City Council Stated Meeting - November 16, 2005

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. Gotham Gazette covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

QUOTE OF THE DAY:

"The unions saved this city in the 1970s, they were part of the inception of campaign finance in the 1980s, and they should be given a fair and equal opportunity to have full participation [in the political process.]" - Councilmember Leroy Comrie on easing campaign finance restrictions for union donations.

MEETING SUMMARY:

CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS FROM UNIONS

New York City's Campaign Finance system, which offers candidates matching funds in return for agreeing to spending limits, has been hailed as a model for the rest of the nation. It is also a system that has benefited all 51 City Council members, who receive $4 for every $1 they raise in small donations.

On November 16, the City Council voted to amend the Campaign Finance law as it relates to donations from labor unions. The council says it is protecting city workers' interests; critics say it is giving too much power to organized labor.

Earlier this year, the Campaign Finance Board voted to prevent unions, who can give up to $2,750, from using their local affiliates to funnel additional money to candidates. Under the decision, a union like the Service Employees International Union could only give one donation to a candidate even though it is comprised of local groups like Local 32B and 32J, which represents maintenance workers, and 1199, which represents health care workers.

The council argues that the Campaign Finance Board went too far and is being unfair to workers, who have distinct needs and may want to support different candidates. For example, in the recent election, Local 32B-32J supported Mayor Michael Bloomberg, while 1199 supported Fernando Ferrer.

Under the council's bill (Intro 564-A), a candidate can accept multiple donations from a union and its affiliates as long as:

- the donations come from different bank accounts

- the unions maintain different signatories

- they have distinct governing boards

- and they do not share a majority of officers.

"This is an important effort to protect the rights of free speech of working men and women and protecting their ability to participate in the political process," said Councilmember Bill deBlasio, who authored the bill.

"The unions saved this city in the 1970s, they were part of the inception of campaign finance in the 1980s," said Councilmember Leroy Comrie, "and they should be given a fair and equal opportunity to have full participation."

But critics say that the council has created a loophole that gives labor unions too much influence. Newspaper editorials have called the legislation a "City Council Money Grab" and "a suck up to [labor] bosses."

The measure passed easily by a vote of 43 to 3; only Madeline Provenzano, Eva Moskowitz, and Andrew Lanza voted against it.

Councilmember Peter Vallone, Jr. abstained, calling it a "flawed bill."

Mayor Michael Bloomberg said he will veto the measure; the council has more than the 34 votes needed to override the veto.

PROPERTY TAX RATE

In an effort to shift the city's property tax burden from homeowners to commercial property owners, the council approved a change in the tax rates.

Although the citywide property tax has remained the same since Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council increased it by 18.5 percent in 2002, the state adjusts rates annually to keep pace with the real estate market.

The council's action lowers the state's proposed 7 percent tax increase for single family homes to 4.3 percent , which will save the average homeowner $80. It also increases taxes for Class A office buildings; the average building in Manhattan will see a $168,000 hike.

While most council members applauded the move, others complained that homeowners will still see an increase when their next bill arrives.

"While we can all be pleased that we are doing the right thing... the next tax bill they get will be more than the last," said Councilmember Lew Fidler. "I guarantee you at the end of December, my office and all of yours will be besieged with phone calls saying, 'How come you raised our property tax bill again.'"

The three Republican members - James Oddo, Andrew Lanza, and Dennis Gallagher - voted against the adjustment, arguing that property taxes should be reduced.

The council's action does not affect the $400 property tax rebate for homeowners, which the mayor has promised to continue next year.

PROTECTING RELIGIOUS PROPERTIES

In 2004, there were 350 documented Anti-Semitic incidents in New York City, according to the Anti-Defamation League. In response, the council passed a bill (Intro 703-A) increasing fines from $10,000 to $25,000 for vandalizing religious properties.

"I am not sure it will be a deterrent for a knucklehead who is so full of hate and stupidity that he desecrates a house of worship," said James Oddo. "It is intended to be a 'financial life sentence' of sorts."

SPORTS STADIUM CONDUCT

In 2003, the City Council passed a law making trespassing on professional sports playing areas a misdemeanor and increasing fines and penalties for those who violate the law.

The council strengthened its "sports stadium security policy" with a bill (Intro 528-A) that adds spitting, throwing objects, or physically hitting someone on the field to the regulations.

"Our families should not be intimidated by drunken idiots in any stadium," said Councilmember Peter Vallone, Jr.

RECYCLING BATTERIES

The council also approved new recycling programs (Intro 70-A) for rechargeable batteries.

"Rechargeable batteries have many toxic substances and people throw them away by the millions," said Councilmember Oliver Koppell. "They get into the waste stream, and they poison our land and our water."

Manufacturers and marketers of products that use rechargeable batteries will fund the project. Approximately 37,000 retail stores throughout the city and on the Internet, such as Radio Shack, Home Depot and Verizon Wireless will collect the batteries and send them to manufacturers. There is no cost to the city.

Only one member, Simcha Felder, voted against the measure.

PLUMBING CODE

The council approved a new 400-page plumbing code (Intro 478-A). It is the first part of an entire overhaul of the city's building code that the council's housing and building committee has been working on for much of the last four years.

DUMBO BUSINESS IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT

The council also voted to create a business improvement district (Intro 691) in the Brooklyn neighborhood DUMBO. Business improvement districts provide activities or amenities that promote business in a specific area, including maintenance and sanitation, holiday decorations and other efforts. They are funded by assessments on property owners within the area and overseen by the city's Department of Small Business Services.

All bills (except for the campaign finance, property tax adjustment, and the battery recycling program) passed unanimously by a vote of 48 to 0. Maria Baez, Phil Reed, and Larry Seabrook were absent.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for November 30, 2005.

Â

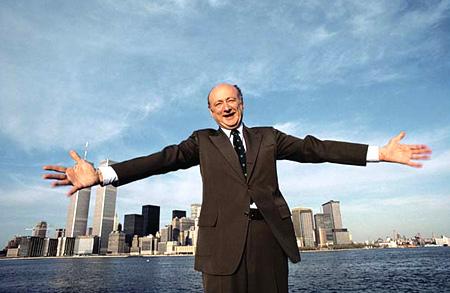

Ed Koch's Legacy

Michael Bloomberg has demonstrated that a mayor can “competently manage the city without building a personality cult at City Hall,” a commentator wrote recently. No one would say that about Ed Koch. “Mayor Koch was so in your face for so long that a whole generation of children grew up thinking â€Mayor’ was his first name,” said former Daily News editor Michael Goodwin.

Recently – 28 years after Koch won the mayoralty – a panel revisited the Koch years. They recalled a mayoralty that revived a city scarred by fiscal crisis, crime and decay. They paid less attention to Koch’s defeat in 1989, when voters, tired of the “shtick” and disgusted by corruption and racial tensions, ended Koch’s time in office.

The following discussion, moderated by Goodwin, featured journalist and novelist Pete Hamill; Stephen Berger, former director of the Emergency Financial Control Board; New York Times columnist Joyce Purnick; the Reverend Al Sharpton; and Victor Gotbaum, former executive director of the municipal workers union, District Council 37. The forum launched “New York City Comes Back: Ed Koch and the City,” an exhibition currently on display at the Museum of the City of New York.

This is an edited transcript of the discussion.

Intro - "The Good Fight and the Good Quip"

Pete Hamill - "Our Pain in the Ass"

Stephen Berger - "He Would Balance the Books"

Al Sharpton - "He Launched My Career"

Ken Auletta - "Entertaining Conflict"

Joyce Purnick - "The Unstoppable Ego"

Victor Gotbaum - "His Enemies Created Him"

Ranking Koch Among Mayors

Corruption and Scandal

What Koch Did Not Do

THE GOOD FIGHT AND THE GOOD QUIP

Michael Goodwin: In January it will be 28 years since Edward I. Koch first took the oath as the 105th mayor of the city of New York and 16 years since voters made him a private citizen. The 12 years in between were like no other in the recent history of the city. The Koch years were unique -- all the energy and change and drama. The fate of the city was at stake. It wasn’t just the finances sinking. It was the civic spirit that was sagging too. Once a great metropolis, New York had fallen and it couldn’t get up.

But it did get up -- because Ed Koch pulled it up. In a 1984 interview, the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan said, “Ed Koch has given New York City back its morale…And that is a massive achievement.”

Indeed it was. The ride was not always smooth. How could it be with Ed Koch at the helm?

One thing was always certain. We knew who was boss. Mayor Koch was so in your face for so long that a whole generation of children grew up thinking “Mayor” was his first name. He relished the good fight and the good quip. Here are a few of his favorites:

“The UN is a monument to hypocrisy.”

“I don’t get ulcers; I give them.”

When he refused to pet a tiger at Madison Square Garden, a bystander yelled, ”Mr. Mayor, a coward?” To which the mayor responded, “No, the mayor is not a coward. And the mayor is not a schmuck.”

Then there are those comments he made to Playboy magazine just as he was starting the 1982 campaign for governor. Koch called them “the dumbest he ever made.” There’s no argument here, considering some of what he said: “Living in rural areas is a joke.” “Have you ever lived in the suburbs? It’s sterile. It’s numb. It’s wasting your life” And he talked about wasting time in a pickup truck when you have to drive 20 miles to buy a gingham dress or a Sears Roebuck suit. To top it off, he said, “Living in Albany would be a fate worse than death.”

On Election Day, he was spared that fate.

The time is right for a second look at those years.

CONFRONTING DESPAIR

Pete Hamill: When Ed Koch took office on the first of January 1978 there were neither parades, rallies, preparations for bonfires nor any sense of celebration. The fact was that we had gone through such a terrible time there was no reason to celebrate.

It’s hard to imagine now what faced Ed Koch when he walked into City Hall. In the fall of ’75, the fiscal crisis erupted. There were layoffs: cops, firemen, sanitationmen, teachers, librarians. At the same time, there was a kind of nexus – a gathering together – of three factors: youth, drugs and guns bringing a sense of menace to our city that simply wasn’t there before.

Crime was growing. But the dailiness of our lives was even worse. Bags of garbage opening in the streets. The South Bronx and Brownsville were burning. The homeless suddenly appeared among us. They were not black or white or Latino. They were everyone. Some of them had been displaced by the burning of the South Bronx and had lost their places to live. Some of them were drug addicts, some of them were alcoholics, some of them were lost souls who have been in this city since the time of the Dutch. The shopping bag lady became a symbol of New York. Not a criminal, but just another lost soul wandering around with all her possessions.

At the same time, a guy named David Berkowitz, better known as the Son of Sam, was roaming the streets. His miniature psychopathic crime wave started in July of ’76 and didn’t end until August of ’77.

And along came Koch. At the beginning, no one gave him a chance. He was the classic Greenwich Village liberal. He had gone to the South to march for civil rights. He opposed the war in Vietnam. He was the object of all the stereotyping that goes along with a place like the Village. And he started running. Nobody paid much attention. Later, a new player in town named Rupert Murdoch decided that Ed Koch was his man and gave him a little more ink than he was getting anywhere else.

Then on July 13, we had a power failure. Twenty-five hours. Fires broke out, there was looting of some of the worst junk in the Western hemisphere. Paintings on velvet. The worst looking television sets available anywhere in the United States. Crappy little toys. The police, undermanned as they were, made 3,776 arrests.

The sense of despair among many New Yorkers was genuine. A lot of my friends said, “I’m leaving." Some of them committed a form of suicide and moved to New Jersey. Others went to Florida and, God help us all, California. It wasn’t simply a matter of us losing their tax money. We lost the thing that they were – New Yorkers.

Along came Koch. And in the first month, we suddenly started paying attention in a way we had not during the election. Here was a mayor who was a combination of a Lindy’s waiter, a Coney Island barker, a Catskill comedian, an irritated school principal and an eccentric uncle.

He talked tough and the reason was, he was tough. He was in combat during World War II as an infantryman. He was awarded two battle stars and came home a sergeant in 1946. He didn’t profit from the war like so many. He fought it.

That toughness was key to what I began to think of -- and I’m sure everyone else did -- as “the act.” He also was very wise and intelligent about the way he approached his job. He knew he couldn’t govern in the traditional sense because of the fiscal crisis. The power had fallen to Hugh Carey, Felix Rohatyn, the Municipal Assistance Corporation board, faceless bankers. But while Koch couldn’t govern traditionally, he could entertain us. In a way, that was better.

He came at us with a sort of scorn for weakness and self-pity. All sins were permissible in New York except self-pity. Admittedly, he could be ugly in conversations. But most of the time he made you laugh out loud. And it worked. It worked because he knew the problem in New York was not crime. It was morale.

And he went at it with a sense of joy, a sense of combat, a sense that made us all know “that’s the voice of New York, that’s what we are.”

There was something touching about him too. When the lights went out and the rallies were over, there was a sense of loneliness in Koch -– something that made him more human. Then you think about what happened in the third term when so many people he trusted betrayed him, and his sense of isolation grew. He should not have had to go through that.

The press failed him too. We were covering candidates and not paying attention to all those little offices where Bartleby the Scrivener sat in the corner.

I always think of him now with an enormous affection. He was a huge pain in the ass, but he was our pain in the ass, and we’re lucky to have had him.

THE FINANCIAL MESS

Stephen Berger: Once upon a time, the state legislature was controlled by upstaters and the city had wealth. We were actually exporting revenue into the state.

We also had continuing waves of immigration. So we had very strong social programs in the state. If you look back, you see that a historic deal was openly cut. We live with it today. You see it with Medicaid and welfare programs. It’s basically a deal that said, that unlike any other state in the United States, in New York the local government –- in this case New York City -– would pay half of the state’s cost of many of these social programs.

The second piece is that Albany was not just 150 miles away from New York City. What we learned during the fiscal crisis was that neither the city nor the state really understood that they were two black boxes held together with a piece of string. They didn’t understand how we worked, we didn’t understand how the state government worked and there was a total breakdown in communication between the state and the city.

Third, New York City’s commitment to social programs came with an arrogance and a self-righteousness, which overlooked the range and scope of programs, that a state with full taxing power would have had trouble maintaining.

There were many warnings of the fiscal crisis. New York City raised taxes 15 times [during the 1960s and 1970s]. We were constantly outspending our budget. The city spent all its reserves. The city raided its capital budget, robbing its future to pay for its present

From the mid 1960s to the early 1970s, there were public commissions, city commissions warning of the coming crisis. It would take every dollar of personal income inside New York City to find that money. By 1975 –- this was how broke the city was in 1975 -- it had effectively borrowed every dollar it was going to raise in local revenue for the next year. You start January 1, and you’ve already spent more than you’re going to take in the next year. Now that’s exactly where we were. It was $7 billion. Even in today’s terms, $7 billion is a fair amount of money.

Finally, the lenders said, “we’ve had enough.”

From 1976 to 1977, the [financial] control process was put in place. It stabilized the situation and created a new financing structure.

But for the city to restore itself and return to self-government, it had to show it could run itself efficiently and effectively, balance its budget, year in and year out. The revenues had to match the expenditures. The city had to keep it balanced and then persuade the lenders.

No one was better prepared to take over than Ed Koch. In part that was because he was an observer at the Financial Control Board. He was not an outsider. He had an understanding of the problems. So, he knew why he had to balance the budget. He had to manage the city. He had to persuade the workforce to do more with less. He had to rein in spending for the poor. He had to persuade the lenders to believe in us again.

He brought the energy and the discipline that remain today and are the basis of the confidence that people have in the city. Unlike his predecessors, he would balance the books.

RACE RELATIONS – AND LAUNCHING AL SHARPTON

Al Sharpton: Part of the thing that was most refreshing and most appalling about Koch is that he will stand for what he believes in. He will not say what you want him to. And he will not be intimidated either way.

He always was a bit of a showman and was a good politician in terms of being able to convince people. He has my daughter convinced that the only reason he was the first to arrest me was to launch my career.

It was on April 4, 1978, which was the anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King... We arranged a meeting with the mayor. The fact that he would even see four unknown ministers showed that he was more open than we gave him credit for.

We wanted to demand that the federal government replace the cuts in summer jobs for youth that summer. And Ed Koch, unlike many liberals at the time, looked at me and said, “No, and I’ll tell you why.” And I said, “What do you mean no?” He says, “No. I’m not going to do that.” And I said, “Well if you don’t, we’re not going to leave your office.” And he said, “Let me explain to you why your approach is wrong.”

He had a job to manage the city and I think that, even if he felt our core reason was right, he felt he had to have an administration that would appear to not deal with [those who did not] stay within certain boundaries of the law. So, after he lectured us for an hour that the federal government had fiscal problems, the city had fiscal problems, that of course he wanted young people to be working and our approach was not the best approach to get him to do it, he asked the police to come in and remove us. I remember the young man who was standing in uniform with handcuffs. And he said, “Well, we need a complainant.” Koch says, “I am. Arrest them. I’ll sign the complaint.” And we were carted out on the stairs of City Hall. It was the first time I was arrested, and some 20 some years later at my birthday, he reminded me that no one had heard of Al Sharpton until then.

I invited him to my birthday. About 2,000 people were there -- mostly African Americans. He and I had been working together on the Second Chance program. I didn’t know how these Harlem people were going to respond. And he came on stage and everybody stood and started clapping. He walked to the microphone, and he looked at the crowd and said, “Do you miss me?” Well, after Giuliani we really did miss you.

At the end of the day, he had respect for African Americans and Latinos. He respects us enough not to placate us. We probably would have liked it better if he told us what we wanted to hear. But he respected us enough to talk to us like adults and tell us what he was and wasn’t going to do. And as I got older I learned to respect people more that didn’t give me empty promises just to get me out of their office. When he said yes, I could go and say he would keep that yes and when he said no he meant no. Even when I thought he was wrong, I never felt he was disingenuous.

Michael Goodwin: Could you elaborate more on racial tensions and his effect on race relations.

Al Sharpton: Well I think the tensions were national and that the mayor inherited a lot of things in the African-American and Latino community that were happening then.

His personality became an easy target because he was so in your face. I think it was not so much his stand on the issues as his style that caused confrontation at the time.

Race relations because of Howard Beach and Bensonhurst and other incidents became very, very bad. The legacy of those years was that we did get through. What no one talks about is that New York had no riots like South Central or Watts. One of the reasons I think is because we dealt with it openly, and we dealt with it squarely. The lasting situation in the city is that we talk about the issues. I don’t think we’re anywhere near racial harmony, but there is more racial sensitivity than there was.

Koch steered the ship through some very turbulent waters...

THE MAYOR AND THE MEDIA

Ken Auletta: When Koch ran for mayor in 1977, he believed that the city government and the city administration were much too compromised. He believed that special interests ran the city. And he spoke words sharply, and the press loved hearing that.

And he had this way, as Reverend Sharpton said, of standing up to people and not trying to placate them. That married very well with the press’ interest in conflict. And it also married very well with the mood in the city at that time.

Then what happened –- the secondary thing –- is that Rupert Murdoch stepped in and not only endorsed Ed Koch -– the New York Daily News endorsed Ed Koch, the Times endorsed Mario Cuomo -– but Murdoch not only turned his editorial pages over to Ed Koch, he turned his front page over to Ed Koch.

As a congressman, Koch did not fill a room. We knew he was smart. We knew he was outspoken. But when he ran for mayor, Ed Koch was transformed. He became what we call a personality. And I think he filled that room.

In 1978, he starts giving press conferences and so he met the second bias of the press: to be entertaining. He gave great sound bites. And the TV press played that up. He was very charming for a long period of time, just asking that question, “How am I doing?” But after a while, particularly with the media, it begins to wear thin.

And, as Pete said, it may have caused problems because we tended to focus on the personality of the mayor and to ignore the government. And in truth, there a second question he should have been asking which was, “Hi, how’s my government doing?”

By his third term, that second question became predominant. If you look back on his three terms, you see he performed in a way that no mayor had since La Guardia. As Pete eloquently said, he gave us back our morale, but he gave us back our self-government too.

THE RIGHTWARD SHIFT

Joyce Purnick: I know I’m getting old when I hear Reverend Al Sharpton speak in laudatory terms of Ed Koch.

I will try to summarize a half-century of Ed Koch’s political evolution in five minutes. He was a Greenwich Village liberal who moved to the center -– some say to the right –- as he saw more and experienced more of government. There is no doubt that Koch’s evolution was a reflection of what was going on in our society, particularly among many Jews. There was a souring of the traditional alliance between Jews and blacks partly because of the changes in the city during John Lindsay’s years, with middle class anger over Forest Hills and Ocean Hill-Brownsville (in PDF format).

I will try to summarize a half-century of Ed Koch’s political evolution in five minutes. He was a Greenwich Village liberal who moved to the center -– some say to the right –- as he saw more and experienced more of government. There is no doubt that Koch’s evolution was a reflection of what was going on in our society, particularly among many Jews. There was a souring of the traditional alliance between Jews and blacks partly because of the changes in the city during John Lindsay’s years, with middle class anger over Forest Hills and Ocean Hill-Brownsville (in PDF format).

I’m not convinced Koch was ever quite the classic Village/West Side liberal that some people thought he was. I don’t think his focus in his liberal youth was as much ideological as it was tactical.

In any event, by the time he ran for mayor he was taking on the teachers union. He won the primary in large part because he ran in the center -– to the right -- and in large part because of his temperament, his candor -- not his sense of humor because Ed Garth kept that under wraps in 1977.

I think that it’s fair to say that Ed Koch wasn’t as revolutionarily a centrist as he might have wanted to be. But there were the unions. There was the Board of Estimate to deal with, the state legislature to get legislation through. You can’t be fighting with everyone all the time.

The inclination was to govern more as Rudy Giuliani did eventually. Even Giuliani didn’t stray as far from the traditional as he would like us and the rest of the country to believe. If Koch wanted to govern that way, I don’t think he really could have. There were realities to deal with. And, as we all know, he couldn’t keep fighting the party leaders. Instead Koch made alliances with those leaders.

He said he did so to govern, to get legislation through Albany. And I’m sure that is part of it. But I think in part it was also his ego. By making those relationships, Koch signaled his acceptance of those leaders and the way they functioned. Inadvertently that led to corruption scandals of his third term.

Now not even Koch’s harshest critics have ever accused him of personal corruption. The problem was two-fold. The bad guys thought they could get away with it. The other problem was Koch’s naivetĂ©. What else could explain his kissing Donald Manes on the forehead after Manes' attempted suicide?

I remember when Koch turned against Manes and called him a crook. At the time, Ed Koch seemed shocked. I don’t think the pattern of corruption seemed possible to him. I don’t think he understood that doling out low-level patronage in City Hall’s basement could have led to corruption. I don’t think he realized it sent out a message to those intent on abusing the system.

I do not think that the corruption scandal will be anywhere near the center of Koch’s place in history. I think it will be overshadowed by two pieces of his legacy. One, as we have discussed, getting the city back on track after the fiscal crisis with the kind of spirit and energy that the city needed and which the entire world would know. The transit strike. The “how am I doing?” stuff. The unstoppable ego. He loved to talk to us about the city and we loved to listen.

Secondly, I think that Koch was a harbinger of a major change in the way we govern large cities. He began the change from the old coalition of labor, liberals, minorities and the clubhouse that has since taken us through Giuliani and to Bloomberg. It’s popular today to credit Giuliani with changing of the city’s politics as usual, but I think that began with Koch. He took it as far as he and his roots would let him. Giuliani broke the rules, Bloomberg ignores them, and Koch wrote his own rules with his personality and his spirit and with his love of politics.

LABOR RELATIONS

Victor Gotbaum: It’s really an oxymoron for me to be up here praising Ed Koch. He was tough. He didn’t discriminate when he took office –- he zinged everybody he thought didn’t fully do the job of helping New York City.

And I must say that, at the beginning, I didn’t dislike Ed Koch. I despised him.

A woman I know [Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum] – I happen to be married to her – said, “The reason you don’t like him is because you and he are so alike.” I didn’t talk to her for at least six minutes.

An interesting aspect of Koch is that his enemies made him. The 1980 transit strike. Any labor leader knows that you can’t win the hearts of the public if you go on strike. You may have to do it if workers are really repressed, but in the mainstream you take a terrible, terrible beating. It was the ’80 strike that really made Ed Koch. He took a strong stand. He walked across the bridge as you all recall. Labor might have hated him for it, but he knew exactly what he was doing.

[In another case,] he wanted 35 layoffs, and I opposed him. I knew that if I took him head on, it would be a bad mistake. So I negotiated with him on changing the titles where they would do work and get federal money. He listened and then I discovered something about him: He could negotiate and he would negotiate.

The only reason Koch and I get along at all is that Betsy liked him. She mentioned two things: that Ed Koch didn’t represent the city, he was a piece of the city. He was a part of the city. You couldn’t divorce Ed Koch from the city.

Another aspect of him – and I was trying to think of another word – but he was pure schmaltz. I mean that in a positive sense. He was so much a part of the city that he could get away with it. He would do things that other mayors couldn’t do.

It was his brashness, his moving forward, and his feeling, his strength that he was doing the right thing for this city. So you could negotiate with him, be angry at him, but he would never, never hurt the city that he loved so much.

RANKING KOCH

Michael Goodwin: Of all the New York City mayors of the 20th and 21st centuries, where would you rank Ed Koch?

Pete Hamill: Second or third after La Guardia. If you had to write a novel about a New York City mayor, you’d rather write about Koch than Robert Wagner, and Abe Beame would be like writing about a turnip or something. But I think the three would be La Guardia, Koch and Giuliani – the first term. Not the second term.

Stephen Berger: I would focus more on the first two terms where Ed was an architect and an engineer. He was a cheerleader. And he not only put stuff together but put them together in a way that it’s held up by and large now for 35 years. That’s got to put him right up there.

Joyce Purnick: That sounds right to me. Everyone puts La Guardia at the top. Bloomberg has accomplished a lot of what Giuliani claimed to have accomplished.

Ken Auletta: It depends upon whether you count Bob Moses as a mayor – then you have to assess whether his influence was good or bad. But I think Ed Koch is up there with La Guardia.

It reminds when I said to Hugh Carey, “You know you’re probably going to go down as probably the third best governor in this century.” And he said, “Really? Who are the other two?”

WHAT WENT WRONG?

Michael Goodwin: How would you describe Ed Koch’s greatest failures?

Michael Goodwin: How would you describe Ed Koch’s greatest failures?

Pete Hamill: He didn’t pay enough attention to Bob Dylan in "Subterranean Homesick Blues," particularly the line, “Don’t follow leaders, watch the parking meters.” In many ways it’s admirable that he did not see people as potential felons. But he trusted some people who betrayed his faith. That’s nothing to be ashamed of.

Stephen Berger: We never had a mayor who had more potential to do what should be done in the state. This is to take all the cities and all the counties –- all the local governments –- and lead them against a state bureaucracy, a state government, which is clueless about local government. He had the political skills and the political instinct to put that kind of coalition together. The problem is you have to go north of the city to do that. I think if Ed had done that he could have made a difference.

Every one of those guys throughout the state, whether you’re in Erie County or the mayor of Syracuse, has some of the same problems that the City of New York has. I think being in a real coalition with those guys could have made a real improvement.

Joyce Purnick: Hubris. If you take it down a few pegs you don’t have Ed Koch, so it’s double edged, but maybe half a peg.

Ken Auletta: If you go back to Greek mythology that virtue is also a vice, then if you review Ed Koch’s vices, narcissism, his preoccupation with himself and being on stage, you also remove some of his virtues. I think the good comes with the bad and the bad with the good.

Michael Goodwin: Victor, if you could change one thing, what would you change about Koch?

Victor Gotbaum: I wouldn’t let him get elected.

WHAT KOCH DID NOT DO

Audience member: There were failures in his administration in my opinion. He let the public schools deteriorate, Westway was never built, race relations did not improve, and for the buildings along the Cross Bronx Expressway that had been decimated, [his] solution was to put up decals.

Michael Goodwin: There were many problems that did not get solved. He tried to focus on some of them. Education obviously was a big one. Interestingly, I think we’re now looking at education as a key issue just as crime was a key issue in the previous eight years.

So you have a kind of changing of the guard of ideas that are considered prime topics. With Mayor Koch, obviously finances were the first problem. You have a limit to what you can achieve.

Stephen Berger: You have to be able to focus on a few things if you want to be successful. You cannot do 20 things and do them well. What works is what the mayor or chief executive decides is going to work.

“New York Comes Back: Ed Koch and the City” is on display at the Museum of the City of New York through March 26, 2006.

Â

Rising Heating Costs

This year New Yorkers will face sharp rises in home heating costs, and while there is some government assistance available to individuals of low income, it is likely that the great majority of those eligible will never receive it.

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita significantly damaged oil-refining capacity in the Gulf Coast, and oil prices climbed to more than $70 a barrel in late August. What this means for the average New Yorker who uses home heating oil, according to Senator Charles Schumer, is an increase of some $450 in heating costs over last year.

Many New Yorkers use natural gas to heat their homes, and the major hub for transporting natural gas to the Northeast is also located in the Gulf Coast region -- which is why the average New Yorker using natural gas will see a price rise that is even higher, at some $473.

Federal Efforts To Reduce Heating Costs

Northeastern senators of both parties have called upon the Department of Energy to release heating oil from the Northeast Heating Oil Reserve . President Bill Clinton established the reserve in 2000 in order “to reduce the risks presented by home heating oil shortages”. As of early November the department has refused this request, arguing that the situation is not serious enough to justify tapping into the reserve.

Another idea that has gained the support of Democrats as well as typically tax-averse Republicans, is to impose a "windfall tax" on oil companies . All of the major companies posted record profits in the third quarter of 2005, at the same time that many consumers faced record-high gasoline prices. Some proceeds from this tax would help poor and elderly Americans pay their heating bills.

The oil companies argue that their profits are not disproportionate, and that a windfall tax would reduce their incentive to locate new sources of energy. They have a powerful ally in President George W. Bush, who is opposed to the idea.

Individual Assistance With Heating Bills

Regardless of how the political skirmishes are resolved, the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) will help individuals pay their heating bills. This is the primary federal program for this purpose, and it took effect in New York State on November 1, 2005, though it is not yet clear how much money will be available. (For fiscal year 2005, New York State received $235.6 million in such funds.)

In New York City, these funds are administered by the city's Human Resources Administration. Individuals can receive assistance whether they pay their heating costs directly or if these costs are included in their rent. Eligibility is based on an individual or family’s monthly income, and the program provides both regular and emergency benefits of up to $400 a year. The city estimates that it provides almost 440,000 grants each year, for a total of about $31 million.

The National Fuel Funds Network, an umbrella group for 250 organizations nationwide (including in New York City, the HeartShare Neighborhood Heating Fund) that raise donations to help people with their heating costs, estimate that only 15 percent of individuals eligible for the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program actually receive assistance. Marcus Banks is a librarian at the New York University School of Medicine.Â