The Social Security Debate

You cannot go anywhere these days without hearing about Social Security. In the first two weeks of March, the New York Times ran more than 50 articles on it. President Bush barnstorms across the country promoting his ideas, while Democrats hold rallies to oppose them. People, such as New Yorker Beatrice Williams Rude, email their stories about Social Security to blogs. She told of her parents who, despite being knowledgeable investors, saw their savings dwindle in the 1980s. “But Social Security was there” and her parents “never stopped blessing FDR for Social Security: retirement with dignity.”

You cannot go anywhere these days without hearing about Social Security. In the first two weeks of March, the New York Times ran more than 50 articles on it. President Bush barnstorms across the country promoting his ideas, while Democrats hold rallies to oppose them. People, such as New Yorker Beatrice Williams Rude, email their stories about Social Security to blogs. She told of her parents who, despite being knowledgeable investors, saw their savings dwindle in the 1980s. “But Social Security was there” and her parents “never stopped blessing FDR for Social Security: retirement with dignity.”

And hundreds of New Yorkers – many of them decades from retirement – packed an auditorium at the New York Ethical Culture Society last week – to cheer, boo and whistle as experts debated the future of a program that, in one way or another, affects almost all Americans.

About 47 million Americans, including 673,000 New York City retirees, receive Social Security. Millions of New Yorkers and other Americans have Social Security taxes deducted from their paychecks and hope to collect benefits some day.

So it is not surprising that any effort to change the program would spark interest and strong emotions. To make the debate even more vehement, there is little common ground here. People disagree over what Social Security is – a pension fund or an insurance program to guarantee some degree of economic security for all. Americans argue over the proper role of government in insuring a decent retirement. They differ over the magnitude of the financial problems confronting Social Security. And they have bitter differences over the best approach to solving the problem – whatever the problem might be.

President Bush has declared Social Security to be in crisis and has made changing the system the focus of domestic policy in his second term. He has argued that the system will be “bankrupt” by 2042 and needs to be fixed “now once and for all.” Bush has pulled out all the stops in pushing for voluntary private accounts where people could put some of the money that goes into Social Security.

But -– and this indicates just how convoluted this whole debate has become -- even the White House admits private accounts will not solve Social Security’s financial problems.

Beyond the discussions of money, this is a political and ideological battle. Bush sees the private accounts as key to creating his “ownership society,” where patients control their health care, parents control their children's education, and workers control their retirement savings.

In a memo written earlier this year, Peter Wehner, a White House aide, called the debate about Social Security “a monumental clash of ideas.” “If we succeed in reforming Social Security, it will rank as one of the most significant conservative governing achievements ever,” he said, emphasizing, “we consider our Social Security reform not simply an economic challenge, but a moral goal and a moral good.”

Opponents see the Bush administration proposal as a dangerous effort to destroy the remaining vestiges of the New Deal and to weaken a program that has kept millions of senior citizens and others out of poverty.

“Our society has decided that everybody – the elderly, the disabled, orphans, and surviving spouses – is morally equal, and … deserves the peace of mind that is implied by the term â€social security,’” Dan Cantor of the New York Working Families Party wrote recently. “This is moral progress, and Bush is on the other side.”

Democrats and labor unions have launched an all-out attack on the private accounts. They have not, however, agreed on a proposal to solve whatever fiscal problems confront the system. Meanwhile, the public is left trying to sort it all out.

• HOW IT WORKS

• THE NEW YORK CONNECTION

• DEFINING THE PROBLEM

• PRIVATE ACCOUNTS

• THE SOLVENCY PROBLEM

• THE OTHER DEFICITS

• THE POLITICS

• A WALL STREET BOOM?

HOW IT WORKS

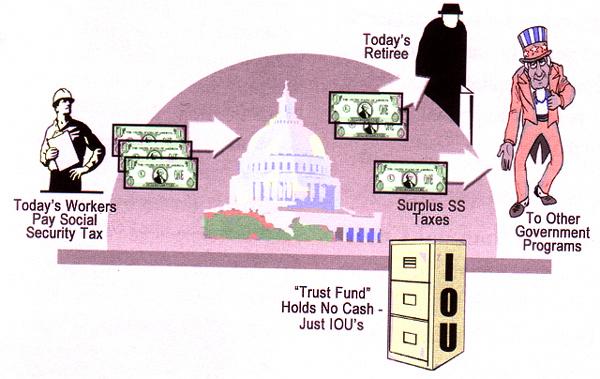

To finance Social Security, workers pay a tax of 6.2 percent on their earnings up to $90,0000. Their employers pay an equal amount. Though some people still think the money that workers pay in Social Security taxes today is squirreled away for them until they are ready to retire in the future, in fact the money collected today is spent today; it goes to make monthly payments to today’s beneficiaries. (Retirees of the future are supposed to be paid by Social Security taxes collected from workers of the future.) This is sometimes referred to as pay-as-you-go.

Most people receiving Social Security are retirees and their spouses, but benefits also go out to 7 million disabled workers and their dependents and 7 million survivors of deceased workers. In 2004, individual retirees received an average Social Security benefit of $922 a month, with married couples getting an average of $1,523.

Today's "Pay-As-You-Go" Social Security System

Illustration from Cato Institute's A Community Leader's Guide to Social Security Choice

For about two thirds of beneficiaries, Social Security provides at least 50 percent of their incomes. For about 20 percent, it accounts for virtually all their income. A new study by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities found that without Social Security, 44.4 percent of senior citizens in New York State would have incomes below the poverty line. With Social Security, the number drops to 8.4 percent, meaning that Social Security keeps almost 900,000 New Yorkers out of poverty.

The size of the monthly check depends upon how much money a person paid into the system, which, in turn, is based on how much the person earned and how long he or she worked.

A person who spent years at a high-paying job will get a larger check than someone who earned a low wage, but because the government intended that Social Security keep elderly and disabled people out of poverty, the less affluent get a higher rate of return on the money they put into Social Security than richer Americans. According to figures compiled by the Century Foundation, low-wage workers who retired at 65 in 2004 received Social Security checks equivalent to almost 85 percent of their wages; people who earned higher salaries saw only 45 percent of their wages replaced by Social Security.

And because the checks keep coming from retirement to death, people who live longer -- or whose spouses live longer -- do better with Social Security than those who die shortly after retiring. The government adjusts the benefits to keep pace with inflation.

Social Security operates through the federal budget, but the Social Security Trust Fund is a distinct entity. When there is a surplus –- when more money is coming in in payroll taxes than going out in benefits -– it is credited to the Social Security Trust Fund. The federal government borrows the money to pay for other programs and must then pay the Trust Fund back with interest. This year, for example, the money left over from Social Security reduced the current federal budget deficit by more than $170 billion. The federal debt held by the Trust Fund is currently about $1.8 trillion.

So even though Social Security’s revenue will fall short of benefits in 2018, Social Security can fill that gap with the money the federal government owes to the Trust Fund until 2042. It is then, when the Trust Fund is depleted, that the president says the Social Security system will be “bankrupt.”

THE NEW YORK CONNECTION

The idea for such a Social Security system came largely from three New Yorkers in the 1930s: President Franklin Roosevelt, Senator Robert Wagner, and Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, according to Maura Moynihan, daughter of the late New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Some 50 years later, Senator Moynihan, along with Republican Senator Robert Dole of Kansas, spearheaded the 1983 adjustments to Social Security that saved the system from imminent collapse by reducing some benefits, gradually increasing the retirement age from 65 to 67, hiking some taxes and delaying cost of living increases.

This year, Representative Charles Rangel of New York has emerged as a key opponent of the president’s plan because of his position as the senior Democrat on the House Ways and Means Committee, which will have to review any legislation on Social Security. And, when Democrats kicked off their offensive in the hottest domestic political fight of the year, they came to Pace University in New York City. New York Senator Hillary Clinton sponsored the rally where New York’s other senator, Charles Schumer, also spoke.

But not all New Yorkers agree with them. Some members of one of the city’s leading industries – the securities industry – hope the president’s plan for Social Security will pump more money into stocks and provide billions in fees for some investment firms.

DEFINING THE PROBLEM

To spur his proposed changes, the president has painted a frightening scenario for Social Security’s future. According to the White House, in 2018, the government will begin to pay out more in Social Security benefits than it collects in payroll taxes. Unless the government takes action, by 2027, the shortfall will reach $200 billion a year and, by 2042 –- when today’s 28-year-olds reach 65 -- the system will be bankrupt.

With birth rates down and the baby boom generation retiring, 21st century workers simply cannot keep up with the demand for benefits, the administration says. In 1950, each Social Security recipient was supported by the Social Security taxes collected from 16 workers. Today's Social Security recipient depends on only 3.3 workers.

“If we do not act to fix Social Security now, the only solutions will be dramatically higher taxes, massive new borrowing or sudden and severe cuts in Social Security benefits or other government programs,” the president has said.

But many of Bush’s critics dismiss such dire predictions. “The most successful safety net program in human history is currently sitting on $1.7 trillion in reserve funds and faces a possible shortfall decades from now, which minor corrections to the program could prevent,” wrote Robert Scheer in The Nation.

PRIVATE ACCOUNTS

The president has made private accounts the linchpin of his plan for Social Security.

Under this proposal, workers would eventually be able to take the 4 percent of their incomes that is subject to payroll taxes and put it in private accounts, instead of the Social Security. There might be a choice of funds, all run by professional money managers, that would put the money into some combination of stocks and bonds.

The plan would begin in 2009 with workers able to invest up to $1,000 in the private accounts. That would rise by about $100 a year until, after 26 years, it would reach its maximum –- $3,600 a year (in today’s dollars). Current retirees and workers aged 55 and over would not be affected.

Many details have yet to be determined, including how the funds would be managed, how many funds would be offered, and what if any the fees would be. The president’s plan does not set out a social safety net, though many of the bills proposed in Congress do. And it does not address how Social Security would handle benefits for people other than retirees -- for disabled workers or survivors of deceased workers.

The plan also presents daunting logistical challenges. “Any system that includes private accounts would require a massive effort to educate the public, enroll workers and answer what experts say could be hundreds of millions of questions,” Tom Lauricella wrote in the Wall Street Journal. “Computer systems to track contributions would have to be designed and built. Money would have to be collected and allocated. And the system would have to be policed for errors to ensure that workers get every penny they are due.”

For the next 45 to 55 years, private accounts could exacerbate Social Security’s fiscal problems. The money that working Americans put into private accounts will not be available to pay retirees’ benefits, since it will not go into the Trust Fund. That will require the government to borrow more money -- trillions some say -- to fill the gap.

Supporters of private accounts say that the government will have to spend huge amounts of money -- either in general funds or from government bonds -- on Social Security in any event. Paying the money to move to private accounts, argues the Heritage Foundation, would be more cost effective in the long run “than to continue to fund the system as it is currently designed.”

With private accounts, future Social Security benefit levels become unpredictable. The amount of money diverted to the private funds and the cost of borrowing money to fill the gap during the transition to personal accounts would reduce the size of the Trust Fund.

Then there is the biggest unknown: What return will people earn on their private accounts? Some have estimated that workers would have to get more than 3 percent (after inflation) to do better than they would do under the current system.

According to Paul Krugman, an economics professor at Princeton University and columnist for the New York Times, most privatization advocates assume over time a 7 percent return, after an inflation adjustment of 3 percent. In that case, retirees with private accounts would come out ahead.

Getting an account that makes financial sense is “not a slam dunk, but it ought to be attainable,” wrote Newsweek Wall Street editor Allan Sloan. But the accounts have other hitches, Sloan says. You would own them, but not control them (for example, you could not withdraw from them before retirement), and the money paid into these accounts would reduce the size of your conventional Social Security benefit.

|

Publications by an array of organizations stake out different sides in the heated debate over the future of Social Securit |

New York Senator Chuck Schumer has sought to dramatize the risk. His web site allows New Yorkers to compare their retirement benefits under the Bush plan with those under the current system (in inflation-adjusted 2005 dollars).

So, for example, a 40-year old with an average salary of $60,000 who would receive an annual benefit of $23,832 under the current system, and an annual benefit of $19,598 -- an 18 percent cut -- from the Bush plan. To make such calculations, Schumer assumes (In PDF Format) that the private accounts would get an annual return of 3 percent above inflation. A higher rate would produce additional benefits.

The debate over private accounts involves differing ideas of government’s proper role and of what Social Security is. Proponents of private accounts argue that individual Americans should have more control of their retirement funds and should be able to pass their unused retirement funds on to their heirs.

“Social Security turns us all into supplicants,” Michael Tanner of the Cato Institute said at the Ethical Culture Society debate. Private accounts, he said, would provide “a system in which middle and low income people can create a nest egg of real inheritable wealth....It’s about time we gave the doorman the same opportunity to invest as the person who lives in the duplex above.”

But that misses the purpose of Social Security, Krugman countered. “Social Security is not a pension fund, not an investment fund but a social insurance program,” he said

THE SOLVENCY PROBLEM

Whatever else private accounts may – or may not — do, they do not address Social Security’s fiscal health for much of the 21st century. "Personal accounts do not solve the issue," Bush said at his press conference last week.

A number of suggestions have been made about how to do that. They include:

--Limiting benefits for wealthy retirees: Currently a person’s overall wealth has nothing to do with the benefit he or she receives. Some people have suggested changing this, with the president indicating he would consider it.

--Other benefit cuts: Currently, Social Security benefits rise along with wages. Some experts have suggested that the increase instead be tied to rises in prices, which tend to go up more slowly than wages. This could reportedly take care of the solvency problem single-handedly but would also reduce benefits. According to calculations by Representative Anthony Weiner, this would gradually erode the size of benefit checks. The average 48-year-old New Yorker, who can now expect $940 a month, would get only $846. And younger workers would do worse: 18-year-old New Yorkers would see their benefits drop by a third – from an average of $940 to $640 a month.

--Increasing the retirement age: Senator Charles Hagel, an influential Republican and supporter of private accounts, has urged raising the retirement age from 67 to 68 in 2023, largely on the grounds that people live longer now than they did in the 1930s. Opponents of older retirement, such as the influential senior group AARP argue that such a move would disproportionately affect African-American workers, (in pdf format) who have lower life expectancies than whites. They also point out that just because people live longer does not mean they can work longer. Older workers may be unable to do physically demanding work and often face age discrimination that can prevent them from getting or keeping jobs.

--Raising the “wage cap”: Workers and employers only pay Social Security payroll taxes on the first $90,000 of earnings. This creates a maximum tax -- for the worker and employer -– of $5,580 a year. If the cap went up to $140,000, those making that much would have to shell out another $3,100 in payroll taxes. New Yorkers would be disproportionately affected by such a change since salaries tend to be higher here.

-- Increasing the payroll tax rate. A rise of only 7 percent -- from 6.2 percent to 6.65 percent for both employees and employers -- would allow Social Security to pay all its promised benefits at least until 2075, Robert McIntyre of Citizens for Tax Justice has written. But many supporters of lower taxes oppose hikes in either the payroll tax or in the wage cap.

--Investing revenues more profitably: Under federal law, Social Security can invest its funds only in securities issued or guaranteed by the federal government or guaranteed by the federal government. Some groups, such as AARP, have argued that a portion of Social Security funds could be invested more profitably.

THE OTHER DEFICITS

Some observers, notably Democrats, think the whole focus on the fiscal problems of Social Security is misguided at a time of massive federal deficits.

The White House has predicted that the deficit this year will rise to $427 billion. Some experts expect deficits could be far greater after Bush leaves office in 2009 because of tax cuts, the new Medicare prescription drug benefit and, if it passes, his proposal for private Social Security accounts. The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities predicts the Bush tax cuts and the Medicare prescription drug benefit will cost $19.2 trillion through 2078.

"Medicaid expenses in almost every state exceed that state's expenditure on public education: that is a crisis. Medicare has a life expectancy as a program of only about 15 years. So if you want to talk about real crises that the White House should be addressing, you'd start with those two programs,” Democratic Senator Richard Durbin of Illinois has said.

But Senator Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania, a Republican, said it makes sense to take on Social Security first – because it is so much easier to fix that than the health-care programs.

What is missing is a comprehensive plan to control the annual federal budget deficits. As another recent study (In PDF Format) has noted, deficit-reduction plans in 1990 (under a Republican president) and in 1993 (under a Democrat) raised taxes and cut spending. Both were key to the budget surpluses of the late 1990s. No similar move seems underway today.

THE POLITICS

So far, the public does not seem to buy the conservatives’ arguments for private accounts. A Washington Post-ABC News poll conducted earlier this month found that only 35 percent of those responding approved of Bush’s handling of Social Security, and 58 percent said that the more they heard of his proposal the less they liked it. Two-thirds of them, did, however agree with Bush that Social Security is headed for a crisis.

New Yorkers appear wary of private accounts, according to a poll (in pdf format) conducted last month by the School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University. Overall, 51 percent of New Yorkers oppose private accounts with 36 percent supporting the idea and the rest undecided. Among so-called Downstate New Yorkers – those living in New York City, Long Island and Westchester – results were more pronounced, with 54 percent opposing the private accounts and only 32 percent supporting them.

Most, if not all, state Democrats adamantly oppose the private accounts, and the one Republican member of New York City’s congressional delegation, Vito Fossella, has reserved judgment. “There are 100 moving parts to Social Security,” his aide, Craig Donner, told the New York Sun. “The White House said that personal accounts by themselves don’t ensure solvency. You have to see what the other 99 parts are before you an judge the plan.”

But even if Bush stumbles badly on this – Democrats fantasize that it could have the same devastating effect on congressional Republicans that the failed Clinton health plan had on congressional Democrats -- the Social Security debate presents hazards for Democrats. The party and many of its members have resisted presenting any solution of their own for Social Security’s problems. “To say there is no problem simply puts Democrats out of the conversation for the great majority of this country,” Democratic political strategists Stan Greenberg and James Carville have written. “Voters are looking for reform, change and new ideas, but Democrats seem stuck in concrete.”

A WALL STREET BOOM?

Regardless of what one thinks about the merits of the plan, if it passed, would it be good for New York? After all, the private accounts will be invested, and New York is the home to the nation’s financial industry. Increased business on Wall Street means more jobs, more salaries and bonuses for workers in the financial industry -- and more tax revenues for the city and the state.

University of Chicago economist Austan Goolsbee predicted(in pdf format) that fees on the accounts would bring Wall Street an additional $940 billion over the next 75 years, "the largest windfall gain in American financial history.” The Bush administration has disputed Goolsbee’s numbers, saying that the accounts would be managed by the federal government, avoiding such high fees.

And a report (in pdf format) by the Security Industry Association last year concluded that “ rather than a â€free lunch,’ Wall Street will realize only modest gains from these accounts.”

Even investment firms that see a big opportunity in the private accounts are soft peddling their support for them, afraid that their support would do more harm than good. "It could be wrongly used against advocates of reform, " Edward L. Yingling, incoming president of the American Bankers Association has said. And they worry about reprisals from unions, which adamantly oppose the accounts and could withdraw their huge pension funds from pro Bush firms.

But Tanner of the Cato Institute said that fees to Wall Street are not the issue. "The question is whether we're giving young workers more of a return [on investment] than they'll be getting today," he told the Washington Post.

For now, the dream of a Wall Street windfall has not swayed one influential New York billionaire and Republican. “I've never thought that privatizing Social Security made a lot of sense," Mayor Michael Bloomberg told reporters "I think what you'd see is that people would invest - some people would invest - unwisely....These are not monies that people should be speculating with."

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Organizations

AARP

The organization of older American opposes private accounts and cuts in benefits. Its web site includes information on Social Security

Cato Institute Project on Social Security Choice

The web site for the libertarian think tank that has been a major force in the push for private accounts.

Democracy for America

The organization, which grew out of Howard Dean’s unsuccessful presidential campaign, offers people the chance to read and submit stories about how Social Security has affected their lives.

Economic Policy Institute

A Guide to Social Security by a group that works to “promote a prosperous, fair, and sustainable economy.”

New Yorkers United to Protect Social Security

A campaign to urge Republican members of Congress from New York to oppose private accounts.

Social Security Choice

A project of the Club for Growth, this group advocate private accounts.

Social Security Online

The official web site of the federal Social Security Administration.

The Social Security Network

A project of the Century Foundation with arguments against private accounts, reports and links t9o news articles.

Strengthening Social Security

The official White House web site on Social Security

Articles

Bush's House Of Cards: The Privatization Fraud

Articles from American Prospect on Social Security and President Bush’s plan for private accounts.

Civic Elite Bets Social Security Loophole Loots

Some New Yorkers -- including four City Council members --already have private accounts.

American’s Senior Moment

Paul Krugman’s essay in the New York Review of Books looks at the demographic and fiscal problems facing Social Security and the country as a whole.

Q&A: The great Social Security debateÂ

WeCARE, For New Yorkers Still On Welfare And Unable To Work

More than half of the New Yorkers still on welfare are unable to work. Many have a medical condition, physical or mental; others have substance abuse problems. Another large group is too young or too old too work. A few are taking care of household members, or in some other situation temporarily preventing work.

The Human Resources Administration’s newest answer to this situation is WeCARE, an ambitious initiative intended to systematically address health and other issues. The administration expects to refer about 45,000 clients a year to several contractors offering employment services for people with disabilities.

Even critics of welfare reform welcome the city’s recognition that most current welfare beneficiaries face genuine barriers to work. A new source of vocational rehabilitation services and appropriate medical treatment could be just what many of them need to achieve financial independence.

However, the facts made public so far do not answer all the concerns of advocates for welfare recipients. The lack of answers may reflect holes in the plan for the new program.

What’s new about WeCARE?

The process will begin with a “biopsychosocial” assessment: a medical examination and tests, plus an interview about the client’s psychological and social history. This will put the client on one of four tracks: immediate work activities; immediate application for federal disability benefits; medical treatment for a current condition; or vocational rehabilitation.

This sounds very like the city’s PRIDE program, which ran from 1999 to 2004. It too attempted to redirect welfare recipients with disabilities into the workforce. In four and a half years, almost 37,000 participants were sent to PRIDE for assessment; of these, 5,800 found jobs and 3,100 were able to get federal disability benefits.

One difference will be that under WeCARE, a welfare applicant or client will be sent to a private contractor as soon as city workers learn of a possible barrier to employment. From then on, assessments, services, and case management will all be done by one contractor or its subcontractors. In the past, city workers retained many case management responsibilities for special-needs clients.

A larger difference, for people with disabilities, is that there will be new medical providers to evaluate and develop treatment plans for health conditions that can be stabilized. The clinic used for many years by the Human Resources Administration was considered by many clients to be too quick to dismiss their reports of disability, even when backed by medical records from personal physicians. As in the PRIDE program, beneficiaries will be required to undergo medical treatment. WeCARE staff will monitor whether they are carrying out their treatment plan.

Other than that, there are few new elements in the WeCARE program. In recent years, the city has screened welfare applicants for disabilities, substance abuse problems, literacy needs, English language skill deficits, and domestic violence; and staff have been expected to refer clients to appropriate services as needed. Those who reported having disabilities were sent to a clinic for medical and psychological examinations. Those who could work were sent to outside contractors for “skill assessment and placement” and, if necessary, for employment preparation and training.

The challenge of screening to find candidates for WeCARE

It is not clear how the Human Resources Administration will decide whom to refer to the WeCARE program. Effective screening for disability requires interviewers to explain the benefits of disclosing a condition: additional medical treatment and vocational services, the possibility of finding a job that is modified to fit their condition, and protection against discrimination.

Patience, respect for clients, and encouraging applicants to seek more services have not been the hallmark of welfare reform in New York City in the past. Under the PRIDE program, the city relied on welfare applicants to report their own physical or mental disabilities to job center employees.

This is likely to have excluded a number of applicants aware of having a condition that interfered with work, but not aware that their condition qualified as a disability, entitling them to accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act. People with arthritis or back pain may not know of any accommodations that could enable them to work without severe pain. Those with lupus or sickle cell anemia may have to take so many sick days that they cannot hold a job. Diabetics may need a workplace where they can store medication in a refrigerated space, and eat at specific times.

Still other people, on or off the welfare rolls, do not recognize the existence of a disability that interferes with their ability to work. Mental illness, for instance, can make it extremely difficult to look for a job, pursue vocational training, and/or navigate the Human Resources Administration’s procedures. However, the stigma associated with mental illness contributes to a widespread reluctance to face it.

One person can have multiple barriers to employment. Substance abuse or domestic violence might be the first ones identified. If the client does not trust a service provider, and the provider is not looking for the full picture, underlying physical or mental illness could go untreated, making other interventions useless.

Privacy issues in medical assessments

The WeCARE process puts its biopsychosocial assessment first, before the vocational assessment, and that raises privacy issues. Unless a client claims to have a disability that will interfere with work activities, welfare workers cannot assume that a visible disability is a barrier to work. An applicant cannot be ordered to submit to medical tests and questions about her psychological history as a condition of receiving welfare benefits.

Nobody is legally required to tell a WeCARE intake worker that they have a disability. According to the state’s Department of Labor, welfare applicants and beneficiaries cannot be forced to undergo medical assessment and treatment unless the government has “reasonable cause” to think that the client’s disability will prevent him or her from working. The Department of Labor suggests (In PDF Format) that a documented history of failure at work activities is required before medical examinations and treatment can be made a condition of receiving benefits.

However, waiting for failure at work activities is expensive for the city and discouraging for clients. It can lead to people churning through the welfare system without getting the help they need. Welfare recipients who lose benefits because they are sanctioned are more likely than other recipients to have major barriers to work, according to the Manpower Demonstration and Research Corporation. The Corporation recommends a combination of treatment and work support, such as that offered by WeCARE, cautioning that clients must be monitored on a long-term basis, to prevent deterioration during relapses or life crisis.

Who will train the job trainers?

The two contractors who will provide the bulk of WeCARE services are Federation Employment and Guidance Services (for Manhattan, Bronx, and Staten Island), and Arbor Education and Training (for Queens and Brooklyn). Both have experience in providing employment services under New York City contracts.

However, neither seems to be trying to staff the new program with workers with disabilities who could serve as role models for clients. Disability awareness is not a concept easily understood by those without disabilities. Without personal or work experience, workers may reduce complex situations to stereotypes, and apply a short list of cookie-cutter solutions to all problems.

The staffing plans of the two agencies, as shown in job descriptions posted on the Internet, require some managers to have education or experience in working with people with disabilities. However, no such requirements are listed for the frontline staff who will deal directly with clients.

Arbor plans to hire “intake specialists” to conduct the “psychosocial assessment” of new clients. Intake specialists may be hired with no education beyond high school, although they will be responsible for interviewing clients and writing summaries of their medical, psychological and social histories. Presumably, this report will play a large part in determining the path each client follows through Arbor’s system.

Medical compliance may be a stumbling block

The medical component of WeCARE is the Wellness/Rehabilitation Plan through which clients are meant to improve their health enough to be able to work. WeCARE will refer clients to appropriate providers, provide case management and health education, and monitor how well clients comply with doctors’ instructions.

It is not clear whether WeCARE case managers will be responsible for filing reports that lead to their clients’ loss of benefits. WeCARE staff are also supposed to help clients comply with treatment plans, and they can do this most effectively if clients trust and understand them.

WeCARE must expect that its clients, like other patients, will often fail to follow doctors’ instructions. Researchers estimate that when prescriptions are given to Americans with chronic diseases that have recognizable symptoms, patients take the medicine as directed only 60 to 70 percent of the time. Even medical professionals take medication incorrectly twenty percent of the time.

WeCARE meets Federal welfare reform reauthorization

After years of postponing it, Congress appears ready to address reauthorization of the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program, which governed the process of welfare reform. Hardliners want to make more welfare beneficiaries go to work, even though the people still on the rolls are those least able to get and hold jobs. The current law requires states to have half of their cases involved in “work activities.” The bill under consideration in the House of Representatives would raise the requirement to 70 percent of cases.

As of February 2005, 36 percent of the city’s Family Assistance recipients were working. The workweek now required is part-time; proposals to make it full-time threaten to prevent welfare recipients from taking part in valuable activities that don’t count toward the federal definition of “work.” For people with disabilities, sometimes the most essential job accommodation is a part-time schedule.

The city has already testified before Congress that raising work participation requirements will increase the need for federal funding of work supports. Higher requirements might also undermine WeCARE’s efforts to build on recent experience in welfare reform.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits.

The Working Poor

Last year, about one in three low-wage full-time workers in this city experienced one or more of these hardships:

- their gas, phone, or electricity was turned off because they couldn’t pay the bills;

- they used a food bank or pantry to avoid going hungry;

- they couldn’t pay the rent;

- or a prescription cost too much for them to fill it.

In The Unheard Third: Bringing the Voices of Low-Income New Yorkers to the Policy Debate, the Community Service Society and the United Way of New York City document the street-level effects of New York’s inadequate minimum wage of $5.15 per hour. Many of the working poor saw their wages or tips go down last year, had their hours cut back, or lost their jobs entirely. Statewide, over 88 percent of families supported by low-wage workers are headed by at least one adult over the age of 25; the minimum wage is not limited to teenage workers.

Those earning the least also receive the fewest employment benefits, which are taken for granted by higher-paid workers. Nearly two-thirds of low-wage workers reported having no paid vacation days or sick days. Almost half had no health coverage, with the majority lacking prescription coverage for themselves and/or health coverage for family members. The working poor have no need of financial advisors: Only one-third are offered a pension or 401(k) retirement plan, and most have less than $500 in savings.

There is little margin for emergency needs here. A parent who misses work to care for a sick child loses money every day and risks being fired. A few extra dollars a month for subway fare, or a four percent rent increase, means the family must do without another essential item.

Food Stamps Are Back in Favor

Under the Giuliani administration, food stamps were considered a form of welfare, and the city sought to “wean” working recipients from them. The Bloomberg administration has indicated more willingness to extend food benefits.

The city’s Human Resources Administration is collaborating with a food stamp outreach initiative of the Community Food Resource Center, with participation by Pathmark Supermarkets. The center will post advocates at supermarkets to educate shoppers about food stamps, screen them for eligibility, and help them fill out applications.

Little Help from Education and Job Training

While federal job training programs have a good record of helping graduates find and keep jobs, they are not reaching those New Yorkers who need them most. Statewide, less than one-third of 1% of adult high-school dropouts complete job training programs.

The city’s Local Law 23 mandated access to job training and education for welfare recipients, but the Bloomberg administration has not implemented the law, nor has it complied with a 2003 court order to provide a list of approved training programs to welfare recipients interested in enrolling. Nearly 80% of welfare recipients didn’t know that there were educational programs open to them, according to a survey by the Urban Justice Center and Families United for Racial and Economic Justice. For every two respondents who attended school last year, another seven were interested in doing so, but did not.

One unemployed woman had enrolled full-time in college before becoming eligible for welfare. She reported that a welfare worker told her that she would have to give up school in order to meet the work requirement. This was a direct violation of the city’s obligation to make a reasonable effort to accommodate the class schedule of a recipient enrolled in school.

Over 300 welfare beneficiaries were surveyed for the report, at ten of the city’s Job Centers. Such a survey would be more difficult today, now that an appeals court has upheld the city’s ban on the presence of advocates in job centers, unless they are on “official business,” as defined by the Human Resources Administration. [See “A Ban On Welfare Advocates At Welfare Centers,” by Emily Jane Goodman, Gotham Gazette, September, 2004.]

Better Days Are Not Ahead for the Working Poor

Currently, the working poor have limited opportunities to climb out of poverty, according to Between Hope and Hard Times: New York’s Working Families In Economic Distress (In PDF Format) , by the Center for an Urban Future and the Schuyler Center for Analysis and Advocacy.

The authors found that even before the recent recession, median household income dropped in all four outer boroughs during the 1990s. While the United States as a whole saw a slight drop -- 1.3 percent -- in the number of low-income households during that decade, New York State had an increase of 2.7 percent in its number of low-income households.

The hardships faced by low-income households are increased by New York City being one of the two most expensive places to live in the country. The cost for just three commodities—education, housing, and child care—illustrates the difficulty of working your way out of poverty.

A community college degree adds an average of $7,000 to a worker’s annual income, but tuition increases keep moving education further out of reach. New York City community colleges raised tuition to $2,800 a year in 2003. Students who work and go to school part-time aren’t eligible for the major source of financial aid: the Tuition Assistance Program.

Planned Shrinkage of Housing for the Poor

New York City’s permanent housing emergency continues to grow worse. Large new public housing projects are no longer being built. Poor tenants have come to increasing rely on Section 8, a federal program of vouchers that pay part of the rent, but there is a long waiting list for the program, and a likelihood that its funding will be cut next year. (See Affordable Housing in 2004 by Joe Lamport)

Inadequate Child Care

The city provides child care subsidies for 105,000 children; it is estimated that another 100,000 are eligible, but not receiving a subsidy. Low-income parents usually turn to unregulated care, such as leaving children with a relative or neighbor. Even among families using subsidized day care, 38,000 children are in unregulated care. Unregulated settings rarely offer the learning activities provided in more formal child care settings, so children entering school from unregulated day care start out with a disadvantage.

Work Supports as a Subsidy to Employers

Housing vouchers, child care subsidies, food stamps, and publicly funded health coverage can be seen as subsidies that benefit employers by allowing them to hire workers at salaries too low to live on. If government chooses to use tax dollars to help employers, there should be some criteria for this assistance. Perhaps businesses could be required to pay a living wage, with essential fringe benefits, unless they passed a means test based on their profit margin or on the salary of the highest-paid executive.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits.Â