The Price of Increased Surveillance

There are 82 police cameras and others cameras from stores trained on the streets in and around Times Square -- not to mention thousands in the hands of tourists -- but none of them seems to have picked up an image of Faisal Shahzad who is in custody for trying to set off a big homemade car bomb at the height of the theater rush May 1. The video most circulated by police of a suspect showed a white man changing his shirt on the sidewalk near the SUV packed with explosives. Lucky for him, a mob didn't find him and tear him limb from limb.

The bombing was averted that night due to conscientious community-minded vendors who contacted police as they often do when they spot something suspicious -- especially difficult in a district full of eccentricity. Shahzad was apprehended through good, old-fashioned police work -- tracking this bumbling would-be terrorist through identifiers on the vehicle that he had recently purchased.

Nevertheless, the early response of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, police and at least one editorial board to this incident was to call for more high-tech security. While most public officials seem to support that idea, a few critics have questioned the efficacy of such a system and the effects it would have on privacy and on our basic civil liberties.

Expanding the 'Ring'

New York is already in the process of blanketing the financial district with a "ring of steel" surveillance system modeled on London's. Now it wants to extend that to Times Square.

The system includes "cameras, sensors and analytical software," AFP reported, that, according to Police Commissioner Ray Kelly would trigger alarms when it "noticed an unattended bag or car circling a block too many times to be considered normal."

"Every public nook and cranny of midtown Manhattan should be covered by an integrated network of supersharp digital cameras that are monitored in real time,” the Daily News wrote in an editorial. "The only obstacle is money -- which actually should be no object given that lives are at stake." It will cost an estimated $110 million to expand the downtown system into Times Square.

Security vs. Freedom

Public officials are not oblivious to the concern about civil liberties. Speaking at a joint press conference in London with Mayor Boris Johnson shortly after the Times Square incident, Bloomberg said expanded surveillance "is controversial, but we have to make a balance between civil liberties and protection. We live in a very dangerous world."

Johnson, whose Underground system alone has 12,000 closed circuit TV cameras (to New York's 4,300, only half of which work), said, "Of course everybody understands the civil liberties arguments and the concerns, and they're very, very strong in this city and country, just as they are in New York."

Civil libertarian Bill Dobbs worries that the cameras are another sign that we are slowly giving up our basic rights. "All searching people does is get people used to the idea of being stopped and searched. We're getting to the point where when someone resists this, the public will wonder what they're hiding," he said.

Dobbs added, "Now, everything and everybody is under suspicion; some simply because of their race or religion suffer even more police and public scrutiny. ... We are continually pushed to give up cherished freedoms to fight an unseen enemy."

Sahid Buttar, executive director of the Bill of Rights Defense Committee, raised similar issues. "While surveillance is in some ways the antithesis of profiling (surveillance is broad and limitless, whereas profiling seems focused and targeted), both government practices offend the same constitutional principle of individualized suspicion inherent in the First and Fourth Amendments," he wrote.

Do They Work?

Dobbs also questions the effectiveness of the plan. "The [Metropolitan Transportation Authority] put up cameras in the 1980s but gave up on them because they couldn’t monitor them," he said. "Technology provides false hope."

In light of the various concerns, the expansion of the ring of steel needs more discussion and review, said Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

"National security and warding off terrorism are enormously vital jobs and we all hope the police department is doing it well -- fantastically, in fact. To do it right, we have to not simply accept at face value every proposal put forward because it ought to work. The City Council and the mayor have to use the same high standards they put on other areas of government on the police department and its security effort," she said.

While she acknowledges "cameras can be helpful," she said New Yorkers need to "demand more than just assertions that they will do the job," particularly in the current economic climate.

The proliferation of cameras and images is “creating a big haystack of information and we're looking for needles," Lieberman said. "We need to be strategic in our surveillance."

And she noted that, in the case of the attempted bombing in Times Square "it was the alertness and civic mindedness of ordinary people and police" that led to a resolution of the incident.

Fate of the Footage

So far, the administration has not said what it will do with the information and images it collects with its surveillance cameras. This bothers Lieberman.

She believes adequate safeguards do not currently exist to protect people against the improper use of their images. And she said that the "potential for abuse is more than imagined," starting with the potential for identity theft if the information is compromised.

Example of possible abuses abound. CBS News recently did an expose on how photocopy machines memory cards store tens of thousands of images of documents that are not wiped clean when the machine is sold secondhand. One of the machines in CBS's investigation had police records from Buffalo, another medical records from a hospital.

In an example closer to home, Kelly has said the police department plans to createthe city police maintain a searchable database of the hundreds of thousands of innocent New Yorkers -- mostly African American and Latino young men -- who are stopped and frisked every year. City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Councilmember Peter Vallone, Jr., chair of the Public Safety Committee have written to Kelly expressing concern that such a retention of records would violate the spirit of the law mandating that criminal records be sealed. Quinn told me on May 17 that the council and police department staffs were in the process of setting up meetings about the matter.

The civil liberties union filed a class action lawsuit on May 19 to stop the police from keeping this database of innocent people. The police department has stopped and frisked 3 million people since 2004 and 575,000 just last year, a record. About 80 percent were African American and Latino.

Two of the plaintiffs tell their stories in a short film. Clive Lino, 30, an African American Harlem resident who works with special needs kids, was stopped "at least 13 times by NYPD officers between February 2008 and August 2009," but never was guilty of anything, the NYCLU said in a release. "They make me feel like a criminal or suspect when I haven’t done anything wrong," Lino said in the release.

"Innocent New Yorkers who are the victims of unjustified police stops should not suffer the further injustice of having their personal information shared indefinitely in a sprawling NYPD database” that may contain the names of more than 100,000 innocent New Yorkers, Lieberman said.

In general, Lieberman wants to require government to do "a privacy impact statement" when it seeks to expand surveillance. But trying to get information out of the government agencies that do this work -- from the New York Police Department to the FBI -- is "like trying to take blood from a stone," she said.

The police department did not respond to an e-mail request for comment on any of these issues. In the past, its spokespeople have deflected questions about security measures by citing security concerns. For this story, they would not answer questions about how many personnel will be needed to staff the expanded surveillance system, how long images will be kept, who will have access to them, and what evidence they have that these expensive methods are more effective than traditional police work.

Trusting the Police

Public officials I spoke with said they had few worries about the increased surveillance. Quinn said she was "confident" Kelly was conducting surveillance "in an appropriate way," despite her concerns about his retention of data on innocent people who have been stopped and frisked.

State Sen. Tom Duane said, "I'm 100 percent civil libertarian" and the trend to a surveillance society "makes me uncomfortable," but it "is important that we do everything we can to stay safer." While he said he did not oppose investing in reasonable security measures, he added, " People should also invest in groups like the NYCLU."

Gov. David Paterson, for one, does not think current efforts go far enough. "The cameras in use now don't emit strong enough images for identification," he told me, adding he wants a better system that can.

At the Crossroads of the World

Neither privacy concerns -- nor the attempted bombing that prompted the discussion -- seemed to be of much concern to the people filling Times Square on the beautiful Saturday evening of May 15. Two weeks after the failed bombing, Ann Marie Carter was sitting outside there with her two grandchildren, Nicole and Peter Godleski. She acknowledged being "a little leery" of visiting Times Square, "but I talked with my daughter who told me it would be covered more by cops. We feel safe."

Indeed, police and police cars were everywhere in Times Square that night, including many from the counterterrorism unit.

Many in Times Square wondered whether people on the streets might be more effective at finding problems than costly surveillance equipment.

"We spend all this money on anti-terrorism and it was a vet [one of the vendors] that saved the day," said Jason Esponiza, 19, of the Bronx.

Amadou Doye, who has been selling art in Times Square for 20 years, said he always watches out for suspicious things as do his fellow vendors who, he said, constitute a community.

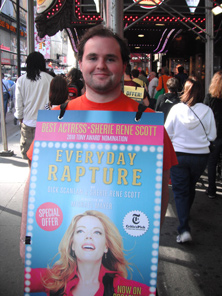

Vendors and people leafleting for shows and restaurants are a constant presence. Actor Ryan Cavanaugh, wearing a sandwich board for "Everyday Rapture," has been out there since winter. While he hasn't had to report anything to the police, he is more aware of the people selling illegal CDs on the street since an incident where one of them got involved in a gunfight some months ago.

But even those who question the cameras' effectiveness are not bothered by having them there. "I don't do anything that I'm ashamed of a camera seeing me do," Cavanaugh said.

"Certain things are necessary," Esponiza said, though he said this kind of surveillance might bother him more if it were taking place in his neighborhood.

Doye doesn't care how long the police hold on to the images they get . "If it is only for safety, they can keep them forever," he said.

Jason Faust, who leaflets for the long-running "Naked Boys Singing," said he was there the night of May 1. He saw the crowd gathering around the SUV and "didn't think much about it -- it's New York!" When the "pops" were heard coming from the vehicle, "the crowd started running, but I'm a New Yorker. I stopped."

He said that surveillance "has been around for years" and doesn't feel in infringes on his rights. While the cops were being a lot more watchful on this night, prior to the incident "half the time they were taking pictures of tourists" for them.

I tried to see if it would bother people to have a stranger they could see take their picture. It didn't. In Times Square where almost every tourist has a camera and police camera keep almost constant watch, no one seems to notice yet another camera -- or care.

The people who feel they just barely dodged mass death in Times Square are not thinking much about infringements of their civil liberties, but by not drawing a bright line somewhere, they may be forgoing rights they will never get back.

Andy Humm, a former member of the City Commission on Human Rights, has been in charge of the civil rights topic page since its inception in 2001. He is co-host of the weekly "Gay USA" on Manhattan Neighborhood Network (34 on Time-Warner; 107 on RCN) on Thursdays at 11 PM.

Council Approves Business Bill of Rights

The City Council offered small businesses their own version of the first amendment yesterday by requiring every city inspector give shop owners a business bill of rights during city inspections.

The bill, approved unanimously by the council, is one part of Council Speaker Christine Quinn's agenda this year to snip away at red tape for the city's small businesses.

Bill of Rights

The (Intro 118) bill of rights will notify business owners of their right to consistent enforcement of agency rules and to appeal violations. It also will notify owners that inspectors must behave in a professional and courteous manner, be able to answer reasonable questions relating to the inspection and be knowledgeable on the city laws and regulations.

"By passing this legislation we will cut away at red tape that can often strangle small business in our city and will make the process of complying with city regulations more business and user friendly and much more accessible," said Quinn.

The city already has established a bill of rights for passengers of livery and yellow cabs. Council officials say putting a similar document in business owners' hands will assure they are protected from any unscrupulous city inspectors.

It may be no freedom of speech or religion, but the city's business leaders say the measure is a step in the right direction.

"It’s a great first step," said Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce President and Chief Executive Carl Hum. "Business owners are going to realize, 'I can contest this bill [from the city] and I can contest this violation, or I have the right to actually complain about an inspector.' It is a very empowering initiative."

Toxic Parks

After the parks department installed crumb rubber turf in an East Harlem park, leading to elevated lead levels, council officials said it was time to monitor what went into city playgrounds and fields.

So the council approved legislation (Intro 123) Wednesday to establish an advisory panel that will examine materials used in city parks and playgrounds. The panel will not have veto power over what materials the Department of Parks and Recreation can actually use, but will provide the agency with recommendations.

The eight-member panel, half appointed by the mayor and half from the speaker, will report to the department every six months. No new material can be installed without a review from the panel.

Saving a Church?

The council also voted to give landmark status to the West Park Presbyterian Church on the Upper West Side. The status was approved by a vote of 47 to 2, with council members Vincent Ignizio and Peter Koo voting no.

Leaders of the church, which is 116 years old and is an example of Romanesque Revival architecture, opposed the status, and had wanted to tear down part of the structure for development.

Ignizio said the city should defer to the property owner during landmarking disputes.

Affordable Housing Revision

The council unanimously approved a small revision (Intro 66) to its 421-a affordable housing program to allow developers to receive benefits faster.

Currently, a developer must file several different permits to prove construction has started and to trigger the receipt of tax exemptions. The revision would no longer force developers to show plumbing permits, which they argue are issued later in construction. The revision will affect projects as far back as January 2008.

Disabled Fear Cuts to Van Service Will Force Them to Stay Home

After work, Milagros Franco wheels home in her motorized chair across the 2½-mile pedestrian walkway of the Brooklyn Bridge and then waits for a bus to her Manhattan apartment. "It saves time," Franco said. But she depends on an Access-A-Ridevan to get to work every morning, again, because that too saves time.

Now, though Franco worries that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's proposed cuts to Access-A-Ride could triple the time it takes her to commute to her job at the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled.

Access-A-Ride, the New York City Transit's service for people whose disabilities prevent them from using regular mass transit, now carries vans full of passengers door to door. Everyone is picked up at their home or office and then taken to their individual destinations. Under the service changes prepared by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, some passengers, instead of being taken directly to their destination, would be driven by the van to a bus, subway station or to another Access-A-Ride van.

The MTA also proposes to make access to Access-A-Ride dependent on weather conditions, so that service would change day-to-day and has proposed a number of other changes.

Spokespeople from disability groups charge that the cuts would add hours to a client's commute, making Access-A-Ride almost worthless. They say a trip that would take 15 minutes by a bus or subway now can last two hours on Access-A-Ride. The proposed service changes, they say, would add another two or three hours to the round trip, leaving many people with disabilities stuck in isolation in their homes.

The City Council will holding a public hearing on Access-A-Ride cuts on Tuesday at 1 p.m. at City Hall.

While some people with disabilities can and do use mass transit, approximately 20,000 people use Access-A-Ride every week. The program costs more than $451 million a year, and the MTA sees its proposed $40 million in cuts to Access-A -Ride as necessary to help alleviate the system-wide budget deficit of more than $750 million, according to Aaron Donovan, a spokesperson for the authority. The MTA has proposed an array of cuts including eliminating the free and reduced subway rides for students.

Metropolitan Transportation Authority chief Jay Walder has conceded that many of the reductions will be painful. "It's tearing my heart out right now," Walder said at a hearing earlier this month, "Last night at 1 o'clock in the morning I'm turning over in bed trying to figure out how to make the choices."

Longer Rides and Less Reliable Service

The MTA also has recommended applying more rigorous eligibility criteria for using Access-A-Ride, transferring more overnight service to taxis and other car services, making it more efficient and reducing personnel. The reduction in direct service, though, most alarms advocates.

Being driven to a bus or subway stop for part of the trip "would really discourage people with disabilities from going anywhere,” says Linda Ostreicher, director of public policy for the Center for the Independence of the Disabled, New York, a non-profit advocacy and support group. "Access-A-Ride is not able to keep a schedule, is not reliable now. Imagine waiting at home for an Access A Ride vehicle, getting dropped off at a bus stop, waiting for the bus, getting off the bus, and waiting for another Access-A Ride to get to your doctor's office on a day that you feel sick. Then imagine doing the whole thing again on the way home," Ostreicher said.

Evaluating every trip by weather conditions would be "time consuming and complicated," Ostreicher said. "It would require increased staffing, additional training and upgrading the current scheduling systems," and that, she believes, would wipe out any cost savings.

Advocates remain unclear how the transit authority would determine how weather conditions affect an individual's ability to travel on a given day. Many disabilities cause symptoms that vary from day to day, sometimes hour to hour. For example, some people with multiple sclerosis can experience heat intolerance that can cause decreased cognitive function, numbness, fatigue, blurred vision, tremor and weakness. For some people with cerebral palsy, cold can cause a tightening of extremities that makes it difficult to walk. Weather conditions like snow, ice and slush and rain create obvious problems for people in wheelchairs. Bad weather also makes it more difficult for people with low vision and blindness to navigate their path.

Franco said the cuts could affect her dramatically. Now, she takes a 7:45 a.m. Access-A-Ride van to her Brooklyn office, a 10 to 15 minute trip that gets her to her office one hour early.

The commute home is a completely different story. "Either Access-A-Ride doesn't show up, or they show up three hours later … or they may take a joy ride through the boroughs." Because the two wheelchair-accessible seats on the regular bus usually are already occupied by the time Franco would get on, she generally opts to wheel herself across the bridge.

"You gotta do what you gotta do to live," said Franco. She has had cerebral palsy since birth and has been wheeling across the bridge since attending Long Island University where she earned a bachelor's degree in social work.

On a bad weather day, though, she can't wheel. So she takes Access-A-Ride home on those days. "I can see that if I was subject to the service changes it would take so much time to get to and from work that I would not be able to keep my job. Both my clients and I would be stuck at home. I want to be an active participant in society. I want to help other disabled people," Franco said.

Fighting the Cuts

A numbers of local officials, including City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, council Transportation Committee chair James Vacca and other council members oppose many of the MTA's planned cuts. They say the reductions can be averted or reduced by reallocating federal stimulus funds and using capital money for operating costs.

"If these changes go into effect, the mass transit system would not be in compliance with the mandates of the Americans with Disabilities Act," Vacca said. The act makes it a violation of civil rights law for public transportation agencies, such as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, to discriminate against people with disabilities in providing service. As part of that, the agency must make good faith efforts to operate accessible buses, subways and trains and, in cases where that would result in an "undue burden" to provide paratransit, such as Access-a-Ride.

Obstacles in the System

New York's transit system presents a number of barriers to people with disabilities. While the bus system is 100 percent wheelchair accessible, riders say there are not enough buses to meet demand. And subway and taxi service are not accessible for the majority of New York's disabled.

Service changes could also strand clients with other physical disabilities, infirmities due to age, those with cognitive disabilities that make it difficult for them to remember bus routes and directions, some people with certain psychiatric disabilities, and some people who are hearing-impaired.

Only 70 of some 470 subways station are accessible, according to James Weisman, counsel to the United Spinal Association, a disability rights and veterans service organization.

The others pose various obstacles. Some feature a six to eight-inch gap between the platform and the train. "For people with physical disabilities and the blind, the fear of being dragged by the train is an anxiety that deters its use," Ostreicher said.

Elevators frequently do not work. And for some trips, elevators exist on the downtown trip but not the uptown trip or vice versa. A broken elevator can present a disabled person with a major problem. Weisman explains, "If a passenger arrives at a station where the elevator is out of service, they have to travel to the next accessible station in the direction they don't want to go, go back and re-board a train in the opposite direction and come out on the other side of their original station."

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority says that its 110 accessible subway and commuter rail stations have, among other features, elevators or ramps, large-print and tactile-Braille signs, audio visual information systems, telephones at an accessible height with volume control, and text telephones.

With all city buses accessible to wheelchair users, the buses provide 100,000 trips to wheelchair bound people a month, according to Weisman. On the other hand, with only 300 New York City taxis at least partially accessible to wheelchair users, it is "a happy coincidence if one … happens to be accessible when you hail it," Weisman said. "And it is impossible to tell which ones are accessible."

Cabs and Buses for All

Access-A-Ride costs the MTA $66 a trip. The rider pays $2.25 each way. In light of that, some advocates believe the transportation authority and the city government should look for less expensive alternatives that would still give people with disabilities the mobility they need.< For example, Weisman notes, if buses were not accessible, the additional Access-A-Ride van trips would cost the authority an additional $79 million a year.

More accessible taxicabs could also reduce Access-A-Ride trips. The spinal association supports MV-1, billed as the world’s first mobility vehicle. With production slated to begin in October, the taxi meets the guidelines of the Americans with Disabilities Act, without requiring conversions or retrofits. It can accommodate even power wheelchairs and scooters and up to five other adults. Power wheelchairs will board the taxi by driving up the ramp. Manual chairs will be pushed in by the driver. The wheelchair using passenger sits next to the driver in the front seat which is empty space where a wheel chair can be secured.' It would operate by both dispatch and flagging and would be accessible to everyone. They will begin to be manufactured.

If a sufficient number of MV-1 taxis roamed city streets, paratransit riders could get a debit or credit swipe-card and pay $2.25 for a cab ride with the Access-A-Ride system making up the difference. The MTA would still come out ahead.

"Even the longest taxi rides are less than half the cost of paratransit rides," Weisman said.

State Assemblymember Micah Z. Kellner, Assembly member, proposed the swipe-card system back in 2009. He estimated then that it could save taxpayers $50 million a year in paratransit services – $10 million more than the Metropolitan Transportation Authority Says it must cut from the Access-A –Ride budget.