Reimagine Alumni Support So It Works for All Students

Students at school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

I was a kid from Harlem, a first generation immigrant, and the first in my family to graduate from college – the U.S. education system was not built for kids like me to succeed.

Thankfully, along the way, I got the support I needed to excel and live out the dreams that my parents had for me as well as the aspirations I had for myself. Sadly, that is not the reality for countless kids from underserved communities just like me. But it can be, if we start to reimagine the support systems around them.

My parents left Ecuador with the hope that they could create a better future for their children, and they believed an American education was key to this. My father dreamed of having one of his children attend an Ivy League school. It felt out of reach, but all of that changed when my mom saw an advertisement for a new school in our neighborhood, and slowly but surely, their dream started to come true.

In 2005, my parents enrolled me as one of the first 100 students at KIPP Infinity Middle School in Harlem, a decision that changed my life. I stayed with the KIPP network of public charter schools through high school and then even more doors of opportunity were opened. During my time at KIPP, I traveled throughout New England to visit potential colleges, including Yale and Harvard, embarked on a 10-day excursion to Utah to hike Arches, Bryce, and Zion National Park, and visited China.

The world I knew expanded and I was influenced by these new environments. I got to experience new things, meet new people from all different backgrounds, and, perhaps most importantly, I got to work with a support system that knew how to prepare me to advocate for myself.

My advisors gave me the opportunity to identify my goals and the tools I needed to meet them. I learned how to prepare for college and succeed at the top schools. Before I knew it, I was opening my University of Pennsylvania acceptance letter in the mail on the auspicious date of 12/12/12.

But while I was learning and growing and taking advantage of every opportunity I could, other kids in my neighborhood were falling behind.

While I had college counselors helping me every step of the way – from applications to financial aid forms – most students do not.

KIPP Forward, the alumni support program that sticks with KIPP students once they graduate high school, helped guide me in college and helped me find a job post-graduation through peer and employer networking events, such as the KIPP Alumni Summit. For my friends who did not attend KIPP, any guidance many of my friends were receiving stopped the day they graduated high school.

The sad truth is: their experience is closer to the norm for students who look like me. For students of color, post-secondary preparedness programs are few and far between. In fact, Black and Latino students are inadequately enrolled in math courses and under-enrolled in Advanced Placement (AP) classes as compared to white peers.

These disparities continue through college, where students of color are significantly more likely than our white peers to drop out of post-secondary programming and education programs – creating a reality where white students at public colleges are 250% more likely to graduate than Black students, and 60% more likely to graduate than Latino students.

We can – and must, end these disparities.

My experience shouldn’t be the exception – it must become the norm. Our education system must develop postsecondary and career readiness programming, alumni support, and networking opportunities for all students so that low-income students of color across the country have the tools they need to chart their paths for success.

I keep in touch with my counselor to this day. In college, he visited me to help with my transition and helped me find the right internship opportunities. After graduation, I leaned on him for networking and guidance in my career. And now, I collaborate with him through our work at our alumni association.

At KIPP Forward, we are helping to change what alumni support can and should look like because the status quo has not been working for students of color. Our program is unique, but it is also scalable for schools across the country.

The support system we offer – which prepared me for college, helped get me to college, succeed in college, and supported my career after college – should be available for all students. If schools across New York and beyond do the same, we can reimagine what alumni support means, and finally provide all students with the keys to success.

***

Kevin Hidalgo is Senior Financial Analyst at American Express, and a KIPP NYC alumnus.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Boost NYC’s Tech Sector to Ensure a Full Jobs Recovery and Stronger Future for New Yorkers

Mayor Adams sees tech jobs in action (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

It's now clear that predictions of economic doom for New York made in the early days of the pandemic were as far off as, well, forecasts of the city’s demise made after 9/11 and the Great Recession. But while there are numerous signs that the city is bouncing back strong—from an uptick in tourism to sky-high demand for apartments—New York still has a long way to go in its employment recovery. Indeed, the city still has 123,000 fewer jobs than it did in February 2020, regaining just 82% of the jobs lost in the pandemic (compared to 100% for the nation).

There are many things city policymakers can do to spark a more complete jobs recovery, but few are as likely to succeed as supporting the continued growth of the tech sector.

Tech has been a force in the city’s economy for well over a decade. But in recent years, the tech sector has reached another level, becoming New York’s single most important job engine, and the most reliable source of new well-paying jobs. In fact, the tech sector has accounted for a remarkable 17% of the city’s entire private sector job growth since 2010, growing seven times as fast as the city’s overall economy.

It’s also been creating loads of well-paying jobs at a time when the city’s more traditional sources of good jobs have seen much slower growth. While the tech sector added 114,000 jobs in the city over the past decade, the construction industry created 29,000 jobs, the film and tv sector 19,000, the securities industry 17,000, hospitals 4,000, and law firms 3,000. Manufacturing jobs in the city declined by 20,000.

The tech sector has also outpaced all other major industries during the pandemic, with employment in the sector increasing by 8.7% since February 2020, a period when overall private sector employment in the city declined by 5.3%.

Although some tech fields face headwinds today, many others are on the cusp of significant growth. As one sign of the enormous potential, the number of start-ups has increased by at least 35% in 37 different tech sub-sectors over the past 5 years—from artificial intelligence and e-learning to ‘women’s and family’ tech.

As much as New York needs this tech growth to continue, it is by no means a given. Indeed, New York is facing new challenges that emerged during the pandemic that could dampen the sector’s growth here.

For one, remote work has made it easier than ever for tech workers—and the companies that employ them— to locate wherever they want, making it increasingly important for New York to be a leader in quality-of-life issues. Moreover, just as workers are more mobile than ever, New York is facing growing competition from several other cities that—unlike ten years ago—now boast dynamic tech ecosystems of their own, as well as significantly more affordable real estate. The departure of several tech companies from San Francisco since the pandemic arrived is a cautionary tale.

New York can overcome these and other challenges. But it will require a level of support from city policymakers that matches the new economic importance of the tech sector.

Mayor Adams has already been an enthusiastic and supportive champion for New York’s tech sector. Other parts of city and state government will need to follow suit. The wrong economic development, regulatory, and legal policies could cause the city to miss out on the sector’s extraordinary potential for future job growth.

There are several specific steps city officials should take to keep the tech sector growing, but the three most important actions involve people:

First, prioritize investments in parks, transit, safety, culture, and affordability—all of which are key to retaining and attracting talent, the key to New York’s continued strength as a tech hub.

Second, ramp up investments that will greatly expand access to tech careers for New Yorkers, including new investments in computing education in the schools, scaling up the most effective tech training programs, and harnessing CUNY as a springboard into tech roles.

Third, position New York to become the best place in the nation to work from home. This might include investing in new pocket parks and open spaces in residential neighborhoods, bolstering high-speed Internet service, and eliminating barriers for property owners outside of Manhattan to convert first- or second-floor retail space into hubs for communal office work.

By taking these steps, New York can turbocharge the city’s jobs recovery and build a larger and more inclusive tech ecosystem for the long run.

***

Jonathan Bowles is Executive Director of the Center for an Urban Future. Jason Myles Clark is Executive Director of Tech:NYC. On Twitter @jbowlesnyc of @nycfuture and @jasonmylesclark of @TechNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

It's Time to Separate Housing from Politics

Housing (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

It’s time for New York to depoliticize housing.

Population growth across the five boroughs has so badly outpaced housing production over the last decade that the city needs more than half a million new units by 2030.

A new report by the nonpartisan Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) slammed the process through which the city decides to approve or reject the kinds of development projects that could supply that housing, calling it an “impediment to progress.”

Many of the flaws identified in the report stem from the political nature of that process. While housing is a citywide problem that involves complex issues of urban planning and economics, ultimate decision-making power on land use matters is delegated not to experts in those fields but to the local City Council member.

That is not a knock on these public servants. But the dynamic nonetheless makes real progress next to impossible. While the shortage of housing is a citywide crisis, individual development projects often are deeply unpopular among those who are most vocal and politically active. The fact is that elected officials answer to those who voted them into office, and while there have been examples of leaders making politically controversial decisions for the greater good – such as the SoHo/NoHo rezoning, supported by Council Members Carlina Rivera and Margaret Chin – it may be unreasonable to expect that to be the norm.

As a public relations consultant who has spent the better part of the last two decades helping developers engage communities, I understand the importance of seeking and incorporating input from stakeholders and earning their buy-in. That is something the current process incentivizes, and it can and should remain an integral part of any improved process moving forward. But that said, the status quo simply is not working for the hundreds of thousands of families, seniors, and young people who are homeless, rent-burdened, or unable to stay in their neighborhoods. Nor is it working for those who want to move to New York City from other states and countries to pursue their dreams – like millions have in the past – but cannot find affordable homes.

The CBC report offers as a potential solution allowing land use applicants to “appeal City Council rejections back to the [City Planning Commission] or to another body that represents citywide interests.” Delegating decision-making power on something as important as housing to subject matter experts with a citywide view is a sensible idea that should be explored further.

Another potential model is Connecticut’s 8-30g, a statute that fosters the development of housing by allowing projects in communities that have little existing affordable housing to bypass zoning restrictions if they set aside a percentage of units as affordable. The law puts the burden on local officials to demonstrate that an affordable housing project poses a threat to public health, safety, or quality of life. This has led to a number of projects in recent years that have moved forward in spite of the kind of limited but loud public pushback that has killed similar efforts in New York City – in addition to encouraging communities to proactively find ways to add affordable housing.

Whatever the path forward, doing nothing is not sustainable. Elected officials know their communities, and ought to continue to play a role in shaping development projects. But it’s time to stop putting them in a position where they are all but guaranteed to pay a steep political price for acting in the best interest of their constituents and the city. Let’s admit that politics are part of the housing problem and find a solution that takes politics out of the equation.

***

Tom Corsillo is senior vice president and head of land use at Marino. On Twitter @tomcorsillo & @marinopr.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Adaptive Reuse of Vacant Retail Can Build Better Neighborhoods

Closed storefronts (photo: Office of Manhattan Borough President)

Occupied storefronts in New York City make neighborhoods lively, convenient, and livable. But there is a big difference between thriving retail and retail vacancy. When metal grilles and empty spaces dominate, ground-floor retail becomes a community and citywide liability. Vacant stores are ugly, make people feel less safe, attract graffiti, and fail to offer needed neighborhood services.

Even before the pandemic, many neighborhoods were blighted by excessive rates of vacancy, much of it driven by unrealistic rent levels as landlords held out for a bigger payday. In 2019, there were 5,313 reported ground-level vacancies in Manhattan, which roughly equate to 31.2 million square feet of space.

The pandemic, the shift to work-from-home for many employees, and the dominance of online ordering have since generated an even greater retail collapse and rising vacancy crisis. The spreading ugliness stands in the way of a full recovery, including both traditional business districts and many mixed-use residential neighborhoods.

Mayor Adams and many civic and business leaders are concerned about this growing retail blight but have so far offered few solutions beyond encouraging employers to force workers back into Manhattan offices. But with many chain retailers and small food retailers shuttered, returning to work and socializing on coffee and lunch breaks has become even less attractive in office districts. Attracting substantial new retail back to many other neighborhoods also remains challenging given stubbornly high unemployment, high rents, and cheaper online shopping options.

A team of architects (Michael Meredith, Hilary Sample, and their studio MOS) have explored retail vacancy in their book Vacant Spaces NY (New York: ACTAR, 2020), and discovered many high-impact opportunities for adaptive reuse.

They have demonstrated that rethinking retail in Manhattan neighborhoods, where available housing is typically limited, represents a great opportunity for both neighborhood reinvestment and quality housing. Rethinking retail is a worthwhile addition to Mayor Adams’ "City of Yes" planning initiative that calls for eliminating "obstacles to repurposing space, allowing the city’s businesses and economy to evolve over time."

A conservative estimate of retail vacancies reveals that converted retail spaces in Manhattan alone could easily provide housing for over 125,000 residents (about 100,000 micro units or 35,000 two-bedrooms, for example). Further study is needed to determine specific scenarios, but the city and state need to think about incentives for conversion of retail space into desperately needed housing resources.

Affordable live/work opportunities abound in vacant retail, providing opportunities for studios and for stores in front and housing in back. Larger commercial spaces can be subdivided and redesigned for supportive or even market-rate housing, particularly in areas where ground floor retail has no upper stories (thus providing opportunities for courtyards to add light and air to apartments).

Vacant retail can also be turned into high-value community spaces including libraries, senior centers, cooling centers, childcare services, after-school programs, and community centers. Overcrowded schools could use retail space as annexes for student activities including libraries, art studios, and vocational training. The city could develop secure public bike parking, rented at an hourly rate, for the growing legions of bike commuters. Many empty stores could be rented and redesigned as the location of new public restrooms city leaders are advocating. Branches of city agencies could be set up in some retail spaces close to where people live and work, including Health + Hospitals neighborhood clinics.

We acknowledge that there are challenges to adaptive reuse. The process for a change of use would need to be made easier to obtain in the case of owner-occupied use (zoning and Department of Buildings applications). For residential space, some flexibility in the building codes might be required to make retail spaces work for housing. Adaptive reuse of ground-floor retail is nevertheless far less daunting compared to converting traditional office buildings to affordable housing.

The smaller scale of individual retail conversion projects and the flexibility possible for different uses opens a world of civic possibilities.

***

Hilary Sample is the IDC Professor of Housing Design at Columbia University (GSAPP) and Co-Founder of the New York-based architecture and design studio MOS. Nicholas Dagen Bloom is Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College and author of many books on housing and planning.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How We’re Fighting Age Discrimination in the New York City Workforce

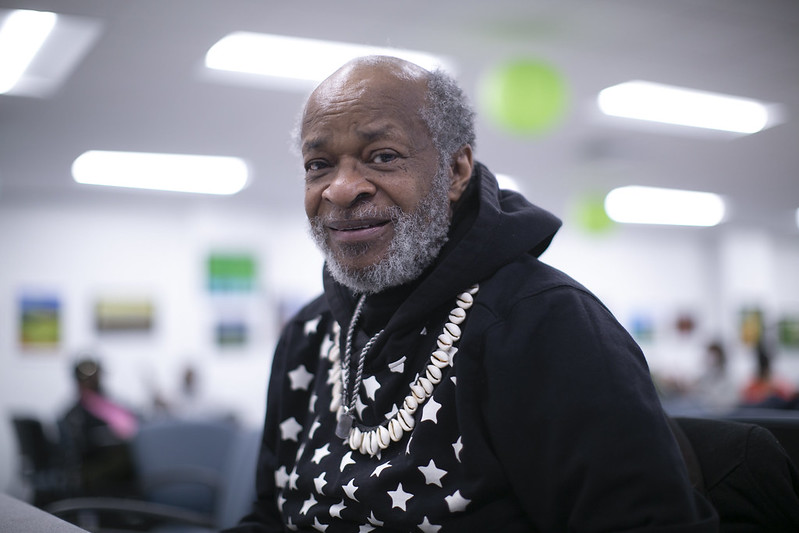

A New Yorker (photo: William Alatriste/NYC Council Media Unit)

Even with many of us working from home during the global pandemic, age discrimination was just as common in the workplace, and based on accounts from older adults, it has since grown even more rampant.

Earlier this year AARP found that 80% of older workers have experienced or seen some form of age discrimination, the highest reported number since the survey began ten years ago. It was also found that between March and April of 2020, the unemployment rate for those 65 and older quadrupled from 3.7% to 15.6%. This pattern can only suggest one thing: older workers have not been given a fair opportunity to show their worth.

Ageism is one of the least-discussed forms of discrimination our society faces and one we must speak out against. As we live longer, there are many individuals that, whether out of necessity or preference, will be working longer, and they must be treated just as fairly as their younger co-workers.

Since the 1980s there has been an increase in the number of men and women over 65 in the workforce. In fact, the only employed age group expected to grow by 2030 are those 75 and older. As these individuals become even more common in offices and other workplaces, there are many ways the private sector can make their establishments more equitable places to work. But unfortunately, workers begin to experience ageism in their forties. By not giving workers of every age group — in addition to gender and culture — an opportunity to succeed, these businesses will lose out on ample opportunities.

Studies have shown that businesses with a diverse workforce reach goals their competitors only talk about, including: retaining talent, because by ensuring all their employees feel a part of the team they are happier and more productive; innovating, because businesses with diverse staff reduce groupthink; reputation and profit growth, because when people see a diverse group working together, they like the company more and want to support it.

You do not have to look hard for an example of how to create more inclusive policies either, because the New York City Department for the Aging’s Older Adult Employment Services has been helping to make offices in New York more age-inclusive for decades.

For residents 55 years and older who meet income eligibility requirements, the Department for the Aging’s (DFTA) Community Service Employment Program helps individuals develop skills so they can have an immediate impact within the organization they work for. DFTA also has the ReServe Program, which matches participants with part-time opportunities at New York City agencies, where their background in several sectors including law, marketing, health care, education, and finance, allows them to mentor their co-workers who benefit from their knowledge.

This year, DFTA’s Office of Public-Private Partnerships continued its Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) combating ageism strategy and invited sister agencies to join online conversations focused on Building an Age Inclusive NYC. By adopting the DEI approach, city agencies not only create a culture of change internally, but they also influence the thousands of providers and vendors they work with. The most recent online sessions we conducted drew an average of 128 attendees, all representing DEI, Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO), and Agency Professional (APO) leadership.

These services were recently expanded with the new Silver Stars program, which gives retired civil service workers an opportunity to work part time at a city agency. This allows these retirees to continue contributing to the well-being of the city, while a new generation of civil servants benefit from their institutional knowledge, so they can troubleshoot problems and deliver services to residents, helping to create the next generation of talent New York will need going forward.

As more city agencies adopt age-inclusive policies, the organizations they work with can see how it is done, so they can replicate them in their offices, creating better cultures in thousands of businesses, nonprofits, and other organizations in every borough.

The fact is employers enjoy having older workers on their payrolls because they are the ones who stay at their jobs longer and take fewer days off. This is in addition to the strong work ethic they bring with them every day to the team they work with.

Creating these types of environments will not be as hard as employers think either. Why? Because both older and younger workers appreciate each other’s skills.

Fostering collaboration between older and younger employees breaks down the stereotypes older workers continue to face. It will also make the employer stronger and in turn create an even more equitable city we can all be proud to live in.

***

Lorraine Cortés-Vázquez is Commissioner of the New York City Department for the Aging. On Twitter @NYCAgingCmmr & @nycseniors.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

In a ‘City of Yes,’ We Can’t Say No to Land Use Equity

Mayor Adams talks housing (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

In the spring, the Adams administration announced “City of Yes,” a package of citywide zoning text amendments that ostensibly aim to advance affordable housing, jobs, and sustainability. ANHD applauds the recognition that a citywide approach is needed to combat our discoordinated land-use efforts.

But in a city driven by for-profit developers and powered by long-standing systems of racism and disparity, it will take an intentional approach to ensure we don’t continue to say “no” to land use equity. Instead, this administration must make New York a “City of Yes” for the land use needs and wants of our marginalized communities.

In the battle over land use in New York City there’s a growing push to label any community opposition to a given development as NIMBY (not in my back yard). This narrative is vastly over-simplified. It ignores the reality on the ground and the long-standing and ongoing power imbalances between communities.

It’s true that in the past several years we’ve seen neighborhoods reject a wide array of projects, from luxury housing to affordable housing to homeless shelters, infrastructure improvements to school construction. But to treat all this opposition as the same is not just wrong, it’s harmful. To paint all community opposition in the broad strokes of NIMBYism is to actively disempower and minimize the voices of low- and moderate-income communities of color and immigrant communities.

It’s essential to recognize the difference in why certain communities say no to land use and development proposals. There’s a fundamental difference, for example, between primarily white residents of Throggs Neck saying no to a rezoning that would bring affordable housing to a low-density section of the neighborhood versus immigrant residents and residents of color in Astoria saying no to a predominantly luxury housing rezoning like Innovation Queens.

It’s the difference between saying we don’t want any affordable housing in order to preserve our neighborhood character and saying we want more affordable housing in the quantity and depth of affordability that truly serve our community instead of displacing it.

It’s a recognition of the differences between neighborhoods and an understanding that in communities with higher displacement concerns a new residential unit is not necessarily a positive if it’s out of reach of local residents. The way to provide affordable housing in those communities is not to rely on a trickle-down housing approach that provides primarily unaffordable, market-rate units. If, despite this nuance, the mayoral administration takes the line that it will say yes to all proposals, and more specifically, that it will dismiss all nos, it will actively deny the empowerment and voices of low-income communities of color.

New York City cannot continue the mistakes of previous administrations. The answer is not to try to suppress or work around community engagement, input and decision-making, or further retreat from transparency and accountability. The answer is for this administration to be a trailblazer for equitable planning: with the central goal of empowering New York City’s marginalized communities.

The answer is to chart a course for planning that prioritizes the critical interests of those communities with the greatest need for affordable housing, good paying jobs, and long overdue capital investments, while facing the greatest risk of displacement and discrimination. The answer is to be intentional about whose voices and needs we’re centering in our land use process and to commit to an approach that puts their inclusion and power front and center.

The “City of Yes” is a critical opportunity for the Adams administration to lead equitable planning, by working in partnership with marginalized communities from the beginning. ANHD hopes this administration, unlike its predecessors, will hold robust community engagement and discussion, with a true opportunity for input and influence before any citywide zoning amendments are officially introduced. Not as an invitation for bad-faith actors to push policies of exclusion and displacement. But to ensure that those who have been harmed and disregarded by the zoning status quo are listened to and empowered, so we can finally begin to move towards the equitable planning outcomes we all claim to seek, and New York City deserves.

***

Barika Williams is the Executive Director of ANHD. On Twitter @barikaXw & @ANHDNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Black LGBTQ Leaders to the Front of the Line

Sean Ebony Coleman, the author (second from left)

Visibility for the LGBTQ community is at an all-time high. Though this heightened exposure can lead to progress, there are also drawbacks – particularly when it comes to accurate representation of intersectional identities. When you think of LGBTQ leaders, who comes to mind? How many of them are Black?

It is important that, in addition to prominent white LGBTQ figures, the wider public is just as conscious of Black LGBTQ thought leaders who have the necessary lived experience to have exhaustive, informed discussions about various issues. To accurately represent and support the community when it comes to politics or public policy, we need to be strategic in appointing Black LGBTQ leaders to ensure they have a seat at the table.

While in the past few years some progress has been made for Black LGBTQ figures, many are still idolizing and positioning white LGBTQ folks as spokespeople for the entire community. This paints an inaccurate and harmful picture.

While it is demonstrably false, the misperception that the LGBTQ community has made more advancements than the Black community is very prevalent, particularly among Black people. The notion negates the intersection of being Black and LGBTQ, and the disparities that exist – disparities that are exacerbated when these two identities collide.

I understand where this image comes from – we picture a LGTBQ individual, perhaps a white gay man, who is celebrating Pride, enjoys equal rights to his straight counterparts in several areas around the country, and seems to live in abundance. This image, especially during June’s Pride Month, makes many in the Black community feel left behind as they watch another marginalized community advance and seemingly bypass them. While we have to be careful to not participate in the ‘Oppression Olympics,’ we have to have an open discussion about this reality.

To achieve legitimate and sustainable progress for Black and brown LGBTQ individuals, we need to uplift LGBTQ leaders who represent and embody the diversity and lived experiences of those who identify within the community. As a result of the over-representation of white gay cisgendered men and women as the leaders, outside perspectives are skewed and don’t recognize the many intersectionalities of identities. The failure to include Black and brown folks who are trans and gender non-conforming further perpetuates the silencing of these communities, who also face higher rates of violence being directed towards them.

The average life expectancy of a Black trans woman is 35 years. In 2021, at least 51 Black transgender people lost their lives to violence, which makes it the deadliest year on record. The average income for a Black trans person is $10,000, making it almost impossible to secure safe, affordable housing. Juxtapose this with the lack of visibility and stigma that still exist within the Black community around all things LGBTQ and we begin to see the full picture. Black trans/GNC folks play a vital role in representing the community and deserve a platform to educate others and denounce perceptions surrounding their existence. Creating safe space for Black LGBTQ individuals to share their legitimate lived experiences is a non-negotiable step towards progress. This is why I founded the Bronx LGBTQ center, Destination Tomorrow – Black and brown community members deserve to have a safe space right in their own neighborhood.

Black LGBTQ folks are in need of an organizing effort for our community to address the continued disparities. Many other minority groups have made progress towards eliminating issues facing their communities by directly addressing them through policy and political actions.

Throughout the pandemic we have seen heightened acts of racism and targeted attacks against the AAPI community, specifically against AAPI women. In response, the Stop Asian Hate movement was created to combat this violence – The New York City Commission on Human Rights, the Mayor's Office for the Prevention of Hate Crimes, the Mayor's Community Affairs Unit (CAU), and the Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs all began to coordinate closely to educate the public about their rights and protections in light of COVID-19-related stigma and hate crimes.

Moments like Stop Asian Hate help create a vision of what is possible for the safety of Black LGBTQ communities. With the proper organization and support, the creation of spaces to educate Black young LGBTQ folks around the issues that impact their lives is possible, but to this day these efforts are severely underfunded and disregarded.

We must hold other communities accountable and speak up at the table where we’re not represented. Calling attention to these issues and creating space for representation is the only way to change the dynamics of the conversation. White allies and LGBTQ individuals with more privilege must act to elevate the voices of those who are not being heard and fall victim to transphobia, homophobia, and racism.

***

Sean Ebony Coleman is the founder and executive director of LGBTQ+ organization Destination Tomorrow and a longtime activist for transgender/gender-nonconforming rights. On Twitter @Dest2morrow.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Forgotten History of Latino Politics in New York: Part II

Felipe Torres (photo: Center for Puerto Rican Studies, CUNY)

This is the second part of a series on the forgotten history of Latino politics in New York; read part one here.

The Republican Party during the pre-FDR era was surely not the GOP of today, in New York and beyond. This is made clear by who the Republicans chose as their candidate for State Assembly in what was then considered “South Harlem.”

Oscar García Rivera was by no means a Republican as we understand the term today; he had not a single conservative bone in his body. In fact, Garcia Rivera was a true progressive through and through. For supporters like the cigar-makers (see part one of this column), it was easy to rally behind one of their own, for he was not only a Puerto Rican, he was also a socialist.

As is typical of any winning campaign, especially one looking to unseat an incumbent, García Rivera’s victory in 1937 was a result of a confluence of support from leaders and organizations and the right political climate—a climate that increasingly demanded broader representation.

On one hand, after a decade of ardent struggle for representation in which the number of Puerto Ricans in New York continued to rise, nationalist fervor among Puerto Ricans in Gotham was palpable by the time García Rivera sought the Assembly seat in East Harlem. On the other hand, long-standing progressives saw an opportunity to elect someone who aligned with their progressive values. Thus, staunch Marxists, labor activists, the American Labor Party, and the city’s Fusion Party, together with the burgeoning Puerto Rican electorate and a Republican Party looking to defeat a Democrat, were part of a grand coalition that made possible the election of the first Latino in New York.

The prospect of electing “one of their own” was widespread among Puerto Ricans, even in areas outside of East Harlem. La Prensa, one of the first Spanish-language dailies in New York (La Prensa would merge with El Diario de Nueva York to form El Diario/La Prensa in 1963), wrote several articles on García Rivera’s campaign. One such article comes across as rather mundane—“Aumenta el interés en la campaña en el Distrito No. 17.” The piece highlights a “gran mitin” (a great meeting) that brought together the coalition rallying around García Rivera. Even the Spanish-language reporters, who perhaps in this instance relinquished some impartiality, could not contain their glee at the possibility of electing the first Puerto Rican not only in New York but also in the continental United States.

However, García Rivera’s appealing candidacy was a threat to the powers of the time and was met with strong opposition, most notably from the powerful Tammany Hall machine. Their candidate was the incumbent, Meyer Alterman, a Democrat who was also the chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee in the Assembly. One of the Spanish-language dailies reported on some of Tammany Hall's typical shenanigans, including fraudulent voter registrations in order to cast illegal votes.

Responding to one of the Spanish-language dailies’ inquiry into an increase in voter registration ahead of the election, García Rivera himself noted that Tammany Hall Democrats via the Wichita and Owasco Democratic clubs, made a concerted effort to hamper Latino voter registration by providing false information to eligible Puerto Rican voters. In some cases, these Tammany Hall loyalists told Puerto Ricans that they were obligated to take a first-time voter exam in Brooklyn, when this was not the case. In other cases, Tammany Hall made sure to fraudulently pad voter rolls by registering non-Latino individuals in specific Latino households. By García Rivera’s own estimates, out of a total of 6,000 newly-registered voters ahead of the election, at least 2,000 were fraudulent registrants.

It was clear that Tammany Hall would use all their influence, including strong-handed and illegal tactics to deter the first Latino from winning a seat in the Assembly.

Yet, demographic destiny was on García Rivera’s side. Coupled with the support of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who ran on the same ticket as Thomas Dewey in his 1937 race for district attorney, and the fierce support of labor leaders like David Dubinsky, Alex Rose, and Mike Quill, García Rivera would go on to defeat the incumbent by more than 1,500 votes in an election that saw 17,807 voters go to the polls.

García Rivera understood right away that his historic election was in part a result of the people’s desire for a change from the conventional political misconduct. He was not, and never would be, indebted to Tammany Hall Democrats. His allegiance was to the people and the people alone.

East Harlem was also a community in great need—East Harlemites clamored for political leadership that would fight to alleviate the ills plaguing it, from rampant poverty to a housing affordability crisis. They hoped García Rivera would do his part in the Assembly. And that he did.

When asked by La Prensa’s Antulio Rodriguez Castillo what legislative agenda he would take to Albany, García Rivera responded straight-forwardly, clearly showing that the progressive philosophy he ran on was not mere rhetoric, but rather stemmed from a deep belief that a progressive agenda was exactly what would benefit the poor of East Harlem.

García Rivera’s first order of business was to introduce an affordable housing bill that aimed to restrict the ability of landlords to raise rents arbitrarily. It is rather ironic that 85 years after García Rivera’s election, East Harlem and indeed the city as whole face a major housing affordability crisis (and there is fierce debate over a bill in Albany that would cap rent increases).

García Rivera also sought to root out the corruption prevalent in city politics, which he felt contributed to the crises plaguing areas like East Harlem. Perhaps his idealistic views about what good government could do were balanced with some political realism—taking on corruption in government would continue to help weaken an already declining Tammany Hall, which would surely help his re-election efforts.

García Rivera promised to work with Mayor La Guardia’s administration and newly-elected Manhattan District Attorney Dewey, to root out corruption in government. According to García Rivera, Dewey, who would later become governor and the Republican nominee for president in 1948, promised to work with him on such efforts. It could be said that Dewey lived up to his promises since he went on to prosecute Tammany Hall boss James Joseph Hines on racketeering charges.

García Rivera was successfully re-elected in 1938. His second winning political campaign was not just a result of the debilitation of Tammany Hall; García Rivera also had a solid record to run on.

In just one year, he introduced a number of bills supported by progressives. More importantly, these bills were seen as a powerful message to the people of East Harlem that their community finally had an elected leader that prioritized their needs and not those of Tammany Hall. García Rivera introduced an anti-discrimination bill that would fine employers for refusing to pay workers because of race. In 1938 he introduced a civil rights bill (almost 30 years before the passage of the 1965 federal Voting Rights Act), and as promised, he introduced the aforementioned legislation that would limit the right of landlords to raise rents arbitrarily. In an address to residents in his community, García Rivera said the bill would be a “deterrent to greedy landlords” and would “protect the tenants in the low income bracket.”

With this record, García Rivera was ready for his re-election battle. This time, however, his enemies were not just limited to Tammany Hall Democrats. The Republican County organization, which had backed him just one year earlier, denied García Rivera the nomination in 1938 (Assembly elections were yearly then). The New York Times called it “an unusual political move.” García Rivera likened it to yet another Tammany Hall hit job.

Irvin Levy, the Republican leader in García Rivera’s district, told the Times that their support was rescinded because of García Rivera’s supposed closeness to communists. The GOP instead lent their support to a young African-American attorney by the name of John A. Ross. The Tammany Hall Democrats supported Meyer Alterman again, leaving García Rivera as the third-party candidate of the American Labor Party. Democrats and Republicans alike thought they had García Rivera’s number. The result was a nail-biter but García Rivera ended up victorious, besting Alterman by 235 votes.

Two years later, dynamics would shift drastically for García Rivera and the burgeoning East Harlem Puerto Rican community. Redistricting efforts significantly altered the 17th Assembly district and as a result, Democrat Hulan Jack beat García Rivera by 3,150 votes in 1940. García Rivera’s defeat also spelled temporary doom for Puerto Rican representation, as no Latinos were elected to any office for more than a decade.

Interestingly enough, during this void in Puerto Rican political representation a non-Puerto Rican, Congressman Vito Marcantonio, would go on to champion the cause of Puerto Ricans in New York and those on the Caribbean island.

The lack of Latino political representation after García Rivera’s defeat was not a reflection of any decline in the Latino population of New York. In fact, the very opposite was occurring. As the ‘40s gave way to the ‘50s, the growing number of Puerto Ricans in New York would increase by over 300%, from a little under 60,000 in 1940 when García Rivera was defeated to almost 300,000 by 1950. These New York City statistics in all likelihood underestimate the real picture of Puerto Rican migration at the time. By 1956, just six years later, an additional 300,000 Puerto Ricans had arrived in the city. (My parents were two of these 300,000; my father arrived in East Harlem in 1955 and my mother came to the same community in 1956.)

The continued rise of the Puerto Rican population meant that political machines could no longer bypass the need for Puerto Rican political representation. Much too large to ignore, the Puerto Rican population was ready to again elect one of its own.

In 1953, Felipe Torres, a 56-year-old attorney and graduate of Fordham Law School, was elected to the State Assembly, becoming the first Latino elected in the borough of the Bronx. Interestingly, the Torres family became prominent not only in political circles but also within the legal profession. After his stint in the Assembly, Felipe Torres was appointed a Family Court judge. His son Frank succeeded him in the Assembly and was also later appointed a judge. Felipe’s granddaughter, Analisa Torres is currently a federal judge, appointed by Barack Obama in 2013. (I was honored to help Analisa Torres in 1998 during her successful run for Civil Court judge in Manhattan.)

By the time Felipe Torres was elected, there were more Puerto Ricans in the Bronx than in East Harlem. Yet, East Harlem was the place that Puerto Rican political power would flourish first. In 1954, the last of the Tammany Hall bosses, Carmine DeSapio, appointed Tony Mendez as a district leader in East Harlem. Thus, Mendez became the first Latino Democratic district leader in New York history. Twenty-four years later, in 1978, his daughter-in-law Olga Mendez became the first Latina elected to a State Legislature in U.S. history. Tony Mendez founded the Caribe Democratic Club, which remains in existence today and is headed by an East Harlem community activist, Raul Reyes.

Mendez knew how to work DeSapio in order to increase Puerto Rican representation at all levels of government. Largely through Mendez’s efforts, Emilio Nunez, a member of his club, was elected to the City Court in 1956. Another Caribe Club member, Jose Ramos-Lopez was appointed to the Workmen’s Compensation Board. Manuel Gomez became deputy commissioner in the Magistrate’s Court. By the end of the decade, Ramos-Lopez was elected to the State Assembly, becoming the third Puerto Rican elected to the State legislature in New York history.

The advancement of Puerto Rican political power in East Harlem was a source of admiration for others around the city, particularly in the Bronx. However, East Harlem continued to get a bigger piece of the political pie, even though the Bronx constituted a larger portion of the Puerto Rican community in New York. Bronx political leaders called for greater representation, scorning their own political leaders, particularly Bronx Democratic boss Charles Buckley, for not doing more for the Puerto Rican community.

That would soon change in the 1960s when Herman Badillo entered the picture and became a political hero for Puerto Ricans in New York.

***

Eli Valentin is a political analyst and author of the forthcoming book, Reinhold Niebuhr: A Political Life. On Twitter @EliValentinNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Troubling Series of Uncertainties Mars Reopening of New York City Schools

Mayor Adams visits a school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

After two-and-a-half years of a chaos and disruptions due to the covid pandemic and a change in mayoral administrations, many parents, teachers, and advocates were yearning for a steadier, supportive, and safe re-opening of a new school year, in which students would get the attention and the stability they need. Sadly, that does not seem to be in store.

The pandemic is not over, no matter how much one may wish for it. The covid test positivity rate at 8.5% in New York City is still quite high, and while in general students appear less prone to the negative effects of the virus, the long-term impact of covid among children remains a serious concern. And even if not seriously ill themselves, they can still transmit the virus to their teachers or bring it home to their family members. Unlike previous years, this year’s covid safety protocols will be few.

Less than half of New York City children are fully vaccinated (at least two doses) against covid. There is no longer any mask mandate and no in-school screening for covid, no attempt at social distancing, and the air purifiers that the Department of Education purchased for schools are widely considered to be inferior. All this bodes poorly for the opportunity for children and their teachers to have a smooth and uninterrupted school year.

Another source of instability is the fact that Mayor Eric Adams is intent on making huge budget cuts to schools. Though initially the Department of Education claimed that the total reductions to schools would be $215 million, that turned out to be untrue. The City Comptroller has estimated that 77% of schools have suffered $469 million in cuts to the portion of their budgets allocated through the Fair Student Funding formula. Class Size Matters’ analysis of the schools’ entire budgets indicates that as of August 21, their total funding had been reduced by $1.3 billion, and projected that by the end of the school year, the total reduction would be about $1 billion compared to last year, as about $300 million was added after that date last year. A billion dollars is also the amount that has been slashed from the Department of Education’s entire budget.

After 45 out of 51 City Council members voted to approve the city budget late in the evening on June 13, many quickly came to regret their votes when they faced the anger of their constituents as the impact of these cuts on individual schools became clear. Many schools reported having to let go beloved teachers and social workers, others have been forced to eliminate art and music programs. Council members said they had been deceived by DOE officials, who had assured them that the budget cuts would have no impact on current staffing or programs but would only eliminate positions already unfilled. Chancellor Banks’ response was that the Council had failed to “ask all the questions that needed to be asked.” By the end of July, 700 teachers had been excessed from their schools, though since most still remained on the DOE payroll, it remains uncertain what actual budget savings this will produce.

On July 18, parents and teachers filed a lawsuit to try to block the cuts, pointing out that the City Council vote had preceded by ten days the vote on the budget by the Panel for Educational Policy, in violation of state law. While the DOE had claimed an “emergency” superseded the PEP vote, the plaintiffs pointed out there was no such emergency, and that the DOE had made the same claim with the same boilerplate language in 12 out of the last 13 years. They demanded that the Council have an opportunity to revote subsequent to the PEP vote in the proper order as specified by state law. Supreme Court Judge Lyle Frank ruled in favor of the plaintiffs on August 5, and ordered last year’s school budgets reinstated until the City Council had a chance for a revote. But the Adams administration appealed his decision, and the Appellate Court ordered an automatic “stay” on Judge Frank’s decision and the restoration of these cuts, at least until arguments in Appellate Court could be held, which are not scheduled until September 29 – long after the school year has begun.

Since their original vote to approve the budget, City Council members have organized rallies, held hearings, sent letters to the mayor, and now approved a resolution to demand that he immediately restore at least the $469 million cuts to schools. Yet Adams has not budged and continues to insist that these cuts are justified by a decline in enrollment. Meanwhile, he has been followed by protests nearly everywhere he goes, with parents and teachers insisting that he restore funding to their schools. He has told them to “keep us in your prayers.” In response, 135 religious leaders released a letter pointing out that the mayor’s comment was a form of “spiritual bypassing…rhetoric to avoid your responsibilities to the people of this city.”

One of the biggest wild cards amidst all these concerns remains the issue of class size. In early June, after years of advocacy by parents and teachers, the State Legislature overwhelming passed new legislation that would require the city to gradually lower class size in all grades, to achieve caps in five years of no more than 20 students in grades K-3 classes, 23 students in grades 4-8, and 25 students in high school -- levels closer to what class size averages are in the rest of the state.

The research is clear that such class sizes would provide students with a far better chance at success, in terms of achievement, graduation from high school, and a four-year college degree. Yet Governor Hochul has so far failed to sign the bill. Though she recently indicated that she was inclined to do so in the near future, she also signaled that she was in negotiations with Mayor Adams to propose amendments to the bill, which is worrisome as Adams has steadfastly opposed the measure, calling it an “unfunded mandate.”

As State Senator John Liu and others have pointed out, it is only right and just that the city should finally lower class sizes, given that the DOE is finally receiving the $1.3 billion in additional state aid resulting from the Campaign for Fiscal Equity case, in which students’ excessive class sizes were central to the court’s decision that they had been deprived of their right to a sound basic education. Yet after that decision was made, class sizes actually increased. It appears that the mayor would like to use the additional state funding, as well as nearly $4 billion in unspent federal covid education funds, for other purposes.

If nothing intervenes to stop him, his destabilizing cuts to school budgets will inevitably result in larger class sizes next year. What has been ignored in much of the controversy over the bill is how much students benefited last year because their schools were fully funded despite the enrollment decline, and principals were therefore able to keep their teachers and other critical personnel on staff, which in turn led to the smallest average class sizes in the city’s history.

Indeed, the Fair Student Funding formula that schools have relied upon since 2007 to pay for teacher salaries is fatally flawed, given how it has forced principals to keep class sizes excessively large – which in turn, has prevented students from receiving the adequate support that they deserve. Eighty percent of the principals surveyed in 2019 by a Fair Student Funding Taskforce said that large class sizes were a direct consequence of the formula.

Class Size Matters has heard from many parents and teachers who reported that along with the smaller classes last spring came a serene atmosphere, with the emotional sustenance that many children were lacking after two years of the pandemic. As one teacher put it, “All kids are needier than ever, whether simply needing attention and feedback from teachers or grappling with real trauma.”

As one principal announced, “What is devastating about the recent budget cuts is that 2021 felt like the first time in my 16 years in the DOE where we were getting close to being able to provide all kids with the supports and opportunities they deserved.”

Similarly, a parent of a middle school student reported, “This is the first year after being in NYC public schools for seven years that the teachers are able to provide individualized attention to my child’s social and emotional needs. Her teachers all know her really well for the first time.”

Yet rather than sustain and build on the progress enabled by smaller classes last year, Mayor Adams seems intent on reverting to the unacceptable conditions of the past.

Among the organizations that sent in memos of support for the state class size bill were the Alliance for Quality Education, the NAACP, NYC Kids PAC, the Network for Public Education, and the Chancellors Parent Advisory Council, which represents all the PTAs in the city. Nearly 9,500 parents and teachers have signed a petition urging Governor Hochul to sign the class size bill as soon as possible.

Parents hope that she will do so soon, without significantly weakening its provisions, so that the city’s children will be able to receive the close emotional and academic support that they have long deserved but need now more than ever before.

***

Leonie Haimson is the Executive Director of Class Size Matters. On Twitter @leoniehaimson & @ClassSizeMatter.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We Don’t Need a ‘Plan B,’ Mayor Adams; New York City Needs You to Shut Rikers Down

Mayor Adams at Rikers (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

As the crisis on Rikers Island continues and the death toll soars, Mayor Eric Adams told New Yorkers last week that there needs to be a “plan B” for the city’s plan to shutter the notorious jail complex, suggesting he may not close Rikers at all. This should alarm all New Yorkers who care about justice.

There is currently a plan in place to close Rikers by 2027 and drastically reduce the city’s capacity to jail people. In 2019 community groups secured a victory when the New York City Council passed and then-Mayor Bill de Blasio signed legislation to close Rikers and replace the existing borough-based jails. The plan dramatically reduces the number of jail cells citywide, while emphasizing diversion and alternative programs that promote public safety without relying on incarceration.

As a candidate, Mayor Adams committed to the Rikers closure plan. But as mayor he has done little to nothing to follow through, even outright ignoring the 2019 law, and has instead fought for policies to jail more people at Rikers, increasing the detention population, endangering lives, and further imperiling the closure plan. When the mayor said, “We need a plan B,” he went on to suggest expanding the city’s jail capacity by holding people – pretrial – in state prisons.

The Rikers closure plan requires the city’s detention capacity to be 3,300 or lower. But today about 5,700 people are in New York City jails—300 more people than when Adams took office in January, and thousands more than what is permissible under the 2019 plan, which purposefully cuts overall jail capacity.

Roughly 4,900 people (86%) are incarcerated pretrial. These people—neighbors, family, friends — are innocent until proven guilty, but most of them are in jail because they can’t afford bail. Having worked at a bail fund and posted bail more than 500 times in New York City, I know firsthand how immoral and predatory our state’s bail system continues to be — yes, even after the reforms that have been mischaracterized and partially rolled back twice.

Jail populations don’t rise on their own. They are the direct result of regressive decisions made for political gain.

Mayor Adams has made daily calls to roll back bail reform and incarcerate more New Yorkers pretrial—predominately Black and Latino people—due to unaffordable bail. And it’s working. The jail population is going up because Mayor Adams wants it to. This comes at a great cost, including the unacceptable reality that 13 people have died in New York’s jail system this year; the city is on track to surpass the grisly record set last year.

The mayor wants even more people behind bars at Rikers, where even more people will die.

And New York City taxpayers should not be spending more than $500,000 a year per person to hold people in cages on Rikers while cutting funding to schools and homeless services. This type of policy decision-making makes our city less safe.

To address the crisis at Rikers, there is no need for a “plan B” or for people to be sent to state prisons while they await their day in court. The solution is straightforward: utilize proven programs to reduce the jail population, invest in real community safety: housing, health care, education, and jobs, and shut down Rikers.

New Yorkers deserve better than a mayor who commits to one thing, does another, and seems to govern on the fly through reckless statements. People are suffering and dying, and the time for action—the time to close Rikers—is now.

***

Yonah Zeitz is the Director of Advocacy at the Katal Center for Equity, Health, and Justice. From 2017 to 2019 he was the Project Associate at the Bronx Freedom Fund. On Twitter @yonahzeitz & @katalcenter.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The City Council’s First Test to be The City of Yes We All Need

New housing (photo: @NYCHousing)

The housing market in New York City is more unaffordable than ever. How we got here may be complicated, including decades of zoning barriers to building affordable housing and insufficient overall production, but the way out is simple: every neighborhood must do its part to add to our affordable housing supply, without exception or delay. Rejecting the outdated attitude of “no” is the only way that we will ever overcome this challenge and create the city we deserve.

Mayor Eric Adams has rightly called for a “City That Says Yes” to infrastructure, jobs, and housing. That vision is facing its first test in the eastern Bronx in City Council District 13, where two projects will soon be debated before the Council, the first of which has a hearing on Wednesday. We cannot let the opportunity to say “yes” pass us by.

The first is a mixed-income project on Bruckner Boulevard, including affordable housing for seniors and veterans, and the second is an innovative supportive housing project led by the Fortune Society and NYC Health + Hospitals called Just Home that will provide housing and stability to formerly incarcerated New Yorkers with severe medical challenges on the Jacobi Hospital campus in Pelham Parkway.

Both proposals are in City Council District 13, presenting an opportunity to help fight the housing crisis in a district that has seen little affordable production. The data from our NYC Housing Tracker shows that more than half of District 13 residents are rent-burdened (which means they pay more than 30% of their income on housing), and 14.7% are living below the poverty level. Nearly 1,000 New Yorkers who were in a city shelter at the end of 2021 last lived in one of the two overlapping community boards. This district needs affordable housing as much as anywhere else in the city.

Despite the urgent need, District 13 produced just 58 units of new affordable housing in total over the last eight years – the fifth least among all 51 City Council districts.

Even still, the ugly face of NIMBYism continues to rear its head. A vocal minority of residents in Throggs Neck is fighting the affordable housing projects, shouting down advocates and even threatening them with garden hoses at rallies supporting affordable housing.

Communities should debate the specifics of individual projects, but it must be with the goal of getting to “yes,” for the good of people, communities, and the city as whole. We will never improve our housing crisis as a city by saying no to housing and telling vulnerable neighbors to pack up and find somewhere else to go.

Every neighborhood must say yes to more housing – including more affordable and supportive housing. When each neighborhood does its part of building more affordable housing, we will also be building a more equitable, livable city. In the past, more affordable housing has been built in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods; in the top third of districts in terms of affordable housing production, on average 72% of residents are Black or Latino, while in the bottom third of districts by housing production just 35% of residents are Black or Latino.

We cannot continue this trend. We need low-rise outer-borough neighborhoods that have continually opposed new affordable housing, supportive housing, emergency shelters, and other needed community infrastructure to also do their part.

In other words, we need to powerfully reject the NIMBYism and exclusionary zoning policies that have no place anywhere in New York City. No neighborhood can be allowed to simply opt out as they have in the past.

Throggs Neck may be the first test, but it will not be the last.

The entire metro area has a shortage of 772,000 apartments affordable to very low-income households, while nearly 1 million households are rent-burdened and more than 68,350 people were homeless in New York City, according to the most recent comprehensive estimate.

If we allow the reactionary forces in Throggs Neck to outnumber voices for positive change and growth, then those forces will be empowered everywhere – and the crisis will only get more distressing, year by year.

That is not the city that New Yorkers deserve. We must simply start making better choices – and that starts now, in Throggs Neck and then in every New York City neighborhood.

***

Rachel Fee is Executive Director of the New York Housing Conference. On Twitter @RachelFee4NY & @TheNYHC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.