The Tragedy And Neglect Of The Staten Island Ferry

The crash of the Staten Island Ferry Andrew Barberi that killed ten people should serve as a warning to New Yorkers that this icon of New York City travel and tourism is in desperate need of attention, and innovation.

Though the tragedy involved a single vessel, it paralyzed the entire ferry system for more than 12 hours. Can you imagine if the Midtown Tunnel or Grand Central Terminal were closed for such a long time? Train stations have numerous platforms and toll plazas have dozens of lanes but, incredibly, Staten Island is only served by a single ferry terminal and single ferry service. Operated by the New York City Department of Transportation, the ferry is an aberration, a municipal anomaly: There is no other transportation system anywhere in New York City that is actually operated by a city agency with city employees.

Other transportation agencies and authorities have had plenty of reason to neglect or ignore the Staten Island Ferry. They see themselves as competing with it, and they are clearly winning; it’s barely a contest. The reality is that ferry ridership (In PDF format) between Staten Island and Manhattan has been declining in recent decades, mostly due to two factors. First, Manhattan as the center of gravity in the region’s job market just isn’t as strong as it used to be, because of the emergence of business districts outside Manhattan, as well as growing work opportunities on Staten Island. The travel patterns of island dwellers has changed, but the route of the ferry, unfortunately, has not.

The second factor in declining Staten Island Ferry ridership is because investments made by other agencies in highways and buses, etc. are paying off handsomely. For instance, in the late 1990s as subway fares were hiked throughout the city, the fares for express buses were cut by $1. This happened just after the ferry fare had been cut $.50 on July 4, 1997. Still, the increased savings on the bus trip has encouraged more riders to shift from boat to bus, leading to another five percent drop in ridership between 2000 and 2001 alone.

In some ways, the city’s operation of the ferry has ignored important trends seen elsewhere in the region’s ferry market. First, the dispersal of the region’s job base to Brooklyn and Jersey City has spurred the creation of seven new ferry landings in these two places in the last decade alone. While Staten Island commuters are migrating to jobs in these places, the city has not kept pace at either promoting or creating ferry linkages between Staten Island and these two growing business districts.

To the city’s credit, there are three new boats on order, including the Guy V. Molinari, which was just launched from the Marinette Shipyard in Wisconsin shipyard last month, and new terminals are under construction at Whitehall Street in Manhattan and St. George in Staten Island. Yet, to its discredit, funding for these investments were not a part of the city’s typical capital budgeting process. They were made financially possible only by a loan secured from the nationwide tobacco settlement of 1998. Had millions of Americans not died from smoking over recent decades, the capital stock of the Staten Island ferry would be still declining.

The city is failing to learn from private operators not just in routes but in ferries themselves. The ones the city is investing in are simply too big, behemoths that cost $40 million and carry 4,500 passengers. They do not help solve the key problems for the Staten Island ferry such as the need for improved night-time service (currently boats only operate hourly), or reduced waiting time between boats. A bigger fleet of smaller boats could give islanders the chance to depart to or from Manhattan every five or seven minutes, and they would surely vote with their MetroCards--if given the opportunity to do so.

To a degree, the service is a prime case of “you get what you pay for.” Since 1997, Staten Island Ferry riders have been paying exactly nothing. It’s the best free ride in the city. More of an accident of history than a conscious public policy, the change in the fare from 50 cents to nothing came with the advent of MetroCard. It would be too expensive, said then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani, to outfit the terminals with MetroCard turnstiles. It would be easier just to let everyone in for free. To critics, this lack of a stable revenue stream has made it too easy for the city not to continue to invest in the system as it should.

Making the Staten Island Ferry part of the MetroCard system may not be very easy. Because it is the only form of transportation that the City of New York itself operates, it does not enjoy the benefits of coordinated scheduling or economy of scale as if it were part of any larger system, such as the MTA.

Ironically, the MTA even uses the Staten Island Ferry in their promotional television ads known as “Going Your Way.” Viewers are treated to sleek trains winding along the bucolic Hudson River, quiet buses whizzing along an Expressway, rapid new subway trains racing across the skyline. The ad closes with a magical only-from-a-helicopter shot showing the big orange boats sliding across the Harbor. Suspiciously absent is the dark blue paint that says “New York City Department of Transportation” on the side of it.

This inclusion of the ferry is particularly ironic given the state of mass transportation on the island. Basically, a web of buses ring and criss-cross the island, while express buses carry passengers to the central business districts. Running north to south is the Staten Island Railroad, itself another stepchild of transportation history. Known as the Staten Island Rapid Transit, it is really anything but rapid, and includes virtually no express service. Particularly aggravating is the common occurrence of northbound trains arriving at St. George only a minute or two after the ferry has departed for Manhattan.

The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge is also operated by the MTA and is widely seen as the biggest cash cow in the MTA’s Bridges and Tunnels system, generating more than $300 million per year. Small wonder then that the MTA under-invests in all other forms of Staten Island transit, choosing instead to grab $7 in tolls from each driver, and pour that money into transit investments that maximize the number of $7 tolls it can collect from vehicles.

The crash of the Andrew Barberiexemplifies how far we’ve isolated ourselves from our greatest natural transportation asset, the waterways. The creation of regularly scheduled ferry service in 1642 launched two centuries of water transit innovation that led to the invention of steam power, the development of a network of canals and waterways that spanned the continent, and the creation of the Clipper ship, which together made New York into a city that is truly a beacon to the best and brightest in the world.

The Staten Island Ferry, as the last vestige of a vast harbor infrastructure which fueled four centuries of growth, could and should symbolize a turning point for the city in leading the way into a new age of innovation on our waterways.

Carter Craft, an urban planner, is program director of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance.

Troubles for Co-op City, and Middle Class Housing in NYC

Photo by Joshua Lutz

“It's a young family's world at Co-op City, the new town being created in N.Y. City," read a promotional poster in the 1960s. "Family-sized apartments at a price you can afford. It's perfect for the family with children… the wide open spaces of a 300-acre residential park (200 city blocks). And not a single interior traffic road. You'll know the youngsters are safe."

More than three decades later, few youngsters are playing in the Greenway, the largest park at the Bronx cooperative housing complex, which has become what social service providers call a "naturally occurring retirement community." Indeed, with more than 8,000 residents over the age of 65, Co-op City is considered the largest such retirement community in the nation. But that is not why children no longer play in its largest park. It is because the Greenway is filled with rows of cars; the park has been turned into a parking lot. It was paved over to provide emergency parking after one of Co-op City's parking garages collapsed and engineers ordered five more closed immediately.

Many other maintenance problems, along with an enormous mortgage debt, have caused Co-op City to go from a symbol of the promise and success of affordable housing in New York to a sign of its woes. While Co-op City crumbles, Mitchell-Lama, the state-sponsored middle class housing program that created it and hundreds of other developments, is eroding in other ways. The city is planning new affordable housing initiatives, but critics say that new buildings will not be able to make up for what is being lost.

"We are in a hemorrhage kind of situation," said Michael McKee, associate director of the New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition. "We are never going to build as much affordable housing as we are going to lose."

DREAM HOUSING; WAKING UP

Co-op City is the largest complex built under the state's Mitchell-Lama program, which ran from 1955 to 1978 and was intended to encourage developers to build housing for the middle class. The state gave developers tax exemptions and low-interest mortgages in exchange for what they hoped would be the public good of affordable housing. At Mitchell-Lama buildings the government has control over rents and co-op prices, and developers have to charge prices that middle class New Yorkers can afford.

The program, named for New York State Senator McNeil Mitchell and State Assemblyman Alfred Lama, is often championed by city planners and housing advocates. "From the point of view of providing affordable, moderately priced housing, it is a smashing success. Can you imagine what the city would be like without the Mitchell-Lama program? For people who work for city government, low to middle income people, this has been an incredible success," said Tom Angotti, a professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College. "I think we should ask ourselves, why isn't Mitchell-Lama being repeated?"

The program, named for New York State Senator McNeil Mitchell and State Assemblyman Alfred Lama, is often championed by city planners and housing advocates. "From the point of view of providing affordable, moderately priced housing, it is a smashing success. Can you imagine what the city would be like without the Mitchell-Lama program? For people who work for city government, low to middle income people, this has been an incredible success," said Tom Angotti, a professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College. "I think we should ask ourselves, why isn't Mitchell-Lama being repeated?"

Others say the reason is clear: it wound up costing taxpayers a great deal more money than anybody had imagined. "The Mitchell-Lama program was supposed to be one in which there were minimal subsidies from state or city funds," said Dick Netzer, professor emeritus of Economics and Public Administration at NYU's Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. "The main reason that the program ended was that it actually required very large subsidies, for some (but not all) projects." The city had tried to finance some of these subsidies by a kind of short-term bonds, Netzer said, which were to be paid off by the mortgage payments on the Mitchell-Lama buildings, but rising interest rates increased the mortgage payments and "project after project defaulted on the required payments. They simply refused to pay what was required." By 1975, there were some $1.8 billion in such bonds, virtually all defaulted. Taxpayers in effect footed some of the resulting bill, and for years afterward, large subsidies continued on some Mitchell-Lama projects, including Co-op City. Meanwhile, Netzer also noted, "there are widespread violations of the income limits set in the Mitchell-Lama law." Thus, despite the "splendid history" of some Mitchell-Lama projects, Netzer concluded, given the exorbitant cost to taxpayers, "it is hard to make much of a case for a new Mitchell-Lama program."

The first of Co-op City's 35 buildings went up in 1968 on the site of an American history theme park called Freedomland USA. The project was designed with its own educational park and other features to keep families from leaving the city for the suburbs, and the price to buy a one-bedroom apartment was just $1,350. So many middle class families left their neighborhoods in the South Bronx to move to the new complex that Co-op City is often said to have signaled the decline of the Grand Concourse.

A one-bedroom apartment in Co-op City now sells for under $6,000, and none of the complex's apartments can be sold to people whose household income is under $18,000 or over $100,000 a year. But while the city-within-a-city continues to be one of the few places where working class New Yorkers can afford to be homeowners, its mortgage debt with the state has climbed to $220 million. And it is falling apart.

REPAIRS AND DEBTS

Every single window needs to be replaced in each of Co-op City's 35 high-rise towers. Each building's cement terraces are crumbling -- wooden fences were installed to protect walkers-by from falling chunks of cement. The elevators need to be overhauled, the brick facades need work and the roofs are in disrepair. The complex's backup generator, which should have kicked in to keep Co-op City running during August's blackout, is broken.

Co-op City's many needed repairs won't be made until the cooperative refinances its debt with the state and gets the money to pay for them. Co-op City stopped making mortgage interest payments in July, saying it simply didn't have the money. Meanwhile, in August the complex's maintenance staff threatened to go on strike, complaining that they are underpaid.

Construction problems have plagued the complex from the beginning, according to Steve Gold, director of residential sales for Riverbay Corporation, which runs the complex. Gas and sewer lines have broken as the land Co-op City was built on settles. The original construction work, overseen by the State Housing Finance Agency, was done poorly, and with substandard materials. And so Co-op City's board has long been arguing with state officials over who should pay for the repairs.

The two sides are in the middle of negotiating a big refinancing package, and say they hope to come to an agreement by the end of the year. As they debate, Co-op City residents worry about when repairs will be made, and about the future of their apartments. Ora Frank moved to her six-room Coop City apartment, with a terrace, in 1971. "We were real pioneers," she said. "But I don't think it ended up the way it started out to be… [These issues] always keep your anxiety up, and a lot of the people who used to fight for things are dead."

And as part of the refinancing, Co-op City will raise maintenance charges, which right now range from $450 to $1,050 a month. "As much as nobody wants to pay more, this will be the first increase since July 1995 and it is going to result in people getting new roofs and elevators," said Gold. "I think that's realistic. I don't believe it is going to be [raised by] a staggering amount."

LEAVING MITCHELL-LAMA

While Co-op City struggles with debt and repairs, other Mitchell-Lama buildings are having troubles of their own. At the converted Mason Mints Candy factory at 20 Henry Street in Brooklyn Heights, all of the tenants are being evicted. They started moving out during the past few weeks. When they are gone, the buildings' new tenants, instead of paying the $600 to $1,000 per apartment that rent cost under the Mitchell-Lama program, will pay amounts similar to the rest of Brooklyn Heights, where an average one-bedroom apartment costs $2,000 a month.

The building's owners are able to do this by taking advantage of a provision in the 1955 Mitchell-Lama bill that says that 20 years after developers receive tax breaks and low interest mortgages to construct a building, they can withdraw from the program by taking financial steps like repaying their mortgages.

The stipulation was included in the bill because lawmakers believed that developers would not have enough incentive to build Mitchell-Lama buildings if they did not have the option to eventually leave the program. Since the last Mitchell-Lama building was finished in 1978, all of the buildings are now eligible to leave.

What happens to tenants after a building leaves Mitchell-Lama depends on when it was built. If the building was finished before January 1, 1974, then all of the apartments will become rent stabilized, and can only increase by the rates set by the city's Rent Guidelines Board. If the building was finished after that date, like the converted Mason Mints Candy factory, owners can charge market rates and force long-term tenants to leave. Legislators and affordable housing advocates have tried unsuccessfully to pass a new law that would make all Mitchell Lama buildings that leave the program become rent stabilized. At 20 Henry Street, the tenants filed a lawsuit seeking to keep their apartments rent-stabilized after the building left Mitchell-Lama. They lost, but decided to appeal.

So far, 52 of the 269 Mitchell-Lama projects built in New York State have left the program, most in the city, according to the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal. (Some Mitchell-Lama buildings are supervised by that state agency, others by the city's Department of Housing Preservation and Development.) Fourteen other projects in New York City have buyouts pending. In some former Mitchell-Lama buildings, like the Ruppert Yorkville Towers on the Upper East Side, tenants have won settlements to be able to purchase their apartments at a reduced rate. And at Waterside Plaza on the East River, tenants eventually came to an agreement with their landlord to keep their rents from being raised to market levels after the city agreed to phase in the landlord's taxes over the next 20 years.

Many housing advocates cheered the Waterside Plaza agreement. But some say that New Yorkers' tax dollars should not pay for keeping a small number of people in $700-a-month midtown apartments. When the agreement between Waterside's tenants and owner was announced in 2001, the New York Post wrote, "Those tax breaks indirectly come out of everyone else's pockets… New York's hugely 'generous' housing policy - be it tax abatements, subsidies, public housing or rent-regulation - discourages tenants from moving out and making apartments available. It also stokes demand - when demand hardly needs stoking."

NEW MIDDLE CLASS HOUSING

Last December, Mayor Michael Bloomberg outlined a plan to try to meet New York City's great demand for housing. The plan would build or renovate 65,000 homes during the next five years. And it includes housing for middle class New Yorkers. According to the Independent Budget Office, about half of the new housing will be for New Yorkers who make between $88,000 and $157,000 a year. Sixteen percent will be for those who make under $50,000 a year.

The mayor's housing initiative is the biggest since Mayor Ed Koch's day. But City Councilmember Gail Brewer responded to the plan by saying that the city should work to preserve Mitchell-Lama buildings and more closely copy the 1955 program. "Here we are as a city trying to provide affordable housing and it already exists. I would opt for more Mitchell-Lamas, if I had my druthers," she told Real Estate Weekly.

McKee, from the New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition, pointed out that through the Mitchell-Lama program, 165,000 homes were built statewide, over 25 years. "And even that was not nearly enough to solve the imbalance between supply and demand," he said, and added that the demand for middle class housing will grow as more Mitchell-Lama buildings go market rate.

CO-OP CITY'S FUTURE

There has even been talk of Co-op City leaving Mitchell-Lama. Some Co-op City board members have argued that instead of renegotiating its mortgage with the state, the complex should leave the Mitchell-Lama program and become a private co-op. This would allow co-op shareholders to sell their apartments for market price. The complex's regulations would make a portion of each shareholder's profit go to Riverbay to use towards paying off the mortgage debt - and making all of the needed repairs.

Last April, Co-op City residents voted to allow the Riverbay Corporation to investigate the prospect of going private. A second, two-thirds majority vote by all of the residents (in which anyone who doesn't vote would be counted as a "no" vote) would be needed to actually leave Mitchell-Lama.

Affordable housing advocates say that because the city has so few apartments that lower and middle class New Yorkers can afford, and is rapidly losing those that do exist, Co-op City's 15,000 homes going private would be a disaster. "Co-Op City should remain affordable not only for people that live in it now, but in the future," said McKee, who added that those who are in favor of privatizing simply "want to profiteer" from the sale of an apartment that they bought at a subsidized rate.

For now, Co-op City has ruled out privatization, but not because the debate is finished: The complex is so strapped for money that it cannot pay to study the pros and cons of leaving Mitchell-Lama.

* * *

Related Links

• CasalsK's Co-op City Page

• David Chessler’s Co-op City Page

• Mitchell Lama Developments With Open Waiting Lists (in pdf format)

• Mitchell Lama Residents Coalition

• New York City's Mitchell Lama Page

• Riverbay Corporation

More Dilapidated Housing, Less Code Enforcement

Just a few blocks up from what was Edgar Allen Poe's cottage in the north Bronx, people are living in a nightmare that might be worthy of one of his tales. And the city's efforts to end it, according to the tenants, are basically useless.

The nightmare is 2874 Grand Concourse, one of the majestic buildings that line the Grand Concourse - majestic at least from the outside.

For almost a year, tenants have been dodging plaster falling from their ceilings and rats in the hallways. They have pleaded with the city to force the landlord to clean up mold, fix a door that allows free access to the roof and replace an antiquated electrical system that leaves many in the dark almost every day. They have caught prostitutes and drug dealers in their hallways conducting business.

City housing inspectors have slapped almost 350 violations on the building. But that has done little to actually get the building repaired - even for the about 80 violations deemed "immediately hazardous" and that theoretically should be corrected with 24 hours.

"They're just coming but nothing's done," said Judith Freeman, the tenant's association president at 2874 Grand Concourse. "There are no results - nothing happens."

Freeman and her neighbors are not the only tenants in the city complaining about passive code enforcement. A new report (In PDF format) by the Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development, co-sponsored by the city's Public Advocate's office, concludes that in the areas that need it most, code enforcement involves little more than writing notes to landlords to please fix their buildings.

The report, released this month and coinciding with hearings on a City Council bill to alter city housing inspections, indicates that people in certain parts of the city are living in dilapidated buildings that are actually getting worse.

The worst housing conditions are in low-income and minority neighborhoods in the South Bronx, Central Brooklyn and Upper Manhattan. The housing code is simply not being enforced strictly where it's needed most, the report concluded.

Astrid Andre, policy director at the Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development and author of the report, said the group had undertaken its report because the organizations making up its membership had different impressions of housing conditions in their areas than officials at the city's housing department. Despite an overall improvement, housing in some areas has not gotten better and, in fact, has gotten worse.

"Our members were telling us there was a stagnation, a deterioration," Andre said. "We just documented what our members were telling us."

The agency that inspects housing in the city, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, downplayed the report.

"Between 1996 and 1999, in the majority of the low income neighborhoods, the numbers were trending in the right direction," said Carol Abrams, assistant commissioner for communications at the department. But when pressed to explain one of the report's findings - an almost 14 percent increase in code violations issued by the agency in the Bronx between 1999 and 2002 - Abrams said she had "no idea."

"There will always be fluctuations," she said. "It's a tenant-driven complaint system."

Overall, Abrams said, the U.S. Census Bureau's Housing Vacancy Survey, conducted every three years, showed the city's housing stock was improving. "The dilapidation rate in 2002 was the lowest than at any other point in the history of the survey," she said.

City Councilmember Joel Rivera, who represents the area where 2874 Grand Concourse sits, said it is unfortunately a building like many others in the Bronx.

"In my district alone, there are a ton of buildings that are in trouble," said Rivera "You don't have to be an inspector to see certain problems.

"The problem in the Bronx is that we have only six full-time inspectors for the entire borough," Rivera said. "The follow-up is not very good because we have so many buildings."

Adding housing inspectors is just one of several recommendations in the new report. Tenants and advocates would also like to see the city housing department impose and collect fines more readily, more aggressively pursue problem landlords and empower tenants by allowing them to petition the department for roof-to-cellar inspections.

Under its current approach, housing inspectors only respond to tenant complaints to its hotline - almost 400,000 annually. But they often walk by glaring problems like broken windows or unlocked front doors because no one complained about them, advocates said.

City Council's new legislation would change that. Intro 400A, as it is called, would allow tenants to petition the city housing department for comprehensive building inspections. The department ought to do such inspections on a cyclical basis in neighborhoods where buildings are dilapidated, the report recommended.

Abrams insisted that the city deploys inspectors in the most efficient fashion, but she declined to respond to questions about that system, instead referring a reporter to the recent testimony of city officials at the City Council public hearing on Intro 400A. The officials said changing the law would not improve things at all.

In their testimony, officials were short on details. They said that inspectors respond to individual complaints and then, through follow up, the complaints are evaluated and analyzed to develop "comprehensive" plans to resolve repair problems.

But Rivera said the department's approach has to change.

"From what I've seen in my own community, the current system does not work," he said. "It's really not the fault of (the city housing department). The administration must invest more in (the city housing department)."

As for the nightmare on the Grand Concourse, its end seems to be approaching, but only after its tenants organized, hauled the landlord into court - and got Councilmember Rivera, their representative, and Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum to visit the building with an entourage of reporters in tow.

Their months of complaints to the city housing department had only led to a $500 fine of the landlord for heat and hot water problems, despite periods as long as a week last winter without any heat or hot water. A Housing Court case for repairs is ongoing and Freeman, the tenant's association president, said she is hoping that the building is taken over by an independent administrator who will apply rents to making repairs. The landlord, Moshe Pillar, could not be reached for comment.

"I really think the only reason they are coming back to follow up now is because" Rivera and the public advocate got involved, Freeman said. "We got the $500 fine, but think of all the months we've got to go."

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations.

The Foundation Fundraising Blues

In a city notorious for unscrupulous landlords and the unchecked power of corporations, there is one group that easily inspires the most angry whispering among the heads of many community organizations -- philanthropic foundations.

Tales are told and told again about program officers who don't understand the work they fund; about community groups being made to dance on strings by their foundation patrons; about the capricious way that foundations dole out grants, particularly to small organizations.

For years critics of foundation practices have argued that because foundation dollars are tax-sheltered monies, much of which would otherwise be sitting in the US Treasury, the public has a right to exercise greater control over foundation grant making. Indeed, members of Congress are attempting to increase the amount that foundations are legally mandated to give away every year, though their efforts are meeting resistance. And groups like the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, which was created in 1976, promote "public accountability and transparencies among foundations".

But putting aside the issue of right or wrong, some have long recognized that foundations would simply be more effective in their grant making - whether it be an effort to create more jobs, build more housing, improve public education or strengthen families - if they were more sensitive to the day-to-day realities of the groups and neighborhoods they fund.

In his book American Foundations, which calls for a "foundation anti-trust act" that would break up mega-foundations and make the rest more democratic, Mark Dowie cites a recommendation made way back in 1913 by Jerome Greene. who was later to become secretary of the Rockefeller Foundation. Although he was apparently ignored at the time, Greene proposed the forming of a "public council" to run foundations, as opposed to the "patrician boards that ran foundations at the time", Dowie writes.

Almost a century after Greene proposed a more democratic way of running foundations, most foundations are still highly cloistered, self-perpetuating, elite institutions that seem to answer to no one but themselves. Most foundations function as the vision of one rich white man or family. Peter Goldmark, the former president of Rockefeller said that a typical foundation usually tries to "change some aspect of the larger society in accordance with a view held only by a minority or even a single person. Its job is not to reflect, protect or govern according to a majority."

But with the government's role in areas like housing production, small business improvement and social programs waning in New York, the collective power and influence that foundations play in shaping organized responses to poverty and issues of social justice, will only increase. So, which one of us is going to tell the emperor when he walks down the street that his butt is hanging out? With so much at stake, is it possible for community development organizations to have a truly honest exchange with the hand that feeds them without that hand feeling bitten?

RELATIONSHIP FULL OF IRONIES

To be fair, I have yet to find a way to build social justice institutions using a for-profit or individual donor model. The non-profit organizations with which I have been affiliated over the past 15 years have been sustained by foundations, beneficiaries of hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of foundation grants. It would be hard to ignore the incredible social good that foundations generate in New York and the world.

But it's also hard to ignore some of the ironies of fundraising in a community development environment. For instance, many foundations, when setting their funding criteria, will place premium value on things like democratic structures, organizational accountability and collaborations with other organizations, without ever observing those practices within their own institutions. My favorites are the foundations who patronizingly dictate that grantees maintain "involuntarily poor people" on their board, while themselves maintaining institutions with little if any input from low-income people.

In just one textbook example of how community change foundations often don't want to live in the world they themselves promote, two years ago a prominent national foundation that sponsors confrontational, direct-action organizing in New York and abroad once punished organizations by withholding hundreds of thousands in grant dollars. Why? Because the organizations had the temerity to target the foundation itself in a welfare reform protest. John Ashcroft couldn't have issued a more chilling gag order.

Foundations move at their own schedules and idiosyncratic discretion and are notorious for shifting leaders and development strategies like pieces on a chess board. They routinely generate fads in community development practice and anoint those they consider to be the rising stars while unilaterally dictating to neighborhoods and organizations what models of development should be pursued. Another neat trick is when foundations do the exact opposite - sit on the sidelines for 12 or 18 months, not making any new grants because they are "rethinking" their funding criteria, seemingly oblivious to the fact that the world is still spinning.

The result is that grassroots organizations, especially those without government contracts or the capacity to sustain non-grant fundraising campaigns, are constantly kept anxiety-stricken, off balance and insecure. They function in a year round game of financial hide-and-seek, rarely able to conduct long-term planning with confidence.

The most fundamental irony of all is the notion that foundations involved in community development purport to support campaigns and efforts that help people level the socio-economic playing field and exert more control over their lives. And yet it is precisely the disparity of power between foundations and the organizations they fund, and the lack of control that organizations exert, that is so dispiriting to community builders.

One of the greatest threats to community development work is the indulgence of our own propaganda. In my experience, most foundations involved in community building would rather live in a bubble and believe all the blurbs about their grantees that they put in their annual reports or their press clippings, than accept the fact that community development is a protracted, three steps forward, four steps backward, grind being done with the ground shifting beneath your feet.

A DIFFERENT APPROACH

Despite the reasoned arguments of philanthropy reformists like Dowie, foundations are not likely to voluntarily give up power or make themselves more accountable to grassroots voices.

Bob Brothwell, the president emeritus of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and a pioneering veteran of the foundation accountability debate, insists that "calls for accountability always go nowhere". Instead Brothwell, who in 2000 conducted a study of foundation funding of grassroots organizations maintains that we should "talk about what really works, building relationships between foundations and organizations, relationships that are inclined to support" community organizations. Brothwell described to me the elements of successful "partnerships" between foundations and organization that he discovered in his study: Intimate, two-way, committed investments of time, communication and resources that inherently include a modest degree of power sharing by the foundation.

What stands out above all else in Brothwell's model partnership, is a framework for an on-going working dialogue between a foundation and an organization, an exchange in which the foundation is more committed to the long-term success of the organization than what the organization is able to achieve over a given year. This kind of relationship entails patient, multi-year, institution-strengthening, grant making - not a year-to-year, Pavlovian reward.

This kind of partnership means making grants to the entire organization, not just individual programs. It means frequent conversations where organizations are free to discuss their vulnerabilities and the details of their challenges, without fear that their words will be used against them. It means site visits and interactions where organizations are not expected to exploitatively showcase their "success story" members like show ponies or talking monkeys.

Its a relationship committed to sustaining a stable environment in which community development practitioners can spend more time serving their constituents than reading the funding tea leaves or figuring out where the nut is buried in the next funding shell game. I will even go as far as suggesting that it means letting organizations and local players set funding priorities that fit their communities.

I have certainly worked with a handful of program officers and foundations who maintain exemplary, responsive relationships with their grantees. The most progressive and conscientious foundations even have decision-making advisory committees made up almost entirely of grantees, community leaders and the like. But we all could stand to be shaken out of our complacency and trade places with one another. I would challenge any foundation official, even those who come from the community development and activist ranks, to spend a month in the trenches juggling the demands of a grassroots community development organization. By the same token, self-righteous, know-it-alls like me and other community development professionals should spend some time in the shoes of a typical foundation official to understand how difficult it is to meet the pressures of a foundation mission while sifting through hundreds of applications and trying to responsibly manage relationships with community development organizations.

Maybe we can't expect a wholesale change in the way foundations treat community organizations, but perhaps a few brave, philanthropic leaders could publicly model and promote a new kind of relationship between foundations and community organizations. Of course this would be a long-term process that would require independent monitoring, evaluation and an aggressive advocacy campaign to trumpet the results. All the project needs is a foundation to fund it.

Mark Winston Griffith, a writer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Essence and Spin, is also founder of the non-profit Central Brooklyn Partnership, which organizes people to build economic power.

Staten Island Awaits Its Turn

Few people know that when Giovanni da Verrazano sailed into New York Harbor in 1524 he first landed on Staten Island. Though the Island was possibly the first place that European explorers arrived on land, Staten Island often seems last when it comes to implementing public policies that improve the quality of city living. Staten Island has all the problems facing the rest of the city--unplanned and uncoordinated growth, traffic congestion, and disappearing open and public space.

But nestled in this borough bounded by bays and kills are a few model solutions as well. The Staten Island Bluebelt, for instance, uses wetlands to capture stormwater runoff and, with nature's help, treats this tainted water for half the cost of the mechanical treatment that is necessary in more densely paved parts of the city. The Island has the only ferry in New York City that truly functions as public transportation: it runs 24 hours a day and is free (yes, FREE) to all riders. Just north of Fresh Kills landfill sits a paper re-manufacturing plant that takes a portion of the city's solid waste stream and uses these scraps to produce marketable goods, in large quantities. Looking ahead, the island is poised to become a choice borough if it can capitalize on its most famous assets, particularly its geographic proximity to (gasp!) New Jersey.

The island nature creates an insular feeling among residents and visitors alike. When viewed with Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan, it seems to many people that only Staten is an island, when in fact four of the five boroughs really rest on islands as well. This psychological sense of non-belonging last culminated in a referendum question in 1993 in which islanders voted to form their own city, though the State Legislature never approved the secession. Three years later Fresh Kills landfill closed.

For a half century Fresh Kills landfill was both the largest physical landmark as well as psychological burden which islanders carried with them wherever they went. The closure of the landfill, while a mental boon for islanders and a boost to property owners, has not yet brought about a sustainable or even sane solid waste management policy for the city. But we are getting closer. Recently, officials from VISY paper organized a tour for borough leadership of a solid waste handling and sorting facility in Germany that is as close to the state of the art as anything in existence in the U.S. While garbage is not pretty business, the reality is that it is New York City's largest export as well as an expense item that accounts for nearly three percent of the city's annual budget. It is a problem we will have to solve to survive as a city.

In many ways the landfill's swing from open to closed is characteristic of the highly politicized nature of land use decision-making that afflicts US cities with the urban planning equivalent of bipolar disorder: now it is wide open, now it is sealed shut. Rarely is there any in-between. But fortunately for New York there is Staten Island.

The latest instance of this bi-polar disorder was diagnosed this past July, when Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the creation of a task force to examine "growth management" on the island. Often derisively referred to as an overdevelopment task force, this entire effort, and the land use debate on the island, should instead be framed as an under-transit task force. It is a well-known fact that islanders feel alienated from much of the rest of the city. While they have only two linkages (a bridge to Brooklyn and a ferry to Manhattan) they have three connections to New Jersey in the form of the Outerbridge, the Goethals, and the Bayonne Bridges.

But as the population of the island has doubled since the time the Verrazano Bridge opened in 1964, the island has not added any new physical connections to surrounding boroughs or cities. Sure new funds are being tapped for additional express buses to Manhattan, but what the island needs desperately are new transit options that reduce pressures on the bridge and ferry crossing already jammed to capacity. For instance, the congestion on the Staten Island Expressway will not be solved with widened on-and off ramps here and there, but if there were other options such as passenger ferries or even truck ferries between New Jersey and Brooklyn the commuters and goods would actually have an option of how to travel.

A borough of nearly half a million people needs better transit not just between boroughs but within Staten Island itself. With rail lines along the west and north shores of the island now sitting idle for decades, how long can it be before policymakers realize that the solution to the island's development pressures woes are the mostly intact rail rights-of-way that are staring them in the face?

Perhaps the most visionary thinking for Staten Island has originated outside the state. Just a couple of years ago the executive director of New Jersey Transit suggested that the new Hudson Bergen Light Rail that now ends just across the Bayonne Bridge might someday pass over the Bayonne Bridge and all the way down to Tottenville at the southern tip of Staten Island. Such imaginative and apolitical thinking is what this congested island will need to prosper in the future. Beholden to a city and state so fixated on Lower Manhattan, perhaps Staten Islanders would be better off taking their case to Trenton.

Carter Craft, an urban planner, is program director of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance.

A Frustrating Apartment Search

Leaving New YorkWhile some New Yorkers are leaving the city, citing bad schools, high housing costs or the daily stresses of urban life, analysts debate whether the exodus is anything alarming or unusual, and what to do about it.Why New Yorkers Are Leaving: The City Is Too Expensive by E.J. McMahon City Schools and Housing Are Inadequate by David Kallick New Yorkers Who Left: Allison Woods Struggling with Strollers and Schools David Bassine Fear of Terrorism Stefan Kochi Bad for Business |

What finally took me over the edge was the act of going out and looking for an apartment. I recently got married and had a son, so I needed to find a new place. I had lived in the same apartment for 26 years - my whole life. When I actually started looking I saw how hard it was to find a place to live. I only found one good deal, but even that good deal was a bad one. It was on Fresh Pond Road in Queens, right next to the subway station. Besides the fact that the subway was so loud that it would wake my baby, the floor slanted.

That was the last straw. I have a friend from Brooklyn who lives in Maryland. He had told me about how things were for him there. When he left, he struggled, but now he is a lot more comfortable. And he has kids too. So I said, "Why don't we try it?" My wife, my son and I moved down on July 4.

Maryland is different, and I am having issues trying to get used to it. The slower pace of everything is hard to adjust to. Compared to New York, anything is slow, but this is really slow. I get bored. My wife likes it less than I do, because she is at home taking care of our son all day. We don't get out much because we don't have transportation. No outdoorsy things -- really the only place we can walk to is the mall. Or we go to my friend's house. If I didn't have him out here, I wouldn't have come.

I have been back to New York once since the move, and it wasn't that great. My neighborhood - Williamsburg just outside the gentrified part -- is stagnant.

I felt that way before we moved, but when I came back, the feeling was magnified. It is the feeling that every day is just the same -- it never changes. When you are young, you hang out, play basketball -- all types of things to keep yourself busy. But when you grow up and everyone you know is older, people don't want to do anything. There's nothing to do, the basketball court is empty, no one is around. It's weird.

The way I look at it, if I can't live in Manhattan, then I won't live in New York. I'm from Brooklyn, but there's nothing good in Brooklyn unless you have Manhattan money. If I have to pay Manhattan money to live in a nice place in Brooklyn, I might as well live in Manhattan - or Maryland.

Rondrae Hunter was born in Brooklyn and moved out of New York in 2003. For three years, he was office administrator of Citizens Union Foundation, the publisher of Gotham Gazette.

To Keep People, Improve Schools And Housing

|

Leaving New York While some New Yorkers are leaving the city, citing bad schools, high housing costs or the daily stresses of urban life, analysts debate whether the exodus is anything alarming or unusual, and what to do about it. Why New Yorkers Are Leaving: The City Is Too Expensive by E.J. McMahon City Schools and Housing Are Inadequate by David Kallick New Yorkers Who Left: Rondrae Hunter A Frustrating Apartment Search Allison Woods Struggling with Strollers and Schools David Bassine Fear of Terrorism Stefan Kochi Bad for Business |

The combined effect of people coming to and leaving the city, factoring in "natural increase" (more births than deaths), resulted in an expansion of the population by about 3.5 percent in the 1980s, and a further increase of 9.4 percent between 1990 and 2000. For the period since 2000 the data is incomplete, but early signs seem to show population between 2000 and 2002 holding about steady.

People leave the city for all kinds of reasons, including job opportunities, retirement, family and friends. These are all positive events in people's lives; population loss for these reasons should not be seen as negative.

More worrisome, however, is that roughly half the departing population stays in the metropolitan area, but moves to the ever-expanding suburbs of the city. Some movement in this direction is perfectly healthy. But the city should not be complacent about people who may be "voting with their feet," and the region has reason to be concerned about the resulting suburban sprawl.

There is little hard data on why people move to the suburbs. Conservatives often say it is taxes. More likely explanations, however, are the inadequacy of New York City schools and housing. A recently released poll by the Drum Major Institute points in this direction. When New York City voters were asked about what personally worried them, 82 percent said the quality of public schools, top answer, and 68 percent said affordable housing. Health insurance and making ends meet also ranked high; the level of taxation did not.

This is very far from the "white flight" the city experienced in the 1970s. "First of all, how could you have white flight from a city with our composition?" asks Joseph Salvo, director of the population division at the Department of City Planning. "If you look at who's leaving, you have white population, but there are also black and Hispanic and Asian."

Whatever their ethnicity, many New Yorkers who are leaving do so in search of more space and better schools.

IT'S NOT BECAUSE OF TAXES

A convoluted argument has surfaced recently that ties together a narrow interpretation of the recently released census data and a reflexive tendency for conservatives to pin everything on taxes.

"New Yorkers Fleeing City, State," hyped the front-page headline in the New York Sun on September 2. The New York Post followed in an editorial the next day, saying "more Americans moved out of the city than moved in between 1995 and 2000," and that New York State "is losing residents faster than any of the other 49."

Before taking a breath to analyze the data, both papers had a ready rationale. "High taxes may be fueling" the trend, suggested the Post. High taxes, housing policies, and unions are the culprits named in the Sun and in the article this week in Gotham Gazette by Manhattan Institute analyst E.J. McMahon.

First of all: population increased significantly throughout the 1990s. But the county-to-county census data the newspapers reported includes only domestic migration. It excludes from the picture international migration.

"Like many large cities in this country, we shed more people than we gain through domestic migration," explains Salvo from City Planning. "What makes New York different is that we have the benefit of a large number of immigrants." Immigration, plus natural increase (more births than deaths), are the reasons the city has seen an overall increase in population at the same time as it experiences a net loss in domestic migration.

Indeed, says Salvo, the net loss the city experiences in domestic migration is not a new trend. It has been the status quo "since at least the middle of the last century."

The pernicious argument that high taxes are the root of all evil is far afield in relation to population change.

"If high taxes caused out-migration, why did upstate counties -- with some of the state's lowest combined taxes -- experience significant losses of total population, while New York City, with the state's highest combined tax, grew at a fast clip?" asks Lava Thimmayya, co-author of the Fiscal Policy Institute's report, State of Working New York 2003. Indeed, the areas with highest taxes also showed the strongest economic growth, notes Thimmayya.

Even billionaire Mayor Mike Bloomberg seems to agree that taxes don't push people out. Earlier this year, when arguing for a tax hike to close the budget gap, Bloomberg said: "I don't believe that people will leave this city because of higher taxes." He then went on to say, "I do believe they would leave this city very quickly because of lower services."

Over and over, the perception of problems in the schools, the lack of affordable housing, and downturns in the job market emerge as the key "negative" factors that push people out of New York. Taxes don't even rate on the scale.

The message to city officials from ex-urbanites is: make real steps to improve city schools, expand the supply of truly affordable housing, and then let's talk.

David Kallick is senior fellow of the Fiscal Policy Institute.

Noise Pollution: A City Planning Problem

The city's Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) recently announced an updating of its regulations against noise and an enforcement blitz in 25 noisy neighborhoods. (See David Seifman, "The Noise Cops are Coming," New York Post, 9/8/03). Of all the things New Yorkers complain about, noise tops the list. We complain about loud music, cars, trucks, buses, construction, planes, and subway trains. Sometimes we just don't like to hear our neighbors talk, or we hate the music they listen to. The latest auditory annoyance is the scooter, which is illegal to operate in the first place but a great noisemaker for young people who want attention.

The city's incessant street noises aren't just annoying. They can cause temporary hearing loss, contribute to stress and sleep loss, and over a long period of time cause permanent damage to your health. Add to the toll taken by public noise are the many abuses of private noise, like the music machines that people wire themselves up to while plodding half consciously through the city's noisy streets.

Enforcement alone won't get rid of noise pollution. Parking tickets don't stop illegal parking, but only make it costlier. Sanitation tickets haven't stopped dumping. And it's going to be hard to stop noise pollution by depending only on enforcement of the laws. Especially with its reduced budget, the city will have trouble finding enough officers to crack down on all the city's auditory assaults. It might be cheaper to hand out earplugs or cell phones to everyone, but who wants to live in a city of spaced out zombies who bump into everyone else and are targets for cars and trucks?

Needed: A Sustainable Strategy

In the long run the basic problem is it to prevent noise before it occurs. This requires a strategy that goes after the sources of noise before they harm people, not after the fact. Despite the tireless efforts of many committed professionals that deal with the city's environmental regulations, city government has adopted no such plan. Slapping fines is a short-term tactic that doesn't rest on a strategy that can sustain a better environment in the long run.

To begin with, the city doesn't adequately regulate new development in a way that can create noise-free environments. The city's land use regulations require that any major new development that is subject to city's land use review procedure undergo an environmental assessment. This should consider potential noise levels produced by the development and the noise levels that the project's occupants are expected to experience. If it's found that the new development may have a negative impact on noise levels, the developer may volunteer to implement measures to reduce or counteract the noise. For example, if a new apartment building is on a busy avenue with heavy traffic, the developer will typically agree to put in triple-pane windows. But this just blocks the noise for some while everyone else on the street has to suffer the traffic noise.

The city's Zoning Resolution was designed to prevent certain types of noise- producing activities from locating near residents. But these regulations were made over forty years ago, before the onset of environmental regulations. A revamping of the zoning regulations is long overdue. The new regulations would, however, only affect new development because of the city's long-lasting practice of "grandfathering" for eternity development that is deemed to go against the public interest. Revised regulations would do little to address most of the city's current noise problems.

Street Noise

Thick windows and quiet neighbors in new apartments won't solve probably the biggest noise problem -- street noise. This requires another set of strategies to deal with the excessive volume of traffic on the streets. By improving the overall environment for people who walk, we can address the problems of noise, air pollution and safety, all of which are serious public health problems. Unfortunately, the city's traffic policy is mostly geared to moving more cars and trucks through the streets, which only creates more noise. It's really quite simple: less traffic, less noise and a better environment.

The benefits of traffic reduction would be especially great in congested areas like Midtown Manhattan, where fumes are furious and there's a honk a minute. Trucks and buses should have improved equipment to buffer noise. Truck deliveries could be limited to times of day when there are fewer pedestrians, a common practice in other cities around the world.

Subway Noise

Another of the city's noisiest sites is the subway. But enforcers from the Department of Environmental Protection can't slap violations on one of the city's biggest polluters, the Metropolitan Transit Authority. The MTA is one of those untouchable state authorities that seems to think first about satisfying its bondholders and keeping its hands in its customer's pockets. Over the last twenty years the MTA has dramatically improved track conditions, especially at busy stations, reducing many of the worst noise hazards. But frequent subway riders know all too well that they can still come out of the subway with their heads spinning from shrieking brakes at stations or screeching wheels at curves. MTA buses are also notoriously loud and polluting, and the authority further chooses to concentrate its bus garages in low-income communities like Harlem, where the sheer volume of bus traffic is enough to make neighbors scream.

Another big noise generator is air traffic. Neighborhoods around airports live daily with the noise and vibrations of planes taking off and landing.

In sum, the city's transportation system, both above and below ground, is the biggest contributor to noise pollution. It's time to focus not just on moving the greatest number of vehicles as fast as possible, but in moving them without endangering the physical and mental health of city residents and workers. Actually cars move far fewer people than public transit and pollute far more, so the benefits of traffic reduction are much greater. Our streets, sidewalks and subways are our most utilized public spaces, but we have no plan for improving the quality of life for the vast majority of people who pass through these spaces on foot. If the city really wants to address the quality of life in the noisiest neighborhoods, they'll have to do a lot more than send out the ticket-writers.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Planners Network Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

Abandonment In 2003

Â

A residential building is abandoned almost every day in New York City. Its owners stops paying real estate taxes, or water or sewer charges, or refuses to make needed repairs. Most abandoned buildings are occupied, and tenants are left to fend for themselves.

While the city goes to great lengths to prevent abandonment – offering educational seminars, installment plans and low-interest loans to owners whose buildings are in distress – it still sees hundreds of properties each year whose owners have essentially walked away. When all other efforts fail, these properties become part of the city’s Third Party Transfer Program, and are placed into responsible new hands.

First, the city convinces a court that the owners have been too long negligent. Then owners have a few months to make amends – by paying the tax arrears and adhering to a repair schedule. If they don’t, the city transfers the properties to a holding company which helps new owners, selected by the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development and approved by the City Council, plan rehabilitation and financing. Within a year, the holding company releases the property to the new owners.

So far, 214 properties have passed through the program, with another 100 to be transferred in November. More than 300 are scheduled for the next round. City administrators are pleased with the progress.

“Buildings are flowing through the program nicely,” said Michael Bosnick, assistant commissioner of the anti-abandonment program of the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. “And we certainly don’t hear a lot of tenant complaints.”

The program has even won a few “good government” awards, and it is undoubtedly better than the system in place in the 1970s and 80s when a wave of abandonment orphaned more than 355,000 housing units. The city took over their management, becoming its own biggest slumlord, since abandoned housing tends to have the worst maintenance problems and the poorest tenants.

Owning these apartments turned out to be very costly for the city and Mayor Rudy Giuliani wanted to change the system. So the city started selling off the properties (in pdf format) and is down to fewer than 6,500. And a number of new mechanisms were put into place to ensure that no new properties would come under city management.

Now, anti-abandonment measures kick in at the first hint of trouble – a few quarters of tax lateness or a disturbing trend of tenant calls to 311. The city contracts with “neighborhood preservation consultants,” who reach out to troubled property owners. The consultants, often pre-existing not-for-profit housing groups, might help owners apply for loans so they can pay for repairs or conduct seminars to educate owners about managing and maintaining their properties.

Those who stay on the path to abandonment, are often one of two groups, says Lisa Nicole Grist, executive director of Neighbors Helping Neighbors, a neighborhood preservation consultant in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. They may have inherited a building that they cannot handle, financially, or physically. Or, they may have owned the building for awhile then faced a drastic life change– illness, infirmity, or a financial crisis – and are suddenly in over their heads.

Troubled owners of non-distressed properties may face the sale of their tax lien to private investors who try to collect or else foreclose on the properties. Owners whose buildings need major maintenance can be hauled into court and ordered to commit to a repair schedule, or a judge can appoint an administrator to collect rents and apply them to maintenance. And for the worst case scenarios, for distressed properties that also have tax liens, the city can seek in rem tax foreclosure and place them in the Third Party Transfer program.

About 75 percent of owners who stand to lose their property to transfer manage to pay their debts and make the repairs. The remaining 25 percent who do lose their properties, “fall into two categories,” said Bosnick. “Those who have already given up on the properties, and those who are really not happy about losing them.” Unlike in the 1970s and 1980s, when widespread abandonment corresponded to a declining population and fewer jobs, today’s abandoners tend to be relative newcomers to the market and owners of smaller buildings (especially those containing one to four units.) With no experience in housing management, many are overwhelmed by the city’s complex housing regulations and the economic realities of smaller buildings.

“Smaller buildings are the most challenging to run,” says Brosnick. “If two of your tenants aren’t paying rent, and you only have eight units, you’re in trouble. But if you have a 25-unit building, you have more leeway.”

Still, he said, “housing has become a much more valuable commodity, even at the lower end of the market, so now you see less outright abandonment. But at the bottom of the market, you see a tendency to cut back on services, to get behind on maintenance and maybe also on taxes.”

In Sunset Park, Brooklyn, Neighbors Helping Neighbors often encounters “buildings in which the tenants feel like they have been abandoned, because the owner has stopped providing services,” says Grist. “In fact, owners have no intention of walking away; they just hope the tenants will walk away.”

Tales of landlords angling for tenants with deeper pockets are legion, but New York’s aging housing stock – more than 60 percent of residential buildings were built before 1947 – often needs costly repairs. And with property taxes on the rise too, the anti-abandonment office may soon be busier than ever.

Rebecca Webber is a journalist who has covered housing issues for Gotham Gazette since July 2000.

What Made The Blackout Inevitable

Related Articles: My Own Private Blackout Mike Misner explains why it was in some ways a good thing -- blackouts make environmentalists such as himself feel less guilty. Sep 15, 2003. After The Blackout -- Going Back To The Experts New Yorkers were among the victims of the largest blackout in the nation's history - and it had nothing to do with the research Con Edison was conducting. Aug 18, 2003. Studying How to Avoid Blackouts Con Edison has opened a new research lab -- a mock manhole in the Bronx -- to study the problem. But critics say it could do more. Originally published just three days before the Blackout of 2003 -- Aug 11, 2003. Related Links: • Blackout 2003 - Gotham Gazette's Coverage • Blackout Message Board |

Our system of electricity, begun a century ago, consists of large centralized power plants and a complex network of cables and wires called a transmission "grid" to bring the power to customers. A huge number of components in the system interact with each other, sometimes in ways that engineers do not anticipate.

In any system of such size and complexity, failures are likely to occur, as Charles Perrow pointed out in his 1984 classic, Normal Accidents: Living With High-Risk Technologies, in which he explained why failures are common in such systems as the chemical and nuclear power industries.

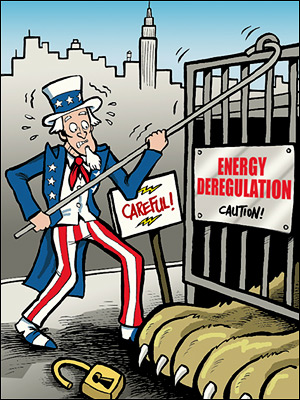

But it is not just a question of size. Ironically, part of the problem rests with the very laws set up over the last couple of decades to improve the delivery of electricity.

POWER TO PEOPLE

In 1882, Thomas Edison built the world's first electrical generating plant on Pearl Street in New York City's financial district. The plant powered the electric lights in local businesses. The era of electric distribution followed shortly after. In 1896 electricity created by water turbines at Niagara Falls was transmitted 20 miles away to the city of Buffalo where it powered lights and trolleys.

For nearly a century, most electric power has been created by large power plants built near cities where demand is the highest, and then distributed through the grid system of transmission lines, which connects power plants together and connects plants to buildings and homes.

Historically, monopoly utilities built these transmission lines to connect one power company to another. The lines also provided emergency power if a neighboring area lost power from one of its generators.

The system was supported and promoted by a web of federal and state government regulations, which determined how energy could be created, where it could be distributed, and at what rates it could be sold. These laws were created not only to protect consumers, but also to ensure that utility companies made enough money and attracted enough investors in order to provide electricity to consumers.

As energy prices rose in the 1970's and 1980's, policy makers began to believe that electric utilities -- like the airlines, telecommunications, and trucking industries, which were also governed by federal and state regulations -- could produce better products at cheaper prices if the system were regulated less, allowing it to operate under free-market principles and new technologies.

In 1992, President George Bush signed a new energy policy into law. Independent companies could now sell power to distant cities and use transmission lines of several utility companies to deliver the power.

As deregulation gained momentum, the relationships between former monopoly utilities became strained as they started competing against each other. Some power generators now try to sell power to far away states where they can get the highest prices.

CALIFORNIA'S LEGACY

In 1996, California became the first major state to revise its regulation of electric power to permit consumers to choose their own electricity provider.

The promise of competition stemmed in part from the disparate prices paid by customers across the nation. Under regulatory practices, state commissions approved the rates paid by customers based on the value of the equipment used to generate, transmit, and distribute electricity along with the cost of other expenses such as fuel. In some parts of the country, particularly California and New England, rates were high because of the high cost of power plant construction and fuel.

In 1996, the California legislature passed a bill that would allow retail customers to choose their energy supplier by January of 1998. More than 200 companies registered to resell wholesale electricity to residential and business consumers, and residential customers saw an immediate 10 percent reduction in rates.

Due to a number of factors, including power companies looking to sell their power elsewhere, a drought in the Northwest, rising natural gas prices, and the lack of long term contracts, wholesale prices rose more than five times the previous amount by May of 2000

As a result, the California Independent System Operator imposed price caps, meaning that the generators of power could not ask for prices above a certain level. Upset at the caps, power generating companies often sold power out of the state, thus reducing supply for customers in the state. Some companies found themselves unable to compete and went bankrupt.

Consumers also suffered. Because of inadequate power supplies, "rolling blackouts" of 60 to 90 minutes became necessary so electricity could be rationed around the state. In the first six months of 2001, California experienced rolling blackouts 38 times.

After the events in California, lawmakers became wary about how to proceed. Some states have moved toward more regulations, others have moved toward less.

The electric utility industry still remains in flux. This uncertainty puts investors and utility managers in a bad position, since they do not know what is going to happen in the future. Independent generating companies also hesitate to act because they do not know if they will be operating in a competitive market, a more regulated environment, or some mixture of the two.

THE 2003 BLACKOUT

While the details of the recent power failure that shut down more than 100 power plants in New York, Ohio, Michigan and Canada are still being investigated, it is clear that the current confusion over how the nation's energy industry should or should not be regulated played a key role in the largest blackout in the nation's history.

Investigators say there was a failure in the transmission system. And, thanks to deregulation, there is growing concern and confusion over how these systems should be monitored and who should pay for them.

In some states, the transmission system is run by the state agency, an Independent System Operator. While the utilities companies own the lines themselves, they do not have control over them and are not eager to invest billions of dollars into them.

In other states, the companies own the transmission lines, but the rates remain regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, so that they cannot make as much as they could if they built new power plants and could sell the power at market rates.

Before deregulation, the North American Electric Reliability Council established voluntary rules to deal with problems with the grid, helping to ensure that a problem did not cascade through the entire system. With the recent blackout, many have speculated that some utilities may not have been following these voluntary guidelines due to competitive pressure.

PREVENTING FUTURE BLACKOUTS

I hope that the current investigations into the 2003 blackout will lead to broad solutions beyond simply beefing up the existing system and building more power lines.

We are not going to get rid of the big power plants and transmission lines that we now have, but to minimize the possibility of widespread blackouts in the future, the country may need to retreat from the traditional paradigm of the electric utility system.

Between 1907 and 1980s, the paradigm consisted of regulated, regional utility companies systems that built large, centralized power stations and transmitted electricity through power lines to customers. We still live with a system built when these types of centralized power plants made sense.

But it may make more sense now to begin moving (at least partially) toward a decentralized system that contains small scale, modular and diverse types of equipment that produce power close to cities or even within buildings that use a lot of electricity.

Employing diesel generators, or better yet - from an environmental point of view - fuel cells, micro turbines, wind turbines, and photovoltaic cells, such a system would reduce the strain on the existing grid by providing power to users without depending on transmission lines at all.

It would also allow big uses of power to continue operating if parts of the grid failed, due to problems on the grid or to a terrorist attack.

Finally, it would give the decentralized producers of power an opportunity to sell surplus power to other customers through a local distribution network.

While technical challenges remain for implementing such a distributed system, it may provide at least part of the solution for dealing with a utility system that appears to be reaching technical and managerial limits.

Richard F. Hirsh is a professor of history of technology and science and technology studies at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia. He authored a series of essays for the Smithsonian Institution's website on the history of deregulation and the book Power Loss: The Origins of Deregulation and Restructuring in the American Electric Utility System.

Related Articles

My Own Private Blackout

Mike Misner explains why it was in some ways a good thing -- blackouts make environmentalists such as himself feel less guilty. Sep 15, 2003.

After The Blackout -- Going Back To The Experts

New Yorkers were among the victims of the largest blackout in the nation's history - and it had nothing to do with the research Con Edison was conducting. Aug 18, 2003.

Studying How to Avoid Blackouts

Con Edison has opened a new research lab -- a mock manhole in the Bronx -- to study the problem. But critics say it could do more. Originally published just three days before the Blackout of 2003 -- Aug 11, 2003.

Related Links

• Blackout 2003 - Gotham Gazette's Coverage

• Blackout Message Board

My Own Private Blackout

I'm not chaining myself to trees, but I understand that everything I do affects the environment, and it makes me feel guilty.

|

When the largest blackout in the nation's history occurred, it did not bother me too much. My neighbor and I already had had our own private, self-induced blackout. Living in similar apartments, we had a contest for the lowest electricity bill. The loser would pay the winner's bill and the winner would enjoy bragging rights.

I went without air conditioning, a definite power hog, opting instead for a ceiling fan at its slowest speed. My pre-war apartment runs cool, but at times during the summer I felt like a thin crust pizza in a brick oven.

Yet I persisted. The TV, radio, stereo, computer, and cell phone re-charger were unplugged so as not to leak electricity. There were moments when I sat in the dark, dressing in twilight, and feeling my way to the kitchen after sundown. Some might see this contest as a bit too fervent, but I found something refreshing in the darkness -- a conscience free of guilt.

Normally, my day is rife with guilt because I call myself an environmentalist. I'm not chaining myself to trees, but I'm green enough to understand my contribution to the daily depletion and degradation of our natural world.

It starts with the morning shower where freshwater pours down the drain - a precious resource steadily depleted. I do not run the water while brushing my teeth or shaving, but I still take a shower every day.

Around the corner is the local Johnny-on-the-Spot auto repairman operating on the street, cash only please. He pops open radiators and drains iridescent gunk into the storm drain. When it rains, the toxins will wash directly into the Hudson River. But I am quiet. What am I going to do, bark at a guy who simply does not know any better? Maybe I should. Maybe this is guilt by reticence.

Standing on the subway platform, a young man finishes his drink and throws his empty cup onto the tracks. I frown, but say nothing. The subway is already artificial and soiled, but that's not the point, trash goes into trash cans - that's civilization 101.

I am happy to be able to take a subway, and secretly relieved that the air-conditioning functions so well, even knowing full well the enormous amount of juice necessary to make me comfortable on my little commute.