Dog Runs

|

|

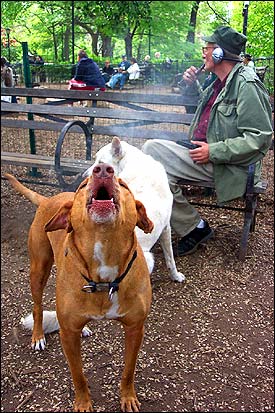

| Sounding off at First Run, New York City's first dog run. |

Mahatma Gandhi said that a society can be judged by the way it treats its animals. But in New York, another criterion may be how people treat each other when disputes over animals arise. The most contentious of such disputes center around dog runs:

• When the city first began constructing a playground on 42nd Street, a group of dog owners who opposed it sent a letter to the mayor calling the playground a "frivolous, costly, and ultimately wasteful construction."

• When dog owners at the Washington Square run became suspicious that a common water bowl may have spread a viral infection among dogs, they called in a veterinarian to examine the bowl. A pro-bowl contingent hired their own vet for a second opinion.

• At a community board meeting, a resident compared dogs in Stuyvesant Park to packs of wild dingoes in Australia who have been known to attack humans. The audience booed him.

An article in Governing Magazine, which tracks trends in local government, cites dog regulations among the most rancorous issues cities face today - on the same level as taxes.

The limited amount of park space in New York makes dog runs a particularly difficult issue, according to former Parks Commissioner Henry Stern, who helped found the city's first one in 1990.

"It's simple," said Stern. "For dog owners, they are a pleasure. For others, they are a nuisance."

FIRST RUN

New York City's health code forbids animals from being off a leash, but for years dogs have been allowed to run free in certain parks. When incidents do occur - people or other dogs get bitten, flowers are dug up, or poop goes unscooped - the Parks Department or police often respond with a crackdown on leash law violators.

Following a series of complaints and a crack-down on free-range dogs in the early 1990's, former Commissioner Stern came up with a compromise that would allow for some off-leash hours at certain locations.

Thus the city's first dog run came into being - aptly named "First Run" - in Tompkins Square Park in the East Village.

Today, there are 26 official dog runs in the city, according to the Parks Department. Central Park features some gathering places for dogs, but no official fenced-in runs.

Prospect Park in Brooklyn provides one of the largest and most lenient off leash areas in the city. But that's not enough for some Brooklynites. "There are many many owners who, for a variety of reasons, cannot let their dogs off leash in wide open spaces," writes Elizabeth Heeden, calling for an enclosed dog run in the park, on the Park Slope Gazette, one of Gotham Gazette's interactive community pages.

Proponents contend that in addition to creating a place for pets to play, dog runs are where New Yorkers can meet and build a sense of community. In this way, dog runs are not really about animals, according to Jeffrey Zahn of the New York Council of Dog Owners Group, which represents some 15,000 dog owners in the city; they are about people.

"A common mistake is that the issue is about the dog's rights, when it's not," said Zahn. "Dog owners are just one of many groups in the city competing for a limited amount of space."

Opponents counter that dog runs are a smelly, noisy, and poor use of the city's limited parkland.

"It's dusty, dirty, and they act like they own the place," said Laurel Harrington, a student who frequently studies in Washington Square Park. "I like dogs and they're cute, but of all of the things that happen in this park, the dogs are the only thing that makes it smell."

Even some dog owners are wary of dog runs because they fear for the safety of their pets. One of the most popular topics on the message boards of the website urbanhound.com, which touts itself as "the city dog's ultimate survival guide," is berating owners who cannot control their pets.

"Washington Square Dog Run has been getting too rough lately because of the people who either don't watch their dogs or correct bad behavior," one posting reads. "It's not always a safe place for small dogs to roam freely. I cannot risk my smallest dog's life there any longer."

Then there are those owners - who the responsible dog people argue give others a bad reputation - that ignore dog runs completely, because they do not think their companions should be fenced in.

In 1996, a woman was arrested in Central Park for letting her Bichons Frises, named Baby and Sugar, run off leash. After trying to run away, the woman, who was married to an Italian count, was wrestled to the ground and handcuffed to a bench for 45 minutes. "It's not like a herd of wild dogs," the countess reportedly said. "And even if it were it's not like they don't deserve a place to run."

CREATING A CANINE PARADISE

About a year ago, Olivia Lee had a seemingly simple goal: she wanted to start a dog run for her beagle-mutt Max.

So Lee, who had no experience in such a civic project, selected a rarely used handball court in a park on the corner of 35th Street and Second Avenue as her chosen spot. She founded a website, www.murrayhilldog.com and collected over 700 signatures of support. But when she took the idea to her local community board, Lee realized her battle was just beginning.

"One person said, `I don't know if you are new to the neighborhood, Missy, but your dog run is not going to happen,'" Lee recalled. "The person actually called me `Missy.'"

Gary Papush, of community board 6, said that the board always considers serious proposals, but that frankly the neighborhood is facing more pressing issues.

"If David Letterman did a top ten list of the major concerns of community board 6, dog runs wouldn't make the list," said Papush.

The encounter between Lee and her community board is a common, and by New York City standards, fairly tame example of the tensions that exist over dog runs. Getting just a few square feet of park space set aside for pets can take years, hundreds of thousands of dollars, and a lot of political lobbying.

"It can take anywhere from six months to ten years to get a dog run," said Jeffrey Zahn of NYCDOG. "My advice is to keep a sense of humor and be patient."

Even though local community boards do not have the power to block a plan, they still often hold the key to whether a plan is approved or rejected. If a community board is in favor of a run, it has a much better chance of being approved by the Parks Department. (Click here for a step by step guide to starting a dog run.)

But it is not just founding a dog run that takes effort; it is maintaining one after it is approved. The city's dog runs operate like miniature governments with their own elected leaders, rules, and committees.

One of the most successful, and well respected, organizers in the city is Mary McInerney, who runs FIDO, the Fellowship in the Interest of Dogs and their Owners.

Five years ago, many city parks began putting an end to off leash hours. Prospect Park in Brooklyn has no dog runs, and so McInerney approached Tupper Thomas, the administrator of Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and offered to self-police dog owners. Now each evening, hundreds of dogs and their people enjoy off-leash hours in several meadows. In return, the owners must abide by a strict set of rules including keeping their dogs under control, picking up waste, ensuring no holes are dug, and staying away from horses and ball fields. The fine for breaking any rule is $100.

McInerney's mission is not only to educate owners in "responsible supervision," but to be a kind of liaison to anti-dog New Yorkers.

"Some people are afraid," said McInerney. "A lot of people who live their lives in the city have had a limited experience with animals, whether it's dogs, cows, or ducks."

POWER TO THE PUPS

While dog owners may not enjoy the political power of real estate, labor unions, or racial voting blocs, dog owners do make their presence known in local politics.

In 2001, the New York Council of Dog Owners Groups (NYCDOG - pronounced "nice-dog") organized a rating system for local candidates to make sure they were educated on leash laws as well as rent regulations and tax policy.

Over 80 candidates responded - including three Democratic mayoral candidates Fernando Ferrer, Peter Vallone, and Mark Green. Michael Bloomberg received a rating of "In the Dog House" for his failure to answer.

At a recent forum on how to run for political office, West Side City Councilmember Gale Brewer spoke to a room of future candidates and told them that along with fundraising, organization, and a rolodex full of contacts, dog runs were an essential part of a successful campaign in New York City.

"I don't own a dog," said Brewer, "But I hit the dog runs so often that when the dog groups did their endorsements, I got four paws."

Do you have issues with dog runs in your neighborhood? Visit the Community Gazette homepage, find your neighborhood, and post a message under "COMMUNITY VIEWS – Ideas to Improve Your Neighborhood."

RELATED LINKS

• New York Pet Policies (Gotham Gazette)

• Urban Hound - City Dog Survival Guide

• Dog Lawyers

• Ratings of NYC'S Dog Runs

• New York Council of Dog Owner Groups

• Parks Department Dog Run Info

• Dog Licenses

RELATED ARTICLES

• Sidewalk Cafés

• Car-Free Parks

• It Happens Every Spring (Overview)

Car-Free Parks

|

|

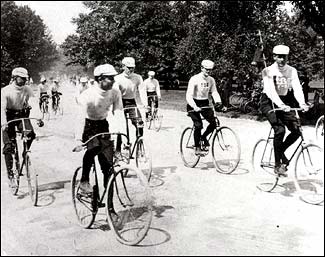

| A bicycle club enjoys the Central Park drive in 1895, four years before the arrival of the automobile. (Photo courtesy Transportation Alternatives.) |

In 1899, the newly-formed Automobile Club of America was granted the first permit to drive a car in Central Park. For the previous five decades, only pedestrians, bicycles, and horse-and-carriages had been allowed.

Many New Yorkers did not like cars in the park then – a 1906 letter to the New York Times bemoaned the "ugly, noisy, and evil-smelling" automobiles – and some still don't like it today.

Nearly a century and a half after they were built, some would like to see Central Park and Prospect Park in Brooklyn returned to their original purpose.

"The parks were not designed for cars," said Aaron Naparstek of the organization Transportation Alternatives, which has been lobbying for car-free parks for the last 20 years. "Because of the curves, you can only see 40 to 50 feet in front of you, which makes driving dangerous."

There have been accidents in the past. A woman cyclist was struck and killed by a van in Prospect Park in 1997. Two people were hit in Central Park in 1998.

Both Central Park and Prospect Park already have some car-free hours. Automobiles use the drives during morning and evening rush hours during the summer. (See blue box for car-free hours)

But advocates want to ban cars 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Opponents argue that banning cars from the parks completely would actually make the city less livable. Automobiles would be forced onto side streets, creating havoc for drivers and the surrounding neighborhoods.

"I simply don't see a compelling public need that justifies displacing thousands of cars into the surround area," argued Alvin Berk of Brooklyn's community board 14.

THE POLITICS OF CAR FREE PARKS

Support for car free parks has been growing in recent years. Environmental groups, running clubs, some former transportation commissioners, and the majority of the City Council members that represent the neighborhoods adjacent to both Central Park and Prospect Park are in favor of the idea.

But victories are still hard to achieve and even those are small. This winter the city agreed to close Prospect Park to cars for a few more hours a week as a trial period.

|

The major groups standing in the way, advocates say, are the mayor and Department of Transportation and the Parks Department.

"The Department of Transportation looks at those parks and sees unused road capacity," said Naparstek.

The city argues that it is balancing the needs of all New Yorkers with a compromise of car and pedestrian only hours.

"We want to balance the various needs of the residents so everyone can benefit," said Transportation Commissioner Iris Weinshall.

Until the mayor or the borough presidents hear enough outcry, there is little incentive for the parks to change their policies. And some of the most outspoken opposition comes from neighborhood residents or those who commute to work or school through the park areas.

Alvin Berk of community board 14 says residents fear not only more traffic, but also increases in accidents, higher exhaust emission in neighborhoods, and a reduced quality of life.

"It's not just a matter of inconveniencing drivers," said Berk. "Our concern is for the safety, well being, and health of residents."

BATTLES IN THE STREETS

Passions of drivers and pedestrians can sometimes run high.

During car-free hours in Prospect Park, some motorists have become so incensed, that they climb out of their cars, move the barricades blocking the entrance, and keep on going. Earlier this year, the park had to ask the 78th police precinct to step up enforcement.

And in their efforts to rid parks of cars, activists sometimes resort to environmental guerrilla tactics to battle their 3,000 pound steel enemies.

In recent years, activists armed with plants and banners erected a human barricade across Grand Army Plaza in Prospect Park. Or when a cyclist is killed, an outline of a body is often spray-painted on the city street.

And each month, bicyclists gather for what they call Critical Mass to ride as a group through the city streets, boxing in cars, and blocking intersections to protest for pedestrian rights. At times, the groups grow to include hundreds of cyclists, who will stop in the middle of a major intersection, lift their bikes into the air and chant slogans like "No More Cars!" while motorists honk their horns and curse.

Do you have issues with cars in your parks? Visit the Community Gazette homepage, find your neighborhood, and post a message under "COMMUNITY VIEWS – Ideas to Improve Your Neighborhood."

RELATED ARTICLES

• Dog Runs

• Sidewalk Cafés

• It Happens Every Spring (Overview)

Reviving the Filtration Plant Underneath Van Cortlandt Park

The Bloomberg administration has been quietly working to resuscitate the controversial plan to build a water filtration plant under the Mosholu Golf Course in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. That plan was declared dead a year ago, when the State Supreme Court ruled that building in the park was an "alienation" requiring approval by the state legislature. By tradition, the legislature almost never approves the taking of parkland over the objection of the legislators from the district where park is located.

The city needs to build the facility in order to comply with an order from the federal Environmental Protection Agency to filter and treat the part of the city’s water that comes from the Croton watershed. The city is under a court order to come up with a plan by April 30th.

The New York Observer reported that the administration has been lobbying Bronx elected officials for months, and has gained the support of two key politicians, Assembly member Jose Rivera, the Bronx Democratic county leader, and Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion. According to the local Bronx papers, Christopher Ward, commissioner of the city Department of Environmental Protection, met with Bronx members of the Assembly at the Bronx Democratic Party headquarters in March to present his department’s case for putting the plant in Van Cortlandt Park. He said that it would save the city between $200 and $500 million over the alternative sites, and keep jobs in the Bronx.

The agency has scaled back the original plan, reducing its size and putting it completely underground, with the golf course’s driving range rebuilt on top. The original design called for the plant to rise to a height of 30 feet at one end. Originally, the Mosholu Golf Course was to be closed during the four years of construction, but the new plan would keep it open, although the driving range would still be closed. The department has also made promises of greater funding for Bronx park projects.

The city says that the plant could be built more quickly at the Van Cortlandt site because all the environmental reviews have been completed. Park advocates dispute that, saying that because of the changes in the plan a new Environmental Impact Statement is required. They also note that new security issues have arisen since September 11, and want to know how the city would be able to allow recreational use on top of and next to a potential terrorist target.

Assembly member Jeffrey Dinowitz, who represents the district, and local residents are outraged at the Bloomberg administration’s efforts to fast-track alienation legislation, and are organizing to fight the project all over again. Park advocates are concerned that putting the filtration plant in Van Cortlandt Park could set a dangerous precedent. "We can’t take parkland because it’s the cheapest option – it’s always going to be the cheapest option for the city," said Christian DePalermo, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks, a citywide parks advocacy group. "It’s land held in the public trust."

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.