Reopening the 19th Century High Bridge

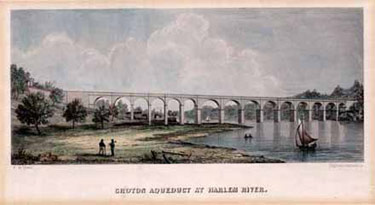

At one time, the High Bridge was known far and wide. Built in 1848 in the style of a Roman aqueduct, it carried water across the Harlem River. It was the most visible symbol of the city’s first water system, an engineering masterpiece that supplied abundant, clean water to a population previously dependent on fouled wells and subject to the twin scourges of disease and fire. Today, however, most New Yorkers have never heard of the High Bridge. Connecting Washington Heights Heights to the Bronx neighborhood of High Bridge, north of Yankee Stadium, it has been closed for decades, a forgotten historical footnote and a missing link between two communities

So it is fitting that the bridge, which helped New York City prosper into the 20th century, should play a role in Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s blueprint for making the city sustainable into the 21st. One of the specific environmental and infrastructure goals of PlaNYC 2030 (and one that doesn’t need the approval of the state legislature) is reopening the bridge. The city has allocated $60 million for the project, in addition to an expected $12 million in federal funding. When complete, the reopened High Bridge will be an asset not only for the neighborhoods at both ends of the structure but for the entire city.

The Rise And Fall Of The High Bridge

With its 100-foot-high stone arches crossing from cliff to cliff over the Harlem River Valley, the High Bridge quickly became a popular attraction. The pipes were decked over, and a walkway was added. People flocked to what was then the countryside to spend the day along the river and promenade across the bridge dressed in their finest clothes. A tourist industry sprung up with a ferry landing, beer gardens and inns. Boathouses, marinas and rowing clubs lined the river.

The city eventually expanded up both sides of the Harlem River, but parks were created where the bridge landed. The Manhattan side features the 116-acre Highbridge Park, which has a swimming pool on the site of an old reservoir and a recreation center. In the Bronx, a one-acre park of the same name overlooks the bridge and the wooded hillside across the river. When the water pipes were taken out of service in 1958, then-Parks Commissioner Robert Moses had the bridge itself transferred to the parks department.

The neighborhoods around the bridge declined and sometime around 1970, the city closed the High Bridge because of safety and maintenance concerns. (There is no evidence, however, to support the story that it was closed because kids threw rocks onto the Circle Line.) No one seems to have noted the date that a parks employee padlocked the gates for good.

Keeping The Dream Alive

Practically from the moment the bridge closed, Bronx and Upper Manhattan residents started trying to get back their river crossing. Around the city and within the parks department, too, people worked to promote the idea of reopening the bridge.

Ellen Macnow, coordinator of interagency planning at the parks department, has been one of the bridge’s most persistent advocates. “It happens to be, when you see it, a really fabulous place,” she said. “It reeks of history.” Macnow said that the effort to reopen the bridge first got traction with the 1993 New York City Greenway Plan, a proposed 350-mile network of pedestrian and bicycle trails that included the High Bridge.

Discussions between the parks department and the Department of Environmental Protection, which owns the now defunct water pipes inside the bridge, eventually led to a study by the Department of Transportation to determine the cost of restoring the bridge. Word spread, and more groups became involved. In 2001, the parks and environmental agencies and a number of nonprofit organizations working to improve the parks and trails in the area, including New York Restoration Project, Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct, and the City Parks Foundation formed the High Bridge Coalition.

A key to the effort was getting the residents of the two neighborhoods involved. In 2003, Partnerships for Parks, a joint program of the City Parks Foundation and the parks department, chose the High Bridge area as one of its Catalyst for Neighborhood Parks sites. This effort, focusing on neighborhoods with problematic parks, provides private funding for activities and events that in turn build community involvement in the parks and so help them attract additional public and private resources.

Joseph Sanchez, the Highbridge project coordinator, grew up in Washington Heights and recalls that, even as a child, he saw the potential and beauty in the local parks, “as ugly and dirty as they were.” To get people into the parks, he organized hikes, clean-ups and other activities, and brought in community groups to run sports and education programs. He also spread the word about the High Bridge and urged residents to join the effort to reopen it. “We began to hear stories from residents about how they once used the bridge, how they still want to use it,” said Macnow. Community members joined the coalition and began pushing to get the bridge restored.

In November 2006, the parks department announced that it would take the first steps toward opening the bridge, with a $5 million allocation of federal transportation money from U.S. Representative JosĂ© Serrano and $1.5 million in city funding. But before the project was included in PlaNYC, coalition members thought it would take years to complete the repairs. “We are on our way to reopening the bridge much faster than we had ever thought,” said David Rivel, executive director of the City Parks Foundation. “It really just captured the imagination.”

The restoration will include repairing the bridge’s patterned brick walkway, its remaining stone arches and the steel span that replaced four of the stone arches in 1928 to allow boats to navigate the full width of the river. The bridge will also be safer than it was in its heyday with wheelchair ramps and higher fencing.

A Green Future For The Harlem River

Opening the High Bridge will bring multiple benefits. To begin with, it will make Highbridge Park, with its enormous pool and improved recreation center, more accessible to residents of the High Bridge neighborhood in the Bronx, who have few nearby recreational options. Even now, many Bronx kids climb over the bridge’s locked fences to get to the Manhattan side.

The bridge could also become the focal point of a revival of the Harlem River as a recreational destination, said Drew Becher, executive director of the New York Restoration Project, a private-public partnership founded in 1995 by Bette Midler to reclaim neglected parks in upper Manhattan and the Bronx. “It will make people look down and see what a great Harlem River Valley we have,” he said.

New York Restoration Project has contributed to the resurgence of boating on the river through its Peter Jay Sharp Boathouse, the first new community boathouse in New York City almost a 100 years. The organization recently planted 200 of an eventual 3,000 cherry trees along the river, which, they hope, will rival Washington, D.C.’s cherry blossoms in the spring.

Reopening the bridge also will promote the greenest and healthiest way to get around the city. It will become a vital link in city’s partially completed system of bike and pedestrian trails, including greenways being built on both sides of the Harlem River. It will also fill a gap in the Old Croton Aqueduct Trail, the 41-mile trail following the route of the city’s first water system.

And not least, the High Bridge is a unique recreational space in itself, a place that belongs only to pedestrians and cyclists, with magnificent views of the river and the cityscape. “A stroll on the bridge is just such an incredible thing,” said Joseph Sanchez. “You feel like you’re in the middle of the world.”

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Grading Neighborhood Parks 2007

Conditions in New York’s small, neighborhood parks vary widely across the city. And despite some areas of improvement, overall the parks are in worse shape than last year, according to the recently released 2007 Report Card on Parks, from the advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks.

For five years, the non-profit advocacy group has been evaluating conditions in local parks, from one to 20 acres in size. Trained surveyors assess eight different "service areas" used by park visitors, like conditions of sports field, benches, and bathrooms. They rate each feature following criteria developed from a park user's point of view.

As in previous reports from the group, parks with access to private funding earned the highest grades. Bryant Park, which is maintained by the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, got a near-perfect 99. But the report also found that maintenance levels vary widely among parks relying only on public funds, that maintenance can be inconsistent even in the same park from one year to the next. A number of parks have chronically poor conditions.

In this year's report, the average citywide grade dropped to 70 percent, down from a rating of 80 percent in 2005.

"We don't get consistent maintenance year to year, month to month, or even day to day," said Christian DiPalermo, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks. "And that's because the system has been underfunded.”

Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe, however, called the report card a case of "grade deflation" and said that ratings for many parks were lower than the department's own inspection data indicate. "It flies in the face of reality, which is that parks continue to get better."

PROBLEM AREAS: TREES, DRINKING FOUNTAINS, GRAFFITTI

In addition to rating individual parks, the New Yorkers for Parks report looked at how the different elements fare citywide.

Among the areas that performed poorly this year were the "green" features: lawns, natural areas, and trees. The report recommended a greater investment in horticulture and forestry, areas that have received little funding in recent decades. At present, for example, park trees are pruned only on an emergency basis.

Once again, surveyors also found a litany of problems with drinking fountains, including lack of water pressure, leaks, mold, and basins filled with trash or broken glass. The average grade for all the drinking fountains surveyed was 40 percent.

Careless workmanship - sloppy paint jobs, poorly done repairs, and chipping or peeling paint - gave more than half of playgrounds, courts, fields, and sitting areas an unacceptable score for maintenance work.

The report also noted an upsurge in graffiti, which Commissioner Benepe confirmed. He suspects the increase is tied to a recent court ruling voiding the city's prohibition on selling spray paint to minors. The department has been working with the police and its Parks Enforcement Patrol to reverse the problem.

"Another thing we found is that playground conditions are starting to slip," said DiPalermo.

Ten years ago, the parks department made significant capital improvements to many playgrounds, he said, but wear and tear is starting to show because of insufficient maintenance.

GOOD NEWS: PATHWAYS, BATHROOMS, BUDGET

Parks do get some positive marks. Higher scoring park features included pathways and sitting areas, similar to previous years.

And despite the use of a more rigorous standard this year, the average grade for bathrooms held steady from 2005, a result of the parks department's focus on improving bathrooms through Operation Relief. More than 90 percent of the bathrooms inspected were open, compared with 50 percent four years ago.

Also this year, for the first time, the mayor's proposed budget for parks maintains last year's funding for areas like playground associates, tree pruning, and other maintenance, items that are usually eliminated and then restored during negotiations with the City Council.

As part of Mayor Bloomberg's ambitious greening blueprint, PlaNYC, the city is beginning to commit more funds to care for the city's trees and natural spaces.

Park advocates are lobbying for an additional $10 million for 250 to 300 new playground associates for parks that currently have no staff assigned. They are also asking $5 million more for forestry and $3 million to hire 60 full-time gardeners for specific parks.

THE PARKS DEPARTMENT RESPONDS

The parks department does its own ratings of green spaces through its Parks Inspection Program, which conducts 5,000 formal and 10,000 informal inspections a year.

Parks Commissioner Adriane Benepe said that the program, which allows the department to identify and fix unsafe conditions and other problems, has documented an upward trend in park conditions. Inspection reports can be found by park on the department's web site.

Commissioner Benepe agreed that some of the playground equipment was reaching its natural lifespan, but said that the department's inspection and repair program addresses problems quickly. He noted that a recent budget increase has allowed the department to hire 40 workers specifically to care for playgrounds.

"Contrary to the assertion that there is poor maintenance resulting from a declining workforce, the workforce is growing dramatically," he said. "By the next fiscal year, we will have added 1,000 full-time staff since Mayor Bloomberg took office, a 25 to 30 percent increase."

And although he disputes specifics, Benepe still sees value in the New Yorkers for Parks' annual report card.

"Although we feel we are doing better than the report card would indicate, it's good to have an organization that fights for parks and for better standards," said Commissioner Benepe. "We don't take umbrage at the overall message, which is that parks should be getting better and better."

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Private Partnerships For Public Parks

Randall's Island

Last year, the city parks department and the Randall’s Island Sports Foundation worked out a deal to allow 20 private schools near-exclusive use of the island’s ball fields during after-school hours in exchange for contributing $85.5 million over 30 years to help upgrade and maintain the fields. In a city with a steep divide between rich and poor, the agreement seemed to hit a nerve.

Daily News columnist Juan Gonzalez summed up the outrage felt by many (including public officials representing the area) at the notion of privileged private school students locking up public fields during the hours when many schools run sports programs: “No one has explained why public parks, these natural treasures of our great city, are suddenly being converted into private airlines with first-class and coach sections.”

The deal illustrates the complications that can result from the reliance on private organizations to support what traditionally has been a public, taxpayer-funded service. The issue has been raised in park controversies around the city, from the inclusion of apartment buildings within the planned Brooklyn Bridge Park to City Hall’s refusal to allow protesters to gather on the lawn in Central Park.

"The prospective agreement at Randall’s Island is actually forcing all of us…to address the park dilemma straight on," said Christian DiPalermo, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks, the advocacy group. "Do we think parks are worthy of public investment so that they may provide universal access, or is it time to move to a model that requires some sacrifice in the universality of parkland in return for essential funding?”

A KEY SOURCE OF SUPPORT FOR THE PARKS

Central Park

In the 1970s, after city funding was slashed and the parks fell into disrepair, the Central Park Conservancy pioneered the concept of the private-public partnership to restore the landmark park. Many similar private-public partnerships were started, providing funding, grassroots energy, and innovative ideas to spark a citywide parks revival.

Last week, Bloomberg and the City Council agreed to put more permanent funding into the budget for parks. But the political reality in New York City is that the parks budget is among the first to be cut during times of fiscal crisis. Although the parks budget has held steady in recent years, public funding for operating the parks, once one percent of the city budget, remains just .04 percent. More than 20 large park partnership organizations and dozens of smaller ones help to fill the gap.

The Bloomberg administration has sought to build on and expand this private support. In addition to traditional philanthropy and private partners, it has encouraged corporate donations, concessions, the sale of naming rights, and funding mechanisms that link commercial development with the maintenance of public parks.

Even cities with generous parks budgets have embraced the concept of private groups to support the parks. “No matter how well funded a city’s parks are, they still need some help,” said Andy Wiley-Schwartz, vice president at Project for Public Spaces, a non-profit that works to improve community life through public spaces. “Having community stewards is priceless, and every city knows that, whether they fund parks or not. New York City also happens to need money.”

Private partners can be also more flexible and creative than city agencies that may be set in their ways and bound by union rules. For example, Central Park’s innovative zone management system, in which a gardener has responsibility for a specific section of the park, has proven very effective in keeping high maintenance standards and good community relations. Such groups can also provide a way for people to get more involved in their local park.

THE RANDALL’S DEAL

The Randall’s Island Sports Foundation was founded in 1992 by parents whose children played sports on the island and who wanted to realize the island’s potential as parkland. The group has raised private and public funding to restore and build new recreational facilities, including the $42 million Icahn track and field stadium, and run free summer and weekend programs for thousands of children in the neighboring communities of East Harlem and the South Bronx.

Under the proposed contract with the private schools, the island would get 65 new and restored fields. The schools would cover half of the debt service on the $70 million cost of constructing the new fields and pay for ongoing maintenance, but use the fields less than 15 percent of the total available hours. The Daily News recently reported that city officials plan to spend an extra $53 million on drainage and other infrastructure improvements as well. “The primary beneficiary of the project is the public,” said Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe, including the youth and adult sports leagues that play on the island on the weekends and in the summer.

The private schools have been busing students out to the island for years, claiming 95 percent of the fields after school. Their park department permits allow them to continue that use, whether or not the deal goes through. At present, there is not great competition for the fields after school because the island is difficult to get to by public transportation. But the school-age population of the adjacent neighborhoods is increasing, and if access is improved, demand for the fields will increase.

In addition to protesting restricted access to the fields, residents of East Harlem and the South Bronx say the Randall’s Island foundation hasn’t included their communities in planning for the island, has no local representatives on its board, and does not advertise events in their neighborhoods, keeping the island as an enclave for the wealthy.

At a recent City Council hearing on the proposed deal, board members of the Randall’s Island Sports Foundation acknowledged the board did not include representatives from those neighborhoods. But they stressed that the foundation’s goal was to provide a clean, safe place to play for all children. Karen Cohen, the group’s president and founder, said that it is working with 11,000 children from 100 local organizations. She said, “We want to make sure everyone is able to use Randall’s Island.”

OBJECTIONS TO PRIVATE FUNDING

The influence of private funding can extend to how a park is designed, renovated, and used.

A coalition of Brooklyn civic organizations and residents called Brooklyn Bridge Park Defense Fund, which is suing to stop the inclusion of luxury apartment buildings in the Brooklyn Bridge Park to subsidize its upkeep, says the planned towers would make the park into a playground for the residents, not a public park.

|

Washinton Square Park |

The original plan for the waterfront park, developed in a series of community workshops, included stores, a Chelsea Piers-like recreation center, and other uses that would bring people into the park. But when the final plan was released by the Empire State Development Corporation, which is overseeing the construction of the park, it contained luxury apartment buildings, a hotel, and office and retail space. The corporation said that when the actual economic analyses were done, the other commercial uses proved insufficient to generate enough revenue to support the park.

“The fear of privatization in any park is a reasonable fear,” said Marianna Koval, executive director of the Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy, which works to support the park. “It is important to strike the right balance. The housing will work to sustain 74 acres in perpetuity. That’s a great thing. Now, how do we protect against privatization from that housing, and across the board in this park?” Her organization is focusing on programming free activities and events in the park that establish “early patterns of use so that people feel welcome.”

A more subtle form of privatization can result when the financial investment by a private group or donor gives them a proprietary interest in a park. â€The city cedes authority, control, and responsibility to a new class of owner, who has rights and privileges because they are the ones who have to pay off the costs,” said Jonathan Greenberg, founder and coordinator of the Open Washington Square Park Coalition, which is fighting the park department’s redesign of Washington Square Park.

During the Republican National Convention in 2004, the city denied protesters’ request for a permit to rally in Central Park because it said the crowd would damage the carefully restored lawns. Protest organizers charged that the Central Park Conservancy’s interest in protecting the lawns it had paid to restore trumped the more basic right of public assembly.

Greenwich Village residents who are fighting the park department’s design for renovating Washington Square Park see the influence of New York University’s dollars in the redesign calling for a centered fountain and a fenced-in greensward instead of a more modest renovation of the vibrant but somewhat unruly existing space.

Parks Commissioner Benepe rejects that notion, however. “The issue that private dollars are driving the discussion in projects is somewhat of a red herring. It’s a substitute for the fact that some people just don’t like the decisions that are being made,” he said. “There are literally hundreds of projects at some stage of construction, design, and bidding. Unlike with most municipal projects, everybody has an opinion on it.”

FOLLOWING THE MONEY

Brooklyn Bridge Park (Illustration)

A reliance on private funding, observers say, lets the availability of money, instead of a more systematic assessment of park needs citywide, dictate which park projects will go forward. That can lead to prioritizing projects for affluent areas before meeting the needs of neighborhoods that don’t have private resources at their disposal.

There has been a lot of coverage in the press recently about a new playground near the South Street Seaport where children would use sand, water, and movable blocks to build giant constructions guided by adult “play workers.” Architect David Rockwell is designing this labor-intensive experiment at no charge and raising $2 million to pay for the staff. Meanwhile, the once ubiquitous “parkie” who kept playgrounds clean, unlocked the bathrooms, and kept an eye on children has gone the way of, if not the dinosaur, perhaps the panda. In 2005, the city funded 110 playground associates for the entire city during the summer months, two per City Council district.

The operations of the city’s private-public partnerships can also lack transparency and public accountability, advocates say. Even the extent of private support is not fully known, according to the Independent Budget Office. Between $60 and $70 million a year is provided to parks by partnership organizations, but that represents just part of the total. The budget office did an analysis of private funds spent on public parks at the request of the chair of the City Council parks committee, Helen Foster, but found that it could not give a full accounting because the necessary information was incomplete, out of date, or not publicly available.

In a letter to Councilmember Foster, budget office Director Ronnie Lowenstein wrote, “Since the city continues to rely on private funding for support of its parks and recreation programs, a more through annual accounting of private support would be beneficial in helping the City Council and others determine whether the total resources available for parks and recreation are sufficient and appropriately allocated.”

After the outcry on the Randall’s Island contract, city officials agreed to postpone the final vote by the city's Franchise and Concessions Review Committee and hold further discussions with all of the interested parties. Borough President Scott Stringer, Comptroller William Thompson, East Harlem Councilmember Melissa Mark Viverito and the local community boards have been negotiating to reach a compromise that would allow public school children and local residents to have greater access to the fields during after-school hours. The City Council's parks committee has scheduled another hearing on the issue for January 31. A vote by the franchise committee has been set for February 14.

However the Randall’s Island issue is resolved, the growing importance of private partners to the park system requires a closer look at the trade-offs involved.

“It’s the public sector’s responsibility to provide a framework, to define what it means to be a private partner providing a public service,” said Maura Lout, director of operations at New Yorkers for Parks. “We have to figure out a way to make this work, because we’re obviously going to see more and more of it.”

Editor’s Note: Rich Davis, chairman of the board of directors of Citizens Union Foundation(publisher of Gotham Gazette), is also chairman of the board of trustees of the Randall’s Island Sports Foundation.Dick Dadey, the executive director of Citizens Union Foundation, serves on the board of directors of the Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy.

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â