Taking Back the Park from Crime

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

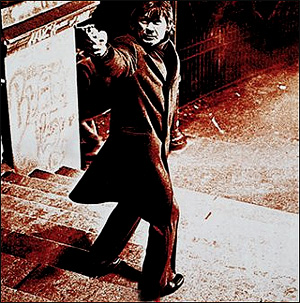

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

Kane's murder was the first of the homicides whose inherent brutality seemed incalculably worsened by their senselessness -- and their location in the Eden of Central Park. In fact, journalists since the 1930s have used incidents in Central Park as powerful symbols for urban crime in general.

The truth is, though, that, like the city itself, the park has been safe for most of its history -- until the "rogue crime wave," to use historian Eric Monkkonen's words, that engulfed New York between 1958 and 1991 and found Central Park to be a particularly tractable host.

And the first chapter in New York City's much heralded, triumphant campaign against that crime wave began in Central Park in 1980. Years before Rudy Giuliani was elected mayor or Bill Bratton appointed police commissioner, the team of officials overseeing Central Park devised a strategy for making Central Park safe again.

CRIME WAVE

In 1965, Robert Lowell published his poem "Central Park," which displayed the 1960s' odd combination of fear of violent crime and contempt for cops:

"We beg delinquents for our life.

Behind each bush, perhaps a knife;

each landscaped crag, each flowering

shrub,

hides a policeman with a club."

The design elements that helped make the park a refuge from the city -- secluded woodlands, hidden coves, paths that curve and dip from sight, Lowell's flowering shrubs -- also made the park hard to protect or patrol. Central Park's fame and beauty made it a prized site for concerts, protests, marches, rallies and celebrations. But the huge crowds also attracted crime.

These two factors, combined with public and police tolerance of so-called petty crime during the 1960s and 1970s, led to a wave of muggings and vandalism in the park that New Yorkers noticed -- and feared. Faced with public concern, park officials during the Wagner administration mowed down shrubs and removed trees from areas where muggers were thought to lurk.

And more draconian proposals were also put forward. Wagner's parks commissioner, Robert Moses, suggested building a senior center in the wooded Ramble in order to halt both gay sexual encounters and violent assaults on gay men.

The idea of the park as sanctuary faded as crime soared. In the 1960s and 1970s, felonies in the park surely averaged at least 800 to 900 a year; we cannot know for sure because it was so difficult for victims to report crime. The park had almost no functioning call boxes or public phones. Reaching the police precinct house in the park by foot was nearly impossible from many sections, even the adjacent Great Lawn. And those intrepid victims who managed to make it to the precinct house were often discouraged from filing criminal complaints.

WAS CENTRAL PARK EVER THAT DANGEROUS?

Many commentators today note that, for some time, the Central Park precinct has had the lowest crime figures in the city. Last year, for example, Central Park had only one of the city's 584 murders, and only 5 of the city's 2,024 rapes. Indeed, for all of 2002, Central Park (PDF Format) had only 132 major crimes -- a 72 percent decrease from 1993. The city as a whole had 153,682 major crimes in 2002 -- or a 64 percent decrease from 1993.

But comparing Central Park to other precincts isn't really fair. It not only has no resident population, making the calculation of crime rates impossible, it is closed at night, while all other precincts remain open for business, and crime.

Central Park's crime numbers are very low, which is wonderful. But in important ways, the problem never was simply the numbers of major crimes. Instead, Central Park has been plagued by three distinct crime problems.

First, it has always attracted heinous crimes that became highly publicized and discussed because of Central Park's symbolic importance, and its location in the middle of New York City, the nation's media capital. The three national television networks, for example, were headquartered within walking distance of the park. Their broadcasts, as well as Johnny Carson's regular nightly attacks, probably exaggerated the extent of Central Park's crime. But there is also no doubt that crime in the park was a real problem.

Second, public events such as concerts or parades have often resulted in rampages by young men. The low point of the park's early restoration occurred on July 21, 1983 -- exactly 20 years ago -- when, following a poorly organized concert by Diana Ross, hundreds of young men tore through the park and its neighboring blocks, assaulting anyone they encountered. A family that had just flown in from Paris for vacation told the New York Post that they had been assaulted and robbed by a gang of 20 teenagers. When, bleeding and bruised, they asked a cop for help, he told them, "That's life in the big city," and walked away.

Warner LeRoy, the owner of the Tavern on the Green, said that dozens of teenagers climbed onto the restaurant's roof and leapt down to the interior patio, where patrons were eating. They jumped on tables, stabbed diners, and stole purses and bags, before swarming back over the patio walls. Known as "the night Central Park got mugged," July 21 resulted in very few arrests -- or recorded crimes.

The third kind of troubling Central Park crime is the vast area of relatively minor crime, such as purse snatchings and bike thefts (before bikes cost thousands of dollars). A poll in 1983 found that over 65 percent of regular park users had experienced some "encounter" with crime in the park. Less than 5 percent said they had reported the incidents, assuming the cops would just dismiss them anyway. And seven percent of regular users said that they carried a weapon in Central Park.

MAKING CENTRAL PARK SAFE AGAIN

The team that began Central Park's rescue in 1980 included Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis, Central Park administrator Elizabeth Barlow (Rogers) and the captain of the Central Park Precinct, Carl Jonasch. They saw the safety of Central Park users, and of the park’s physical plant, as essential to the park's renaissance. They were practical people. No amount of restoration was going to work if the park was dangerous. Donors would not give millions of dollars to restore park treasures that were just going to be vandalized all over again. Nor would donors be enthusiastic if they and their fellow New Yorkers were afraid to enter the park to see the fruits of their gifts. The park had to be revived as the haven that Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux had envisioned in the 19th century.

The team faced many impediments, an ominous one being that the Central Park precinct itself was a sorry mess. Housed in a badly maintained converted stable that reeked of urine on humid days, Central Park cops were often a demoralized, tired lot. Ambitious cops avoided being assigned to Central Park, which offered few chances for career-making arrests. Instead, the precinct attracted many who were eager to pass their final years before retirement peaceably. When they had to patrol, they stuck to their cars. There was not much pressure to get out of the cars since the 911 system, implemented in 1972, had centralized dispatch, removing it from the precinct.

Jonasch set out to change things. He was an athlete and one of the first cops to run in the park. He wanted cops to know the park as users rather than as drivers, a revolutionary idea. And he wanted the cops to get out of their cars and patrol on foot or scooters. He met with serious resistance.

But at the same time, Commissioner Davis started the ranger program, creating a uniformed force that would patrol the park and educate park users, concentrating on the quality-of-life issues that cops deemed beneath them. In 1982, Davis added Park Enforcement Patrol (PEP) officers, who could issue summonses for infractions of park rules. Both the rangers and PEP officers visibly patrolled restored sections of the park, enforcing high and previously unknown standards of behavior, such as no ball-playing on Sheep Meadow.

But the conceptual breakthrough in making Central Park safer was the now-familiar but then brand-new broken-windows theory of policing. Harvard professor James Q. Wilson said that cops underestimated the seriousness of disorder, whether the physical disorder apparent in vandalism, graffiti and neglect or the disorder of people behaving badly. The police had to take small signs of disorder seriously and deal with them. That could mean handling small-time offenders, confronting physical disorder or some combination of both. Police could not dismiss disorder as "petty" because petty had a way of growing serious.

Just after the March 1982 publication of his Atlantic Monthly article propounding this idea, Wilson gave a lecture to New York police brass about implementing his theory of policing. Jonasch argued this new approach would be ideal for Central Park.

Crime was still high in 1982, over 700 robberies and 9 murders, when Captain Jonasch set the new strategy for the park. Even as the park seemed to get safer every year, however, horrible crimes punctured its serenity.

In May 1985, gangs of teenagers attacked participants in a March of Dimes Walkathon. NYPD Captain Ray Vignola called them "jackals on the velt." In July 1986, Officer Steven McDonald was shot, and paralyzed, when he stopped a group of teenagers on the East Drive In April 1989, the Central Park Jogger (now known to be Trisha Meili) was beaten, raped and left for dead. On the same night, dozens of youths rampaged through the park, assaulting and robbing park users.

Since then Central Park has reflected the overall drop in crime in the city, although crime has not disappeared entirely. The park was, for example, the scene of attacks on women following the Puerto Rican day parade in June 2000. The lessons from Central Park are pretty clear. It is now probably the safest and the most beautifully restored of the world's great parks. But only constant vigilance will keep it that way.

Julia Vitullo-Martin, who writes Gotham Gazette’s topic page on crime, is a long-time editor and writer on urban affairs, and the co-author of a study on Central Park security conducted for the Central Park Conservancy in the early 1980's.

Dancing in the Park

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

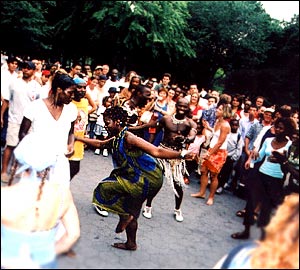

I usually enter through a gateway of benches at West 110th Street and roll on my inline skates past picnickers, tennis courts, the castle and the Boathouse Café. Every year, I promise myself a detour for a pick-up game of volleyball in the worn grass across from the reservoir. But instead, every weekend, my destination is always the same -- the African Drum and Dance Circle near the Band shell.

I was intimidated when I first encountered the African drummers in Central Park six years ago. The music and faces were different. They were from Senegal, Mali and Ghana. The circle made me wonder if I was out of touch with who and what I was as an African-American. The beat touched a primal nerve, reverberating in the torso, echoing in the ears, and I couldn’t help dancing on my skates to the drums. I did not know how the drummers would react, or what I would say or do if they said something to me.

Now I feel at home dancing in the drum circle. I have bonded with the African drummers and the other members of the circle, through languages, cultures, incense and comfort zones that intermingle and in some instances collide there.

The music beckons passersby from all corners of the park. It is a legal intoxicant that causes foot-tapping, finger-snapping, hip-swaying and losing track of the time. The drum circle lowers inhibitions as people cross ethnic, religious and economic boundaries and dance. There is no need for red tape, velvet ropes or government polices. The circle is its own world. The only rule is to enjoy. Flailing of bodies, heavy breathing, and sweating is encouraged.

There is no special training or equipment needed to dance in the center or off to the side. It is

as simple as taking a deep breath, smiling and stepping back into the enclosed area. The drum circle is a family of brothers and sisters who aren’t keen on parental figures. The aim is unity without a pecking order. There is harmony among the core drummers

and dancers, yet there are periodic challenges from outsiders seeking to strike a sour note.

There is no special training or equipment needed to dance in the center or off to the side. It is

as simple as taking a deep breath, smiling and stepping back into the enclosed area. The drum circle is a family of brothers and sisters who aren’t keen on parental figures. The aim is unity without a pecking order. There is harmony among the core drummers

and dancers, yet there are periodic challenges from outsiders seeking to strike a sour note.

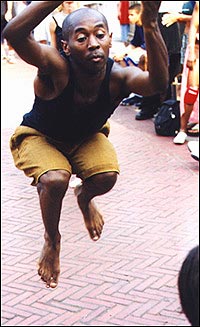

Prior to dancing with the drum circle, I can’t recall a time when I was airborne without being on an airplane or tossed in the air by an older cousin. The drum circle was the first time I was compared to a puppet without its strings, or having coils in my legs instead of bones.

I leave the circle physically exhausted, yet looking forward to the next weekend. Central Park and the circle have kept me happy and alive.

Kendall Williams is a freelance writer, editor and English as a Second Language tutor.

Central Park at 150

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

When New York City decided 150 years ago to build Central Park, it launched a project that became the model for city parks throughout the country. A major undertaking for the city, as Morrison Heckscher of the Metropolitan Museum of Art points out (“Birth of the Park”), Central Park was both a masterpiece of landscape art and a social experiment, a place where people from all walks of life could come together to enjoy a respite from the strains of urban life. After the park opened in the winter of 1858, every city in the country wanted its own version, and the American parks movement was born.

Today Central Park is cherished by the many New Yorkers who come to the park to escape from the rest of the city ("An Escape from Reality" By Sarah P. Lustbader), to appreciate nature, to form new communities (“Dancing in the Park” by Kendall Williams) or to make art (“Our Project For The Park,” by Christo and Jeanne-Claude). And Central Park remains a national model. The park’s rebirth over the last two decades, accompanied by a dramatic drop in crime within its boundaries ("Taking Back the Park from Crime" by Julia Vitullo-Martin) has shown other cities how they can restore their public landscapes. The Central Park Conservancy, begun by Betsy Barlow Rogers in 1980, pioneered the concept of a non-profit community organization raising funds and working with government to fix up and maintain a public park. Parks throughout the city and country -- even the national parks -- have adopted this idea of public-private partnership.

The very success of the Central Park model, however, raises some concerns. The reliance on private funding could weaken the government's traditional role in maintaining public space and ultimately reduce the opportunity for all citizens to enjoy it. Although Central Park has remained the quintessential public space, in Bryant Park, for example, private events held in the park temporarily keep much of the public out.

The reliance on private funding could leave the city with a two-tier park system. Individuals and corporations are most likely to donate to a park they care about, favoring parks in affluent areas. Despite efforts to provide private funds for the rest of the system, such as the non-profit City Parks Foundation, parks in poor neighborhoods, particularly outside Manhattan, could be left to depend on dwindling public dollars.

The activism of the Central Park Conservancy has fostered beautifully maintained grounds and funded many public performances and educational programs, "setting a standard to be achieved for the entire city park system," said Christian DiPalermo, director of New Yorkers for Parks. This has raised New Yorkers' expectations for all of the city’s parks. "You can't have Central Park with a completely different set of policies as the rest of the system," said Ethan Carr, a visiting professor in the Bard Graduate Center's landscape history program. But bringing the condition of all parks up to the level of Central Park would require the city to greatly increase its funding for parks, something it did not do even when the economy was thriving.

It is not only in fund raising that Central Park serves as a model. The conservancy, which operates the park under a contract from the city parks department, is in the forefront of park management as well. The conservancy does not just raise money – it runs the park and hires most park employees. The city parks department has ultimate oversight but does not manage Central Park as it does most other city parks.

The restoration of the park has been guided by a master plan, something urban park expert Peter Harnik says is key to a well-run park. And unlike the parks department in New York and many other cities, the conservancy plans for the long-term upkeep of areas that it has restored, protecting its capital investment and minimizing costs in the long run.

The park has had great success with its innovative "zone management" system, where one gardener is responsible for a specific section of the park. The gardener has the authority to enforce rules – such as prohibitions against trampling newly seeded areas, littering or letting dogs run loose – and is someone to whom visitors can complain or report problems. Doug Blonsky, the administrator of the park, said the zone system “works wonderfully in developing relationships with the community."

Any controversy within Central Park’s boundaries – be it crime, turning a blind eye to wine drinkers in the park while ticketing beer drinkers at the beach, or installing a work of art on its walkways -- immediately gains prominence because this is, though not our biggest, our most beloved and most used park. But a century and a half after it was first created, Central Park continues to inspire. The question is whether the New York City park system as a whole can benefit from its example. Ethan Carr said, "If we are going to call Central Park the great success story of American parks in the last 20 years, we have to find out how that can be extended throughout the New York City park system."

Anne Schwartz is the parks columnist for Gotham Gazette