Related Articles: My Own Private Blackout Mike Misner explains why it was in some ways a good thing -- blackouts make environmentalists such as himself feel less guilty. Sep 15, 2003. After The Blackout -- Going Back To The Experts New Yorkers were among the victims of the largest blackout in the nation's history - and it had nothing to do with the research Con Edison was conducting. Aug 18, 2003. Studying How to Avoid Blackouts Con Edison has opened a new research lab -- a mock manhole in the Bronx -- to study the problem. But critics say it could do more. Originally published just three days before the Blackout of 2003 -- Aug 11, 2003. Related Links: • Blackout 2003 - Gotham Gazette's Coverage • Blackout Message Board |

Our system of electricity, begun a century ago, consists of large centralized power plants and a complex network of cables and wires called a transmission "grid" to bring the power to customers. A huge number of components in the system interact with each other, sometimes in ways that engineers do not anticipate.

In any system of such size and complexity, failures are likely to occur, as Charles Perrow pointed out in his 1984 classic, Normal Accidents: Living With High-Risk Technologies, in which he explained why failures are common in such systems as the chemical and nuclear power industries.

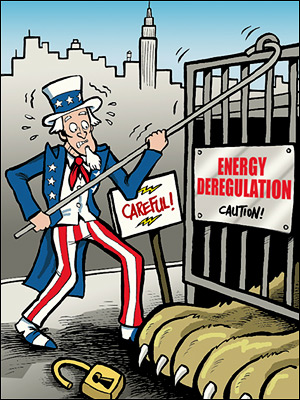

But it is not just a question of size. Ironically, part of the problem rests with the very laws set up over the last couple of decades to improve the delivery of electricity.

POWER TO PEOPLE

In 1882, Thomas Edison built the world's first electrical generating plant on Pearl Street in New York City's financial district. The plant powered the electric lights in local businesses. The era of electric distribution followed shortly after. In 1896 electricity created by water turbines at Niagara Falls was transmitted 20 miles away to the city of Buffalo where it powered lights and trolleys.

For nearly a century, most electric power has been created by large power plants built near cities where demand is the highest, and then distributed through the grid system of transmission lines, which connects power plants together and connects plants to buildings and homes.

Historically, monopoly utilities built these transmission lines to connect one power company to another. The lines also provided emergency power if a neighboring area lost power from one of its generators.

The system was supported and promoted by a web of federal and state government regulations, which determined how energy could be created, where it could be distributed, and at what rates it could be sold. These laws were created not only to protect consumers, but also to ensure that utility companies made enough money and attracted enough investors in order to provide electricity to consumers.

As energy prices rose in the 1970's and 1980's, policy makers began to believe that electric utilities -- like the airlines, telecommunications, and trucking industries, which were also governed by federal and state regulations -- could produce better products at cheaper prices if the system were regulated less, allowing it to operate under free-market principles and new technologies.

In 1992, President George Bush signed a new energy policy into law. Independent companies could now sell power to distant cities and use transmission lines of several utility companies to deliver the power.

As deregulation gained momentum, the relationships between former monopoly utilities became strained as they started competing against each other. Some power generators now try to sell power to far away states where they can get the highest prices.

CALIFORNIA'S LEGACY

In 1996, California became the first major state to revise its regulation of electric power to permit consumers to choose their own electricity provider.

The promise of competition stemmed in part from the disparate prices paid by customers across the nation. Under regulatory practices, state commissions approved the rates paid by customers based on the value of the equipment used to generate, transmit, and distribute electricity along with the cost of other expenses such as fuel. In some parts of the country, particularly California and New England, rates were high because of the high cost of power plant construction and fuel.

In 1996, the California legislature passed a bill that would allow retail customers to choose their energy supplier by January of 1998. More than 200 companies registered to resell wholesale electricity to residential and business consumers, and residential customers saw an immediate 10 percent reduction in rates.

Due to a number of factors, including power companies looking to sell their power elsewhere, a drought in the Northwest, rising natural gas prices, and the lack of long term contracts, wholesale prices rose more than five times the previous amount by May of 2000

As a result, the California Independent System Operator imposed price caps, meaning that the generators of power could not ask for prices above a certain level. Upset at the caps, power generating companies often sold power out of the state, thus reducing supply for customers in the state. Some companies found themselves unable to compete and went bankrupt.

Consumers also suffered. Because of inadequate power supplies, "rolling blackouts" of 60 to 90 minutes became necessary so electricity could be rationed around the state. In the first six months of 2001, California experienced rolling blackouts 38 times.

After the events in California, lawmakers became wary about how to proceed. Some states have moved toward more regulations, others have moved toward less.

The electric utility industry still remains in flux. This uncertainty puts investors and utility managers in a bad position, since they do not know what is going to happen in the future. Independent generating companies also hesitate to act because they do not know if they will be operating in a competitive market, a more regulated environment, or some mixture of the two.

THE 2003 BLACKOUT

While the details of the recent power failure that shut down more than 100 power plants in New York, Ohio, Michigan and Canada are still being investigated, it is clear that the current confusion over how the nation's energy industry should or should not be regulated played a key role in the largest blackout in the nation's history.

Investigators say there was a failure in the transmission system. And, thanks to deregulation, there is growing concern and confusion over how these systems should be monitored and who should pay for them.

In some states, the transmission system is run by the state agency, an Independent System Operator. While the utilities companies own the lines themselves, they do not have control over them and are not eager to invest billions of dollars into them.

In other states, the companies own the transmission lines, but the rates remain regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, so that they cannot make as much as they could if they built new power plants and could sell the power at market rates.

Before deregulation, the North American Electric Reliability Council established voluntary rules to deal with problems with the grid, helping to ensure that a problem did not cascade through the entire system. With the recent blackout, many have speculated that some utilities may not have been following these voluntary guidelines due to competitive pressure.

PREVENTING FUTURE BLACKOUTS

I hope that the current investigations into the 2003 blackout will lead to broad solutions beyond simply beefing up the existing system and building more power lines.

We are not going to get rid of the big power plants and transmission lines that we now have, but to minimize the possibility of widespread blackouts in the future, the country may need to retreat from the traditional paradigm of the electric utility system.

Between 1907 and 1980s, the paradigm consisted of regulated, regional utility companies systems that built large, centralized power stations and transmitted electricity through power lines to customers. We still live with a system built when these types of centralized power plants made sense.

But it may make more sense now to begin moving (at least partially) toward a decentralized system that contains small scale, modular and diverse types of equipment that produce power close to cities or even within buildings that use a lot of electricity.

Employing diesel generators, or better yet - from an environmental point of view - fuel cells, micro turbines, wind turbines, and photovoltaic cells, such a system would reduce the strain on the existing grid by providing power to users without depending on transmission lines at all.

It would also allow big uses of power to continue operating if parts of the grid failed, due to problems on the grid or to a terrorist attack.

Finally, it would give the decentralized producers of power an opportunity to sell surplus power to other customers through a local distribution network.

While technical challenges remain for implementing such a distributed system, it may provide at least part of the solution for dealing with a utility system that appears to be reaching technical and managerial limits.

Richard F. Hirsh is a professor of history of technology and science and technology studies at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia. He authored a series of essays for the Smithsonian Institution's website on the history of deregulation and the book Power Loss: The Origins of Deregulation and Restructuring in the American Electric Utility System.

Related Articles

My Own Private Blackout

Mike Misner explains why it was in some ways a good thing -- blackouts make environmentalists such as himself feel less guilty. Sep 15, 2003.

After The Blackout -- Going Back To The Experts

New Yorkers were among the victims of the largest blackout in the nation's history - and it had nothing to do with the research Con Edison was conducting. Aug 18, 2003.

Studying How to Avoid Blackouts

Con Edison has opened a new research lab -- a mock manhole in the Bronx -- to study the problem. But critics say it could do more. Originally published just three days before the Blackout of 2003 -- Aug 11, 2003.

Related Links

• Blackout 2003 - Gotham Gazette's Coverage

• Blackout Message Board