At a recent party, residents of the Ditmas Park neighborhood in Brooklyn shared their strategies for walking home from the Cortelyou Road subway station after dark. Some simply get off at the next station on the line. Some take circuitous routes, going out of their way to avoid one block of Marlborough Road. And a teenage boy talks to his parents on his cell phone until he gets to another block, hoping to quickly alert them to any problem.

At a recent party, residents of the Ditmas Park neighborhood in Brooklyn shared their strategies for walking home from the Cortelyou Road subway station after dark. Some simply get off at the next station on the line. Some take circuitous routes, going out of their way to avoid one block of Marlborough Road. And a teenage boy talks to his parents on his cell phone until he gets to another block, hoping to quickly alert them to any problem.

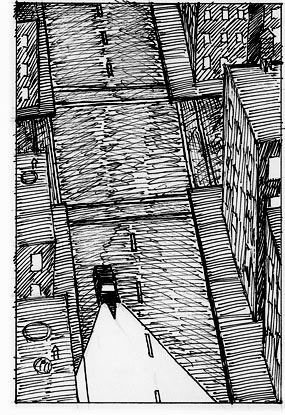

Marlborough Road between Cortelyou and Dorchester is not a hotbed of crime. But it is extremely dark.

The entire tree-lined block has only three street lights, compared to four on the next block. The block became more forbidding last year when a bar on the corner — whose feeble light spilled out a bit on the dim sidewalk — went out of business.

Most urban resident equate light streets with safer streets. Tourist guides and tips on how to live safely in the city advise people to avoid dark streets. Specific crimes, including the rape of the Central Park jogger, have been blamed on a lack of lighting.

Astronomers and sky gazing enthusiasts say that street lights make it difficult to see the night sky. They note that while in theory as many as 2,500 stars could be visible in a typical night sky, a person standing in midtown Manhattan is likely to see no more than 15. And lights can glare into apartments and homes, keeping people awake.

But the barriers to adequate lighting in New York are less likely to be concerns about light pollution than issues of cost, wiring and maintenance.

The Department of Transportation is responsible for installing and maintaining 325,000 New York City street lights. Its electric bill alone for the lights totals $50 million a year, according to department spokesperson Lisi de Bourbon.

The 311 city hot line handles complaints about broken street lights. A person can also file an on-line complaint form. The form lists more than 30 things that can go wrong with a street light from being burnt out to having exposed electric wires, shining in the wrong direction, or missing the door at the lamp post base.

People filing a complaint receive a work order number that enables them to check on the status of the job in the days ahead. The department says that its streetlight maintenance contractors must respond within 10 days of being notified of a problem. That does not mean, though, that the contractors have to repair the problem within that time. Instead, they can, for example, note that the job calls for a major repair — such reconstructions of the lamppost's concrete foundation — or refer the problem to Con Edison.

Complaints do get results. According to a recent article in the Bronx community newspaper the Norwood News students in a local middle school action club noticed that a number of street lights were out in the Williamsbridge Oval. "The lights are important because it keeps bad people out of the park," club member Chris Rambarran told the paper.

And so the club began a telephone campaign to get them fixed. It took eight rounds of calls to the transportation department but, the lights went back on and the club received a letter from the transportation department, lauding the role it played.

Getting a street light installed involves a different procedure. The transportation department web site provides no form for this and an operator at 311 had to look into the issue before advising a caller to send a letter to transportation commissioner Iris Weinshall.

But Terry Rodie, of Community Board 13 in Brooklyn, which includes the Cortelyou Road subway station, says improving lighting can be "an easy thing to take care of." Once the request is made to the transportation department, it brings in equipment to measure the light on the street in question and determine whether it is sufficient. Although Rodie said she was not familiar with the Marlborough Road block, she said foliage on trees can make a block seem darker. And she said light from any commercial establishment on the block is also taking account.

In deciding whether to grant the request, says de Bourbon, the department follows guidelines set out by the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America. "It's really more scientific than you think," she says.

The "real hang up" in improving lighting, says Rodie, is not the city but Con Ed. "They have a backlog with this kind of thing."

(Do you have dark streets or broken street lights in your neighborhood? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Gail Robinson

|