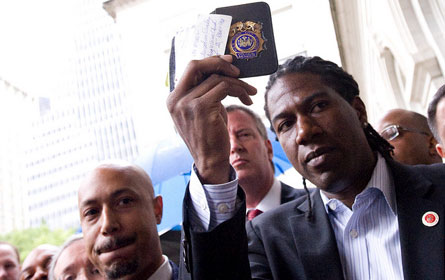

Williams Proposes New Stop and Frisk Controls

Councilman Jumaane Williams introduced a new bill last week, designed to increase police accountability and limit racial profiling, especially as related to the Stop and Frisk program, where police halt and pat people down for weapons. The bill drew both support and criticism from groups both for and opposed to current New York City Police Department policies.

The bill forbids using race, gender, ethnicity, sexual identity and other characteristics as a reason to stop somebody on the street. It creates the equivalent of Miranda rights for searches, where officers would have to inform people they stopped that they need not consent to a search. Finally, officers who are not on undercover assignments must hand out personal business cards to people they stopped.

“It’s not going to solve all the problems but we think it will make a dent. We are for better policing and safer streets,” said Williams at a conference outside City Hall as February rain fell on the spectators. “You see people here in the rain and the cold saying â€please stop this.’”

The NYPD did not return phone calls requesting comment on this subject.

The Numbers and Motives

Police stopped a record 684,330 people in the city last year, a steady yearly increase from 398,191 in 2005, according to NYPD data. Black and Hispanic people comprised 87 percent of those stopped, with black men being the most frequently stopped group. Whites comprised only 9 percent of the total. Most of the stops occurred in minority, high-crime neighborhoods such as East New York.

According to the NYPD patrol guide, a stop and frisk procedure is designed “to conduct criminal investigations and protect uniformed members of the service from injury while conducting investigations involving stop and question situations.” The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1968 that police can stop people without probable cause, on a lesser basis of “reasonable suspicion.”

Standards of reasonable suspicion are vague and give officers broad discretion. Police can stop someone who looks like a known criminal or is walking in a way that suggests a concealed weapon. Additional considerations can be made for time of day and whether an area has a high crime rate. Since 2003, all NYPD officers must fill out a special form for each stop. The form, called a UF-250, comes with a checklist of reasons for the stop. Critics of the NYPD say that the police rarely fill out all of the forms and most stops go unreported.

In 2011, 12 percent of people stopped were arrested, which is down from 14 percent in 2010 but fairly consistent with the years before that, when the stop and frisk arrest rate hovered around 10 percent.

Even though stops and frisks are designed to catch criminals and illegal weapons, police often don’t use them that way. Reasons such as “suspicious bulge,” “actions indicative of a drug transaction” and “actions indicative of a violent crime” were listed less than 10 percent of the time in the first half of 2009.

On the other hand, police listed “furtive movements” as a reason in almost half of all stops they made in the first half of 2009. Other major reasons for stop included “casing victim or location” and “other.” The data came from the activist organization Center for Constitutional Rights which monitors NYPD reports.

The rising stops are an extension of Commissioner Kelly’s statistics-oriented approach to law enforcement. The focus on numbers started under the Giuliani administration. Kelly defended the practice as essential to law enforcement and said that it’s perfectly normal to stop this many people in a city of 8 million residents.

“This is a proven law enforcement tactic to fight and deter crime, one that is authorized by criminal procedure law,” Kelly told the Associated Press.

Congressman Peter King, who chairs the Homeland Security committee, spoke at a press conference of Muslims who support the NYPD on Monday. Among his other comments, he praised the stop and frisk policy, saying that it prevents murders and he sees no violation.

Police Spokesman Paul Browne said of last year’s stop and frisk report: "That is a remarkable achievement—5,628 lives saved—attributable to proactive policing strategies that included stops," Mr. Browne said.

Dissension

Many of Kelly’s opponents disagree, saying that his policies don’t have a direct impact on crime and force some of New Yorkers to live in more fear than others. The most recent chorus of complaints came from Muslim communities, following AP and NY Times reports that the NYPD has been spying on Muslims and showing a controversial film about radical Islam in police training.

“One time, three undercover cops pulled guns on me. One to my neck, one to my temple and one in my chest and they told me that if I moved, I’d be shot,” said Steve Kohut, with the activist group Communities United for Police Reform. “This has been ongoing for a long time.”

Some former police officers say that the stops have a lot to do with pre-emptive policing and focusing on numbers, rather than building relationships with communities and that excessive stop and frisk hurts law enforcement by undermining community trust in the police.

“The NYPD has lots of premonitions about black males: â€ultimately they'll commit crime, let's automate it, all we have to do is press a button.’ They want to get as many black and Latino youths in the system as possible,” said Noel Leader, a retired detective and co-founder of 100 Blacks In Law Enforcement.

He added that most police officers don’t like doing stops but if they fail to get a certain number of stops per month, they might make their commander look bad in front of his superiors and get punished with bad assignments and reduced vacation time. “At the end of the day, the department takes on the personality of Commissioner Kelly,” said Leader.

NYCLU Director Donna Lieberman said that the NYPD’s current policies subject “hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers to stop and frisk for walking while black “ and “walking while Latino.” She went on to say that Williams’ bills are a “win-win” for New Yorkers. “It’s a big deal,” she said.

Council members Yvette Clarke, Margaret Chin, Julissa Ferreras, Ydanis Rodriquez, Stephen Levin, State Senator Eric Adams and Assembly Member Karim Camara endorsed the bill.

Not everyone agrees that the bill is a big deal. Leader called it “Another ineffective, nonsensical bill to prevent abuses by NYPD.” Leader complained that the bill would create more rules which are unlikely to see enforcement and that council members need to shift their efforts towards making sure the commissioner obeys existing rules, by going to the governor or higher if necessary.

“Politicians will write all the laws they want but com Kelly will show that they don't have respect for these laws,” said Leader. “Officers who break the law have to be punished. If officers do illegal stops should be suspended or terminated.”

Councilman Williams is the chair of the Oversight and Investigation Committee of the City Council and co-chair of the task force to combat gun violence. He has butted heads with the NYPD over its policies in the past and was once arrested after attending the West Indian Day Parade.

Controversial Video Sparks Outrage at NYPD

Muslim organizations last week called for the resignation of Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly and NYPD spokesman Paul Browne, the creation of a police oversight body and the retraining of 1,500 officers.

Many Muslims reacted with worry and outrage to news reports that Kelly voluntarily participated in an interview for The Third Jihad, a documentary film that purports to show the dangers of radical Islam. The film, which many Muslims called propaganda, was screened on constant loop during police training, where about 1,500 officers saw it at least once.

The news contradicted the police department’s earlier statements and letters sent to Muslim activists, in which he said that he had nothing to do with the film and that his comments were used out of context. Police spokesman Paul Browne was caught in a lie, telling the New York Times that the producers of the film never interviewed the Commissioner, shortly before a producer emailed the Times with the date and time of Kelly’s interview.

“Muslims know that there are 1,500 police officers that have this poison in their minds now. How do you think someone will feel walking down the street, looking at a police officer, thinking â€wow, I wonder if he saw that video’?” Said Linda Sarsour, a spokeswoman for the Muslim American Civil Liberties Coalition, a group of 15 Muslim organizations throughout New York.

The video raised concerns about NYPD's surveillance programs, which targeted Muslim communities. The coalition suspected surveillance for a year and a half but only saw proof following an a href="http://www.ap.org/pages/about/whatsnew/wn_082511a.html">Associated Press report which exposed the programs, which stemmed in part from a CIA operative’s partnership with the police.

Apologies

Commissioner Kelly apologized on Friday, saying “I offer my apologies to members of the Muslim community, in particular, who would find the film inflammatory and its airing on Department property, though unauthorized, to be inappropriate.”

Mayor Michael Bloomberg also defended Kelly and Browne at a Thursday news conference. “Ray proudly visits more mosques than many people whose faith is practiced there,” said the mayor, adding that Kelly should not step down and he will not create any oversight body for the NYPD and that Browne was acting in good faith.

But the coalition rejected both the mayor’s statement and the commissioner’s apology as “condescending” and said they would continue trying to put pressure on city government to get their demands passed.

Speaking Out

Cyrus McGoldrick, the civil rights manager of the New York chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) said “The concern is that he knowingly took part in a propaganda film and also the fact that he's a police commissioner of the largest police force in the world. He's listed as commissioner, not just a private citizen [in the film credits], representing NYC and our tax dollars, legitimizing a propaganda film.”

Councilman Jumaane Williams said “Mayor Bloomberg and I agree that screening an Islamophobic film to NYPD officers, particularly during antiterrorism training, was unacceptable. It would stand to reason that if he understands this, he should also understand that this is a product of this city's unjust policing culture that excuses this kind of behavior.”

Other council members who came out against Kelly’s actions include Letitia James of district 35, Vincent Gentile of district 43, Ydanis Rodriquez of district 10, Daniel Dromm of district 25 and Brad Lander of district 39.

"The Third Jihad"

The Third Jihad was produced by members of the Clarion Fund, a conservative non-profit in New York, which also made Obsession: Radical Islam’s War Against The West, another controversial film. At one point, The Third Jihad’s narrator says: “Americans are being told that most of the mainstream Muslim groups are moderate when in fact if you look a little closer you'll see a very different reality. One of their primary tactics is deception."

Clarion Fund interviewed former Secretary of Homeland Security Tom Ridge, former mayor Rudolph Giuliani and other government officials, journalists and think tank employees, some of whom are Muslim. In the film, Commissioner Kelly talks about nuclear security in New York for a little over a minute but his original interview with the producers lasted about 90 minutes.

Raphael Shore, The Third Jihad’s producer, defended the film, writing that he regrets that the film was taken out of counter-terrorism progam of the NYPD and that his “high-quality and impactful documentaries touch some very sensitive nerves.”

An Issue of Trust

Muslim activists first became aware of the film’s screening in of police training centers when a Muslim recruit brought it to CAIR’s attention in 2010. The Village Voice later put out a story in January 2011, revealing that the video played as part of the NYPD’s counter-terrorism training.

Browne issued a statement that the video played “a few times” while recruits were filling out paperwork. In reality, the video played on continuous loop between three months and one year of training. Documents received by the NY Times show that someone from the Department of Homeland Security supplied the video even though the department hadn’t authorized it.

“What else are they lying about? I'd be worried as a New Yorker,” said Sarsour.

The NYPD is still dealing with fallout from August’s Associated Press report that the NYPD had an extensive spying program set up in Muslim communities in New York City after 9/11. The architect of this program was Larry Sanchez, a former CIA agent, who worked for the agency until 2004 and was on NYPD payroll from 2007 to 2010. The CIA’s inspector general found that Sanchez operated without sufficient supervision. The agency’s top lawyer never approved sending an agent to New York. Commissioner Kelly defended the partnership.

Kelly’s opponents say that the commissioner never made time to address their concerns and only deals with handpicked Muslim leaders to make himself look better. They called for a stronger oversight body to be able to audit the NYPD, saying that the Civilian Complaint Review board is designed to focus on individual complaints instead of investigating systemic flaws in the department.

They also called for the full retraining of 1500 police officers, from rookies to lieutenants, out of concerns for the safety of Muslim New Yorkers.

“At the very least, we want that,” said McGoldrick.

Community Members Struggle With Stop and Frisk

Within half a year, Harlem mother Mary Black went from not even knowing what a â€stop-and-frisk’ was to headlining protests against it. She quickly learned that in her neighborhood, snitching on police cleared a crowded room, fast.

Beginning last June, police stopped Black’s 16-year-old son three times in six months. The stops resulted in disorderly conduct summonses, all of which the court dismissed. But the pattern worried Black. Double-checking the whereabouts of her youngest child, knowing the parents of his friends—these methods helped her to successfully raise her first two. But these stop-and frisk-incidents added an unexpected chapter to her already dog-eared parenting handbook. They required interactions with the criminal justice system that Black had not anticipated. Her son did not have a record but each stop increased her fear that soon, he would.

Then in December, during a fourth stop, police arrested Black’s son outside their apartment building on 137th street. Alerted by a neighbor who rang her buzzer, Black flew down four flights of stairs in a house robe, socks and not much else. After tears and pleas, Black says she left the precinct that night with her son, another pink summons for disorderly conduct and a determination to defend not just her son but everyone else’s too.

For her first rally, planned with the Stop Stop and Frisk Campaign, Black says she distributed over 750 flyers throughout her neighborhood expecting about 100 to attend and share their own stop-and-frisk stories. Fifteen people came.

“That’s the saddest part,” Black says. “Everybody knows stop-and-frisk is an injustice but it’s like you’re fighting by yourself.”

Black is learning first-hand the challenge facing the city’s revitalized but fragmented police reform movement as it looks to influence the 2013 elections: mobilizing ordinary New Yorkers to speak out against the NYPD’s controversial stop-and-frisk practice.

Just the Facts

Actually, nine out of every 10 stops are innocent. Of the 3 million stops conducted between 2004 and 2009, about 4,200 yielded guns, or, a seizure rate of 1.5 guns for every 1,000 stops, according to Columbia University professor Jeffrey Fagan. The NYPD hasn’t yet released last year’s tally but 2010 saw more than 600,000 reported stops, a 500 percent increase since 2002, the year that the mandatory reporting law from a compromise deal between former mayor Rudy Giuliani and city council took effect.

And even though the vast majority of innocent stops occur in black and Latino neighborhoods, interviews reveal a reticence on the part of ordinary New Yorkers to publicly speak out against the practice that NYPD has long credited with getting guns off the street and helping to reduce crime. Their reasons run the gamut from agreeing to fear of retaliation from local police. All point, however, to the corrosive effect of a citywide culture that allows for only two positions, pro- or anti-police, and no middle ground.

Looking for Middle Ground

At a recent Saturday afternoon rally to address, according to the event’s flyer, “gun running; planting drugs; stop, question and frisk; and racist Facebook posts,”--all recent incidents involving officers as perpetrators--lead organizer and council member Jumaane Williams began with an apparently necessary preface:

“This is not an anti-NYPD rally. This is a pro-better policing and safer streets rally,” said Williams to the roughly 80-person, multi-generational crowd that had gathered under the arch at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn. Many were community activists from throughout the city but also because of location, on-lookers included runners and shoppers at the weekly farmer’s market.

“We can have those conversations,”--Williams had just led the crowd in a round of applause and praise for NYPD, including officers on scene--“and still want our police officers to be accountable.”

Disclaimers denote however that the forthcoming statement will not be the status quo.

“The police has been very successful at painting critics as either pro- or anti-police,” says Alex Vitale, associate professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and expert in community policing.

“There’s no room for positive constructive criticism so that even those politicians who speak out, feel the need to do a ton of handholding and reassuring--and this [from] an African-American man who’s been subjected personally to these policies.”

The Stigma

In a climate that pressures Williams, an elected official with no history of militancy, to sugar coat criticism of NYPD, staying silent on stop-and-frisk is not an unreasonable option for everyday black and Latino New Yorkers. Unlike Williams’ West Indian Day Parade incident, their police encounters will not be filmed or shown on the evening news.

“They’re afraid,” says Black, explaining why private support from friends and neighbors does not translate into bodies on the street. Her own family worries that because of her newfound activism police may target her son.

Lumumba Bandele is a senior organizer with the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund and member of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement he has participated in anti-police brutality campaigns since the mid-1990s.

Bandele frames residents’ decisions about whether to address stop-and-frisk abuses in their neighborhoods as a choice between the lesser of two evils: “Do I want to be attacked by the police or by my people? Who will do me the least harm?”

Foot traffic, he says, bears towards the latter direction.

Community Needs

But while some community members stay silent out of a fear of police, others stay silent out of a fear of criminals. Stop-and-frisk, they say, helps to keep them safe.

“We assumed that white people on the other side of town had been calling for larger police presence when in truth it has been our grandmothers,” says Bandele, whose coming of age in Bedford-Stuyvesant included so many stops he says he lost count.

Repeating Bandele’s experience as a younger man on another generation is, for some New Yorkers living in high-crime areas, an acceptable casualty in the war against drugs and violence.

“Most of the more established members of these communities, like homeowners, religious leaders and community board members,” Vitale says, “are often more concerned about crime than civil liberties violations.”

Looking For Middle Ground

However, some local leaders are reassessing the cost of silence. Brooklyn’s Community Board 17 co-sponsored Williams’ police accountability rally. Manhattan’s Community Board 10 recently voted 25-7 in favor of a resolution initiated by the borough president, calling on NYPD to reform stop-and-frisk.

“A lot more parents and seniors are approaching me for help getting their son or grandson out of the grip of police,” says Andre Mitchell, founder and chief executive officer of Man Up, Inc!, a multi-service community center in East New York.

“They asked for more police but not with the understanding that stop-and-frisk would target any and everybody.”

Mitchell works both sides. He partners with police to help curb gang violence and runs workshops for youth seeking ways to handle being stopped by them. A frequent mediator, he blames stop-and-frisk for aggravating his efforts.

“I try to close the divisions but it doesn’t help when police stop people for no reason at all,” he says--like, loitering, crossing the park after dusk, sitting in the park, riding a bike on the sidewalk. Then again, he adds, even officers who admit to him that they disagree with the policy must follow their orders.

“Change is going to have to start at the top,” Mitchell says, “with the mayor.”

Reached for comment on whether, as councilman Williams’ charges, stop-and-frisk is a problem, the mayor’s press office referred the matter to NYPD.

Inside Manhattan Criminal Court last Tuesday, Mary Black finally exhaled. The arraignment judge hearing evidence in her son’s disorderly conduct case indicated that telling a police officer, “I don’t give a fuck,” is insufficient justification for an arrest. A trial has been set for March.

“I feel a lot better,” Black says.