Court Finds City Isn't Obligated to Continue Housing Program

When a group of battered women and homeless individuals and families, agreed to leave public shelters and become tenants of private but rent subsidized apartments offered by the City of New York, they expected to occupy them for one to two years. The City was to pay all or a portion of each unit’s rent for one year and renew for a second year if the occupant met the eligibility requirements for the Advantage Program, including that they fulfilled public assistance requirements and worked 20 hours a week at minimum wage jobs. However, the Program ended soon after it began when federal and state funds were cut off. And the formerly homeless and victimized faced homelessness and violence once more.

A lawsuit against the City of New York sought continuation of the Advantage Program. But trial judge Judith Gische dismissed the case, finding that there was no contractual promise to provide the apartments. Last month that decision, known as Jasmine Zheng v The City of New York, was upheld by the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court in Manhattan. Saying, "We sympathize with plaintiffs and realize that an adverse outcome places them at risk of again ending up in the New York City emergency shelters… ," the four judges agreed that "defendants [City] are not contractually obligated to continue making rent subsidy payments under the Advantage Program."

What was the relationship between the shelter occupants and the City when the moves from shelter to individual apartments took place? "Simply social services," said the judges. With one judge dissenting, the Court held that making apartments available to people who gave up their places in homeless shelters was "simply social services and the defendants did not intend to be bound contractually."

An Opinion by four of the five judges who heard the appeal, held that "the existence of a binding contract is not dependent on the subjective intent of the parties, but on the objective manifestations of intent." The City argued, and the Court accepted, that the signatures on City-prepared documents were only to "ensure that the participants were aware of the terms of the program." In other words, the signatures on a document and the use of such words as "agree" and "guarantee" did not mean it was an agreement or a contract, and the tenants simply did not understand that it was within the City’s discretion to terminate; there was, the judges ruled, no "meeting of the minds," an essential element of a contract.

Since there was no contract, there was no obligation to continue the rent subsidy. The Court rejected tenants’ argument that they gave up something – places in shelters – for the subsidized housing, seeming to say they would have had to do that whenever so directed by the City, anyway (despite the obligation to provide housing accomodations), meaning that they really gave up nothing. The plaintiffs’ argument that they were induced to leave the shelters to move into into apartments they could not afford without the subsidy, was also found to be "without merit.

While four judges concurred, only Justice Karla Moskowitz dissented, finding that the plaintiffs were induced to leave the "relative safety of the shelter system and to enter into leases for apartments they could not afford [without public subsidies]." She found that there were enforceable contracts under which the "city agreed to pay plaintiffs’ rent in return for plaintiffs leaving the shelter system." The rent payable to the landlord was, according to Justice Moskowitz, a commitment not only to the residents, but also to the private landlords the city would be paying on their behalf. Analyzing the legal elements of a contract, she found that the agreements were, in fact, binding contracts even if they were also part of a "social benefit program." In addition, she said that the written documents prepared by the City and signed by the plaintiffs, described itself as an "agreement." The participants then signed leases with private landlords with the City paying the Advantage portion directly to the landlord. The agreements stated that the City was paying the rent in return for the plaintiffs leaving the shelters and said, the "Advantage program guarantees that the subsidy portion of the rent will be paid ..." The conditions that the participants remain eligible was never breached by them and the only condition for continuing the program into the second year was that on-going eligibility. Most telling for the dissent was that the City never conditioned the program on the continuation of state or federal funds and that the City concedes that it is less costly to fund the Advantage Program than to house plaintiffs in shelters, and that continuation would not only mean honoring a contract, but would save the City $133million.

Disagreeing with her colleagues, Justice Moskowitz describes their Opinion as a "red herring," and "buying into" the argument that "plaintiffs had a legal obligation to seek housing anyway." But, she argues, they had "no preexisting obligation to move into apartments they could not afford on their own. Nor did plaintiffs have an obligation to place themselves in a worse situation than they were [in] before." This left them legally bound to leases they "could not afford on their own." Parsing the language of the documents, the dissent refers to the City’s chosen words: guarantees, shall pay, will pay, assures, commitment as demonstrating "an intent to bind oneself contractually."

Seeking apartments for themselves at the beginning of the process, the would-be tenants had to show private landlords the documents prepared by the City and the landlords undertook the leases containing language that "the City ... will pay directly to me, the Landlord, monthly rent .. .’" These the dissent said, constitute a clear "assent to guarantee rent payment....." Judge Moskowitz said that the trial judge who dismissed the case was incorrect in finding that the landlords did not manifest assent when, they agreed to accept the tenants, and to continue the tenancies for a second year based on the City’s determination of eligibility, and agreed not to raise tenants’ rents, and forego other property rights in exchange for guaranteed rental payments for one to two years. This, Justice Moskowitz calls, "a textbook example of mutual assent." Also, the landlords would be unable to collect rent from tenants who never had the ability to pay the rent on their own, and would have the burden and expense of undertaking eviction proceedings which they never bargained for in dealing with the City. With the majority upholding the Gische decision, the tenants would be left with apartments they could not afford on their own, and the prospect of homelessness. Those who were victims of domestic violence, would lose not only their places in shelters, but also the protections against their abusers. "...they may be forced to return to the dangerous homes they sought to escape in the first place. Some may simply take to the streets," concluded the one judge who would have upheld the agreement as a binding contract

The judges in the majority were Justices Gonzalez, Sweeny, Renwick, Richter.

In addition to the actual parties, amicus curiae (friends of the Court) briefs were filed by Sanctuary for Families, New Destiny Housing Corporation, Center Against Domestic Violence, Safe Horizon, Violence Intervention Program, In., New York Asian Women’s Center, Good Shepherd Services, Barrier Free Living and Homeless Services United.

The plaintiffs were represented by The Legal Aid Society and Weil Gotshal and Manges LLP.The City of New York was represented by Corporation Counsel. The Amicii were represented by Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, LLP.

Emily Jane Goodman is counsel to Siegel Teitelbaum & Evans, LLP

Council Acts on Foreclosures

First your heat is turned off. Then the leaks start. Mold is growing and harmful lead paint begins to peel. Countless calls to the landlord go unreturned, because the management stopped paying bills months ago — the building is facing foreclosure and soon, an even-more anonymous bank will own the building.

With hundreds of residential building facing foreclosures each year, these conditions are not uncommon; they are also exactly what a new City Council bill hopes to prevent.

The bill, 501-A, will require banks to notify the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) fifteen days before a foreclosure action is taken on a residential building. This will allow the HPD to help keep buildings up to code and ensure the building’s sale to new, responsible buyers.

The bill will press banks to take more responsibility for the fact that the assets they seize still have tenants living in them, Quinn said; “you lent the money, you own the building.”

Keeping the Roaches Out

In addition to deteriorating physical conditions, distressed buildings are particularly susceptible to corrupt buyers and illegal conversions (as buyers convert units to boarding houses to raise cash fast).

With a nod to the New York Daily News investigation that found limited city efforts to crack down on illegal conversions, Council Speaker Christine Quinn said she hopes the new bill will prevent those conversions from ever happening by allowing the HPD to work with banks to vet out corrupt buyers from buying distressed properties from the banks.

“Slum lords exist on the belief that no one is watching,” Quinn said yesterday. “They’re a little bit like roaches, when the microscope is on them they run away.”

The bill will require the HPD to update their website quarterly with the number of foreclosure actions that exist in each community district. For buildings with twenty or more units, the HPD must list basic building information on the site so tenants and neighbors can be informed of foreclosure activities. This data will also help city officials to monitor struggling areas.

The bill is the latest passed legislation that Quinn proposed in her 2011 State of the City address, coming just two weeks after the Fair Parking Legislative Package, which was a major goal of last year’s speech. Quinn’s State of the City for 2012 is scheduled for next week.

Contract Transparency

Another promise from the 2011 address was to more aggressively monitor city contracting; following on December’s Outsourcing Accountability Act, the Council passed a Contract Transparency Bill today, which requires the city to create an online database of the cities 15,000 contracts (which costs the city $10 billion a year) with information on the money spent, the contractors, and the contract details in plain English.

This bill aims to combat costly confusions, like the one that occurred over whether the city or a contractor was supposed to shovel the snow around bus shelters. Councilman Domenic Recchia, Jr. read one 1500-page contract only to find that an outside company was contractually obligated to remove the snow around bus shelters — something the Sanitation Department was spending hundreds of thousands of dollars to do.

“Faced with the current fiscal reality and a ballooning contract budget, it’s imperative to know how each and every City dollar is spent,” Quinn said. “That way, both the Council and the public can see exactly where our money is going and where we can cut back.”

The database will be partially available on July 1st 2012 and fully completed by the same date in 2013.

Politics Thwart Brooklyn Housing

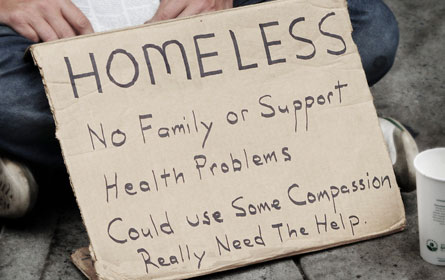

Homelessness is at a record-breaking high in New York City, and affordable housing remains scarce. In the case of one housing development project in Brooklyn, political and religious rivalries only add to the problem.

On Jan. 4, 2011, Justice Emily Goodman issued a preliminary injunction barring New York City from moving forward with the affordable housing project.

The Broadway Triangle project, which was approved by Mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2009, promised the development of 1,800 new housing units located in Brooklyn—44 percent of them for the poor.

But the ongoing lawsuit over the project raises questions over whom, exactly, the plan will benefit. The battle pits multiple organizations from the black and Hispanic communities against the mayor, and rival branches of the Hasidic Jewish community against each other, all of which are fighting for the same ultimate goal: more housing.

According to reports released by the Coalition for the Homeless in November, there are currently over 10,000 homeless families in New York City. And, “at the end of October there were 41,204 homeless adults and children sleeping in New York City municipal shelters, an all-time record.”

And a census bureau report stated that between 2005 and 2009, 18.6 percent of New York City residents were living in poverty, compared with 15.1 percent nationwide.

The report also stated that between 2009 and 2010, the poverty rate increased for non-Hispanic whites, for Blacks, and for Hispanics.

In spite of a general need for affordable housing, the lawsuit complicates the issue.

The Complaint

The Broadway Triangle Community Coalition (BTCC), a group of 40 Brooklyn-based organizations filed the suit two years ago, alleging that Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Raphael Cestero, commissioner of New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, discriminated against the Latino and African-American communities, and in favor of the Hasidim.

Political schisms and a federal investigation of one of the organizations involved in the project, the Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Citizens Council, have brought development to a halt, while thousands of low-income families still require affordable housing.

The BTCC sees this project as targeting a population unrepresentative of those in need. In a no-bid process, the city delegated the project to the United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg, Inc. (UJO) a Hasidic community group directed by Rabbi David Niederman, and the Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Citizens Council, an organization founded by New York State Assemblyman Vito Lopez.

According to New York State Supreme Court records, the plaintiffs alleged, “Hasidim are significantly over-represented in the three Williamsburg developments in that white families, who constitute 10 percent of the Housing Authority’s applicant pool, constitute approximately half of the families.”

“UJO pushed for the rezoning of the Broadway Triangle â€exclusively for its own uses,’” the plaintiffs stated.

Specifically, they cited UJO’s plan to create six-or-seven story buildings with very large apartments as catering to the Hasidic community. Lower buildings are more convenient for the Hasidim, who do not use elevators on the Sabbath, and larger apartments would suit their typically larger families.

In the petition and complaint, the BTCC stated that “the City’s rezoning only for 6 or 7-story low density buildings is an intentional and unjustified limitation on the number of others, namely non-white families, who would otherwise be able to live there and who currently make up more than 90 percent of the borough-wide waiting list for affordable housing, particularly for 1 to 2 bedroom apartments.”

Gabriel Taussig of the NYC Law Department issued a public statement on Wednesday calling the plaintiffs’ claims “outlandish,” stating that they had “no merit.”

The Conflict

Of the 40 community groups in the BTCC, 38 represent Latino and African-American communities in Brooklyn, which have felt friction with the Hasidim over housing for decades.

However, the remaining two organizations, United Jewish Community Advocacy Relations and Enrichment (UJCARE) and Central Jewish Council are in fact, members of the Hasidim.

Why are these two Hasidic groups aligning themselves with a coalition fighting against the Hasidim? Gary Schlesinger, the CEO of UJCARE, blames the UJO. Schlesinger believes that not enough of the Hasidic population is being supported by current housing developments, many of which were also overseen by the UJO. “Schaeffer Landing had 150 units. Only 29 Jewish families moved in,” he said.

In response to UJCARE’s participation in the lawsuit, Rabbi David Niederman of UJO said, “On the one hand they’re saying that there are too many Jews, and on the other they’re saying that there are too few Jews. Explain to me that logic.”

Whatever the logic, there is a reason.

The rivalry between the UJO and UJCARE is rooted in a feud over rabbinical legacy five years ago that ruptured the Williamsburg Hasidim.

When Grand Rebbe Moses Teitelbaum, the leader of the Satmar Hasidim for 27 years, died in April 2006, it was still unclear who would succeed him. Though traditionally a rebbe selects his successor in his lifetime, the case of the Teitelbaum brothers was more complicated.

Sam Beck, a Cornell University professor of human ecology in an unpublished draft of his recent essay, “Satmar Hasidim in Williamsburg” writes, “It did not take long for [Moses’s] sons, Aaron, the eldest, and Zalman, the younger, to start fighting over who was going to take over the reigns of the community and the Satmar rabbinical title.”

The repercussions of that feud are still felt today. In the BTCC’s petition and complaint, UJCARE describes itself as a “not for profit corporation dedicated to representing the interests of the Hasidic Jewish community, the majority of whom, among others, the UJO has abandoned because they support and/or are associated with the followers of the Satmar Rebbe Aaron Teitelbaum.”

But Niederman claims that the UJO serves all of the 70,000 members of the Williamsburg community, which represents over half of the Satmar Hasidim nationwide. “The UJO represents each and every one in the community,” Niederman said. “On a personal level, I belong to the Zalman synagogue. I continue to pray there but I work very closely with the institutions that belong to Rabbi Aaron.”

However, in December 2009, the UJO vigorously opposed the Rose Plaza, a housing development project proposed by a UJCARE affiliated developer.

In 2008, WNYC radio reported that UJCARE had received $200,000 in funding from the city council for the new fiscal year, a move that angered the UJO, which had received $210,000, a drop of 30 percent from the previous year.

The antagonism between these two community organizations has not only affected the housing development projects in Brooklyn, but also holds broader political implications.

Historically, the Hasidic population has represented a valuable cache of political influence, according to Hasia Diner, a professor of American Jewish history at New York University. She explained that because the Hasidic community was so firmly united, in the past they could ensure 100 percent of the vote.

Schlesinger is aware of this political clout but talks about how it has changed. He says that since the split, “The UJO can’t guarantee the entire vote anymore. Politicians know—you can’t fool them twice.”

That is the case of Broadway Triangle Community Coalition v. Bloomberg. Part of the Hasidim, which formerly showed strong support for Bloomberg, is now engaged in a legal battle against him.

On the other side are UJO and Vito Lopez, a powerful ally of the UJO, who is at the center of federal investigations revolving around accusations of fraud at the Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Citizens Council and related nonprofits.

Lopez’s Chief of Staff, Leah Hebert declined to comment on these allegations.

Pending these investigations, Justice Emily Goodman had suspended proceedings on the case over the Broadway Triangle development project.

Left Out

Perhaps the most affected are those families who are in need of affordable housing but instead find themselves the incidental victims of politics.

Dana Donaldson, a 27-year old single mother of two with another baby on the way was the victim of domestic violence. She says she’s been living in shelters for the past 14 months.

She talked about the lengthy process of finding housing. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development, which assigns housing by a lottery-based system, can take years.

“Housing takes three years,” said Donaldson. “I wanted to be out of here at least before I had the baby. No one wants to have a newborn inside of a shelter.”

“If you don’t want to sit back and wait for housing, you need a job for your own place,” she said. Nelson does occasional work as a hair-stylist but says it’s nearly impossible to find work since she’s expecting her baby within the month.

“I go to people’s houses and do their hair even though I’m not supposed to be,” she said. “Anything I’ve got to do, I’ll do it for my kids but it’s hard.”

Gloria Nelson, 39, has been homeless since November 2009 and now resides in the Salvation Army Bushwick Corps shelter. She takes care of her husband, who suffers from diabetes, and her two small children.

She said it’s difficult for her to imagine a future for her children. “It gets to the point where you do whatever you have to do,” she said.

She also described the difficulty of the lottery process. “We submit applications, applications, applications. You got to keep doing it until something comes up.”

Juliet Morris of the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development estimates that over 90,000 applications for apartment housing lotteries are received per year. “It is clear that there is a critical need for affordable housing in New York, and it is a need that our mayor has prioritized during his administration,” she said.

Morris declined to comment on the Broadway Triangle project.

“Everything is politics but the only ones feeling it is the ones at the end of the totem pole,” Nelson said. “My biggest hope is getting a place for me and my family. I just need to get my kids out of that whole system.”