Without Health Insurance

A woman from Pastor Ebenezer Martinez’s church was recently bit by a dog, and ended up spending a week in the hospital. Neither the woman nor her husband had health insurance, and they were worried about the thousands of dollars of medical bills. Martinez is not sure how to help her, or the many others among his South Bronx congregation he knows don’t have insurance. But he does know what they’re going through: He is not covered, either.

Martinez, 54, gave up what he refers to as his “secular job” as a counselor at the Upper Manhattan Mental Health Center two years ago, when he left to become the pastor at the First Pentecostal Church of Jerome Avenue as its only full-time employee. Knowing that the church was not in great financial shape, he hid his medical condition –- he has high blood pressure -– from the board of trustees, so it wouldn’t strain to pay for health insurance. Martinez gave up his prescription drugs, instead taking aspirin when he felt pain in his chest or arms.

“Using aspirin is not the same, but you know, aspirin helps a little,” he said. The prescription "was very expensive.”

Aspirin was not helping enough, however, and Martinez ended up in the emergency room for nosebleeds he couldn’t control. The trip cost him $700, and he still left without a prescription.

Stories like Martinez's are common in New York, where almost a quarter of the population lacks health insurance. True, the percentage of New Yorkers without insurance has been dropping in recent years, largely due to a unique statewide program that allows community groups to sign New York residents up for Medicaid. But health care advocates fear that within a few months this program will end, and the gains that have been made will be reversed.

Public officials are aware of the growing anxiety among New Yorkers. Mayor Michael Bloomberg made a campaign promise that within the next four years virtually every child in the city would have health coverage. The mayor and the city council are also pushing separate efforts to encourage – or force – private employers to give their workers health insurance.

But as it stands today, huge problems remain. People of color are much more likely to be uninsured than whites, aggravating racial disparities in health care. And experts and officials worry that having a large uninsured population is undermining the financial stability of the health care system as a whole.

“From a health care system’s point of view, the uninsured are the single largest structural flaw in the system,” said James Tallon of the United Hospital Fund.

On an individual level, the lack of having health insurance is often devastating financially. Other times it is far worse. Manny Lanza learned that he had a serious brain condition, AVM, after he had a seizure in 2004, and was referred to St Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital for treatment. But for months, the Manhattan hospital reportedly refused to provide care for him until he had insurance. His family labored to get him enrolled in Medicaid, but the delay, they charge, was deadly: Lanza died in his bedroom earlier this year. He was 24 years old. After his death, according to the Post, debt collectors for St. Luke's-Roosevelt called the family demanding payment of $42,000.

THE COSTS OF BEING UNINSURED

About half of New York City residents get health insurance through their work, either receiving it as a benefit free of charge or splitting the cost with their employer. Another quarter of the population receives health insurance through a public health plan like Medicaid or Medicare. Funded by various levels of government, these programs are available to the elderly, the poor, and other disadvantaged populations.

But 1.7 million New Yorkers have no insurance at all. Most, like Martinez, are adults working for small employers, the majority at secular jobs like restaurants or hardware stores. Eighty percent of city residents without insurance are either employed or are the dependents of someone who works.

“There are programs for the very poor,” said Martinez. “But people like me are in between.”

People without insurance are less likely to get preventive care. They often wait until their health problems are too serious to tolerate or ignore, and then arrive at hospital emergency rooms. By this time, health problems that could have been easily addressed earlier have become difficult or impossible to treat.

While it is less effective, the health care received by the uninsured is actually more expensive, both for the patient receiving it and the health care system providing it. Because uninsured patients do not have access to the group discounts that insurance companies negotiate for their clients, they pay higher rates, a burden that has become ever less bearable as health care costs skyrocket. Unpaid medical bills are now the country’s most common cause of personal bankruptcy.

Treating uninsured patients also takes its toll on the hospitals that do so. Dealing with a problem once it has progressed to the point that it warrants an emergency room visit is much more expensive than preventive care; and if a patient cannot pay for this visit the hospital is left to pick up the bill. This burden falls particularly hard on the city’s public hospitals, and is regularly cited as a reason for their financial difficulties.

No one has calculated how much it costs to service the uninsured in New York in particular, but a recent nationwide study showed that the country’s health care system would save between $65 billion and $135 billion if all of the patients it served were insured.

TWO SEPARATE SYSTEMS OF CARE

During the course of their education, students at Albert Einstein College of Medicine spend at least two Saturdays at the ECHO Free Clinic in the South Bronx. The clinic, which provides free health care once a week for those without health insurance, stays busy to the point of being overwhelmed, even though it shuns publicity.

“Word of mouth travels fast, especially when you’re talking about free health care,” said Rus Korets, one of the students who runs the clinic.

Students at Albert Einstein often work at private hospitals during the week, and many are struck by how frequently the medical strategies they have learned in school do not apply.

“I remember the first time I recommended giving an expensive drug, because … in medical school we learn the latest thing,” said Sharmilee Bansal, the clinic’s other student coordinator. “The [supervising physician] just looked at me and said, â€Do you know how much that costs?’ You learn there are other options.”

The existence of two sets of options based on insurance status amounts to "medical apartheid," according to a recent report (in .pdf format) by advocacy group Bronx Health REACH. In some hospitals, more than 95 percent of patients have private insurance; in others, 90 percent of patients are either uninsured or part of a public insurance plan.

Of the ten hospitals that see the largest proportion of publicly insured or uninsured patients, nine are city-run. In privately-run hospitals, those with private insurance have access to clinics that those without it do not have, according to the report.

Since 30 percent of African Americans and Latinos in the city don’t have health insurance, as compared to 17 percent of whites, the issue of health coverage cannot be separated from the issue of race, claims Neil Calman, one of the authors of the report. Lack of insurance, he says, is the number one reason that people of color are more likely to lose limbs due to diabetes, less likely to be tested for cancer following abnormal mammograms, and more commonly don’t live long enough to collect social security.

“While there are no longer signs that say â€Coloreds’ and â€Whites’ hanging over the doors of our institutions, nearly the same thing occurs when we discriminate based on insurance,” the report states.

While a systematic shift is the only way to change this, said Calman, there are immediate steps that could be taken at the state level. One is to change the way clinics are reimbursed by Medicaid from the current system, which pays clinics relatively little to treat patients with public insurance; the other is to make sure that hospitals receiving public funding to treat poor patients prove that this money is going directly to those who cannot pay for their own care.

PUBLIC HEALTH PLANS

Between 2000 and 2004, New York State reduced the proportion of its population without health insurance by about two percent, at a time when the percentage of Americans as a whole without health insurance rose about 1.5 percent (although, as recently reported in the New York Times, the percentage of children without health insurance is dropping across the country.) In doing so, New York State dropped below the national average of uninsured residents for the first time in over a decade.

These gains were secured entirely by expanding public health programs. Today, New Yorkers are more likely to be enrolled in public health plans than people elsewhere in the country. About 2.2 million city residents are covered by public plans, one million of whom, the city claims, were enrolled in the last year. This is about 80 percent of those who are eligible. (Of course, while officials cite this as a sign of success, it means that 20 percent of those eligible, or over 500,000 city residents, are not enrolled.)

New York State

Over the past several years, New York State increased the number of people who were eligible for programs like Family Health Plus, and Child Health Plus. It also tapped into private groups like community organizations and Health Maintenance Organizations to enroll people in public health insurance.

The federal government prohibits private groups from enrolling people in public health insurance, seeing a possible conflict of interest. But it has waived this restriction for New York State, making it the only place in the country where so-called facilitated enrollment exists. Health advocates estimate that half of all New York City residents who enroll in public plans do so through private groups.

“We love that people can go into the clinic where they’re getting care and sign up for Medicaid,” said Denise Soffel of the Community Service Society.

Funding public health insurance is expensive for all levels of government. The federal government, New York State, and New York City have all shown reluctance at times to support programs that increase the Medicaid rolls. New York’s legal ability to run its facilitated enrollment expires this spring, and late last month the state applied for an extension. But many worry that the federal government will not be inclined to grant it, and that Governor George Pataki isn’t willing to push for it.

New York City

The systematic planning for public health plans takes place in Albany and Washington. But Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently laid out a plan to encourage enrollment. His main goal over the next four years is to enroll all 214,000 children who are eligible for public insurance but not currently covered. He plans to do this by simplifying the application process. Eventually, he hopes, children’s coverage will be automatically renewed.

It is too early, say health advocates, to assess Bloomberg’s plan; its potential success depends on execution. But several expressed some concern that the mayor did not mention a plan to increase enrollment among adults as well, who make up about 80 percent of the city’s uninsured.

In New York, the relationship of local government to public health insurance is different than elsewhere. Unlike most other states, local governments here have to pay a quarter of their own Medicaid costs. This pulls local governments both ways – wanting to provide health care on the one hand, and to cut costs on the other.

The answer, says Bloomberg, is to get more private employers to provide health insurance, which he believes will “offer working New Yorker more choices and save taxpayers money.”

NEW YORK CITY AND EMPLOYER SPONSORED HEALTH INSURANCE

New Yorkers are less likely than people elsewhere in the country to get insurance through work, and the percentage of New York State residents with private insurance actually dropped between 2000 and 2004 (though not as much as it did elsewhere in the country).

Even for large employers who have enough employees to negotiate favorable terms, providing health care is a financial burden. General Motors says it pays $1,500 for health care costs per car it manufactures – more than it pays for steel. It cites these costs as a major reason for recent layoffs.

|

|

|

Manny Lanza died after unsuccessfully seeking care at the St.Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital.

|

|

Small employers have less money to spend and less room to bargain. As a result, a third of New Yorkers who work for businesses with less than 25 employees do not have health insurance.

First Pentecostal is on better footing financially than it was two years ago, and it has begun paying for Ebenezer Martinez’s prescription and for trips to the doctor. The board of trustees has also offered to split the cost of health insurance with him, and has asked him to find an appropriate plan.

“In this case I’m blessed,” said Martinez. “But looking for the right plan is not easy. They are very expensive, especially in my case because I’m an individual.” The health coverage he looked at so far ranged from $350 to $500 a month.

Bloomberg hopes to ease the burden on businesses by expanding on existing programs that allow small businesses to band together to secure better rates on coverage. But many say that such programs cannot provide full coverage at affordable rates unless the city subsidizes them heavily.

Not all businesses that fail to provide health insurance can plead poverty, however. When St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital turned Manny Lanza away he was working 50 hours a week at a “part time” job at Wendy’s fast food restaurant.

In an attempt to address the problem, the City Council passed the Health Care Security Act, a bill that requires food retailers with more than 25 employees to spend a minimum amount of money on health care for its employees. This bill would not have helped Lanza, however, because it does not cover Wendy’s. Critics say that the bill is a bid to keep WalMart out of the city, rather than a real solution, and complain that it is unfair to a single industry. Supporters respond by saying that the bill is a test balloon, and want to expand it beyond just food retailers. In any case, the mayor vetoed the council's bill, the council overrode the veto, and it now seems destined to be challenged in the courts.

Health care advocates view the city’s plans to expand employer-based insurance as well intentioned but doubt they will have wide effects. Real systematic change, they agree, is out of the city’s hands.

“All of [these programs] are going to do little teeny things that are going to help certain, limited numbers of people. And they’re important,” said Calman. “But there has to be a total, national solution to the issue. All the rest of this stuff is going to be constantly working around the edges.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Health Insurance Coverage in New York (United Hospital Fund)

NYC Uninsured by Community District (Mayor’s Office of Health Insurance Access)

Medical Costs the Number of Cause of Personal Bankruptcy (Health Affairs)

Separate and Unequal: Medical Apartheid in New York City (Bronx Health REACH)

Â

Bird Flu

For all the attention to the bird flu, discussions of its potential dangers are, for the time being, hypothetical. The disease may never spread from birds to any large segments of the human population, or, if it spreads rapidly among humans, it could be in a form that is not fatal. Still, the less optimistic possibilities are already prompting worldwide worry –- and that includes in New York City.

Some of the scenarios being spun if there were ever a full-fledged avian flu outbreak in the city are not reassuring. As imagined recently by several public health experts such an outbreak could kill 300 people each day, leave Grand Central Station and other public spaces completely devoid of people, and require forced quarantine of infected neighborhoods.

“The city would look like a science fiction movie,” said Dr. Irving Redlener of Columbia University’s school of public health. “This would look like an armed camp basically.”

While extreme-sounding, Redlener’s vision of an avian flu pandemic -– a widespread outbreak of a disease whose victims currently consist mainly of birds in Asia -– is not much different from that of the federal government. The worst-case scenario laid out in a plan of action from the Department of Health and Human Services includes riots at vaccination clinics, shortages of food and power, and $450 billion in costs. It predicted as many as 1.9 million American deaths.

New York City is also developing strategies to deal with pandemic avian flu, and believes it is better prepared than most cities to handle an outbreak. Still, a lack of faith in the federal government and unanswered questions about the nature of the disease itself continue to concern local officials.

FEARS CAUSED BY A NEW STRAIN

A disastrous pandemic flu outbreak is not without precedent. There have been three such outbreaks in the last 100 years, the most serious of which, the Spanish Flu of 1918, killed 500,000 Americans and 40 million people worldwide

The current cause of concern is a strain of avian flu called H5N1 that emerged in 1997. The strain is most prevalent in Asia, where the disease is responsible for the deaths of 100 million birds and about 60 people -- the only human cases to date.

The avian flu is more deadly than most flu strains, killing about half the humans it infects. But it is not easily spread. In its current form, the only way to contract avian flu is through contact with the feces or bodily fluids of infected birds; properly cooked meat cannot carry the flu. What worries health experts is the possibility that the flu could mutate so that it could be spread between humans, which might lead to a pandemic on a global scale.

Again, this may never happen. But the possibility is already prompting worldwide action. China has said that it will vaccinate each of its 5.2 billion chickens, one by one; international organizations and governments are developing plans to encourage drug development and identify outbreaks early; and the United States is spending $250 million to help contain outbreaks in other countries before they spread, while also tightening surveillance at its ports.

NEW YORK CITY’S PLAN FOR AVIAN FLU

The city’s Department of Health has been working on its response to avian flu for over a year, improving its disease detection system, running planning exercises involving hospital and other health workers who would be involved in coordinating any pandemic response, and offering free flu shots to see how well it can operate clinics deluged by large numbers of people. It will publish a full plan in early 2006.

As they contemplate their response to avian flu, city officials begin by acknowledging what they cannot do.

City officials will not be able to keep avian flu from entering New York City, said Isaac Weisfuse, deputy commissioner of the Department of Health. “Once it arrives, we can only try to slow its transmission,” he said. “We will not be able to halt it.”

Still, since 9/11, when the city turned its attention to the threat of a bio-terror attack, New York has been building its capability to deal with a major public health emergency.

“Although there is unquestionably a great deal to be done to prepare, the New York region is fortunate to have many aspects of the required preparedness infrastructure already in place,” said Susan Waltman of the Greater New York Hospital Association.

The first thing the city has done is to bolster its ability to identify disturbing disease patterns by improving the system it uses to track diseases like the regular flu. In doing so, the city is attempting to strengthen its relationships with the network of hospitals, clinics, and other health care providers that would also be involved in any response to an outbreak.

Such coordination would be essential, since health experts agree that the city’s hospital system would be overwhelmed by a full-blown pandemic flu. These concerns seem to run counter to the discussion about hospitals taking place on the state level, in which many argue that overcapacity is hurting the finances of New York’s health care institutions.

City Hall is already ruling out some of the more extreme measures that have been floated. City officials have rejected mass quarantine and the widespread use of masks, saying that neither would be effective if an outbreak did occur. Nor is New York City stockpiling drugs, focusing instead on refining the way it will distribute drugs if needed.

In fact, no vaccine for avian flu currently exists, and it is not clear whether Tamiflu, the antiviral drug used to ease symptoms of the regular flu, would have any effect on the disease. For the moment, the city is leaving it to other levels of government and the private sector to develop useable drugs and make them available if needed.

But city officials are also wary of leaving too much in the hands of the federal government, particularly after its performance handling Hurricane Katrina. This feeling of distrust was compounded at a recent city council hearing on avian flu to which both state and federal officials were invited to testify. Neither Albany nor Washington sent a representative.

“We would like to think, and it probably makes us sleep easier at night, that big problems like avian flu outbreaks or epidemics will be taken care of by the federal government. I don't know if it ever was [the reality], and it certainly no longer is,” said Christine Quinn, head of the council’s health committee. “Rightly or wrongly, the burden is going to fall on the cities.”

THE FEDERAL RESPONSE

The federal government does have a $7.1 billion plan to confront avian flu, which deals largely with developing and stockpiling drugs.

The federal plan also calls for state and local governments to develop their own emergency responses to a future pandemic. It provides $644 million to ensure that all levels of government are prepared for an outbreak, and is asking that state governments chip in on the cost of buying drugs in addition to coordinating treatment for patients.

Critics say that the federal government's plan doesn't provide state and local governments with adequate funding to carry out the tasks it has assigned them. "The plan sets lofty goals but largely passes the buck on practical problems," wrote the New York Times in an editorial last week. Weisfuse, of the city's Department of Health, told the city council that "the federal allocation was peanuts for state and local health departments."

FOR MORE INFORMATION

New York City Department of Health Avian Flu Fact Sheet

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Avian Flu Pandemics Fact Sheet

Pandemicflu.gov

White House Fact Sheet on its Pandemic Flu Plan

Department of Health and Human Services Pandemic Flu Plan

Â

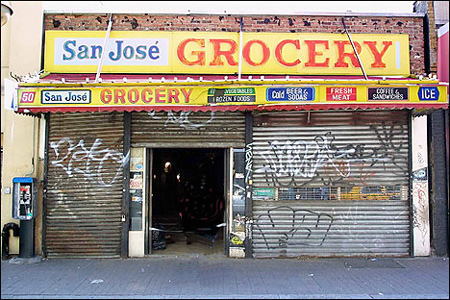

New York's Grocery Gap

The South Bronx feeds the region. Eighty percent of the metropolitan area’s fresh produce and 40 percent of its fresh meat comes through the huge Hunts Point market there. And with the opening of the new Fulton Fish market at Hunts Points last week, the neighborhood will be a leading supplier of fish as well.

| Related Stories in the Community Gazettes: • Growing Food in East New York • Marketing Health in the South Bronx • Small Grocers Survive on the Upper West Side |

But little of that fresh food reaches people in the immediate vicinity. Hunts Point is a wholesale market, off limits to individual consumers. The neighborhood has only one grocery store of any size – making it among the most poorly served communities in the city -- and less than a quarter of its bodegas carry fresh vegetables. (See related story.)

The South Bronx presents perhaps the most glaring example of New York’s food paradox: While the city offers an amazing cornucopia of food – gourmet treats, heirloom produce, food prepared to every religious specification and ethnic taste – some poor neighborhoods lack even a simple medium-sized grocery store. This forces residents to contend with high prices and the unhealthy food. That, in turn, contributes to soaring rates of diabetes and obesity.

FOOD CITY

Food is a multibillion-dollar business in New York City with more than 1,100 grocery stores of at least 4,000 square feet. New York boasts the fresh fish markets and vegetable stands of Chinatown, the Middle Eastern grocers of Atlantic Avenue and icons like Zabar’s. Markets such as Dean and De Luca and Citarella cater to the food obsessed planning to serve Belon oysters, foie gras and truffles on their Thanksgiving tables.

Despite all of that and tens of thousands of smaller delis, greenmarkets and bodegas, many New Yorkers confront what the American Institute of Nutrition has called “food insecurity” – an inability, either because of money or availability, to get safe, nutritional food.“Where to Grab a Bite,” (in .pdf format) a 2004 survey by City Limits, looked at the number of grocery stores in each ZIP code. If it's not surprising that affluent Soho has the most places to buy food per resident, it is certainly startling to discover that several ZIP codes in Queens, including ones covering parts of College Point and Bayside, have no grocery stores at all. Overall, Manhattan has the most grocery stores per resident; Brooklyn the least.

Despite all of that and tens of thousands of smaller delis, greenmarkets and bodegas, many New Yorkers confront what the American Institute of Nutrition has called “food insecurity” – an inability, either because of money or availability, to get safe, nutritional food.“Where to Grab a Bite,” (in .pdf format) a 2004 survey by City Limits, looked at the number of grocery stores in each ZIP code. If it's not surprising that affluent Soho has the most places to buy food per resident, it is certainly startling to discover that several ZIP codes in Queens, including ones covering parts of College Point and Bayside, have no grocery stores at all. Overall, Manhattan has the most grocery stores per resident; Brooklyn the least.

“It’s tough to get high quality supermarkets into the â€hood,” Alicia Glenn, vice president of Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group, has said. Supermarkets must sell a large volume of goods and so need large amounts of space – perhaps a half a city block.

And some in the food industry predict the grocery shortage could spread to more affluent areas as New York becomes an ever more expensive place to do business. “The better the neighborhood, the less supermarkets there are going to be” because rents are too high, said Morton Sloan, part owner of 10 Associated supermarkets in Manhattan and the Bronx.

Overall, said John Catsimatidis, the owner of Gristedes, the picture is “bleak” for grocery stores throughout the city, largely because of high rents. No one – from Whole Foods to the small mom and pop – is immune to the industry woes, he said, adding, “Something’s got to give.”

LIFE WITHOUT GROCERIES

“When I moved back to Central Brooklyn in 1985, I was struck by its barren nutritional landscape …. The storefront food provision systems themselves – â€bullet-proof’ fast food joints, poorly stocked and over-crowded supermarkets, cruddy, stomach-curdling bodegas – seemed to represent a level of self-destruction and dietary corruption that went well beyond my inability to buy tofu,” writes Mark Winston-Griffith. “Seldom do we consider one of the most basic elements – how an area feeds itself – as a sign of neighborhood well being.”

And many areas feed themselves expensively and unhealthily. In one study (in .pdf format) researchers found that a mango cost 67 cents at Pathmark, 79 cents at Associated -- and $1.79 at an East Harlem bodega.

The high prices are a real obstacle for many poor New Yorkers. Some 2 million people in the city are at risk of going hungry. As many as one in five –- and a quarter of the city’s children –- need help from food pantries and kitchens. This is double the national rate, according to a report by Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum.

But at least the East Harlem bodega had a mango. Many similar stores carry little fresh produce and no fresh meat or fish. In 2004, researchers compared the availability of several foods healthy for diabetics in East Harlem and Upper East Side grocery stores. Only 18 percent of the East Harlem stores had all five of the recommended foods, compared with 58 percent of the Upper East Side stores. And in East Harlem, stores selling unhealthy foods near schools outnumbered those selling healthy foods by almost six to one, according to one study.

HEALTH EFFECTS

All of this takes a toll on health. According to a 2003 study by the city health department, about 8 percent of all adult New Yorkers have been diagnosed with diabetes. With about a third of all diabetics unaware that they have the disease, as many as 12 percent of New York City adults could have diabetes – well about the national rate of 7 percent nationally.

In addition, an increasing number of New York City children are developing what used to be called adult-onset diabetes but is now referred to as Type II diabetes – because so many children now develop it. Doctors blame obesity, poor foods and lack of exercise. “Simple sugars, refined sweets, corn syrups, sodas, vegetables like potatoes and corn, without question, create an unfavorable environment for the pancreas," Dr. Henry Anhalt, director of pediatric endocrinology at Maimonides Medical Center, told the Daily News. He added that meals high in fat and calories, such as a typical fast food lunch, increase the risk.

Almost a quarter of all New York City elementary school students are obese, compared with a national rate of 15 percent. The problem is particularly severe among Hispanic children, more than 30 percent of who are obese.

ATTRACTING SUPERMARKETS

The problem has its roots in the 1950s and 1960s, when many grocery stores followed their middle-class customers to the suburbs. As a result, many who remained in the city had to rely “on small independent groceries that charged high prices and offered minimal variety and corner stores selling a limited selection of processed foods,” according to “Healthy Food, Healthy Communities,” a report by PolicyLink.

Although new stores have entered the city, the problem persists, despite tens of thousands of consumers eager for better food. “It’s not that they don’t want healthy foods or know the value of health foods,” said Kimberly Moreland of Mount Sinai Medical School.

In fact, many people go to great lengths to travel to good grocery stories. “People find a way to get to the supermarket,” said Rebecca Flournoy, a senior associate at Policy Link. “But if you’re going to have to take public transit and you’re on the bus for an hour and a half, and you have two kids with you and six bags of groceries, you’re not going to do it that often.” That makes buying perishable items particularly difficult.

Faced with this shortage, community and health activists, sometimes working with farmers or grocers, have tried to bring healthy food into communities. In some cases, the solution is a supermarket. For example, the Abyssinian Development Corporation and the Retail Initiative joined with Pathmark for a store in Harlem. The project stalled – due largely to opposition from small local grocers – but eventually opened in 1999. Such stores provide many benefits to the community, said Flournoy, including jobs and spurring economic development.

And the stores make money. “We’re pleased with the performance of our urban stores,” Harvey Gutman of Pathmark told Supermarket News. “The fact that we continue to open stores is evidence that we consider them to be successful.”

But, he said opening such stores in the city poses special challenges. “Land is scarce and expensive. Often it needs to be rezoned,” he said. “Opening a store in an urban community involves the participation and involvement of many political and economic entities.”

Rent provides a major barrier. To address that, some have proposed tax breaks for grocers, particularly smaller ones. (See related story.) Sloan of Associated would like the city to provide rent subsidies as well.

PROVIDING HEALTHY FOOD

|

But not every block can support a supermarket or even a medium sized grocery store. And so activists are looking to other ways to improve neighborhood food offerings.

In the Bronx, one effort aims to encourage bodega owners to provide healthier food. And farmers markets and farm stands have become increasingly prominent in the city. The leading effort is the 54 markets run by the Greenmarket project of the Council for the Environment of New York. These greenmarkets feature farmers from upstate, Long Island and New Jersey who come into the city once a week or more to sell produce and farm related products, such as jam and bread. Just Food, a non-profit organization, has sponsored 33 community supported agriculture – or CSAs – in the city. In these buying clubs, residents of an area agree to purchase food on a regular basis from a small farmer. The customers get a guaranteed source of fresh food; farmers get a guaranteed source of income.

Just Food also runs the City Farms project, which works with gardens in the city to distribute what they grow to the community. In 2004, some gardens in the city produced more than 30,000 pounds of food.

Some gardeners sell their wares in farm markets, such as East New York Farms! (see related story) and at so-called urban farm stands. The gardens also donate to soup kitchens and food pantries. “Community gardeners know who needs the food,” said Rebecca Ferguson of Green Guerillas.

The city’s economic health can hamper such efforts. In more depressed cities, says Kathleen McTigue of Just Food, it’s easier to find land to cultivate. Here, she said, “you have to make the most out of small growing spaces.”

But, said Ferguson, the potential in New York remains “massively untapped.” Land awaiting development can be farmed she said, and vegetables can be grown on rooftops and in window boxes.

Some of the available land is returning to an old use. For eight generations, beginning in the 1650s, Wyckoffs lived and farmed in East Flatbush, helping to make Brooklyn and Queens centers of agriculture as late as the 1880s. While Brooklyn will probably never return to its agricultural heyday, area residents are once again farming the grounds of the Pieter Claesen Wyckoff House. And on Sundays in the summer and fall, a farm stand – the kind of thing one expects to see on a back road upstate – sells home grown goods, in the middle of the drab urban landscape – and in front of Brooklyn’s oldest house.

For More Information:

Food Bank for New York City

Green Guerillas

Greenmarket, Council on the Environment of NYC

Hunger Action New York State

Just Food

Northeast Regional Anti-Hunger Network

Articles and Studies

“Where to Grab a Bite,” (in .pdf format)

Food Redlining: A Hidden Cause of Hunger

Harvest in the City (Earth Island Journal)

Healthy Foods, Healthy Communities

The Hoax of the Food Desert (Ludwig von Mises Institute)

Hunger and Obesity in East Harlem (in .pdf format) New York City Coalition Against Hunger

It’s Just Food (NYU School of Journalism)

Splat (New York) The war between Fresh Direct, Fairway and Whole Food

Â