawatt Calverton Solar Energy Center powers more than 4,200 homes. This reduces carbon emissions 20,000 metric tons per year – equivalent to removing 4,000 cars from the road. In addition, the waters surrounding the island will soon be home to offshore wind projects including the South Fork Wind Farm and Community Offshore Wind, a joint venture between National Grid and RWE that has the potential to host 3 gigawatts of capacity – enough to power more than one million homes. To ensure consistent power supply, regardless of the weather, National Grid and NextEra Energy Resources have built 80 megawatt-hours of battery storage in Montauk and East Hampton, which is crucial for ensuring reliable service when it is not windy or sunny.

Alongside these traditional sources of renewable energy, Long Island is also embracing cleaner fuels that can replace natural gas to provide clean heat. Renewable natural gas (RNG) and clean hydrogen can be used in the same way as natural gas, but are significantly better for the environment. Clean hydrogen is a nearly emissions-free alternative to fossil fuels produced by separating hydrogen out of the water molecule, leaving only water vapor behind.

Hempstead will soon be home to one of the first hydrogen blending projects in the nation, using existing wind and solar equipment to create clean hydrogen to provide heat. Existing power plants fueled by oil and gas on Long Island can also be replaced or converted to run on clean hydrogen instead of fossil fuels.

Together, these initiatives put Long Island on the path to becoming a clean energy hub that can serve as an example for communities in the Northeast and throughout the country. It helps that Long Island sits in New York state, which has one of the most ambitious clean energy agendas in the country and a goal that 70% of the state’s electricity will be fueled by renewables by 2030. However, a number of states in the Northeast are equally ambitious. Imagine the progress we could make on addressing climate change if the Long Island model became ubiquitous.

That is the long-term goal of National Grid’s new Northeast Clean Energy Vision. Building on the company’s recently-announced fossil-free plan, the Northeast Clean Energy Vision is a roadmap to establish the region as a leader in clean energy by developing a collection of large-scale hubs modeled after what is currently happening on Long Island.

Making this vision a reality across the Northeast will not be easy. Actions taken by New York state on infrastructure planning are critical to making meaningful, near-term progress. And the federal funding for projects that can mitigate climate change included in the Inflation Reduction Act is a huge boost, but we cannot stop there. We are now looking ahead to U.S. Senator Joe Manchin’s permitting bill that will ensure expedited siting approvals for clean energy projects. Additionally, we will need to strengthen our focus on putting communities first in the energy transition; one great example is workforce development programs.

The clean energy hub on Long Island is a great example of what is possible when industry and government work together to fight climate change. The technology choices are clear, but we need to continue to develop the right policies and the leadership to implement them.

***

Will Hazelip is President of National Grid Ventures, US Northeast. On Twitter @nationalgridus.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.