How Park Improvements Affect Community Real Estate Values

Investing capital funds in parks can generate significant economic returns in the form of increased property values, but New York City is not making the most of this opportunity, according to a study released at the Great Parks, Great Cities conference, an international urban parks conference held in New York City last month.

The study, conducted by the accounting firm Ernst & Young and the advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks, selected at random 30 parks from all over the city and analyzed the relationship between capital investments and how tax assessments differed between parts of the same neighborhood closer and farther from the park over the past ten years. It also chose six different parks, at least one in every borough, to examine more closely as case studies, looking at capital funding, planning, and community involvement and comparing real estate prices, tax assessments and turnover rates in areas next to the park with those in the broader neighborhood.

A more thorough analysis also would have included the maintenance dollars allocated to each park, but this data was not available because the parks department uses roving crews for most park maintenance.

The analysis found that simply upgrading a park does not automatically add value to the surrounding area. From the sample of 30 parks, 55 percent of the 15 parks with the largest capital expenditures had either no increase or a decrease in the value of the real estate surrounding them. "The conclusion was that you cannot just throw money at a problem and expect to get results," said the project’s director, Glenn Brill, senior manager of real estate advisory services at Ernst & Young.

The detailed case studies showed that capital spending has higher economic returns when it is part of a larger plan for the community and includes long-term maintenance as well as the involvement of local residents and organizations.

The best example of this in the study is Prospect Park in Brooklyn, where $103 million – including $78 million in city funds -- has been invested since the 1980s. The Prospect Park Alliance, a public-private partnership that operates the park, has planned and overseen the park’s gradual restoration, working together with a wide range of community organizations. It also raises private funds to help maintain and program the park. The study found that the gap between the average single-family home sale price in the "park impact area" of adjoining Park Slope and comparable areas of the neighborhood farther from the park widened dramatically from 1996 to 2000. Before 1996, prices closer to the park were from 90 to 170 percent higher. Between 1996 to 2000, the price spread increased to 300 to 600 percent, before leveling off to 150 percent as prices farther from the park continued to rise.

Brill said that the research underlined the need for the city to take a strategic approach to investment in parks and coordinate it with other aspects of community development, like housing and policing. He also stressed the need for continued maintenance to preserve the city’s investment. "Our study supports the concept that a well-maintained park can make a significant contribution to real estate values," he said. "In doing so, it’s generating wealth for the owners and certainly a portion of it will be recirculated through the New York City economy."

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Our Project for the Park

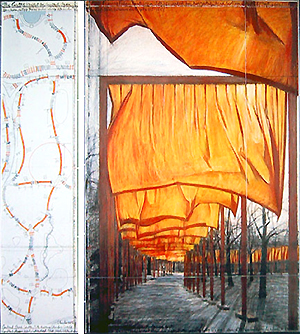

2002 Christo

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

We create works of art of joy and beauty that have no purpose whatsoever -- like all true art. It gives us great joy to do this -- and if the public enjoys it, it is a bonus.

We have chosen Central Park for one of our projects because we have lived in SoHo for the past 40 years at the same address, and New York is our town. We wanted to use Central Park because it is in the heart of the city. The 23 miles of walkways we are using go over the entire park from one of the richest streets in the world -- 59th Street -- all the way to Harlem and Spanish Harlem. The diversity of the people living around the park is extraordinary.

There are many parks in the five boroughs of New York City but Central Park is the only one that is totally cut off from anything natural. Riverside Park is by the river, a natural element. Prospect Park is surrounded by lovely houses that have gardens so the trees of the park and the trees of the gardens are mixed together. But Central Park is absolutely cut off from any other natural element. It is a pillow of green encased in concrete.

The Gates Project was started in 1979. It took 24 years to get the permit. Thanks to Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Patty Harris, the deputy mayor, we now have the permit. Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe and park administrator Douglas Blonsky also have been unbelievably helpful.

One hundred fifty years ago when Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted started designing Central Park they surrounded it with a stone wall but they left openings to allow the public to enter the park. There are no gates, but Mr. Vaux and Mr. Olmsted called the interruptions in the stone wall gates and gave them names: Boys’ Gate, Girls’ Gate, Engineers’ Gate, Warriors’ Gate, etc. So the word “gate” comes from Mr. Vaux and Mr. Olmsted.

In our Gates Project, we are going to place 7,516 gates along walkways in the park. The gates are made of vinyl poles 16 feet tall and 5 inches by 5 inches square. The fabric panels, made of a nylon called ripstop, will hang from the horizontal top bar. The project will be ready the second half of February 2005 and will remain in place for 16 days.

This is absolutely a project for Central Park. The geometric pattern of the city blocks -- hundreds of them, all very rectangular -- surrounding Central Park are in harmony with the geometry of our gates. Our gates are perfectly rectangular, a reminder of the geometry of the blocks all around Central Park.

We are using only the walkways for the gates. Mr. Vaux and Mr. Olmsted designed the walkways in a serpentine, noodle-like shape. The fabric panels moving capriciously in the wind will create many round, voluptuous serpentine shapes, a reminder of the design of the walkways.

This project will be in February, the only month of the year in which we can count on there being no leaves on the trees and so from far away you will be able to see the saffron colored fabric.

We are paying for the project ourselves as we have done for all our previous projects. We never accept sponsors.

To prepare the gates, we have rented an assembly plant in Maspeth, Queens. That is where 5,290 tons of steel, 65.11 miles of vinyl poles and 165,352 bolts and self-locking nuts will be delivered along with 15,032 steel leveling plates so we know the gates will remain vertical. One million ninety-two thousand square feet of fabric will be sewn into 7,516 panels, which means 54.11 miles of hems.

Each one of our gates is already numbered and positioned on our engineering map. We did that last June.

On January 3, 2005, we will enter Central Park. Steel weights that will support the gates will be placed on the hard surface of the walkways. We will not dig any holes. Professional workers with forklifts will distribute the steel bases. Each base weighs 700 pounds, and for each gate you need two -- 1,400 pounds. The workers have to deliver them to the exact position according to our engineering drawings.

Then we have a large number of unskilled workers, usually many students who come either on their own or as a class project. Everybody is paid. We have no volunteers.

They will secure to the steel base the assembly made of the two vertical poles and the upper horizontal pole. The fabric panel will be attached to the upper horizontal pole but you will not see it because it is restrained in a cocoon.

Those workers -- probably 700 of them, we don’t know yet -- will elevate the gate, bolt it to the bottom weight and leave the fabric restrained in the cocoon. Each team of seven or eight people will be raising between 70 and 100 gates. By Friday, all the gates should be standing secured, but you still will not see any fabric.

Then on Saturday morning the teams will open all the cocoons. The fabric will be freed. We hope that in one long morning the entire park will have the gates completed.

Then these people will remain as monitors to assist the public and answer their questions. They will distribute hundreds of thousands of fabric samples for free as we do at every project because the public enjoys having a little souvenir.

Then, after 16 days, the monitors will do the reverse work. They will take down the gates, remove them from Central Park and by March 15 everything should be gone and the materials will be recycled.

Christo & Jeanne-Claude are artists who have worked together for more than 40 years. They are best known for their large-scale projects, including “The Running Fence,” a curtain/fence of fabric stretching more than 24 and a half miles from the inland town of Cotati, California to the Pacific Ocean; “Surrounded Islands” in which 11 islands in Florida's Biscayne Bay were surrounded with 6.5 million square feet of pink polypropylene fabric; and the “wrapping” of the Pont Neuf in Paris and the Reichstag in Berlin.

Birth of the Park

Late 19th century, photographer unknown.

From "Central Park in Blue" at the Museum of the City of New York, one of several current exhibition about the Park.

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

Manhattan real estate is rather precious, so this was a momentous decision that took a great deal of political will. It required a general consensus among the population and the politicians that there had to be a park.

The need for a great central park in New York City goes back to the beginning of the 19th century and the creation of the grid plan in Manhattan. In 1807, the city was on the cusp of growth. Astute city builders knew that Manhattan's location, the quality of it port, the proximity of the Hudson River, and the idea that there would be an Erie Canal, would make this the city of commerce in America and that growth would be extraordinarily rapid.

The challenge was how to plan for it, and the planners came up with a very practical and logical scheme: 12 broad, north-south avenues and 155 narrow, east-west streets from Houston to 155th Street. This plan was imposed upon a very irregular, rocky, somewhat hilly landscape but had nothing to do with any of the natural topographical features. The only open of any size was between 23rd and 34th streets. Called "The Parade," it was a place for the local militias to exercise. By 1830 this park was gone, and because of great pressures of real estate development, all public land had disappeared.

Even the most stalwart builder knew that the city was going to require some sort of a park for peace and safety. People were beginning to think there had to be some reaction to the total control of Manhattan by the grid-planning of 1811. Andrew Jackson Downing, the editor of a very important magazine called The Horticulturalist, who had the ear of lots of Americans, started editorializing that New York needed a park of at least 500 acres. William Cullen Bryant, a leading poet and journalist, also editorialized about the need for major park.

By the 1851 mayoral elections, both the Democrats and the Republicans campaigned for a public park. The question was where, how and what is it going to look like.

Two locations were considered. One was Jones' Wood, a plot of land on the East River that was about 150 acres and pleasantly landscaped. You could easily put up a sign that said "New York Park," let the people in, and you would have been done. But it was not central, it only would have served a certain area, and it was not big enough. People like Andrew Jackson Downing said, "This is inadequate; it will not do."

The other choice was the site that we know today. It was already the site of the first great public works project in New York City, which was the Croton Water System. In the mid-1830s, the city found that if it did not come up with a municipal water supply that was adequate and sanitary, the city could not grow.

So a huge public works project was completed in 1842. Water from the Croton River in Westchester County was brought 42 miles across the East River into the Receiving Reservoir between 6th and 7th avenues, between 79th and 86th streets. From there it went down to 42nd Street and 5th Avenue to the Distributing Reservoir on the site of what is now the New York Public Library. By 1853, the managers of the Croton System began to survey for a huge North Reservoir, which still exists today north of 86th street.

There was a compelling logic that if you were going to take land from the private market for a park it should be tied in with the two reservoirs so the land between them would not be wasted. This was the anchor upon which the park was based. The receiving reservoir, which was filled in in the 1930s, is now the Great Lawn -- the park’s geographical center.

In 1853, everyone had agreed that the land around the reservoirs would be the place for the park. It would be about 848 acres, big enough to suit the requirements of landscape architects.

But it was a very unprepossessing piece of real estate. No one would have chosen it for its beauty or charm. It was rough, rocky and swampy, and it required a vast amount of work to make it into what it is today.

A board of commissioners for the park was established and hired a very accomplished engineer named Egbert Viele. He surveyed the area of the new park and did a pen-and ink drawing in 1855 of a design for a drainage system.

Meanwhile, in 1852, A.J. Downing had died saving victims of a tragic accident that occurred when two steamboats got into a race on the Hudson River. Just the year before he had brought back from England a young man named Calvert Vaux, a trained architect. Vaux looked at Viele’s design, which had been accepted, and said, “This is terrible. This is not adequate. Downing would not approve.” He began politicking behind the scenes and persuaded the commissioners to drop the plan and have an open competition.

The competition was announced in 1857, and 33 proposals were submitted in the spring of 1858. Twelve of the 33 were done by people who were already involved with the creation of the park. Few of these proposals have survived.

The proposals had to honor and incorporate 10 requirements. There had to be a playground, a parade ground, a cricket ground, a flower garden and a group of buildings for exhibitions.

How did Calvert Vaux, having started the competition, get into it himself? He realized he did not have the ability to do the whole thing himself. He did not know the topography well enough. And he also knew that if he were lucky enough to win, he would not have the ability to execute the plan. So he found Frederick Olmsted, who had lost all his money by investing in a publishing business and then ended up as superintendent of Central Park in 1857. Olmsted was working everyday in the park on horseback and knew everything about it.

Vaux persuaded Olmsted to join him in drafting a proposal for this competition. The two of them worked together every evening through the winter of 1857. Their entry was the last submission, and they won.

Vaux and Olmsted included all the things that the competition required: a parade ground, a playground, a flower garden, a conservatory, a museum area, cross streets, a skating park. But all of this was of no real interest to Vaux and Olmsted. What they saw was an opportunity to transform this piece of raw, rocky, narrow, very unsympathetic nature. They were given the worst possible playing deck of cards, the most unpromising piece of land, and that forced them to think outside the box.

The idea was to separate this piece of nature from the city entirely. Once you enter the park, you do not want the city to be included.

Vaux and Olmsted proposed great open areas, which they saw as beautiful landscapes; they saw it as a great, English, stately home meadow. This required major transformations of nature. Ten million cartloads of earth and rock were moved. Far more than simply creating a park, it was transforming nature into a work of art.

Vaux and Olmsted got the commission and went ahead with it. Theirs was a great partnership because they were complimentary in their talents.Vaux did everything architecturally. He designed all the buildings and the 35 or 36 bridges, most of which survive today and are the great glories of Central Park. The original design had only a half dozen bridges. But shortly after the plan was accepted, commissioner August Belmont said there needed to be bridle paths in the park. That requirement meant 35 or 36 bridges.

The biggest architectural component of the park was the Bethesda Terrace, which survives today and was one of the grandest public buildings in New York. It is virtually invisible unless you see it from the right angle; the point that Vaux was making was that architecture should always be subsidiary to nature in Central Park. And that may be why Vaux has, historically, been second fiddle to Olmsted. Vaux was not as charismatic, but he was crucial to the Central Park’s creation.

Central Park cost about $10.5 million. This was big money at the time -- the land alone cost more than $1.5 million. And in October 1857, times were really tough. How did they win approval for this huge public works projects.

The economic panic was a blessing in disguise because the politicians wanted to employ all these people who were out of work. Olmsted had up to 4,000 people on his payroll in 1859-61. It was not until 1862 and the Civil War draft that the numbers went down. Between 1858 and 1861, virtually the entire park up to 79th street, the most complicated part, was built. It was an extraordinarily rapid achievement using the best materials and no shortcuts.

The park was immensely popular from day one, and its constituency was as varied as the city -- and as varied as it is today.

Morrison H. Heckscher is the Lawrence A. Fleischman chairman of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This is adapted from a lecture he gave in conjunction with the museum’s exhibition, “Central Park: A Sesquicentennial Celebration,” which runs until September 28, 2003.