Dark Streets

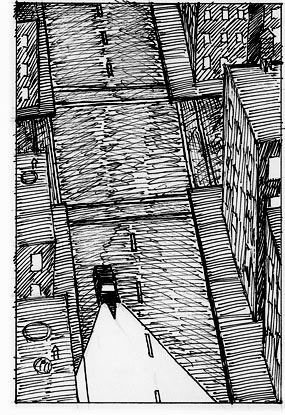

At a recent party, residents of the Ditmas Park neighborhood in Brooklyn shared their strategies for walking home from the Cortelyou Road subway station after dark. Some simply get off at the next station on the line. Some take circuitous routes, going out of their way to avoid one block of Marlborough Road. And a teenage boy talks to his parents on his cell phone until he gets to another block, hoping to quickly alert them to any problem.

At a recent party, residents of the Ditmas Park neighborhood in Brooklyn shared their strategies for walking home from the Cortelyou Road subway station after dark. Some simply get off at the next station on the line. Some take circuitous routes, going out of their way to avoid one block of Marlborough Road. And a teenage boy talks to his parents on his cell phone until he gets to another block, hoping to quickly alert them to any problem.

Marlborough Road between Cortelyou and Dorchester is not a hotbed of crime. But it is extremely dark.

The entire tree-lined block has only three street lights, compared to four on the next block. The block became more forbidding last year when a bar on the corner — whose feeble light spilled out a bit on the dim sidewalk — went out of business.

Most urban resident equate light streets with safer streets. Tourist guides and tips on how to live safely in the city advise people to avoid dark streets. Specific crimes, including the rape of the Central Park jogger, have been blamed on a lack of lighting.

Astronomers and sky gazing enthusiasts say that street lights make it difficult to see the night sky. They note that while in theory as many as 2,500 stars could be visible in a typical night sky, a person standing in midtown Manhattan is likely to see no more than 15. And lights can glare into apartments and homes, keeping people awake.

But the barriers to adequate lighting in New York are less likely to be concerns about light pollution than issues of cost, wiring and maintenance.

The Department of Transportation is responsible for installing and maintaining 325,000 New York City street lights. Its electric bill alone for the lights totals $50 million a year, according to department spokesperson Lisi de Bourbon.

The 311 city hot line handles complaints about broken street lights. A person can also file an on-line complaint form. The form lists more than 30 things that can go wrong with a street light from being burnt out to having exposed electric wires, shining in the wrong direction, or missing the door at the lamp post base.

People filing a complaint receive a work order number that enables them to check on the status of the job in the days ahead. The department says that its streetlight maintenance contractors must respond within 10 days of being notified of a problem. That does not mean, though, that the contractors have to repair the problem within that time. Instead, they can, for example, note that the job calls for a major repair — such reconstructions of the lamppost's concrete foundation — or refer the problem to Con Edison.

Complaints do get results. According to a recent article in the Bronx community newspaper the Norwood News students in a local middle school action club noticed that a number of street lights were out in the Williamsbridge Oval. "The lights are important because it keeps bad people out of the park," club member Chris Rambarran told the paper.

And so the club began a telephone campaign to get them fixed. It took eight rounds of calls to the transportation department but, the lights went back on and the club received a letter from the transportation department, lauding the role it played.

Getting a street light installed involves a different procedure. The transportation department web site provides no form for this and an operator at 311 had to look into the issue before advising a caller to send a letter to transportation commissioner Iris Weinshall.

But Terry Rodie, of Community Board 13 in Brooklyn, which includes the Cortelyou Road subway station, says improving lighting can be "an easy thing to take care of." Once the request is made to the transportation department, it brings in equipment to measure the light on the street in question and determine whether it is sufficient. Although Rodie said she was not familiar with the Marlborough Road block, she said foliage on trees can make a block seem darker. And she said light from any commercial establishment on the block is also taking account.

In deciding whether to grant the request, says de Bourbon, the department follows guidelines set out by the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America. "It's really more scientific than you think," she says.

The "real hang up" in improving lighting, says Rodie, is not the city but Con Ed. "They have a backlog with this kind of thing."

(Do you have dark streets or broken street lights in your neighborhood? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Gail Robinson

|

Filling In The Potholes

Â

Michael Gilpin is an aspiring actor with a day job in Manhattan, a shared apartment in Astoria, and a car with a blown suspension system. In February, while driving home from a friend's house in Brooklyn, the front tire on Gilpin's silver Geo Prism fell into a fissure on the Van Wyck Expressway in Queens — a classic pothole notable primarily for its size, which he estimates at about 18 inches deep.

Michael Gilpin is an aspiring actor with a day job in Manhattan, a shared apartment in Astoria, and a car with a blown suspension system. In February, while driving home from a friend's house in Brooklyn, the front tire on Gilpin's silver Geo Prism fell into a fissure on the Van Wyck Expressway in Queens — a classic pothole notable primarily for its size, which he estimates at about 18 inches deep.

"I fell off a shelf into an abyss," Gilpin says. "I felt it in my throat. I was in flight." He pulled to the side of the road to investigate. "The tire was flattened. Pieces blown. I had a spare. I had a jack. I had my girlfriend watch for my life."

For city drivers like Gilpin, potholes are a fact of life. He and his friends refer to the pothole-riddled area around the entrance to the Queensboro Bridge as "Saigon."

"It's almost unmanageable," Gilpin said.

A winter such as the one that just ended wreaks havoc with pavement in the city. It spurred the Daily News to declare the current situation the worst pothole crisis in the history of New York, to run an ongoing feature entitled Pothole of the Day, and to feature fissures such as one on 78th Street in Middle Village and on Morrison Avenue and East 174th Street in the Soundview section of the Bronx.

According to Department of Transportation spokesperson Tom Cocola, from February to mid-April, the city repaired approximately 53,000 potholes — 18,640 in February alone. That is a 50 percent increase from 2002. After the Presidents Day snowstorm, the city launched what Mayor Michael Bloomberg called "a pothole blitzkrieg," filling approximately 1,600 potholes a day.

But with so many miles of streets and highways in the city, simply figuring out what to fill where presents a challenge. The transportation department counts on its 40,000 workers to look out for potholes. The department also relies on average New Yorkers and provides several resources for pothole victims to report a problem, vent their frustrations and even get reimbursed by the city for car damage caused by a street defect.

One of the fastest ways to report a problem is through the Department of Transportation web site.

The new 311 hotline for non-emergency complaints is supposed to make it easier to complain about potholes. From March 9 to April 21, 2003, the hotline received 3,526 pothole related phone calls, according to the New York Times.

After the mayor said he was "tired of people complaining" about potholes and directed them to phone 311, calls to the hotline about road defects jumped 400 percent, according to the Daily News.

But the transportation department wants details: the precise location of the problem, its size and depth, a description and so on. To help, its web site provides a detailed breakdown of the different kinds of street defects. Is your street plagued by a hummock — a bump resulting from the road being pushed up? Or is it the site of a cave-in, a jagged break in the pavement with a large void beneath? Photos of these problems, as well as of traditional potholes and protruding manhole covers, help readers understand what, exactly, popped their tire or loosened their chassis.

The department tries to repair each reported defect within 30 days. But it has not always succeeded. An audit released in November found it took an average of 57 days for the transportation department to repair potholes — 98 days for defects in the Bronx.

The city promised in late April that it would have about 35 crews of three to four people each working to repair potholes for 10 days. The Daily News followed one crew recently and found it spent little time working, preferring to shop, buy and eat food, and drive around aimlessly. The transportation department suspended the workers after the story appeared and said it would also take disciplinary actions against four supervisors.

The transportation department web site also offers a link to the city comptroller's office, where residents can report car damage sustained from a brush with a pothole and try to get reimbursed.

While the city blames the particularly harsh winter for the current pothole epidemic, budget cuts may make a bad situation worse as the Department of Transportation cuts back on street renovations that could prevent future potholes. "You never fix a pothole by just filling it," former transportation commissioner Lucius Riccio, who now teaches at Columbia University, has said. "You have to fix the street. A pothole is an indication that the street is failing."

The gloomy prognosis would not surprise Michael Gilpin who sees the pothole as being as much a part of driving in New York City as motorists who run red lights and summer weekend traffic jams on the Long Island Expressway in Queens. "It's an ongoing nightmare," says Gilpin. "I don't drive through Manhattan without expecting potholes."

(Do you have a pothole problem in your neighborhood? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Anne Sachs

|

BAM And Its Cultural District

As a high profile institution that has managed to attract a great deal of public and private funding, the Brooklyn Academy of Music has for years been a lightning rod for community activists leery of the "high" culture -- such as ballet, symphonies and opera - that it is world-renowned for showcasing. Although situated on the borderline between commercial downtown Brooklyn and residential Fort Greene since 1908, BAM (as it is universally called) has recently come to represent the front line of the Manhattan-style development invasion that seems to be slowly rising out of the East River like an occupying army, threatening to subsume Brooklyn skylines and life-styles forever.

Perhaps nothing calls into question the role that large cultural institutions play in the development of neighborhoods more than BAM's $700 million plan to build a new 14 square block cultural district. The BAM Local Development Corporation has been working on the details and financing of this district for years, but things recently came to a head when community activists demanded to have their concerns included in the BAM Local Development Corporation's plans, causing public officials to threaten to pull the project's public funding.

The fear is that the BAM district will import new housing, businesses and cultural facilities and essentially re-engineer the cultural personality, not to mention residential and commercial real estate markets, of Fort Greene. Specifically, community activists are calling for the details of plans to be made public, and for those plans to reflect locally articulated economic development visions and needs.

The process BAM and community activists use to resolve this matter over the next few weeks -- BAM will begin meeting within the month with the Coalition of Concerned Citizens, a Fort Greene grassroots group, to try to work out an agreement -- will do more than determine if BAM can secure public funding. It will serve as a negotiation for Fort Greene's cultural soul. In this instance, the term "culture" is a fig leaf for issues we do not like to name explicitly -- particularly race and class.

In other words, we are faced with a question: Will BAM use its expansion as an opportunity to further engage and support the kind of culture Fort Greene is well known for -- a racially integrated, funky avant-garde flava -- or is BAM striving for a more homogenized, euro-centric kind of sensibility, consumer taste and artistic expression?

An eclectic colony of performing art events, restaurants, up-and-coming artists and students -- a pulsating, multi-income Mecca that attracts people from all over the world and incubates talent and creative energy from the surrounding area -- is an exciting vision. An enclave of overwhelmingly white, privileged residents, artists, merchants and their patrons on the order of the Upper West Side is not. A clue to which the folks at BAM might prefer is evident in a comment by Harvey Lichtenstein, the chairman of the BAM Local Development Corporation: "The life and activity around Lincoln Center make me slobber at the mouth."

David Vine, a PhD student in cultural anthropology who has written extensively on the nexus between cultural and economic development, suggests that BAM's plans are a Trojan horse hiding an economic and racial takeover of Fort Greene. "This is not unique," Vine says. "If you look at the history of neighborhood development and similar projects around the country you'll see that 'cultural development' is a precursor to the displacement of large numbers of low-income people." Vine goes on to say that because it's "hard to argue against and oppose the bringing of culture, this kind of development often masks other interests, particularly commercial ones".

Although BAM is better known for cultural events that require high priced tickets and playbills, to be fair, BAM's offerings also include less high brow poetry slams, world music concerts and Dance Africa, a week long celebration that also features an African-styled outdoor marketplace. Also, what complicates the argument against BAM is that some of its most outspoken community critics are solidly middle class, people who have, perhaps more quietly, already helped make Fort Greene a trendy, pricey neighborhood.

Yet, no matter what your income or race, if you live, work or even pass through Fort Greene it will be impossible not to be affected by what is being proposed. The BAM cultural district has the power to not only completely transform Fort Greene as we know it, but send ripples across Central Brooklyn. The latest fact sheet I've seen issued by BAM promises 1.56 million square feet of development including a visual and performing arts library, a 350 seat theater, 100 units of market rate housing, 250 units of subsidized units and a boutique hotel.

My experience in community development tells me that BAM's negotiations with community activists and elected officials will follow the typical patterns of appeasement, but ultimately the larger commercial interests will prevail. BAM, at least if it is savvy and/or cynical enough, will do just enough to make sure the "community" has a voice in the process, promise local people jobs and retail space, give safe harbor to some local artists and cultural institutions and allow some folks from the hood to shack up in some of the "affordable" housing slated to be built.

It is just a shame that cultural change -- whether it occurs on the West Bank or the Upper West Side -- is so often reduced to an equation of us versus them, light-skinned against dark-skinned people, the haves and the have mores. New York is capable of so much more nuance and possibility. There are very few neighborhoods in this city - yes, Fort Greene included - that couldn't stand to be more diverse in its makeup, more tolerant to change and less parochial in its thinking. It's now up to BAM to prove this is the kind of community it seeks to build.

Mark Winston Griffith, a writer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Essence and Spin, is also founder of the non-profit Central Brooklyn Partnership, which organizes people to build economic power.

To read more about Fort Greene - and to contribute your own news and views, as well as reports of potholes - go to the Fort Greene Gazette, the first of our Community Gazettes.

Zoning To Protect Manufacturing

The city is putting together a vision of the future that involves making changes to zoning in order to transform many neighborhoods. This includes:

- revitalizing the North Brooklyn waterfront with parks, housing and ferries

- converting Manhattan’s far west side into a mix of new offices and apartment houses, sports and tourist destinations,

- rejuvenating Lower Manhattan as a mixed residential, business and cultural community

- creating a new central business district in Long Island City.

Unfortunately, many of these proposed zoning changes collide with some of the most dense concentrations of manufacturing jobs in New York, risking thousands of jobs and potentially reducing the diversity of the city’s economy.

For example, in Long Island City the number of industrial jobs is actually increasing, but Long Island City is nevertheless the target of rezoning, the second rezoning in two years. This subsequent rezoning will increase real estate speculation that has already pushed rents for industrial space through the roof and risk displacement of thousands of jobs. It also risks the factories that build the stage sets and sew the costumes for our cultural and entertainment sectors, the printers who support our financial services and media, and the food processors who help make New York the culinary capital that attracts tourists and feeds our office workers.

In North Brooklyn, one of the other areas targeted for re-zoning, more than 20 percent of the residents who work have manufacturing or other industrial jobs. This community will be profoundly impacted if these jobs disappear, even if replaced by jobs in other sectors that pay significantly less.

The plans to rezone the Far West Side of Manhattan to create a mix of offices, residences, a stadium and expanded convention center will impact dramatically on the Garment Center, portions of which are within or border the rezoning study area. The Garment Center is home to more then 39,000 apparel jobs. These apparel jobs, many of which are in design and marketing, anchor an industry that employs 110,000 people and that is spread city-wide.

The potential for displacement does not necessarily mean that the city should stop its zoning initiatives. The city needs to rezone some areas. However, at the same time that it encourages new development it also needs to put in place new zoning and economic development tools to minimize the risk of real estate speculation and the loss of jobs.

Whatever the conventional wisdom of a few years ago, the truth is, New York City needs its manufacturers. There is a growing disparity in income between the richest New Yorkers and the rest of the city’s population, and this is due in some great measure to an economy increasingly dependent on a narrow range of industries. These industries pay their most highly skilled workers very well but they produce relatively small numbers of decent middle- and moderate-income jobs. The loss of manufacturing jobs and the drop in unionization are part of this trend.

The average annual production wage is $28,250 -- $10,000 more than average wages in retailing, the sector that is often pointed to as an alternative source of employment. Manufacturing jobs are also more likely to offer health coverage and to be accessible to people who would have difficulty finding decent jobs in other sectors. For example, almost two thirds of the manufacturing workforce is immigrant.

The well-being of many local economies depends on a healthy manufacturing sector. Manufacturing is viable in New York City. Seven of the ten largest cities in the United States experienced an increase in manufacturing jobs during the 1990s. Inc. Magazine, in collaboration with the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, recently listed its one hundred fastest growing inner city companies and almost one third were manufacturers.

New York City manufacturers have adapted to New York’s demanding environment. Most are small, entrepreneurial businesses that take advantage of New York’s incredible density, creating competitive advantages for businesses that need to be close to their markets, suppliers, design talent and skilled workers. They can even thrive in multi-storied, multi-tenanted buildings, which may be obsolete for the type of manufacturing more characteristic outside the city, because these dense buildings place the manufacturers at the center of their markets.

At present, New York City does not have the land use tools to promote diversity. One might think that having the least restrictive zoning which permits the greatest variety of uses would foster diversity. It is more likely, however, that it will lead to homogeneity as every property owner seeks the greatest economic return on his own property. For example, in an MX Zone, the type of zoning which is increasingly being used by the city, both housing and manufacturing are permitted without restriction, and over time housing will price out manufacturing. The manufacturing that gives the area its character, acts as a buffer against gentrification and gives employment to local residents, will be lost. Diversity, both of physical form, economic activity and even demographic group, may suffer.

The city needs to create new types of zoning that promote diversity. One new zoning tool should be stable mixed residential-manufacturing zoning. In such areas both uses might be legal and manufacturing could be converted to housing, but a critical mass of manufacturing might be preserved through a dedication mechanism. A possible model is the Garment Center, where someone who converts manufacturing space to other uses must dedicate an equal amount of space for manufacturing. This zoning has helped to preserve more then 8,000 production jobs in Midtown Manhattan.

The city also needs to create a new type of manufacturing district. In some sense, New York City doesn’t really have manufacturing zones. It has zones where many uses can locate, including manufacturing, waste transfer stations, pornography, homeless shelters and offices. The city has even tried to put superstores in manufacturing zones. In many instances, the result of this free-for-all is speculation that undermines business investment.

Planned manufacturing districts (or PMDs) would be limited to industrial uses, their ancillary office uses and the neighborhood retailing that supports a manufacturing area. Such districts promote growth by providing the stability that companies need to make investments. Having planned manufacturing districts would also allow the Department of City Planning to target new development to certain areas without setting off speculation in adjacent areas. These manufacturing districts do not prevent change or preserve companies that are no longer viable businesses. Within such a district competition continues between permitted uses. One area in downtown Chicago has experienced a five-fold increase in the number of jobs since it was designated as a planned manufacturing district.

When the city rezones an area or allows the conversion of manufacturing space to other uses, the value of the property can increase dramatically. The city should recapture a small portion of this windfall through a fee or special assessment that can be used to help stabilize businesses in the adjoining areas and help companies that are displaced. This can be done on a building by building basis, as was the case under the Industrial Retention and Relocation Program run by the Business Relocation Assistance Corporation, or it can be done on a district basis similar to an assessment for a business improvement district.

Finally, the city must build the capacity of not-for-profit organizations to engage in the development of industrial space. Such ownership can insulate tenants from real estate pressures to convert manufacturing space. Rents still increase in response to increases in costs, but not speculation.

The city has already begun to recognize the need to promote a more diverse economy. Manufacturing provides better quality jobs for less skilled workers than other sectors which have already gained greater public attention. Supportive land use policies are absolutely essential to achieve a more healthy economic mix that includes manufacturing.

Adam Friedman is the executive director of the New York Industrial Retention Network

Rent Regulation Awaits Its Fate

State and local officials are preparing to chart the future of rent regulation in New York City. Several forthcoming decisions and votes will determine large-scale changes, such as whether former Mitchell-Lama apartments will move into rent stabilization, and smaller ones, such as how much stabilized rents can increase this year.

First, the Rent Guidelines Board is ramping up to determine this year's allowable increases for leases on rent regulated apartments. The nine-member board, composed of a chairman, two landlord representatives, two tenant representatives, and four public members, will consider owners' operating costs, terms and availability of financing, cost of living indices, and testimony from landlords, tenants, experts, and elected officials.

They will use annual reportsgenerated by their own researchers such as the Price Index of Operating Costs, The Mortgage Survey, and the Housing Supply Report. They will also do their own calculations, get extra analysis of the numbers, and consider what landlords and tenants have to say at their public meetings. Then, they will distill all of the information down, and make a decision.

Last year, the board allowed two percent increases for one-year leases and four percent increases for two-year leases, even though landlords' costs had gone down from the previous year. This year, landlords are claiming that high fuel prices and increased property taxes warrant double digit increases. Tenants will fight to bring that number down, but some think the final compromise will be higher than tenants have seen in a long time. Increases over the past decade have averaged about three percent for one-year leases and five percent for two-year leases.

The board was expected to start its work in March, but some last minute changes postponed their first meeting. Mayor Michael Bloomberg decided to replace five board members, and the background checks of his new appointees took longer than expected. The current meeting schedulebegins in April and runs through mid-June, when board members will cast their final vote.

Meanwhile, the City Council has weighed in on rent regulation, in largely symbolic resolutions, since, under the current structure, state laws run the show. [See Gotham Gazette articles on rent regulation and the battle over rent regulation.] On March 12th, the council voted to renew the city's rent stabilization law though April 1, 2006. It also passed two resolutions that would try to influence the state legislature, as it reconsiders rent laws which will expire on June 15th.

One resolutionurges the state legislature to repeal the Urstadt Law, which was passed in 1971 and handed state legislators control over rent regulation by forbidding the city from making any rent laws that are stricter than the state's.

The Council resolution says, "the regulation of these rent stabilized and rent controlled dwelling units is more appropriately a matter of local concern and should be subject exclusively to decisions made by the Mayor and the City Council." It also says that the Urstadt law prevents the city from "exercising home rule over an issue of vital local importance."

The other resolutionsupports the State Assembly's passage of a bill that would renew rent regulation until 2008 and alter certain elements of the 1997 laws that regulation proponents dislike.

The bill would eliminate high rent vacancy decontrol, which has deregulated apartments that rent for $2000 or more upon vacancy. Critics have said that nearly 100,000 apartments have been deregulated under this provision, and it could eventually dismantle rent regulation as a whole. The bill would also drop the allowable increase in rent for vacant apartments from 20 percent to 10 percent, and extend rent stabilization to former Mitchell Lama developments and former Section 8 housing developments. Finally, it would stop landlords from abusing the provision of the law that allows apartments to be removed from rent regulation for personal use.

The Assembly passed the bill in early February, and the City Council called upon the State Senate and the governor to sign it into law. The bill has been introduced into the State Senate by a few Republican senators who represent districts in New York City. It now sits with the Senate committee on Housing, Construction, and Community Development. It is not likely to be supported by many other Senate Republicans, who have said they want to keep the rent regulation laws as is, and who comprise the majority in the Senate. And Majority Leader Joe Bruno has said he will not touch rent regulation until the legislature passes a budget.

More than one million households under rent regulation are awaiting the final decisions with no small amount of anxiety. And while tenant advocates see the current bills as a strong starting point for the inevitable negotiation among Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, Bruno, and Governor Pataki, they also know, from long experience, that anything could happen.

Rebecca Webber is a journalist who has covered housing issues for Gotham Gazette since July 2000.

Bringing Sand to the Brooklyn Beach

On a March day when the temperature touched 70 degrees in Brooklyn for the first time since last fall, the United States Army Corps of Engineers presented a new plan at a public meeting in Coney Island to bring sand to a beach. They showed aerial photographs of Coney Island beaches that appeared wide and full, while, just to the west, there was a severely depleted beach near the gated community of Seagate.

The corps, the federal agency responsible for maintaining the nation's shores and navigation channels, wants to restore the level of sand at the Seagate beach to the way it was 15 years ago, and shore up a large pile of rocks at West 37th Street, known as a "groin," that holds sand in place for Coney's Island public beaches. Groins can be many hundreds of feet long and several feet high. The corps proposal calls for the construction of four groins at the southwest tip of Coney Island near Seagate, which will then trap and hold sand along the Seagate beach. A wide sand buffer at Seagate is necessary, in the corps' view, to bolster and protect the 37th Street groin from a storm that could attack the site from the side ("flank") and undermine the effectiveness of that groin.

The corps is joined in this effort by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Funding (65 percent federal, 24.5 percent state and 10.5 percent city) was secured through the efforts of Congressman Jerrold B. Nadler.

The army's engineers are not new to the Brooklyn beaches. Ironically, some critics say, the work the corps is proposing is intended to fix problems that the corps caused in the first place. Coney Island was a corps project in the 1920's, and they addressed the Seagate peninsula again in the late 1980's and early 1990's.

Residents living on Gravesend Bay, the north side of the Seagate area, contend that sand drifting around the peninsula, perhaps the result of the lengthy 37th Street groin and other corps construction projects, is damaging their community. One resident spoke of sand drifting into Kaiser Park, covering pathways and benches. Another bayside resident spoke of sand drifting into people's homes. A third resident, stated, "we now have 300 feet of beach we did not have twenty years ago." These residents asked the corps to use this "excess" sand to replenish south side beaches. The corps estimates that bayside sand could account for 30,000 of the 190,000 cubic yards it needs.

The corps' Edward Wrocenski, stated that "T-Groins are the best chance for the sand to stay in place" on the oceanside. He indicated that T-Groins have worked in New Jersey and elsewhere. Some people attending the public meeting did not agree..

Sand moves naturally by long shore ocean currents and storms. The corps is engaged in many locales around the country, building groins and jetties, and mining and moving sand. These methods are expensive. Where it is necessary to both build and replenish, it is even more expensive. And some corps opponents question the wisdom of long term beach projects that primarily benefit private property owners.

Environmentalists also raise concerns about the impact of corps projects that dump large volumes of crushed stone onto sensitive underwater inter-tidal habitat. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service fears disruption of the foraging behavior of the species they protect.

Still, the corps and the state contend that the $450,000 study and the $9 million project "are not about a beach for Seagate". The agencies say the project is about preserving the groin that holds the sand that makes the Coney Island public ocean beaches possible while keeping sand out of the homes of residents on the bay side. Some observers wonder if T-Groins will work.

Peter B. Fleischer, currently writing a book on the New York City waterfront, was formerly a transportation and environment policy advisor to New York City Mayors David Dinkins and Rudy Giuliani.

New York City's Big Planning Projects: Avoiding the Public?

Over the last year, city government and public agencies launched an unprecedented number of bold plans that could transform the face of New York City for decades to come. In the midst of the excitement and fascination with these plans in the local press, there is little recognition that most of these developments could bypass the process that was set up for public debate, discussion and decision making. Despite a more open environment at City Hall ushered in by the Bloomberg administration, some of the most important decisions about the future of the city are being made behind closed doors.

THE NEW PLANS

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has a new plan for lower Manhattan. Also planned downtown is the winning design by architect Daniel Libeskind for the World Trade Center site. There is the ambitious plan for the 2012 Olympics, which includes a new stadium on Manhattan's west side, an expanded Jacob Javits Convention Center, a 4,400-unit apartment complex in Hunters Point, Queens, and dozens of other projects in the five boroughs. The Olympics plan overlaps with the recently-announced plan for Midtown West, which would allow up to 40 million square feet of new office and residential space over the next 30 years and extend the #7 subway line from 42nd Street. All together these projects could cost upwards of $10 billion in public money.

THE PUBLIC APPROVAL PROCESS

The city has two procedures for approving major plans that are set out in the city charter. One is the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP). This process involves public hearings and votes by community boards (there are 59 in the city), borough presidents, the City Planning Commission and the City Council. The mayor plays a powerful role because he appoints the majority of the members of the City Planning Commission and has veto power over City Council actions.

The second procedure, also established in the city charter, is for approving plans. It calls for a review process similar to ULURP, and follows planning guidelines set by the Department of City Planning. Since authority for these plans is to be found in Section 197-a of the city charter, they are often called "197-a plans." All official city plans, whether initiated by city planning or community boards, are 197-a plans.

ULURP was set up in the mid-1970s to give neighborhoods a voice in decision making. Before that, the city's neighborhoods had no way of systematically taking part in decisions that would affect their futures. In the 1960s, many neighborhoods rebelled against official top-down urban renewal plans that wiped out whole blocks and displaced thousands of people. They successfully fought giant projects like the Lower Manhattan Expressway through grassroots organizing and protest. And disenfranchised African American neighborhoods rose up to demand community control of neighborhood schools. Under ULURP, neighborhoods now get to review and vote on most major land use changes, including urban renewal plans, zoning changes, and the acquisition and sale of city-owned land.

Responding to neighborhood demands for a greater role in planning, the charter was revised in 1989 to give explicit authority to community boards to introduce their own plans. Community boards were also promised professional planning assistance, a charter principle that has yet to be put into practice.

EVADING THE PUBLIC PROCESS

Officials have a treasure chest full of legal devices for evading ULURP and the 197-a planning process should they choose to do so. One of these devices is the independent authority set up under state law. Authorities like the Empire State Development Corporation, and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, for example, can override ULURP and local plans, and thereby ignore local zoning and development rules. The bi-state Port Authority of New York & New Jersey, which owns the World Trade Center site, has similar powers.

The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) is a subsidiary of the state's Empire State Development Corporation, and effectively operates outside local planning procedures. In the Midtown West and Olympics 2012 proposals, many of the major projects, including the stadium and transit expansion, could be accomplished through independent authorities. State government and the authorities, quite understandably, have never made a commitment to use ULURP or 197-a as instruments to gain local approval of their plans.

But neither has City Hall protested very much or demanded that planning follow the procedures set out in the city charter. Instead, the mayor's office seems to be satisfied by issuing its own plans and negotiating with the authorities behind closed doors. While the mayor has stated his desire to gain more local input in the planning of lower Manhattan, now controlled by the state-dominated Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, the new input would apparently be tightly controlled by the mayor. Thus, instead of launching a 197-a plan for lower Manhattan that would have to involve broad participation, the mayor chose to cook up his own plan.

As Jennifer Steinhauer noted recently in The New York Times, Mayor Bloomberg's background as a successful corporate chief executive officer has led to a style in City Hall favoring "private talks and public silence." Even when the proposals may have laudable qualities, and some of them certainly do, many people wonder whether they respond just to the interests of the insiders and leave out those for whom access to government has always been an issue.

The public participation process can be loud and messy, and produce unexpected results. But so can negotiating in the mayor's smoke-free rooms. And isn't an open and transparent political process what distinguishes democracy from autocracy? When the Civic Alliance, a coalition of 85 civic and community groups, organized Listening to the City, a gathering that brought over 4,000 people to the Javits Convention Center in July of last year, the participants gave a giant thumbs-down to the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation's proposals for Ground Zero. It is no wonder that the corporation, fearing another slap in the face by the public, turned down the Civic Alliance's proposal for a repeat performance to discuss the recent design competition. But why isn't the mayor proposing a 197-a planning process for lower Manhattan that would give all New Yorkers and interested parties a chance to contribute their ideas and energies to this strategic rebuilding effort?

There is another route used to evade ULURP and city planning. It is the Board of Standards and Appeals, a semi-administrative body that helps developers skirt zoning rules in a way that can transform entire neighborhoods without any recourse by the public. But that exercise in undermining democracy we will leave for a a future column.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Planners Network Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

The State Of NYC Housing, According To The Census Bureau

The mayor and the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development have released preliminary results (in pdf) from the 2002 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey. The U.S. Census Bureau conducts this survey every three years, primarily to determine the rental housing vacancy rate, which must remain below five percent in order for rent regulation to continue.

The vacancy rate, measured between February and June 2002, was 2.94 percent. In the 1999 survey, the rate was 3.19 percent, although the 2002 data has not yet been weighted to allow accurate comparisons to data from previous years.

"We still face the problems of a serious housing shortage, affordability, and crowding because the city is a desirable place to live," said Mayor Bloomberg in a press release that accompanied the release of the data. He said he supported the rent regulation laws as they exist today. Those laws are set to expire this June, and a heated battle will surround their renewal.

Beyond the rental vacancy rate, the survey offers a vast array of information about housing. The preliminary information currently available (the full tables will be released in about a year,) includes some surprising and revealing things about the city's housing stock.

Just what those numbers reveal, however, might depend on who you ask.

RENT

The survey found that in 2002, the median monthly gross rent was $788 for all units. For non-regulated units, it was $850, an amount that appears incredibly low, even for a housing market that has softened in recent years.

Location is one explanation.

"Most New Yorkers don't live in Manhattan, said Joe Weisbord, staff director of Housing First!, a coalition that promotes solutions to the city's affordable housing crisis. "[The $850 median] probably reflects a lot of apartments in the outer boroughs."

As was reported in Gotham Gazette's Issue of the Week entitled "The Fight Over Rent Control", another understanding emerges from a recent study by the tenant group New York State Tenants & Neighbors. The study analyzes data from the 1999 Housing and Vacancy Survey and among other things, calculates the median rent, excluding buildings with fewer than six apartments and single-family homes.

"If you include small buildings that have never been regulated, and homeowner neighborhoods in Queens, that's a very different kettle of fish, in terms of their location, their desirability, and in terms of landlord-tenant relationships," said Michael McKee, associate director of New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition. "We compare regulated rents and unregulated rents in buildings with 6 or more units, because to be rent-stabilized you need to be in a building with six or more units."

For 1999, their study found that the median monthly rent for rent-regulated apartments was $640. For unregulated apartments, it was $1090. In Manhattan, the numbers were $766 per month for rent regulated apartments and $2000 per month for unregulated apartments.

VACANCY RATES

The 2002 Housing and Vacancy survey found that rental vacancy rates varied by borough. For 2002, Manhattan's rate was 3.86 percent, the highest of the five boroughs.

"Manhattan is really a unique animal, very different from the housing market in the rest of the city," said Jack Freund, executive vice president and chief economist of the Rent Stabilization Association, the city's largest landlord group. "What you are seeing here is that the highest rent levels are in Manhattan."

Costly apartments tend to be in Manhattan, and the survey found that vacancy rates increased with rent levels. The rate for units asking $1750 per month or more climbed to 9.25 percent. For units asking $2,000 per month or more, the vacancy rate increased to 10.05 percent.

The stumbling economy might have something to do with those increases, but there are other possible explanations.

"There are more of those units coming onto the market, probably because of new construction in high rent units and vacancy decontrol of high rent units," said Freund.

Tenant advocates suggested that vacancy rates also remain high for higher rent apartments because those owners are often willing to keep their units vacant longer in order to find a tenant who is willing and able to pay.

VACANT APARTMENTS

The survey found that 2002 had the highest number of vacant units not available for sale or for rent since 1965, when the first Housing and Vacancy Survey was conducted. About 32 percent were unavailable awaiting or undergoing renovation, the highest number since 1987.

"That's a consequence of owners putting money back into their building, which they are able to do if they get rent increases," said Freund of the landlord group.

But tenant advocates thought renovations were a way for landlords to remove apartments from rent regulation.

"Landlords are spending lots of money on renovating apartments because with vacancy decontrol in effect, if you can get the rent above $2000 a month, you can take it from rent regulations forever," said McKee, of Tenants and Neighbors.

Also, 43,000 apartments, the highest number since the survey started counting them in 1978, were unavailable because of occasional, seasonal, or recreational use. More than six in ten of those apartments were in Manhattan.

Some attributed this to corporations that keep such apartments for the use of occasional corporate guests. But others saw it differently.

"It points out another structural problem with rent regulation that causes people to hold onto apartments even if they don't need them as their prime residence," said Freund. "We know that is a phenomenon that happens with apartments because the rents are so far below markets so you hold onto them even if you don't use them with the result that apartments are less available for the general population."

RENT REGULATION

Almost 22 percent of rent-controlled apartments were occupied by tenants who moved in after 1971, most likely utilizing succession rights. That means that nearly 80 percent of rent-controlled tenants have lived in their apartments since 1971 or before. In most cases, those tenants are now aging or elderly.

The data disproves the popular misconception that many of today's tenants under rent-control are lucky beneficiaries of family members' apartments.

"The reality is you can't just pass on your rent-controlled apartment to your nephew in Arizona," said McKee. "To have the right of succession, the family member has to actually live there. People who try to manufacture a situation that doesn't exist don't get away with it."

However, some see a problem in the long-term habitation encouraged by rent control.

"I think it speaks to the essence of the negative effect of rent control on the market. It takes units out of the housing market and reduces the general availability of housing for the majority of New Yorkers," said Freund.

Tenants in rent-controlled apartments actually seem worse off than their non-regulated counterparts. Their median income was $20,120 in 2001, less than two-thirds the median of all renter households. This can probably be explained by the advanced age and fixed incomes of such tenants.

"In fact, rent control incomes have gone up simply because the really old tenants have died off," said McKee. "In 1970 there were 1.1 million. Today you have 60,000, so it's a program that is being phased out."

HOUSING AND LIVING CONDITIONS: GOOD NEWS AND BAD NEWS

In 2002, housing conditions in the city were the best since the Housing and Vacancy Survey started asking about them. Housing advocates are pleased, but not surprised, by this revelation.

"I think you are looking at a century long trend in terms of improved conditions," said Weisbord of Housing First! "Housing conditions are, in general, extremely good, though there are still pockets of very poor quality housing in NYC."

As an example, the survey found that crowding remained a serious problem in 2002 — 11.1 percent of all renter households were considered crowded - with more than one person per room.

All in all, there are differing conclusions to be drawn from the revelations in the preliminary data.

"I think what is interesting is that housing remains very affordable," said Freund of the Rent Stabilization Association. He noted that the median household paid about 28 percent of their income in rent.

Tenant advocates, instead, focused on the continuing descent of the overall rental vacancy rate. "It is reflective of this very serious shortage that we have and we need to produce a lot of new housing and housing that is affordable for a wide range of income levels," said Weisbord.

Rebecca Webber is a journalist who has covered housing issues for Gotham Gazette since July 2000.

Waterfront Housing For Everyone

In my district in Brooklyn, there are acres of manufacturing land on the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront slated for residential rezoning. Development of this land is expected to yield up to 10,000 houses and apartments in the next few years and dramatically alter the community. While new apartments are desperately needed in the area and the city as a whole, there is also a great need for affordable housing in this lower-income neighborhood.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has announced an ambitious new housing plan, but because of the state and city budget woes — and federal government indifference — housing subsidies have been greatly reduced. To create enough affordable apartments in places like Greenpoint-Williamsburg, we must find new and innovative policy tools.

One possible solution is to link affordability to the zoning regulations by allowing developers to build slightly bigger if they dedicate some of their profit for the creation of affordable housing. In certain dense areas of Manhattan, a similar special zoning category already exists called, "inclusionary zoning." Developers who build residential apartments in these districts can build a little higher if they include a sizable percentage of the apartments for low-income households. The program has spurred the development of hundreds of low-income homes in the densest areas of Manhattan, but it has not yet been developed for use in less dense districts in the other four boroughs.

Some have argued that the program is not viable outside of Manhattan. However, I believe a modified version of the program could work on rezoned land – particularly those on the city’s attractive and highly developable waterfront. Land zoned for residential development is significantly more valuable than land zoned for manufacturing use, and so landowners on the Brooklyn waterfront will benefit financially with these changes. I believe that asking these developers to contribute some money to low-income housing is reasonable.

Some of the manufacturing land in Greenpoint-Williamsburg has already been developed for housing, though the property has not been rezoned. Developers of this land obtained a "use variance," the rights to build housing where they normally could not, by proving that they couldn’t make money if they complied with existing zoning regulations. Once again, the city is helping developers who will see the value of their property skyrocket. I propose, in the future, requiring these developers to commit to making 20 percent of new residential construction affordable for a typical family in the development neighborhood. Unused manufacturing land represents some of the last stretches of vacant land in the city. Unless the city intervenes, there is no guarantee that any low and moderate income New Yorkers will be able to live in any of the thousands of new apartments developed on these vast tracts. We cannot afford to ignore this opportunity to build affordable housing. The residents of New York City, not just the wealthy ones, deserve a chance to reap the benefits from the development of the Brooklyn waterfront.

New York City Councilmember David Yassky represents district 33 in Brooklyn.

Related Article:

Critiquing The Mayor's Housing Plan by Mark Berkey-Gerard

The Battle Over Rent Regulation

The rally outside Manhattan Housing Court last week started with a chant:

The rally outside Manhattan Housing Court last week started with a chant:

"What do we want?"

"Stronger rent laws!"

"When do we want them?"

"Now!"

It continued with speaker after speaker delivering passionate arguments, dire predictions and fiery exhortations:

"Let's get ready to rumble," one speaker said, while the crowd stamped and cheered in the cold. "We went through this in 1997. We're ready for them again. This is the next civil rights movement."

"I live in a rent-stabilized apartment," the speaker continued.

"I do too!" a few shouted out.

"I've been there for 48 years," the speaker said. "I grew up there. I'm not going anywhere!"

Anybody not well-acquainted with the war over rent regulation might have been surprised to see that most of the speakers being cheered at this rally — most of the speakers, period — were members of the oft-invisible New York State Legislature. (The rent-stabilized resident, for example, was Assemblymember Keith Wright from Harlem.) All those who were present represent New York City, and all of them railed against their upstate colleagues.

For millions of New York City apartment dwellers, the decision that will determine whether they can remain in their homes or be forced out will be made not by landlords across New York City but by legislators 150 miles away in Albany.

With the current law set to expire in June, it is time for the state government to decide whether to renew rent regulation. While the exact size of rent increases in most regulated apartments is determined by the city Rent Guidelines Board, the state government decides whether rent will be controlled at all and, if so, under what circumstances.

WHAT THE LAW DOES

Rent control began in New York in 1943, dictated by the federal government as a means to prevent rampant inflation during World War II. After the war ended and price controls were lifted, the state moved in, allowing municipalities throughout the state to control rents. Today, the state's rent regulations protect 2.5 million tenants living in more than a million apartments in New York City alone. Fifty other municipalities in the state also regulate rents.

Tenants leaders and other advocates see rent control as vital to insuring that New Yorkers, many of whom are life-long renters, do not lose their apartments because of the vagaries of the real estate market. Opponents argue that rent regulation interferes with the housing market, removing incentives for developers and landlords to create more housing. (See related story )

New York provides a variety of protections for tenants of rent-regulated apartments. The laws allow the city to put a cap on how much landlords can raise rents of occupied apartments. Currently, landlords in New York City can hike the rent by 2 percent for one-year leases and 4 percent for two-year leases.

In addition, landlords must renew their tenants' leases when they expire. And tenants have succession rights, meaning that they can pass their apartments on to a relative or a romantic partner. The rent laws also allow tenants to join tenant groups and fight for repairs without being retaliated against by their landlords.

THE LEGISLATIVE BATTLE

The battle over enacting new laws is already underway. Tenant advocates have begun organizing rallies and lobbying state legislators to ensure that when the June 15 deadline comes around, the new rent laws will provide better protections than the existing laws do. Landlord groups have generally urged the elimination of rent control.

In 1997, the last time the law came up for renewal, Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno vowed to end rent regulations. The Democratic controlled Assembly passed its own bill renewing the rent laws well before the expiration date. But the Republican Senate did not move to consider the issue until the deadline neared, giving the Senate the leverage it needed to weaken the Assembly's bill.

By the time the measure passed, it was so weak that tenant advocates claim that one way Albany could guarantee the end of rent controls is simply to simply renew the rent laws as they currently exist.

The state's top two Republicans, Governor George Pataki and Senator Majority Leader Joseph Bruno, have both come out publicly in support of renewing the rent laws "as is."

Such a renewal "would cause a slow death for the rent laws," said Democratic State Senator Liz Krueger of Manhattan who sits on the Senate housing committee.

The Democratic-controlled New York State Assembly got an early jump on the issue when it passed its rent-regulation bill on February 3. The Assembly's bill adds some tenant-friendly provisions to the current regulations and would be in effect until 2008.

Currently, controls on apartments are lifted when an apartment becomes vacant if that apartment can be rented for more than $2,000 a month. The Assembly bill, A.2716a, would end the that.

Tenant advocates see this as crucial. "If this is not repealed," said Dave Powell, an organizer at the city-wide tenant union Metropolitan Council on Housing (Met Council), "It will be the death of rent regulation in New York City." Tenant advocates estimate that almost 100,000 apartments have been removed from rent regulations since 1993 because of this provision.

Powell believes that, with the way rents are increasing in New York City, landlords will one day be able to claim that any apartment could rent for $2,000 a month, which would mean that all apartments would be exempt from regulation.

"If you are a talented businessperson you can absolutely figure out how to get your apartments out of rent regulation," Krueger said.

Landlords are now allowed to increase the rent of a regulated apartment by 20 percent when it becomes vacant and to add on one-fortieth of the cost of any renovations made while the apartment is vacant.

The Assembly bill would reduce the amount that landlords can raise the rent on vacant apartments — the so-called vacancy allowance — to 10 percent of the current monthly rent. It would place under rent stabilization apartments built since 1974 under the Mitchell-Lama program, which provided incentives to developers to build middle-income housing. The current regulations do not include any apartment buildings built after January 1, 1974.

Though the Assembly's bill is more tenant-friendly than the current laws, it does not go far enough for some tenant advocates. Powell faults the measure for not repealing the Urstadt Law, which bars New York City and the other 50 municipalities around the state that have some form of rent regulation from enacting rent laws stricter than those of the state.

"In effect, the law allows the city to weaken the rent laws but not strengthen them," Powell said.

The Assembly's bill now moves on to the Republican-controlled Senate where it is expected to take on a decidedly more pro-landlord look.

"The Republicans controlling the Senate are opposed to rent regulation," said Krueger, who hopes the Senate passes a bill identical to the Assembly bill. "My Republican colleagues from up state do not understand what a housing crisis is like and why we in the city need rent regulations."

A spokesman for Bruno, refusing to talk specifically about what the majority leader plans to do, would only say that the "New York State Senate is dedicated" to providing affordable housing to New Yorkers.

The Senate seems in no hurry to move on the issue . "We have several months before the rent laws expire," said Mark Hansen, a spokesperson for Bruno. "However, the Senate has a much more pressing deadline of April 1, when we need to have a budget passed."

"We are starting ahead of the game this year," Krueger said, noting that in 1997, Bruno was "publicly on record wanting to end rent regulations, but this year he wants to keep them the same." Hansen noted that Pataki also wants to keep the laws as they are now.

The Met Council and other tenant advocacy groups plan to keep the pressure are already organizing to put pressure on and push for stricter regulations. On May 13, "Tenant Lobby Day" in Albany, advocates will hold a rally and lobby legislators. And on June 1 — only two weeks before the regulations are set to expire — tenant advocates will hold a rally at Union Square.

Related Article:

Rent Regulation by Robin Reisig

Rent Regulation

To hear the most adamant landlords and their supporters tell it, rent control has just about destroyed New York

City, denying real estate developers the opportunity to build affordable housing for a reasonable profit.

To hear the most adamant landlords and their supporters tell it, rent control has just about destroyed New York

City, denying real estate developers the opportunity to build affordable housing for a reasonable profit.

Tenants and their advocates believe just the opposite, that rent regulation has saved the city. It has enabled New York to remain a magnet for the young and the gifted and the hopeful, and protected the average New Yorker from the greed of the real estate industry.

The two sides have been making the same arguments for several generations, in a conflict that has seen many battles. Some New Yorkers wonder if one side has already won. How can anyone say that rents are regulated now, when an apartment can triple in rent when it becomes vacant, and a crummy one-bedroom apartment in Manhattan can go for $2,400 a month?

On the other hand, many New Yorkers who live in rent-regulated apartments — and rent regulation still covers slightly more than a million apartments in New York City, or about half of the city's total number of rental apartments — cannot seem to believe that all regulations might actually come to an end.

But that threat is real, tenant advocates say — Republicans in the New York State Legislature tried to abolish it six years ago — and, with the current rent regulations set to expire in June, they have mobilized their forces to preserve and strengthen the laws. (See related story.)

A CITY OF RENTERS

New Yorkers have a uniquely proprietary attitude toward their apartments. Elsewhere in the country, middle class people buy big houses with lawns. New Yorkers hope for a sunny window to rent. Other Americans live in apartments until they settle down and acquire a spouse, a kid, a dog — and a house. Many New Yorkers do their settling in their apartments; some two-thirds of New Yorkers are renters.

At the same time, housing costs are notoriously high here. The average New Yorker currently spends almost 30 percent of income on rent, including gas and electricity. More than a quarter (27 percent) of renters spend half or more of their income on rent, according to a 1999 census housing and vacancy survey.

It is not surprising, then, that rent regulation remains one of the hottest issues in New York, with people on both sides holding fiercely to their positions. Landlords and advocates of a freer market for housing say rent controls reduce tax rolls and discourage new construction.

"With 1.1 million rent-regulated apartments, the city is a showcase for the distorting effects of controls," wrote Peter Salins of the Manhattan Institute. He cited "a minuscule vacancy rate, middle-class families trapped in apartments too small for their needs, wealthy retirees paying a pittance for three bedrooms and virtually no new construction to relieve the strain and to upgrade the housing stock."

Tenants counter that rent control was instituted to protect renters from being exploited. "The rent laws were enacted to eliminate unfair bargaining advantages that landlords have over all consumers who are forced to shop for apartments in an overheated market," wrote Timothy Collins, a former executive director and counsel for the city Rent Guidelines Board. "The law was designed to ensure that a landlord could not charge $1,200 for an apartment that — in a normal market — would rent for only $800."

Collins and other tenant advocates say the drive to loosen rent regulation or to do away with it springs more from the political power of the real estate industry than from the merits of a free market argument.

A LONG HISTORY

While rent regulation may have particular immediacy in crowded, expensive 21st century Manhattan, people have sought to regulate the housing market for centuries. The movement gained momentum in the early 1900s. "Because housing markets, like labor markets, are often anarchic and unstable, the trend throughout the century, learned through bitter experience, has been to subject them to government regulation and intervention in order to try to assure some degree of public peace and justice," Ron Lawson wrote in his book, "The Tenant Movement in New York City, 1904-1984."

Faced with a housing shortage and high rents after World War I, the state legislature enacted laws allowing tenants to legally challenge "unjust, unreasonable and oppressive" rent hikes. These laws stayed on the books until 1928.

In 1943, the federal government's World War II Office of Price Administration largely froze rents in New York City. Tenants organized to preserve the protections after the war, and in 1947 New York established a state rent regulation system controlling rents on all residential buildings constructed before 1947. Today, only about 60,000 apartments remain under that old rent-control law.

In the face of rising rents in 1969, New York City enacted rent stabilization, which extended regulations to buildings with six or more units constructed after 1947. This system today covers at least a million apartments. (One result is a confusion over terminology. Some people refer to "rent control" to mean both the earlier rent control system and the later rent stabilization. Others insist that it is important, and more accurate, to make a distinction between the two, and when talking of both of them together, to say "rent regulation.")

Both rent control and rent stabilization officially exist in response to a housing shortage, and would terminate if the number of vacant apartments in New York City ever rose above five percent of the total housing in the city, which has never happened, according to the official survey.

Concern about housing abandonment, a growing problem at the time, prompted the city to weaken rent regulation in 1971, permitting larger rent hikes. The state legislature also instituted so-called vacancy decontrol, which removed vacant apartments from rent regulation.

Rent regulations for all apartments thus seemed doomed. Tenants and their supporters contended that the changes sent rents skyrocketing and were driving people out of the city. In response, the legislature ended vacancy decontrol in 1974.

Observers differ over how much effect the regulations actually have on rents. Barbara Elstein Katz, a retired analyst with the Department of Housing, Preservation and Development, has calculated on behalf of the New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition that the median monthly amount that tenants pay to landlords for rent-regulated apartments in the city is $640, while for unregulated it is $1,090 — 70 percent more.

Landlord advocates say this is not true, that there is less than a $150 difference. According to Dan Margulies, executive director of Community Housing Improvement Program (CHIP), a trade association for apartment building owners, the median unregulated rent in 2002 was around $850.

The discrepancy is because Marguilies includes the small mom-and-pop buildings (buildings with fewer than six apartments) in his calculation, and Katz does not.

CHANGES IN THE SYSTEM

|

CHALLENGING RENT HIKES Under rent regulations, tenants can appeal to the state Division of Housing and Community Development, claiming that their rent is too high. But such a challenge requires detective work. Vivian Dee, head of the Park West Village Tenants' Association in Manhattan Valley, has become an expert. Last year, for example, she helped two tenants who thought they were being overcharged on rents for their separate apartments. Looking over two canceled checks the landlord had provided as evidence of improvements made to the apartments, Dee noticed something odd. "The date of the check was the same. . . . The amount of the check was the same. The number of the check was the same," she recalled. "I was overjoyed." Dee was delighted because the identical $14,550 checks bolstered the tenants' call for a rent reduction. The owners had claimed that the full amount of the check was for only one apartment. A quick look at other checks revealed that this was not the only time the same check had been used as alleged proof of work for more than one apartment. "It was a mistake," said Santo Golino, a lawyer for the landlords, P.W.V. Acquisition. "I think we've fully explained it satisfactorily" for the state. Golino declined to give that explanation. Park West Village, huge high-rise buildings, between West 97th and 100th Streets, near public housing projects, was built with government help as affordable housing. The tenants' association advises new tenants to check to see if their rents are legal. The new Park West Village tenants have won a number of their cases at the state housing division, but the landlords are appealing most of the decisions. Linda Anderson, a college professor and single parent of a 6-year-old son, had been paying more than half of her net salary for her $2,400-a-month apartment at Park West Village. When she looked into her new apartment's rent history, she discovered, "Lo and behold, to my amazement, the rent had been increased" from $935.95 to $2,400. While the landlord claimed $50,000 in work had been done on the apartment, the cabinets do not align, and the paint and plaster are uneven. In the bathroom, tiles are cracked, and paint has dribbled down onto the tiles. She now pays less than $1,200. Anderson said, "I felt like I had really once tested out the system and challenged it and heard that my voice was heard" |

While rent control survives, the state has whittled away at it over the last decade.

Rent controls are "almost like a drug. We all grew up in that kind of environment," said Joseph Strasburg, president of the Rent Stabilization Association, which represents property owners. "We cannot end it overnight."

But tenants see an effort to phase it out. A law passed in 1993 allowed landlords to add one-fortieth of the costs of any improvement they made to a vacant apartment to the rent charged the next tenant. In 1993 the City Council and in 1994 the State Legislature decontrolled rents on vacant apartments renting at $2,000 a month or more if the new occupants' household income was $250,000 for two consecutive years.

In 1997, the New York State Legislature extended the rent stabilization law for another six years — or at least that is what many New Yorkers believed. From the apartment owners' point of view, the 1997 law fixed a flawed system. From the tenant point of view, it created injustices (pdf file) and threatened the very existence of rent regulation. Republicans such as Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno now are willing to let the current law stand — testimony, some observers say, to just how weak that legislation is.

The 1997 law included vacancy decontrol for so-called luxury apartments, costing $2,000 or more a month, regardless of the new tenants' income. Landlords discovered all they need to decontrol the rent on an apartment is for it to become vacant.

Landlords can immediately increase the rent on a vacant apartment by at least 20 percent—more if the departing tenant had lived in the apartment for more than eight years. The landlord can also add to the monthly rent one-fortieth of the cost of any repairs made to the home.

If the rent was $1,000 when the tenant moved out, "the rent immediately goes to $1,200. The landlord gets that without a lick of work," explained Michael McKee, associate director of New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition.

Then, McKee continued, "The landlord asks himself, 'How much do I have to spend to get the rent up to $2,000?' The answer in this case would be $32,000, because the landlord can add one-fortieth of the costs of improvements to each month's rent — forever."

So, McKee said, the landlord puts in new floors, wiring and other things, and "the apartment is forever de-regulated."

Landlords don't even need to document that they have actually done the work unless a tenant challenges the rental price.

Landlords say these rent hikes are fair. "I don't think landlords generally are responsible for what somebody will pay if they want to live in a particular area," said Margulies of the Community Housing Improvement Program. "I used to live on Upper West Side, and I couldn't afford it so I moved. This is apparently a foreign notion to most New Yorkers: There is no God-given right to live where you want to live."

Owners and tenants dispute how many apartments have been deregulated to vacancy decontrol. Owners say no more than 50,000 or 55,000 units. Tenants say 99,000.

When a building becomes a co-op, rental units in the building are decontrolled as soon as the current tenant leaves.

"We calculated that at the present rate of deregulation, half the universe will be deregulated in seven to nine years," said McKee. "In 10 to 15 years, if we don't get vacancy decontrol repealed, there will be no rent regulations at all. There will be so few [rent-regulated] tenants [that they] will no longer have the political ability to get the laws renewed for another period of time, which is clearly the real estate strategy."

As tenant advocates see it, the 1997 law has resulted in tens of thousands of high-rent tenants living without right of tenure and without even a right to renew their leases. "Taking steps against the landlord for code violations and repairs could result in the anomalous situation of people moving into high-rent apartments and being afraid" to complain, McKee said.

Suspecting that they might be paying illegal overcharges, hundreds of tenants call Tenants & Neighbors, McKee said, but often tenants in de-regulated apartments are not willing to take action. "People say, 'If I file and lose, he won't renew my lease.'"

The 1997 law also requires that tenants seeking to challenge rents do so within four years of the hike. This four-year statute of limitations is "one of the greatest reforms" of the 1997 law, said Strasburg. Otherwise, he said, new owners could be penalized and forced to pay huge amounts in back rent and damages. "We're not talking about sophisticated owners," he said. "We are talking small property, not deep pockets."

Tenants, however, say the four-year limit can reward landlords who commit deliberate fraud.

Despite the 1997 laws, tenants still have the right to challenge rent hikes—and some succeed.

McKee advises new tenants not to question the status of the apartment before they move in. But immediately after that, the tenant should check the apartment's rent history with the borough office of the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal. If the rent skyrocketed but it looks like extensive renovations have not been done on the apartment, the tenant might have grounds for a rent reduction. Tenant organizations say they often need to hire an engineer to estimate the actual costs of the work and to document that claimed improvements were not made.

THE REVISED CODE

Other state actions have further eroded tenant protections. In December 2000, the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal revised the rent Stabilization Code. Advocates for both tenants and owners agree it helps owners.

One of the most widely publicized provisions could allow owners to evict tenants who charge roommates more than a "proportionate share" — usually half the rent. The code, which has many provisions, also lets landlords increase the rent when a tenant moves out, even if the tenant was there for less than a year. Owners can collect a rent surcharge from tenants who installed their own washing machines, dryers or dishwashers. Owners who want to evict a tenant so they can use his or her apartment for their immediate family can now consider in-laws immediate family.

With these changes, "the executive branch, meaning [Governor George] Pataki, turned the state housing division from an incompetent but fair agency to an incompetent pro-landlord agency," said Sam Himmelstein, a lawyer who represents tenants. "I've seen apartments go overnight from $1500 to $10,000. Who's that helping?"

The answer to that question depends on where you stand in the rent battles of New York.

Related Article:

The Battle Over Rent Regulation by Sam Roseme